Palestinian Suicide Bombing in

the Second Intifada and After, 2000–2010

On the evening of March 27, 2002, nearly 250 Israelis gathered to celebrate the Feast of Passover in the dining room of the Park Hotel in Netanya, north of Tel Aviv. A young Palestinian man named Abdel Azziz Basset Odeh entered the hotel lobby and loitered for a while. When one of the hotel guests noticed his suspicious behavior and shouted a warning, Odeh quickly entered the dining room and detonated the explosives strapped to his body. Nineteen people were killed immediately; within days the death toll would climb to 29 dead and 154 injured. The devastation to the hotel was so extensive that authorities initially worried that the building might collapse.1

The attack had been designed to inflict maximum loss of life. Odeh’s bomb consisted of approximately forty pounds of explosives and shrapnel and was so large and difficult to conceal that one account reports that he was disguised as a pregnant woman. Killing so many Israeli civilians, many of them elderly, on a holy day was meant to be a provocation toward the Israeli government, but the message the attackers hoped to send was even broader. At the time of the attack, Arab leaders were meeting in Beirut to discuss a peace plan drafted by Saudi Arabia. Gen. Anthony C. Zinni, the U.S. mediator sent to negotiate a cease-fire between the Israelis and Palestinians, was in the area as well. Hamas representatives made it clear that the brutality of the attack had been strategic, intended to enrage the Israelis to such an extent that neither a cease-fire nor a lasting peace would be possible. Hamas spokesman Mahmoud al-Zahar declared, “The Palestinian people do not want to see Zinni succeed in his assignment to the region. The bombing tonight came as a reaction to what is happening in Beirut. We want to remind the Arabs and the Muslims what resisting the occupation means.”2

The Park Hotel bombing had much in common with previous use of suicide attackers by Hamas and Islamic Jihad. It was planned well in advance and designed to achieve several objectives simultaneously. Suicide bombing by Palestinians was in a state of flux, however, and by the end of the year, three significant differences emerged that would distinguish the suicide bombing of the second intifada from the suicide attacks of the 1990s. First, the most obvious difference was the exponential increase in the number of attempted and successful attacks. Second, the technology had spread to groups, including Fatah and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, that had not previously utilized it, and became a means by which the various factions competed with one another for the allegiance of the Palestinian people. There was thus more of a bottom-up dynamic, with local leaders using their bombers opportunistically rather than directing them with the level of forethought that characterized the attacks of the 1990s. Third, women were used as suicide attackers, first on an improvisational basis and later with more regularity.

Although there had been optimism among many Palestinians regarding the peace process in 1999 and the Islamist parties were apparently in retreat, underneath the surface there was less reason for hope. It was clear from both the Israeli and Palestinian perspectives that the Cairo-Oslo process, which had postponed resolution of the toughest issues dividing the two parties, had been taken as far as it could go. Therefore, upon assuming office in mid-1999 as Israeli prime minister, Ehud Barak indicated that he wished to pursue a final, comprehensive peace agreement and was generally regarded as being willing to take the necessary steps in order to reach one.3 Two major factors (among others) stood to undermine the process. The most important, by far, was the ongoing construction of Israeli settlements in the West Bank. The number of settlers in the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and Gaza had nearly tripled between 1990 and 2000. The building of settlements had not been explicitly forbidden in the Cairo-Oslo process agreements, so many Palestinians came to believe that the entire peace process was actually meant to distract and forestall Palestinian political initiatives while Israelis continued to colonize the occupied territories at will.4

The other factor was PA president Yasser Arafat, who governed the Palestinian territories like a private fiefdom and presided over the Palestinian Authority like an autocrat, dispensing offices to his subjects based on personal loyalty rather than professional competence. Although Arafat was hard working and ascetic, his cronies did not share these traits, so the Palestinian Authority became mired in corruption.5 The PA also became an extension and tool of Fatah, as Arafat used the PA’s law enforcement capabilities to weaken his opponents and to strengthen his own faction.6 Lacking the ability to deal with the important, big-picture issues—settlements, refugees, and borders—and no interest in governing effectively at the local level, the Palestinian Authority became representative, in the eyes of many Palestinians, of the shortcomings of the peace process as a whole.

With these factors looming in the background, the administration of Bill Clinton brokered meetings between Barak and Arafat in the United States over the summer of 2000. At the time, however, neither Barak nor Arafat had the political capital to make the compromises necessary for a final peace. Barak had just narrowly survived a vote of no confidence in the Knesset before departing for talks at Camp David, demonstrating that despite whatever popular support for the peace process might have existed, the political reality was that Barak was increasingly isolated. Arafat, for his part, believed that he was being pushed too far on the issues of Jerusalem and especially refugees.7 After the summit collapsed, over the next several months U.S. mediators attempted to broker a loose framework for peace, the terms of which Arafat felt he could not accept and thus ultimately rejected in January 2001. By that point, violence had completely replaced the peace process as the defining characteristic of the Israeli-Palestinian relationship.

When campaigning for election as prime minister, Ehud Barak had promised that within a year he would withdraw Israeli forces from the occupation zone in southern Lebanon because being there no longer served a strategic purpose. Hizballah’s media-savvy leaders took credit for the eventual withdrawal, in May 2000, claiming that its guerrilla campaign had driven out the Israeli occupier. Palestinian militants agreed with this assessment and by summer 2000 had begun to consider whether a Hizballah-style guerrilla campaign might be an effective way to attack Israel.8

With the peace process effectively stalled in mid-2000, all that was necessary to reignite hostilities was a spark, which occurred in September in the form of a visit to the Haram al-Sharif, the Islamic holy site in Jerusalem’s Old City, by Ariel Sharon, one of Israel’s most polarizing politicians. The Palestinian Authority had approved the visit of a Likud Party delegation headed by Sharon, but the excursion was unusual in that it violated modern Jewish custom, which prohibits worshippers from ascending and praying on the Temple Mount.9 Furthermore, Sharon, a conservative hard-liner and supporter of the settler movement, had purchased an apartment in East Jerusalem and was preparing to challenge Ehud Barak in elections to be held in early 2001. Thus his decision to visit the Haram al-Sharif was interpreted by many to be a provocative political move, intended symbolically to lay Israeli claim to the heart of East Jerusalem.10

Some Palestinian leaders proclaimed on television that Sharon’s visit would desecrate the Haram al-Sharif and called on Palestinians to defend the area. On Thursday, September 28, when Sharon climbed up to the Temple Mount, surrounded by hundreds of police, a skirmish broke out between the security forces and Palestinians.11 The following day, after Friday prayers, hundreds of Palestinians exited the al-Aqsa mosque and threw stones down onto the plaza adjoining the Western Wall and pelted police with rocks. Israeli soldiers responded with live ammunition, killing eight Palestinians. The next day, footage was broadcast around the world reportedly showing Muhammad al-Dura, a boy huddling with his father against a wall for protection, being shot and killed in an exchange of fire between Israeli and Palestinian forces. He was immediately portrayed as the first martyr of the second, or al-Aqsa, intifada.12

While the uprising of late 2000 was cast in the same terminology as the intifada that erupted in 1987, it rapidly became far more lethal, as Palestinian leaders, including Arafat, encouraged their followers to use deadly violence. As events unfolded, it became clear that the inspiration and model for this uprising was Hizballah’s guerrilla war against Israel, not the civil disobedience of the first intifada. Thus stone throwing and civil disobedience were accompanied by small-arms and mortar fire and the use of Molotov cocktails. Israel responded, in turn, much more lethally than it had in 1987. After six days of confrontations, sixty Palestinians were dead. By October 10, ninety Palestinians had been killed and more than two thousand injured, as opposed to a handful of Israeli fatalities, mainly among the Israel Defense Forces (IDF).13

Arafat’s role in the second intifada was particularly controversial. Some believe that he deliberately instigated the violence to pressure Israel.14 This interpretation, however, appears to credit Arafat with having more control over the various factions than he actually possessed. Nonetheless, Palestinian Authority leaders, Arafat first among them, could have done more to restrain the violence and consequently must share blame for its escalation.15 It is likely that Arafat believed that more violence might help his position. If this was, indeed, the case, he was terribly mistaken. He was unable to control the fighting, which became decentralized, with local commanders and fighters taking the initiative, driving and escalating the violence from the grass roots. Furthermore, when Israel responded by retaking territory in the West Bank—in the process destroying infrastructure, raiding PA offices, and carving up the area with new barriers, Israeli-only roads, and checkpoints—the PA’s ability to deliver services collapsed. At this point, Hamas stepped up its role of tending to the needs of the Palestinian people.16 It used this situation to its advantage to make steady political gains at the expense of Fatah.

Suicide attackers were not used in the early weeks of the second intifada, suggesting that Palestinian fighters initially had in mind a guerrilla war against the Israeli military more so than terrorist attacks against Israeli civilians. Hizballah, after all, had used suicide attackers only sparingly in its guerrilla war against Israel. The first suicide bombing of the second intifada was carried out by Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) on October 26, when twenty-four-year-old Nabil Arair attacked an IDF post in Gaza, killing himself and injuring one Israeli soldier. It was the first suicide attack in nearly two years. Over the next several months, PIJ and Hamas attempted several more attacks, some of which inflicted numerous injuries, but which failed to cause any Israeli fatalities. Eventually, on March 4, 2001, a Hamas bomber killed three people, and from that point on suicide attacks became the most reliable means available to Palestinian militants for killing Israeli soldiers and civilians alike. Suicide bombings—which had dropped to zero in 1999 and only three to five attempted attacks in 2000—climbed steadily throughout 2001. By year’s end, Hamas and PIJ had conducted approximately thirty attacks.17

The turn toward suicide bombings made operational sense from a Palestinian viewpoint because other forms of armed resistance were not having much of an effect on Israeli armed forces or society. That is to say, after six months, the Palestinians found themselves fighting a very unsuccessful guerrilla war. Gal Luft, a former lieutenant colonel in the Israel Defense Forces, observed the following:

From the Palestinian perspective . . . the results of the guerilla campaign in the first year were poor, especially considering the duration of the fighting and the volume of fire. Palestinian forces launched more than 1,500 shooting attacks on Israeli vehicles in the territories but killed 75 people. They attacked IDF outposts more than 6,000 times but killed only 20 soldiers. They fired more than 300 antitank grenades at Israeli targets but failed to kill anyone. To demoralize the settlers, the Palestinians launched more than 500 mortar and rocket attacks at Jewish communities in the territories and, at times, inside Israel, but the artillery proved to be primitive and inaccurate, and only one Israeli was killed.18

Given this situation, Luft understood the switch toward suicide attackers to be a switch to a much deadlier and more effective strategy. During 2001 this strategy evolved in such a way that more conventional resistance groups, including Fatah and its armed branch, the Tanzim, would continue the guerrilla campaign while the Islamist groups steadily supplemented the guerrilla war with a wave of terror attacks targeting Israel’s civilian population.

In 2002, as groups that had never previously attempted suicide attacks began using them, the total exceeded fifty, which represented more than all the successful and attempted suicide attacks from 1993 to 2000. These attacks, many carried out without warning in densely populated civilian areas, resulted in hundreds of Israeli dead and wounded of all ages and walks of life. In one of the most devastating cases, an attacker wearing an explosive vest detonated himself outside a Tel Aviv discotheque on a Friday evening, June 1, 2001. He killed twenty-one people, primarily teenagers and young adults, many of them recent émigrés to Israel from Russia and other post-Soviet states.19 More than one hundred people were injured.

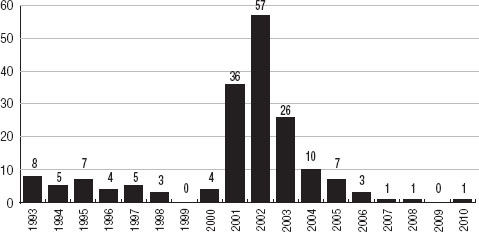

The number of successful suicide attacks in the second intifada peaked in 2002 and then declined rapidly as the uprising wound to an end in 2005 with a cease-fire between Israeli and Palestinian forces in the aftermath of Arafat’s death, in late 2004. After the intifada, three attacks succeeded in early 2006, only one in 2007, one in 2008, none in 2009, and one in 2010. Overall, suicide attacks comprised less than one-half of 1 percent of all Palestinian attacks from 2000 through 2006, but they caused 50 percent of civilian fatalities.20 The escalation of suicide bombing in the second intifada and its subsequent cessation occurred as illustrated in Figure 6.1, which also includes numbers from the first wave of suicide bombing in the 1990s to provide perspective.

Between March 1999 and December 2000 Palestinians’ approval of suicide bombings soared from 26 percent to 66 percent while the number opposed declined from 66 percent to 22 percent.21 Furthermore, the bombers, immortalized in videos broadcast by Hizballah’s al-Manar television, became celebrities, seemingly the only heroes young Palestinians could claim as their own. Lacking confidence in the political process and politicians, and mired in economic misery, violence and displays of determination became important sources of honor for many Palestinians, which served to elevate the social status of the suicide bomber.22 In this environment, groups that were not utilizing suicide attackers, such as Fatah, risked losing political credibility. Thus in early 2002 the al-Aqsa Martyr’s Brigades, a new organization within Fatah, took credit for their first suicide attack.

FIGURE 6.1Suicide Bombings by Palestinian Groups, 1993–2010

Sources: data for 1993 through 2004 are from Ami Pedahzur, Suicide Terrorism (Cambridge, U.K., and Malden, Mass.: Polity Press, 2005), app., 242–53, and Mohammed M. Hafez, Manufacturing Human Bombs: The Making of Palestinian Suicide Bombers (Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace Press, 2006), app. I, 79. For 2005 through 2010 sources and details, see Table 6.1.

Formed in late 2000, the al-Aqsa Martyr’s Brigades were a loosely structured outfit, having been organized by lower-ranking local cadres who retained operational autonomy to such an extent that they have been described as “a cluster of loosely connected gangs.”23 The brigades could respond directly to popular pressure to strike at Israel, and did so in the name of Fatah, while their autonomy allowed Arafat a degree of deniability. Arafat even occasionally made half-hearted attempts to shut down the groups. The Marxist-oriented Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine conducted three suicide attacks during 2003–2004 that were likely motivated by a desire to avenge the group’s leader, Abu Ali Mustafa, who had been killed by Israeli forces in 2001.24

The killings and assassinations of senior Palestinian leaders by Israeli forces caused authority and initiative to be handed down to younger, less-established leaders, who often chose targets based on their availability and the possibility of striking them effectively, not on whether the attacks would result in political gains that could be consolidated. This created a bottom-up dynamic in which centralized control was ceded to local commanders. The result, as some militant leaders later admitted, was that from 2002 onward a coherent strategy for suicide bombing no longer existed. Instead it resembled “organized anarchy.”25

On the morning of January 27, 2002, Wafa Idris, a twenty-six-year-old Palestinian woman and member of Fatah, traveled from her home in Ramallah to Jerusalem, passing without incident through an Israeli checkpoint. She loitered for a brief time in a shoe store, appearing to a sales clerk to be nervous and preoccupied. In her knapsack she was carrying a bomb to give to her brother Khalil, also a Fatah member who was then to carry out a suicide mission on behalf of the al-Aqsa Martyr’s Brigades. Idris had been chosen to carry the explosive under the assumption that as a woman, she would arouse less suspicion traveling into Jerusalem. Having spent time in the store, Idris hurried toward the exit while attempting to remove some cosmetics from her knapsack. Her bag became stuck in the door, and as she struggled to free it, the bomb detonated prematurely, killing Idris and an eighty-one-year-old Israeli man. Dozens of people were hurt.26

That same day Arafat had addressed a huge crowd of Palestinian women from his compound in Ramallah, declaring them to be his “Army of Roses” that would crush Israeli tanks and lead the way to Jerusalem.27 When Wafa Idris became the first such shahida (female martyr), her act had an electrifying effect on the Palestinian people. Soon, dozens of other women were asking for a chance to emulate her by martyring themselves.28 The leaders of Fatah initially did not know how to respond to the incident because they believed that women should have a supporting rather than a leading role in military operations. It soon became clear to them, however, that shahidas could potentially be very effective weapons since social customs and dress codes made Muslim women more difficult for Israeli guards to search. Furthermore, the Israeli press took an almost lurid interest in female suicide bombers, giving the attacks even greater propaganda value.29

Fatah leaders decided to declare Wafa Idris the first martyr from the al-Aqsa Martyr’s Brigades, making political capital out of what was likely an accident. Not to be outdone, the Islamists responded in kind, deploying their first female suicide bomber in early 2003. Religious officials formulated Islamic justifications for female suicide attacks where none had previously existed, just as they had developed justifications for male suicide attackers after the fact.30 For example, Hamas leader Sheikh Yassin was initially critical of the phenomenon but changed his position when Hamas began to utilize female suicide bombers in early 2003, arguing that jihad was an imperative for all Muslims, men and women, and that all would be rewarded in the afterlife.31 According to the journalist Barbara Victor, Yassin was unwilling to show her the Quranic passages detailing the rewards that female suicide attackers would receive in paradise. Instead he replied, “It is my job and the job of other sheikhs and Imams to interpret the Koran. . . . The people have our trust. Women along with all Muslims have the right and the duty to participate in suicide bombings to destroy the enemy and bring an Islamic state to all of Palestine.”32 By 2006 sixty-seven Palestinian women had either carried out suicide attacks or had attempted to do so.33

Leaders of Fatah and Hamas and other organizations created a dignified image of female suicide bombers, holding them up as women anxious to take part in the armed struggle with the full support of Palestinian society. The media were sometimes complicit in this process by portraying female suicide bombers as representing a move toward equality in a patriarchal society.34 Empirical research, however, reveals a different picture. Often the motivations for female suicide attackers were different from those of male bombers, with personal crises typically serving as the catalyst driving young women to volunteer to carry out attacks.35 Once having volunteered, peer pressure and other forms of coercion were used to force women to carry out their missions, regardless of whether it was ultimately what they truly wished. Furthermore, the psychological process in which bombers were recruited and deployed was especially cynical and hypocritical in the case of female bombers. Women continued to play no role at all in the upper ranks of the groups that used them and were not treated with a sense of camaraderie on the part of their handlers. While they were celebrated publicly, they remained unequal to male bombers throughout the process.36

Because of preexisting trends and the first wave of suicide attacks in the 1990s, a culture of martyrdom already existed in Palestinian society at the start of the second intifada. This devaluing of life relative to death made intentional death in the course of militant attacks socially and culturally acceptable. Also, during the second intifada, there was a strong perceived need on the part of Palestinian organizations for a weapon providing some type of relative advantage for striking at Israel. The use of violence by Israel contributed significantly to this process.

There were thousands of automatic rifles at the disposal of the Palestinians in late 2000—in part because of the creation of the PA security forces—but Israeli forces were difficult to reach. Fortified borders and outposts separating them from the Palestinian population had been created during the 1990s as the Palestinian Authority took administrative control over territory from which Israeli forces had withdrawn or redeployed. IDF soldiers were therefore in a much better defensive position when violence erupted in September 2000 than they had been in the 1990s, which accounts for the poor performance of Palestinian conventional attacks and helps explain the decision to escalate the struggle by using suicide bombers.37

For the most part, Israeli forces responded in kind, with small-arms fire the norm during 2000 and 2001. Nevertheless, two weeks after fighting began in late September 2000, ninety Palestinians had been killed and two thousand injured, while the IDF had suffered only a few casualties. By November 319 Palestinians had been killed by Israeli forces, more than half of them while participating in civilian demonstrations. Autopsies showed that most had been shot in the head or neck, indicating that Israeli troops, even when attempting to quell protests, were not shooting just to intimidate or disperse crowds, but to kill. Shlomo Ben-Ami, a member of Ehud Barak’s cabinet at the time, found the IDF response to be completely disproportionate to the provocation.38 Thus, while the Israeli military did indeed demonstrate a level of restraint relative to its overwhelming capabilities, from a Palestinian perspective Israel was killing and injuring large numbers of Palestinians and suffering few casualties in return. Such an external factor goes a long way toward explaining why suicide bombing came to be used in the second intifada, but this external factor alone is insufficient for explaining the growth and diffusion of suicide bombing during the course of the fighting. For that, internal factors must be considered as well.

When the peace process ground to a halt and Palestinian militants perceived a need for suicide attackers, glorification of the bomber served to stoke the internal dynamics of escalation. Sari Nusseibeh witnessed this process, writing, “For me, the clearest signal that the Palestinians were at their wits’ end was the way the [Israeli] invasion intensified the cult of the suicide bomber.”39 This internal process was exactly the opposite of that in the late 1990s, when the Islamists toned down their rhetoric and temporarily abandoned suicide attacks in imitation of more socially acceptable parties, such as Fatah. In the second intifada the process was reversed, with Fatah emulating the Islamists, who in turn felt compelled to be more violent to set themselves apart. Thus a positive feedback loop contributed to the dramatic escalation in attacks.40 In short, the spread and intensification of Palestinian suicide bombing resulted from the external factor of Israeli brutality interacting with the internal factor of a deliberately created culture of violence that fueled Palestinian suicide attacks.

The exponential increase in suicide bombing from 2000 through 2002 was matched by an equally dramatic decline after 2003. As with the increase, the decline was the result of at least two factors, which collectively lowered the effectiveness and therefore the advantage offered by suicide bombing and opened up alternatives to it as a means of political mobilization.

The response of the Israeli government was largely responsible for reducing the effectiveness of suicide attacks. In the aftermath of the Passover bombing, the government launched Operation Defensive Shield, reoccupying territory in the West Bank and Gaza Strip that had been placed under the administrative (and sometimes security) control of the Palestinian Authority. At the same time, the government began construction on a massive barrier separating Israel and Israeli settlement blocs in the West Bank from Palestinian areas.41 Palestinians entering Israel and East Jerusalem were subjected to lengthy waits and searches, and Israeli security personnel became adept at behavioral recognition techniques that allowed them to better spot incoming attackers. By June 2002 the Israelis were detecting more than 50 percent of would-be attackers, and according to Ariel Merari’s data, the following year they stopped 184 out of a total of 210 attempted suicide attacks.42

The effectiveness of these security measures may well have had a deterrent effect among potential bombers as it became far more likely that they would face an indeterminate period in an Israeli jail instead of achieving the coveted status of martyr. At the very least, it became more difficult for Palestinian organizations to dispatch their bombers to targets in Israel. After peaking in 2003, the total number of attempted (as opposed to successful attacks) declined steadily, with the exception of a spike in attempted attacks in 2006 (see Table 6.1). The greater costs in preparation and planning and the higher probability of failure served to erode the relative advantage that suicide bombers had provided in the first years of the second intifada.43

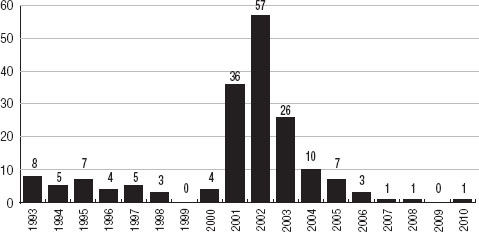

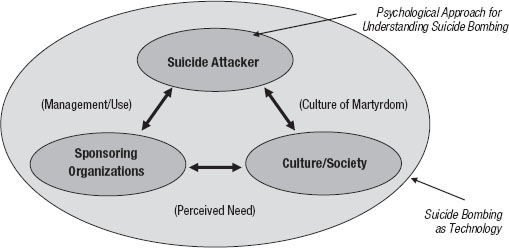

While the Israelis’ measures reduced the advantages suicide bombing offered the Islamists, changes in the political arena played a role as well, by opening up the possibility of political participation for Hamas and transforming the character of the organization’s rivalry with Fatah. After Arafat’s death in late 2004, Fatah’s new leader, Mahmoud Abbas, agreed to a cease-fire in early February 2005.44 For the most part Fatah adhered to this truce when it came to the use of suicide bombers and regularly condemned Islamist suicide attacks in 2005 and 2006. When members of the al-Aqsa Martyr’s Brigades carried out a suicide attack in March 2006, it was in response to Hamas’ victory in legislative elections held in January and should be understood as an effort by Fatah to regain militant credibility after it had lost its leadership role in the Palestinian Authority.45 Leaders of Palestinian Islamic Jihad chose not to participate in the elections, and their organization continued to play the role of spoiler, claiming most of the relatively few successful suicide attacks after 2004. In 2010 there was one successful suicide attack, which was credited to Jalil al-Ahrar (Galilee Freedom Battalions), a new fringe group composed of Israeli Arabs and sometimes referred to as the “Imad Mugniyah group,” after the Lebanese-born militant responsible for planning the Islamic Jihad Organization bombings in Lebanon in 1983.

TABLE 6.1 Suicide Bombings by Palestinian Groups, 2005–2010

Sources: Worldwide Incidents Tracking System, National Counterterrorism Center, wits.nctc.gov (accessed on April 7, 2010); Greg Myre, “Suicide Bomber Kills an Israeli Security Officer in Gaza,” New York Times, January 19, 2005; Greg Myre, “Islamic Jihad Says It was Behind Tel Aviv Bombing,” New York Times, February 27, 2005; Steven Erlanger and Greg Myre, “Suicide Bomber and Two Women Die in Attack in Israeli Town,” New York Times, July 13, 2005; Steven Erlanger, “Israel Suffers First Suicide Attack since Gaza Pullout,” New York Times, August 28, 2005; Greg Myre and Dina Kraft, “Suicide Bombing Kills at Least 5, Israeli Police Say,” New York Times, October 26, 2005; Greg Myre, “Palestinian Bomber Kills Himself and 5 Others Near Israel Mall,” New York Times, December 6, 2005; Steven Erlanger, “3 Killed by Suicide Bomber at Checkpoint in West Bank,” New York Times, December 30, 2005; Dina Kraft and Greg Myre, “Palestinian Suicide Bomber Wounds 20 in Tel Aviv,” New York Times, January 20, 2006; Myre, “Bomber Kills 3 Israelis as Hamas Takes Power”; Greg Myre and Dina Kraft, “Suicide Bombing in Israel Kills 9; Hamas Approves,” New York Times, April 18, 2006; Greg Myre, “Suicide Attack Is First in Israel in 9 Months,” New York Times, January 30, 2007; Isabel Kershner, “Hamas Claims Responsibility for Blast,” New York Times, February 6, 2008.

Hamas responded in two ways to the changing environment during 2004–2006. First, it kept up pressure on Israel, but increasingly resorted to unguided rocket attacks from Gaza into Israel rather than suicide bombings. Rockets were less accurate and far less deadly, rarely resulting in a fatality. However, they could be fired on a regular basis and in large numbers, thus causing fear and anxiety among Israelis within striking distance. More important, since rockets are an indirect-fire weapon that goes over defenses rather than through them, the rocket campaign could not be stopped by the same measures that were making suicide bombing less effective. This is another instance where a new perceived need led to the use of a different technology.46

Second, in the PA elections in 2006 Hamas’ candidates challenged Fatah’s on the grounds of corruption and the provision of social services. Hamas’ victory was a surprise to most. The elections were deemed free and fair by international observers and earned Hamas the right to form the PA government. The U.S. and Israeli governments, however, refused to work with a Palestinian government that included Hamas, which in their eyes was only a terrorist organization. Hamas continued to launch rocket attacks on Israeli towns; meanwhile, efforts between Hamas and Fatah to form a Palestinian national unity government proved to be short-lived. The underlying tensions between Hamas and Fatah erupted into civil war in June 2007. Hamas routed Fatah and PA forces in Gaza and took control of the territory, resulting in a de facto division of the Palestinian territories, with Fatah governing the West Bank and Hamas ruling in Gaza, its traditional base.47

The character of the intra-Palestinian violence in 2007 was different from that in the 1990s. Hamas had previously avoided open conflict with the Palestinian Authority and instead differentiated itself from Fatah by taking a more extreme position on Israel. In 2007 the rivalry between the two was much more direct, expressed through political competition for the allegiance of the Palestinian people and military competition for resources and territory. The competitive dynamic that had earlier fueled extreme violence against Israel in the form of suicide attackers came instead to be directed toward the Palestinian community itself, in the form of intense fighting between the two factions. The necessity of having community support for the use of suicide attackers almost certainly precluded their use in this fratricidal struggle.

The Israeli government instituted an economic blockade against the Gaza Strip in the aftermath of the Hamas takeover, justifying it as a response to the ongoing rocket attacks that Hamas continued to carry out in 2007 and 2008. The blockade soon came to have a crippling effect on Palestinian daily life. In mid-2008 Hamas and Israel reached a six-month cease-fire agreement that allowed for a partial restoration of deliveries of food and other necessary supplies. When the cease-fire expired in December, Hamas militants again escalated their rocket attacks. At the end of the month, Israel responded with Operation Cast Lead, an invasion of Gaza that lasted through much of the following January. Despite Israeli efforts to limit the damage, the civilian population suffered more than one thousand deaths and four thousand injuries.48

In October 2008, during the cease-fire that predated Operation Cast Lead, members of Palestinian Islamic Jihad granted an interview to a BBC reporter and revealed to him that they were training female suicide bombers while waiting for the end of the cease-fire to use them against Israel.49 Shortly thereafter, during the fighting in early 2009, members of Hamas claimed via the Internet that they were in the process of training a cadre of suicide bombers, referred to as “Ghosts,” and alleged that “tens” of these bombers had already infiltrated Israel and were awaiting orders to retaliate for IDF operations in Gaza. Despite these claims, there were no Palestinian suicide attacks against Israel in 2009.50 Hamas even refrained from rocket attacks throughout 2009, leading Israeli defense minister Ehud Barak to assert that Operation Cast Lead had succeeded in deterring Hamas from attacks on Israel.51 Others have suggested, however, that Hamas was not deterred, but instead simply showed signs of responsibility by restraining its militancy in accordance with the wishes of its constituency, which had largely lost hope in violent solutions.52 It would be premature to say that suicide bombing has ended in the Israeli-Palestinian struggle. Rather, the current situation is one in which suicide bombing offers few political or military advantages.

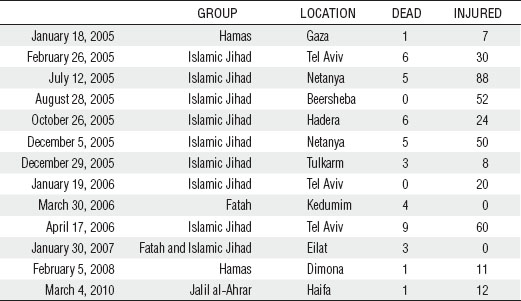

Ariel Merari’s empirical research on suicide bombing, spanning more than two decades, reveals the phenomenon to be an extremely complex process that cannot easily be reduced to a single-variable explanation. Instead, he argues that a full explanation of suicide bombing must address three interactive components: the community, the organization, and the psychology of the individual.53 In 2006 Max Taylor and John Horgan proposed a similar model for understanding terrorism more generally that was based on the understanding that terrorism is an ongoing process, rather than a fixed state, that emerges from interactions between at least three groups of variables—what they call “setting events,” personal psychological factors, and the social/organizational context.54 In both models seemingly fixed qualities matter less than do interactions, because interactions are what change behavior and ultimately decide whether terrorism (or suicide bombing) becomes established as a response to a perceived grievance. Both of these models bear a striking resemblance to the model of technology practice originally presented in the introduction and then modified to incorporate suicide bombing (see Figure I.4, on page 17). This model is reprinted here as Figure 6.2.

As noted in the introduction, it is typical in technologically advanced societies for people to understand technology in a restricted sense, focusing purely on the technical element—the knowledge, tools, skills, and so on that affect the world and solve problems found in their societies. In a similar vein, many analyses of suicide bombing have focused on a restricted understanding of the phenomenon—the psychology of the individual bomber—as opposed to the organizational and cultural phenomenon of suicide bombing. Now that a great deal of empirical detail is available on suicide bombing by Palestinians, theirs makes an ideal case for illustrating suicide bombing as a form of technology. Such an understanding must begin at the organizational level.

FIGURE 6.2Suicide Bombing as Technology Practice

Source: Adapted from Arnold Pacey, The Culture of Technology (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1983), 6.

Mohammed Hafez asserts that organizations “are the essential nexus between societal conflicts and individual suicide bombers. Without organizations, aggrieved individuals cannot act out their violence in a sustained manner.”55 His insight into suicide bombing by Palestinians represents a truism of technology—the centrality of organizations and management for determining issues of production, consumption, and use.

In the case of suicide bombing, organizations have sought to make self-sacrifice a regular occurrence by controlling and narrowing the range of actions available to certain individuals. They have then marketed these tactical martyrs to their community as an advantageous form of weaponry. In short, they have sought to control directly management and perceived need, two of the three relationships that characterize the overall process of suicide bombing. At the same time, they have demonstrated that they can have an influential, albeit indirect role in the third relationship, the creation and maintenance of the culture of martyrdom that facilitates community acceptance of the death of the suicide bomber.

The production of suicide attackers and subsequent execution of suicide attacks involve several specialized skill sets, such as intelligence gathering, weapon production, and recruitment and training, necessitating the involvement of several specialized groups to carry out a mission. Intelligence gathering and manufacturing of bombs are skills that are more generally used within militant groups, leaving recruitment and training as the area of “specialization” for the production of human bombers.

The organizational element of Palestinian suicide bombing proved to be surprisingly consistent across the ideological spectrum in the early 2000s. Merari found no “Hamas style” or “Fatah style,” but instead identified minor differences that varied at least as much within the organizations as between them. There was a clear division of labor between leadership and the pool of candidates from which prospective bombers were selected. Leaders did not participate in suicide attacks, and some admitted that they would not allow members of their families to become suicide attackers. Some even had difficulty understanding why the people they recruited and trained were willing to blow themselves up. This arrangement was logical in that leaders of militant groups often have valuable experience and specialized skills that are difficult to replace, whereas the loss of the relatively inexperienced individuals often used as bombers is much easier for a given organization to endure. Merari also found that the significant organizational gap between managers and bombers correlated with strong differences in personality types between the two, as managers and other leadership figures were much more confident and sure of themselves than were the would-be bombers he was able to interview.56

Recruitment was facilitated by the many different personal motivations that compelled individuals to first explore the prospect of becoming a suicide bomber. General research on the motivations of Palestinian suicide attackers, coupled with more specialized research revealing differing motivations between male and female suicide bombers, demonstrates that there was a broad spectrum of individual motivations for suicide bombing, ranging from the selfless or altruistic to the more personal, private, and selfish.57 Some individuals were driven by a sense of powerlessness, frustration, humiliation, or despair. Others seem to have been driven by a desire to demonstrate their commitment to their faith and to the organization to which they belonged. Others had more personal motives, such as avenging the death, injury, or humiliation of a loved one. Some were driven by economic concerns, knowing that their deaths as suicide attackers would bring financial benefits to their surviving family members.58

Underlying this broad range of motivations was a relatively consistent set of personality characteristics among suicide attackers and would-be suicide attackers. Merari found many suicide bombers to be socially marginal with a keen sense of social failure, which in turn likely made them susceptible to the lure of becoming a suicide attacker.59 For such people, suicide bombing offered a socially respectable means to resolve their particular personal crises and alleviate feelings of marginality and failure.60 These benefits, like the benefits for the Black Tigers, were not posthumous, although posthumous rewards were undoubtedly an important factor for religiously motivated recruits. The decision to become a bomber also brought with it a sense of control and empowerment and was therefore a form of transformation, not only from the perspective of the organization but also from the perspective of the recruit. Many young people in particular could not resist the possibility of being transformed from a weak individual into the most powerful weapon Palestinian groups had to offer. Indeed, many young people in their testimonies spoke of their decision in terms of transformation or “becoming.”61 The benefits that collectively accrued to the bombers and to their loved ones in this life and the hereafter made deciding to become a suicide attacker a potentially attractive option, even for those who otherwise might not have considered taking their own lives.

Training and indoctrination followed recruitment. The length of the training process varied significantly, depending on the particular time and group, but regardless of duration focused less on practical military training and more on the use of ceremonies and rituals to establish control over the behavior of the individual, thus binding him or her to the organization and mission. In some cases, the preparation consisted of trials to test the commitment of the recruit, for example, mock burials or dress rehearsals of the pending attack.62 In other cases, care was taken to deflect the attention of the bomber from the finality of the act. In these instances, the commitment was ritualized as a form of marriage, a rite of passage that signified a beginning rather than an end.63 From an organizational perspective, the specific preparation was less important than the overall objective, which was to bind the recruit to the organization, community, and therefore to his or her own commitment through a dramatic public ritual.

An important element of the ritual process was production of a last testament from the bomber, sometimes written but often in the form of a videotaped testimony. These recorded commitments served a number of purposes. They were powerful propaganda tools directed at the organization’s adversaries for purposes of intimidation and at their own communities for purposes of inspiration and recruitment.64 From an organizational perspective, the tapes proved that their bombers went to their deaths willingly and had not been coerced or deceived.65 This is important for establishing the legitimacy of the group. If young people are willing to kill themselves for it, goes the logic, the group and its cause must obviously be worth the sacrifice. On the other hand, if the group has to manipulate or trick people to get them to carry out attacks, as the Provisional IRA did with its coerced human bombs, the group’s leaders must be hypocrites and cowards.

The tapes also served the organizations’ needs in another, very practical respect—as a control mechanism over the potential bomber.66 Making the tape public established the candidate’s commitment to the cause and to the group. It, in theory, intensified the prospective bombers’ sense of belonging and camaraderie, which in turn were powerful motivating factors.67 After that point, any effort by the bomber to back out of the mission would be seen not only as an act of individual cowardice but also as a shameful betrayal of his or her comrades. The commitment represented on the videotape was understood to be so binding that from that point onward, potential bombers were referred to as living martyrs.68 The tapes were therefore one of the most important steps in compressing the behavior of potential bombers, closing off potential alternatives or “escape routes” until death or humiliation remained the only choices.69 It is clear from the testimonies of some bombers who were intercepted before completing their missions that the use of such videotaped testimonials had indeed been intended to coerce and intimidate those who otherwise would not choose to kill themselves.70

The celebration of martyrdom that the making and viewing of these tapes promotes may exploit general psychological trends that predispose individuals for suicide by making them more familiar and comfortable with the prospect of ending their own lives.71 Psychologist Thomas Joiner has explored individual suicide at length, beginning with the premise that violent self-injury is extremely difficult for nearly all people. His clinical work on suicides and attempted suicides suggests that this resistance to self-injury is difficult to overcome, leading him to conclude that those who are most likely to succeed in suicide are those who have diminished their own fear through repeated self-injury. What Joiner calls mental practice—rehearsing acts of self-violence in the mind as a means of overcoming the natural inhibitions toward self-injury and death—is a variation on repeated physical self-injury. Analyzing more than three thousand patients deemed to be at risk for suicide, Joiner asserts, “Through mental rehearsal of violent death by suicide, these patients have acquired more of the ability to enact lethal self-injury.”72

Joiner’s work complements earlier research on individual suicide that indicates that suicide is largely a learned phenomenon. Understanding suicide in such a manner sheds light on it as a social phenomenon, particularly suicide “contagions,” which are episodes in which highly publicized or extensively reported suicides seem to encourage additional individuals to take their own lives. David P. Phillips, who in the early 1970s was among the first to study this phenomenon systematically, dubs this the “Werther Effect,” in reference to Goethe’s Sorrows of Young Werther. After the book’s publication, Goethe apparently became concerned that he had inadvertently inspired young German men who had read the book to take their own lives in imitation of the story’s hero.73 Although the Werther Effect was not reliably documented in Goethe’s time, Phillips believes there were several cases of the phenomenon in twentieth-century America.

Some recent research examines the factors that influence the social impact of individual suicides. In one well-known case, sensational media reporting on individuals who had killed themselves by throwing their bodies in front of trains in Vienna’s subway network led to enough copycat deaths that the researchers established guidelines for media reporting to tone down the events and make them seem less attractive to potential imitators. After the new guidelines went into effect, subway suicides in the city declined appreciably, though they did not disappear.74 Based on cases such as these, the researcher Graham Martin wrote that as of the late 1990s, “We must now accept that reports that are ‘front page’, repeated and/or multi-channel, have suicide prominent in the report or in the title, glorify suicide in some way, are accompanied by photographs, discuss in detail the method of suicide and, in particular, concern celebrities, will influence others to suicide.”75 All of the elements of this description—particularly glorification and celebrity—apply to the use of suicide bombers’ video testaments, footage of attacks, and commemoration in music videos to promote suicide bombing in Palestinian circles.

In his pioneering study, Phillips endeavored to reconcile his finding that suicide has a social aspect to it with Durkheim’s pioneering work that argued that individual suicides were the result of social alienation (or what he called anomie, in contrast to his conception of altruistic suicide, as discussed in Chapter 1). Phillips suggested that alienation was indeed at the heart of individual suicide, but that alienated individuals had two mechanisms by which to deal with their issues. The first, of course, was suicide. The second was to overcome isolation by affiliation with a social group or movement. The two were simply different answers to the same problem, and in the rare cases of suicide contagion, both were simultaneously present. Suicide was still a way out, but by imitating others, suicidal individuals were in fact seeking belonging and affiliation.76 For Palestinian suicide attackers (as well as others), the potential of becoming a suicide bomber offered them a two-pronged solution to their alienation—through affiliation with a respected social movement and suicide.

The findings on suicide indicate that training methods emphasizing mental rehearsal of the act of suicide and the public glorification of suicidal violence, regardless of its regional and cultural manifestations, confer significant power on militant organizations that use such attacks. These organizations not only recruit individuals and encourage them to commit suicide, but also make them more capable of taking their own lives than they might otherwise be. The organizations endeavor essentially to create suicide contagions similar to the spontaneous suicide contagions documented by researchers.

For suicide bombing to be effective as a coercive strategy directed against an adversary, the bombers must be understood by that adversary as being representative of the mindset of their community. If the entire group is thought to be willing to fight to the death, the phenomenon becomes intimidating; alternatively, if the bombers are seen as being aberrant or pathological, the effect is greatly diminished. From an organizational perspective, this situation encourages the mobilization of strong public support for the use of suicide bombers. Furthermore, effective control and management of prospective recruits require the complicity of families and communities, which in turn requires organizations to make efforts to market suicide attacks as a necessary and admirable means of resistance in order to make the suicide of young people socially acceptable. For this part of the suicide-bombing process, the acceptance of families is paramount, for if a family accepts (and better yet welcomes) the decision of a son or daughter to become a suicide attacker, then the biggest hurdle standing in the way of overall community acceptance is cleared.

For Palestinians, external factors, in the form of Israeli violence, went a long way toward convincing the community that the use of suicide attackers was justified. As seen in other instances of suicide bombing, a sense of existential crisis can be used to justify the most extreme forms of resistance, and certainly the Palestinians’ case is not an exception. Palestinian militant groups justified the use of suicide attackers in terms of necessity. For example, one member of Hamas’ external leadership declared, “This weapon [the suicide bomber] is our winning card, which turned weakness and feebleness into strength, and created parity never before witnessed in the history of struggle with the Zionist enemy. It also gave our people the ability to respond, deter, and inflict harm on the enemy; it no longer bears the brunt of punishment alone.”77

Of course, it was one thing to establish the general need for suicide attackers, but quite another to convince a family that taking its child’s life is necessary. To justify individual acts of suicide bombing, organizations make use of the videotaped testimonials to convince a family that the decision was made by the individual and that the group was simply facilitating the desire of the individual to strike back on behalf of the community. Militant groups also exploit the complex and sometimes contradictory emotional state of parents grieving for a lost child. Most parents are emotionally shattered by their child’s death, especially death by suicide. The depth of the loss in turn leads to a search for meaning, which often leads to rationalization of the child’s death, to give it purpose, and thus to temper the sense of loss. In the case of suicide bombers, parents often demonstrate two very different emotional states: pride in the deed but at the same time grief at the death of their child.78 Militant groups work to publicize the former and minimize the latter.

Members of Hamas sometimes visited the family members of their suicide attackers to ensure that they did not soil the heroic image of the shahid by expressing their grief inappropriately. This is another aspect of managing suicide attacks that they may well have learned from Hizballah, whose leaders carefully controlled media access to families of suicide attackers.79 Palestinian journalist Zaki Chehab relates an instance of this type of image management. In the immediate aftermath of the death of a Hamas suicide bomber named Ismail, Chehab visited the young man’s family. Both father and mother were weeping. Two muscular young men from Hamas arrived and went to work on the father, using a number of strategies to assuage his grief. They encouraged him to be proud and assured him that the first people to follow a martyr to heaven were his parents. They asked him, “Would you rather your son had died in a car accident or from drowning or as a drunk than dying as a hero for killing Israeli soldiers?” After fifteen minutes, the father’s grief had been converted into pride and gratitude. Chehab notes,

This poignant scene provided an insight into the personal and organizational side of Hamas. The two men were Ismail’s comrades in Al Qassam. They knew in advance that he was embarking on his mission, and kept complete secrecy until the news broke of what they considered was his success. They had come not only to comfort the family, but also to perform a typical Hamas public relations mission. It is imperative for the family of a Hamas fighter to be seen in front of the world as proud of their beloved son rather than bitter or tragic and they should extol Hamas’ belief in the battle and the glorious afterlife their son is destined to experience.80

The claims made by militant groups to reassure their communities—including that their suicide attackers were acting in accordance with their families’ wishes—should therefore be treated skeptically.81

In Palestinian circles, istishhadia, or martyrdom, is differentiated from individual suicide, which is forbidden by Islamic law. Suicide, which is premised on self-interest—what Durkheim called egoistic suicide—is a sin. Martyrdom, done on behalf of others—what Durkheim called altruistic suicide—is a noble deed because it is oriented toward others. According to one Hamas thinker, “[O]nly a fine line separates suicide from sacrifice. Which is determined by the intention of the actor.”82 Because this line is so fine, from the perspective of the individual, acts of suicidal violence are most likely to be perceived as authentic martyrdom when they receive organizational confirmation; the bomber must state his or her intentions and work through a group in order to prove that the act is public and social rather than individual and selfish. This situation confers an extraordinary power on sponsors of suicide attacks.

Such organizational power is challenging to maintain, however, because the public recognition of authentic martyrdom ordinarily requires that the individual be acting freely and without organizational influence or coercion. Organizations are thus faced with the challenge of trying to perform two very different tasks at the same time—providing direction and control through the group to the individual attacker and guaranteeing the certainty of the individual’s freedom to the community. In the case of the Tamil Tigers, this challenge was not so pronounced given Prabhakaran’s power over his recruits and contempt for dissent at any level. For groups without such power, the task is more difficult; recall the challenges that the Provisional IRA had in maintaining the legitimacy of the hunger strike over the summer of 1981.

Palestinian groups, particularly the Islamists, solved this paradox by minimizing detection of the coercive elements of bomber management and promoting a full-fledged culture of martyrdom that made suicide bombing redemptive at the individual and community levels and therefore acceptable to both. This culture of martyrdom is the third relationship of the suicide bombing complex and the most challenging for groups to manipulate because they can influence it only indirectly.

Videotaped testimonials of suicide attackers served this purpose by making it appear as though martyrdom was being chosen freely by young Palestinian men and women. Leaders of their sponsoring organizations understood that it was imperative for their role in writing and producing the testimonials to remain hidden. Even when evidence existed that the leadership had written particular testimonials, they nonetheless attributed them to the bombers to make the act seem more authentic. It was essential for the leadership to appear as mediators or brokers, rather than drivers, in the process, lest they be seen as cynically manipulating the lives of their followers.83

Mohammed Hafez has shown that Palestinian Islamist organizations went to great lengths to recast cultural symbols and traditions to make suicidal violence meaningful rather than nihilistic. This was a deliberate process of construction, using culture to constrain the possibilities of individuals and shape the relationship between these individuals and their communities. Hafez wrote, “Religion, culture, and identity serve as ‘tool kits’ from which organizers of collective action strategically select narratives, traditions, symbols, rituals, or repertoires of action to imbue risky action with morality.” He documented five strategies through which this was achieved.84 In this manner, the act of suicide was reinterpreted as an opportunity and a challenge that had the potential to redeem both the individual and the community. Securing community support via this relationship was vital for making suicide bombing a reliable rather than a sporadic form of attack; many failed attackers have indicated that they would not have considered carrying out a suicide mission if they had believed it was against the wishes of the Palestinian community. Merari goes so far as to say that it was community support that normalized the very idea of suicide missions and that without such backing suicide attacks “would probably have seemed bizarre to the suicides themselves.”85

Suicide bombing by Palestinians is the best documented example of such attacks as a constructed process directed toward the production of a particular weapon system. Like most manufacturing processes, it was characterized by organizational differentiation, the acquisition and maintenance of task-specific skill sets, and a clear division of labor. The managers within the system sought to extend their control over the production process, the psychological training of individual recruits, and the prospective market. They exercised this control directly when possible, and indirectly when necessary, by influencing the culture of martyrdom that linked bombers and community. All the various facets of Palestinian suicide bombing—the psychology of the bombers, the videotapes, the seemingly proud families, and the cultural reverence for martyrdom—were therefore related, and more important, deliberate.

Because the makers and marketers of Palestinian suicide bombers were so concerned about maintaining a positive public image of their role in the process, their attacks also reflected a more general trend in suicide bombing—the challenge of reconciling the tactical utility of suicide bombers at the group level with the need to maintain the authenticity of martyrdom at the individual and community levels. Instances of intense external pressure, such as existed in 2001 and 2002, tended to compress the two levels of tactical martyrdom by making it acceptable in lieu of other means of resistance. When external pressures eased, as they did in late 2004 and afterward, however, issues of legitimacy trumped those of practicality. This made suicide bombing difficult to sustain, and it was discontinued (at least for the time being). The lesson for militants was that for groups whose control over their members and communities is limited or contested, reconciling the tactical and strategic utilities of martyrdom is the most challenging managerial task in the overall process of suicide bombing.