Your film heritage is a language no less evolved and subtle than the mother tongue you use to communicate verbally. Knowing its evolution through film history prepares you to make films that audiences find striking.

A good general information website for technology and film history is Greatest Film Milestones in Film History at AMC’s Filmsite, www.filmsite.org/milestones.html. The roots of documentary film lie in two nineteenth-century inventions: photography and sound recording. First came still photography, developing steadily from the 1830s onward (Figure 3-1). It was the first instance of preserving moments in time, and people thought it miraculous. Encountering his first Daguerreotype photograph, a French painter of the day exclaimed, “From today painting is dead.”1 Of course he was wrong. Painters simply had to rethink painting—a radical reconsideration that many artists have to face. Edison’s first sound recordings in 1877 also struck people as revolutionary, something you can sense from listening to the first scratchy talking and singing preserved from so long ago.

The first movies in the 1890s were silent and used static camera angles to make single-shot movies of daily life, or staged short improvised scenes (Figure 3-2). Gratified by the reactions of their audiences, the makers learned by experiment what techniques worked best for domestic cameos, newsreel events, or magic shows. In the decades that followed, they developed a host of new tools—cameras, faster film stocks, synchronous sound, and editing equipment—so that film’s language, and its ability to move hearts and minds, all developed fast. Because the audience’s grasp of screen conventions was in evolution too, filmmakers found they could use an increasingly sophisticated narrative shorthand.

You can see most of the growth in cinema language that fuels today’s screen eloquence from little more than a dozen chosen documentaries. Very little technique has been outmoded or superseded: almost every advance in screen language, almost every technical and ethical issue remains vibrantly alive today (Table 3-1).

In the text that follows, key films or film anthologies are in bold print. With each groundbreaking film I have tried to pair an example that uses the same film language in a modern context. You can view passages from nearly all the films cited by entering their titles and director’s surname in YouTube (www.YouTube.com). Beware “personalized” versions in which someone has mashed up (re-edited) the original. Often you can find interviews with notable directors on the Internet, or films about them. Since some of my own history and that of my family exists as threads in this century-long tapestry, I have taken the liberty of mentioning them. Cinema is a living art spun from intertwined human lives.

FIGURE 3-2

1904 holiday-makers at Blackpool Victoria Pier in The Electric Edwardians.

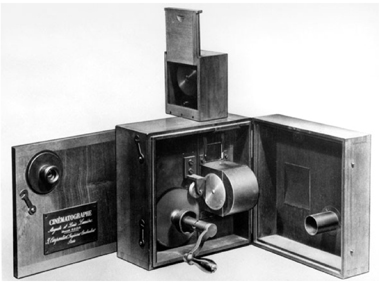

In 1895 the brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière (Figure 3-3) laid the foundations of the cinema in France. During a business trip to New York, their painter and photographer father, who owned a photographic business in Lyon, saw Edison’s Kinetoscope (Figure 3-4). He saw a moving image in a box, and thought his sons were inventive enough to get the image up onto a public screen. They fulfilled their dad’s expectations by borrowing the intermittent action of the sewing-machine to fashion a hand-cranked camera of wood and brass (Figure 3-5). They filmed nonfiction scenes from the daily lives of those around them and began showing 50- second movies. By ingeniously coupling it to a light source they made their camera double as a projector and contact printer.

FIGURE 3-3

Auguste and Louis Lumière. (Courtesy of Institut Lumière.)

By mounting the camera on a tripod and letting the action pass in and out of the frame, their filming technique came direct from still photography. The Lumière Brothers’ First Films (France, 1896–98, DVD remastered from the originals) shows their work as fresh as in its infancy. The Lumière employees go to lunch in ’Workers Leaving the Factory and in Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (1896, Figure 3-6) we see an everyday scene at a station in which the descending passengers glance at the camera, oblivious that they are making history. Each little narrative lasts the entire run of the camera, is structured around an observed or contrived event, and the brothers have no idea yet of making camera movements or cuts. Participants usually know they are being filmed; in Feeding the Baby (1895) Auguste and Marguerite Lumière enjoy showing off their daughter Andree, and the family gardener becomes the victim of a hosepipe prank in The Sprinkler Sprinkled (France,1895). Plainly he enjoys hamming it up for his employers’ camera.

These simple and extraordinarily beautiful works are the world’s first home movies. Notice that film is always now and in the present. The invention of film brought a new tense to international language, one you might call the present eternal. True, Train Arriving took place over a century ago, but we are right there with those passengers alighting on the platform each time the film plays.

Soon Lumière operators swarmed across the world shooting exotic or newsworthy events, and their films founded a new money-making show called the cinema. Somebody broke company policy by taking a moving shot from a Venetian gondola, and others soon followed by shooting tracking shots from carriages, automobiles, and trains. The race to develop film language was on. Visit the Lumière Museum online at www.institut-lumière.org and see a range of early cinema gadgets at www.victorian-cinema.net/machines.htm.

Early footage is still turning up. In the 1990s someone clearing a French sanatorium attic found a biscuit tin containing two unknown Lumière films. They had lain there for a century after a show given for inmates. In England, workmen demolishing a factory found barrels containing 28 hours of wonderful footage from the early 1900s. The Electric Edwardians—The Lost Films of Mitchell & Kenyon (GB, 2005, Figure 3-7) shows the work of two photographers filming busy street scenes in the north of England. They developed their footage and invited paying customers to see themselves on the screen the same night. Perhaps my great-uncle Sidney Bird, a cinema projectionist in Portsmouth in 1909, projected material like this. Go to YouTube and see tradesmen jogging past in horse-drawn carts, and others idling in the street, mugging at the camera, or running errands by bike. The Mitchell and Kenyon footage contains some of the earliest shots of someone directing staged footage (Figure 3-8).

FIGURE 3-5

The Lumière Brothers’ hand-cranked camera. (Photo courtesy of Institut Lumière.)

FIGURE 3-7

Mineworkers and their families outside a colliery seeing a movie camera for the first time in the BFI’s The Electric Edwardians.

Between 1895 and 1920 cinema audiences saw great quantities of reality footage, particularly that representing the vast, unfolding tragedy of World War I. In spite of so much actuality in the cinemas, it was not until Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North (USA, 1922, Figure 3-9) that audiences saw a nonfiction narrative with a deliberately imposed thematic meaning. Flaherty was an American mining engineer who had spent his boyhood prospecting with his father in northern Canada. There he had learned to love and respect the Inuit people. In 1915, using an early 16mm camera, he began an ethnographic record of an Eskimo family. Editing his film back in Toronto, he discovered that nitrate film stock and chain-smoking make dangerous bedfellows, for his 30,000 feet of negative went up in flames, and he was lucky to escape alive. Afterwards, seeking funding to reshoot, he was compelled to screen his surviving workprint repeatedly. This convinced him that his film was flat and pedestrian, and so he resolved to shoot another that would tell more of a story.

Setting out again with his hand-cranked camera and slow film stock that often needed artificial light, he began shooting in appalling weather conditions. Often he would ask his subjects to do their actions in special ways for the camera. Flaherty’s Inuit cast were keen to demonstrate an old way of life, and by now his central character Nanook (not his real name) really liked Flaherty. The two felt they were putting on record a vanishing culture, and would watch dailies (uncut material) together. Thus Flaherty came to shoot a factual film in real surroundings, but acted like a fictional story (Figure 3-10). His shooting style is basic even by the standards of his day, but his cast is delightful and the Arctic majestically beautiful. His participants (as I shall call those who take part in documentaries) came to know and trust him so well that they seem free of all self-consciousness.

FIGURE 3-10

While they act as though in a fictional story, the participants in Nanook collaborate to make the film as authentic as possible.

To us the film seems ethnographically authentic, but Nanook’s clothing and equipment actually come from his grandfather’s time. You can’t see it, but the igloo has no roof (to allow in light for filming) and the hunting spears are antiques because the Inuit were already using rifles. Flaherty was in fact reconstructing a way of life already swept aside by industrial society and its technologies. Audiences did not know it, but Nanook, shown cheerfully biting a phonograph record after hearing it play, was no ignorant native. He was Flaherty’s astute collaborator who transported and assembled their filming equipment, and developed their footage ready for screenings.

Generations of critics have argued over the ethics of Flaherty’s artifice, but what lifts Nanook of the North above the level of complaint is its noble vision of an Eskimo family surviving in the hostile Arctic. Not only does it respect its subjects, but it builds a larger theme—that of humankind’s ancient and deadly struggle for life against the forces of Nature. Flaherty shows a traditional Eskimo family as a tightly interdependent unit whose very survival depends on everyone carrying out assigned functions. Nanook as their leader is a human dynamo; during their increas-ingly isolated and perilous journey he improvises housing with irrepressible humor. He hunts food, teaches his children, and uses his ingenuity to tackle each new obstacle. The flame of life, the film implies, depends on resourcefulness, cooperation, and endurance. Most tellingly, Flaherty does not return the family to safety at the end of the film, but leaves them huddled in the Arctic wastes with a snowstorm engulfing their long-suffering huskies. Then, while New York audiences lined up around the block to see the film, its subject died hungry and in obscurity—perhaps at home from disease, or perhaps as a result of a hunting acci-dent. Who can imagine a sadder or more ironic validation of the underlying truth in Flaherty’s vision? (Figure 3-11).

Flaherty’s hybrid. melding of truth and fiction in the service of a higher purpose did not die with him. It is alive and well this century in The Story of the Weeping Camel (Germany, 2003, Figure 3-12) directed by two Munich film students, Luigi Falorni and Byambasuren Davaa. In collaboration with Mongolians living in yurts in the Gobi Desert, the directors have made a partly scripted, partly improvised film about Mongolian family life. It centers on the annual birth of the bactrian camels on which their lives have traditionally depended.

Very little in documentary history has gone out of date or been abandoned. Every approach and technique still has its modern application.

The word “documentary” surfaced during a mid-1920s conversation between Flaherty and John Grierson, a Scottish social scientist interested in the psychology of propaganda. Commenting on a cut of Flaherty’s fiction film Moana (USA, 1926), Grierson said he thought it was “documentary” in intention. And so, retrospectively, was Nanook— today acknowledged as the nonfiction genre’s seminal work.

FIGURE 3-12

The Story of the Weeping Camel, a modern tale from the Gobi Desert that is directly in the Flaherty tradition. (Photo courtesy of the Kobal Collection.)

FIGURE 3-14

Going a step farther with poetic and emotive performance, Flaherty wrote Tabu in 1931 for F. W. Murnau.

Laurels never came easily to Flaherty, who came under attack for creating lyrical archetypes. This is undeniably true, for Flaherty was a romantic who never forgot his wilderness boyhood. Several of his films even use a boy as their central character. Though his detractors admired his humanism and poetic photography, they thought it deplorable that he assembled his own photogenic families instead of filming authentic ones. In Man of Aran (USA, 1934, Figure 3-13) he further incensed his critics by leaving out the large house of the Aran islanders’ absentee landlord, the individual mostly responsible for the islanders’ deprivations. It was the Aran Islanders’ ancestral struggle with Nature that excited Flaherty, not their abuse by an extortionate social system.2

The charges leveled at Flaherty’s romanticism and the resulting volley of questions about the basis for documentary still reverberate today: What is documentary truth? How objective is the camera? Can you ever be objective like a social scientist? Must one show literal truth or can it be the spirit of the truth? And whose truth should you show? When you juxtapose material to imply new meanings, what makes your edited version more truthful or less so? When can you use poetic and emotive means, as Flaherty does, to evoke feeling? And what part does aesthetics play in persuading an audience? Flaherty went a step farther and in collaboration with F. W. Murnau helped initiate a thoroughly spurious fiction film (Tabu—a Story of the South Seas, USA, 1931) set in Tahiti (Figure 3-14).

After the 1917 Russian Revolution, the Bolshevik government found itself administering a vast federation of nations whose least educated citizens could neither read nor understand each other’s languages. Among those working for the revolution by compiling newsreels for the Agitprop regional train screenings was the poet, musician, and film editor Dziga Vertov. Seeing how powerfully affected audiences were by imaginative camerawork and editing, he developed his Kino-Eye manifesto—meant to be a prescription for recording life without imposing on it.

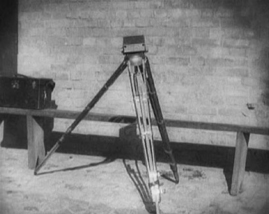

FIGURE 3-16

The tripod taking a mock bow in Man with the Movie Camera.

Vertov’s silent masterpiece Man with the Movie Camera (USSR, 1929, Figure 3-15) is a visual symphony. It begins in a movie theatre and dashes into the streets to spin many strands of simultaneous narrative—in homes, in the streets among the homeless, in workshops and factories, on the beach—all making up a tumultuous day among the citizens of Moscow and Odessa. The film works virtually without titles, and revels in showing its ubiquitous cameraman mounted on flying trucks, clambering up bridges, or standing astride towering buildings. Vertov includes every form of trick-photography in the film’s gallery of playful illusions, and at the end, with its virtuoso performance complete, the camera takes a mock bow on animated, striding tripod legs (Figure 3-16).

The DVD of Man with the Movie Camera (significantly enriched by Michael Nyman’s obsessive, minimalist score) divides the film into chapters with titles that suggest how ambitiously Vertov has seized the medium: Awakening, Locomotion, Assemblage, Life Goes On, Manual Labor, Recreation, Relaxation, and Cinematic “I” (a play on “Kino-Eye”).

With brilliant foresight, Vertov extols film’s unending possibilities by making the camera almost humanly aware of its own magic vision. That is, by juxtaposing so much action and so many points of view, Vertov believed he had freed the screen from all viewpoints except that of the all-seeing camera. In reality it is Vertov’s mind and personality that deliver what we see. In a virtuoso experiment, he demonstrates how each action, movement, and shot has its own inherent rhythms. From the film’s form and content, so creatively edited even though editing machines did not yet exist, we see music for the eye. Today’s equivalent is MTV and music videos.

Man with the Movie Camera demonstrates one of the medium’s most important capacities— that it can alter our perception of time and space. Notice how its opening shots compress the lacing of a film projector down to a few short, indicative shots. Ordinarily this is quite a lengthy, fiddly process, but Vertov shows a hand mounting a film spool, and then a hand making the first moves to thread the film path. This convention, called Ellipsis, is like shorthand since it allows just a few actions to imply a much longer process, a technique universally used today to abridge time and space.

In its first quarter-century the cinema developed a richly expressive language of action, movement, and imagery. Silent film, accompanied by live music, stimulated the audience’s imagination by telling stories and developing ideas visually. In the 1920s, electrically driven cameras freed the operators to use both hands, and become even more mobile and inventive.

Sadly, the cinema’s tidal wave of visual creativity lost impetus when synchronous sound arrived in the late 1920s. The cinema, including documentary, fell into the grip of a theatrical discourse that relied on narration, music, and sound effects. This was because of the sheer bulk and power requirements of sound equipment, which confined shooting to film studios. I first saw a sound camera (as they were called) in the late 1940s as a nine-year-old making a day visit with my dad, a make-up man at England’s Pinewood Studios. He led me off the blindingly bright Technicolor stage to step into the gloom of a darkened truck parked nearby. There sat the Westrex behemoth that recorded sound photographically on to 35mm film. Its unlucky operator sat distant from the hubbub of the set, permanently wearing headphones and awaiting instructions.

A year earlier my father, a recently demobilized sailor, had somehow talked his way into becoming a make-up trainee for David Lean’s classic Dickens adaptation, Oliver Twist (GB, 1948). His first assignment was to put an ominous black patch over the eye of Bill Sykes’ white bull-terrier. One evening at home he tried to get me to play the moment when Oliver faces the orphanage overseers and holds up his bowl, saying “Please sir, can I have some more?” (Figure 3-17). Living as I did in a rural village, and having seen no drama of any kind, I was mystified by what he asked of me. Long after his death I realized he must have been reliving the orphanage youth of which he never spoke.

Narrated travelogue became common in the 1930s, and in Land without Bread (Spain, 1932) Luis Bunuel satirizes the genre. As the renegade son of a privileged Spanish family, Bunuel implies that the medieval poverty and suffering he finds in a remote region of Spain results from criminal neglect by his own caste. The ragged, stunted, and inbred villagers that we see know nothing about the water-borne illnesses that are killing them, and Bunuel makes us incredulous that church, state, and landlord could remain indifferent to the human souls in their care.

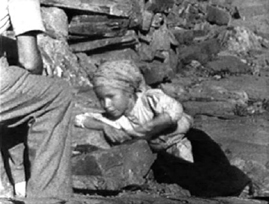

Using a grandiloquent symphony as musical accompaniment, the film’s flat gaze at its catalogue of horrors drives even a modern audience to outrage. By nature, Bunuel is a satirist. He purposely makes us angry by showing a surreally awful situation using the pseudo-scientific cant of the travelogue. Like Flaherty, he was not above rigging the evidence—if you look carefully at the death of the goat when it falls from a ravine, you’ll see a tell-tale puff of gun-smoke. Everything else, however, seems authentic enough. One of the crew even steps into the frame to help a sick child that died the next day (Figure 3-18). The dead baby floating down a stream in her little coffin as the grieving family makes its way to the graveyard is an indelibly tragic image.

The documentary could seldom afford sync sound in a studio, and anyway its subject matter was supposed to be real life captured as it happened. So its makers continued to shoot silent, the editor creating a sound track afterwards from music, effects, and narration (Figure 3-19).

FIGURE 3-18

Poverty, sickness, and death in Land without Bread because of a ruling caste’s indifference.

Harry Watt and Basil Wright’s Night Mail (Great Britain, 1936, Figure 3-20), made by John Grierson’s General Post Office film unit, features a crack postal team sorting letters on an express train for delivery next morning in Edinburgh. The bucolic vision of fields, cows, rabbits, and ancient churches evokes an interlude of tranquility between two grimy industrial heartlands. What you see are metaphors for a society in flux— wealth and poverty, industrial cityscape and rural countryside, night and day, past and present. Through orchestrating the beat of words, images, repetitive work, and the rhythmic beat of the train wheels, the film creates a driving sense of forward movement. Key to this are two important elements: Benjamin Britten’s score and W. H. Auden’s striding narration:

This is the Night Mail crossing the border, Bringing the check and the postal order,

Letters for the rich, letters for the poor,

The shop at the corner and the girl next door…

The brief sync dialogue exchanges in Night Mail were probably post-synchronized, that is, spoken lines were post-recorded and lip-synced to simulate live dialogue. To accommodate the large 35mm camera, the letter-sorting and dialogue sequences had to be shot in a set with a removable wall. Thus the postmen you see are re-enacting their daily work in a replica sorting carriage that is being rocked by stage-hands to simulate the train’s movement.

FIGURE 3-20

Mail sorters re-enacting their work on a set for Night Mail. (Photo courtesy of the Kobal Collection/GPO Film Unit.)

The film generates tension because the postmen are working against the clock to complete their tasks before the journey’s end. Helping this are charged scenes of the high-speed mailbag drops and pick-ups along the line. The film’s temporal spine comes from its subject—an epic journey from the smoky metropolis that takes us up through rural England’s backbone and arrives just as the sun rises over Edinburgh, its citizens still snoozing in their beds:

And shall wake soon and long for letters,

And none will hear the postman’s knock Without a quickening of the heart,

For who can bear to feel himself forgotten?

The commentary that started out with a quick, sharp, repetitive beat, now ends on a slower, loping beat as the train majestically slows for its arrival. Night Mail shows what is possible with a stirring subject, great photography and narration, and first-rate music. It also shows that film is music. Incidentally, film industry lore says that no film involving train travel has ever failed.

Color film was expensive and came late to documentary. Alain Resnais’ Night and Fog (1955, France, Figure 3-21) integrates black-and-white with color, and might be the most haunting documentary ever made. In 31 nightmarish minutes the film visits what remained of the World War II Auschwitz extermination camp, and projects us headlong into the terrified daily existence of the prisoner. What, it asks, lies beneath the brackish water in the ponds, now that it’s all over? Much of the film’s power comes from its restrained and evocative narration by the French poet Jean Cayrol, himself a death camp survivor. Another powerful element is the astringent strings and woodwinds in the atonal score of Hanns Eisler, an Austrian wounded in World War I.

Playing against stereotype, the film never dramatizes or heightens. Instead its questioning narration is spoken in a dry, neutral monotone, while the score counterpoints delicate, playful woodwind themes or spins out high, trilling violin cascades against archival footage of casual horror. Here every mute object speaks, and the film ends by asking: Who among us will step forward next time, ready to torture and kill in exchange for a little power?

Night and Fog is a pinnacle in documentary filmmaking, and after many a screening my classes would sit in shattered silence. Its non-sync shooting, coupled with brilliant writing, composing, and editing shows that a screen essay can deliver a huge impact. Today, this eloquent technique is very little used.

FIGURE 3-21

Resnais’ impassioned plea for humane watchfulness in Night and Fog. (Films Inc.)

Two of my earliest editing assignments—one concerning international marriage customs, the other, the 1966 soccer World Cup—were shot and cut in this way. It was laborious but satisfying work, because you created an audio composition of narration, music, and sound effects. The highly original films of the photographer, traveler, and filmmaker Chris Marker, such as Le Mystere Koumiko (France, 1965) and Sans Soleil (France, 1983, Figure 3-22), make him one of the cinema’s truly original essayists, whose preoccupations include the fleeting and unstable nature of memory. Anyone who has seen his short, enigmatic sci-fi photomontage La Jetée (France, 1962, Figure 3-23) has had an unforgettable cinema experience, though not one that can be called documentary.

FIGURE 3-22

Sans Soleil, directed by the essayist, traveler, and thinker Chris Marker.

FIGURE 3-23

In Marker’s La Jetée, love is a lost memory from a previous life.

Halfway through the twentieth century, new technologies began to make the film unit light and mobile. First came magnetic tape recording in the 1950s, which allowed sound shooting with a portable audio recorder. The industry favorite was the ultra reliable battery-powered Nagra, which held a steady speed even as its operator broke into a run (Figure 3-24). Faster film stocks allowed cameras to shoot by almost any available light, and 16mm cameras were evolving. The Eclair NPR, with its quiet mechanical movement, low-profile coaxial film magazines, and virtually instant magazine changes, sat comfortably on the operator’s shoulder and revolutionized camera design (Figure 3-25). Filmmakers now had the tools to capture actuality as it happened, and this completely transformed every aspect of location filming, from newsgathering and documentary to fiction film. In the documentary, event-driven or character-driven stories practically replaced scripted and narrated subject-driven ones.

FIGURE 3-24

Portable sync sound from the 1960s onward, thanks to the Nagra III. (Photo courtesy of Nagra, a Kudelski Group Company.)

Documentary influenced fiction filmmaking, and I was fortunate to work on Tony Richardson’s A Taste of Honey (1962, GB, Figure 3-26), shot almost wholly by available light on location. Documentary cameraman Walter Lassally’s portrait of sooty, post-industrial Manchester—a city of canals and decaying industrial might—was simply thrilling. The script, about a pregnant working class girl abandoned by her mother, came from the autobiographical play by Shelagh Delaney. Richardson came from the experimental theatre but had participated in the Free Cinema Movement, a loose grouping of London residents from several countries who made short, ground-breaking documentaries about British working-class life. Their work sharply challenged the stuffy institutional documentaries and mediocre, studio-dominated feature films of the day, where my cinema life began. Richardson’s preference for working fast and informally, and his actor-centered directing, brought a new but short-lived vibrancy to British cinema.

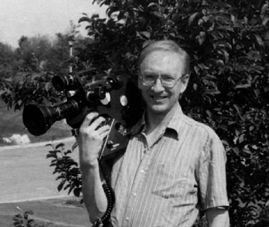

FIGURE 3-25

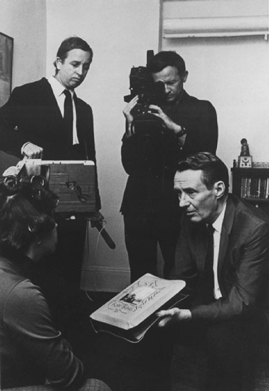

The revolutionary Eclair NPR wielded by the author. (Photo courtesy of Aran Patinkin.)

FIGURE 3-26

Tony Richardson’s A Taste of Honey. a fiction film benefiting from the expertise of documentary cameraman Walter Lassally.

The new immediacy generated opposing philosophies about the proper relationship between the documentary camera and its human subjects. The central question was this: Is truth on the screen something you find, or is it something you participate in and help to make?

Prominent American and Canadian documentarians of the time favored transparent filmmaking, in which participants seemed to live their lives unaware of the camera. Robert Drew, Richard Leacock, D. A. Pennebaker, Fred Wiseman, Allan King, and others favored what they called direct cinema (now called observational cinema). Like ethnographic filmmakers, they shot unobtrusively and by available light, aiming to capture the spontaneity and uninhibited flow of events as people were living them. In the late 1960s the intrepid Albert and David Maysles and their editor Charlotte Zwerin made the landmark docu-mentary Salesman (1968, USA, Figure 3-27). The brothers had taught themselves filmmaking and even cobbled their own equipment together. Their amazing film follows a sales drive by hardnosed bible salesmen—really a pack of hunters goaded on by corporately generated sales quotas. To complete each sale, a salesman must gain entry, befriend the householder, give a demon-stration, and then make a killing by securing a signed order. We see them use all manner of per-suasion, but their customers live pitifully narrow, cramped lives and don’t need, and can’t afford, lavishly illustrated bibles.

Here is the pinched lower middle-class world that Arthur Miller wrote about in his classic play Death of a Salesman. The central character is Willy Loman, a salesman based on Miller’s own father who is degenerating from exhaustion, misplaced optimism, and worry over supporting his family. In the Maysles Brothers’ documentary, Paul is the kindest and funniest of the salesmen, and cannot bring himself to extort the likeable, struggling homebodies from whom they try to extract orders. Like Miller, the Maysles brothers have put a frame around the man whose kind heart and active conscience doom him to fail in a system of corporate exploitation. No two works expose the cost of the American dream with more deadly wit and accuracy.

FIGURE 3-27

The Maysles Brothers’ 1968 landmark documentary Salesman exposes the struggle for survival among door to door salesmen.

Europeans favored the participatory approach to filming documentary, which at the time was called cinéma vérité. This approach seeks truth by treating any significant activity, in front of the camera or behind it, as proper subject matter for the documentary record. The idea came from the French ethnographer Jean Rouch who had found, while documenting life in Africa, that filming invariably provoked important off-camera relationships with participants. These he felt should become part of the film record and so he included them in his ethnographic films. In Chronicle of a Summer (France, 1961, Figure 3-28), working with his sociologist co-director Edgar Morin and their Canadian cinematographer Michel Brault, Rouch asked ordinary Parisians the deceptively simple question: “Are you happy?” It releases a torrent of touchingly personal and confessional responses. These the unit filmed as a free interaction between themselves, the crew, and participants. Some people, shown their own replies later on the screen, wanted to extend the dialogue—which Rouch and Morin filmed and included. As a gesture to Vertov, they called their method cinema verite, since “cinema truth” is a translation of his kino-pravda. Afterwards the term cinema verite degenerated into a catch-all for spontaneous filming of any kind, so participatory cinema is the term used today.

FIGURE 3-28

In Chronicle of a Summer Jean Rouch and his team asked ordinary Parisians the deceptively simple question: “Are you happy?”

By acknowledging documentary as a collaboration with participants, rather than an objective observation of them, the directors of participatory cinema could now catalyze or even provoke events, and probe for truth rather than simply await its appearance. Rouch particularly prized the “privileged moments” when a human truth emerges plainly and miraculously like an egg from a chicken.

An excellent participatory film is Ira Wohl’s Best Boy (USA, 1979, Figure 3-29), in which a New York family faces a gathering crisis. Pearl and Max are aging, and love their 52-year-old mentally handicapped son Philly so much that they can’t let him go. Wohl sets out to film his lovable cousin, and while time remains, presses his uncle and aunt to consider letting Philly move into an appropriate institution. We see Philly being tested by a psychologist, many scenes of him at home doing chores for his mother, and Philly singing “If I were a rich man” from Fiddler on the Roof. Max dies, worn out after an operation, and leaves his wife Pearl bereft. How, she asks, can she ever let go of her “best boy” now? But relinquish him she must, and Philly begins to flourish among challenging responsibilities in a residential home. Pearl, always so open, talks with heartbreaking candor about how very alone she now feels. We realize that this is the price she must pay for her son’s autonomy. The family was very aware of the filming, but the camera’s presence seems to bring out the best in everyone, not least because the director cares so deeply for them. The DVD contains a follow-up film with the ever-cheerful Philly, now aged 70.

Best Boy shows that you must often keep the camera running when shooting people under duress, and just wait. People need time to process anything that is emotionally taxing, and impatient filmmakers blow such moments by chivvying their subjects onward. Wohl (who went on to become a psychotherapist) is always willing to linger for truth to unfold, and when great tension leads to a major sense of release, his patience is amply rewarded. This barometric rise and fall of pressure is called the dramatic arc or dramatic curve. Characteristically it builds, intensifies, peaks at a crisis point, and then releases (Figure 3-30). To direct well, you will need to develop sharp instincts for how this works—in life as in drama—so we shall give documentary’s dramatic components closer attention in the next chapter.

Some claimed a certain truth and transparency for the “fly on the wall” observational documentary, but unless the camera is actually hidden—ethically dubious at best—participants know it’s there and adjust accordingly. In fact, every form of observation produces some change in a human situation, whether it’s a child visiting a family playing a game of cards, or a crew shooting discreetly at a distance. An observational film may make us feel like privileged observers, but we are seldom seeing life unmediated as such films imply. They appear so because an editor has subtracted everything that would break the illusion, such as people turning to the camera, or visibly adopting special behavior.

For a recent “fly on the wall” observational documentary, see Yoav Shamir’s Checkpoint (Israel, 2003, Figure 3-31). It is the director’s first film, and records without comment what happens at Israel Defense Force (IDF) checkpoints, where Shamir himself once served as a guard. The state of Israel exists because of the atrocities of the Holocaust, which in 1948 impelled Zionists to carve the country out from territory long settled by Palestinian Arabs. Today it is a small, embattled region in which dispossessed Palestinians must constantly pass checkpoints. Some youthful IDF guards carry out their policing function with tolerance and even humor, while others do not. It is always demeaning for the indigenous Palestinians to wait in line—sometimes for hours—to attend a nearby hospital, or to get to their workplace. The IDF scrutinizes every pedestrian, car, truck, bus, and ambulance because each at some time has been a conduit for bombs that killed and maimed Israelis.

FIGURE 3-31

Yoav Shamir’s Checkpoint is a recent “fly on the wall” observational documentary.

Some of the uniformed, gun-toting 19-year-olds “follow orders” with sadistic disregard. Plainly they enjoy subjecting Palestinians to senseless aggravation. Every story Palestinians tell them is suspect, no matter how credible and evident the reason for needing to cross. The cases get worse as the film proceeds, and you feel a growing hopelessness and outrage. The film uses no commentary or interior monologues: its points emerge simply from faces, behavior, body language, and by the way it lingers for minutes on some dignified older man trying in vain to get his sick wife to a medical appointment. You feel a deepening rage and frustration on behalf of the humiliated—which is what this Israeli film wants you to feel. How tragic, you tell yourself, that the scrutiny meant to protect a nation is worsening the conditions that threaten that country’s very existence. This is a message the film doesn’t ever need to put into words: it gathers like a thunder cloud.

Checkpoint’s structure is a series of repeating cycles, each worse than the last. The whole business feels like the advancing screw-thread in a torture device. Ironically, the IDF has since adopted the film as training for its guards in what not to do.

The documentary historian Eric Barnouw neatly summarizes the differences between these two major documentary philosophies:

The direct cinema documentarist took his camera to a situation of tension and waited hopefully for a crisis; the Rouch version of cinema verite tried to precipitate one. The direct cinema artist aspired to invisibility; the Rouch cinema verite artist was often an avowed participant. The direct cinema artist played the role of uninvolved bystander; the cinema verite artist espoused that of provocateur.3

To reveal human truth on the screen, documentary-makers of either persuasion must make subjective judgments. The differences between them pale to insignificance when you realize that both depend on editing to abridge, shape, and intensify what is diffused by time and space in real life. Both approaches prize the unpredictably spontaneous and telling moment, and both reject the essentially theatrical process of scripting and re-enactment. Since both need story structure to hold the viewer’s attention, both share much with the fiction film.

You need declare no allegiance in your filmmaking to either approach: today’s documentaries are eclectic and use whatever approach best serves the needs of the evolving subject matter. Science, nature, or historical documentaries that rely on archive footage or on re-enactment still need scripting, and being able to write a film narration is still a key skill that you should develop, since one day you will need it.

Both documentary approaches had similar drawbacks: they used high film shooting ratios (meaning a high amount of footage shot compared with that used) and they were uncertain of outcome. In trying to fashion a gripping narrative from a mass of captured action, editors took on a new burden, and rose to the challenge by inventing new forms of allusion and abbreviation, or ellipsis. Building on the legacy of Dziga Vertov, they found freer and more intuitive ways of counterpointing voice and effects tracks, and used impressionistic, even hallucinatory cutting to abridge time and space. In due course these innovations became an accepted part of feature film language.

With longer documentaries fashioned out of ever-larger bodies of source material, editors had to create dramatic structures able to sustain an audience through a feature-length film. And so the three-act dramatic structure, first identified in Greek drama several hundred years BC, begins to appear in the documentary as it had long done in fiction cinema. The three-act form is simply a way of classifying the phases of an unfolding story:

| Act I | Establishes the setup (establishes characters, relationships, and situation and dominant problem faced by the central character or characters). |

| Act II | Escalates the complications in relationships as the central character struggles with the obstacles that prevent him/her solving the main problem. |

| Act III | Intensifies the situation to a point of climax or confrontation, when the central character then resolves it, often in a climactic way that is emotionally satisfying. A resolution isn’t necessarily a happy ending: it might be an ageing boxer accepting defeat—sad, but inevitable. |

| The Maysles brothers’ Salesman (1968) indeed breaks into the classic three-act structure: | |

| Act I | (Boston, snow) is the exposition that introduces the salesmen and their work, shows their working class origins, and delineates their “problem” (having to hunt for sales to stay alive) |

| Act II | (Chicago, packed conference hall) is the corporate sales conference that escalates their “problem.” Publishing moguls announce their goals, pressures, and values, and put the group on notice. Stragglers, they say menacingly, will be eliminated for “refusing success.” |

| Act III | (Florida, heat) is the extended race for survival during which Paul, the most likeable of the bunch, inexorably falls behind until he confronts defeat and becomes tacitly ostracized. This leaves us conflicted: Paul has failed at predation, has been rejected by his colleagues, and is now suffering. Somehow he will have to reinvent himself elsewhere—a quintessentially American predicament. Will he find a more amenable and constructive way to make a living, or is this all he knows? |

Later in Chapter 18: Dramatic Development, Time, and Story Structure we shall see how prevalent this three-act structure is, and how useful it can be to your directing as you seek to predict the actions and rhythms at work in everyday life.

In the 1970s, reel to reel video recording promised a cheaper and more flexible process. At first it was of poor quality and clumsy to edit, but the advent of cassettes and small format video improved the situation. Compared with editing film, tape-to-tape editing was deathly slow because every editing change required a follow-up ripple of changes throughout the tape. Once nonlinear (computerized) editing arrived in the late 1980s, documentarians began moving gratefully toward the promised land. Digital cameras and computer software handed them the kind of freedoms writers had got from word-processing.

Today with a home computer we can edit, create text and titles, freeze, slow-motion, or reverse our footage, as well as make color and contrast changes. We can not only weave together sound and picture but also apply the full range of contemporary image manipulation. This unshackles the screen from the banality of real time and pictorial realism, and allows us to use a narrative language that is more subjective and impressionistic.

From the 1980s onward, documentary-makers moved toward mixed documentary forms and drew more freely on allied art forms and disciplines. Here are some examples to give a flavor of the genre as it moves toward its second century.

Michael Apted’s 28 Up (GB, 1986) is the most famous episode in a series of longitudinal study films, the first shot in the early 1960s. At seven-year intervals ever since, Apted has stepped away from directing feature films to revisit the same fourteen English individuals (Figure 3-32). Begun as 7 Up when they were seven-year-olds, the series has now reached 56 Up, with each film drawing upon an ever-growing bank of earlier material. We have the unique privilege of watching them grow from kids through tremulous young adulthood, and on into middle-age. Composed mainly of sensitive, probing interviews, the Up series shows both individual stories and the dynamic of groups. The series premise (ruling idea) is that family and social class implant profound expectations that are both positive and negative in their consequences, which children go on to realize in their subsequent lives. In chilling support of this, 7 Up quotes the Jesuit saying, “Give me a child until he is seven, and I will show you the man.” At first it comes largely true, and in 28 Up the most disturbing portrait is of Neil, who blames his home life for making him wind up as a solitary vagabond, plagued with psychological disturbances. For his sake alone you will want to see the rest of the series. Accompanying the DVD for 49 Up is an illuminating interview with Apted, who seems gloomily resigned to continuing the series until he keels over. Some participants are equally weary of putting their lives on record, but everyone seems to recognize that the series is the most embracing account ever made of people growing up and wrestling with their destinies.

FIGURE 3-32

Every seven years Michael Apted steps away from his feature career to shoot another Up episode. (Photo courtesy of The Kobal Collection.)

Structurally an Up film is like an octopus, each arm a single story, and all joined to the common body of a recorded past. The commanding determinants of class and race persist, but half a century later we see that the suffocating original premise has fractured under the pressure people feel to make life-saving adjustments. Sure, family advantages and disadvantages are alarmingly evident in children’s self-image and expectations, but most participants alter their trajectories in maturity, often with startling and hopeful results (Figure 3-33).

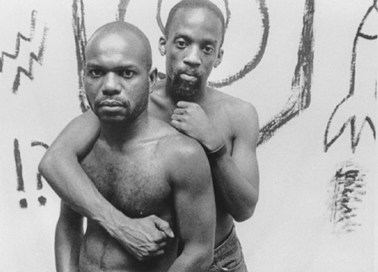

Through a series of imaginative, elliptical, and disturbingly urgent tellings and performances, Marlon T. Riggs’ Tongues Untied (USA, 1989, Figure 3-34) conveys what he and others, black and gay like himself, experienced while growing up in a majority white, racist, and homophobic society. A journalist and poet, Riggs has produced a performance art film like Brechtian theatre. Sidestepping all recognizable traditions it hurls us from a finger-popping rap performance to the anguish of losing friends to AIDS; from a sad drag-queen telling of her loneliness, to stories of gay-bashing and of a white gay club that refused a black gay man entry on the grounds of his color. From archives come civil rights marchers and Eddie Murphy telling a homophobic joke.

Called performative in style, there is no through-line of argument or assertion, only a volley of forcefully stylish performances—everything from dance and body movement to inner monologue, street talk, and rap. Structuring the film’s kaleidoscopic form is a driving, insistent sense of rhythm, as though Riggs is angrily drumming out the remains of his foreshortened life. Because the film received some national arts funding, it caused apoplexy among conservatives over the use of taxpayers’ money. Riggs died of AIDS, and sadly the film is his last testament.

FIGURE 3-33

Some Up participants maintain their trajectories in maturity, others go off at a creative tangent in this long and most fascinating of documentary sagas. (Frame from 7 Up.)

FIGURE 3-34

Marlon Riggs and Essex Hemphill defiantly face the camera in Tongues Untied. (Photo courtesy of Signifyin’ Works/Frameline.)

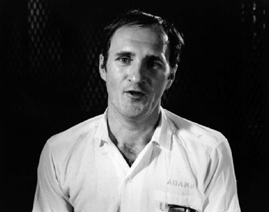

Errol Morris’ The Thin Blue Line (USA, 1989, Figure 3-35), though built traditionally on a foundation of interviews, makes imaginative use of music, re-enactment, and clips from old detective movies. Creating its own trial structure, the film examines the course of Texas justice on behalf of a man who may be falsely imprisoned. Its hypnotic Philip Glass score helps fuse an opiate mix of fact and fiction that gradually undermines the probity of the original trial. The crux of the discussion is contradictory evidence concerning what happened during 30 seconds one night on a Dallas freeway. A police car stopped someone driving on the freeway without lights, and as the cop walked over to tell him to turn on his lights, the car’s occupant shot him. Who did the shooting? The film repeatedly re-enacts the encounter, but with key differences according to each witness’s account. Morris uses the lawyers, passers-by, drawling Texas policemen, as well as the two men in the car, to subvert each witness’s version. With its central characters on death row, and so much of its action taking place at night, Morris jokingly classified his film as a documentary noir.

His rock-steady visual style, minimalist score, and obsessive re-examination of key details eventually pays off by eliciting new evidence that points to the actual murderer. Because of Morris’ film, Randall Adams not only escaped execution but was released from prison. See the masterly opening on YouTube, which lays out the Adams’ feelings about being a hostage to destiny.

Agnes Varda, who directed the diary/essay documentary The Gleaners and I (France, 2000, Figure 3-36), is an experienced fiction director whose late husband Jacques Demy was France’s most imaginative maker of musicals. Varda’s documentary, beginning from the throb of string quartet music and nineteenth-century paintings of gleaners in cornfields, develops the theme of picking up and using what others have thrown away—a green habit by which she has furnished her cosy home. Armed with a small handicam she journeys to different regions of France in search of junk and more junk. Along the way, she meets a rich array of characters gleaning for food, art materials, or, as some relate with passion, simply out of ecological principle. Like a road movie the film goes from one encounter to the next. Varda makes what she films into state-of-mind representations so that we see her vanished childhood, her love for Jacques, and that she too will be discarded—by life itself. Her journey in this tender, good-natured film becomes metaphysical, so that denotation becomes connotation. By the end, this highly circular autobiography conveys a rare sense of intimacy.

FIGURE 3-35

Randall Dale Adams, convicted for a murder he did not commit, in Errol Morris’ “documentary noir” The Thin Blue Line. (Photo courtesy of The Kobal Collection/American Playhouse/Channel 4 Films.)

FIGURE 3-36

Agnes Varda, director of the intimate documentary journal The Gleaners and I. (Photo courtesy of The Kobal Collection/Stéphane Fefer.)

In Sicko (USA, 2007, Figure 3-37) Michael Moore produces a damning satire on American business methods. The film trains its cross-hairs on the US health system where it exposes an appalling litany of failure. At the time, 50 million men, women, and children had no medical coverage, and privatized insurance was excluding anyone with a “pre-existing condition” (now, who doesn’t have one of those?). Moore builds a series of surreal comparisons of other countries’ health systems that make you guffaw in disbelief. After exposing the denial of healthcare to 9/11 first-responders sick from their heroic rescue efforts, Moore loads them into a boat and cruises to Guantanamo Bay in Cuba. Calling up through a megaphone at some scary-looking US Army fortifications, he asks if his patients might get some of the free medical care available to the “evildoers” imprisoned within. The reply, a warning siren blast, sends Moore scuttling off to Havana with his sad cargo. There they get free medical care, since Cubans, it seems, have better health and life statistics than Americans, and all for a fraction of the cost.

As always, Moore combines ambush journalism, hilarious satire, and leftist sympathy for the ordinary working stiff. His films’ preferred form is the Everyman quest, for which he dresses in his signature baseball hat and baggy tee shirt (Figure 3-38). His first-person narration starts from a central question, and then proceeds to alternate between reasonable question and astonished discovery. Simple disbelief propels him from one anomaly to the next until, and like some latterday Candide, he can only acknowledge that the American health system is not the best of all possible worlds. Moore sees healthcare in America as a theatre of the absurd. Using stunts that juxtapose victims and perpetrators, he projects an appalling vision of how the profit motive distorts what elsewhere is a basic human right.

FIGURE 3-37

Just a regular guy—Michael Moore in Sicko asking a few simple questions. (Photo courtesy of The Kobal Collection/Dog Eat Dog Films/Weinstein Company.)

The San Francisco experimental filmmaker Jay Rosenblatt often plucks his archetypal homemaker moms, pipe-smoking businessman dads, and rigid, emotionally beleaguered kids from a trove of mid-twentieth-century “informational” films that he found on a dump. He makes them represent the suffocating roles his family endured while he was growing up. In Phantom Limb (USA, 2005, Figure 3-39) Rosenblatt uses interviews and a range of found materials to fashion a 12-chapter confrontation with a domestic tragedy—his own and his family’s unexpressed guilt and anguish following the death of his younger brother. Rosenblatt’s work, and this film in particular, often feels like the strangled inner scream of a generation marching in lockstep with the received wisdom of its time. Seeing his body of work, however, you see a vital rebalancing taking place. In I Used to Be a Filmmaker (USA, 2003, Figure 3-40) Rosenblatt celebrates filmmaking and fatherhood, clearly the two great salvations in his emotional life.

FIGURE 3-39

Jay Rosenblatt behind his ill-fated brother Eliot in Phantom Limb. (Frame from their father’s 8mm film, courtesy of the filmmaker.)

Archive footage is a staple for History Channel and Discovery Channel productions, which specialize in expositions of historical and scientific matter. A fine combination of testimony and archives underpins Ken Burns and Lynn Novick’s impassioned series for PBS, The War (USA, 2007). There World War II participants do what battlefield veterans seldom do, that is, speak about the atrocious suffering they inflicted or witnessed, and about the resulting pain they will carry to their graves. Equally good is The Central Park Five (USA, 2012) directed by Ken Burns, Sarah Burns, and David McMahon. It reveals what the five New York black teenagers suffered when falsely indicted for raping and half-murdering the young woman known as the Central Park jogger. Based on interviews, archives, and contemporary footage, the film makes imaginative use of surreal montage techniques which convey the nightmare of being alone and powerless in the coils of a justice system convinced you must be guilty. Harried into making false confessions (“so you can go home”) prior to their trials by cynical police, the five got long prison sentences in response to a media frenzy and a public eager to blame poor, black youths.

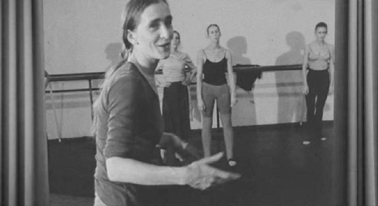

Two films that amply repay the somewhat unnerving assault of 3D on the viewer are Werner Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams (France, 2010, Figure 3-41) and Wim Wenders’ Pina (Germany, 2011). Both subjects use the new technology justifiably, since each has a particular need for the third dimension. Herzog’s treatment of man’s earliest known artworks in a cave near Chauvet in Southern France shows how the artists of 32,000 years ago integrated the rock-face undulations in their depictions of animals. Though the film was a box-office success, it left Herzog uninspired about using 3D again.

Wenders’ film is about the late modern-dance choreographer Pina Bausch, whose Wuppertal company perform her most acclaimed works. Of all artforms treated by the screen, dance has always seemed to suffer worst, so the addition of depth makes a critical difference. The film however is really about Pina herself who, rather than drill her company to a standard, took a personal and supportive interest in developing each of her dancers in their own way. She then drew on what each could uniquely contribute, notably in her dances about male–female relationship. Thus the film is about the wise leadership of an unegotistic, enlightened creator, remembered by her dancers with great love (Figure 3-42).

FIGURE 3-42

Wim Wenders’ Pina, which uses 3D to make dance happen in space on the screen.

Rather like the 1958 William Burroughs novel Naked Lunch that came looseleaf in a box for the reader to arrange, the interactive documentary makes a set of documentary resources available on the Internet for the postmodern viewer to explore at will. The writer and interactivity authority Sandra Gaudenzi (www.interactivedocumentary.net) divides the interactive documentary into four modes—the hypertext, the conversational, the participatory, and the experiential.4 Unlike traditional media that “hardwires” documentary materials into a unique structure that blurs their separate identities, hypermedia keeps the elements and structure separated, leaving users free to create their own relationships and meaning from source materials. The interactive movement’s search is for a commendable openness that permits “the participator to enter in the creative process” and thus have greater agency. Not since Gutenberg introduced moveable-type printing have people felt such excitement about exchanging ideas and knowledge, so the influence of the Internet, of offering open access to (someone’s choice of) documentary materials, holds unknown potential. Meanwhile, those who know what’s best for us are racing to invent better censorship, so democratic choice may become moot anyway.

Quite separately, I wrote a keynote article for the Australian film journal Lumina5 about the Arab Spring rebellions, and the action that followed Middle East social media users viewing and exchanging what were essentially documentary materials. Their governments had been unable to suppress the exchange of opinions, experiences, essays, cartoons, jokes, reality footage of all kinds, underground political writings, historical parallels, and whatever else. Yet social media users, without necessarily making or seeing special documentaries, had ingested source materials and concluded they must protest their regimes. I speculated action came from a collective-unconscious conclusion made from years of having internalized documentary forms and arguments. Probably it will take decades to unravel what really happened.

Interactive literature did not catch on with the public, and interactive documentary may not either, unless made into an artfully structured game, which weakens the cause of free exploration. Most prefer the more tainted process of watching a narrative and pondering the construct of relationship between cause and effect. Perhaps we best find our own way through encountering the propositions and interpretations of others. Through the very ancient medium of stories we resonate to different sensibilities and worldviews, identify our affinities and antipathies, and decide who and what we must push against. It is a viable but unscientific way of being curious. Maybe the interactive documentary will change documentary as web forms have changed so much else.

Why not make an analysis of a few minutes in a favorite documentary of yours using AP-1 Making a Split-Page Script ? Also known as TV script format, you use it to lay out images and action in the left-hand column, and the corresponding words and sound against them in the right-hand. Its merit is that it allows an exact transcription of the relationship between words, music, sound effects, and imagery, which is often highly revealing, and something you cannot precisely appreciate in a viewing. The split-page script-form also makes an excellent planning medium if you intend to make, say, a historical film involving archival footage and voice-over. Another form of film you could try is the diary form, using the SP-14 Diary Film project. You could make use of family video footage and still photos, and record your inner thoughts and feelings at the time, or now in retrospect, as voice-over.

1. Paul Delaroche, circa 1839.

2. Included with the DVD of Man of Aran is George Stoney and Jim Brown’s How the Myth Was Made (1978) which returns to Aran and investigates Flaherty’s processes with some of the film’s surviving cast.

3. Documentary: A History of the Non-Fiction Film (Oxford University Press, 1974), pp. 254–55.

4. See Sandra Gaudenzi, “The Interactive Documentary as a Living Documentary” at the documentary website Doc Online, www.doc.ubi.pt, an especially rich source to those who can read Spanish and Portuguese.

5. Rabiger, “Synaptic Documentary,” Lumina, July 2011, Australian Film and Television School.