The journey of a hormone starts with a dozen endocrine glands: your adrenal glands, pituitary gland, hypothalamus, thyroid, pancreas, and ovaries, among others. These glands control important physiological functions by releasing hormones into the blood, through which they travel to distant organs and cells. In other words, hormones are chemical messengers, like snail mail in the body. They influence behavior, emotion, brain chemicals, the immune system, and how you turn food into fuel.

For instance, the adrenal glands produce cortisol, one of the most powerful stress hormones. Cortisol, in turn, directs your body on how to react in times of stress—more on this later. The ovaries, which are mostly silos of eggs, produce many hormones, including estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone. (These are referred to as sex hormones because they determine features such as fertility, menstruation, facial hair, and muscle mass.) The pancreas secretes insulin, which has the primary job of moving glucose into your cells, thereby lowering the glucose in your blood. Fat cells are the largest endocrine gland in the body: fat secretes hormones such as leptin, which regulates appetite, and adiponectin, which adjusts how you burn fat.

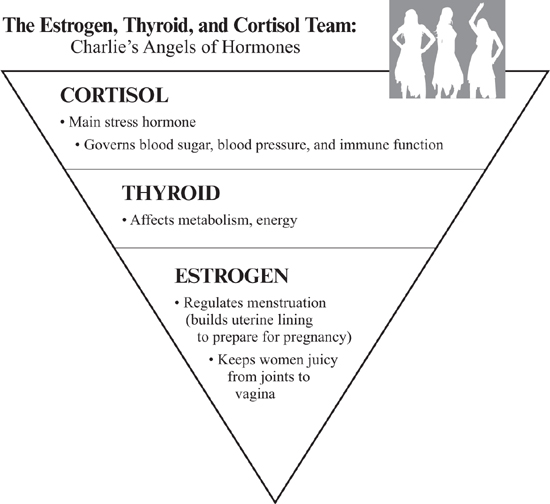

Each hormone has a job. Figure 1 (page 44) shows the top three hormones for women: estrogen, thyroid, and cortisol—the major hormones that affect your brain, body, stress, and weight. Cortisol is your main source of focus and function when you are under acute stress—but when you’re chronically stressed, your levels may ricochet from too high to too low. Thyroid affects your metabolism, keeping you energized, comfortably warm, and at a manageable weight. Estrogen is actually a group of sex hormones responsible for keeping women juicy, joyous, and jonesin’ for sex.

I’ve listed the most important jobs for your top three hormones, but keep in mind that there are many more. For instance, estrogen has more than three hundred jobs or biological tasks in the female body, and influences more than nine thousand genetic messages that your body sends out to regulate itself.

In addition to the three primary hormones in Figure 1, several other hormones play important roles in driving your interests, mood, libido, and appetite. Progesterone counterbalances estrogen by helping regulate the uterine lining (i.e., keeps the lining from getting too thick), emotions, and sleep. Testosterone is the hormone of vitality and self-confidence—and producing too much is the main reason for female infertility in this country. Pregnenolone, the lesser-known matriarch of the sex-hormone system, is responsible for maintaining a facile memory and vision in vivid Technicolor. Leptin controls your hunger, determining whether you use food as fuel or store it in your midsection; it cross-reacts with the thyroid and most of the other hormones. Insulin regulates how your body uses fuel from your food, and directs your muscle, liver, and fat cells to take up glucose from the blood and store it.

Some hormones multitask. Oxytocin is both a hormone and a neurotransmitter, which means it acts as a brain chemical that transmits information from nerve to nerve. Some call oxytocin “the love hormone” because it rises in the blood with orgasm in both men and women. Oxytocin is also released when the cervix dilates, thereby augmenting labor, and when a woman’s nipples are stimulated, which facilitates breastfeeding and promotes bonding between mother and baby. Vitamin D is a hormone synthesized from cholesterol and exposure to sunlight. It can also be ingested from food, but it is not officially an essential vitamin because it can be made by all mammals exposed to the sun. (A molecule is considered an “essential dietary vitamin” when it is necessary for the body to function but cannot be produced sufficiently by an individual and must be consumed from food or taken as a supplement.)

Figure 1. The Estrogen, Thyroid, and Cortisol Team: Charlie’s Angels of Hormones. Your most essential hormone is cortisol, the main stress hormone, which will be produced in your adrenal glands under most conditions, stressful or not. Thyroid is the next most important hormone, and of the three, estrogen is considered less essential than the cortisol or thyroid hormones, since you don’t need to ovulate to survive.

Your brain is the locus of control; it is in charge of when and how these hormones get released. As you will learn in future chapters, feedback loops between the brain and hormones are involved in this process to help your body stay in balance. Additionally, several hormones influence one another with cross talk.

Your cells are perpetually bathing in a broth of various hormones. In women, the broth changes on a daily, and even minute-by-minute, basis, depending on factors such as whether you are menstruating, how long it’s been since your last period, the amount of stress you sense in your environment, what you eat, how much you exercise, and whether you are pregnant. Your cells have receptors, which respond to specific hormones. Receptors are like locks on a door. The hormone fits into the lock to open the door. For example, when you face danger, the main stress hormone, cortisol, fits into the lock in a cell and opens the door to generate a burst of glucose, which enables you to run faster and stronger. If the cell is not designed to interact with a particular hormone, its receptor (lock on the door) will not fit the hormone’s key. Scientist Candace Pert aptly calls this process “molecular sex.” If the lock is broken—such as with insulin or cortisol resistance—likewise, the door will not open and blood levels of the hormone will rise.

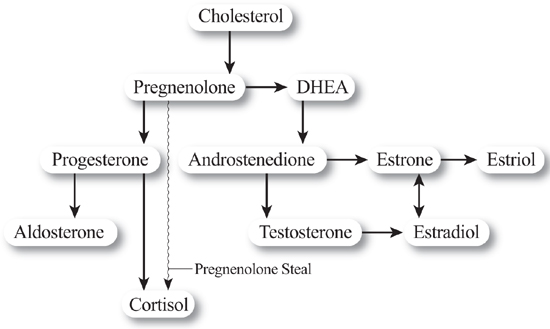

Most hormones are made in the endocrine glands from a precursor hormone, also known as a prehormone. Prehormones are the body’s efficient way of producing the hormones you most need on the fly, without starting from scratch.

Many of the common sex hormones in the human body are originally derived from cholesterol, which your body turns into pregnenolone. Pregnenolone is the “mother” hormone (or “prehormone”) from which other hormones are made. Under normal and calm circumstances in your adrenal glands, pregnenolone is converted either into progesterone or DHEA, another stress hormone and a precursor to testosterone. When you are chronically stressed, you make more cortisol—it gets stolen from pregnenolone and other hormone levels may fall—a process called Pregnenolone Steal. Of course, not all hormones are derived from cholesterol (more on that later!).

Figure 2. Hormone Tree: Pathways of Selected Hormones (How Sex Hormones Are Made in Your Body). In your adrenals and ovaries (and fetus/placenta when pregnant), cholesterol is converted into several hormones. The hormones listed in this figure are called sex steroid hormones because they are derived from cholesterol’s characteristic chemical structure and influence your sex organs (note that other hormones, such as thyroid and insulin, are not sex steroid hormones and are produced elsewhere). Further subclassification or families of hormones that you may encounter include the following. Progesterone is part of the mineralcorticoid family (affects salt—mineral—and water balance in the body), whereas cortisol is a member of the glucocorticoid family (glucose + cortex + steroid; made in the cortex of the adrenal glands, binds the glucocorticoid receptor, and raises glucose, among other tasks). Testosterone is a member of the androgen family (made by men and women; responsible for hair growth, confidence, and sex drive); and estradiol, estriol, and estrone are members of the estrogen family (sex steroid hormones produced primarily in the ovaries to promote female characteristics such as breast growth and menstruation).

When your hormones are in balance, neither too high nor too low, you look and feel your best. But when they are imbalanced, they become the mean girls in high school, making your life miserable. Here’s the good news: realigning your hormones is a lot easier than running around like a crazy person, depleted and anxious about the little things in life.

Here are the top hormone imbalances I see in my practice:

• High cortisol causes you to feel tired but wired, and prompts your body to store fuel in places it can be used easily, as fat, such as at your waist.

• Low cortisol (the long-term consequence of high cortisol, or you might have high and low simultaneously) makes you feel exhausted and drained, like a car trying to run on an empty gas tank.

• Low pregnenolone causes anomia: trouble finding . . . what’s that again? Oh, the right word. Low levels are linked to attention deficit, anxiety, mild depression, brain fog, dysthymia (chronic depression), and social phobia.

• Low progesterone causes infertility, night sweats, sleeplessness, and irregular menstrual cycles.

• High estrogen makes you more likely to develop breast tenderness, cysts, fibroids, endometriosis, and breast cancer.

• Low estrogen causes your mood and libido to tank and makes your vagina less moist, joints less flexible, mental state less focused and alive.

• High androgens, such as testosterone, are the top reason for infertility, rogue hairs on the chin and elsewhere, and acne.

• Low thyroid causes decreased mental acuity, fatigue, weight gain, and constipation; long-term low levels are associated with delayed reflexes and a greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

More often than not, I care for women who have more than one hormonal imbalance. Here are the most common combinations of hormone imbalances I see in my practice. (Read more about these and other common hormonal combinations in chapter 10.)

• Dysregulated (high and/or low) cortisol with low thyroid function. (Here I define dysregulated to mean that the body’s response to chronic stress is poorly modulated, or regulated, such that cortisol is not kept within an optimal range for the body and is either too high or too low, usually at different times within the same twenty-four-hour period.)

• Dysregulated cortisol with dysregulated sex hormones (estrogen and progesterone).

• Women in their thirties will often have symptoms of low progesterone and high androgens, and wonder why it’s taking so long to get pregnant.

• Women in perimenopause, which starts sometime between ages thirty-five and fifty, have low progesterone, and in the final year before their final period, low estrogen. They experience low progesterone as anxiety, sleep disruption, night sweats, and shortened menstrual cycles—and fret over work and field trip permission slips in the middle of the night. Low estrogen may add mild depression to the mix.

• Women in menopause commonly have low cortisol during the day (which makes them feel tired) and high cortisol at night, which makes them worry about everything from the stock market to whether their children are exposing themselves to sexually transmitted diseases or finding their dream job.

In addition to pregnancy, the most common, and often overlooked, causes of any hormone imbalance include:

• aging

• genetics

• poor nutrition and/or inadequate “precursors” to make hormones

• environmental exposure to toxins

• excess stress

• lifestyle choices

The main thing you need to know is this: a hormone does not exist in a vacuum. Some hormones dramatically affect other hormones; high levels of one can interfere with the action of another. When you’re chronically stressed, for instance, your levels of cortisol go up, and if they rise too high, they can block cells from getting progesterone, which calms you down. As described above, hormones fit into the receptor on a cell like a lock into a key, in a process that we identified earlier as molecular sex. If cortisol is busy having molecular sex with the progesterone receptor, the lock is occupied and unavailable to another hormone, and the progesterone molecule can’t get into its own receptor. Even if your blood progesterone levels are normal, you may feel progesterone deficient, which means you might have trouble becoming calm or getting pregnant. Because of these interrelationships, it’s crucial to treat multiple symptoms at the same time.

Many hormones, including cortisol and thyroid, are controlled by a feedback loop that shuts off production when levels get high. In addition to interaction with one another, the hormones interact with and depend on the light/dark cycle in the natural world. For instance, cortisol levels peak after the sun comes up (after seven a.m.), and melatonin gets suppressed. Conversely, at nine p.m., ideally you make more melatonin as cortisol levels decrease.

Why do these things matter? When you understand how your hormones interact with one another, it’s easier to find hormonal harmony. When you assess and treat multiple hormonal systems—the adrenal, thyroid, and sex hormones, in particular—at the same time, you get better and faster results.

One word of caution: the “solution” with wayward hormones is more nuanced than simply slapping more hormones on the problem in order to effect a cure. This is because of hormone resistance (including cortisol, progesterone, and thyroid resistance, which I’ll explain later); genetic predispositions; and the complexity of downstream chemicals made from the major hormones considered in this book.

For instance, PMS is related to a problem with progesterone, but frosting yourself in progesterone cream does not automatically fix the symptoms in all women. Our best science shows that PMS is the result of the poorly synchronized interplay among four entities: progesterone, allopregnenolone (a derivative of progesterone), and in the brain, the GABA and serotonin pathways. It’s a complicated neurohormonal mix that results in progesterone “resistance,” which is why topping off your progesterone may not be the answer. Your body may respond better to a “cure” that addresses upstream causes—including precursors, such as vitamin B6, that help you make serotonin, or perhaps an herb that alters progesterone sensitivity, such as chasteberry, as well as lifestyle techniques to calm your brain.

Remember Charlie’s Angels—Sabrina, Jill, and Kelly, the TV trio of crime-fighting, bad-guy-busting women with brains, brawn, and physical agility? Seeing the three of them working in sync was poetry. It was empowering. So it is with your hormonal system. When the hormones work together, the team is powerful, graceful, and effective.

Bear with me as I pursue this analogy. Sabrina is cortisol. She stands up to Charlie more than the other angels do, and she’s less inclined to manipulate men with her feminine wiles. She’s the smart angel, the no-nonsense, strategic-thinking one. Just as Sabrina is the one who rescues the “angel in danger,” cortisol, coursing through your bloodstream, alerts your nervous system to threats, whether it’s an imminent car accident or a toddler heading toward a wall socket. Cortisol helps you respond to the scary effects of your everyday adventures by regulating the levels of other hormones, such as thyroid and estrogen.

Jill is thyroid. She is the sporty angel, lithe, athletic, and adventurous. Thyroid keeps you energetic, slender, and happy; it is the Jill of hormones. Without enough thyroid, you feel fatigued, gain weight, go through life in a low mood . . . and libido? Fagettabout it.

Kelly is estrogen. She is the sensitive angel: soft and voluptuous, but also street-wise and tough. She can be powerful and in control one minute, a seductress the next. This is like estrogen, which keeps you flush with serotonin, the feel-good neurotransmitter. Estrogen keeps your orgasms toe-curling, your mood stable, your joints lubricated, your sleep and appetite right, your face relatively wrinkle-free. Estrogen keeps the other angels, cortisol and thyroid, in balance.

To bust the bad guys—depression, slow metabolism, lack of energy—you need your hormonal angels working in sync. That’s absolutely pivotal for a feeling that all is right with the world. Get each in the proper proportion, and you will feel more balanced and aligned. Each hormone is important, useful, and essential on its own. But when they work together at the height of their individual powers, magic happens. Health. Happiness. Vitality. Libidic lusciousness.

A key feature of women’s hormones is that some tend to get more out of control than others. Take cortisol, for example. At chronically high levels, cortisol often behaves like a runaway train. That is, as you rush from task to task, your cortisol levels climb even higher (similar to a runaway train that picks up speed over time), causing cravings for sugar or wine, depositing more fat around your belly, and giving you a false sense of energy or a second wind. Before you know it, you’re still surfing the Internet and you have to get up for work in six hours, yet you’re so wired you can’t sleep.

When this happens, cortisol is running roughshod over your other hormones. Cortisol is the alpha hormone, and couldn’t care less about its long-term relationship with your ovaries and thyroid. So your thyroid steps in and tries to fix the problem, which results in less thyroid hormone production. When cortisol is high, it blocks the progesterone receptor, making it difficult for progesterone to perform its calming duty. Less thyroid hormone slows down your metabolism, which is the rate at which you burn calories. Now you’re tired, wired, and gaining weight.

Unfortunately, cortisol is primarily controlled by the most ancient and, we might say, less flexible parts of your brain. Some call it the reptilian brain, which developed earlier than the limbic brain and the cortex (“thinking” brain). The connections between these three aspects of the brain overlap. Structurally, the reptilian, or lower, brain includes the brain stem and cerebellum. (I prefer the term lower brain because it is more descriptive and the term reptilian gives me the creeps.) This innate, deep part of our brain biochemically controls such instinctual behaviors as aggression and dominance. It developed many ages ago, before other parts of your brain, when survival depended on running from predators such as lions and tigers. In other words, your reptilian brain is reliable but rigid, and sometimes that’s good. If someone throws a rock at your head, your lower brain will cause you to duck rapidly.

Your lower brain also shares many tasks with your limbic brain, which is the seat of emotion, learning, and memory. Limbic structures include the amygdala, hypothalamus, and hippocampus, plus several others. Your amygdala decodes emotions, including threat, which trips the body’s alarm circuits. Beyond fight or flight, the limbic brain governs mating (particularly ovulation and the sex drive). Together with the lower brain, the amygdala provides vigilance. With the help of your limbic brain, your lower brain manages such important tasks as breathing, digestion, elimination, circulation (as in, send more blood to the leg muscles so this body can run!), and reproduction.

Your thinking brain works too slowly for fight-or-flight tasks such as dodging flying objects. The problem is that your lower brain and amygdala often run the show—perpetually searching your environment, your e-mail, and your marriage for potential threats, perhaps filling in the details when the threat is vague or unclear. The vigilance centers often behave like street-wise punks, and they run the show based on thousands of years of evolution, unless you consciously change the manner in which you respond to stress. Blame it on the cortisol that surges under stress and leaves us reacting instead of reasoning.

To get our hormones balanced, we’ve got to calm down the overactive lower and limbic brain. Ultimately, hormones are far more likely to be in proportion if we are able to learn how to tolerate emotions with more equanimity, and not feel like we’re constantly dodging bullets.

Your hormones are designed to work for you, not against you. With nature’s preference for hormonal harmony, it’s easier to be in balance than to remain out of balance. But an interloper—your lower brain—keeps getting in the way. Fortunately, there are ways of calming down: meditation, yoga, exercise, walking in nature, therapy, and orgasm. Each person needs to find what calms her best. Yoga, meditation, hot baths, and targeted exercise, such as Pilates or power walking with girlfriends (not running, because it raises cortisol), work best for me.

You also want your circadian rhythms to be working properly and aligned to the light/dark rhythm outdoors. Nearly every hormone is released in response to your circadian clock and the sleep/wake cycle. Some of us are morning people; some are night owls. When we do shift work at night, the natural rhythms are disrupted. But the basic rule is, to the extent you can, go to bed each night at the same time, wake up at the same time, and get out in the sunshine. This creates circadian congruence, which optimizes your hormone balance naturally.

Many of my patients want to check their hormone levels first thing at a laboratory or at home, and sometimes this is helpful. Nevertheless, there are several reasons why I use questionnaires to identify your hormonal issues rather than immediately checking levels in the blood, urine, or saliva.

• Most hormones vary according to time of day, similar to a flower that opens by day and closes by night.

• Due to hormone resistance, sometimes what you feel is not reflected in the blood, urine, or saliva level of a hormone. Your felt experience correlates with the hormone levels inside your cells, and especially inside the nucleus of your cells, which is where your hormones interact with your DNA (your genetic code). You see, most hormones have receptors on the cell nucleus, and if your hormone receptors are jammed, it doesn’t really matter what your hormone levels are outside of the nucleus or outside of the cell (in the blood, urine, or saliva). Hormone resistance has been documented for multiple hormones, such as insulin, cortisol, progesterone, and thyroid.

For these two reasons, I recommend that you start with the questionnaires (rather than checking your levels and getting focused on your numbers rather than on what you are feeling), which will guide you to the appropriate chapter containing your hormonal issue. Once you identify the root cause of your hormonal symptoms, move on to the lifestyle reset in Step 1 of The Gottfried Protocol of the corresponding chapter to get your hormones back in balance again.