Documentaries are stories that aim to change our hearts and minds by organizing their characters, situations, and pressures toward a revelatory purpose. They mean to expand our knowledge and alter our emotional frame of reference.

This chapter looks at the relationship between the chronology of documented events, their organization into a satisfying dramatic form, and the way in which a story’s dramatic needs may require reorganizing a story’s events for maximum impact.

The filmmaker and philosopher Michael Roemer suggests intriguingly that plot in fiction is really about the rules of the universe at work, and that the most absorbing characters are those who contest—heroically, and often unsuccessfully—the way things are.1 This holds true for documentary, since a central character refusing to accept his fate can be either funny or tragic. Some contest the status quo set by society and win; others are unable to accept the workings of a much darker fate. Josh Oppenheimer’s Act of Killing (Denmark/UK/Norway, 2012, Figure 18-1) deals with an intractable kind of human cruelty—by those sponsored by the authorities to wreak unimaginable brutality on those protesting their grip on power. That “might makes right” or that the ends justify the means is one of the ugliest among human delusions, and its grip on rulers is virtually universal. Anyone who follows world news sees the cost in blood, torture, and death everywhere.

Why do we so often think of central characters in documentary as people to whom things happen? Maybe, being the hero of our own story, we notice how people act on us, but not how we act on others. Is this a survival mechanism, or a mindset left over from the vulnerability of childhood?

Ingrained passivity when directing documentaries will blind you to all the ways that participants fashion their own destiny and make you keep seeing victims. Surely this is why so many documentaries enshrine the “tradition of the victim.”2 There is something dangerously patronizing about this. How you think of your central character largely determines what reaches the screen.

What makes a hero, and do they mainly exist because we have need of them? The archetypal hero is one writ large, a character of magnitude who faces outsize challenges. This was hardly Rosa Parks, who in 1955 challenged the status quo in the South by refusing to yield her bus seat to a white person. Her action of refusal was a timely symbolism that helped precipitate the American civil rights movement. In the late 1960s I filmed World War I conscientious objectors who had faced imprisonment, torture, and execution for refusing to put on uniform and kill men like themselves. At first they were “cowards,” but soldiers returning broken from the obscenity of trench warfare said they too would have been “conchies,” had they known what war was really about. So which are the heroes?

The dramatic tension a film generates from such situations comes from getting us involved with people and their issues, and making us care that they prevail. In a way, delineating such people is easy because their accomplishments are so tangible. How do you involve us with someone less extraordinary?

Apply this to anyone you know well to see how closely character and destiny are related. Use this when making a character-driven film to see how much your subject has forged their own destiny. Simply revealing this can often make a very satisfying biographical film, especially as ordinary lives often have something heroic about them—the spouse who cares selflessly for a partner whose Alzheimer’s disease prevents the sufferer from even recognizing the carer.

Effective stories nearly always have a central character who develops because of their struggles. In Steve James’s Hoop Dreams (USA, 1994, Figure 18-2) the two black basketball players William Gates and Arthur Agee grow up, but their development is disillusioning because they find they are just pawns in a system. The development in Grizzly Man (USA, 2005) is particularly ghastly since the special relationship Timothy Treadwell imagined he had with bears was a prescription for death. Philippe Petit’s heart-stopping high wire walk between the ill-fated World Trade Center towers in James Marsh’s Man on Wire (UK, 2008, Figure 18-3) successfully demonstrates Petit’s extreme skills and courage, and although he does not change, it is enough to see him survive.

FIGURE 18-3

Philippe Petit walking between the doomed World Trade Center buildings in Man on Wire.

In the history of literature, some writers reacted with such nausea to the moral exhortation implicit in “good” characters that they invented the antihero. Fielding’s Tom Jones, Thackeray’s Becky Sharp, and Camus’s Meursault are all stigmatized, humanly flawed characters trying to make their mark as they negotiate an amoral world. In documentary, the confused, petty criminal who is the title character in Stevie (USA, 2002) is also an antihero. When he was a troubled child in a dysfunctional family, the director Steve James had been his “Advocate Big Brother,” and is now returning to his small town roots to find out where Stevie is now (Figure 18-4). The young man’s problems have only grown, and he is in trouble with the law. By the end of the film, Stevie goes to prison for sexually molesting an eight-year-old relative. A heinous crime, certainly, yet the film makes one compassionate toward him. Failed on all sides, he is never less than pitiably human, and this leaves James wondering whether he might have done more.

Whatever the antihero may be, he or she is not a victim. Too much television ennobles victims or glorifies those who overcome horrific injuries “against all the odds.” It seems cynically facile to “celebrate the human spirit” of some poor young man rendered legless and impotent. Lured into the military on the promise of going to college, he goes instead into combat—something his political masters assiduously avoid when it comes to their own offspring.

As protagonists, antiheroes are complex, contradictory, and hostile to convention. Often their special qualities emerge in unexpected ways as they negotiate the hand dealt by fate. Some important questions:

● What do you want your audience to make of your central figures?

● What are you trying to say through them?

● What do you want to say about human nature, folly, vulnerability, or aspiration?

Analyze a few dramatic plots—fiction or nonfiction—and you soon find common denominators in their organization. To explain this, the ancient Greeks devised the three-act structure, touched upon earlier in Chapter 3: Documentary History in relation to the Maysles Brothers’ Salesman (USA, 1961, Figure 18-5). The three-act structure is still an invaluable tool for understanding and organizing story elements. See it not as a formulaic strait-jacket, but as an aid to the clarity of your thinking as a dramatist. To recapitulate:

| Act I | Establishes the setup (establishes characters, relationships, and situation and dominant problem faced by the central character or characters). |

| Act II | Escalates the complications as the central character struggles with the obstacles that prevent him/her solving his main problem. |

| Act III | Intensifies the situation to a point of climax or confrontation, at which point the situation is resolved, often by the central character and in a climactic way that is emotionally satisfying. A resolution doesn’t necessarily have to be happy: it might be an ageing boxer accepting defeat—sad, but inevitable. |

This archetypal organization of a story is probably rooted in the way early humans narrated their hunting journeys and battles with rival tribes. Without lighting, they must have spent much time in winter recalling stories around a f re, and narrative form as we know it must have evolved from the way they evolved storytelling for the best audience response.

The three-act structure is plainly visible in a “reality” survival type of program, Pioneer Quest: A Year in the Real West (Canada, 2003). A group sets out to discover what life was like on the prairie for pioneers. Winter is coming and they must race to build a shelter. They work through all the obstacles that made hand-building a cabin from local materials slow and diff cult, and the resolution is a viable (if draughty) cabin, in which the volunteer “immigrants” struggle to keep warm during the coldest winter for 120 years.

By trying to imagine our ancestors’ lives, “how would I manage as a prairie settler?” is a central type of question. It is especially poignant if you realize how little you really know about your own parents’ lives, because you never thought to question them. Social experiments are a wonderful way to discover someone else’s key predicaments, and make superb projects for documentary-makers. The situations revolve around the fundamentals of character, obstacles, inventiveness, and struggle, all of which determine the outcome (or resolution).

Cycles of character/problem/escalation/crisis/resolution form units that dramatists represent through a dramatic curve or dramatic arc, whose build-up, peaking, and downturn look rather like a fever patient’s temperature chart (Figure 18-6). The concept comes from ancient Greek dramatic theory by graphing each story-unit (scene, act, or entire drama) as rising pressure. It states the central character’s problem, and maintains dramatic tension through events of increasing intensity and complication, until arriving at an apex or crisis. Following this comes the resolution —though not, let me emphasize, one that is necessarily happy or peaceful.

You seldom know how a documentary shoot will turn out, but even in research it is good to imagine where you might place available materials along the film’s imagined dramatic arc. You can apply it as a template for an entire story, or use it to help you identify the changing dramatic pressures in a single scene. Knowledge of the concept helps you to decide, as you shoot a scene, where you are, dramatically speaking, during an argument between two children in a playground, or in a dispute over the validity of a discount coupon. When it comes to postproduction, the dramatic arc, like the three-act structure with which it is closely associated, provides superb guidance for how to orchestrate the story’s rising and falling pressures.

To begin deciding a scene’s dramatic shape, first nail down its pivotal point, or crisis. This is the turning point of maximum pressure, struggle, and change. In Nicholas Broomfield and Joan Churchill’s Soldier Girls (USA/GB, 1981), it is probably where Private Johnson, after a series of increasingly stressful scenes of conflict with authority, leaves the army dishonorably but in a spirit of relieved gaiety. After this major character leaves the stage, the film’s resolution is to examine more closely what soldiers need during training to survive battle conditions.

In the Maysles Brothers’ Salesman (USA, 1969), discussed in Chapter 3: Documentary History, most people consider the story’s apex to be the moment when Paul Brennan, the salesman falling behind the pack like a wounded animal, sabotages a colleague’s sale. In the film’s coda, his partners have distanced themselves as if from contagion, and the film’s resolution is a shot of Paul gazing offscreen into a void, as if staring mesmerized at his oncoming fate (Figure 18-7).

No matter what unit of drama you analyze—whether a dramatic unit in a scene, or an entire movie—the whole cycle emerges once you have pinpointed the apex or crisis. Commonly, around two-thirds of the drama precedes the crisis, and a third follows it. By taking Soldier Girls we can examine the three-act structure so you can make use of them:

Hollywood uses the three-act formula with awful fervor, and some screenwriting manuals even prescribe a page count per act, with actual page numbers at which plot points should occur (a plot point takes the story off at an unexpected tangent). Documentary is far too wayward to permit such iron control, but it must give its audience dramatic satisfaction too. The same dramatic form remains true for essay, montage, or other forms of documentary, not just those featuring physical struggle.

Indeed, you can find this dramatic form—escalation of pressure up to a crisis, then a lowering pressure after the resolution—expressed in songs, symphonies, opera, dance, mime, and traditional tales—all the time arts, in fact. It is as fundamental to human existence as breathing or sex.

A successful documentary scene will often reproduce in microcosm a similar dramatic curve of pressures that you see on a large scale in a whole work. A scene is thus a drama in miniature. Even compilation montage films about nature that lack any foreground characters, such as Pare Lorentz’s The River (USA, 1937), or Godrey Reggio’s Koyaanisqatsi (USA, 1982), use the same cyclic building and then release of pressure. The documentary director orchestrates this—either in the cutting room, or from behind the camera at the time of shooting.

In real life things are not so tidy. For every human interaction that spontaneously fulfills the dramatic arc, ten others suffer delays, paralysis, or regression. In observational documentary, you are left frustrated and impotent, but in participatory documentary you can do something about it.

When a scene develops, spin its wheels, and refuses to go anywhere, some judicious side coaching (verbal inquiry or prompts by the director from off-camera) can help the characters work at an issue differently and produce a significant change. Skillful editing can now make the scene function without looking assisted in any way. But, you protest, that isn’t true to life or honest! You can argue with some justice that, providing your side-coaching helps the participants reach their own solution, the results on film serve the spirit of truth if not its literal word.

When the director feels responsible for the main character’s progress, as Steve James does in Stevie (USA, 2002, Figure 18-8), he cannot avoid becoming a player in Stevie Fielding’s struggle with himself. James can pose questions, suggest options, ask for memories or ideas that Stevie might think of for himself, were he less beset by demons.

In such a situation, the participatory director becomes a surrogate for the audience, pursuing what the audience wants elucidated, and applying pressures the audience might apply were it, rather than James, confronting Stevie. Becoming the film’s interlocutor in this way carries responsibilities, since the director can misuse his weight to exert moral censure, judgmental righteousness, or to claim that what Stevie has done wrong is justified. If so, the director’s values and sensibility are now out in the open for the audience to assess. To acquit him- or herself well, the director must work carefully from clues manifest by the person under scrutiny. In fact, once you become attuned, you can develop strong intuitions, and do all you can—verbally and nonverbally— to midwife new stages into being. How can this be? And how is this connected with dramatic form? We must now look at another important moment in drama which you should recognize.

In dramaturgy an important moment of change in a character’s consciousness is called a beat. Let’s be quite clear that this has nothing to do with music, rhythm, or a moment of delay (as fiction screenplays sometimes demand). A dramatic beat is a fulcrum point, a moment of irrevocable change. Well-trained actors know beats as turning points in each of the dramatic units that make up a well-written scene. You might have a touching moment when a mother realizes for the first time that her daughter loves her: well, that turning-point moment is a beat! It might be a pickpocket realizing he is trapped in a subway train. Another beat.

In neither scenes do other characters notice anything, but the character under scrutiny (along with us, the audience, of course) recognizes that the character has (a) gone through a moment of irreversible change, and (b) must now act differently.

The documentary director busy shooting life must understand this principle, and learn to see beats forming and happening before his or her camera. Two friends maneuvering a new fridge through a narrow hallway might yield a series of beats:

They puff and pant getting the fridge to the doorway

Obstacle A: They realize it’s too big to go through the doorway (Failure, beat).

Strategy: They confer, measure it, realize it’ll go through if they remove the door (delay while they find tools). Remove fridge door and interior shelves.

Try again: it’s lighter (Success, beat). Rejoicing: it goes through the doorway.

Obstacle B: Now it won’t go under a rigid light fixture.

Strategy: Too complicated to dismantle fixture, so must lie fridge down lengthways.

They back it into doorway, roll it forward, get under the fixture and (success, beat) move forward

Obstacle C: The fridge is too long to get past the bottom of a protruding staircase.

Strategy: They must roll the fridge upright again. They are getting tired and irritable with each other.

They try this and it works (success, beat). With difficulty they can maneuver the fridge into the kitchen (resolution.) Mission accomplished, weary high-fives.

Finding the solution to each obstacle requires a strategy. Whether it fails or succeeds, it’s probably a beat, the proof being that they have to change tactics. If another approach works, the problem is solved, and so another beat, a new problem, and new strategies. Solving one problem usually leads onward to a new one, and so on. Thus when two people try to accomplish something, each dramatic unit normally includes:

● Realizing there is a problem and agreeing or not agreeing on what it is.

● Pursuing an agenda which may be mutual or not.

● Complications arise to raise the stakes (which makes success all the more imperative).

● They approach the crisis (apex of their efforts).

● Their final make-or-break strategy either works or doesn’t, leading to a beat that is the crisis —the highest point of struggle and change.

● Resolution (outcome) leads on to a new issue or problem.

In dramatic tradition there are three main types of conflict—two external, one internal:

● Man against man.

● Man against nature.

● Man against himself.

It is fatally easy, indeed strangely universal, to define a situational conflict inadequately or downright wrongly, which will distort or even destroy the course of your film. A woman who tries to rescue family photos during a flood is not in conflict with the photos, or over the photos, but with the overwhelming forces of nature that threaten to destroy her history. A young actor struggling to overcome her sheer terror at going onstage for the first time is not in conflict with the play, or with the situation: she is in conflict with her own fear of failing, which makes it “woman vs. herself.”

Always doubt you’ve properly located the conflict in whatever you are witnessing or shooting—it’s a very slippery and deceptive concept and worth double-checking. In the refrigerator example above, the conflict is not men vs. fridge, because the fridge is not putting up a fight. It is simply being its awkward, lumpen self. Surely the conflict is “man vs. man” since the action is two individuals arguing their way through the difficulties of teamwork. The fridge is the catalyst for difficulties which cause them to try to cooperate. Define the locus of conflict properly, and you can shoot it well. Misidentify it, and you’ll shoot the scene wrongly.

Make a practice of recognizing beats taking place around you in daily life. Count the beats in each scene, and imagine how you’d film them. For the fridge scene, how much attention should your camera give to the fridge? How do you show the obstacles? How much should you dwell on one or other of the two men? What character traits do they manifest during their struggle, and how can you bring them out?

When dramatic units follow one after another, your film is breathing, in and out. Recognizing dramatic units in life, covering them sensitively with the camera as they take place, and editing to expose their essential nature is a skill supremely important to your directing, no matter whether in fiction or documentary. Very few people master this, so if you can teach yourself such awareness, and capture it on film, your work will register immediately as somehow superior.

A successful progression of beats hikes the dramatic tension. It sets up questions, anticipations, even fears in your audience. Never be afraid when editing to make your audience wait and guess what comes next. “Make them laugh, make them cry” said the father of the mystery story, “but make them wait.” 4

From now on, think of yourself as a dramatist, someone who specializes in profiling character, development, and destiny. Many times, as you shoot a situation’s progression, the scene stalls instead of resolving into the change you anticipated. Perhaps somebody’s aspiration leads to failure or flies off at a tangent (in dramaturgy this is a plot point). Now you see an entirely new cycle of problem, complications and escalation. Or maybe you see that the scene is simply hanging. If you are shooting participatory rather than observational documentary, you can try breaking the log-jam with a well-considered question, or by suggesting an action of some kind. Alternatively you might cut the camera and confer with the participants before proceeding.

Once you can recognize where any moment of an unfolding scene lies on the dramatic arc, you can direct more intuitively. To get there, work on your insight during the everyday activities around you—in the post office line, say, as a grumpy clerk tries to persuade an obtuse customer to step aside and fill up a different form. Often you will see scenes of tension in which someone grapples with obstacles, handling them from the entrenched perspective of their own agenda. Scan along the dramatic arc by asking yourself:

● His/her problem is …

● The inciting moment was …

● The agendas for each of the characters are …

● The complications in the situation are …

● The crisis came when …

● And the resolution or outcome was …

Seeing ahead of the participants in a human interchange, you are forewarned and ready for what they might do. Even more important is that your camera operator be so too.

No matter what kind of cinema you are making, your responsibility is to see, understand, and shoot dramatic units because they are the piston strokes of powerful drama.

Satisfying stories generally have momentum (forward-moving energy). The key lies not only in givens (who/what/when/where) and the characters’ agendas, but in the obstacles that build up an energy field by providing resistance. To depict this in his teaching, my Australian friend Russell Porter uses his Dead Fish Analogy (Figure 18-9). The head is the beginning of the film, the tail is its end. Any story with momentum has a strong backbone leading surely from head to tail. This is usually indicated in the Hook, or “Contract,” which indicates the direction and purpose of the story in the film’s first minute or so. Once the momentum and reliability of the spine is established, you can afford to have ribs, each representing a sidebar excursion.

Imagine applying this to a hypothetical project about walking the medieval pilgrim’s trail from the Pyrenees to Santiago de Compostela in Spain. Once the pilgrimage is established and begun, you can leave the trail along the way to visit Pamplona, Burgos, Leon, and even small villages. The spine represents the goal of traversing the pilgrim’s way, and the tail is the magnificent cathedral of Saint James, always there as the film’s goal.

Any strong idea is like this. It might be a man’s quest for the father he hardly knew, as in Nathaniel Kahn’s My Architect (USA, 2003, Figure 18-10). Having established the primacy of his mission, Nathaniel can take time to visit Louis Kahn’s buildings around the world, talk with the women in his father’s life, and question the architects he knew and influenced.

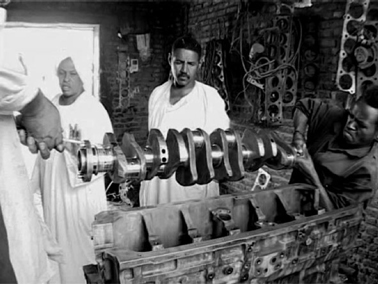

In their ethnographic study Sifinja—the Iron Bride (2009, Sudan/Germany, Figure 18-11) Valerie Hänsch and Kurt Beck study an extended family in Sudan who renovate a classic brand of British truck. The spine of the film is not a journey or a stretch of time, but a proud declaration by the desert craftsmen that they can keep these Bedford trucks going forever. The film proves this by showing their resourcefulness at using basic tools and techniques to rebuild engines and transmissions, and repurpose suspensions and bodies to accommodate local needs. This is a process film whose development is the truck’s rebirth as a brightly painted, bedecked galleon of the desert, piled high with goods, people, and clucking chickens.

FIGURE 18-9

Russell Porter’s dead fish analogy for dramatic structure.

FIGURE 18-11

The spine of Sifinja is not a journey or a stretch of time, nor even a process. It is the desert craftsmen’s proud declaration that they can keep elderly Bedford trucks going forever.

The sidebar excursions deal with the ingenious though primitive resources by which they solve mechanical problems, the customs and humor of the country, and competition looming on the horizon as customers desert the Bedford for a larger, newer truck. The film implies that when human beings have skills, pride, and a social system valuing humor, they can be endlessly creative.

Many life situations have foreseeable elements. Imagine you are going out with a fire engine company to document the impact of a fire on a family. What can you predict? As research, you question the engine crew on typical fires—and they will have much to tell you. You learn that every event has a predictable course with inevitable givens (in this case, causes and effects), and so with some forethought you can be fairly sure your story will include:

● How the fire started.

● How people tried to stop it.

● How it spread.

● What neighbors did—heroic or otherwise—to save the victims.

● How far the fire got before coming under control by firefighters.

● What the family lost that mattered to them.

● What the consequences are for their lives thereafter.

You can even see where each element might belong in the three-act structure. Now you can collect material and come away with coverage that practically guarantees the elements of a full story. Most importantly, you have envisioned what outcomes to expect, since any one of them provides the all-important development that saves your film from getting no farther than stating the obvious. Even though everyone escapes without physical harm, there is a great deal of mental suffering, and you become the witness to this. You might even follow your family for months or years afterwards.

Most narratives tell the chapters of their tale in chronological order, but you can do otherwise if (a) there is a compelling reason to organize them differently, or (b) because basic chronology is weak, absent, or unimportant to the angle (storytelling purpose or emphasis) of the story.

In plenty of reports on extreme situations like refugee camps and hunger, nothing changes, leaving the viewer feeling impotent and hopeless about humanity. It’s the kind of portrayal that has stereotyped Africa as a continent of passive victims, when much today is positive and constructive there—socially and economically. My own feeling is that narrative art is an indulgence if it does not find evidence of growth and change somewhere. The problem is that most human growth is very slow, and the documentarian cannot always stay around to show it.

If you can’t afford a long shooting period, choose your subject carefully. When long-ago I worked on a BBC series called Breakaway, we skirted “non-event films” by building a series around people undergoing major changes. My two films were about people choosing to migrate abroad, 5 but another followed an elderly person into a retirement home, and a third chronicled an apprentice ladies hairdresser deciding to join “a man’s world” in the Army. Each film had a clear “before” and “after”—and a major, assured turning point as the apex of the dramatic arc.

The list that follows, not meant to be definitive, is of common documentary types that each imply structures.

An event, especially one that is familiar, often provides a strong, clear structure. Its stages become the vertebrae in the film’s temporal spine, and provide a strong sensation of forward movement. Once the event is under way, its momentum lets you plug in sidebars (the ribs along the spine) knowing that the audience is always ready for the story to revert to the temporal spine’s next stage. These digressions might be sections of interview, pieces of relevant past, or even pieces of the imagined future.

Some events, such as a marathon race or a political rally, move fast or have many unfolding facets. Leni Riefenstahl’s dark classic, Olympia (Germany, 1938, Figure 18-12), presents the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games in this way and places Hitler and the German contestants with seductive virtuosity at the center of a mass of events that Riefenstahl references to the heroic deeds of antiquity.

FIGURE 18-12

The beauty of sports seen through National Socialist eyes in Olympia. (The Kobal Collection/Olympia-Film.)

When multiple strands of narrative are happening simultaneously, you may need multiple camera units. I directed one such unit in a series called “All in a Day”: the film was about an aristocratic pheasant shoot, and my unit tracked the gamekeeper. Any situation having multiple actors that runs its course in a predictable span, such as a court trial, spelling bee, or rodeo, is likely to have just as predictable a shape and structure. Its “unknowns” will be who or what predominates in the welter of action. To cover one like this, divide the activities into stages, and carefully brief each unit to cover particular aspects of each stage, since your film must be able to indicate what is expected by the audience. Plan carefully or the units wander into each other’s fields of vision by mistake. Knowing you have what is vital pinned down, your units are freed to record the unexpected along the way.

A process is any sequence of events that produces or accomplishes something. Building a shed, taking a journey, or getting married can transcend the banal and become fascinating if you can reveal them as atypical, archetypal, or metaphorical. Like event films, process films are modular, each stage having its own arc containing beginning, middle, and end. Usually you show them in chronological sequencing, but you can use parallel storytelling to intercut multiple events or processes by weaving together the multiple story strands pioneered by Dickens in his novels. A father may be at work in a factory, for instance, while his daughter is in school getting the education that allows her not to work in a factory. As each sequence advances by steps, the characters and their predicaments develop in a linear fashion, and, most importantly, you can imply meanings and create dramatic tension by juxtaposing particular actions. By allowing you to make only minimal references, parallel storytelling permits brevity and a potent form of authorial comment.

A three-year longitudinal study like David Sutherland’s The Farmer’s Wife (USA, 1998, Figure 18-13) chronicles the effects of relentlessly growing economic pressure. The process in question—shocking in the world’s wealthiest nation—is slow starvation for a Nebraska farming family. Blow by blow, and in extraordinary intimacy, we see Darrel and Juanita Buschkoetter struggling to stave off bankruptcy. Culled from 200 hours of footage, the film shows many poignant, lonely episodes that play out as sustained husband/wife interactions. Each is filled with tension, and many become the kind of dramatic experience you could only hope for in a strong theatre production. During the six one-hour episodes, Darrel doggedly works multiple jobs while she holds the family together and finishes college. Eventually it is her strength of character that pulls them through—hence the series title. Over the three-year span, Juanita matures from girl to woman, but their marriage suffers badly.

FIGURE 18-13

Longitudinal study of a farming family under extreme duress in The Farmer’s Wife. (Photo courtesy of David Sutherland Productions.)

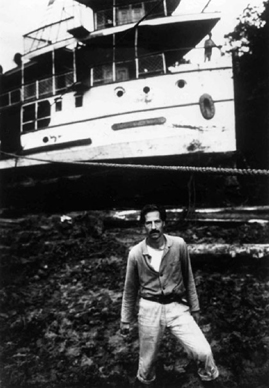

Les Blank’s Burden of Dreams (USA, 1982, Figure 18-14) chronicles the making of Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo, a fiction feature about a real-life opera impresario who contrived to drag a river steamer over the Andes. Blank documents Herzog’s own struggle to get a steamer up a jungle mountainside, and reveals how a cherished project can become more important to its director than the physical dangers faced by his workers. Herzog’s objectives and values revealed by the process become metaphors for the ruthlessness that often lurks under the guise of making art.

FIGURE 18-14

Werner Herzog and the boat he hauls up a hillside in Les Blank’s Burden of Dreams. (Photo by Maureen Gosling.)

Journeys promise change and development. Luc Jacquet’s March of the Penguins (France, 2005, Figure 18-15) shows the epic journey that Emperor Penguins make in the Antarctic in order to breed. Some do not finish the journey, find a mate, or manage to guard their chicks, so the film has periods of fairly awful suspense. The struggle to survive has such anthropomorphic resonances that for some the film exemplified “family values.” Apparently, the French version had a set of voices speaking as if for the penguins (which sounds truly awful). More conventionally the English version uses the omniscient, voice-over narration dear to National Geographic, which coproduced. Gripping and worth studying for its editing alone, the film orchestrates much mass action and movement culled from a year of shooting. Luckily penguins do similar things and all look alike, so you get extraordinarily detailed coverage of each stage during their long and arduous journey.

Jorge Furtado’s 13-minute Isle of Flowers (Brazil, 1989, Figure 18-16), once voted a most important short film of the twentieth century, follows the brief life of a tomato as it starts at the growing site, follows it being made into sauce, and then watches its dregs finishing up in the municipal dump. The film has virtuoso montage sequences, and as you can guess, tomatoes become metaphors for human beings. The film shocks its audiences by suggesting how despicably an industrial society treats the powerless.

FIGURE 18-16

The municipal dump in Isle of Flowers where the tomato we have followed is flung out to die amid the trash.

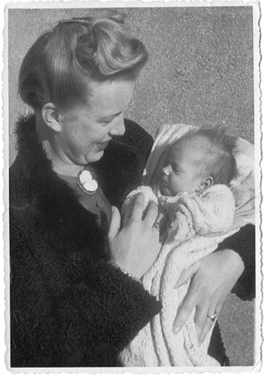

In Lars Johannson’s The German Secret (Denmark, 2005, Figure 18-17) the filmmaker chronicles his wife Kirsten Blohm crossing Europe in search of the Nazi father whose identity her mother refused to divulge until near death. Amazingly, there are still people alive 50 years later along the route who remember the beautiful, haughty blonde with the strangely neglected child. Piece by piece, Johannson and Blohm establish the truth, which shapes up to be very far from what they expected. In this tender and masterful film that is replete with intimate reflection and intense, sustained encounters, Kirsten’s painful journey delivers only partial liberation from a legacy of doubt and anger.

Strictly speaking, all film is history since every frame, no sooner recorded, becomes a preservation of the past. Film ought to be a good medium for historical films, but is not always so. More than most story forms, histories must often digress to build their tributary chains of cause and effect. Imagine a film about a plane crash in which all six of an airliner’s safety features failed. You have a known outcome, but your film must spend most of its time explaining what each safety feature is supposed to do, how it failed, and what its breakdown contributed to the disaster. Here, in a tale of causality, time becomes of minor importance.

FIGURE 18-17

Mother and daughter in The German Secret. Who was my father? Why won’t you tell me? (Photo courtesy of Lars Johansson.)

Even the makers of screen history themselves aren’t always satisfied, as Donald Watt and Jerry Kuehl have pointed out. 6 Many history films, as they assert,

● Bite off more than they can chew.

● Commandeer specific images as backdrops for generalizations.

● Are inherently unbalanced whenever there is no archive footage for important events.

● Fail to recognize that the screen is different from literature or an academic lecture.

● Are often dominated by unverifiable interpretations.

● Try to sidestep controversy as school textbooks do.

● Fail to enlighten their audience about strings attached to funding.

● Suffer because their makers wanted to build a monument.

● Fail to acknowledge that historians find what they look for.

● Suggest consensus opinion, and gloss over vital disagreements.

To this we can add that, by its realism and ineluctable forward movement, the screen history discourages contemplation and tends to glide over what it can’t illustrate. Historical meanings are in any case abstractions, and the screen is inherently better at dealing with what is materially audible and visible.

We should be skeptical when a film uses omniscience to obscure its sources. The all-knowing narrator guiding us through tracts of history is worrisome, especially in those History Channel series that use archive footage to cover vast thematic and factual territory. In Britain, Thames Television’s 26-episode The World at War (GB, 1973–4) and in the USA WGBH’s Vietnam: A Television History in the 1980s each echo a textbook emphasis on facts. How much more relevant they would now seem, had they tackled the thorny issues of the time, which are now more pronounced than ever with the lapse of time. Even Ken Burns’ The Civil War (USA, 1990), which counterpoints contemporary accounts and photographs, overwhelms the viewer with the repetitive minutia of its period when the viewer longs for larger dimensions of understanding.

Some screen histories succeed in this. An openly critical one-off film like Peter Davis’ Hearts and Minds (USA, 1974, Figure 18-18) argues by analogy that the American obsession with sports provided a tragically misleading metaphor for the US involvement in Southeast Asia. Here the viewer is on a clearer footing and can engage with the film’s propositions rather than go numb under a deluge of uninflected information.

Eyes on the Prize (USA, 1990), a PBS series from Blackside, Inc., provided a highly effective historical perspective which chronicled the development of the American civil rights movement. It managed to tread a fine line between historical omniscience and personal testimonies that were imbued with commitment. Though crew members were carefully chosen for racial balance, you are never in doubt that the film speaks on behalf of black people, so egregiously wronged in equality-proclaiming America.

The War (USA, 2007, Figure 18-19), directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, is an oral history whose excellently chosen witness/participants each tell their stories in what adds up to multiple viewpoints. Unlike Burns’ earlier, seemingly more linear and event-bound histories, its voice is free of patriotic hubris, and presents a forcefully non-nationalistic, anti-war perspective that is hauntingly tragic. This comes as a timely corrective when embedded journalism has presented so many hapless American soldiers as heroes fighting foreign evil in the Middle East. Even if World War II was the nearest thing to a just war, The War makes it clear that all parties committed crimes against humanity, because inflamed or terrified soldiers commit atrocities as part of their bid to survive.

Following a single character through time is a variation on the hero’s journey paradigm of the folklorist Joseph Campbell. 7 Point of view plays a significant part, since the central character’s sense of events is often in tension with that of his or her contemporaries. Usually the main character meets a challenge, refuses it, meets a more urgent version, goes on the journey, and develops by meeting test after test.

Peter Berggren is a Swedish filmmaker resident in the USA who specializes in musical biography. His joyous observational documentary Chick ‘a’ Bone Checkout (USA/Sweden, 2007, Figure 18-20) follows the Swedish composer Christian Lundberg writing a trombone concerto for virtuoso Charlie Vernon of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. The true biographical subject is their collaboration, and it culminates in a performance of the concerto itself and a memorable encore by soloist and composer dressed as Chicago gangsters.

In My Name is Celibidache (Sweden, 2013), Berggren takes a different approach. Elderly musicians of the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra recall the amazing development in their orchestra under Sergiu Celibidache, its moody, charismatic Romanian conductor. The film moves chronologically through the conductor’s tenure using an effortless and lyrical layering of imagery in which interviews float over archival footage of rehearsals and concerts. The true subject of the film is the phenomenon of artistic leadership by a conductor, and we learn how Celibidache’s methods and personality were the inspiration of a lifetime for some, and a long ordeal for others.

A common break with chronological time is to show an event and then backtrack to analyze the interplay of forces that led up to it, as Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky do in Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills (USA, 1996). The film opens with the tragic prospect of three murdered eight-year-old boys, and then focuses on the trial of the three local teenagers accused of killing them in a satanic ritual. The film casts doubt on the validity of the evidence, rather as the filmmakers did in their earlier Brother’s Keeper (USA, 1992), which tells of some reclusive rural brothers accused of mercy-killing a sibling. Both films examine the arguments for and against each allegation by deconstructing the evidence, and then inviting us to draw likely conclusions like a jury. These are films interested not just in clarifying facts but in showing how poorly people separate reliability of character from stereotype. This takes their films deeper into social criticism than the conventional investigation.

FIGURE 18-21

The Person of Leo N: Nature’s cruel joke—to be a woman in a man’s body.

A train journey is central to the operatic intensity driving Alberto Vendemmiati’s The Person de Leo N (Italy, 2006, Figure 18-21), mentioned earlier. The journey proves to be the most fateful in Nico’s life—it leads to the operating theatre where surgery will alter Nico’s physical gender to fit a lifelong sense of identity as a woman. Along the way, there is a complex of flashbacks, including sequences of actors in masks, all associated with Nico’s anxious and shifting preoccupations. What could possibly be more destabilizing than to be identified wrongly by gender, and to have to hide one’s very essence? The flashbacks establish Nico’s troubles in early life when treated as a boy, her loneliness as a misfit adult, and her patient love for her mother, who has never fully accepted that her son feels like a daughter. The handling of time matches the complexity ofinico’s shifting consciousness while she gathers courage to gamble everything on the operation. The overriding questions that hang over the whole masterly narrative are Nico’s own doubts: “Will my mother accept or reject me?” and “Will I find love at the end of all this?” The film finds an answer to both.

By exploring a mode of observation, mood, or belief, this category usually privileges imagery and metaphor over time. All the best documentaries have poetic elements, of course, but too few build laterally on the power and associations of imagery. Some are discussed in Chapter 5: Story Elements and Film Grammar, the most memorable being Land Without Bread (Spain, 1932), Night Mail (GB, 1936), The Plow That Broke the Plains (USA, 1936), and The River (USA, 1937). Humphrey Jennings, “the only real poet that British cinema has yet produced,” 8 made memorable documentaries during World War II while his country was under siege, notably Listen to Britain (GB, 1942), Fires Were Started (GB, 1943, Figure 18-22), and Diary for Timothy (GB, 1945, Figure 18-23). Their emotively loaded imagery and evocative sound design spoke deeply to the generation that lived through the events. In Fires Were Started Jennings alternates appallingly vivid actuality footage of London in flames with improvised firehouse scenes that use conspicuously stilted dialogue.

FIGURE 18-22

Making Fires Were Started, an early dramadoc that united horrific firefighting footage with improvised dialogue scenes among the firemen. (Photo courtesy of The Kobal Collection/Crown Film Unit.)

The common, perhaps highly significant, denominator is that all these filmmakers shot silent, concentrating on a logic of imagery first, and composing sound separately and later. The message? The order in which you do things absolutely determines where you end up.

Some biographical films I specially admire are hard to find. Orod Attapour’s Parnian (Iran, 2002, Figure 18-24) profiles an ill-fated family of Teheran archeologists. Both mother and son suffer from an incurable wasting disease that is visibly killing the mother. The father cares for them both while he and his son probe Iran’s rich archeology with obsessive, desperate commitment. Every sequence carries richly poetic overtones, and every image reverberates in metaphorical relationship to others. Like the Persian poetry plainly influencing it, the film draws out a tragic vision of life as a wheel whose spiraling patterns bind us to those who lived and suffered before us—a message about the cyclical nature of existence similar to that in a famous Iranian novel, The Blind Owl. 9 Both works assert that we dwellers in the present must live and suffer as our ancestors did, and yet lead the way for those who follow. Miraculously compressed into Parnian’s austere half-hour is a whole vista of time, repeated destiny, decay, and renewal.

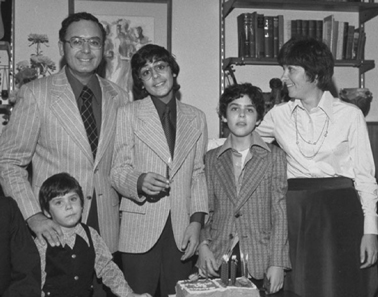

Two distinguished films probe family secrets and find surprises and heartache behind “successful” lives. Each film eschews chronological time in favor of the order in which significant new information surfaced. Andrew Jarecki’s controversial Capturing the Friedmans (USA, 2003, Figure 18-25) follows up the arrest of a respectable Long Island teacher and one of his sons for alleged sexual crimes against children. The film gathers all available family perspectives, looks at the 8 mm home movies of the archetypal suburban family at happy play, and finds in the end that nothing adds up and all is mystery. As so often, family members remain strangers to each other.

FIGURE 18-25

A family harboring molesters in Capturing the Friedmans, or a miscarriage of justice? (Photo courtesy of The Kobal Collection/HBO Documentary/Notorious Pictures.)

In Doug Block’s 51 Birch Street (USA, 2005), a son goes in search of the truth behind his parents’ long but blighted marriage, hoping to reach his father after his mother dies. In the writing she left behind, Block is astonished to discover that the mother he thought he knew had maintained a secret love life. His father, who always seemed remote, suddenly marries his secretary of 40 years ago, and emerges as warmer and far more understanding of his dead wife than Block had ever imagined possible. Truth does indeed set you free.

Each of these biographies begins from some basic questions that, pursued through a labyrinth of ambiguous discovery, unfold like a detective story. Following clues and pursuing hypotheses, their protagonists lance at layers of protective myth and stereotype. It is however association and the hierarchy of discovery that determine the films’ structures. Both pursue a crooked course, but high intelligence and sophistication make each seem to have taken the only path possible.

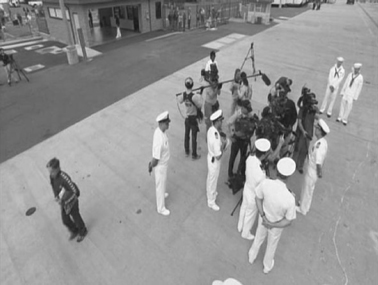

Societies, institutions, and tribal entities define their boundaries, close in upon themselves, and develop self-perpetuating codes. Films that profile them are often impressionistic and shot with multiple cameras since their boundaries often enclose many simultaneous activities. Juxtaposing these by theme, mood, or meaning can imply polemic by using the light hand of montage. The 10-hour PBS special Carrier (USA, 2008, Figure 18-26) aspires to be the mother of all such endeavors, though its subtitle (“One ship, five thousand stories”) may seem more like a warning. Conceived by Mitchell Block and its director Maro Chermayeff, it draws on 1,600 hours of superb handheld filming during six months’ residence aboard the nuclear-powered US aircraft carrier Nimitz. Each hour-long episode handles a theme (“controlled chaos,” “show of force,” “rites of passage”) and each is bookended with title sequences that are unfortunately redolent of recruiting films. Do not be put off, even though most episodes are diffuse, high on testosterone (the average age aboard is 19), and punctuated with upbeat songs that seem suspiciously like narrative aids. The series is worth seeing from beginning to end as a thorough study of a military society riddled with contradictions and conflicts. Sailors of both sexes and all ranks are remarkably candid, and the unfolding stories of the 15 central characters become the series’ connective tissue. We come to see a rare camaraderie that compensates for the turmoil and pain often lurking in the sailors’ dysfunctional family origins. Most suffer excessively because of long periods of separation from their loved ones, as do the families they leave behind on land.

FIGURE 18-26

Filming Carrier, an encyclopedia of military culture and a compendium of advanced documentary techniques and situations.

The sheer enormity of the series in relation to its enlightenment leaves you feeling ambiguous. Unintentionally, I think, it glamorizes military life and celebrates the gunboat diplomacy for which vessels like the Nimitz were created. The unspoken issues—why America chooses military might over domestic social justice, healthcare, and effective public education, and why military might makes ideological enemies rather than beats them—remain outside the film’s sphere of attention. As with many documentaries, you are left wondering what restrictions the filmmakers accepted— or imposed on themselves—as the price of filming.

Most of Frederick Wiseman’s documentaries—at long last available on DVD—are walled-city films, most notably two of his earliest— Titicut Follies (USA, 1967) and High School (USA, 1968). The Titicut Follies is a revue presented by the staff and inmates in a Massachusetts prison for the criminally insane. Wiseman makes it function both as a spine for the film and a grimly nihilistic metaphor. When you make films without to-camera interviews or narration you cannot retreat from scenes that are grippingly horrific. What we see might be retrieved from the eighteenth century, for in stark, Daumier black-and-white imagery we see the inmates’ degrading spectrum of daily experience—from induction, psychiatric evaluation, nakedness, forced feeding, to burial. In one sequence, a seemingly sane Hungarian tries desperately to extricate himself from the institution’s nightmarish embrace. In another, a psychiatric doctor with an ash-laden cigarette quivering on his lower lip rams a feeding pipe down a half-dead prisoner’s nose. Each digression from the ongoing revue is so engrossing that the revue itself becomes a mocking commentary. Wiseman and his cameraman Bill Brayne lead us into a living hell, and at the same time define for all time what observational documentary can accomplish.

Two films by Nick Broomfield—Soldier Girls (USA/GB, 1981, with Joan Churchill) and Chicken Ranch (USA/GB, 1982, with Sandi Sissel, Figure 18-27)—qualify as walled-city films but differ significantly in approach from either narrated or observational approaches. Soldier Girls looks at women soldiers in basic training while Chicken Ranch is about the women, their relationships, and their customers in a brothel. Both explore social ghettoes and find their structure in a series of events that occurred spontaneously during the filmmakers’ residency. Both show how those in charge of institutions try to condition and control their inmates, and though neither pretends to be neutral or unaffected by what it finds, each leaves us more knowledgeable and critical. By letting us see a discharged woman soldier in Soldier Girls embrace the camera operator, by including the brothel owner’s tirade at the crew for filming what he wanted kept confidential, each admits where the filmmakers’ sympathies lie and hints at the liaisons and even manipulation that went into their shooting. Broomfield has since made Battle for Haditha (GB, 2007, Figure 18-28), a documentary-style re-enactment of the 2005 killing of a marine by a roadside bomb in Iraq. When his colleagues fanned out to find the perpetrators, they killed 24 Iraqi civilians in a frenzy that the military tried to conceal.

Over time, a director’s own themes emerge, and Broomfield—coming as he does from a monarchist society with long traditions of colonial domination—is perennially fascinated by the ways that those at the bottom of the social pyramid are coerced into fulfilling their masters’ agendas.

FIGURE 18-28

Battle for Haditha: docudrama can sometimes say what documentary cannot. (Photo courtesy of The Kobal Collection/Channel 4 Films/Barney Broomfield.)

This is any film using the essay form to educate, analyze, or elaborate on a thesis. Exposés, agitprop, experimental, or activist films are often structured upon the stages of an argument or extended process, and often use montage to display ideas for the audience to consider. Let’s suppose you want to convince the audience that poor immigrants, far from draining the local economy, add economic value to a large American city. You must establish how and why the immigrants came, what work they do, what city services they do or don’t use, what their enemies say about them, and so on. You must build an argument and advance the stages of a polemic in order to overcome the skeptics among your audience.

Of the films mentioned in Chapter 3: Documentary History, Buñuel’s Land without Bread and Resnais’ Night and Fog both present impassioned views of how human cruelty works. The Pare Lorentz ecology duo, The Plow that Broke the Plains and The River , convey strong messages about greed and the rape of the land. Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 (USA, 2004) argues that the Bush administration, upborn after 9/11 by corporate media and embedded journalists, rode the wave of public feeling to further a prior agenda for invading Iraq and Afghanistan.

Hubert Sauper’s Darwin’s Nightmare (Austria/Belgium/France, 2004, Figure 18-29) draws chilling connections between the export of fish from Lake Victoria, the neglect and starvation of its native Tanzanian population, and the import of munitions used to fuel wars over Africa’s mineral resources. Alex Gibney’s Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (USA, 2005, Figure 18-30) built on work by Fortune reporters. It explains how the geniuses in the energy company kept double books in building their house of cards, and why it collapsed.

These are independent minds endeavoring to shine light into exceptionally dark places. Their freedom to argue rests squarely on the growth of accessible digital equipment, but remains limited by the fact that most film archives are corporately controlled and very expensive to quote. Meanwhile the Internet is developing as an uncontrolled arena for the exchange of information and opinion. History will probably judge public discourse to have changed radically at this time.

FIGURE 18-29

Poor fishermen in Darwin’s Nightmare watch the planes that took their fish to Europe return bearing guns.

This category’s main and enthusiastic purpose is to examine comprehensively rather than critically. A film about harpsichords, steam locomotives, or dinosaurs might organize their appearance by size, age, structure, or other classification. Unless the film takes the stages of a restoration or archeological dig as its backbone, time probably won’t play a centrally organizing role.

Joris Ivens’ Rain (Netherlands, 1929, Figure 18-31) is a silent, highly atmospheric 12-minute film shot over two years in Amsterdam. It reveals the sheer beauty of rain in a cityscape. A year earlier Ivens had shot another equally lyrical 11-minute classic, The Bridge. Both films explore a sequence of powerful moods, and will stand for all time as defining portraits of city life in 1920s Holland. With Borinage (Belgium, 1932), Ivens and Henri Storck turned to social justice in which concern for the misery of exploited miners replaced Ivens’ earlier interest in aesthetics. By showing how the men and their families lived from day to day, the film exposed to the rest of the world how a hidden and desperate part of European society existed.

Les Blank’s films, usually described as celebrations of Americana, are really catalogue films. There is Garlic Is as Good as Ten Mothers (USA, 1977), In Heaven There Is No Beer (USA, 1984), and that delightful examination of resourceful women who happen to have a space between their front teeth, Gap-Toothed Women (USA, 1987). All are good-natured forays into special worlds, and might seem voyeuristic were they not so kindly. The travelogue, diary film, and city symphony are frequently montage-based catalogue types.

There may initially be no obvious time structure. A film about stained glass windows may have none inherent in the footage. You could however posit a structure by dating particular windows, or arranging technical developments in glass manufacture, or dealing in turn with the region of the artifacts, or the origin and idiosyncrasies of the glassmakers. Which option you take depends on what you want to say and what your material best supports. Anthology films that chronicle a particular year sometimes take this approach.

Whether you are planning a film or confronting the dailies of one just shot, the structure you choose must accommodate some central concerns, so your options may not be as unlimited as you fear. Try answering these questions:

● How soon can your film gain momentum?

● How little exposition can you get away with, to get the film moving?

● Should you bunch the exposition (risky) or can you mete it out gradually? (Lack of essential information can be frustrating, or if well judged, prolong dramatic tension.)

● Does your film have a naturally inbuilt chronology?

● According to an event or process?

● Elapse of time?

● Journey?

● Other?

● What do you gain, and what do you lose, by sticking to that chronology?

● Does maintaining chronological order dissipate or focus the main issue?

● What stakes are your participants playing for?

● What can you do to raise them?

● Can you hold back your major sequences, or must you expend them early?

● What other aspects might structure your film?

● Catalogue order (by physical size, age, complexity, color, etc.)?

● By significance (in complexity, consequences, energy, etc.)?

● By significance to a main character (the order of recall, effect, consequence, etc.)?

● Narration (which might come from a character in the film)?

● What is the film’s likely turning point, or climax?

● Where can you place the film’s climactic scene(s) on the dramatic arc? Can it happen,

● At the beginning, so the film becomes an analysis of its major event?

● At the end, so the film builds toward its major event?

● Two-thirds through, as happens most often?

● What proportion of your movie’s screen time should you ideally devote to

● Getting to the resolution?

● Dealing with all the consequences that make up the resolution?

● How do you want your film to act on its audience?

● Mostly inform them?

● Take them through an intense experience whose outcome is unimportant?

● Make them think about causes rather than effects?

● Keep them guessing as long as possible?

● How else?

● Whose POV is the film channeled through, and how might this help you move away from the obvious structural solution?

● The main character?

● A subsidiary character?

● Multiple characters?

● The storyteller?

● Who or what changes and develops during your film?

● The POV character?

● Someone else?

● A situation?

● Where will this change probably happen?

● Is it gradual and in the background?

● Is it sudden, precipitous, and in the foreground?

● Is it the film’s climax?

● Where will your film’s dramatic tension come from?

● An overall situation that is long in developing?

● A volcanic, climactic moment? (Can you delay it and raise the stakes?)

● An impending change or crisis (such as a heart operation, say)?

Answering these questions probably won’t lead to ready solutions, but will get you thinking hard about your story’s essentials, which is the spade-work of creativity.

To log the contents of a documentary, write about the way its structure and style deliver its content, and describe what thematic statement it makes, use AP-7 Analyze Structure and Style. To experiment with the counterpoint of language and imagery, why not make your own short essay film using SP-9 Essay Film?

1. Michael Roemer, Telling Stories: Postmodernism and the Invalidation of Traditional Narrative (Rowman & Littlefield, 1995).

2. See “The Tradition of the Victim in Griersonian Documentary” by Brian Winston in Alan Rosenthal, ed., New Challenges for Documentary (University of California Press, 1988).

3. Heraclitus, c.540–c.480 BC.

4. Wilkie Collins (1824–1889) best known for The Moonstone and The Woman in White.

5. At the time I was unaware how central migration would be to my own family’s history: of 30 members, 25 have changed countries.

6. Donald Watt and Jerry Kuehl, “History on the Public Screen I & II,” in Alan Rosenthal, ed., New Challenges for Documentary (University of California Press, 1988), pp. 4318–453.

7. For the best, movie-oriented explanation, see Christopher Vogler’s The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Storytellers and Screenwriters (Michael Wiese, 1992).

8. According to the British director Lindsay Anderson.

9. Sadegh Hedayat, The Blind Owl (1937).