I do not avoid sacrifice. I do not refuse the sacrifice of myself. However, I cannot tolerate the reduction of the self to nothingness in the process. I cannot approve it. Martyrdom or sacrifice must be done at the height of self-realization. Sacrifice at the end of self-annihilation, the dissolving of the self to nothingness, has no meaning whatsoever.1

Those who suffer from a power complex find the mechanization of man a simple way to realize their ambitions. I say, that this easy path to power is in fact . . . a rejection of everything that I consider to be of moral worth in the human race.2

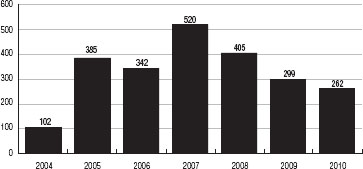

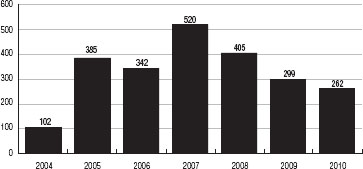

The annual number of suicide bombings peaked in 2007 at 520. After that, they decreased, to 405 in 2008, 299 in 2009, and 262 in 2010 (see Figure C.1).3 Although this decline is a welcome trend, one should take into consideration that the number of attacks in 2010 exceeded the total number of attacks for every year prior to 2005. Thus, while suicide bombings have decreased significantly in a relative sense, in an absolute sense the numbers of attacks, fatalities, and injuries remained high in 2010.

The tactical effectiveness of suicide bombing continues to vary significantly depending on the quality and experience of the support networks behind individual bombers. For example, on December 11, 2010, Taimour Abdalwahhab al-Abdaly, a twenty-eight-year-old man of Iraqi descent, attempted a suicide attack in Stockholm, but managed to take only his own life. He seems to have originally become radicalized online. He then traveled to Iraq, where he became radicalized even more and received some training in explosives manufacture. He almost certainly received assistance in Stockholm from a couple of accomplices but was not part of a well-established organization, which contributed to the amateurish quality of his bomb and attack.4 Abdaly’s mission highlights two of the overall trends that have characterized the suicide bombing of global jihadis in recent years. First, electronic communication continues to give the movement a long reach by introducing like-minded individuals in geographically dispersed areas to jihad and the possibility of pursuing it. Second, effective attacks require organizations with specialized training and experience because suicide bombing is not easy to carry out.

FIGURE C.1Suicide Attacks Worldwide, 2004–2010

Source: Worldwide Incidents Tracking System, National Counterterrorism Center, wits.nctc.gov (accessed April 1, 2011).

When a well-run support network exists, suicide attacks continue to be devastating. As of early 2011, indiscriminate mass-fatality attacks against civilians were still a regular occurrence. At the same time, analysis of specific attacks revealed that suicide bombing is most dangerous when militants use it precisely rather than indiscriminately, as shown by an attack on a CIA base near Khost, Afghanistan, on December 30, 2009. On that day, Humam Khalil abu Mulai al-Balawi, a physician born in the Jordanian town of Zarqa, was able to infiltrate the base and access a meeting of CIA intelligence officers from the area. When he detonated his explosives, he killed not only himself but eight experienced agents—five from the CIA, two from the private security firm Xe (formerly Blackwater), and one from the Jordanian army who also happened to be a cousin of Jordan’s King Abdullah. The attack devastated U.S. human intelligence efforts to an extent not seen since the 1983 bombing of the U.S. embassy in Beirut.5

Al-Balawi’s attack demonstrates the effectiveness of a truly intelligent bomb—effectiveness that largely had been lacking among Afghanistan’s suicide attackers. He was apparently a double agent, originally a jihobbyist who in the online world went by the name of Abu Dujanna al-Khurasani.6 The CIA recruited him to provide information on the whereabouts of key figures, such as Ayman al-Zawahiri. Over a period of several months, he appears to have produced enough information to build trust and a rapport with his handlers so that when he requested a meeting, he was not physically searched, which allowed him to access so many intelligence agents while wearing a suicide belt.

The transformation of martyrdom from an unpredictable event into a systematic organizational control mechanism was the primary innovation making suicide bombing possible. It has also been the most challenging element of suicide bombing to manage in practice. One of the most apparent trends emerging from a close examination of suicide bombing as a historical phenomenon is the tension between its strategic value, a consequence of its association with classical martyrdom, and its tactical utility, a consequence of the use of human beings as guidance systems by other humans. Authenticity is the key to the successful management of this tension.

The case of the hunger strike by Irish republican prisoners in 1981 demonstrates the importance of freedom and self-realization on the part of the individual for self-sacrifice to be understood as being authentic by a community. Even though it cannot be known definitively, the public perception of this internal dimension of martyrdom ultimately matters. When leadership loses the position of moral certainty, the use of suicidal volunteers for any purpose can backfire.

Leaders of the global jihadi movement have sought to convince Muslims around the world that their suicide attackers are indeed martyrs making the ultimate sacrifice for the faith and its followers. They have been unsuccessful in achieving this aim, largely because their ideology places them in a difficult position, or as Vahid Brown describes it, a “double bind.” The group asks its followers to abandon specific local grievances for the purpose of pursuing global jihad. It legitimizes this reorientation by developing a radically new religious framework that differs not only from that of mainstream political Islam, but also from jihad as understood by Islamists for decades. The group and its leaders, however, lack the religious credentials necessary to convince all but a minority of radicals that this reorientation of strategy and redefinition of jihad is in fact legitimate. Consequently the movement has failed on both levels: it remains an outsider in significant local conflicts, such as the Israeli-Palestinian struggle, and it cannot compete with other violent Islamists in terms of religious credibility.7

The jihadi double bind prevents the movement from convincing local communities and their leaders that jihadi suicide bombers are in fact dying on behalf of their communities. It also prevents the movement from justifying the attacks in terms of Islam more generally. In such an instance, the organizational element, in this case the jihadi leaders, cannot disguise the fact that it is driving the violence, not the community’s needs. Instead, most audiences globally seem to understand that jihadi suicide bombers are driven by individual motivations and their organizational culture. Their violence is therefore perceived as being self-motivated and their deaths sequential acts of suicide rather than legitimate acts of martyrdom.

The globalization of suicide bombing in the early 2000s, and its subsequent identification with the global jihadi movement, ironically may have begun to de-legitimize suicide bombing as a form of Islamic resistance in the eyes of local groups, for a striking characteristic of suicide bombing by the late 2000s was the almost complete absence of the type of localized suicide bombing carried out by groups like Hizballah, Hamas, and the Tamil Tigers in the 1980s and 1990s. The LTTE, as noted earlier, conducted several attacks in the years before its defeat in 2009, but other groups with a strong local presence—that is, Hamas and Hizballah—chose not to deploy suicide attackers during this time despite full-scale warfare with Israel.

Chapter 6 reveals how the Israeli response to Palestinian suicide bombing and the changed political relationship between Hamas and Fatah led to the virtual cessation of suicide bombing after 2005. There is a third, cultural factor that also warrants mention: the negative influence of the global jihadis and their particular culture of martyrdom on the Palestinian scene. With the exception of a few small groups, global jihadism has not put down roots in the Palestinian territories. Hamas leaders have contributed to this situation by suppressing jihadi supporters when they have emerged, but also significant is the lack of appeal that the jihadi program holds for most Palestinians. Jihadi leaders, including Zawahiri, have condemned Hamas for being insufficiently Islamic, for participating in secular elections, and for failing to implement Islamic law in the territory it controls. The jihadis have demonstrated no appreciation for the reality of the Palestinian political situation and instead encourage an abstract and absolute form of political Islam that most Palestinians reject. Therefore, even if Hamas’ leaders were inclined to associate with the jihadis, such a connection might discredit them in the eyes of their Palestinian followers.8

It is possible that overuse and commodification of jihadi suicide bombers on the global level created a degree of popular disdain for the jihadis’ campaign that may have devalued the symbolic power of Palestinian suicide bombers specifically and suicide bombing more generally. For example, in 2009 the Egyptian-born Islamist Abu Walid al-Masri, who had fought against the Soviets in Afghanistan and befriended Osama bin Laden, condemned al Qaeda’s ideology, singling out suicide bombing for particular attention. He argued that al Qaeda’s reliance on suicide attackers sent the wrong message—that is, that al Qaeda had a surplus of fighters and was trying to get rid of them instead of valuing them. He suggested that al Qaeda had so befouled the image of holy war that the wisest move for the Taliban would be to dissociate itself completely from the al Qaeda core.9

Hizballah has not claimed any suicide attackers since 1999 despite a major war with Israel in 2006. There is, however, evidence that the group used at least one suicide bomber in a spectacular operation during this period, but has been unwilling to claim the attack. On February 14, 2005, former Lebanese prime minister Rafik Hariri was assassinated by a massive bomb while traveling in an armored motorcade in Beirut. Physical evidence and eyewitness testimony both suggest that a suicide bomber in a white van was responsible for the blast. Hariri was traveling in a convoy of five vehicles that included trained guards and utilized sophisticated electronic countermeasures to foil roadside bombs specifically. A suicide bomber was probably the only practical way of reaching him, proving again that a well-trained and supported suicide bomber is among the most effective weapons in the world today. Hariri was the most important politician in Lebanon, making his death the most politically significant suicide attack there since the major bombings of 1983.

Suspicion immediately fell upon Hizballah. In summer 2011 the United Nations Special Tribunal for Lebanon, the body charged with investigating the assassination, officially indicted four members of Hizballah, charging them with involvement in Hariri’s death. Hizballah had opposed the tribunal and continues to deny any connection to the assassination.10

If the UN tribunal is correct, Hizballah has good reason to deny responsibility for using one of its “self-martyrs” against one of the most popular politicians in Lebanon. Since the group’s founding, Hizballah’s martyrs—with suicide bombers the most revered among them—have continued to dominate its public discourse and to legitimize it as a resistance organization.11 The organization, however, can derive legitimacy from its martyrs only if they are seen as heroic by the community and only if Hizballah is seen as respecting its martyrs to the extent that it is a worthy custodian of their legacy. The heroism of its martyrs stems from the public perception that they are acting freely and that their sacrifice is authentic and necessary. Hizballah’s use of tactical martyrs in the form of suicide attackers is therefore made possible by—but also severely constrained by—the centrality of authentic martyrdom within the Shiite tradition the group represents. In other instances of suicide bombing, when the organization intervened too directly—or pushed the use of self-sacrifice beyond its followers’ willingness to tolerate it—the illusion of freedom became difficult to sustain. Hizballah’s leaders seem to have no desire to test the patience of their followers in this respect, opting for the ongoing celebration of a relatively few suicide attackers rather than diluting their value by throwing more suicide attackers at Israel (or by admitting to their use in Lebanese political feuds).

For Hizballah, the public ritual surrounding its suicide attackers continues to provide symbolic and strategic value while the organization’s much greater political and military capabilities have reduced the need for the tactical advantages provided by suicide attackers. The global jihadi movement, on the other hand, has no connection to local populations and is therefore not subject to the limitations that maintaining local legitimacy places on the use of suicide attackers. The reliance of its leaders on suicide attackers should therefore be interpreted as an indication of their political weakness. Indeed, Mohammed Hafez observed regarding jihadi suicide attackers in Iraq, “Their marginality is at the root of their lethality.”12

Suicide bombing therefore seems to be a technology with a very limited window of opportunity within which it can provide both tactical and strategic benefits. Groups lacking in (or competing for) power and legitimacy can use suicide bombing as an effective way toward both ends temporarily, provided a sense of community need exists and a willingness to die among certain members creates the possibility of systematic self-sacrifice. With the passage of time, however, the symbolic and demonstrative aspects of suicide bombing diminish as it becomes commonplace rather than rare. At this point, groups must decide whether to halt such operations. Like the jihadis (or the Tamil Tigers), they could continue to deploy suicide attackers as long as they have members willing to kill themselves. In this case, the group will continue benefiting from the tactical capabilities of human control systems. Such use of suicide bombing, however, will almost certainly come to be perceived by the broader community for what it really is—the human use of human self-sacrifice devoid of freedom and authenticity—and accordingly will fail to yield strategic benefits.

[We] would be nowhere without Radio Shack.

Readily available, over-the-counter technology lies at the heart of the most lethal and effective weapons deployed by militant groups. U.S. forces in Iraq learned the extent to which commercially available electronics had benefited their adversaries in 2006 when they confiscated several specially modified suicide vests. In addition to the necessary explosives, the vests also included web cams for transmitting video footage of the operation to the bombers’ handlers in real time. The vests were also equipped with a remote detonation capability, giving the support team the ability to detonate the bomber when and where they saw fit, or perhaps in case the bomber were to have second thoughts.14 Collectively, this hybrid of innovations—explosives, consumer electronics, and the culture of martyrdom—offered militants, at minimal expense, similar capabilities to those provided by unmanned drones for their American adversaries. Both weapon systems provide controllers with the ability to survey potential targets from a distance, to determine in real time the best place and time to attack, and then to destroy the selected target, all at no risk to themselves.

Suicide bombing provides a weapon that is uniquely suited to the needs and capabilities of terrorist groups, providing them with the best of both worlds: the precision and sophistication of the most complex technologies as well as relative simplicity and reliability. Adding to the effectiveness of suicide bombing is that the organizations employing it do not need to build manufacturing infrastructures from the ground up, but instead can utilize cultural and social factors to realign existing technological systems to their own ends. Their effectiveness in doing so suggests that the high-technology endeavors of the developed world have actually eroded, rather than enhanced, the capabilities of states relative to nonstate actors.15

The tactical effectiveness of suicide bombing is further explained by the fact that militant groups utilizing this weapon have emphasized their strengths by creating an alternative to the weapons of their adversaries instead of trying to appropriate their enemies’ weapon technologies directly. In 1982 the quick destruction by Israel of the PLO’s conventional forces and of the Syrian air force convinced Hizballah’s founders of the need to pursue alternatives that would not be as easily targeted and overwhelmed by Israel’s weapon systems. They chose therefore to emphasize portable, reliable, easily concealable weapons to complement their guerrilla tactics, and as a result were far more effective militarily in dealing with Israel than the PLO and Syrians had been. U.S. forces in Iraq and Afghanistan ran into similar difficulties. The sophisticated weapon platforms used in these theaters were originally designed to engage other high-tech weapons, such as aircraft and tanks, while the actual weapons deployed by insurgents were more difficult for electronic firepower systems to recognize and engage effectively. Historian Martin van Crevald observed this trend many years ago, writing “[M]any modern weapons tend to act as parasols. Whereas their own electronically supported firepower is wasted in antiguerilla operations, they allow guerilla warfare and terrorism to take place below the sophistication threshold that they themselves represent.”16

This high “sophistication threshold” comes at a monetary cost that limits the number of weapons that can be deployed and reliably maintained. After an exhaustive statistical analysis of U.S. military programs in the 1970s, Franklin C. Spinney found that ever-increasing defense budgets were not leading to higher levels of military readiness but instead were contributing to a self-perpetuating cycle of ever-increasing complexity in weapon systems that outpaced improvements in operational effectiveness. The data, he found, suggested “a general relationship between increasing complexity and decreasing material readiness.”17 These lessons challenge the assumption that when it comes to international security, newer, more technologically advanced, and (inevitably) more expensive weapon systems are inherently better.

Such a narrow understanding of technology has been a major factor encouraging the U.S. military to underestimate the capabilities of nonstate adversaries. For example, the most effective weapons deployed against coalition forces in Iraq and Afghanistan have been relatively simple emplaced bombs, now generally called improvised explosive devices (IEDs). Such weapons were originally developed by the People’s Will in the 1880s and have been a staple of guerrilla forces ever since. Nevertheless, coalition forces were unprepared to deal with these low-tech weapons, and some leaders seem to have been taken by surprise when technologically “inferior” forces were able to inflict significant harm on their better-armed and better-equipped adversaries.18 A U.S. Air Force general interviewed by Peter Singer expressed frustration at this state of affairs, saying, “We have made huge leaps in technology, but we’re still getting guys killed by idiotic technology—a 155mm shell with a wire strung out.”

Of course there is nothing at all idiotic about IEDs or suicide bombers, and the effectiveness of these weapons suggests that any technological system—high-tech, low-tech, and anything in between—must be thoroughly integrated into the various layers of the human context with which it must interact in order to be effective. What has traditionally been regarded as low-tech can sometimes be more effective because it interfaces more seamlessly with the human elements of the system and allows for creativity in use. More complex technologies, on the other hand, can be expensive, be narrow in application, require higher levels of training and education, and be much more demanding in terms of maintenance, making them brittle and prone to failure.

In addition to revealing the potential limitations of “high” technology, another lesson one can draw from suicide bombing is a consequence of the complexity of technology practice and the corresponding difficulties that accompany the transfer or use of technologies across cultural boundaries. All three vertices of the technology practice triangle are necessary for technology to function as a sustainable social phenomenon; the ease with which a technological system can diffuse, however, varies significantly from vertex to vertex. The technical element does flow across cultural boundaries rather easily. After all, physical devices, be they precision-guided munitions, suicide bombers, or cell phones, function in exactly the same manner around the world. It is therefore extremely tempting to think that the other levels of technology practice will move just as easily, but the diffusion of technology, as shown here, is rarely straightforward. The organizational processes by which devices are produced, manufactured, and managed are much “stickier”; that is, they tend to adhere to the culture or society that originally developed them, making them context dependent.19 The cultural values that determine whether or not a given technology will be perceived as necessary or even desirable are even stickier, often necessitating a reconfiguration of the first two elements of a particular system and resulting in a different iteration of the technology as it is accommodated in a new environment.

When the technical element of a given technological system is introduced into a new context, it is inevitably interpreted and understood according to the values and norms of the receiving culture. This can lead to incompatibility and dissonance between devices and cultures and, in turn, sometimes explains why the diffusion of technologies can be so problematic and why seemingly effective military technologies often fail to produce political victories. Such interpretations also explain why cultures on the receiving end of airpower, however judiciously used, might see it as inhumane and also why few outside of the jihadi subculture see the use of suicide bombers as noble or admirable.

Because such physical devices as weapons function across borders, they can be attractive as a first means of settling disputes. Each successful use at the tactical level might appear to validate the system that produced the weapon, so it is easy to perceive each tactical use as a step toward strategic or political victory. Because two cultures are involved, however, evaluating the technology according to its users’ set of values will always be insufficient. If the targeted culture cannot come to accept the values that produced a particular weapon system, that culture will not acquiesce to the society that produced the weapon. In such a case, no number of small tactical steps will ever lead to victory, and short of escalating the conflict to the point of extermination, such use of technology will never provide political and social stability.20

In recent years, the governments of Israel and Sri Lanka have put an end to the use of suicide bombing by their respective foes by intensifying their occupations of contested land and reasserting control over territories where their foes previously had greater freedom of action. The Israeli government dealt with Palestinian suicide bombers by reestablishing authority over parts of the West Bank, building a barrier between Israeli and Palestinian populations, and using trained personnel to spot and intercept prospective bombers. These measures allowed the Israeli government to raise the cost of suicide missions by ensuring that most of them would fail and reinforcing Palestinians’ growing skepticism toward suicide attacks. The Sri Lankan military conquered Tamil territory, defeated the LTTE, and killed Prabhakaran, destroying the organizational element of Tamil suicide bombing.

These successes, even if only temporary, are consistent with the model of suicide bombing as a technological system presented in this work and suggest that there are many avenues by which suicide bombing can be counteracted, corresponding to the vertices and relationships of the technology practice triangle. Disrupting one or more vertices disrupts the intensifying relationships between them and de-escalates the entire process. The Israeli government dealt with Palestinian suicide bombing at the technical vertex by making the weapon less effective and therefore less attractive as a means of combating its occupation. The Sri Lankan state dealt with the LTTE at the organizational vertex of its suicide-bombing complex. The steps taken by U.S. forces in Iraq during 2006–2007 suggest a way of approaching suicide bombing at the cultural-social vertex. By engaging rather than confronting local Iraqi groups, U.S. troops were able to exploit fundamental ideological differences between these organizations and the jihadis. Working with local groups reduced the perceived need for an extreme form of resistance, such as suicide bombing, that also contributed to discrediting the jihadi narrative and the cultural allure of the suicide bomber.

Despite the success of this change in the U.S. approach toward the militants, very real problems in Iraqi security ensured that suicide bombers would continue to be effective at the technical level in terms of inflicting harm. The jihadi groups most responsible for suicide bombing were not eliminated, so the organizational factor persisted. Thus two of the three vertices of the Iraqi suicide-bombing complex remained after the U.S. surge. Although suicide bombing declined appreciably, it remained a significant problem. Similarly, in the Palestinian territories the culture of martyrdom, while perhaps diminished, has not been completely eliminated nor have the militant organizations that previously deployed suicide attackers. Since these elements remain, there is still a possibility that Palestinian groups might resort to the regular use of suicide bombing should they perceive a need.

The case of the Tamil Tigers is unique because of Prabhakaran’s role in LTTE suicide bombing. Not only did his death bring about the end of the LTTE, the organizational vertex of this particular suicide-bombing complex, it also ended the elaborate culture of martyrdom that transformed individuals into suicide bombers because the LTTE’s Black Tigers pledged their allegiance to Prabhakaran personally. In short, two elements of the suicide-bombing complex were completely eliminated in Sri Lanka, explaining the lack of suicide attacks since Prabhakaran’s death. While the causes of Tamil militancy have by no means been addressed, and the possibility remains that a violent secessionist campaign on the part of the Tamil people may resume at some point, there is no reason to believe that suicide bombing will play the integral role in such a campaign as it did in the LTTE’s failed crusade.

That suicide bombing is susceptible to intervention in many different areas is a logical consequence of the nature of technological systems. Such systems diffuse with difficulty, or sometimes not at all, because numerous factors must fall into place simultaneously for them to function effectively in a new context. In other words, for suicide bombing, as for all other forms of technology, there are more ways to fail than there are to succeed. Countering suicide bombing therefore requires recognition of the multiple ways in which the failure of suicide bombing can be encouraged as well as prudence in action so as not to inadvertently facilitate its acceptance by creating a perceived need for suicide bombers or legitimizing their users.

Early on the morning of May 2, 2011, a U.S. Navy Special Forces team killed Osama bin Laden during a raid on his compound in the city of Abottabad, Pakistan. Information gathered from his computers suggests that bin Laden played a more significant role in directing al Qaeda’s operations than had been thought. Nevertheless, his death had little immediate operational impact on the jihadi movement. It certainly did not bring an end to jihadi suicide attacks as Prabhakaran’s death had ended LTTE suicide bombings. Instead, the weekend after bin Laden’s death there were several suicide attacks against coalition forces in Afghanistan, and the following week a brutal pair of blasts in Pakistan killed eighty people. The blasts were claimed by the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan, whose leaders declared that the bombings were revenge for bin Laden’s death.21

The use of suicide attackers in these revenge operations suggests strongly that in the short term bin Laden’s death put enormous pressure to act on the movement’s remaining leaders. Given the declining fortunes of global jihadism more generally, and specific challenges facing its individual franchises, remaining jihadis could ill afford to let such an event go unchallenged. As Bruce Hoffman noted, “For al-Qa‘ida, now is the time to ‘put up or shut up’ as the remaining leadership will surely attempt to prove that the movement retains its vitality despite the death of its founder and leader.”22 Overall, however, the movement did far more shutting up than putting up. Its leaders remained out of the spotlight, undoubtedly fearful that information obtained from bin Laden’s computer files could put them at greater risk of being targeted. More than a month after bin Laden’s death, al Qaeda still had not named a formal successor. Five weeks after bin Laden’s death, Ayman al-Zawahiri finally released a video eulogizing the late leader and vowing another catastrophic attack against the United States, but many questioned the ability of the movement to make good on such a promise.23 Shortly afterward, Zawahiri emerged as the recognized leader of al Qaeda.

Over the short term, bin Laden’s death focused a movement that had become increasingly fragmented, but it also raised questions regarding the ability of even a re-focused jihadi movement to carry out high-profile operations. Over the long term, bin Laden’s death may well deprive the movement of legitimacy and coherence, particularly if it proves unable to match Zawahiri’s words with deeds.

The way in which bin Laden was killed—by a team of highly skilled people—is particularly significant. Throughout the 1990s, bin Laden self-consciously built up an image of himself and his movement as morally superior Davids battling the technological Goliath that is the United States. Suicide bombers were essential to this narrative, as they were supposed to embody the movement’s reliance on people and of faith over machines. Had bin Laden been killed by a drone strike, the event would have played perfectly into the story he had been constructing. Instead, people played a central role in the raid that killed him, and it was the training and quality of the people—supplemented but not replaced by technology—that allowed the mission to succeed. The fact that the number of unintended casualties was kept to a minimum also mattered, as it demonstrated a respect for the lives of the United States’ adversaries that had often been lacking in military missions.

That bin Laden died in a struggle with his enemies will undoubtedly contribute to his status as a martyr within the movement.24 Martyrdom, however, is such a flexible construction that no matter how he passed away, there would have been a crew of martyrologists ready to frame his death in a manner appropriate for their own agendas. What is more significant is that his death was understood by much of the world, and the Islamic world in particular, as appropriate and just. The martyrologists of al Qaeda will construct a heroic posthumous version of bin Laden’s death, but the true test will be whether this image will be accepted by anyone outside the jihadi movement.

Bin Laden’s symbolic power stemmed not only from his involvement in the 9/11 attacks but also from the aura of invincibility that seemed to surround him as he eluded U.S. forces for nearly a decade. The shattering of this aura diminishes the al Qaeda brand. Political developments in the Middle East in early 2011, particularly the toppling of Hosni Mubarak’s government in Egypt by peaceful protestors, compounds al Qaeda’s situation. The unfolding of events in Egypt and Tunisia challenges the validity of the al Qaeda narrative, as Zawahiri, in particular, has justified his group’s use of violence by claiming that dictators like Mubarak could only be toppled through force. With a diminished brand name and nonviolent alternatives competing with the jihadis’ methods in the market of disaffected Muslims, it appears that whatever boost the movement received from the death of bin Laden could be short lived. This situation is of course fluid and could easily be reversed. Should the jihadis find it within their capabilities to respond dramatically to bin Laden’s death, and should political gains in Egypt and elsewhere prove to be temporary, then the suicide manufacturers in the jihadi movement might yet have enough material to keep themselves in business for years to come.