As we all know, life doesn’t always fit into perfect categories. More often than not, life is messy and disorganized. The same is true for hormones. Just as your health does not exist in a vacuum but is a vast interconnected web of influences and functionality, the same applies to your neuroendocrine system. While some people have one hormonal imbalance, the majority of us have some kind of combination. The point of this chapter is to provide guidance for those who have multiple hormone issues. How do you know? If you answered “yes” in the questionnaires in chapter 1 enough times to be torn between which chapter to visit first, then chances are you are experiencing one of the common combinations of hormonal imbalance. I’ve got solutions to help you optimize your health in a way that is holistic and comprehensive.

Your hormonal system communicates with your mind and the rest of your body as a complex and sophisticated neuroendocrine communication network that encompasses your brain chemicals and hormones. Specific parts of your brain—essentially, your hypothalamus and pituitary, which are part of your limbic system—are the boss of your network.

Here’s the problem: One part of your brain tends to exert more influence than any other, and that’s your amygdala, where you take in stress, interpret, and then embed news and stimuli from your environment, and manufacture your mental and emotional state. Women aged thirty-five to fifty have a tendency to overrespond emotionally to triggers in an immediate, reactionary, and sometimes overwhelming manner. There’s a mismatch between the trigger and the response. I know, because I’ve been there, and I see many women each day in my office who feel this way. Here’s how one woman describes it:

I’m so up and down with my emotions, Dr. Sara. They’re right at the surface. Discernment? Gone. Some days at work, I’m on my game and can keep it together, and other days, I burst into tears for no good reason. It’s not cool when that happens at work. It’s also not just before my period, although it’s certainly amplified. I just can’t trust myself anymore to have my act together.

It is very difficult to manage the amygdala, yet it impacts your levels of critical hormones such as cortisol, estrogen, progesterone, and thyroid. The amygdala, hypothalamus, and pituitary organize, integrate, and coordinate what you’re interested in: mood, fertility, sexual desire, skin texture, general aging, and weight via neuroendocrine communication. Your brain determines hormone levels throughout the body, and reciprocally, hormone levels direct brain activity through feedback loops—and the dance between the two determines your ability to feel optimal vim and vigor.

I’ve addressed the intercommunication of the main endocrine glands to some extent in previous chapters, but I’d like to devote a whole chapter to this crucial idea. Now that you have a sense of how to apply The Gottfried Protocol for individual hormone imbalances, I want to share with you how to deal with several hormonal issues when they occur simultaneously. As the number of symptoms rises along with the complexity and interconnections of your hormonal problems, I strongly recommend working with a trusted clinician. But here’s the good news: when you fix more than one hormonal problem at a time, you amplify both the health benefit and how good you feel.

I was taught, particularly in surgery and other areas of medicine where triage is an operative word, to prioritize the most pressing problems facing a patient, and to act on the most immediate and proven solutions. But hormones are not surgery; you are not hemorrhaging or infected. For hormonal balance, especially when more than one system is imbalanced, you need a different and more nuanced method. My patients achieve the best results when they agree to partner with me on a systems approach to why their hormones went awry, and to spend the time looking at how it all started. The root cause of your hormonal issues, particularly multiple hormone issues, tends to begin well before symptoms appear. By adjusting the levers that got you out of hormonal balance, you are more likely to experience sustained balance and restore homeostasis. The following case is a great example of what I mean.

FROM THE FILES OF SARA GOTTFRIED, MD

Patient: Jocelyn

Age: Forty

Plea for help: “I’m really tired, and feel like I have no reserve. I’m drinking more coffee to lift me up in the morning but it doesn’t seem to help, and then I have trouble falling asleep. I’m easily frazzled and can’t concentrate, especially when I’m busy and under deadline. I’m overwhelmed and it’s just not like me to feel this way. Every time my kids bring home a virus, I catch it. Exercise doesn’t feel good, and I used to be an athlete. This is new in the past few months, and it’s bringing me down. I can’t handle it! I’m not full-on depressed, but I’d like to feel more human again.”

Jocelyn took my questionnaire and checked off five signs of low cortisol: fatigue, loss of stamina, chronic overwhelm, difficulty fighting infection, and poor sleeping. She also noted three signs of low thyroid function: dry skin, brain fog, and mild depression. Given her multiple symptoms, I checked her blood for cortisol—we found that her morning level of cortisol was slightly low at 6 mcg/dL (I believe the optimal range for adults is 10–15.0)—and TSH, which indicated mild hypothyroidism at 2.7 mIU/L (I use 0.3 to 2.5 mIU/L as an optimal range). Her twenty-four-hour urine test for cortisol was normal. Her blood pressure was low normal at 92/61.

Treatment protocol: We applied The Gottfried Protocol for low cortisol and thyroid, Step 1, simultaneously. Jocelyn began a supplement regimen of a vitamin B complex, tyrosine at 1,000 mg per day, and vitamin C at 1,000 mg per day for her low cortisol. For her thyroid, she began a broad-spectrum mineral supplement that included copper 1 mg per day and zinc 20 mg per day, and she increased her vitamin A consumption by eating carrots and dandelion greens. She started a hiphop class, which I suspect raises cortisol, as found in a 2004 study of African dance published in Annals of Behavioral Medicine. Her biggest aha! moment came when she realized that it was the type of exercise that made a difference—she needed to exercise in a way that boosted her cortisol.

After six weeks, Jocelyn felt better but still had half of her symptoms. Her TSH was improved at 2.3 and her morning cortisol was 8, which is still below the optimal range. We added Step 2 of The Gottfried Protocol for her low cortisol, and she began taking licorice as a capsule twice per day. (Check with your doctor before taking licorice, as it may raise your blood pressure.)

Results: After another six weeks, Jocelyn’s symptoms resolved on the licorice, plus her TSH was normal at 1.3 and morning cortisol was normal at 12. Her blood pressure was normal at 110/75, which was more typical for her when she was feeling balanced. Jocelyn’s main “lever” was enduring stress with low cortisol, and the combination was impacting her thyroid function. When her cortisol was addressed through Step 2, and thyroid through Step 1, we corrected both imbalances without resorting to any prescription medications. This is not just my unique experience with reversible hypothyroidism caused by adrenal dysregulation, but a pattern documented by other clinicians.1

Jocelyn’s case suggests a few guidelines for multiple hormone imbalances. When more than one hormone is out of whack, things get more complicated, and I recommend additional resources to help guide you.

• Work with a trusted doctor. When more than one hormonal system is off, I suggest strongly that you find a collaborative doctor who has the time, knowledge, and interest to tackle your hormonal imbalances with you. If you feel you haven’t found the right match, see Appendix D for ideas and resources on how to choose a clinician who will be sensitive to your preferences, and won’t jump straight to prescriptions as the only option.

• Consider testing. When you have multiple hormone imbalances, blood or other testing (such as urine or saliva) reviewed with your trusted doctor is a good practice, since there is significant overlap between symptom groups. Hormones perpetually interact with one another, so measurement can be a helpful tool.

• Isolate the primary problem. Address the primary problem first. If you map your symptoms on a timeline, usually the primary hormone issue will be obvious as a root cause. This was clear with Jocelyn’s example: when her adrenal dysregulation was repaired, the thyroid problem resolved. As you may have learned in chapters 2 and 4, the glucocorticoids, most notably cortisol, are the main modulators—the alpha hormones—of the hypothalamus and pituitary, and these in turn control the feedback to the ovaries, thyroid, and adrenals.2 For most women, I look first to the glucocorticoids in any situation of multiple hormonal imbalances.

• Identify the antecedents, triggers, and mediators. In functional medicine, these factors are called the ATM. Typically, when you have a problem such as an overactive hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, you can trace it back to a predisposing factor, known as an antecedent. Here’s how one woman in my medical practice described her antecedent: “I was medically boring until age twenty-eight, when my mother was dying of cancer, and I took care of her for six months until she died. Within a year of her death, my periods stopped and I developed fibromyalgia.” Recall that fibromyalgia is related to low cortisol, and amenorrhea (when you experience three months without a period) can be caused by several problems—from a faulty control system of the ovaries (the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, which is how the brain controls the ovaries) to gluten allergy to premature menopause.

• Beware of the most common masqueraders. As you read in chapters 6 and 9, a broad range of chemicals known as endocrine disruptors often can affect more than one hormonal system—for instance, bisphenol-A acts as a xenoestrogen and a thyroid disruptor, and sadly, levels are detectable in the urine of 93 percent of American adults. Awareness of how chemicals in the environment can affect your hormones is essential.3

There’s a myriad of hormonal combinations that I identify in my office: high cortisol and low estrogen; low progesterone and low thyroid function; low cortisol and low thyroid; high cortisol, high insulin, and high androgens (plus high LH, low FSH, and PCOS, oh my!), to name a few. Here are the most common combinations that I see in my practice:

1. Dysregulated cortisol (high and/or low) and thyroid problem. Here I define dysregulated to mean that the body’s response to chronic stress is poorly modulated, or regulated, such that cortisol is not kept within an optimal range for the body and is either too high or too low, usually at different times within the same twenty-four-hour period.

2. Dysregulated cortisol and sex hormones

a. Estrogen (low)

b. Progesterone (low)

3. Low progesterone (estrogen dominance) and low thyroid hormone

Just as too many doughnuts, excess stress, environmental toxins, and sedentary living collectively lead to insulin resistance, where your cells become numb to insulin, there is growing support for the scientific basis for cortisol resistance, where your cells similarly become numb to cortisol.4 As you now know, cortisol is the alpha hormone, and other hormones such as thyroid, estrogen, and progesterone are submissive. When you do not manage optimally or follow healthy lifestyle design, several imbalances may occur at once, such as insulin and cortisol resistance.

Here’s the concept: perpetual stress raises blood cortisol levels. Our latest scientific understanding, however, is that the way cells react to cortisol—that is, whether the cells are sensitive (which is normal) or numb (which is not normal, and a sign of hormone imbalance, and in this case, hormone resistance)—may be more important than actual hormone levels in the blood.5 (This concept also suggests that questionnaires might be more helpful than blood tests for identifying cellular resistance, since we do not currently have a way to test for cortisol resistance.) As I mentioned, cortisol is one of the hormones known as glucocorticoids. We now have evidence that glucocorticoid receptor resistance (GCR) results from chronically high cortisol levels in the blood. That leads to low cortisol inside the cells of your body, which makes you feel as if you have the symptoms of low cortisol, despite your high blood levels. In other words, your glucocorticoid receptors for cortisol become unable to respond to cortisol. Using the lock-and-key analogy, your “lock” (glucocorticoid receptor) becomes jammed, and cortisol can no longer open the door. The final result is inflammation, which we learned is not good—it creates the bad neighborhood that tends to alienate the other happy hormones and neurotransmitters and makes you more susceptible to illnesses and disease, such as cancer and diabetes.

Several trials document this new theory of cortisol resistance.6 Persistent stress results in cortisol resistance, which makes you more likely to get sick with a cold and to produce more inflammation. Bottom line? Prevent cortisol resistance (and insulin resistance) by applying the health-promoting lifestyle design of The Gottfried Protocol.

In my practice, I’ve seen some distinct patterns when it comes to age and hormonal imbalances. Here’s what I’ve discovered:

Most often, the younger women who come to my integrative medicine practice have only a single hormonal problem, such as high cortisol, low progesterone, high estrogen, or high testosterone. These are the most common imbalances that I see and treat with The Gottfried Protocol. And although these younger patients come to me with symptoms, at this age the fix is often stunningly simple. Remember the theory that those of us who are aged thirty-five to fifty have the lowest psychological well-being of any age group? Before age thirty-five, there’s less stress and better resilience to meet it; there’s usually less hormonal upheaval from pregnancy; and there’s more organ reserve, longer telomeres, and a generally superior ability to roll with the punches. Women under the age of thirty-five are less likely to have multiple hits to their homeostasis, so it’s simpler to find the original cause for their hormonal problem.

Occasionally I see multiple hormonal issues in this age group. When I do, it’s most frequently women who have both cortisol problems and a thyroid issue, or high androgens together with wayward cortisol. I find that infertility is related to low progesterone, or sometimes low thyroid function. As women get closer to age thirty-five, the combination of the two hormonal imbalances appears more frequently. The most common hormone combination of this age group is dysregulated cortisol along with changes to thyroid, progesterone, or testosterone.

Why is this? Because cortisol is the most essential hormone that you make—you need it no matter what to deliver fuel to cells, which is the most basic task of a hormone in your body—and the nonessential sex hormones (progesterone, testosterone, thyroid) will be the first to get imbalanced when cortisol is the top priority. In other words, you will make cortisol, sometimes at very high levels, at the expense of your other hormones.

Women from thirty-five to fifty tend to have more than one problem at a time, probably because of the chain reaction of ovarian aging and chronic stress. In fact, how you age is profoundly influenced by how you navigate stress.7 Sometimes we can identify the primary issue and correct that first. Then, as a result, the secondary hormonal imbalances can be addressed and cleared up. But sometimes you have to address more than one hormonal problem at a time and treat them simultaneously for best results.

That’s when the concept of Charlie’s Angels becomes increasingly important—you want the entire team of estrogen, thyroid, and cortisol working for you, not against you. You always want to first address the root cause, particularly when you have more than one hormonal issue. And all roads, not surprisingly, usually lead back to the limbic system, amygdala hijack, and the adrenal glands.

In other words, adrenal function is the first place to look when you have multiple symptoms of hormonal imbalance, which is due to hormonal intercommunication—that is, there are classic patterns of hormonal and neurotransmitter consequences. When you’re stressed at twenty-five, you go to a yoga class, sleep it off, or call a good friend or maybe even your mother. When you’re forty-five, chronic and repetitive stress cranks up your cortisol until your adrenals can’t make enough, then your thyroid slows down and your joints get cranky, and as a result, your knee may hurt too much to go to yoga. When you’re stressed, your thyroid abruptly slows down production of the key thyroid hormones—and you feel cold and achy and your hair falls out. Then you develop extreme PMS because high cortisol from stress blocks your progesterone receptors, and perhaps you develop progesterone resistance. You rage and may want a divorce. Next month, because your ovaries are semiretired, you don’t ovulate and then your estrogen is low. Serotonin levels fall, and because serotonin (Nature’s Prozac) manages sleep, appetite, and mood, you become an insomniac, which worsens your depression and ramps up your appetite. You get the idea.

In other words, one imbalance (chronic stress and wayward cortisol—initially high, and then low) begets a cascading crescendo of hormonal problems. Dysregulated cortisol is linked to thyropause, low progesterone, and eventually, as you get closer to menopause, low estrogen.

Keep in mind that the key differentiator for ages thirty-five to fifty is that the ovaries are sputtering and this makes many women feel like they are under siege: one day you want another child and feel blissed out, and the next day you want to run away from home to become a forest dweller. As I described in chapter 2, the boss of your Charlie’s Angels—your adrenals, ovaries, and thyroid—is in the brain, the hypothalamus. In other words, the hypothalamus is your Charlie. If your hypothalamus ain’t happy, Mama ain’t happy. You want the boss, your hypothalamus, to be your ally since it controls the orchestra of your hormonal symphony, and the symphony can get extremely out of tune starting sometime between age thirty-five and forty-five.

Your hypothalamus tells its neighbor, the pituitary, to make more or less of the control hormones for your adrenals, ovaries, and thyroid. Several important factors determine how much hormone your endocrine glands should make, including how much stress you perceive, changes in weight, light/dark cycles (especially how much light you are exposed to at night), quantity and quality of sleep, and medications (such as birth control pills), to name a few.

Unlike women under age fifty, who demonstrate lower psychological well-being (probably because they are focused on being all things to all people and trying to appear as if they have it all together), your hormones quiet down again after fifty. Some women rather enjoy getting their crone on. Those hideous (and sometimes hilarious) dark corners of perimenopause are behind them. Women past menopause often no longer feel a need to endure the sacrifices and occasional masochism of selfless service. Have you noticed that women after fifty are more stress resilient, and seem to have more choices and actions to express their authentic needs and values? That’s not just anecdote—it’s well documented.8

Stress diminishes during this time after childrearing and prime career-building years, and this translates into a calmer neuroendocrine system so the chain reactions don’t take hold. You come more fully into your own, and learn not to give a damn about other people’s opinions of you. Yes, there’s the unforgiving metabolism to contend with, but at least you are of relatively sound mind as you check your thyroid, take on a Paleo diet (see page 174), and make time for yoga. There’s more sanity and choice.

You get down to business. You can no longer put off the important stuff that you postponed while you were busy tending a family and career or running a household. There’s a planet to save, some other underdog that needs your voice, or a garden to water.

Even with less stress among women over fifty, there might be more cortisol resistance. We know that certain biomarkers change after age fifty: cortisol rises, DHEA and other androgens decrease, and thyroid autoimmunity increases to a peak at ten years after menopause.9 More women are diagnosed with insomnia, probably related to increased cortisol, and as a consequence, they experience more disrupted sleep and lower melatonin levels. And that can make you feel lousy and foggy brained the next day.

Here’s one woman’s experience over her hormonal arc from her thirties through her sixties:

When I was in my thirties, I never had any clue that the stress of an adrenaline-fueled job and a difficult marriage had an impact on my hormones, and on my inability to conceive and to carry a fetus to term.

When I hit my forties, I found myself in a pressure cooker of a job just as I was—totally unknowingly—about to go through perimenopause. I had three teenagers. Juggle-R-Us. I did a very good job of leaving my emotional self at the door before I went to work, but my body rebelled. I began to suffer from migraines. I never lost a day of work because of migraines, but some days I had to prop up a cardboard likeness of myself at my desk and just soldier on. My periods became heavy, when they had normally been quite manageable—and so painful that I was awakened at night (great for a hard day’s work and a long commute). It was as though my emotions spent every day at the amusement park, on the roller coaster. Finally my doctor prescribed a low dose of birth control pills, which smoothed over my emotional life, but did nothing for my migraines (in fact, it probably exacerbated them).

In my fifties, as my periods became more erratic and I lumbered on toward menopause, the first sign that something was terribly amiss was my inability to sleep. My doctor tinkered with hormones, to little avail. Finally she suggested I try an acupuncturist at the college where she was studying. Yeah, right, someone’s going to stick me with needles and I’m going to be able to think again? It took a few months, but between weekly sessions of acupuncture and a daily dose of Chinese herbs, I was able to sleep well enough that my brain worked.

Charlotte, whom you met previously, in chapter 4, articulates the interconnection of stress and her other hormonal symptoms, including infertility, migraines, unstable emotions, and sleep problems.

As you read through my explanation of the common hormonal imbalances I see in my practice, you might notice that most of them have one feature in common: dysregulated cortisol. This is no coincidence. Women respond to excess stress in a predictable manner. Left unchecked, unremitting stress has important consequences—including infertility, a “fried” control system (the hypothalamus), fatigue, and moodiness—for women who are largely neglected by mainstream medicine. Your organ reserve gets depleted along with your natal chi, according to Traditional Chinese Medicine, and your telomeres may shorten. You age prematurely, and so do your ovaries (diminished ovarian reserve) and thyroid (thyropause).

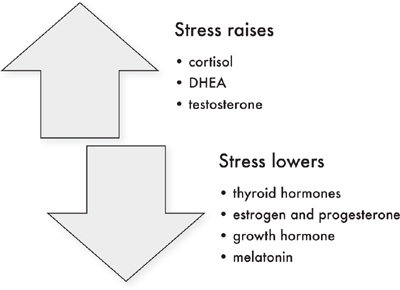

Let me repeat: cortisol bosses around production of several major and minor hormones. Cortisol regulates blood sugar, immune function, and blood pressure, plus it inhibits or stimulates many other hormones. When stress is excessive or perceived to be excessive, initially cortisol (a member of the glucocorticoid family) rises in the blood, saliva, and urine. This is accompanied by increased androgens, including DHEA and testosterone. High cortisol blocks or lowers the production of thyroid hormones, sex hormones (such as estrogen and progesterone), growth hormone, and melatonin. Ultimately, high cortisol impacts the glucocorticoid receptor, leading to glucocorticoid resistance (GCR). Over time, if the adrenals can no longer continue the high output, cortisol levels will decrease.

Figure 7. Effect of Stress on Hormones.

One of my husband’s Stanford friends, Chip Conley, wrote a brilliant best-selling book, Emotional Equations, about emotions and the mathmatical formulas that describe them.10 His simple formulas describe complex yet universal truths about emotions and triggered the idea that I could similarly describe hormonal combinations in the form of equations. I’ve included several hormonal formulas in this chapter to help you understand the interactions among the variables, which are hormones and actions that affect hormones, such as physiological stress. Here’s one applicable to adults to get us started:

![]()

This simple equation shows that stress goes up when your adrenals are off kilter and make too much cortisol. Stress levels go down with restorative sleep, regular exercise, nutrient-dense food, and contemplative practice, such as meditation.

Referring back to the questionnaires in chapter 1, if you answered “yes” to three or more of the questions as in either Part A or Part B (or collectively, more than three in both Part A and Part B), plus three or more in another part, you have a problem with the cross talk between the adrenal glands and either the thyroid or the ovaries. Allow me to explain.

Here’s the typical scenario. Your local doctor diagnoses a slow thyroid. Relief! Finally, you’ve got an explanation for the crushing fatigue, poor mood, lack of libido, and climbing weight—you’re not going crazy. It’s biology, not an invitation to search for neuroses. You begin taking medication, usually a synthetic T4 such as Synthroid or levothyroxine as a tablet by mouth. You feel like a million bucks the first few days and weight starts to fall off. You’ve discovered the holy grail. Then, BAM! After a few more days or a couple of weeks, you’re tired again. Your weight climbs. The honeymoon is over. You’re desperately seeking a course correction.

There are many women who are properly prescribed thyroid hormone and do not experience the party-crashing adrenal on their thyroid honeymoon. But if your symptoms are atypical, or you feel better but then backslide, or if you answered “yes” to three or more questions in chapter 1, Part A and/or Part B and Part G, I suggest you take into account the important chain reaction between the thyroid and adrenal systems, because an adrenal problem will cause your thyroid issue to be much worse and harder to correct, and vice versa.

Your thyroid reacts to stress and high blood levels of cortisol by slowing down production of thyroid hormones. High adrenaline, the short-acting neurotransmitter that rises in response to stress, is linked to lower thyroxine (T4), which results in high thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and symptoms of a sluggish thyroid. Cortisol, when it is deficient or excessively high for prolonged periods of time, can slow down thyroid function.11

We know that the amygdala, the part of the limbic system that perceives stress, contains high numbers of thyroid receptors and type 2 deiodinase, which mediate thyroid hormone production.12 When your stress is high, and your body is flooded with glucocorticoids such as cortisol, this slows down the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis and thyroid hormone production, and thyroid hormone has a similar effect on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.13 That is, when the amount of glucocorticoids (the fancy term, as you know, for the hormone cortisol and its cousins) in your body goes up, the amount of thyroid hormones produced goes down, and vice versa. Folks with dysregulated cortisol and thyroid problems document this finding, showing that both high and low cortisol can impair thyroid function, although the relationship is not linear.14

Both extremes of cortisol can drag down your thyroid. Women who have too much or too little cortisol, plus an underperforming thyroid, get a double dose of fatigue, yet often neither condition is typically recognized in conventional medicine nor believed to be properly documented by existing biomarkers.15 Yet fatigue and burnout remain epidemic in our culture. Not surprisingly, 78 percent of women report fatigue.16

Another way to interpret the interdependence of stress and limbic hijack, together with thyroid function, is to consider the relationship between thyroid and cortisol as nonlinear—and parabolic—which means when cortisol is too high or too low, you make less thyroid hormone. When cortisol is just right, and in the normal range, the thyroid performs best and generates optimal levels of hormones.

I recommend that you put into place The Gottfried Protocols from both chapters 4 and 9. Start with Step 1 for both chapters. Reassess your symptoms six to twelve weeks after you’ve implemented the changes of Step 1. If you are still not feeling that your hormone issues are improved, add in Step 2 from both chapters. If you still are experiencing five or more symptoms from both chapters 4 and 9, see your doctor to consider further testing and a prescription for bioidentical hormones. Keep in mind that your thyroid medication requires adequate cortisol to work best: not too high and not too low.

High cortisol is the single most common hormonal problem I see in my practice, and high cortisol with low estrogen and/or progesterone is another common combination. This varies by age: low progesterone coupled with high cortisol is the most common hormone combination that I see in women younger than thirty-five years of age. If you answered “yes” to three or more of the questions in chapter 1, Part A and/or Part B (the high and low cortisol questionnaires), together with three or more from Part C, Part D, and Part E, this is your hormone combo. Among women over age forty-five, I more commonly see cortisol either high or low together with low estrogens. If you answered “yes” to three or more of the questions in chapter 1, Part A and/or Part B together with Part E, adrenal dysregulation combined with low estrogen is your issue.

Low sex hormones are inextricably linked to the prevalence of stress in the lives of modern women, and we know that the stress begins early. Tests show that 91 percent of female college students feel overwhelmed, far higher than the rate in men, even though it is documented that psychological well-being doesn’t bottom out until age thirty-five.17 Additionally, college women have higher rates of exhaustion than men (87 versus 73 percent) and more anxiety (56 versus 40 percent in men); and prescriptions for sleeping pills have tripled among college students since 1998.18

After college, we’ve got the usual suspects that raise cortisol: caffeine, sleep deprivation, and certain genotypes related to the important brain fertilizer called brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF, which keeps your brain young, agile, and able to learn, or to be neuroplastic)—not to mention low estrogen, eating disorders, birth control pills, and the stress of working and commuting.19 Many of these factors either cause or are associated with low progesterone. For instance, when you lose weight from disordered eating or take a birth control pill, you block ovulation and this lowers your progesterone.

Honestly, we all just need more protection from stress, from our wiring to overprovide, and from our tendency toward perfectionism. If you’re like me, you need a meditation coach to show up about once per hour to remind you to breathe deeply. While on the subject, I’d love for this coach to help me with detachment parenting and perhaps a reminder to laugh, and to develop an affinity for the simple things, at least until I hit fifty and stop seeking to meet the needs of others full time.

As I mentioned in chapters 2 and 4, your adrenals and ovaries work together in an intricate dance. Estrogens and progesterone are made in both your adrenals and your ovaries, but will be shunted toward the production of more cortisol when a woman is under chronic stress, as shown in Figure 2 of chapter 2. As a result, chronic stress leads to high cortisol levels and lower progesterone levels. You also will be lower in other sex hormones, such as estrogen, testosterone, and DHEA, but let’s focus first on progesterone.

High cortisol will lower production of both estrogen and progesterone. When stress is long-standing, your body will try to balance the neuroendocrine system by making less estradiol because of Pregnenolone Steal. In women younger than forty, infertility may occur because the combination of amygdala hijack—where you overreact to the normal, daily stressors—and high cortisol makes your ovaries slow down and not ovulate. The balance of ovarian hormones is delicate, and amygdala hijack can take the ovaries offline. During perimenopause, high cortisol and low estrogen worsen symptoms of hot flashes, night sweats, and mood swings. After menopause, low estrogen is depressed further by high cortisol, and may worsen bone loss and cause osteoporosis.

The goal in this situation is to calm the overactivated brain. Apply Step 1 of The Gottfried Protocol from chapters 4 and 7 simultaneously. If symptoms of high cortisol and low estrogen persist, then add in Step 2 from each chapter. Most women are able to regain balance with Steps 1 and 2, but if not, apply Step 3 from each chapter. Women who are treated with estrogen will temporarily lower their cortisol levels, but I recommend normalizing cortisol first before resorting to estrogen therapy because of the significant risks.

In addition to Pregnenolone Steal, high stress will force high cortisol to block progesterone receptors so that you feel low in progesterone on a cellular level, even if blood levels are normal.

Let’s take PMS, linked to low progesterone and chronic stress for some women. PMS is a collection of emotional, physical, and behavioral symptoms that affects 40 to 60 percent of women of reproductive age.20 The cause is not known, but appears to be a multifaceted mash-up of genetics and neuroendocrine vulnerability. Some, but not all, women with PMS have low progesterone.

When it comes to PMS, here is the formula that synthesizes the variables.

PMS = Cortisol/Progesterone

When stress is high, cortisol rises and PMS worsens. When progesterone is low, PMS also worsens. In other words, there’s a dance between cortisol and progesterone in the development of PMS, and you want to address both adrenal function and your production of cortisol as well as your progesterone to minimize PMS.

I encourage you to begin Step 1 of The Gottfried Protocol from both chapters 4 and 5. Retake the questionnaires for both chapters after you’ve implemented all or most of the recommendations in Step 1 for six or more weeks. Remember that it takes at least this amount of time to reach hormonal homeostasis. After your test period, if you still have more than three symptoms from the questionnaire of one or both chapters, add the recommended strategies from Step 2 for each chapter for another six weeks. If after six weeks of Step 2, symptoms persist, move to Step 3 of each chapter.

As you learned in chapter 5, low progesterone is common beginning around age thirty-five and often leads to symptoms of estrogen dominance, whereby too much estrogen is produced relative to progesterone. When this happens, your Lady Justice is not holding the scales in balance, as nature intended. There is some evidence that low progesterone and low thyroid function may be connected.

From chapter 5, you know that the most common reason for low progesterone is aging ovaries. As a woman’s ovaries get older, ovulation is less regular, and this lowers your progesterone level.

Here is the evidence that links estrogen dominance, low progesterone, and low thyroid function.

• Subclinical hypothyroidism is associated with a short luteal phase (the second half of your menstrual cycle) and insufficient progesterone.21

• Progesterone regulates the expression of thyroid receptors in the uterus.22

• Too much estrogen may increase thyroid-binding globulin proteins—meaning that thyroid hormone is more bound and is less available to receptors inside cells—which may lower thyroid hormones and cause symptoms of thyroid insufficiency.

• Hypothyroidism can decrease progesterone receptor sensitivity in animal studies, and perhaps cause “progesterone resistance.”23 (See chapter 5 for more details.)

• Among adolescent girls, selenium and progesterone in the luteal phase have the greatest influence on thyroid function.24

By now you know that there is a common theme: that stress plays a key role in hormone imbalance. Note that there is a reciprocal relationship between stress and fertility, which can be expressed as follows:

Fertility = (progesterone*thyroid hormone)/stress

Apply Step 1 of chapters 5 and 9 for six weeks, then retake the questionnaire. If three or more of the symptoms from either category persist, then apply Step 2 from each chapter for six weeks. If symptoms continue, move to Step 3 from each chapter for either or both category.

This chapter has provided a sampler of the intricate interconnections between a woman’s lived experience and hormonal biochemistry, which often manifest as multiple hormonal dysfunctions. Myriad factors come together and coalesce into a unique hormonal milieu, depending on your body and degree of stress. These factors include your lifestyle, including how you eat, supplement, and move; your genetics and how lifestyle changes the expression of your DNA code; your environmental toxin exposures; and your immunity and infections (both old infections, such as the mononucleosis virus, and current ones).

Awareness is the first step. If you think you have multiple imbalances, take a deep breath. You are on the way to getting the help you deserve, on multiple fronts. If you start to feel overwhelmed, remember: sometimes small shifts can make a large difference for multiple hormonal imbalances, and correcting the problem is easier than living with the consequences. And remember the Pareto Principle: 80 percent of the change comes from 20 percent of the effort.