This Part considers lenses in relation to the perceptions of space and perspective, which together do so much to shape the look and impact of photography. There is information on the principles governing the use of advanced camera and sound gear, but equipment that is more elaborate normally means you will be directing specialists rather than handling it yourself. Nonetheless, you need to know what they will be doing and why.

There is information about the extra personnel you need in a larger unit, and tips on leadership. Because a director must know how to catalyze telling scenes for the screen, there is a comparison between acting and being a documentary participant. There is also guidance on coverage and shooting with editing in mind, and, most importantly, a long chapter on interviewing—that vital key to opening people to the audience.

Properly used, lenses complement your way of seeing. They do however take some basic understanding, for though a camera lens functions like that in the human eye, the shortcomings of camera technology require you to make various adaptations. No art form is without its compromises, and all require the art that hides art. Painters, after all, have to render a three-dimensional world on a two-dimensional canvas. Likewise, camera and lens compromises result from most cameras recording in two dimensions instead of three, and from their field of vision being rather limited compared with that of the human eye. We compensate for this by arranging composition and lighting to create the illusion of depth, and cramming more than normal into screen space and screen time.

The eye of the beholder is misleading, for the field of view (FOV) of the human eye is huge—approximately 160° horizontally, and 75° vertically (Figure 26-1). Try it for yourself by stretching your arms ahead, wiggling your thumbs, then gradually stretching your arms sideways. You should still see your thumbs moving even though your arms are wide apart. No equivalency to this exists in camera optics: to replicate a human-eye sense of perspective in DSLR 35 mm photography you would use a 50 mm (standard) lens with a FOV of only 40° width and 27° height.

The significance is that even a wide-angle lens may cover less than a quarter of the eye’s intake, with resounding consequences for dramatic composition. We therefore rearrange compositions to trick the spectator into seeing the eye’s sensation of normal compositions, distances, and spatial relationships. Characters holding a conversation might stand closer than usual before the camera, yet pass as normally spaced onscreen; furniture placement and distances between objects are often cheated, that is, moved apart or together to produce the desired appearance onscreen. Even physical movements need adjustment: someone walking past camera or picking up a glass of milk in close-up may have to carry out these actions one-third slower if it’s to look natural onscreen.

Packing the frame, creating the illusion of depth, and arranging for balance and thematic significance in each composition are all routine compensations for the 2D screen’s limited size and tendency to flatten space.

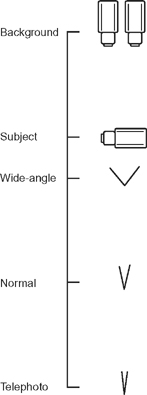

We assess distances by comparing the size of things—say, a cat in the foreground and a sheepdog around 10 feet away in the background. Knowing their relative sizes lets us judge their distance apart. Figure 26-2, shot with a “normal” lens, allows you to make an accurate judgment of their distance apart by their relative sizes. Lenses other than normal alter this perception, and are classified as either wide angle or telephoto. Analogies from everyday life illustrate the differences:

| Wide-angle lens | Normal lens | Telephoto lens |

| Door security spyglass (diminishes sizes, exaggerates foreground size in relation to background) | The human eye (renders perspective—foreground sizes relative to background sizes—as we consider normal) | Telescope (magnifies, brings everything closer, but compresses foreground and background together) |

The same shot taken with a wide-angle lens (Figure 26-3) changes the apparent distance between foreground and background, making it appear greater. The telephoto lens (Figure 26-4) does just the opposite, squeezing foreground and background planes close together. If someone were to walk from the background truck up to the foreground, the implications of their walk would be dramatically different in the three shots; all would have the same subject, all walks would last the same time, yet each lens would convey a different dramatic “feel.”

FIGURE 26-3

Wide-angle lens.

Using the magnifying or diminishing effect of different lenses allows us to produce three similar shots with very different feeling. By placing the camera differently (see Figure 26-5, Figure 26-6, and Figure 26-7) camera-to-subject distance changes, and with it, perspective too. Wide-angle lenses appear to increase distance; telephoto lenses appear to compress it.

FIGURE 26-4

Telephoto lens where the foreground to background distances appear different from those in Figures 26-2 and 26-3.

Lenses are described by their focal length rating, which is the measurement in millimeters from the lens optical center to the film plane. Cameras have very different image receptors (such as 35 mm film, or ½ and ⅔ inch video), and each requires a certain degree of refraction. Thus to reproduce the look of normal perspective, each will need a focal length lens calculated for the image receptor size (see “Depth of Field” below).

By repositioning the camera and using different lenses, as shown diagrammatically in Figure 26-5, we can standardize the size of the foreground truck, as seen in Figure 26-2, Figure 26-3, and Figure 26-4. Though foreground-to-background distances appear to have changed, the perspective changes we see result from changing the camera-to-subject distance, not from using different lenses.

FIGURE 26-5

Different lenses from different distances in Figures 26-2, 26-3, and 26-4 produced the same size foreground truck but altered the apparent distance to its background. Perspective changes only when you alter the camera to subject distance, not because you change lenses.

To prove this, examine Figures 26-6, Figure 26-7, and Figure 26-8. Each shot is taken from the same camera position using a different lens, but in all three the proportion of the stop sign remains the same size in relation to the background portico. Perspective—size proportions between planes—has not changed, we simply have three different magnifications.

A lens change alone will alter the audience’s sense of distances, but won’t affect actual perspectives. The axiom is that you can only change perspective by changing the camera-to-subject distance. Changing lenses from a fixed camera position only enlarges or diminishes a given perspective, and shrinks or magnifies the apparent distances.

Compare Figures 26-6 and Figure 26-8. The backgrounds are very different in texture. The subject is in focus in both, but the telephoto version puts much of the image in soft focus, isolating and separating the subject from both foreground and background. This happens because the telephoto lens has a very limited depth of field (DOF’. Its point of focus alone is truly sharp. Conversely, a wide-angle lens (Figure 26-3 and Figure 26-6) allows deep focus, useful if you want to hold someone in focus while he is walking between foreground and background. Deep focus may however drown its middle-ground subject in a plethora of irrelevantly sharp background and foreground detail. Isolating the subject by focus, rather than by lighting or framing alone, can be dramatically useful.

FIGURE 26-7

Normal lens.

FIGURE 26-8

Telephoto lens. This shot and Figures 26-6 and 26-7 are taken from a common camera position. Notice that the stop sign remains in the same proportion to its background throughout.

This deceptive term concerns a lens’s ability to transmit light and has nothing to do with movement. A fast lens transmits much light, making it good for photography in a low-light situation while a slow lens transmits less light but may do so because it is a telephoto and has other advantages. Wide-angle lenses, by their inherent design, tend to be fast (with a widest aperture, say, of f1.4’ while telephotos tend to be slow (perhaps f2.8’. A wide-angle with a two-stop advantage might need only one-quarter the light of a telephoto, and so make night shooting viable.

Prime (that is, fixed’ lenses, having few lens elements, tend to be faster than zooms, which are multi-element. Primes also have better acuity, because the image passes through fewer lens elements. The state-of-the-art RED modular digital camera (Figure 26-9, www.red.com) uses 35 mm prime or zoom lenses, and behaves like the feature film camera it really is, but with none of the bulk.

A zoom is a lens that is infinitely variable between its focal length extremes. A zoom of 10 to 100 mm focal length is said to have a ratio of 10:1, which means that zooming in on a subject magnifies it tenfold. As we have said, the proportion of foreground objects relative to their background does not alter. To produce a similar magnification with a fixed lens you would use a dolly movement (physically moving a camera toward the subject on a wheeled base’. Here not only the size of the image is increased (due to closer camera-to-subject proximity’ but you see a continuous perspective change during the movement. This reproduces the natural perspective changes our eye sees when we move around.

Summing up, dollying gives movement with a perspective change, while zooming gives optical magnification without a change in perspective.

FIGURE 26-9

The RED modular camera fully equipped for handholding. (Photo by courtesy of Red Digital Cinema.’

Until recently film stocks and video used to yield markedly different image aesthetics. As cameras have become more sophisticated it is increasingly difficult to identify the recording medium from the screen results. The latest postproduction software also gives a high degree of control over contrast, gamma (black levels’, and color hue and saturation (color intensity’. Differences between film and video images may show in other ways, however. In a 35 mm DSLR camera close-up of a man in a park, his face will be in sharp focus but the foliage in the background and foreground is agreeably soft-focus. The same close-up taken with a consumer video camera may have foreground, middle-ground, and background all in similar degrees of focus, subjecting the eye to a deluge of irrelevant detail. Why?

At the root of these differences is lens depth of field (DOF’. The 35 mm DSLR camera image receptor has a larger area than many video imaging chips. The larger the image size, the greater the refraction (bending of light’ by the lens, with the net result that there is less DOF. That is, less is acceptably in focus behind and in front of the plane of focus. A Victorian plate camera has a huge imaging area, and consequently DOF is so shallow that a portrait’s eyes may be sharp while the tip of his nose is out of focus! Compare this with a family video camera, with its tiny ¼ inch chip image area: image refraction is so minimal that in daylight, hardly anything is ever out of focus.

The optics of the larger format cameras, such as those in the Canon EOS line of DSLR cameras, allow you to isolate a given plane in focus and throw other planes into soft-focus (Figure 26-10). With a small-format camera you can achieve this effect only by using a telephoto lens, which means shooting off a tripod for steadiness. Another strategy is to open the f-stop wider to use a larger area of the lens. This increases the amount of lens refraction, giving a shallower DOF. Also affecting depth of field is distance from camera: close subjects have less depth of field than distant ones.

Summing up, the four variables that affect depth of field are,

1. Imaging sensor size (small = deep DOF, large = shallow DOF’

2. Lens aperture size (closed = deep DOF, open = shallow DOF’

3. Lens focal length (short = deep DOF, long = shallow DOF’

4. Focus point (close = shallow DOF, far = deep DOF’

In Chapter 12: Camera, “Composing the Shot,” we considered the dynamics of operating in synchronicity with life as it unfolds and the basics of framing, including the Rule of Thirds. As a Storyteller, you aspire to inflect your camerawork with a spectrum of attitudes and ways of seeing—an authorial demand not easy to sustain when you are struggling to keep up with events. How well you and your camera operator function depends on three considerations.

● How thoroughly have you, as director, considered where you stand in relation to what you are about to film?

● How well have you prepared the camera operator in relation to your thinking?

● How well grounded is the operator in compositional principles?

FIGURE 26-10

Selective focus places attention on the woman among these birdwatchers.

Composing images is a fascinating business. It revolves around the human eye’s natural, inbuilt preferences and responses, and the way the eye suggests ideas and feelings to the mind. In return, the mind responds symbiotically by finding further proof in what the eye sees. This complements the expectations we have held all along for documentary—that there are meanings and designs in life for you to find and propagate. You have great latitude for artistry since there are multiple vantage points in most situations, and many ways to your audience’s responses through framing, lighting, juxtaposition with background and foreground elements, and so on.

The visual composition that goes into form (which is how you present content’ is more than embellishment; it is a force for communication. Form can interest and even delight the eye, but in purposeful hands it becomes an organizing force that dramatizes relationships and germinates ideas (Figure 26-11). As such, it makes the subject (or “content”’ accessible, heightens the viewer’s perceptions, and stimulates critical involvement. The way most cinematographers study composition is through painting, a medium in which images are constructed with great deliberation.

A good way to discover the natural sensitivity and preferences of the human eye—yours and an audience’s—involves making up a short slide display and exploring it with a few friends. Download 10–20 images of varied but striking design from a source like Google Images. Suggested artists:

(Painters’ Mary Cassatt; Honoré Daumier; El Greco; Wassily Kandinsky; L.S. Lowry; Berthe Morisot; Edvard Munch; Alfred Sisley.

(Photographers’ Ansell Adams; Diane Arbus; Henri Cartier-Bresson; Josef Koudelka; Vivian Maier, László Moholy-Nagy; Sebastião Salgado; Edward Weston.

Assemble your slideshow in random order, then show each picture for under 10 seconds. Avoid contemplating what story the picture tells, if any, but instead take turns to trace on the screen how your eye traveled around the picture from the moment of first seeing it. The aim is to reconstitute how your eye worked, what you noticed, and what you thought along the way. For the full exercise, see the picture analysis project at www.directingthedocumentary.com.

Typical thoughts:

● What made my eye go to its particular starting point in the image? Was it the brightest point; the darkest; an arresting color; a human face or a significant junction of lines creating a focal point? Something else?

● What moved my eye away from its point of first attraction, and what drew it onward to each new place?

● If I trace out the route my eye took, what shape do I have? A circular pattern; a triangle or ellipse; what else?

● How do I classify this compositional movement? Is it geometrical, repetitive textures, swirling, falling inwards, symmetrically divided down the middle, flowing diagonally…?

● Are places along my eye’s route charged with special energy? Often these are sightlines, such as between two field workers, one of whom is facing away.

● How are the individuality and mood of the human subjects expressed? By making juxtapositions between person and person, person and surroundings, body language, facial expression?

● How much movement did my eye make before returning to its starting point?

Visual design is an immensely complex business, and its rules and guidelines are not easy to understand, particularly from a book. Here are some initial categories and associations for you to consider, but your camera-operating will profit from a full study of compositional values if your eye and mind are to be ready. Camera operating also requires the operator to respond from a dramatic awareness. He or she should see in terms of relatedness and constantly use composition and juxtaposition to further the differing moods and dramatic potential of the filming. Table 26-1 features some of the elements and their associations that a trained eye will see.

The camera operator, particularly in improvisational situations, composes so that the audience sees and feels in particular ways. He or she must rapidly see, adapt to, and exploit the compositional potential of each new situation. The operator must take decisions in real time about framing, camera vantage, or movement while occupying the double role of audience and creator. He or she relies on intuition, knowledge of your story and its intentions, and compositional and dramaturgical values so internalized that he or she recognizes them as opportunities take shape. Very few camera operators rise to these heights of self-education and intuition.

The film spectator must interpret each shot within its given time. This is like reading an advertisement on a passing bus; if you don’t get the words and images in the given time, the bus drives on leaving the message unabsorbed. If however the bus crawls past in traffic, you see its message to excess and may become bored and rejecting.

The analogy suggests there is an optimum duration for each shot, which you judge according to its content, meaning, and complexity (Figure 26-12). How much time the audience gets to “read” the shot depends not only on its content, but also on the cutting pace of those preceding. The innate principle the editor uses to determine each shot’s duration—by content, form, and audience expectation—is called visual rhythm. The pace can be relaxed or intensified according to how you want to develop the audience’s relationship to the film.

A balanced composition can become disturbingly unbalanced if someone moves or leaves the frame. Even a movement by someone’s head in the foreground may posit a new sightline and a new scene axis, and thus demand a compositional rebalance. This might involve not only reframing, but moving the camera to a new vantage point. A zoom into close shot usually demands reframing, for though the subject remains the same, the compositional content changes, sometimes drastically.

When you operate a camera, you might need to,

● Reframe because the subject moved. Wait to see if they move back or whether you should reframe.

● Reframe because something/someone left the frame. Will they/it return?

● Reframe in anticipation of something/someone entering the frame. You hear steps approaching a door, and reframe to anticipate the door opening.

● Change the point of focus to move the attention from the background to foreground or vice versa. This changes the texture of significant areas of the composition.

● Move within an otherwise static composition. Any camera movement (across subject, diagonally, from the background to foreground, from the foreground to background, up frame, down frame’ benefits from a motivation, either authorial, or by movement within the frame, such as a car passing or a character whose state of mind calls for closer study.

● Decide who or what you feel close to. This concerns point of view and is tricky, but, in general, the nearer one is to the axis of a movement, the more subjective one’s sense of involvement, and the farther you are from the axis, the more objective, sociological, or historic is the viewpoint.

● Decide how to adjust to a figure who moves to another place in frame. Ideally subject movement and the camera’s compositional change are synchronous, as they are in fiction films. In documentary, the camera move looks logical if it lags a little behind the movement, but inept if it anticipates it.

● Decide how to angle composition in relation to sightlines. Should you get close to their axis, or should you let them extend across the screen. Altering from one to the other often marks a shift between subjective and more objective points of view, or vice versa. Properly calculated, this can come as a relief or a welcome intensification.

● Decide what a change of angle, or of composition, would make you feel toward the characters. Maybe more or less involved, or more or less objective?

● Look for a composition that more forcefully suggests depth. In 2D photography this is the missing dimension that constantly needs reinforcing. Action taking place across the screen flattens space, while action that takes place in the screen’s depth extends it.

● Compose to include background detail that comments on, or counterpoints, foreground subject. The aware camera operator sees dramatic ironies and tensions inherent in visual components, and consciously juxtaposes them.

Beyond internal composition, that is, composition internal to each shot, there is external composition. This is the compositional relationship at cutting points between an outgoing image and the next or incoming shot. Seldom do we notice how much it influences our judgments and expectations. Take a favorite film and use your slow-scan facility to help you assess compositional relationships at cutting points. Find aspects of internal and external composition by asking,

FIGURE 26-13

Using the Rule of Thirds in composing helps the eye decide meaning efficiently.

● Where was your point of concentration at the end of the shot? Trace where your eye travels through the shot with your finger on the monitor’s face. Its last point as the shot ends is where the eye enters the incoming shot composition. Interestingly, the length of a shot determines how far the eye gets in exploring it—so shot length influences external composition.

● Are complementary shots symmetrical? Some shots—two people facing each other for instance, with lead space for each—should be complementary (designed to intercut’ and their compositions should reflect this.

● What is the relationship between two same-subject but different-sized shots that are designed to cut together? This is revealing; the inexperienced camera operator often produces medium and close shots that cut together poorly because proportions and compositional placing of the subject are incompatible. The Rule of Thirds can help you stay compositionally consistent (Figure 26-13).

● Does a match cut, run very slowly, show several frames of overlap in its action? Especially in fast action, a match cut (one made between two different size images during a strong action’ needs two or three frames of the action repeated in the incoming shot to look smooth, because the eye does not register the first two or three frames of any new image. Think of this as accommodating a built-in perceptual lag. The only way to cut on the beat of music is thus to place all cuts two or three frames in advance of the literal beat point.

● Do external compositions make a juxtapositional comment? Examples: cutting from a pair of eyes to car headlights approaching at night; cutting from a dockside crane to a man feeding birds, arm outstretched.