Palestinian Suicide Bombing in the 1990s

In 1992 members of Hamas, then a relatively new Islamist organization with its stronghold in the Gaza Strip, attempted what at that time was an ambitious form of attack against Israel.1 Several members of the organization had booby-trapped a car with explosives in a suburb of Tel Aviv with the hope of inflicting a large number of civilian casualties. Security forces, however, found the car and were able to disarm the explosives.

After this failure, members of the group apparently decided to follow the example of Hizballah and integrate a human with a bomb to ensure a more reliable detonation.2 In April 1993 Yahya Ayyash, a Hamas explosives expert who came to be known as “The Engineer,” rigged a Volkswagen with an improvised hodge-podge of explosives taken from other weapons. A young man named Saher Taman al-Nabulsi drove the car to the target, a highway rest stop near Mehola Junction. Saher had been involved in the failed attack of the previous year and was wanted by Israel for the murder of two Israelis. He apparently decided to become Hamas’ first human bomb rather than continue to face arrest or death at the hands of Israeli authorities. He drove the rigged vehicle between two buses with Israel Defense Force (IDF) personnel inside and detonated the explosives. In some ways the results were amateurish. The blast was relatively weak and was deflected upward by the two buses; twenty soldiers and one civilian were injured, and the only fatalities were Saher and a Palestinian who worked at the rest stop.3 The militants learned from the attack, however, and future suicide missions would prove to be far more deadly.

The improvised manner in which suicide bombing became part of the Israeli-Palestinian struggle more than a decade after being developed in Lebanon is consistent with the broader model of technological diffusion discussed in preceding chapters. As the above example shows, unsophisticated trial runs can be relatively easy to stage. Hamas’ early use of suicide bombing was haphazard and ineffective. In the mid-1990s, trial and error, as well as the direct transfer of know-how from Hizballah, allowed Palestinian Islamists to master suicide bombing and to use it in a manner similar to that of the Tamil Tigers: the controlled, calculated use of suicide attacks to inflict harm, intimidate adversaries, and to send a message about the sponsoring groups’ identity and intentions.

The Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, while inadvertently contributing to the rise of Hizballah, succeeded in its intended purpose of destroying the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) as a conventional military organization and driving it from southern Lebanon. The upper ranks of the PLO eventually settled in Tunisia, leaving behind a movement and a people without an effective organizational means for pursuing Palestinian statehood. While the PLO leadership occasionally staged irritating raids against Israel, for the most part it was isolated from the reality of Palestinian life under Israeli occupation and developed a reputation for materialism and corruption.4

In the occupied territories of the 1980s a deceptive calm masked tension building under the surface. This tension exploded into a systematic campaign of civil disobedience, strikes, and demonstrations throughout the occupied territories beginning in December 1987.5 The spark of the uprising, the accidental deaths of several Palestinians caused by a careless Israeli truck driver, was less important than the root cause of the rebellion—a deep sense of frustration and humiliation felt by Palestinians. The uprising, or intifada, came to serve two purposes.6 First, in the words of the Palestinian scholar Sari Nusseibeh, the intifada “exorcised demons of humiliation, inferiority, and self-contempt” from nearly two million Palestinians living under Israeli occupation. Second, it allowed a young, indigenous Palestinian leadership the opportunity to mobilize this discontent and direct it toward a more coherent end—Palestinian statehood.

Local leaders from the factions of the PLO formed the National Unified Command, which wrote and distributed leaflets instructing Palestinians on ways to resist the occupation, limited the armed conflict (for instance, by calling for an end to the use of Molotov cocktails), coordinated general strikes and other protests and activities in the occupied territories, and of great significance, maintained pressure on the Israeli government for several years. This ongoing pressure eventually made resolution of the Palestinian situation an important domestic issue in Israeli politics and engaged the United States as a potential broker in any peace process.

The intifada took the PLO leadership in Tunis by surprise, but as the uprising continued it became clear that recognized leadership would be necessary to turn the pressure of the intifada into concrete political gains. From exile in Tunisia, PLO chairman Yasser Arafat seized the opportunity, and over the next several years the PLO, representing the interests of Palestinians in the occupied territories, recognized Israel and renounced terrorism, helping to initiate a formal dialogue with Israel, beginning with the Madrid conference in October 1991. After some false starts, the two parties made significant progress in Oslo, Sweden, during secret negotiations that were publicly affirmed when Arafat and Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin shook hands on the White House lawn in September 1993. The two agreed to a Declaration of Principles stating that much of the Gaza Strip and parts of the West Bank would be transferred to Palestinian administration, giving more than one million Palestinians a measure of control over their daily affairs. The following year, through an agreement signed in Cairo, the Palestinian Authority (PA) was created to serve as the administrative instrument for Palestinian self-governance. Arafat assumed leadership of the Palestinian Authority, adding the title president of the Palestinian Authority to his positions as chairman of the PLO and leader of Fatah, the dominant faction in the PLO.7

The peace process, however, was flawed from the beginning, and in retrospect it is clear that the partial successes of the early years stemmed entirely from deferment of fundamental issues to a later date. The Oslo-Cairo process dealt with Palestinian self-governance, but did not address the long-term issue of a Palestinian state. The administrative and legal status of Jerusalem remained unresolved as did the Right of Return of Palestinian refugees (and their descendents), allowing them to go back to their pre-1948 homes, now in Israel.8 Successive Israeli governments accelerated construction of settlements in the West Bank during the 1990s, throwing into question the credibility of Israel’s stated intentions to exchange land for peace. Furthermore, Arafat’s willingness to make the compromises necessary for a lasting peace also remained an open question.9 Finally, Arafat and his Fatah associates returned to a different and much more divided Palestinian community than the one they had left a decade earlier. Years of occupation and the ineffectiveness of the PLO had led to the emergence of an Islamist movement for Palestinian liberation whose leaders were not beholden to the PLO and its program of secular nationalism and who were much less prone to compromise.

Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad took shape in the late 1980s, but they were the product of decades of opposition to the perceived encroachment of Western politics and values into the Middle East. After World War I, when Western powers partitioned the lands formerly controlled by the Ottoman Empire, many Arabs living there sought an alternative to Western culture and governance. By the late 1920s, some of them appeared to have found it in the form of political Islam. In 1928 in Egypt, Hassan al-Banna founded the Society of the Muslim Brothers, also known as the Muslim Brotherhood. Banna was concerned about the retreat of Islamic civilization and cautioned his followers that nominal political independence was worthless without intellectual, social, and cultural independence.10

A Palestinian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood was established immediately after World War II and participated in a limited fashion in the 1948 war against Israel. After the war, Gaza was administered by Egypt. Egyptian governments had over the years suppressed the Brotherhood and extended this treatment to Gaza, a policy that encouraged underground militancy. The group could operate somewhat more freely (and was consequently less militant) in the West Bank, which at the time was administered by Jordan. When Israelis captured Gaza and the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) during the 1967 war, the local branches of the Muslim Brotherhood reacted by intensifying their activities and creating an infrastructure of social support services. In 1978 the Muslim Brotherhood founded the Islamic University, which has been the principal stronghold of it and its successor organizations in Gaza ever since.11

In the occupied territories, Palestinians became increasingly frustrated by the PLO’s lack of success in ending the occupation. Islamic groups aggregated around mosques and universities and developed a vague organizational framework, but they did not challenge the occupation openly. Their relationship with the PLO, Fatah in particular, was often adversarial. The desire to avoid a split within Palestinian society encouraged coexistence, but major ideological differences led to skirmishes between supporters of Fatah and of the Islamic groups in the 1980s.12

The intifada provided the impetus for the Gaza branch of the Muslim Brotherhood to transform itself into Hamas, formally the Islamic Resistance Organization, for which “Hamas” is an acronym and in Arabic means “zeal” or “enthusiasm.” In the days following the outbreak of the intifada, several leaders of the Muslim Brotherhood in Gaza, including Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, acknowledged as the founder of Hamas, met to discuss the situation. Understanding that the intifada’s grassroots opposition to Israeli occupation was something fundamentally new, they decided to play a much more active role in the resistance.13 Members of Hamas did not participate in the National Unified Command of the intifada, however, but kept their independence, drawing upon the movement’s history as an educational and social phenomenon to present Hamas as an Islamic alternative for leadership toward Palestinian statehood.14

Yassin and the others articulated the goals of Hamas in its charter, released in 1988. In the document, the leadership of Hamas declares that the land of Palestine and the Islamic faith are inseparable and that to cede one inch of Palestine, which for them stretches from the Mediterranean Sea to the Jordan River, is not permissible (see especially articles 11 and 12).15 Although Hamas began as a relatively nonviolent movement—in the 1970s and early 1980s the Israeli government had been supportive of the Islamists as an alternative to the PLO and did not designate Hamas as a terrorist organization until eighteen months after its official founding—the group’s charter clearly defines Hamas as a military organization that rejects peaceful resolution of the Palestinian issue. The charter also recognizes the PLO as a “father, brother, relative, and a friend,” but then goes on to differentiate Hamas from the PLO based on the latter’s secular nature: “Therefore, in spite of our appreciation for the PLO and its possible transformation in the future, and despite the fact that we do not denigrate its role in the Arab-Israeli conflict, we cannot substitute it for the Islamic nature of Palestine by adopting secular thought. For the Islamic nature of Palestine is part of our religion, and anyone who neglects his religion is bound to lose.”

In its early years, Hamas as an organization had to reconcile a number of mutually opposing tendencies. Its leaders had to distinguish themselves from groups such as Fatah, but not to the point of Palestinian civil war. Much of Hamas’ legitimacy stemmed from its credibility as a resistance group, but pushing an uncompromising Islamic war for the liberation of all Palestine too strongly would have threatened its most important source of appeal to the Palestinians—its growing network of charitable and social institutions. Thus Hamas’ reputation as a scrupulous and fair social welfare organization put limits on its militancy. Consequently, the uncompromising nature of the charter was offset somewhat in practice by a degree of pragmatism and flexibility on the part of Hamas.16

Even more ideological and less prone to pragmatic accommodation than Hamas was Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), which also grew from the Gaza branch of the Muslim Brotherhood. The founders of PIJ were inspired by the Islamic revolution led by Ayatollah Khomeini in Iran. The primary ideological difference between Hamas and PIJ was that the former existed as a specifically Palestinian movement while the latter began as a catalyst for Islamic revolution throughout the Arab world. Personal agendas and animosities among rival leaders served to put distance between the two groups as well. PIJ, as a smaller group with fewer resources and obligations than Hamas, has not demonstrated any of the tendencies toward accommodation that Hamas has shown.17

The Dome of the Rock, a shrine built to commemorate the site from which Muhammad ascended to heaven, and the nearby al-Aqsa mosque stand in the heart of the Old City of Jerusalem. These two holy sites constitute the centerpieces of a thirty-five-acre complex of buildings and gardens called the Haram al-Sharif (Noble Sanctuary) by Muslims. The Haram al-Sharif is believed by many in the Jewish and Christian communities to have been built upon the remains of the Temple of Solomon, destroyed and then rebuilt more than two millennia ago, and is thus the holiest site for Jews. The faithful believe that it is the point from which the world unfolded during the creation and is the place where God created Adam.18 Faithful Jews refer to the site as the Temple Mount.

In August 1990 the leader of a conservative Jewish group called the Temple Mount Faithful announced a plan to lay a foundation stone for the Third Jewish Temple on the Mount, which would have symbolized the recapture of the site for the Jewish community. Leaders of Hamas interpreted the announcement as a threat and called for demonstrations. As the day of the ceremony approached, scuffles between Palestinians and Jews became a regular occurrence. On the morning of October 8, large crowds gathered, and some of the Palestinians began pelting Israeli police and Jewish worshippers with stones and bottles. The police responded with gunfire, killing twenty-one Palestinians and wounding nearly a hundred. Thirty-four Israelis, including police, were injured.19

The Hamas leadership responded by calling for its own jihad against the Israelis and began organizing a military wing, the Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades.20 This new wing took its name from Sheikh Izz al-Din al-Qassam, a Palestinian from Haifa who had led an insurrection in Mandate Palestine, assassinating British officials and Jewish civilians in the early 1930s before being killed by the British.21 The emergence of the al-Qassam Brigades corresponded with an increase in lethal knife attacks on Israelis. Within two months, eight Israelis were murdered in such a fashion.22 The stabbings continued for the next two years and increasingly were carried out by members of Hamas. This “War of the Knives” lasted until December 1992, ending when Hamas members killed six Israeli soldiers in two separate attacks and kidnapped a seventh, Sgt. Maj. Nissim Toledano, to use as a bargaining chip. After negotiations between the Israeli government and Hamas broke down, Toledano was murdered and his body found in a ditch on December 15.23

Israeli prime minister Rabin then arrested more than a thousand members of Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad and attempted to deport 415 of them to Lebanon. The Lebanese government refused to accept them, so they began 1993 in makeshift camps in Israeli-occupied southern Lebanon, near the Israeli border. Hizballah, however, accommodated the militants during their exile. During this time, Hizballah undoubtedly instructed these Palestinians in the strategies and tactics of resistance, including providing advice on how to organize and carry out suicide attacks.

The deadly attacks of late 1992 were unusual in comparison to the overall level of Palestinian violence against Israelis during the intifada. In the early stages of the uprising, the leadership of the Unified Command had deliberately tried to keep Palestinian actions non-lethal, advocating and instructing on acts of civil disobedience in its leaflets. The Palestinians had access to a small number of guns, but purposely did not use them in their confrontations with Israeli forces. Regardless, Palestinian youths throwing stones and being shot at by Israeli soldiers created a public image of the intifada as one of Palestinian violence, though their collective actions generally involved non-lethal, civil disobedience. Restrictions on the use of deadly violence did not, however, extend to affairs within the Palestinian community. As events unfolded, another dimension of conflict emerged—that of intra-Palestinian strife and competition in which violence would become far more deadly than Palestinian violence directed against Israel.

The struggle within the Palestinian community resulted in part from the withdrawal of Israeli security forces from many parts of the occupied territories in late 1987 and early 1988. In the freer and more lawless environment, paramilitaries from the various Palestinian factions competed with one another to establish order and primacy. It was especially important for Hamas, as a relatively new organization that had not formally taken part in the leadership of the intifada, to distinguish itself. Even before they began to target Israelis, members of Hamas had been killing and intimidating Palestinians to carve out a secure operational space and establish their credentials as a legitimate Islamic police force. For Hamas leaders, “purifying” the Palestinian community in such a manner was essential. During the 1980s, collaboration with Israeli security forces had become widespread, with thousands of Palestinians informing on their neighbors. As early as 1982–83, the Organization of Jihad and Da’wa had been created as a new body within the Gaza Muslim Brotherhood to root out, arrest, interrogate (sometimes brutally), and kill suspected collaborators. The members and cells of this body would several years later form the nucleus of the al-Qassam Brigades. 24

During the intifada, Islamic morality became one of the first areas into which Hamas extended its self-appointed right to judge and punish. Hamas leaders believed that an abandonment of Islamic morals had weakened the Palestinian community, so they sought to impose and enforce conservative Islamic social values on it. To this end, Hamas members carried out numerous “honor killings”—executions of Palestinian women judged to have transgressed standards of moral conduct through their behavior. According to B’Tselem, the Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories, more than a hundred women were executed for moral crimes during the period of the intifada. Many of these executions were carried out by Hamas, some by the al-Qassam Brigades.25

All the paramilitaries targeted suspected informers within their midst, but Hamas was particularly thorough and brutal. They staged dozens of public show trials in which suspected informers (as well as those accused of common criminal offenses) were tried and sometimes publicly executed. The number of collaborator killings among all Palestinian groups in Gaza increased from 1 in 1987 to 199 in 1992. B’Tselem credits Hamas with 150 such executions during the course of the entire intifada, from 1987 to 1993.26

Today, many observers assume that Hamas’ legitimacy in the eyes of its followers stems from its uncompromising stance toward Israel, but Hamas first took a hard line with its own community. Initially its legitimacy stemmed from its members’ ability to protect their community by purging it of internal enemies.27 The violence directed against Israelis was the consequence of a more confident and established Hamas turning its militant groups toward external rather than internal threats.

The Cairo-Oslo process polarized Palestinian paramilitaries. Fatah and its affiliates joined the peace process and eventually became a legitimate security force through the PLO’s role in the creation of the Palestinian Authority with a mandate to police the community. It could therefore continue to use violence, but now it was legally sanctioned. Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, unable to legitimize themselves through politics, continued on the path that had brought them through the intifada—using violence to establish their credibility and to undermine their adversaries. The legitimacy granted to Fatah by the Cairo-Oslo process meant that Hamas and PIJ needed to escalate their campaigns to continue distinguishing themselves through force. In this light, intra-Palestinian violence during and following the intifada, the first lethal attacks directed against Israelis, and eventually the use of suicide attackers can all be seen as part of a continuum of escalation, as these groups sought more powerful weapons to make the kinds of political statements that they could not make in any other way without sacrificing their principles and identities.

On September 13, 1993, when Yasser Arafat and Yitzhak Rabin signed the Declaration of Principles, they validated a peace process begun in secret meetings in Oslo the previous year and marked the formal conclusion of the intifada. Hamas saw the Declaration of Principles as an existential threat because it committed the PLO to a political program that it could not accept.28 An implication of the Declaration of Principles and the creation of the Palestinian Authority was that Fatah would be responsible for combating terrorism and helping to secure Israel. This aspect of the arrangement effectively guaranteed armed conflict among Palestinian factions.

Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad responded to the signing of the Declaration of Principles with an escalation of violence that for the first time included the repeated use of suicide attackers. On the eve of the signing, Hamas guerrillas ambushed and killed three Israeli reservists, and a Palestinian carrying Hamas leaflets stabbed a bus driver to death before being fatally shot himself. In what may well have been another failed suicide attack, a Palestinian driver was killed when his vehicle collided with an Israeli bus. The car had been booby trapped with containers of gasoline and propane, suggesting that it was meant to explode upon collision.29 The bomb did not detonate, so only two people on the bus were injured. The following month, another Hamas member, twenty-year-old Kamal Bani Odeh, rammed an Israeli commuter bus and detonated his vehicle, killing himself and injuring thirty passengers. As had been the case in previous attacks, the lack of Israeli fatalities can be attributed to the poor technical preparation of the attack. Odeh’s vehicular bomb consisted of gasoline, hand grenades, and nails meant to serve as shrapnel, all of which destroyed the car and charred the side of the bus, but did not produce the powerful blast necessary to cause additional fatalities.30 In all, there were seven attempted suicide bombings in the fall and early winter of 1993, five attributed to Hamas and two to Islamic Jihad; none of them caused fatalities apart from the bombers themselves.31 These failures reflect the haphazard, improvised way in which suicide bombing was imported into the Palestinian context.

One consequence of the peace process was that many of the Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad members who had been deported to Lebanon in late 1992 were allowed to return to the occupied territories in late 1993 and early 1994. They arrived prepared to use the practical knowledge that they had gained from Hizballah during their Lebanese exile.32 Hamas leaders immediately began to plan much more dramatic attacks to capitalize on these new capabilities, but they still had to tread carefully, because a majority of Palestinians at the time were supportive of the peace process. Hamas therefore needed a pretext for its attacks that would allow its leaders to claim that they were acting in self-defense in order to sell the attacks to the Palestinian people, minimize the possibility of a Fatah backlash, and justify the attacks under Islamic law.33

On February 25, 1994, Baruch Goldstein, a Jewish settler in the West Bank, opened fire with an assault rifle at Friday morning prayers in the Ibrahimi mosque near the Tomb of the Patriarchs, in Hebron. He managed to kill twenty-nine worshippers before a crowd beat him to death.34 The attack provided Hamas with the pretext it needed. After the customary forty-day period of mourning, on April 6, a young man drove his car to a bus stop in Afula, in northern Israel, and detonated the car and himself, destroying a bus and killing eight Israelis in the process. Forty-four people suffered injuries. Hamas claimed that the attack had been in retaliation for the Goldstein massacre and promised four more attacks. The following week, a second suicide bomber attacked a commuter bus, this time in Hadera, killing five Israelis and injuring thirty.35

Arafat did not know how to respond. He declined initially to condemn the first attack, lest he appear subservient to Israel and contribute to the appeal of Hamas. Two days after the bombing, the PLO issued a statement expressing its regrets over the loss of Israeli life. American leaders condemned Arafat for such a tepid response, and the Israeli opposition called for an end to peace talks. The Hamas attacks of April 1994 were therefore successful on a number of levels. They confirmed Hamas as an uncompromising advocate of Palestinian statehood, resonated with many Palestinians still horrified by the Goldstein massacre, and weakened Arafat and the peace process.

Six months later, both Hamas and PIJ resumed suicide attacks. On October 19 Hamas carried out its deadliest bombing to date, in the heart of Tel Aviv. Instead of using a car bomb, the bomber, twenty-seven-year-old Saleh Abdel Rahim al-Souwi, boarded a bus while carrying a large bag that contained twenty to forty pounds of explosives. The explosion killed twenty people in addition to al-Souwi; forty-eight others were wounded.36 Over the next ten months, four more suicide attacks credited to Hamas would kill eighteen Israelis. Three attacks credited to PIJ would result in thirty-two Israeli deaths.37

The attacks put pressure on Arafat to reign in the militants, plus he undoubtedly understood the attacks as a challenge to his authority. By mid-November, Palestinian Authority police banned street demonstrations and arrested hundreds of Hamas and PIJ members.38 The attempted repression culminated with Black Friday, November 18, when PA police fired on Islamist activists who were organizing a protest after Friday prayers at Gaza’s Filastin mosque. The gunfire turned the protest into a riot in which at least fifteen people were killed, two hundred injured, and hundreds more arrested.39 Undeterred, Hamas struck back. On January 22 two Hamas suicide bombers killed nineteen Israelis and injured more than sixty others.40

The suicide attacks, however, were unpopular with many Palestinians, who were still optimistic about the peace process. In addition, despite their actions, Hamas’ leaders also did not want to disrupt Israeli redeployments from Palestinian territory or to sabotage upcoming Palestinian elections, both of which were popular.41 Each attack usually resulted in Israel temporarily closing its borders to Palestinian workers, thus generating resentment toward Hamas. Recognizing the need to work with the PA, Hamas leaders agreed to a truce in which they promised not to carry out attacks from areas controlled by the authority. With the exception of one unsuccessful attack credited to PIJ, no suicide bombings occurred from August 1995 until February 1996.

In October 1995 Israeli agents assassinated Fathi al-Shiqaqi, one of the founders of Palestinian Islamic Jihad, in Malta.42 On January 6 of the following year, Israeli forces killed Yahya Ayyash, the Hamas bomb maker called “The Engineer,” hiding a small bomb in his cell phone and detonating it when he answered a call.43 Ayyash was Hamas’ best explosives expert and played a leading role in planning and executing the suicide attacks of 1994 as well as other Hamas missions. He was therefore immensely popular as a symbolic figure of resistance to Israel. Even Arafat paid tribute to the bomber after his death, calling him “the struggler, the martyr, Yahya Ayyash.”44 After a forty-day period of mourning, Hamas once again resumed suicide attacks against Israeli targets and in two attacks on February 25 killed twenty-five people and wounded seventy-seven.45 Two more deadly attacks, one each by Hamas and PIJ, took place in early March. These killed nineteen and twenty people, respectively, bringing the total of Israeli fatalities in the aftermath of Ayyash’s assassination to more than sixty people in little more than a week.

The resurgence of suicide attacks in 1996 has received attention because it came shortly before an Israeli general election in May and therefore undoubtedly played a role in the narrow victory of the more conservative candidate, Benjamin Netanyahu, over Rabin’s successor, Shimon Peres. Since Netanyahu and his Likud Party had pledged to reject the peace process, this chain of events suggested to some that Hamas and PIJ deliberately used their suicide bombers to influence the electoral outcome and therefore derail the peace process.46 There is certainly a superficial correlation between these events, but upon closer examination, such an interpretation raises more questions than answers. Among the most important, if the intent of the Islamists was only to disrupt the elections or to undermine the Labor Party of Shimon Peres, why were no attacks launched closer to the election date?

The attacks of February and March undoubtedly poisoned Israeli-Palestinian relations and undermined confidence in the Labor Party and the peace process, but this was true of all Palestinian suicide attacks in the 1990s. The immediate motivation for the timing of these attacks seems genuinely to have been revenge for the assassination of Ayyash. The bombings were initiated by local al-Qassam Brigades leaders, who undoubtedly sought to avenge Ayyash’s killing. A Hamas spokesman said of the attacks, “Israel assassinated Yehia Ayyash, the leader of our military wing and should be accountable for this. We retaliated by carrying out suicide missions. For us, Labour and Likud are the same. They’re two faces of the same coin.”47 That these attacks ended up having a particularly disruptive impact on the peace process as a consequence of the Likud victory was probably a welcome development from the perspective of Hamas hard-liners, but it was not the sole motivating factor.

Post-1996 there were eight more suicide attacks in the 1990s: five in 1997 and three in 1998.48 The first wave of suicide attacks ended in 1998. The election of Labor Party candidate Ehud Barak as prime minister of Israel followed in 1999, along with resumption of the peace process at the highest levels. At the time, 70 percent of Palestinians still had faith in the peace process, and fewer than 20 percent supported suicide attacks.49 More important, support for Hamas had dropped to 12 percent among Palestinians. PIJ could claim the support of only 2 percent.50 Arafat and Israeli intelligence had decimated Hamas’ al-Qassam Brigades and succeeded in cutting off much of Hamas’ funding, which consequently limited its charitable work, further eroding its support. There were no attacks in 1999 and none in 2000 until after the outbreak of the second intifada (see Chapter 6).

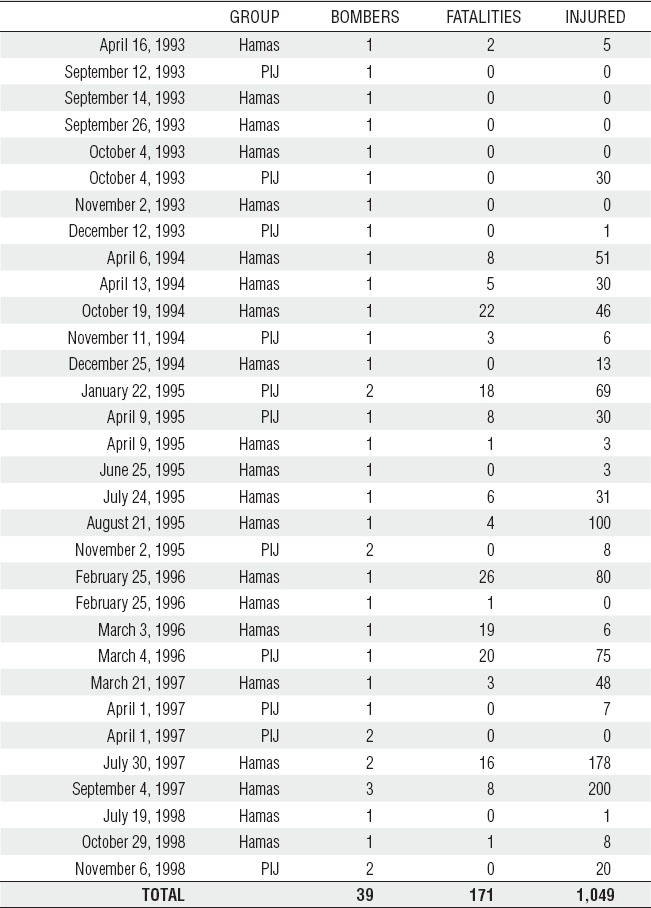

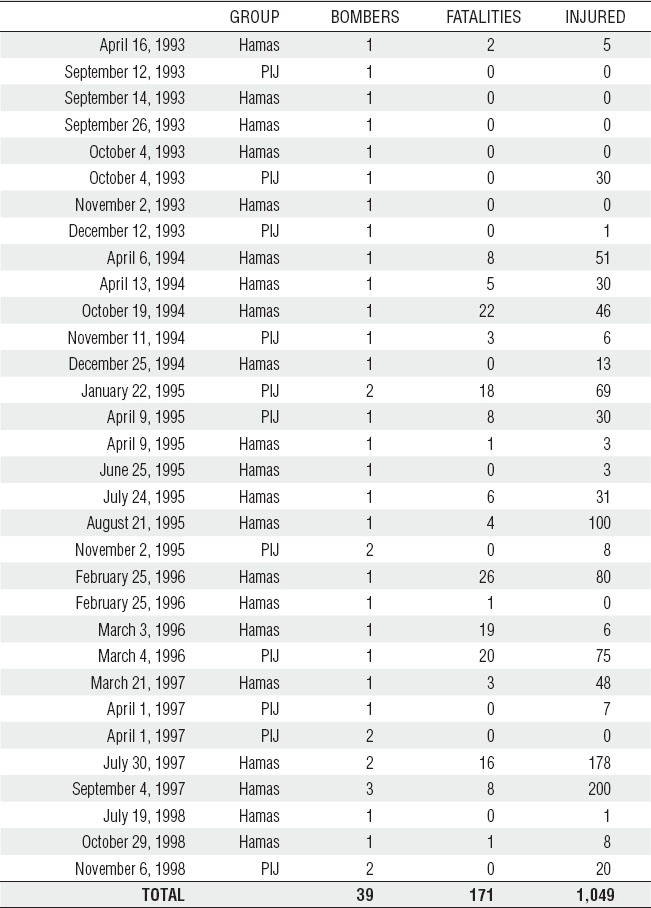

As Table 5.1 shows, after some initial, ineffective experimentation, suicide bombing quickly became the spectacular weapon that Palestinian militants sought to mobilize their communities and to inflict grievous harm on Israelis. In this instance of successful technological diffusion, to cultural compatibility one must add an additional factor, what Everett Rogers calls a change agent, which also played a significant role. A change agent is an individual or organization that helps influence the innovation decisions of others in a direction consistent with the goals of the agent.51 In the Palestinians’ case, Hizballah played the role of change agent when it hosted members of Hamas and Islamic Jihad in 1993 in southern Lebanon. Assisting Palestinian militants in their struggle against the Israeli government promised to benefit Hizballah’s own guerrilla war against Israel in southern Lebanon, so this transfer of knowledge was not particularly altruistic. Rather, it was done with the interests of Hizballah firmly in mind, making the organization a classic change agent as understood in terms of technological diffusion.

One can infer, based on changes in Palestinian suicide bombing, how the Lebanese instructors influenced their Palestinian protégés. The physical devices associated with suicide bombing seem to have been the least important. The Palestinians were already imitating Hizballah-style vehicular attacks using improvised explosives, but they clearly lacked the sophistication that characterized the bombings in Lebanon. The Palestinian militants learned by doing, however, and one can discern a steadily improving competence in their vehicular bombs from 1992 to 1994. Ayyash, in particular, embodied this culture of learning by doing, steadily improving his own capabilities and training numerous other Hamas explosives experts, until his death in 1996. On the whole, the technical elements of Hamas’ attacks show steady evolution and improvement through 1993–94 rather than a dramatic change that would point to imported knowledge.

Hizballah’s greatest gifts to the Palestinian militants were instruction in the management techniques for manufacturing the human guidance systems for its weapons and practical advice on the strategic and symbolic exploitation of suicide bombers. Specifically, Hizballah members seem to have impressed upon the Palestinians the importance of videotaped testimonies for ensuring the reliability of their recruits prior to the mission and for exploiting the media value of the attacks after the fact. Hamas began using testimonies of this nature in October 1994.52 That Hamas and PIJ had learned from Hizballah how to improve their suicide bombing added to the intimidating character of the attacks. Palestinian militants did not hesitate to exploit this connection, announcing in Gaza mosques after the bombing of October 20, 1994, that the attack was carried out using knowledge and techniques learned from Hizballah.53

TABLE 5.1 Suicide Bombings by Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), 1993–1998

Sources: Mohammed M. Hafez, Manufacturing Human Bombs: The Making of Palestinian Suicide Bombers (Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace Press, 2006), app. I, p. 79; Ami Pedahzur, Suicide Terrorism (Cambridge, U.K., and Malden, Mass.: Polity Press, 2005), 242–53; data confirmed with START Center’s Global Terrorism Database.

Apart from Hizballah’s advice on management and symbolic exploitation of suicide attacks, the emergence of a culture of martyrdom in the 1990s is the most important factor explaining why suicide bombing came to be supported by a sizeable percentage of the Palestinian community. This subculture that increasingly glorified violent death relative to life was the product of years of cultural management on the part of Islamist groups and their supporters. It took a preexisting reverence for self-sacrifice on behalf of others and turned it into something similar to the culture of death that surrounded the Tamil Tigers’ suicide bombers.

Prior to the 1990s, martyrdom was a commonly used term among Palestinians but it tended to refer to anyone who had died fighting the Israelis regardless of whether or not he or she had intended to sacrifice his or her life.54 During the 1990s, the Islamist groups deliberately sought to transform this generalized perception of martyrdom and break down the barriers between life and self-sacrifice as part of a campaign of popularizing their interpretation of Islamic values throughout the West Bank and Gaza.55 Observers during the 1990s noted the change. Imagery of militancy and self-sacrifice—in the form of television programs and graffiti and songs and rhymes taught to children—became part of the cultural backdrop.56 Like Hizballah and the Tamil Tigers, the Palestinian Islamists turned the dead into celebrities and used them to inspire their followers to behave in similar fashion. Palestinian martyrs were glorified not only in song and memory but also through rituals and holidays established entirely for this purpose.57

As a consequence, self-sacrifice became an expectation shared by militants and a growing percentage of supporters in the broader community. This culture of martyrdom was encoded and transmitted to the next generation in the forms mentioned above and also more systematically through education and schooling.58 In a poll conducted by the Islamic University in Gaza in 2001, 73 percent of children aged nine through sixteen said they hoped to become martyrs.59 The acceptance of this subculture made the task of aligning the expectations of individuals and communities with the agenda of militant groups easier for Palestinian Islamists than it had been for the IRA or PKK. As long as there was no pressing military need for suicide attacks, however, and as long as the peace process presented an alternative to violent conflict, the culture of martyrdom was restricted to a minority of Palestinians. Suicide bombing was even temporarily abandoned in the late 1990s.

The willingness to die, and to kill oneself, was a characteristic that members of the terrorist brigade of the Party of Socialist Revolutionaries in Russia used to set themselves apart from (and above, in a moral sense) their peers, not just their adversaries. Love of martyrdom similarly distinguished and elevated members of Hizballah above rival Shiite militants, for example, Amal. Membership in the Black Tigers was a mark of honor and distinction for members of the LTTE. In the occupied territories, the same process was already at work in 1991 when a section of the al-Qassam Brigades began calling itself the Martyr’s Brigade, creating a new and prestigious role for its members and presenting itself as a model for Palestinian youth to follow.60

In later years, competition among militant Palestinian groups would help fuel the escalation of suicide bombing in a process that Mia Bloom calls outbidding, meaning that militant groups escalate violence as a way to “outbid,” or outdo, one another in order to differentiate themselves in the political marketplace. Her analysis is most relevant to suicide bombing in the second intifada, but it sheds insight on the earlier phase of suicide bombing as well. Even before the dramatic escalation of suicide attacks in the 2000s, Bloom notes, disillusionment with the peace process and dissatisfaction with the corruption of the Palestinian Authority under Arafat had “provided radical groups with an opportunity to increase their share of the political market by engaging in violence.” As shown above, deadly intergroup rivalry and competition among Palestinians predates the use of suicide attackers by years.61

Some have criticized Bloom’s analysis as being inconsistent with other instances of suicide bombing, particularly the LTTE’s use of suicide attackers, which began after the LTTE had eliminated its rivals and established a near monopoly on the Tamil independence movement. This objection, however, is more the consequence of mistaking cause and effect during the process of militant escalation than it is a valid critique of the phenomenon. Escalation of violence does not cause suicide bombing; rather, some groups choose to escalate violence as a way to establish their own identities, internally and externally. Violence is therefore the effect, while affirmation of group identity is the ultimate cause. As perhaps the most extreme form of group-mediated violence, suicide bombing affords the most militant groups the opportunity to affirm (or to confirm) their radical identities. Groups that have already differentiated themselves through competition and outbidding are more likely to be able to use suicide bombing because it is compatible with established organizational norms. It follows that the cultures of martyrdom examined to this point were not established with the specific long-term goal of making suicide bombing possible, but instead were established to create group identities, bind members together, and collectively to make their radicalism and enthusiasm available to their leaders for organizational use. Suicide bombing is but one such use made possible by these cultural antecedents.

Understanding the importance of radicalism and competition for identity formation also offers a plausible explanation for why suicide bombing has tended to be taken up by relatively young groups.62 New groups, spun off from previously existing organizations, must create new identities for themselves in the political marketplace of their communities and a new internal culture to provide group coherence and camaraderie. Extremism can be an effective way to do this. Hizballah differentiated itself from Amal through its dedication to an uncompromising vision of Islam characterized by reverence for individual self-sacrifice. The LTTE, originally one new group among many, also distinguished itself through its extremism, and in time its extremism would make Prabhakaran’s use of suicide bombers possible. For Hamas and Islamic Jihad, suicide bombers became symbols representing the convictions and values of their members. The bombers then played a significant role in establishing the political identities of Hamas and Islamic Jihad, differentiating the two groups from Fatah, and served as one means by which the two sought to compete with one another for a share of the Palestinian political marketplace.

Palestinian militants decided to use suicide bombing on a regular basis in late 1993 to undermine the peace process and differentiate themselves from their rivals. They developed the capability to use suicide attackers through a process of trial and error, in which members of Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad integrated their practical knowledge with the managerial techniques already developed by Hizballah. Suicide bombing became sustainable when a significant percentage of Palestinian society came to accept it as a legitimate means of resistance and political mobilization.

Palestinian suicide bombing did not simply spring into existence as a well-organized activity. Instead, leaders deliberately shifted cultural and organizational parameters to facilitate the emergence of a culture of martyrdom, which in turn facilitated the introduction of suicide bombing. Palestinian suicide bombing then was a mix of indigenous know-how, generated through trial and error, and imported knowledge facilitated by a willing and experienced change agent. It was a hybrid that resembled Hizballah’s suicide bombing in some respects and in others demonstrated considerable originality (for example, in the use small, human-portable bombs).

One characteristic of this first wave of suicide attacks is worth noting. During the 1990s, as Hamas and Islamic Jihad bomb makers developed their technical competency, the nature of suicide missions began to change. The first attacks were with vehicle-born weapons, but by late 1994 suicide attackers had begun to resort to human-borne weapons, such as belts. This shift to smaller, simpler bomb designs helped make suicide bombing even more transmissible, potentially allowing smaller groups with fewer material resources and logistical capabilities to carry out suicide attacks. This trend, accompanied by an intensifying culture of martyrdom and, after 2000, a more pressing military need, facilitated the use of suicide bombing by small, relatively autonomous local groups and set the stage for the dramatic escalation of Palestinian suicide bombing in the new millennium.