The simplest method of obtaining target discrimination is through its recognition by intelligence.1

But in truth there is no difference between their [American and Israeli] attacks and ours. Both of us have one thing in common—to annihilate the enemy. The rest is mere logistics and differences in techniques. Whether one attacks by planes or by car bombs the objective is the same. Who is to say that they are better or more civilized just because they use twentieth-century equipment? Who decides that it is more right or correct or even more acceptable to kill one’s enemy by warplanes rather than car bombs?2

The impact of the September 11, 2001, al Qaeda attacks on the United States extended beyond their physical and financial effects. They shredded Americans’ confidence about their security and left behind a sense of vulnerability not seen in the United States since the tensest moments of the Cold War. In the months and years after the attacks, another factor added to the psychological toll—frustration at the failure of U.S. intelligence services to have anticipated the attack or to intercept the attackers beforehand. The frustration was well-founded in some respects. The FBI and CIA had the information they needed to disrupt the plot, yet because of a lack of vision, interagency mistrust, and poor leadership they were unable to make effective use of it.

In other respects, the failure to anticipate 9/11 is understandable because the operation was designed to exploit blind spots in the collective thinking of the U.S. security community. The attacks completely rewrote the rules of airliner hijacking. Previously, hijackings had been theatrical affairs in which the hijackers traded power over their hostages’ lives for concessions in a ruthless kind of negotiation.3 The September 11 hijackings, however, were about aircraft, not people; in fact, the passengers were potential liabilities, rather than assets, as demonstrated by the resistance of the passengers on United Flight 93 and their success in stopping the hijackers from reaching their destination. The goal of the hijackings was to reprogram the guidance systems of the airliners so that they could be used as massive cruise missiles. To direct these missiles at their targets, the hijackers installed their own control systems—pilots who had been trained in the specific task of crashing the airliners into buildings. Since the security measures extant at the time had been established on the assumption that the lives of passengers were more valuable to hijackers than the aircraft, they proved to be ineffective for this fundamentally different kind of attack.

The September 11 attacks therefore had more in common with the United States’ arsenal of precision-guided munitions than with the history of aviation terrorism, a fact noted by two experts on the “precision revolution” in air-delivered weapons. Soon after 9/11, Michael Russell Rip and James M. Hasik wrote, “The two attacks in New York displayed pinpoint accuracy against targets only half a city block wide. This sort of precision is otherwise attainable only with laser, electro-optical, or satellite guidance.”4 Prior to the al Qaeda operation, this sentence probably would have read “such precision is only attainable” with the systems they reference.

After 9/11, it is essential to think more broadly about technology and to recognize the attacks on that day as having employed a fundamentally different form of guidance technology in which computation and decision making were performed by individuals instead of computers. From such a perspective, the pilots of the four diverted aircraft were not “normal” hijackers carrying out an agreed upon tactic; nor did they “use” the aircraft to attack the United States. Rather, they were the control elements of a weapon system whose destruction was a necessary and anticipated consequence of a successful mission, as is the fate of a precision-guided munition (PGM) produced by a technologically advanced state. Also like a PGM, the entire system—consisting of aircraft, hijackers, and pilots—was used by actors who were not physically present, in the case of 9/11 the al Qaeda leadership that had planned and directed the mission.

This basic relationship—the use of human beings by other human beings—is the defining characteristic of suicide bombing. Horror at the brutal results of suicide attacks and an almost lurid fascination with the mental state of the individuals who commit such violence have tended to deflect attention away from this relationship, but it is the constant presence of “use,” more than any other factor, that has made suicide bombing problematic to analyze in terms of previously accepted understandings of self-sacrificial violence. For example, suicide bombers have typically been understood within their communities and their sponsoring organizations to be martyrs in the traditional sense of the word—that is, individuals who willingly sacrifice their lives on behalf of a cause. The willingness of such individuals to give their lives, in turn, has the strategic effect of validating the cause and the organizations that fight for it.

At the same time, however, suicide bombing differs appreciably from martyrdom as conventionally understood because historically martyrs have for the most part accepted suffering for themselves without inflicting harm upon others. The power of martyrdom lies in the willingness of the individual to suffer, even unto death, which stems from the martyr’s certainty in his or her beliefs and a sense that to compromise those beliefs would be a worse alternative than death. Since suicide bombing by its nature inflicts harm, often grievous, indiscriminate harm, many analysts strongly believe that suicide bombing cannot be understood in terms of martyrdom. To reconcile these two understandings of suicide bombing, one must shift attention away from individual bombers and toward the organizational element that uses them.

The presence of users in suicide bombing confirms that it is indeed different from most historical instances of martyrdom, but the fact that the bombers are often willing to die on behalf of others suggests some overlap with the classical martyr’s willingness to die for a cause. It is therefore proffered here that suicide bombing be understood as a new type of martyrdom—that is, “tactical martyrdom.” Suicide bombing can still generate the strategic, legitimizing power of classical martyrdom, but with an added dimension. By allowing organizations to control what would otherwise be an individual act, suicide bombing makes “martyrdom” predictable and usable, thereby contributing significantly to the power of militant groups by providing them with intelligent guidance systems for their weapons.

Tactical martyrdom is therefore different from most traditional understandings of martyrdom. This does not necessarily imply the opposite, however, which would be that suicide attacks are the same as individual suicides. Certainly, many suicide attackers appear to have been motivated by despair, fatalism, or even self-aggrandizement, making their choice selfish and therefore similar to that of typical suicides. At the same time, the social dimension of the violence is consistent with the history of martyrdom in different cultural traditions. Suicide bombers therefore do not fit readily into the categories of martyrdom or individual suicide. Instead, to understand suicide bombing, it is more appropriate to think of lethal self-violence in terms of a spectrum stretching from individual, selfish suicide to classical martyrdom on behalf of others, with today’s tactical martyrs falling somewhere in between. Depending on individual motivations, some may fall closer to the ideal of classical martyrdom, some may fall closer to individual suicide, but few can be easily pigeon-holed into either extreme. In this sense tactical martyrdom is not exactly martyrdom and is not exactly suicide, but something different—the human use of human self-sacrifice.

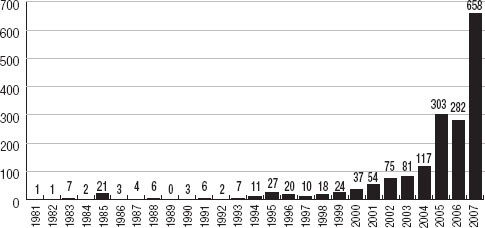

For more than three decades, suicide bombers have been used by a host of extremist groups in increasingly diverse and innovative ways. In 2004 such bombers carried out at least 102 attacks, successfully striking targets in Afghanistan, Iraq, Israel, Turkey, Uzbekistan, and elsewhere. The final toll for 2005 was more than 300 suicide bombings, resulting in 3,171 fatalities. According to the Washington Post, the total number of suicide attacks globally declined in 2006, to 282, but then more than doubled in 2007, to 658 operations (see Figure I.1).5

FIGURE I.1Global Suicide Attacks, 1982–2007

Source: Robin Wright, “Since 2001, a Dramatic Increase in Suicide Bombings,” Washington Post, April 18, 2008.

Even as suicide bombing became a significant global security problem it remained difficult to analyze. Since few people understand why an individual would choose to kill him- or herself while indiscriminately killing others, the psychology of the individual suicide bomber attracted a disproportionate share of public fascination and scholarly attention after the phenomenon became a regular occurrence in the 1980s. This focus on the mindset of individual bombers precluded understanding the organizational character of suicide bombing for many years. In particular, the issues of agency and use were often mistakenly attributed to the bombers or their cultures rather than their sponsoring organizations.

As suicide bombing became more common in the first decade of the current millennium, the frequency and ingenuity with which organizations trained and utilized their followers prompted rethinking, and in the early 2000s a scholarly consensus on the centrality of organizational control of suicide bombing took shape. In 2004 Bruce Hoffman and Gordon McCormick articulated this consensus in terms that evoke technological processes of manufacturing. They wrote, “Although suicide attacks often appear to be the actions of deranged individuals, with rare exceptions they are seldom the product of an individualized choice. They are almost always the product of an organizational process designed to transform otherwise normal individuals into agents of self-destruction.”6

The addition of analysis of the organizational component reveals suicide bombing to be a process that operates simultaneously on three levels: that of the individual bomber, the culture that supports the bomber and bombing, and the organizations that make and use the bombers. Of significance, the psychology and therefore rationality of suicide bombing varies depending upon the level of analysis. Although scholars have demonstrated that there can be a rational motivation for the use of suicide bombing at the group level, this same logic is often completely missing when one examines the desires and motivations of the individual bombers. What is needed at this point is an integrated approach that encompasses all three levels as well as the simultaneous presence of rational and irrational motivations that exist within suicide bombing.7

Although numerous books and articles have been published on suicide bombing, scholars remain tentative when addressing the subject. The most common metaphor used to describe the suicide attacker is that of a smart bomb. For example, Bruce Hoffman writes that suicide bombers are “the ultimate smart bomb,” and Mohammed Hafez suggests that suicide bombers “are perhaps the smartest [bombs] ever invented.”8 Still, in spite of the smart bomb metaphor, most observers continue to regard suicide bombing as a tactic—a pattern of behavior that is particularly lethal and tends to be used when all others have failed, perhaps, but still a tactic.9

This designation remains incomplete at best because it only takes into account the act of lethal self-violence carried out by the bomber (or bombers) against his or her targets. This designation does not address the numerous factors at the individual, organizational, and cultural levels that make suicide bombing possible. In short, calling suicide bombing a tactic describes how suicide bombers are used but does nothing to explain how and why they are made, or why some groups use them well, some poorly, and others not at all. It may have been appropriate when overall understanding of the phenomenon was poorer, but given the current state of knowledge, a more complex explanatory framework is necessary.10 The Business of Martyrdom: A History of Suicide Bombing provides such a framework by integrating recent empirical research on the organizational character of suicide bombing to push the insight of the smart bomb metaphor to its logical conclusion by arguing that tactical martyrdom is a form of technology that is consistent with—and understandable in terms of—other technological systems.

The Business of Martyrdom is a historical analysis of the technology of suicide bombing that traces its invention and reinvention, diffusion, and transformation at the hands of its users. A historical approach is necessary because suicide bombing has changed significantly over the past three decades. The more recent studies of it are structured thematically, rather than historically, and thus fail to present a consistent, chronologically organized narrative. The thematic approach reveals an underlying but unwarranted assumption—that one explanation for suicide bombing can be applied to a broad range of cultures and societies with minimal modification. Suicide bombing, however, is a dynamic process that takes on some of the characteristics of the cultures employing it yet also has some common elements observable across societies. The suicide bombing of the 1980s was similar to but not the same as the suicide bombing of the 2000s, so to try to approach the subject as if they were indeed identical poses significant problems for any analysis.11

This book provides a fluid explanatory mechanism, that of the technological system, to account for suicide bombing’s dynamic character without sacrificing analytical rigor or the possibility of comparative analysis. Technologies, properly understood, are processes that integrate behavior, thinking, and physical materials and transform them into goods or services of greater utility. Understanding suicide bombing historically as a technological system takes into consideration the haphazard, contingent process by which such bombing began and also offers a plausible explanation for its diversity and diffusion. The spread of technologies is never uniform or homogeneous; instead, societies embrace or reject specific technologies depending on how a technology allows them to solve problems consistent with their values and norms. In all cases, the same basic technology will vary from region to region as the different cultures adapt it to their own standards and expectations. Each cultural manifestation of a particular technology is thus a hybrid of general and specific characteristics.

In July 2001 FBI agent Ken Williams filed an electronic memo with his superiors in which he suggested that Osama bin Laden was making a sustained effort to send his followers to the United States to learn to fly commercial airliners at civil aviation colleges. The memo was based on fieldwork through which Williams had determined that an unusual number of individuals who were of “investigative interest” to the bureau had registered for flight schools in Arizona.12 In the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, this report appeared to be prophetic, prompting inquiries into exactly why the FBI had not acted on the so-called Phoenix memo. The bureau’s defense was that the memo had been little more than a hunch; Williams himself had not thought about hijacking, but that al Qaeda was planning a long-term infiltration of the civil aviation industry. Thus, even when presented with this information, the U.S. intelligence community was unable to anticipate the nature of the threat posed by passenger aircraft being used as weapons, despite the fact that al Qaeda had already made repeated use of suicide bombers for its most spectacular attacks. In its evaluation of the situation, the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States (the 9/11 Commission) attributed this lack of foresight to an overall lack of imagination on the part of intelligence agencies when dealing with the threat of terrorism.13 This explanation is only partially true.

Analysts did indeed have difficulty imagining something along the lines of the 9/11 attacks, but this does not imply that they were not applying their imaginations to the world of terrorism and mass-casualty attacks. Indeed, their imaginations were running wild, but down all the wrong paths. Since the second Bill Clinton administration, analysts had been certain that terrorists were on the verge of carrying out mass-casualty attacks using so-called weapons of mass destruction—nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons. This obsession became so deeply ingrained in the thinking of the security community that analysts could no longer imagine the use of any other type of weapon for such a scenario. Timothy Naftali writes that as of 2001, “No one assumed that al Qaeda would press forward with a mass casualty event that required only conventional weapons.”14

Analysts in the U.S. security community tended to be locked into a mode of thinking that equated military power, and therefore security, with technology. They defined technology in terms of material devices independent of human context and understood “high” technology to be more expensive, more complex, and inherently more effective than older systems.15 Analysts therefore projected their own thinking and biases regarding technology onto their adversaries, imagining that terrorist groups, like states, would need complex technologies to carry out high-consequence operations. Less-complex technologies, in contrast, were assumed to be less effective. The 9/11 attacks proved these assumptions wrong.

Because security officials tended to think of technology in terms of devices rather than people, they could not recognize suicide attackers as a form of guidance technology since physically there is little resemblance between a human suicide attacker and precision-guided munitions. Nevertheless, both systems perform an identical task: they both allow human intelligence to affect delivery and detonation of an explosive interactively in real time. In technology, how well a particular system does a given job is the yardstick that matters, not whether different approaches to the same job resemble one another.16

In recent decades, the U.S. government has invested billions of dollars in a host of artificial intelligence systems to replicate human powers of cognition. None of these systems will ever be mistaken for a person, but all have been created specifically for the purpose of performing human cognitive tasks, and thus from a technological perspective are potentially equivalent to humans in certain contexts. For example, research into artificial intelligence sponsored by the Department of Defense has led to the creation of autonomous vehicles that can navigate unfamiliar terrain without ongoing human guidance in order to remove military personnel from combat zones and therefore from harm.

Although the capabilities and durability of these prototypes remained severely limited, the use of machines to replace certain human capacities was by the early 2000s commonplace on the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan. Most of the robots and drones used by U.S. combat troops are not entirely autonomous because they are remotely linked to human operators. Nonetheless, they reflect a culturally specific approach to modern combat that stems from a societal aversion to casualties in warfare. Instead of being the inevitable result of scientific progress, the developments of robots and other automated systems in this scenario were choices. In the words of U.S. Navy researcher Bart Everett, “To me, the robot is our answer to the suicide bomber.”17

It is ironic that robots represent “our” answer to suicide bombing since suicide bombing itself was originally “their” answer to the high-technology systems deployed by Western nations and their allies during the Cold War and afterward. Indeed, most groups have expressed this notion to justify the use of suicide bombers. In the context of the Israeli-Palestinian struggle, a member of Hamas’ Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades told the journalist Nasra Hassan, “We do not have tanks or rockets, but we have something superior—our exploding Islamic human bombs. In place of a nuclear arsenal, we are proud of our arsenal of believers.”18 In an expression of the same sentiment, signs were posted at one point in classrooms at al-Najah University in Nablus and the Islamic University of Gaza that read, “Israel has nuclear bombs, we have human bombs.”19

Technology—whether “their” answer or “our” answer—is a physical manifestation of cultural values.20 When a technologically advanced state employs its most sophisticated weapons, it is not only carrying out military operations but also legitimizing its society’s value systems. Airpower in particular has come to be nearly synonymous with Western military might, not only because it allows states that employ it to project force with relatively little chance of harm to its personnel, but also because the technically sophisticated platforms of modern airpower are understood by their users to be evidence of a superior educational, research, and manufacturing capability. From this perspective, weapons are embodiments of progress.21 Their use affirms the perceived superiority of the culture that produced them and is therefore a form of psychological as well as physical warfare.

The situation is similar to suicide bombing’s tactical martyrs. Suicide bombers represent much more than a desperate effort to “throw bodies” at the technologically advanced forces of their adversaries. Their use allows an organization to invert roles, empowering themselves by portraying the mechanized forces of their adversaries as efforts to substitute machines for such human values as courage, faith, and willingness of the individual to sacrifice for the community. A senior Hizballah official wrote that one purpose of “martyrdom” operations was to expose “the Israeli soldier as one who hides in the safety of his military machines, afraid of direct military conflict.” When the journalist Barbara Victor asked a group of Palestinian children why they were not afraid of the Israelis, one replied, “Because Israeli soldiers are cowards. They have tanks and guns. They hide behind their big machines.”22

The psychological impact of airpower is so similar to the psychological impact of suicide bombing that from this perspective a discussion of both types of bombings as forms of technology is intuitive. However, the tendency to understand technology in material terms that hampered analysts prior to 9/11 seems also to have obscured the actual nature of suicide bombing. This general tendency in Western society has had the unfortunate effect of divorcing an understanding of technology from its human context.23

From a historical perspective, however, equating technology with physical devices is relatively recent in comparison with a much longer tradition of understanding technology as knowledge. The root of the word stems from the Greek tekhne, meaning “art,” “craft,” or “skill.” For centuries people understood technology as knowledge or doing, which was perfectly sensible since throughout much of human history the tools and devices at hand really were relatively simple, and it was human skill that made them useful. By the nineteenth century, European users of the term still emphasized descriptions of or teaching about the arts, especially the practical arts. By the turn of the twentieth century, this meaning began to change somewhat, and Europeans took to differentiating between “technique,” meaning procedures of working with material culture, including engineering, and “technology,” the study of such activities.24

In the twentieth century, as tools and machines became progressively more complex, and more important, as human skill was transferred to machines as a consequence of mechanization and automation, machines came to be seen as technology whose purpose was to replace rather than to complement human skill. Despite advances in machinery, automation, and control, however, the abilities of machines remained task specific and limited vis-à-vis human flexibility and creativity. Seeing machines as the sum total of technology therefore restricted dramatically how people thought about technology.25

There is, however, a well-established tradition in which technology is understood much more broadly. Leaders in the business world often define technology as an activity or a mode of problem solving that involves the mutual interaction of ideas and material devices. Peter Drucker, an iconic figure in the study of business management, drew upon comparisons with human biology to conclude that technology was about human activity, not physical things.26 Joel Mokyr began his highly regarded analysis of the modern information economy by writing, “Simply put, technology is knowledge, even if not all knowledge is technological.” He continued, “Hence useful knowledge . . . deals with natural phenomena that potentially lend themselves to manipulation, such as artifacts, materials, energy, and living beings.”27 Taking this understanding even further, Thomas Hughes defined technology as “the effort to organize the world for problem solving so that goods and services can be invented, developed, produced, and used.”28 This definition holds that much of technology—i.e., people and ideas—is intangible.

Everett M. Rogers, in Diffusion of Innovations, one of the most widely read texts about technological innovation in the business world, took a similar approach. Rogers’ definition of technology incorporates Hughes’ insight that technology is an idea or process, but also recognizes another important theme for the current analysis—control. Rogers argues, “A technology is a design for instrumental action that reduces the uncertainty in the cause-effect relationships involved in achieving a desired outcome.”29 This short definition links what technology is (i.e., ideas) with what technology is for (i.e., solving problems). In other words, technology solves problems by conferring some level of control over a given situation on its users.

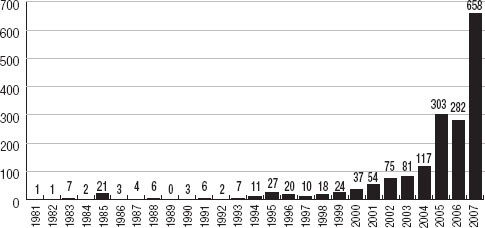

In the early 1980s, the historian Arnold Pacey published a schematic representation for an expanded, dynamic understanding of technology. He defined technology as an interactive complex consisting of three factors: a technical aspect, composed of the actual physical devices and skills used to do work and solve problems; culture and society, as expressed through goals, values, and ideas; and organizations.30 Pacey represented these three factors as the vertices of a triangle whose sides represent relationships of mutual communication and feedback. He called this interactive complex technology practice (see Figure I.2).

Source: Adapted from Arnold Pacey, The Culture of Technology (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1983), 6.

The three levels are not hierarchical, but are linked in a simple flat network in which no one factor is privileged over the others. Pacey noted that it would be facile to isolate the top vertex, the technical element, and consider it as technology in its entirety; he cautioned, however, that this would represent a severely restricted understanding. A more complete representation of technology (and thus including suicide bombing, as argued here) must integrate cultures and organizations. He concluded that any definition of technology must include “liveware” as well as hardware and summarized his model as follows: “Technology practice is thus the application of scientific and other knowledge to a practical task by ordered systems that involve people and organizations, living things and machines.”31

Acknowledging that suicide bombing is a technology allows for a multicausal explanation of the phenomenon that is much more consistent with historical reality than the single-variable explanations that have been offered to this point. Demonstrative of this approach is the popular explanation of suicide bombing advanced by Robert Pape in Dying to Win and further developed in Cutting the Fuse, co-authored by Pape and James Feldman.32 Although the two authors acknowledge the importance of multiple factors within the process of suicide bombing, in the end they offer a single-variable explanation for it: foreign occupation. Suicide bombing, they argue, is a strategic approach taken by militant groups for combating occupation by a religiously different power and is usually directed against democracies. They suggest that suicide bombing is best addressed by minimizing the footprint of occupation through an offshore balancing of forces.

This explanation is inconsistent with the complex historical reality of suicide bombing. There are, for example, conspicuous instances in which occupation has not provoked suicide bombing. Furthermore, in recent years suicide bombing has taken place in (or has been carried out by citizens of) countries that have experienced no foreign occupation, and many suicide attacks have not been directed against democracies. Also, governments that have managed to bring a halt to suicide bombing in recent years have done so not by minimizing their presence in contested territories but by intensifying their occupations and defeating their adversaries through brute force. This indicates that rather than being the primary cause of suicide bombing, foreign occupation appears to correlate strongly with the phenomenon for obvious reasons: occupations are often characterized by ethnic or religious differences that facilitate de-humanization and violence on both sides, and the occupying power often possesses greater military power than the occupied people, necessitating and legitimizing any form of resistance no matter how extreme.

Pape’s causal mechanism has therefore been greeted skeptically by many analysts familiar with suicide attacks, with Assaf Moghadam being particularly critical. Moghadam has presented a comprehensive analysis of suicide bombing that demonstrates that much of it in recent years has not been part of a national liberation strategy, has not taken place in areas suffering a direct occupation, and has not necessarily targeted democracies.33 According to Moghadam, the increase in suicide bombing from 2002 through 2007 was driven largely by the global jihadi movement centered around al Qaeda and its affiliated organizations. This movement in turn was driven by an ideology that glorifies self-sacrifice and martyrdom and resulted in a global diffusion of suicide attacks in which militants with an ideological commitment to self-sacrificial violence spread suicide bombing around the world.

Moghadam’s analysis takes a multi-causal approach in explaining suicide bombing, emphasizes the importance of radical ideologies in driving the global jihadi movement, and makes a powerful case for understanding recent suicide bombing as being different from older, more localized suicide bombing, but at the same time tends to view ideologies as being fixed rather than changing in response to external stimuli. As Thomas Hegghammer has noted, incarnations of jihadi ideology in the early 1990s produced far fewer suicide bombings than did later periods, so clearly something changed within the movement and within the ideology causing it to shift in emphasis toward self-sacrificial violence. It seems clear that what is needed is an integration of Pape’s emphasis on external political and military factors and Moghadam’s focus on internal factors, such as ideology.34

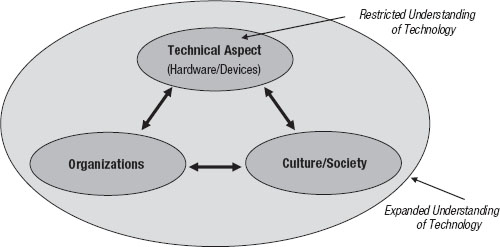

Approaching suicide bombing as a technological system allows for integrating these explanations through a well-established method (see Figure I.3). Suicide bombing, like all technologies, is the product of interactions between internal cultural factors and external pressures. These interactions constitute the dynamic relationships that connect the vertices of the technology practice triangle. External pressures, such as foreign occupation, create the problems or challenges that a particular culture hopes to solve; in other words, they create the culturally specific “necessity” for a solution to a problem. The well-known saying “necessity is the mother of invention” describes this driver of innovation but also oversimplifies the matter because technologies satisfy subjective desires more so than they do any universally recognizable objective need.35 A subtle distinction, perhaps, but grasping that perceived “need,” rather than objective need, drives innovation allows for an understanding of why different cultures identify different problems that “need” to be solved.

FIGURE I.3Modified Model of Technology Practice

Source: Adapted from Arnold Pacey, The Culture of Technology (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1983), 6.

Possibility encompasses internal factors—ideas, skills, and devices—that a culture has at its disposal for solving a particular problem. Novel technologies do not emerge spontaneously. Instead, they result from the reconfiguration and modification of existing technologies and ideas, so what a culture is capable of achieving in terms of technology depends upon what it has already achieved.36 The knowledge and devices available to a given culture circumscribe how that culture attempts to solve its problems. For a culture without a manufacturing capability, using conventional cruise missiles is an impossibility; suicide attackers, however, may be a viable option if the culture’s ideology views self-sacrifice as admirable.

The interplay of cultural factors and external pressures explains the underlying similarities in the development of suicide bombing by different organizations. The differences in the way groups recruit and deploy their suicide attackers are, however, so significant that they led Mohammed Hafez to suggest that a generalized theory of suicide bombing cannot be proffered.37 To explain these differences, one must integrate a third factor of technological systems: use. In this context use takes the form of management and training of potential recruits in addition to their deployment in the course of their missions.

Use is an essential element of technology, but the way that differences in use produce significant local variations in the basic, underlying technology is often underappreciated. Different users may use the same technologies differently, but more important, as they use technologies, they change them. Effective users often find new ways to employ old technologies. Use is an opportunity for learning and experimentation, so the world of use is a source of constant innovation and reinvention.38 A full understanding of suicide bombing therefore must integrate need and possibility as well as use.

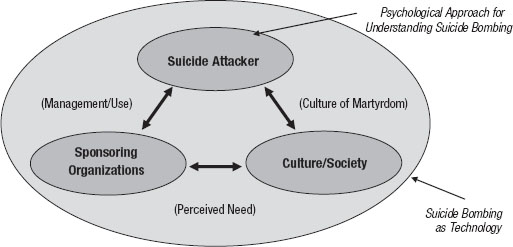

Assessing suicide bombing through the modified model of technology practice is therefore relatively straightforward, as the organizations and cultures that promote suicide bombing fit well within the corresponding vertices of the interactive triangle (see Figure I.4). The only major cognitive leap is accepting the replacement of the technical element of the system with the human suicide attacker. Making this substitution allows one to examine the individual psychological motivations of suicide attackers independently of the shared social meanings of the technology present at the organizational and cultural levels. It also allows for an examination of the dynamic relationships between all three vertices.

Many analysts hesitate to make a sharp distinction between suicide bombing and other forms of high-risk combat missions. For example, nearly all of them consider the Assassins, a radical sect of Shiite Muslims active circa 1000–1200 CE, to be antecedents of today’s suicide bombers because the assassins inevitably faced a high probability of death in carrying out their missions, and many seem to have desired to die. Viewing high-risk attacks as precedents for suicide bombing is problematic for two reasons.

FIGURE I.4Suicide Bombing as Technology Practice

Source: Adapted from Arnold Pacey, The Culture of Technology (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1983), 6.

First, high-risk operations are common throughout the history of combat. Why not also include the Spartans, who willingly fought to the death at Thermopylae, in the list of historical precursors to suicide bombing? Inevitably any effort to contextualize suicide bombing historically by presenting it as a form of high-risk attack will be either selective and idiosyncratic or so broad as to be of little use. Second, such a genealogy of suicide bombing obscures one of the most important realities of contemporary suicide bombing: the extent to which the circumstances surrounding the death of the individual have moved from the individual to the organization sponsoring the attack. This is a consequence of the introduction of explosives to high-risk missions, which in turn compressed two previously distinct events—the success of the attack and the subsequent death of the attacker—into one inseparable act. By making the death of the individual attacker the objective of the mission, suicide bombing has taken an event that historically was the result of the individual’s actions and choices in the highly uncertain realm of combat and made it a certainty predetermined by the mission. This certainty has come at the expense of individual choice during the mission and has necessitated the social and cultural programming that characterizes suicide bombing, which in turn explains why suicide bombing is rarer than high-risk missions.

The definition of suicide bombing offered here is therefore a functional definition based on how the human bomber is used by the organization responsible for his or her attack. Such an emphasis on function presumes that suicide bombers are not agents of violence and should not be considered users of the weapons they direct. Rather, they are agents of control. It is their intelligence—their ability to recognize and respond to the environment in real time, to discriminate, and to make decisions—and not their fighting ability that contributes to the effectiveness of the weapon and to the potential success of the mission. Thus, for the purposes of this book, a suicide attack is defined as follows: an instance of organizationally directed violence that utilizes at least one human being for purposes of weapon guidance and control that necessitates the death of the attacker(s). Suicide bombing, in turn, is the social process through which suicide attackers are made. The term “suicide” is appropriate because in most instances of this type of attack there is conclusive evidence in the form of written or videotaped testimonials that the decision to carry out lethal self-violence was made with the understanding of the attacker and was anticipated by him or her.

“Guidance and control” may or may not include the actual detonation of the device, so the definition also applies to the so-called remote-control martyrs who are used to guide a weapon to a particular location, at which point the weapon is detonated remotely without the consent or anticipation of the bomber. Although technically not suicide, from a functional perspective the two cases are identical. In both instances, human intelligence is used to direct a weapon to a target, and the death of the bomber is necessary and anticipated from the perspective of the user, that is, the sponsoring organization. Since the only factor that differentiates these attacks from suicide bombing more generally is the intent of the bomber, it is difficult to gauge fully the extent of this phenomenon, as such attacks have undoubtedly taken place numerous times since they were first documented in the mid-1980s.39 These operations make use of human intelligence for tactical purposes, but they are generally understood as being manipulative in the extreme, so they cannot exploit the strategic, legitimizing elements of voluntary self-sacrifice, thus making them less effective and less numerous than “regular” suicide attacks.

The definition of suicide bombing presented here excludes other forms of high-risk attacks, including “no-escape” attacks, in which a person opens fire with the intention of provoking a lethal response and then fights to the death. There are similarities, of course. In the Palestinian context, the attackers, their organizations, and society tend to recognize both forms of attack as belonging to the broader category of istishhadia, or martyrdom. Recruitment and preparation for both kinds of missions, including the completion of martyrdom statements and videos, are also similar.40 Nevertheless, significant differences would appear to require classifying no-escape missions separately. In these types of operations, the death of the attacker is de-coupled from the execution of the attack and is therefore not always necessitated by the attack. In addition, the death of the attacker is not self-inflicted. Although the attacker may well desire death, professing the desire to die and possessing the capability to commit lethal self-violence are two very different mental states. Since the death of the attacker in a no-escape attack is neither required nor self-inflicted, there is a degree of freedom that is not present in suicide bombing.41

The mutual interplay between people, ideas, and devices within technology practice invalidates one of the primary assumptions underlying the above-mentioned simplified definitions of technology as gadgets—that technology is at its heart applied science, i.e., rational, logical knowledge put to use for the purpose of solving problems. It follows from this assumption that technology should be a rational process. For many in the West with a “technology as gadgets” perspective, technology is an inherently progressive means by which scientific knowledge takes physical form and diffuses from the scientific elite to the masses.42

This is a powerfully held preconception regarding technology today and is likely to be leveled against the argument that suicide bombing, which many refuse to recognize as being either logical or rational, is a technology. There are two counter-criticisms to this argument. First, there is a brutal logic to suicide bombing when one views the phenomenon from the organizational level. Suicide bombing can, indeed, be rational in power-political terms. Second, technologies are elements of specific human cultures that have no obligation to be rational or logical. That is, the presence of irrational elements in a given system does not disqualify it as a technology and does not preclude the presence of rational elements in the same system.

The complexity of technology practice allows for the possibility that different elements of the same technological system can be simultaneously rational and irrational, rendering any judgment as to the rationality of the entire system problematic. Rational means can be put to the most irrational of ends, and irrational motivations can sometimes lead to rational action.43 Both occur in suicide bombing. Although there is often logic at the organizational level, the motives of individual bombers vary widely, ranging from the logical—such as securing financial support for family members as a result of carrying out a bombing assignment—to the much more emotional and irrational, including revenge and empowerment. The result of many suicide bombings, the indiscriminate slaughter of noncombatants, suggests that the entire enterprise is irrational, but this brutality can pay off rationally in the form of coercive political power. In a sense, then, both impressions about suicide bombing are correct: it is rational, and it is irrational. Suicide bombers are therefore consistent with weapon technologies more generally, for weapons have always been a fusion of rational utility and irrational cultural, psychological, and aesthetic factors.44

Suicide bombing integrates living and nonliving elements to create a relatively inexpensive weapon that nevertheless is intelligent in the truest sense. This integration of living (including human beings) and nonliving, like the integration of rational and irrational, is common in technological systems. Animals and plants were domesticated and integrated into the large-scale technologies of husbandry and agriculture, which ultimately made settled human existence possible. The use of living things is therefore among the oldest and most significant elements of technology.

Furthermore, throughout history human beings have been included in technological systems so that one group might be exploited and used by another. The most common human use of human beings is slavery. Although its precise form has varied over time and among cultures, slavery—the use of involuntary human labor—is a technology whereby human beings are used by others because of their ability to work, think, or other-wise act on materials and assist in creating goods, products, or services for human consumption. No less a figure than Aristotle stated, “A slave is property with a soul,” a “living tool.” He compared human slaves to draft animals and concluded that “the use of domestic animals and slaves is about the same; they both lend us their physical efforts to satisfy the needs of existence.”45 The technology of slavery resulted from a mental innovation rather than a physical one—the perception that not all human groups are equal. This mental construct made slavery possible by allowing one group of humans to cast another group as being less than human and therefore making the latter acceptable for use by the former.46 Once this step was taken, the forced domestication of humans proved to be no more troubling to the conscience of the slaveholder than the domestication of animals had been to the farmer. Slavery has contributed historically to more large-scale construction projects than has any other form of power.

Human mental labor, not just physical labor, can also be exploited in technological systems. For nearly two and a half centuries, from the first recorded use of the term “computer” in 1646 until 1897, the tedious, repetitive calculations known as scientific computation, or as it is called today, data processing, were done by human beings, who were called computers.47 The Oxford English Dictionary’s first definition for “computer” is “One who computes; a calculator, reckoner; spec. a person employed to make calculations in an observatory, in surveying, etc.” The term was first applied to a mechanical calculating device in 1897. Only in 1946 was the term applied to ENIAC, the first large-scale, general-purpose electronic computer.

By the late 1800s, people were being used as components within extremely sophisticated computational systems. Teams of people served as living calculating machines to carry out the numerical computations increasingly required by scientific and military projects. Managers broke down tasks into discrete steps and then presented these steps to the “computers,” who calculated repetitive mathematical computations by hand, eventually providing management with tables of processed data. In the years before electronic computers, human beings interfaced with mechanical devices in an increasingly professionalized and mechanized bureaucracy.48 By World War II human and machine elements had been integrated into hybrid control systems in which the human and machine elements were both engineered and modified to improve system performance. Harold Hazen, an engineer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, summed up this approach in a memo to Warren Weaver, who at that time sat on the National Defense Research Committee: “This whole point of view of course makes the human being . . . nothing more or less than a robot, which, as a matter of fact, is exactly what he is or should be.”49

By the 1960s, human beings were still being used in sophisticated control and computational systems, but they were increasingly becoming redundant design elements, that is, backups to be used in case the electronic computers failed, not primary computational elements. NASA engineers thought in these terms.50 Their counterparts in the Soviet Union took this train of thought further, to the point that they began to use machine terms to evaluate potential cosmonauts and to engineer people through conditioning to fit into mechanical systems. A Soviet cybernetics specialist, Igor Polatev, asserted that repetitive training was the key to mechanizing people and thereby avoiding human error. He wrote, “The less his various human abilities are displayed, the more his work resembles the work of an automaton, the less [the human operator] debates and digresses, the better he carries out his task.” For their part, Soviet cosmonauts protested the “excessive algorithmization” of their behavior.51

The suggestion that suicide bombing is a control technology draws on a long history of the human use of human beings, particularly as data-processing centers in technological systems. Although in many contexts silicon-based electronics or hardware guided by software have innumerable advantages over people, in certain other contexts, human liveware offers a relative advantage. This is especially true in suicide bombing, because by substituting human beings for electronic computers, suicide bombing provides a dramatic increase in efficiency by charging its human computers with tasks for which they are well-suited, such as visual recognition, discrimination, and decision making. Computers are still not very good at these kinds of tasks; a child can easily beat the most sophisticated computer program when it comes to such seemingly simple tasks as the recognition of human faces.52

The organizations that deploy suicide attackers restrict the bombers’ behavior in significant ways to ensure that they will carry out their missions as planned. Limiting the freedom of the individual involves stripping away alternatives and leaving only a narrow mission scenario as the socially acceptable range of actions for the individual or individuals. This behavioral compression is the true technological innovation of suicide bombing—limiting the behavior of certain human beings so that they can be used reliably by other human beings.

There is ample precedent in which a set of routines transforms the nature or behavior of an agent into a form of technology, even if the set of routines itself is completely immaterial. Brian Arthur cites digital compression algorithms as such a form of technology.53 The best-known digital compression algorithm is probably the one that produces the MP3 audio file format, which greatly reduces the size of audio files. Such algorithms are a significant part of the technology of digital music and video storage and transmission—without which a huge portion of the consumer electronics market could not exist—yet the algorithms, by their very nature, are completely invisible, executing their operations without altering the content of their subject files in any significant way.

Whereas the purpose of the MP3 algorithm is to compress the size of audio files, the purpose of suicide bombing is to compress the space for behavioral possibilities available to individuals or small groups of individuals. Organizations that deploy suicide attackers have therefore developed behavioral compression algorithms that allow them to influence the actions of some of their followers in a systematic manner. Various groups have developed different algorithms based on their cultures and symbols, but in all cases repetition of a relatively simple message—self-sacrifice for the group—from a number of different and mutually reinforcing sources limits the behavior of the prospective bomber, much as the repetitive training of the Soviet space program was meant to limit and “algorithmize” the behavior of cosmonauts.

The suggestion that suicide bombing is a form of control technology is thus consistent with other instances of the use of humans as control elements in technological systems. Such a turn of events would undoubtedly have horrified Norbert Wiener, one of the founders of cybernetics, an inter-disciplinary control science that emerged from World War II antiaircraft fire control systems. For Wiener, any system of control, social or otherwise, that reduced human possibilities by constraining and mechanizing the actions and thoughts of people was to be avoided. In 1950 he wrote, “I wish to devote this book to a protest against this inhuman use of human beings; for in my mind, any use of a human being in which less is demanded of him and less is attributed to him than his full status is a degradation and a waste.” He continued, “Those who suffer from a power complex find the mechanization of man a simple way to realize their ambitions.” He considered such behavior to be “a rejection of everything that I consider to be of moral worth in the human race.”54

Wiener’s misgivings reflect an apprehension toward technology and the modern world that has been shared by critics on the right and the left of the political spectrum, namely, the fear that technology will reduce humankind into raw material for technological processes and human relationships into transactions. Suicide bombing incorporates both these transformations. Individual recruits form the material basis for guidance and delivery systems for weaponry and are discarded when the weapons fulfill their functions. Individual relationships—with family, community, and deity—are likewise transformed into the programming steps necessary to persuade the bomber to behave in a calculated manner, which by design strips away individual choice and freedom. From this perspective, suicide bombing, used so often by groups that fear and reject the modern world, is a quintessentially modern technology that pushes the disenchanting and de-sacralizing elements of the modern world to their limits.

The Business of Martyrdom: A History of Suicide Bombing consists of three sections that correspond to the life cycle of technological systems—innovation, during which new technologies are developed; diffusion, during which technologies spread and are adapted to new environments; and commodification, during which previously rare technologies see regular use and come to be distinguished in a crowded market through marketing and branding. In the first section, concerning innovation, Chapter 1 analyzes the invention of a primitive form of suicide bombing in Imperial Russia, in particular the cultural, organizational, and technical antecedents that made self-sacrifice potentially useful as a form of control technology. Chapter 2 examines the early history of suicide bombing, focusing on its reemergence in war-torn Lebanon and the role played by revolutionary Iran. Chapter 3 looks at the spread of suicide bombing from the Middle East with an emphasis on the importance of use in shaping the technology in new cultural contexts. Its focus is the independent reinvention of suicide bombing by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in their effort to carve an independent state for the Tamil people out of territory currently integrated into Sri Lanka.

In the second section, discussing diffusion, Chapter 4 presents a well-known model of technological diffusion and applies it to the experiences of the Provisional Irish Republican Army and the Workers’ Party of Kurdistan, two groups for whom the diffusion of suicide bombing was problematic. Chapters 5 and 6 discuss the diffusion of suicide bombing to the Israeli-Palestinian struggle, an especially important case study because of the quantity of analytical work that has been produced regarding Palestinians’ use of the technology. In its early stages, covered in Chapter 5, Palestinian suicide bombing was improvised and inefficient. In the mid-1990s, practice, failure, and the direct transfer of know-how from Hizballah led to the refinement and controlled use of suicide bombing for a political goal. As suicide bombing became more socially acceptable, and as individuals began to seek organizations to assist in their desire to take part in suicide attacks, it became much easier for them to be carried out by small, relatively autonomous groups. This newer organizational dynamic drove the suicide bombing of the second intifada. Local actors and groups initiated these attacks more than centralized organizations did, but the operations conformed in broad terms with the goals and motivations of these larger organizations. The Palestinians therefore provide an illustrative case of the interaction of the top-down and bottom-up dynamics that came to characterize much of global jihadi suicide bombing in the new millennium.

Chapters 7 and 8, in the third section, on commodification, explore a new trend in suicide bombing—its spread from one area to another via the ideology and personnel of the global jihadi movement. The conclusion of The Business of Martyrdom examines the reasons for the decline in suicide bombing from 2008 to 2010 by exploring a fundamental tension that emerges through the use of human bombers—reconciling organizations’ systematic use of them with the freedom necessary to make martyrdom authentic to a broader audience. The tactical and strategic dimensions of martyrdom are fundamentally at odds with each other, and poor management of this contradiction has made globalized suicide bombing difficult to justify socially and may well have diminished its appeal to groups with a local agenda.

This historical analysis of suicide bombing offers several lessons about technology more generally. First, relatively simple technologies can provide advantages over more sophisticated technologies provided they are integrated into their human, social, and cultural contexts. Second, the effectiveness of a given technology at the tactical level need not necessarily generate strategic advantage. Third, single variable explanations are insufficient for understanding suicide bombing or, indeed, any technology. Instead, technology should be understood as a complex, ongoing process involving people, ideas, and machines.