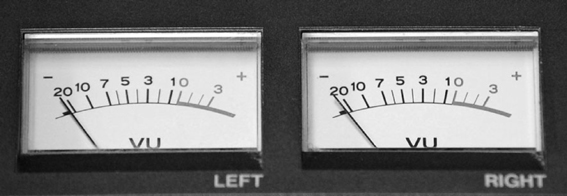

FIGURE 10-1

A sound recordist must continuously assess record-ing quality through professional, ear-enclosing headphones.

The eyes and ears of your documentary work are the camera and microphone. To make your work with each accomplished, you will need to understand their basic principles and techniques, and prepare for your first experiences of directing participants. A measure of inside knowledge will help you enjoy your work and make you an enjoyable and reassuring colleague.

Sound is the neglected step-sister in film, yet it is so important to drama of all kinds that I have placed it first among production concerns. The eye sees, but the ear imagines.1 Well-designed film sound creates its own emotively loaded reality, and even though the audience may not consciously be aware of this, it greatly affects them.

In early life, beginning an apprenticeship at England’s Pinewood Studios, my guide to music and to the wider significance of sound was my friend Brian Neal, who was not connected with the film industry at all. He had slowly lost his sight as a child and was declared legally blind in his early teens. At first it felt like a death sentence, but music became his great love, and from being a piano-tuner he rose to singing in Windsor Chapel Royal choir. He had a keenly humorous appreciation of the everyday world whose anomalies he would delight in sharing. He was a mimic as talented as Billy Crystal, and could tell you about his morning’s work by impersonating a running argument, complete with interruptions, between an old Polish couple whose upright he had just tuned. Afterwards you felt you had been there yourself, and had even tasted the little pastries they served.

So, yes, the eye sees, but the ear imagines.

Whoever shoots sound must continuously assess their recording quality through professional, ear-enclosing headphones (Figure 10-1). Not doing so always proves costly. Unless you are a musician, you will have to learn how to analyze the elements in film sound, and hear what makes it acceptable or otherwise. This means becoming an analytic and critical listener, which has its own rewards and pleasures.

In a highly stylized documentary such as Errol Morris’ dreamlike The Thin Blue Line (USA, 1988), or in Alberto Vendemmiati’s lyrical The Person de Leo N (2006, Figure 10-2), the imaginative canvas claimed by both filmmakers gives them great latitude for operatic or surreal soundscapes.

Memorable sound does not come from slavishly reproducing life’s complexity, but from concentrating and heightening a few selected sounds, as so memorably established during the French New Wave (see François Truffaut’s Jules and Jim, France, 1962 for its sound treatment). Particular sounds trigger particular associations and flights of imagination, a central assumption of psychoacoustics, the term describing how sound makes our minds perceive and interpret. The expert here is Michel Chion, whose Audio-Vision—Sound on Screen (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994) explains principles he developed over three decades. These are not simple, and require you to master a specialized vocabulary.

When you can visualize how sound behaves, your ear starts to discriminate. The sound terms below begin with the recordist’s main priority, and then move through the various obstacles and compromises that make sound work such a fascinating challenge. From a recordist’s point of view, every place and indeed every room in a house has its own soundscape, and only a highly attentive ear can pick out what makes it individual. We carry out a lot of this interpretation subconsciously, and perhaps this is what motivated the World Soundscape Project, begun in 1975, which is researching the acoustic ecology of six European villages. Sponsored by Tampere Polytechnic Institute in Finland, the goal is to record their changing acoustic environments over many decades (www.6villages.tpu.fi).

FIGURE 10-1

A sound recordist must continuously assess record-ing quality through professional, ear-enclosing headphones.

FIGURE 10-2

Through imaginative soundscapes and lyrical photography, Vendemmiati’s The Person de Leo N enlarges its story to operatic proportions. The film culminates in a reunion between Nico and her mother, who cannot see her as a daughter.

Any movie sound track has the potential to become orchestral in nature, something you can design from the outset to further the aims of your film. As you develop your documentary proposal, ask,

● What kind of world are you showing?

● What are its special sound features?

● What will you need to record, and how?

● What kind of impact should the sound track make at different junctures on the audience?

Sound terminology describes not only what sound is and how it behaves, but also what we feel about it—since sound and emotion are intimately related. First there is an assessment procedure.

To assess the acoustics of the sound environment at a location, a sound recordist gives a single loud hand-clap and listens intently (Figure 10-3). That brief, sharp sound is a transient that takes only fractions of a second to move through the air. It starts with a sharp attack, has almost no sustain (unlike a violin or piano note), but unlike the example in Figure 10-3 may have an audible decay if it reverberates between sound-reflective surfaces. A hand-clap in a tiled kitchen will sound live because it has a long and highly reverberant decay. This is quite different from one made in an upholstered parlor, where it will sound relatively dead.

FIGURE 10-3

Two hand-claps with virtually no reverberation seen as modulations on a timeline.

The recordist always aims to make a clean recording—whether a speaker’s voice, three cicadas chirping on a tree branch, or orange juice pouring onto cracking ice cubes. The sound you want is called signal. Everything that impedes it—interference such as wind noise, traffic, a distant playground, a gravel quarry, or aircraft overhead—is called noise. Using modern recording systems, appropriate microphone choices, and intelligent mike placement, you can achieve a good signal-to-noise ratio (abbreviated as S:N). The hissing in historic recordings, called system noise, was inherent to their primitive recording methods. The genius of Ray Dolby (1933–2013) eliminated it from the cinema experience, and digital electronics have done the rest.

Every location whether interior or exterior has its characteristic accompanying ambience, background, or atmosphere. This might be distant traffic, playground voices, the hum of a passing aircraft, or the nearby buzz of a fluorescent light fixture. The aim is to have it present in the completed film, consistent in level, and not intrusive. Creative recordists in their downtime collect all sorts of potentially useful “atmos” recordings. It might be the rustle of trees in a forest, the babble of voices in a canteen, or the hum of machinery in a power station. Atmospheres allow the editor not only to fill holes in dialogue tracks but to build a film’s tracks into an evocative sound composition.

A resonant space is one having a special note at which it resonates. You’ll know this from singing in your shower, and finding a frequency at which the room augments the note of your voice with its own sympathetically resonating frequency. An echo is caused by reflected sound traveling by a longer path, and arriving whole, but later than the signal.

Every room has its own atmosphere. Its components vary according to the season and time of day. No scene is complete until everyone goes rock still while the recordist makes a few minutes of presence track recording. This is also called buzz track, room tone, or ambience.

Like the human ear, a microphone employs a diaphragm. It is classed as a transducer because it transforms sound vibrations detected as varying air pressures into tiny electrical signals, which are then amplified. A loudspeaker is another kind of transducer because it changes electrical signals back into the air pressure variations by which sound travels.

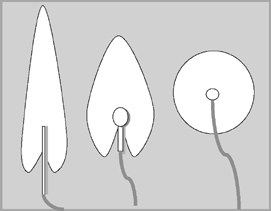

Mikes classed as omni-directional pick up sound equally from all directions, but a directional mike picks up sound best from its most receptive axis. This is called on-axis or on-mike sound. Other arriving sound is classed as off-axis or off-mike sound. Since directional mikes are designed to suppress off-axis sound, this sound records at a lower level. Thus directional mikes do not somehow zoom in and grab sound, they simply discriminate with varying degrees of effectiveness against off-axis sound (Figure 10-4). The ultra-directional microphone does this to the highest degree, but at some cost to the mike’s warmth and fidelity.

This is the sensation of changing sound direction and distance when a person walks away, a helicopter takes off, or a mechanical street-sweeper goes past. From sound alone we sense from the evidence of sound perspective whether a speaker is near, far, stationary, or moving. Without sound perspective, recordings lack something important. Though body mikes make a person’s voice pleasant and highly intelligible, they always have a certain deadness. It is because they are fixed to the speaker’s clothing, and remain unnaturally close and stationary.

FIGURE 10-4

Diagram indicating pick-up pattern differences between (1) shotgun, (2) cardioid, and (3) omni-directional microphones.

Imagine hitting a bunch of billiard balls and seeing one go into the intended pocket, while the others ricochet randomly off the cushions before slowing to rest. The sound made by a hand-clap behaves like this in a moderately sound-reflective space. It is the signal that ricochets off sound-reflective surfaces, which reflect reverberant sound as a mass of disorganized, decaying reflections that arrive at the ear (microphone) after differing degrees of delay. Echo on the other hand is the kind of crisply organized sound reflection that, after a short delay, returns your voice intact across a valley.

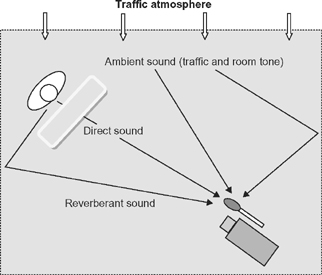

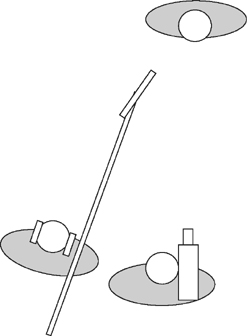

Figure 10-5 represents the sound components a sound recordist deals with while recording an interview situation next to a busy street. Ideal dialogue recordings have lots of signal (what you want) and very little “noise” (everything else).

Direct sound, also called signal, is that percentage of the speaker’s voice that travels direct to the microphone.

Reverberant sound is that which radiates outward and bounces off the floor, ceiling, walls, and table surface in front of the speaker before arriving at the mike fractionally later. By making longer journeys, reverb sound then combines with signal at the microphone to muddy the signal’s clarity. Once combined, signal and reverb are no more separable than the eggs in an omelet.

Ambient sound, or presence, is that which is native to the environment such as distant traffic, the hum of a refrigerator, a dog barking, or the whirr of air conditioning in summer.

Notice that sound in Figure 10-5 is being shot with a deck mike (one fixed to the camera), and is of necessity distant from the speaker. This has profound consequences on dialogue recording quality.

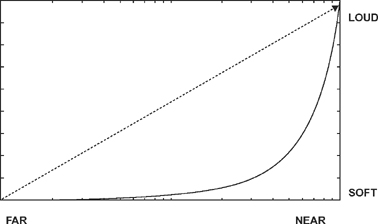

A nasty little secret awaits the rookie recordist: a sound’s amplitude (loudness) changes radically as you move a mike toward or away from its source. This is because sound, like light, decays over distance in a logarithmic, not linear fashion. The dotted line in Figure 10-6 is what most of us think is the loudness-to-distance relationship, but the curved solid line is the dismal actuality. As you see, the last few feet in mike-to-subject distance make a big difference to the amplitude (effective volume) of the recording. A sound recordist therefore must work hard to keep the mike close to the sound source, but out of frame.

FIGURE 10-5

Diagram representing a film interview and the three types of sound present in any recording situation: direct, reverberant, and ambient.

FIGURE 10-6

The dotted line is how one imagines a microphone behaving as you move it closer to a sound source, but the solid line—a logarithmic curve—is the actuality.

The sound recordist’s world has its dragons, but they can be tamed. By angling the axis of a directional mike at the speaker (as in Figure 10-5), one can lower some of the reverb and ambience, most of which arrives from off-axis directions. Importantly, one could move that mike much closer to the speaker. This barely changes ambience or reverb levels, but it produces a much higher signal level. An independently movable mike is thus essential, since any mike mounted on the camera,

● Is always at the camera’s distance and seldom proximate to the signal source.

● Only ever points along the camera-to-subject axis. New speakers in a discussion, for instance, will remain annoyingly off-mike until the camera turns to them.

● Is ideally situated to record the whine of the camera’s zoom and focus motors, and the bumping sound of your hands fumbling for the camera controls.

It is thus vital to position a mike closer using a boom or fishpole (Figure 10-7). We’ll look at boom handling techniques a little later. In a really noisy situation you would instead use a body mike, which also has its pros and cons. Remember that in postproduction you can always add atmosphere or reverb to a clean recording, but you can seldom subtract noise that is commingled with signal.

If you record a speaker in a large, sound insulated, carpeted room with heavy drapery over the windows, you will have an excellent signal-to-noise ratio because there’s a minimum of reverb and ambient noise. Now follow him when he walks into that tiled kitchen with the washing machine going, and you’ll have a dreadful S:N ratio and barely intelligible speech. Recordists therefore aim to,

● Choose the microphone with the best pickup pattern for the circumstances.

● Get a high ratio of signal-to-noise by placing each mike as close as practicable to its intended signal (the speaker/s).

● Procure on-mike sound by pointing the mike’s reception axis at the sound source and away from a source of noise.

These noble aims are often frustrated by documentary’s improvised nature. Imagine your difficulties when your main character chooses to confess what’s breaking his heart while working out in a noisy health club or driving his rattly old pickup truck. So much to go wrong!

Viewing a moving handheld shot, one can tell from the camera movements why the mike is moving in relation to the subject, and hear the sound quality change. However, in an edited sequence, the recordist has been forced to make mike position-changes in order to stay out of shot. Material may edit together beautifully for picture and narrative continuity, but each sound cut produces a distressingly obvious change in sound quality, level, and S:N ratio. True, you make adjustments in the speaker’s voice level from angle to angle, but that varies the admixture of ambience illogically at each sound cut. In postproduction you can reduce these disparities by adding ambience to the quieter tracks, but this is piling noise upon noise—all of which competes with signal.

Shooting sound will always be a series of compromises, so:

● Try to shoot in the quietest, least reverberant surroundings—seldom an option in observational documentary.

● Optimize S:N ratio by

● Choosing the right mike for the job.

● Placing the mike close to the signal source.

● Pan the directional mike so its axis always points at the signal source.

● Be ready to alter the scene axis during setup, if possible, so location noise comes from off-axis to the mike.

● Reduce reverb where possible by

● Making wise choices of location.

● Damping sound-reflective surfaces by laying carpet or blankets out of camera sight on hard surfaces such as the floor. To be fully effective on walls, these must hang several inches away from the offending wall, not be hard against it.

Professional mikes use balanced line cables, always recognizable from their sturdy XLR locking connectors, and noise-canceling three-wire connections (Figure 10-8). This allows long cable runs that are free of electrical interference pickup. Consumer equipment uses two-wire unbalanced sound connections identifiable by their two-contact jack plugs (Figure 10-9). Cable runs are restricted to a few feet, beyond which you should expect electrostatic interference.

Cables most often break down at the point where they enter a plug, so provide strain relief by anchoring cables to the body of their devices (Figure 10-10). This protects both plug and socket when inevitably someone trips on the cable. Mini-jack sockets are particularly vulnerable, especially those mounted direct on circuit boards. A single yank can do untold damage.

Using automatic sound-level spares you from overload distortion, but during long silences in an oral memoir, for example, the recording level will often “hunt.” That is, during silences it records ambience at ever-louder levels until your subject resumes speaking. This is because the circuitry is slavishly doing its job strictly according to sound input. Auto-level sound may also vary from one part of a scene to another, and the two edit together badly. So, unless you face a chaotic recording situation—soft sound punctuated by door slams and screaming revelers, say—help the editor by setting and maintaining audio levels manually.

FIGURE 10-9

Phone jack and mini-jack plugs. Two-connector unbalanced lines like these are vulnerable to hum and other electrical interference.

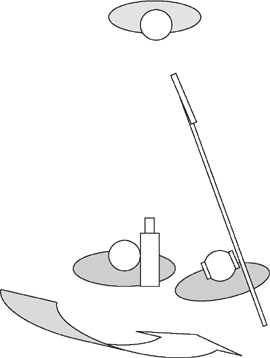

Aim to set one level in advance so you don’t have to ride gain (adjust volume) during a scene. First make a representative sound test to see how levels register on the volume units meter (averaging VU meter) or peak reading bar graph. Peaks should not exceed, say, –6 decibels (check camcorder recommendations). Be sure to test-record and play back loud transient sounds such as door slams, engine roaring sounds, or billiard ball impacts so you can pinpoint the level at which distortion sets in. When shooting mono sound, there is a neat way to use the camera’s second sound channel as a safety backup. See “Averaging and Peaking” below.

Note that VU meter scales run counter-intuitively (Figure 10-11). Low sound levels register as high minus decibel (dB) numbers, and then as amplitude rises, they diminish to the safe or sound saturation point of 0 dB. Unless the recorder literature says otherwise, VU meters are averaging meters: they have a slight lag as well as an insensitivity to transient peaks, a combination useful to the recordist because it approximates human perception of sound.

Digital sound recorded beyond 0 dB produces such spectacular distortion that the sound is often unusable. A trap awaits the unwary here, because unless your equipment has a peak reading facility, it is probably averaging incoming signals and masking the truth about extremes. A red LED light blinking on sound peaks usually signifies that peaks of unknown amplitude have already happened, leaving a raggedly distorted section.

FIGURE 10-10

Cable anchored to camera body to provide strain relief.

Guard against overloading (a) by setting averaging record levels to peak at –6 dB or so, and (b) as a safety backup, split a mono mike signal across the two stereo channels, setting Track 2 to record at a lower level. You can sometimes accomplish this using a microphone input box.

If you are using a consumer camera with a single mini-jack mike input, consider adding a proprietary input box. That shown in Figure 10-12 takes two mike inputs and can route each to a different channel, or spread a single mike’s output to both channels. The box’s output is via a stereo (three-connector) mini-plug on a short lead, which plugs into the camera’s mike input. Clamped under the camera body, the box and its beefy XLR sockets safely absorb cable-handling stresses, protect your camera, and let you adjust levels for two balanced-line microphones.

FIGURE 10-11

Typical stereo sound volume units (VU) meter layout. Camcorders usually allow you to see a moving bar-graph in the viewfinder.

FIGURE 10-12

Two-channel input box that can handle input from either microphone or amplifier (line). (Photo courtesy of Beach-TEK, Inc.)

Virtually all camcorders have stereo (two-track) recording capability. Not only can you record a mono mike with a lower-level safety backup (see in “Averaging and Peaking” above), but using a microphone input box or multichannel mixer your camcorder can record two entirely different mono inputs. These might be two people wearing lavalier (chest) microphones, or a mother and son phone conversation using a lavalier on the mom and a telephone attachment to pick up her son. Since they are on discrete tracks, you can adjust their relative levels later in the sound mix.

Film recording uses a variety of microphones made by a host of manufacturers such as Sennheiser, Schoeps, Audio Technica, and Shure. With microphones, as with hot dinners, you mostly get what you pay for. You get better or worse performance depending on your knowledge of mike strengths and weaknesses. A friend who teaches sound says, “There is no such thing as a bad microphone, only bad users."

Many mikes use an internal battery, so carry spares. Use only the alkaline variety, since they do not excrete a corrosive mess into the mike body after running down. Note that condenser microphones—particularly shotgun mikes—either run on inbuilt batteries, or draw current from phantom power supplied by some (but by no means all) cameras and a few input adapter boxes. Phantom power is 48 volts supplied at a tiny current to the mike through two legs of its three-wire cable. If a mike should mysteriously refuse to function, suspect it of needing phantom power.

Most important is to understand sound pickup patterns for several microphone types. The representation earlier of three different mike pickup patterns in Figure 10-4 indicated where you would have to place a noise emitter, if you circled around each type of mike with a tame cicada, to maintain an equal level recording.

The omni-directional mike is easy to understand: it picks up sound equally from all around, so you’d place your cicada at the same distance all around it. Other types of mike achieve good on-axis sound by discriminating against that which is off-axis. Here are some performance generalizations:

Omni-directional mikes give the most pleasing voice reproduction, but indiscriminately pick up unwanted sound reflected by surrounding surfaces.

Directional mikes (also called cardioids because of their heart-shaped pickup pattern) help reduce off-axis reverberant and background noise. In practical terms this means that pointing the mike’s axis at a speaker improves his S:N ratio. By the way, directional mikes intentionally have poor sensitivity at the rear end of the mike’s axis (Figure 10-13).

Hypercardioid or shotgun mikes (so-called owing to their shape and menacing appearance (Figure 10-14) do the best job of discrimination. During the Vietnam War a BBC news crew using a shotgun mike in the jungle was astonished to find it had taken a Viet Cong prisoner. A favorite in documentary and electronic newsgathering (ENG) work, the shotgun is especially practical in noisy situations. Its drawback is a slight loss of sound warmth and fidelity. More than most mikes, it needs astute handling so it stays out of shot, doesn’t cast shadows, and points at the right speaker in a group.

Lavalier, lapel, or body mikes are favored for interviews or speech recording in noisy surroundings (Figure 10-15). Participants wear these tiny, omni-directional mikes under upper clothing so they stay exceptionally close to the signal (speech) source. Place them under clothing out of sight, and at least a hand’s breadth away from a speaker’s chin, or sound levels will vary too much when the speaker’s head swivels. Clip the mike in place, anchoring its cord as in the photo, leaving a free loop under the mike as strain relief. Then if the cord is touched or yanked, handling noise or damage won’t reach the mike. You’ll need one lavalier per speaker, and a location mixer for multiple speakers (see Chapter 28: Advanced Location Sound). Lavaliers give lovely voice quality but are weirdly devoid of sound perspective. This is because movements toward and away from the camera remain in unnaturally constant relation to their sound source. We only hear our own voice with that kind of constancy.

FIGURE 10-14

Shure VP89S hypercardioid or shotgun mike, good for off-axis discrimination. (Photo courtesy of Shure, Inc.)

Lavaliers pick up clothing rustles and body movements—especially if the user wears man-made fibers. These generate thunderous static electricity noises. Warn participants to wear natural fibers, but if they forget, place adhesive tape between the mike and the offending surface. Lavaliers excel at amplifying loose dentures and the intestinal activity that follows dining.

Many larger mikes have small switches that allow you to roll off (attenuate, reduce) a particular band of frequencies. A “lo-cut” is commonest, and useful to reduce traffic rumble during street dialogue scenes. Many sound mixing boards have a low cut switch for each mike circuit.

Like mobile phones, radio mikes are wonderful when they work. Connect a lavalier mike to a personal radio transmitter, clip a small radio receiver to the camera, and hey presto, everyone has complete mobility. Alas, they have occasional dead spots. Be warned, too, that participants forget they are wearing them and may, without your intervention, broadcast their visit to the bathroom. A court used a recording made inadvertently by some of my students as evidence to indict a duplicitous police chief at a Native American demonstration.

A wired lavalier, though limiting to your subject’s mobility, is trouble-free compared with its wireless brethren. Hide the cable in the participant’s clothing so it emerges from a pants leg or skirt bottom. People usually forget they’re wearing them and walk away until they quite literally reach the end of their tether.

Breakdowns happen mostly where cables enter connectors, so carry spares. Mikes and mixers need batteries, so carry the right alkaline spares. A basic toolkit of solder, soldering iron, pliers, plain and Phillips-head screwdrivers, Q-tips, adjustable wrench, Allen keys, can of compressed air (for cleaning), flashlight, and an electrical multi-meter can often get you out of trouble in the field.

One shoots much location sound with a directional mike mounted on a fishpole and angled at the subject. Keep your hands in position: that is, don’t slide them or tap the pole, since handling noises reverberate through the pole to the mike. Be sure to monitor all sound you shoot through professional level, ear-enclosing headphones. Listen for sound quality, not meaning!

Position the mike above, below, or from either side of the frame. Miking from above is preferable because a voice will be louder than the speaker’s footsteps and body movements. Should the fishpole cause shadow problems, try coming in from the side of the frame. When all else fails, point the mike upwards from below frame, remembering that this may privilege footsteps and body movements over voice levels.

FIGURE 10-17

The camera shoots a reaction shot while the mike covers an off-camera speaker. In every-day life, our eyes and ears often unconsciously separate like this.

When working alone, you can minimize camera handling noises by mounting a separate mike in a flexible cradle called a shock mount on the camera body. This helps minimize camera handling sounds traveling via conduction to the mike. Figure 10-16 shows a common rubber-band model on the left, but the right-hand design works better.

You are always better off with the mike handled by someone operating a fishpole (Figure 10-17). It means that an autonomous mike is independently seeking the best sound, wherever that might be in relation to the camera.

Shield the mike from air current interference, even indoors, with a windscreen (Figure 10-18). This is a rigid zeppelin wind guard, with a fuzzy fur miniscreen, or windsock added to defeat larger volumes of air movement (Figure 10-19). Without such shielding, air currents shake the mike’s diaphragm and produce earthquake quantities of wind rumble.

Frequently the sound source originates in the camera frame but then moves elsewhere. In a group scene, for instance, the camera may dwell on someone’s telling reaction long after someone new starts speaking. The mike cannot stay with the (now silent) camera subject but must turn immediately toward the new sound subject, as diagrammed earlier in Figure 10-17. Novice sound recordists have to train themselves to prioritize listening above looking—quite counter-intuitive at first.

Getting on-mike sound without causing shadows takes close coordination between recordist, camera operator, and director. Miking from a safe distance is never an option because signal-to-noise ratios and voice quality decline so precipitously. The goal is to position the mike as close as possible, and pointed at each new speaker, while staying just out of frame. Handheld sequences are always the most challenging because the mike must not edge into the frame. Usually the recordist stands a little ahead and to the left of the camera, staying in the camera operator’s left-eye sightline (Figure 10-20). Experienced, on-the-ball recordists constantly glance between the subject, the likely edge of frame, and the camera operator for telling facial expressions or hand signals. These might signify, “Watch out, I’m going to swing in your direction,” or the more agitated “Back off—mike’s edging into frame.” Staying close to moving participants’ sound axes, yet keeping the mike from drifting into frame, requires the recordist to guess who, between camera and participants, will move next, and what direction they may take.

FIGURE 10-19

Fuzzy fur miniscreen or windsock covering zeppelin guard. (Photo courtesy ofK-TEK.)

Sometimes the operator makes a hand signal to warn of a coming pan to the left, or of intending to back away for a wide shot. The recordist may lift the mike over the camera and cross the shooting axis behind the camera in order to position the mike temporarily over the camera from the right (Figure 10-21).

In a two-person crew when the camera starts to track backward, the recordist or the director will lightly touch the operator’s back with a free hand to signal, “I’m here and I’m watching for your safety.” This touch includes gentle steering—gentle because over-zealous handling would rock the camera. The aim is to help the camera operator go in reverse, clearing kerbs, doorways, or furniture without looking backward.

It’s quite marvelous to watch the precision and confidence with which an experienced crew negotiates such obstacles. The ultimate challenge to the mobile documentary unit is a rapidly moving subject who whirls through a street market then jumps into a taxi, all the while chatting to the camera. Keeping all this nicely framed on the screen, and with no sign of the unit’s frantic adaptations, will stretch a crew to its limits, particularly when two people silently cram themselves and their equipment around a surprised taxi driver. With experience, crews learn to work in perfect balletic harmony—and even to exchange hand or eye signals during the take. It’s a joy to watch.

FIGURE 10-20

Typical sound recordist’s positioning during mobile shooting.

Every shooting situation comes with problems, of which you take careful note while scouting the location. Overhead wires can turn into aeolian harps, dogs bark maniacally, garbage trucks mysteriously convene for bottle crushing competitions, and somebody starts practicing scales on the trumpet. The astute location spotter can only anticipate some of these sonic disasters.

While the camera is running, close all doors and windows to block exterior sounds, no matter how hot the room. Also temporarily disable anything liable to run intermittently like air conditioning or a refrigerator. Leave your car keys with any appliance you must remember to switch back on.

FIGURE 10-21

The recordist must sometimes cross behind the camera, mike still in place, to angle in from the right of frame. The camera now blocks eyeline exchanges with the camera operator.

Ambient sound is most noticeable during relative silences, but each location, and each mike position within that location, has its own characteristic “presence.” One may not cut well with another. In each case, choice of mike, the axis of directional mikes, and getting the mike in close to the desired signal all help toward consistency.

During takes, the crew and any onlookers must be stationary and silent, and the camera must make no sound that the mike can pick up. Fluorescents like to buzz, filament lamps can hum, and pets come joyously to life at inopportune moments. Mike cables placed in parallel with power cables may produce electrical interference through induction, and sometimes very long mike cables pull in cheery DJ’s via radio frequency (RF) interference. Elevator equipment can generate alternating current magnetic fields, and the most mysterious hum sometimes proves to come from something on the floor above or below. Every situation has some degree of remedy once you have located the cause.

Before calling for a wrap at any location, whether interior or exterior, let the crew record a presence track (also known as atmosphere, room tone, or buzz track). Do this in every location, every shooting day, because each occasion has its own changing ambience. The procedure is simple. The recordist,

● Calls “Everyone freeze for a presence track!” and everyone stands silent.

● Records ambient sound, using the current mike position.

● Calls “Cut,” when everyone jumps into action, wrapping up that location’s equipment ready for the next.

The 2 minutes of presence recorded on the set, duplicated if necessary, becomes the vital filler for any dead spaces in edited dialogue tracks. These might occur when, for example, you use a cutaway that was shot silent, or remove an off-camera expletive. Because postproduction can only add, never remove, background atmosphere in dialogue tracks, the editor must work to make every angle’s background sound consistent. Tracks with quiet presence must match those in the angle having the loudest, if all angles are to end up with the same ambience.

Watching a finished film, the audience expects each new sequence to sound as it does in life. The ear identifies its nature, then screens it out while concentrating on the foreground signal. This natural adaptation fails, however, when irritating and intrusive changes in “atmos” occur from angle to angle. To cure this, background atmospheres and presence tracks must be added and level-adjusted to create a seamless auditory experience. This is our experience of ambience in life—so we expect no less in films.

Any voice or atmosphere track shot asynchronously and independent of picture is called a wild track. When a participant flubs a sentence, or some extraneous sound intrudes on dialogue, the alert sound recordist asks to make a wild, voice-only recording immediately after the director calls “Cut.” The participant repeats the previous words just as he or she spoke them during the take. Because it’s recorded in the same acoustic situation, the words can be seamlessly edited in. Be sure to verbally identify the section of wild track, so the editor can locate it.

A non-synchronous recording of a sound useful to a sequence’s sound track is called an effects (FX) or atmosphere track. The recordist might carry a small recorder to get tracks of that early-morning rooster, or distant church bells to help create a composite atmosphere. In a woodland location this might include daybreak bird calls, river sounds of water gurgling, ducks dabbling, and wind rustling in reeds. A woodpecker echoing evocatively through the trees is probably best found in a wildlife library, since getting near them is hard and background noise normally is too high. A sound recordist needs initiative, imagination, and a naturalist’s tolerance for frustration.

Films often provide sound that liberates the imagination rather than sound literally present in the location. To be true in spirit, you might wholly construct a soundscape in postproduction. At the exquisite nature center near my home in Chicago there are deer, wild flowers, some prairie, a lake with a heron or two, and lots of wild birds. I have daydreamed about filming a yearlong cycle of life there, but vehicles roar past only two blocks away, and it’s under the flight path of the world’s busiest airport. I would need to reconstruct every atmosphere and sync sound because no audience could concentrate on lyrically backlit meadow grasses to the ominous whine of sinking jetliners.

An interesting exercise is to make a sound montage that tells a story without any narrating. You might, for instance, make a short montage of your morning, telling it through the characteristic sounds of each phase. Do you have pets at home? See what you can do with the different ambiences and spaces. Shoot music where it is part of the natural circumstances (listening to the radio for the news to begin, for instance). This is a good subject to observe and take notes before you shoot sound. There is no special project for this, but perhaps there should be!

1. Previously I credited this saying to Robert Bresson, only to discover after rereading his Notes on Cinematography (Urizen Books, 1977) that it was my summation of his ideas, not his words.