In March 2011, the publisher Continuum released Daphne Carr’s book Pretty Hate Machine as part of their 33 1/3 series of think pieces about significant albums. A good number of Nine Inch Nails fans bought Carr’s volume, hoping to learn more about what happened behind the scenes in writing and recording the 1989 debut, such as what equipment frontman Trent Reznor used, which records he sampled, how he got his contract with TVT, and the presumably juicy stories of the failed relationship(s) that inspired his angsty tunes. What these readers got, much to the outspoken online annoyance of many, was instead Carr’s meditations on Rustbelt Americana in the 1980s, depression and masculinity, white suburban pride, the Hot Topic mall store chain, and the 1999 shootings at Columbine High School. Huh? How dare she write a book about Pretty Hate Machine and not interview its A-Team lineup of producers John Fryer, Flood, Adrian Sherwood, and Keith LeBlanc? Or track down Reznor’s ex-bandmates and manager? However, what Carr succeeded in doing through her ethnography and interviews with Pretty Hate Machine’s enthusiasts was to suggest that beyond the album’s blipping synths, cut-up guitars, and hip-hop samples, there’s an important story waiting to be told about why modern suburbia so desperately needed an industrial music to call its own. It’s an elegant illustration of the previous chapter’s suggestion that an album’s public life after its release date can be every bit as important as the private gestation that preceded it.

Because this is a critical history of industrial music, let’s consider Nine Inch Nails’ debut album in terms of its relationship to the industrial genre. Remember that social negotiations determine genre as much as musical ones do, and so we’ll start by looking historically at how Pretty Hate Machine and Nine Inch Nails were publicly conveyed to industrial audiences. This approach offers the added clarity of largely removing Trent Reznor himself from the needlessly loaded debate of whether Pretty Hate Machine’s tuneful pop structures are a subversive victory for industrial music or its death knell.

Reznor had slummed around Cleveland playing in synthpop bands for a few years when he started writing and recording angry dance music with an E-mu Emax SE synth and a Mac Plus during the unscheduled nighttime hours at the Right Track, a studio where he’d gotten a job as a technician. In an uncommon move within industrial music, the twenty-three-year-old hired a manager in 1988, figuring that he’d “put out a twelve inch on some European label [and] see what happens,” but Reznor found himself with more options than he’d anticipated for his Nine Inch Nails project—essentially a solo endeavor. His demos caught the interest of eight labels, from majors like Warner Brothers to industrial home bases Nettwerk and WaxTrax! both of whom offered deals, but ultimately Reznor took a gambit by signing with TVT Records.1 TVT had previously been a label for novelty albums of television theme songs and a few eclectic releases (notably the Connells and the Timelords—aka the KLF), but the odd little company enticed Reznor with their willingness to shell out money to hire his favorite producers and send him to Boston and London for recording. These extravagances weren’t entirely unheard-of within industrial music—WaxTrax! flew Jourgensen and his entourage overseas semiregularly—but by doing this, TVT immediately placed Nine Inch Nails in a cadre with Front 242, Ministry, and Skinny Puppy well before their debut album was even made; such was the negotiating power that Reznor had leveraged along with his manager John Malm Jr. Prior to the album’s release, there was an understanding among those in the know that it was poised to be big. Certainly Reznor was aware of the possibility, having at the time referred to himself in a letter to TVT president Steve Gottlieb not so humbly as “Your Paycheck.”2

When Pretty Hate Machine dropped in late 1989, Reznor and Gottlieb were already having big interpersonal troubles, but TVT nonetheless prioritized the record, marketing it aggressively with television spots, radio servicing, and vast print advertising. Sean Roberts, who worked sales and marketing for TVT (after a short stint with WaxTrax!), affirms, “A lot of NIN’s early success was—I hate to say this—due to what TVT did for Trent.”3

All this publicity is evidence that TVT and Reznor’s manager wanted to find a fan base beyond the industrial world. Reznor himself sells the talking point in a 1994 interview: “We have very little to do with [industrial music] other than there is noise in my music and there is noise in theirs.”4 Exasperated, he adds, “I’m so tired of thinking about it can’t even tell you.”5 But consider that he said this at the steepest moment in his fame’s ascent; as this book’s introduction notes, once musicians reach a critical level of popularity, delimiting their genre means limiting their sales, and so it was strategic for Reznor to issue this denial. Pushing implicitly against the public power of fans and media to dictate Nine Inch Nails’ genre, Reznor apparently situates sound and music as central to his supposed nonindustrialness. In contrast, by 2005—a very different moment in his career—he acknowledges retrospectively:

I felt like I was part of the scene, certainly as a fan of the WaxTrax! stuff and Ministry and Skinny Puppy and all the classics. And that was the music that I related to on a number of levels—I liked the sound of it, I like the way it was made, I liked the message, which seemed fresh at the time.6

In a revealing counterpoint to his 1994 protestation, this recognition of industrial kinship is expressed entirely in social measures: a sense of belonging, fandom, and relating. In this odd way, both comments serve to reinforce a social alignment of Nine Inch Nails with industrialism.

So regardless of how Pretty Hate Machine actually sounded, Nine Inch Nails’ image was publicly and socially constructed as industrial, and Reznor’s initial burst of in-scene activity makes it easy to see why. In 1988, he had thrown together a live band (sans guitarist) and rehearsed a handful of times at the Phantasy nightclub in Cleveland before playing ten shows with Skinny Puppy—a gig secured with help from Nettwerk Records, whose offer of a record deal Reznor and Malm were weighing at the time. Once the album came out, Nine Inch Nails toured with opening acts such as Meat Beat Manifesto, Die Warzau, and Chemlab. Reznor spent a day or two recording in Chicago with Martin Atkins’s industrial supergroup Pigface (along with Steve Albini, En Esch, Paul Barker, and others) and also put in some work with Ministry side projects Lead Into Gold and 1000 Homo DJs. Through visibly aligning himself thus with industrial bigshots, Reznor secured an important foothold with the scene’s musicians and audiences alike: in a career plan to accumulate fans and allies eventually across genres and subcultures, the easiest converts at this early stage were the people already in the industrial community. This was how Nine Inch Nails’ music got grouped alongside that of older industrial ideologues in clubs and record stores—even if their similarities were sonically limited, politically nonexistent, and, in light of the tension between Reznor’s management strategies and the industrial tenet of organizational autonomy, economically out of whack.

We shouldn’t chalk the popularity of Nine Inch Nails entirely up to marketing, management, and the savvy navigation of subculture. Their live shows, for example, eventually gained a reputation for mixing punkish kinetics and spooky atmospherics, complete with artsy backing films. In particular, the band’s performances during the first Lollapalooza tour of the United States in 1991—a gig that TVT facilitated and that Reznor initially balked at—popularized them to a wide hard rock audience.7 Pretty Hate Machine’s 1992 metal-tinged followup EP Broken acknowledges this in its liner notes: “The sound on this recording was influenced by my live band in 1991.”8

But going further back to Reznor’s demos for Pretty Hate Machine, we know there must have been something in those recordings that all those courting labels heard as marketable. It’s therefore worth moving beyond the album’s strictly social history and asking what Pretty Hate Machine’s music specifically offered that was otherwise not readily available to the would-be industrial fans of suburbia. This alchemical something derives both from the industrial dance of WaxTrax! circa 1988 and the emasculated abject of Skinny Puppy’s fluidity—all seasoned with a taste for corporate new wave and a pseudoclassical interest in modality. Understanding it more specifically starts with a look at the music’s harmonic features.

Around the time of Pretty Hate Machine’s release, most industrial music fit into a narrow range of harmonic practice. The genre’s emphasis on process, repetition, and the timbres of found sound and distortion all downplay the role of traditional melody and harmony, and inasmuch as industrial music is at heart a modernist endeavor, its suspicion of goal-oriented chord progressions and tunefulness makes sense. Recall from Chapter 3, however, that actual atonality in industrial music is rare, despite the word’s common misuse in the industrial community (for example, a 1985 issue of the zine Artitude describes Hunting Lodge’s catchy “Soul Vac” as atonal, even though it’s unambiguously in B minor).9

The most common harmonic approach in industrial music is stasis. As a general rule, a given repeated pattern in the genre’s music uses just one or two chords. There are countless illustrations from this era, but give a listen to some high-profile examples. The opening song of Front 242’s 1988 Front By Front album, “Until Death (Us Do Part),” uses precisely one chord, C minor, through its entirety, over a looped bassline. Ministry’s classic “Thieves” from their 1989 The Mind Is A Terrible Thing To Taste shifts gears rhythmically from section to section, quadrupling its tempo, but of its 138 measures 118 are all on the same E minor chord (the other 20 are on F). Al Jourgensen sings only one note, G, throughout the whole song. On the same album, “Burning Inside” has all but eight measures with A minor on the downbeat, and “Dream Song” never once departs from B-flat minor. Skinny Puppy’s Too Dark Park album of 1990 features the harmonically static “Convulsion” (not once leaving G-sharp minor) as well as “Grave Wisdom,” which holds steady on D minor for all but six measures. Einstürzende Neubauten’s brilliant 1989 club hit “Haus Der Lüge” is similarly singleminded, never fundamentally altering its D minor stomp.

In nearly every case, industrial songs are in minor modes, usually either Aeolian (using pitches in the natural minor scale) or Phrygian (like Aeolian, but with a flatted second note that pulls downward). Musicologist Karen Collins goes to great lengths to show that these modes typically connote the mythic, the mournful, and the technological. The music’s tonal stasis also aligns with what she calls the genre’s harmonic predilection for the “megadrone” and the “persistent pedal point”: “The sound could be said to resemble a bell tolling, or a heart beat, but is perhaps most clearly like footsteps.”10* Her mentor Philip Tagg has shown this practice to connote all things “large, heavy, dark, catastroph[ic], threatening, ominous, brutal, unremitting, intractable, slow, and unpleasant.”11

On Pretty Hate Machine, Nine Inch Nails present alternatives both to the harmonic stasis and to the rigidly minor modality of industrial music. Though some tracks on the album do focus on stasis or two-chord alternation (“Sanctified,” “Ringfinger”), other important moments are based on four-chord patterns, which are the bread and butter of pop music from doo-wop to Depeche Mode. This offers greater tonal variety over a short time span, which inflects melodies with more tendency, tension, and expectation. This hearkens back to a tradition of classic pop in which harmony is the songwriter’s primary means of shaping resolution, reward, and narrative. Important parts of Reznor’s songs “Sin,” “That’s What I Get,” and “Terrible Lie” are all built on compellingly poppy cycles of four chords.

Reznor is also keen on mixing modes, hinting at major and minor inflections of the same key in sometimes peculiar juxtaposition. Some of his deviation from strict Aeolian and Phrygian writing is blues-derived, like most of the hit “Head Like a Hole”; other pitch-based gestures are more exotic. In “Sin” and “Something I Can Never Have,” he crushes the major third scale degree simultaneously against its minor version, giving a sense of overripeness and self-contradiction. You can hear it in each song’s chorus: a grainy tension between Reznor’s voice and the synth parts.

It gets stranger. Reznor’s “Big Whole mix” demo of “Down In It” prominently highlights a whole-tone scale, a peculiar artificial mode used by early-twentieth-century composers such as Stravinsky and Debussy. On later recordings like “La Mer,” Nine Inch Nails would explore these ideas even further.

Pretty Hate Machine’s harmonic and melodic features owe both to Reznor’s schooling in jock-pop bands and to his classical curiosity. Some of the album’s idiosyncratic pitches clash badly against industrial music’s antipop tendency of stasis, while others manage to impart the genre with a lasting melodic vocabulary audible in the chromatic synth playing of bands such as Haujobb and Oneiroid Psychosis, respectively channeling watery impressionism and gothic eeriness. The most blatant copycat use of Nine Inch Nails’ harmony comes from the industrially tinged rock bands who found brief popularity in the second half of the 1990s. To offer a particularly telling example, compare the original melody in New Order’s 1983 synthpop classic “Blue Monday” with the melody that the band Orgy used on their 1998 cover of the song. On the lyric “I thought I was mistaken,” Orgy diverges from the original tune, briefly suggesting a major key within the overall minor milieu. It is the sound of New Order refracted through the lens of Nine Inch Nails. The melodic gesture is unmistakably Reznoresque, and it has become part of the language of industrial music, and indeed of rock at large.

The identity markers of Nine Inch Nails extend beyond the notes of the music. One of the band’s devotees interviewed in Daphne Carr’s book, Greg from Cleveland, notices a certain emphasis in Reznor’s lyrics: “When you’re singing a song with ‘I’ and ‘you’ in it, if it conjures an emotion that people can relate to, it’s almost like it’s your song.… Trent’s lyrics do that.”12 Greg hints here that “people can relate” to Nine Inch Nails’ songs because they come across as personal—an attribute that not much industrial music of the 1980s shares. To illustrate what a significant departure this album was from its industrial forebears, consider a statistical analysis of its lyrics. As it turns out, Reznor uses “I” and “you” with overwhelmingly greater frequency than other industrial bands. More broadly, by considering an artist’s lyrical use of personal pronouns, we can get a numerical impression of how “personal” an album is.

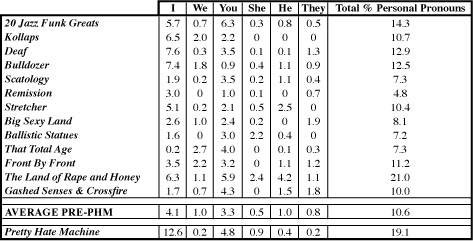

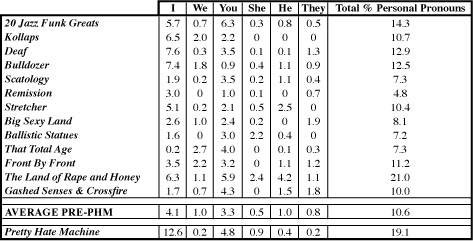

In Figure 16.1, the printed lyrics of Pretty Hate Machine are compared with thirteen earlier records that are foundational to industrial music: Throbbing Gristle’s 20 Jazz Funk Greats (1979), Einstürzende Neubauten’s Kollaps (1981), You’ve Got Foetus On Your Breath’s Deaf (1981), Big Black’s Bulldozer (1983), Coil’s Scatology (1984), Skinny Puppy’s Remission (1984), Severed Heads’ Stretcher (1985), Revolting Cocks’ Big Sexy Land (1986), A Split-Second’s Ballistic Statues (1987), Nitzer Ebb’s That Total Age (1987), Front 242’s Front By Front (1988), Ministry’s The Land of Rape and Honey (1988), and Front Line Assembly’s Gashed Senses & Crossfire (1989).* Personal pronouns have been grouped broadly into the headings I, we, you, she, he, and they; all numbers are percentages based on the total word count of a record’s lyrics, which fall between 500 and 2,400.**

First note that the total of Pretty Hate Machine’s lyrics that are some kind of personal pronoun is 19.1 percent—nearly twice the other albums’ collective average of 10.6 percent. Only Ministry’s The Land of Rape and Honey (certified gold by the RIAA) tops that number.

When we look at the use of “I” in particular, though, the difference between Pretty Hate Machine and the rest of this representative cross-section becomes much clearer. If word usage is any indicator, Reznor sings about himself over three times more often than the industrial norm. More than one out of every eight words on Pretty Hate Machine invokes the first person.

This is markedly different from what happens in other industrial music. Consider Nitzer Ebb’s classic That Total Age, whose paltry 0.2 percent incidence of first-person pronouns comes from just four uses of “me” and, amazingly, not a single instance of “I.” In comparison Pretty Hate Machine has 40 mentions of “me” and invokes “I” an egomaniacal 157 times. In this case, we might attribute this to Nitzer Ebb’s use of the imperative “you” and the collective “we,” both of which reinforce their callisthenic military image. Alternatively, Skinny Puppy’s near-total avoidance of any personal pronouns on Remission is readable as a move away from personhood itself (into monstrosity, perhaps?). Going further, we might see Einstürzende Neubauten’s texts as a reflection of Berlin’s aesthetic of cramped isolation, where I, you, and we exist, but not she, he, and they: there is no outside.

There’s also a dialectic of gender going on. Though explicit references to “him” and “her” are generally uncommon across these recordings, male pronouns show up twice as often as female pronouns in pre–Pretty Hate Machine lyrics. Similarly noteworthy but not appearing on the chart is that these records collectively mention “man” and “boy” (along with their plurals) fifty-five times, compared with ten mentions of girls, one of women, and two of bitches. Reznor flips this bias, favoring female pronouns by a factor of two, most notably on “Sanctified”—a love song to a girl, or perhaps a drug.

Thus at the lyrical level, the tone that Pretty Hate Machine offered was strikingly new within the genre at the time. It’s an album about people as they relate to each other, one-to-one. It opens itself to the “I” and “you” dialogue that fans such as Greg in Cleveland can plug themselves into. It makes room (if not political equality) for the subjectivity of listeners across the spectrum of gender.

The female space in Nine Inch Nails’ music and fandom extends beyond Reznor’s lyrical word counts. Although Skinny Puppy give voice to a monstrous gothic that erodes the maleness of all involved, offering, as Anne Williams says, “a kind of vicarious contemplation of patriarchal horrors,” Reznor presents himself as a clear-cut heterosexual masochist with remarkable consistency.13 Of the nine music videos he released from 1989’s “Sin” to 1994’s “Closer” eight portray some kind of sexualized bondage; he longs for “your fist” and “your kiss” in “Sin,” and he won a Grammy for declaring “I have found you can find happiness in slavery.”* This inflection of abjection and the gothic, according to feminist scholar Carol Siegel, “allows for identifications that disrupt the idea that the victim must always be female and that sadistic pleasure must always involve thrilling to the spectacle of a woman’s pain.”14 Both the literary gothic and the modern subcultural goth scene are expressly concerned with sexual otherness and ambiguity, Siegel argues. To this effect, like KMFDM’s En Esch before him, Reznor’s adoption of fishnet stockings and go-go shorts onstage circa 1994 probably functioned more as a queering of gender binaries than a dominant restaging of oppression (which is how some have read the spandex-clad hair metal scene of the late 1980s). However, this kind of performance does behave similarly to hair metal in that the visual questioning of totalizing masculinity functionally opened doors to female fans.

Chris Connelly calls Pretty Hate Machine“industrial music for your girlfriend,” and indeed Nine Inch Nails resonated with more women than even Skinny Puppy had. But this isn’t only by way of a sexualized, submissive self-presentation; nor does Reznor’s collaboration with Tori Amos on her Under the Pink album account for the number of the band’s female fans. Instead, Pretty Hate Machine’s “pretty”-ness and its lyrical emphasis on the personhood of everyone involved serve to address the listener as an individual. Music by Laibach and Manufacture intentionally speaks with a one-way broadcast of unassailable authority, and in doing so it necessarily addresses a paralyzed mass audience. This denial of individuality is built into the mechanization and the totalitarian imagery that characterizes so much industrial music. In contrast, Pretty Hate Machine speaks—and sometimes whines—with the voice of a single heartsick suburban kid; the album’s audience, then, is not a proletarian mass but instead likely just another heartsick kid. Probably a girl. Maybe you.

With this potential for mass appeal and the marketing push that TVT offered Reznor, Pretty Hate Machine crept steadily beyond the borders of the industrial scene, with high school outcasts, tech-savvy thinkers, and hip MTV viewers latching on to the record. This happened first in America, culminating with the band’s twenty-five successful gigs on the first Lollapalooza tour in 1991; partially in light of the band’s success, the festival would take on a token industrial act for the next few years, with Ministry in 1992 and Front 242 in 1993. The Nine Inch Nails buzz then spread to Europe, where following Lollapalooza the band opened up for Guns ‘n’ Roses on tour. Pretty Hate Machine was certified gold more than two years after its release, but long before that day it had both saturated and exposed the industrial scene.

Major labels quickly decided they wanted a piece of this action. The gold rush on industrial bands came “because Trent and Nine Inch Nails had started to break—Pretty Hate Machine,”15 confirms Sean Roberts. “Labels did what they did, which was, ‘Get me one of these. Get me an industrial band.’ There were so many at the time, but unfortunately most of them were on the same label.”16 That label was WaxTrax!

WaxTrax! played loose with paperwork, especially when it came to the Chicago-based artists whom they considered family. The price of Jim Nash and Dannie Flesher’s familial bond of trust was that they risked losing their musicians to major labels who wanted to cash in on industrial music, the “Madchester” boom, or the surprising breakout success of Depeche Mode’s 1990 Violator album. Taken together, the blows that the WaxTrax! roster suffered in the early 1990s are gut-wrenching.

Some of the label’s losses were through licensing deals. In 1990, Sony/Epic picked up Front 242 as their own EBM act, taking away Nash and Flesher’s top seller. Stunned and angry over the loss, Nash severed ties to Play It Again Sam. That same year, Al Jourgensen’s bands had collectively sold 350,000 records; sniffing the money, Sire/Warner Brothers leveraged his contract in 1991 to buy out the entire stable of Ministry side projects once and for all.17 Relations between Jourgensen and WaxTrax! had been uneasy ever since the budget for Revolting Cocks’ “(Let’s Get) Physical” single and Beers, Steers, and Queers album had ballooned more than threefold to $30,000 in early 1990, owing heavily to copyright troubles over the band’s covering Olivia Newton John’s hit.18

Out of necessity then, WaxTrax! was increasingly putting more eggs in fewer baskets. Take the example of My Life With the Thrill Kill Kult’s 1991 Sexplosion! album. Shortly before its release, Nash told the Chicago Tribune, “I expect and hope it will account for 33 percent of my revenue this year.”19 He and Flesher put considerable promotion behind the release of Sexplosion!—even hiring an outside marketing agency for its publicity. Six weeks after its June 1 release, the record was selling impressively well, having moved more than sixty-one thousand units (as compared with the forty-one thousand that their previous effort, 1989’s Confessions of a Knife, by then had sold).20 But the record’s success made the band too tempting for major labels to ignore, and they signed with Interscope Records in mid July, even as they toured for their WaxTrax! release. If it hadn’t been Interscope, it would have been someone else; the aforementioned Chicago Tribune article notes, “Warner Brothers and several other major labels are courting Nash in an effort to get their hands on records by as many as five Wax Trax artists each year.”21 It was during one such effort—a visit to WaxTrax! from Atlantic Records’s A&R team—when it slipped that the label operated on handshake deals without enforceable contracts. Though the majors had previously looked into buying WaxTrax! outright in order to acquire certain acts, from that point on they knew it was just as easy to snipe the bands directly. According to Flesher, bands “would leave the label after I poured in $100,000 for their latest tour.”22

The label’s shoddy paperwork meant not only that it lost bands, but it leaked money. A lot of cash was coming in, but most of it was kept at the physical store, where staff, musicians, and their nameless friends were freely dipping into the register. The volume and sloppiness of the sales made it hard for WaxTrax! to know how many copies any release sold, how much was owed to the artists (Nash and Flesher often erred on the generous side), and how much was reasonable to budget for the advance costs and promotional expenses for upcoming records.

Like most other industrial labels, WaxTrax! also lacked bureaucratic savvy. Employee and eventual vice president Matt Adell handled some of their business and legal affairs in the early 1990s, but in his own words, “Everything [was] done wrong.… And the things that weren’t done wrong were done totally differently than the industry tends to do them.”23 In fact it’s safe to say that the staff and artist roster generally resented the very presumption of law’s necessity. Nash’s fondness for intentionally bad taste and his disdain for contracts were a good match for the largely anarchistic music WaxTrax! put out. But as media scholar Stephen Lee writes, when the organization was in desperate straits over money and contracts, “Wax Trax’s employees faced a crisis of contradictory belief systems. They actively attempted to recontextualize both their company’s business practices and the ideological readings they brought to those practices.”24 These attempts were basically unsuccessful, because the company’s choice was one of clinging to its misfit familial identity while bleeding money at a lethal rate, or staying afloat by conforming to the dictates of big business and law—both among the vilest of the pan-revolutionary’s enemies.

On one hand, when WaxTrax! tried to persevere in its anarchic idealism, the results were often disastrous. A telling example of this was the release of KMFDM’s 1990 Naïve album, which Nash and Flesher had hoped would be the band’s breakthrough record in the wake of their tour with Ministry. The album’s cover, cartoonishly drawn by Aidan “Brute!” Hughes, depicts a grinning man having sex with a terrified woman, naked with a nipple in full view. Hughes maintains that the depicted woman’s fear is not on account of rape (as most interpret the drawing), but of the nuclear bomb exploding in the scene’s background. Either way, the label didn’t want to limit the band artistically for their questionable taste, but as former label manager John Dennett sighs, “That nipple kept it out of all the major stores.”25 Although WaxTrax! may have scored a vague moral victory in its decision to respect KMFDM’s artistic freedom, not only did they lose valuable sales, but amidst the internal struggle over Naïve’s cover art WaxTrax! and KMFDM crucially failed to address an uncleared sample of the famous “O Fortuna” from Carl Orff’s 1936 Carmina Burana that appeared on the album’s seventh track “Liebeslied”—a legal oversight that resulted in the album being deleted altogether under threat from Orff’s publisher. The record failed to give KMFDM the breakthrough they’d hoped for, not only because of its cover art and its deletion but also from the bad planning of its release during the Christmas season, when kids stop buying albums in the hopes that their parents will give them the ones they want—and parents opt for safe bets over unknown, nearly pornographic ones. In Dennett’s hindsight, it was “a really dumb time to release a record.”26 WaxTrax! had projected 44,000 sales of Naïve, but a year after its release the album had moved just 22,528 copies.27

On the other hand, when WaxTrax! tried to play by the conventional rules of law and finance, it rang sour with the label’s artists and its conscience. After losing My Life With the Thrill Kill Kult, WaxTrax! hired an outside consultant to help them computerize their records, draw up contracts, and compute sales projections and budgets for each release. This meant that employees (Dennett and Adell) had to convince the label’s longtime family to sign contracts that damaged the implicit trust on which the whole operation was based—a trust that was already compromised by the first bands’ leaving. These contracts were also not nearly as generous as the verbal deals Nash and Flesher had once offered. Chris Connelly remembers it was

something they were making all of their artists do as the label’s profile had grown. The lights illuminating the roster had brightened, and major labels were sniffing around, signing up many of the acts and there wasn’t a lot Jim or Danny could do. Along with the heightened popularity of the label, there came a new crop of employees; a cloying, mealy-mouthed bunch who fancied themselves on the cutting edge of the business. They were full of casual put-downs of us old-guard, apparently the future lay with the young hotshots they were signing—laughable, as not one of the acts they signed ever went anywhere.… I signed, of course, like an idiot, there was no excuse except it was under duress.28

The acts that Connelly refers to were mostly techno groups. Nash and Flesher’s roots had always been more in disco than the Death Factory, and when Meat Beat Manifesto jumped ship to Elektra Records complaining that they had been unfairly labeled “industrial,” the label’s heads admitted that they felt some empathy. Journalist John Bush says of Meat Beat Manifesto’s alleged industrialness, “Simply appearing on Wax Trax! Records was enough to do the trick,” but if industrial acts were now signing on with major labels, then WaxTrax! didn’t have much bargaining power to land new ones, and so Nash and Flesher attempted to invest in their longevity by signing dance musicians whose style had not quite yet become the Next Big Thing.29

Even when this idea seemed like it might work, though, the company still ran into trouble. Their biggest success in this new crop was the KLF, a radically political UK acid house act who had bounced around a few U.S. distributors, including TVT. Their 1991 Euro-dance single “What Time Is Love (Live at Trancentral)” found its way into the hands of DJs and tastemakers (via non-WaxTrax! import sales) even before its official U.S. release. The buzz surrounding the song was tremendous, but because WaxTrax! hadn’t projected sales figures, “We couldn’t supply demand on any level,” says Dennett.30 The label had bad credit with its manufacturers, meaning that they were unable to place large orders; “On a retail level, we couldn’t produce enough copies. Four or five thousand copies would come in from the manufacturers and would be shipped pre-sold.”31 WaxTrax! ultimately managed to print and sell thirty-five thousand copies of the single, but the band left the label for Arista, where their next two releases both went gold in the United States and charted top five in the UK.

WaxTrax! soldiered on under their new, businesslike approach, and they did manage to push KMFDM’s profile a bit higher in 1991 and 1992 (despite the band having nearly broken up in that period). They also scored a minor hit with the debut album by the bluesy industrial rock act Sister Machine Gun. By this time, though, Nash had actively been trying to sell the whole label to a major in hopes of ending his business headaches so he could focus on A&R. Interscope had recently bought up all of TVT just to get Nine Inch Nails, and New York–based Roadrunner Records bought a 50 percent stake in Gary Levermore’s Third Mind label, so Nash’s hope was that WaxTrax! could bargain with its back catalogue and its admittedly reduced stable of artists. With the help of Jourgensen, a deal had almost come through with Sire Records in late 1990 but then collapsed. Similar near misses occurred with Zomba, Restless, and Island Records. Failure after failure to save the company effectively destroyed the morale among staff and artists. In looking back on the close of 1991, Chris Connelly says, “It was definitely the end of something.”32 Even the ever-loyal KMFDM, whose frontman Sascha Konietzko was personally renting his apartment from Nash and Flesher above the WaxTrax! store, began negotiating with Interscope in 1992. In a last-ditch effort to free up some cash and save the imprint, WaxTrax! filed for bankruptcy on November 20, 1992. Most of the label’s staff were laid off at this point. By the year’s end, the once-independent TVT stepped in and bought the label with a production and distribution deal that left Nash theoretically in charge, but with little functional power. For the people behind WaxTrax! the label, the store, and indeed life itself was no longer the party it had been. Though he hadn’t spoken to many others about it, Nash learned in 1992 that he’d had HIV for several years; it almost certainly contributed to his desire to return to a life less nagged by the banalities of business.

If this chapter is a downer compared to the story of the wild early days of WaxTrax! then consider how one might reconcile these ruinous early 1990s with the snapshot that began this book, where ecstatic crowds in 1991 heard Front Line Assembly’s music as something entirely new. Which story of those years is the “real” one? The answer, as ever, depends on whom you ask. Scenes by definition are always host to newly energized participants.

The number and the demographics of those who’ve cared about industrial music over time—along with the ways that they’ve used the music—correspond not only to the progressive stages of its genre development but also to how it engages the recurring metaphor of the machine. This is one basis of the decline-and-fall narrative that some impose on industrial music.

The music’s early emphasis on process as a compositional method above any assessment of its sound points toward the music’s structure enacting the machine. The subsequent negotiation of the genre’s aesthetics entrenched samplers and drum machines as sonically industrial; the music was no longer a process, but a construction that connoted the machine. Once recognized as a sound, industrial music then became available as a stylistic imposition—a signatory feature to adorn songs and make them resemble the machine. From enactment to connotation to resemblance, the genre’s important signification of the machine has thus grown more distant and tenuous over time; it’s a tough fact to deny.

Socially, it makes for a disconnect between industrial generations. For example, Jason Novak and his industrial rock group Acumen (later Acumen Nation) nearly signed to WaxTrax! in 1992, and at the time they had essentially no sense of the headiness that early industrial music so explicitly emphasized.

I was not at all aware of the first wave. We always said we were industrial, but thinking about it now, we were nowhere near. What industrial music originally meant had nothing to do with what it’s identified with now. You almost have to say specifically it was industrial dance music, because with those first acts, there was no desire to pound a four-on-the-floor kick. It was about the sounds of industry; it was about the geography—taking those sound effects that they woke up to and heard in those industrial European cities or whatever. That became music. Then it was co-opted by people who wanted to put a dance beat behind it. I knew what their t-shirts and album covers looked like, but I never owned a single Neubauten record or Throbbing Gristle record until I was older and wanted to hear where some of this stuff came from.33

Not only does Novak’s experience illustrate the disconnect between industrial music’s eras, but his assumption that early industrial music’s foremost concerns were “the sounds of industry”—as opposed to the social conditions they heralded—is instructive. It demonstrates that even if young musicians of the early 1990s had been in dialogue with early industrial music, their takeaway message was sonically derived, and not the stuff of social theory. To be fair, this interpretive gap isn’t just created by time; recall Genesis P-Orridge’s perception that Whitehouse and similar bands wrongheadedly appropriated industrial aesthetics without understanding industrial politics.

This disconnect doesn’t derail industrial music’s alleged mission, because as this book has repeatedly shown, one can readily hear its ideological echoes and undercurrent encoded aesthetically. It does, however, cloud certain ideas behind a haze: rare is the musician today who articulates the pan-revolutionary with the same clarity that SPK and Nocturnal Emissions once did.

Musically, the changes over time progressed, as noted, from process to construction to songwriting. This latter approach to making music supposes that the song is separable from its production, and it was still relatively new to industrial music in 1992, partially because neither samplers nor even cheap step sequencers could easily privilege harmonic variety and large-scale form, favoring timbral variety and groove construction instead—recall the workshop mentioned in this book’s introduction on how to build an EBM track.

There’s an undeniable question of personality too. In the 1980s, musicians most interested in the craft of songwriting were seldom attracted to the strangeness and alienation that was culturally assigned to electronic music; songwriting had long been entwined with authenticity in the wake of figures such as Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, and Bruce Springsteen. “[A]uthenticity works as a strategy to mask the commercial aspects of popular music,” Nathan Wiseman-Trowse writes, and given industrial music’s frequent agenda of revealing the ubiquitous tyranny of all things commercial, it’s thus no wonder that so many electronic pop musicians in the late 1970s had fetishized glam rock, which flaunted artifice.34* Indeed, those who chose to use synthesizers were often tech heads or intellectuals uninterested in expressions of traditional authenticity, and frankly, many of them were incapable of writing what were traditionally deemed “songs”; for example, Martyn Ware says that one reason Adi Newton was kicked out of the Future in 1977 was that he “doesn’t really understand or really like pop music.”35 Electronic music’s distance from songwriting also helps explain why so many early popular synth records were cover versions: Silicon Teens’ Music for Parties, Soft Cell’s “Tainted Love,” British Electric Foundation’s Music of Quality and Distinction Volume 1, the Bollock Brothers’ Never Mind the Bollocks ’83, Giorgio Moroder’s “I’m Left, You’re Right, She’s Gone,” and even Walter/Wendy Carlos’s Switched on Bach.

But with an aura of coolness newly lit in the early 1990s, industrial music had begun attracting a varied, more “normal” clientele who were comparatively versed in traditional songwriting. Many of these musicians and fans flowed toward the industrial genre from adjacent styles like goth rock and synthpop.

We’ll come back to songwriting in a moment, and we’ll address goth music in the next chapter, but it’s worth delving momentarily into synthpop, whose early-1990s encounter with industrial music has, in retrospect, increasingly proven to be significant. Granted, there’d always been some dialogue between industrial music and synthpop—acts such as the Leather Nun and Twice a Man, both Swedish, straddled these sonic lines in the early 1980s—but a second cross-pollination in the early 1990s produced more lasting effects on industrial’s sound and creative process.

After the Futurist synthpop movement of the early 1980s was largely swept up by the major-label New Wave and Neue Deutsche Welle frenzies, a junior class of synthpop arose, savvier and decidedly swimming against the tide of the mainstream. The veil between underground electronic genres was particularly thin in Germany, where acts such as Celebrate the Nun and Camouflage specialized in minor keys and abrasively compressed percussion. These bands’ songwriting was of a sadder stripe than the pop-made-on-keyboards that characterized the chart hits of the day, and as such synthpop records circa 1990 began wallowing in timbres that connoted the weighty and the epic: faux choral synth presets, huge single-note piano basslines, sustained string sounds, and lugubrious male vocals. Just when bright, brassy pop records began dominating western airwaves (to say nothing of hair metal and rap), synthpop musicians and fans peeled away and spawned a new generation of independent acts and labels. An odd collection of lovelorn nerds started filling European goth club dancefloors whenever Wolfsheim was played, and in America the synthpop scene heavily centered on the west coast and was an unlikely meeting ground for Christian and gay youth—a curiosity worthy of a book in itself. By 1992, such acts as Anything Box and Cause & Effect had gained small but religious followings, while Depeche Mode and New Order were outright gods.

The upshot was that the tenuous lines separating EBM from other electronic dance genres further dissolved. Industrial-friendly acts such as And One and De/Vision were using the same sound palettes and song structures as synthpoppers Camouflage and Depeche Mode, and a band’s relegation to one genre or another effectively relied on how traditionally tuneful the singer was and what record label they signed with. By 2000 or so, the line between synthpop and EBM-derived industrial had in many cases fully disappeared, as acts like Seabound illustrate today.

Returning now to the idea of songwriting in industrial music, one may well recognize its ascendancy in the 1990s as a fairly direct outgrowth of synthpop’s path crossing. The interrogative chorus lyric of Die Krupps’ 1992 hit “Metal Machine Music” barks, “Why do we act like machines?”—but inasmuch as industrial music was signified in production and thus chiefly resembled the machine during this time whereas it had previously connoted the machine, and even earlier had embodied its structure, we might answer that question with the admission that we don’t, really. Not anymore.

This is one of the reasons why there is so much tension in the self-evident pleasures of the early 1990s’ rock- and synthpop-derived industrial music. It is the sound of musical honing (if not development), but industrial music’s encounter with the commercial phase of genre is so problematic in light of industrial politics that, as the next chapter explores, many felt it to be genuinely deadly.

ICONIC:

And One – “Technoman” (1991)

Ministry – “Thieves” (1989)

My Life With the Thrill Kill Kult – “Sex On Wheelz” (1991)

Nine Inch Nails – “Terrible Lie” (1989)

Nitzer Ebb – “Join In the Chant” (1987)

ARCANE:

Brighter Death Now – “Great Death” (1990)

Leæther Strip – “Antius” (1991)

Out Out – “Admire the Question” (1991)

Think Tree – “Hire a Bird” (1989)

Will – “Father Forgive” (1990)