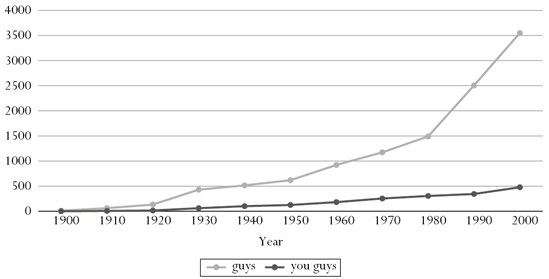

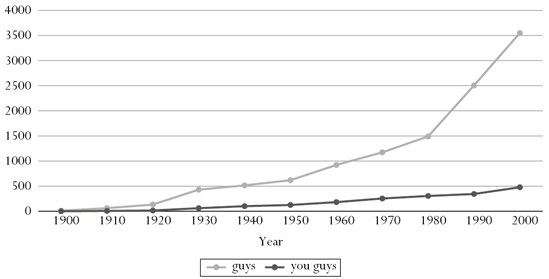

FIGURE 10.1 Frequency of “guys” and “you guys”

Source: Corpus of Historical American English, Brigham Young University

By mid-20th century, “guy” and “guys,” having made the transformation from Guy Fawkes to effigies of him and then to designating the lowest of male humans, gradually had expanded its domain to include not just lower-class or funny-looking or socially inept males but finally all males and all classes, with mild implications of camaraderie. Nobody planned or intended this expansion; it was just a natural development of a convenient word to its full extent. It helped that, being a slang word (or at least informal), it developed without being noticed by makers of dictionaries or grammar books, who might well have found fault with it. So “guy” today remains a widely used designation for anyone male, from infant to elder, from richer to poorer, from saintly to wicked, from any place or religion on the globe. Every male is a guy, and that’s nice.

But the plural “guys” didn’t stop even there. By the middle of the 20th century, it had expanded once more, to include women along with men in its embrace, indeed the whole human race. And that, in turn, made “guys” or “you guys” suddenly the leading candidate for the centuries-long vacancy in second-person plural pronouns advertised in Chapter 8.

Thanks to the Brigham Young University (BYU) database, Corpus of Historical American English (CHAE), we can trace the accelerating growth of “guys” and “you guys” in our language to the present day. In the CHAE sample of more than 400 million words, from 1810 to 2010, the CHAE found 1776 instances of “you guys,” all of them dated 1910 or later. If there were earlier examples, CHAE didn’t find them, perhaps because “you guys” was so informal or slangy that it would rarely appear in print. Where it did, it was mostly in dialogue in fiction or lines in a play. By the time the database was able to catch examples of it, “you guys” had begun to move toward respectability.

Specifically, decade by decade of the past century, CHAE finds in its database these numbers of “guys” and “you guys” (see Figure 10.1).

FIGURE 10.1 Frequency of “guys” and “you guys”

Source: Corpus of Historical American English, Brigham Young University

For the 21st century, BYU’s Corpus of Contemporary American English, with more than 560 million words just for the years 1990–2017 (about 10 times as many words as CHAE for each decade), found 3748 examples from the 1990s, 5005 examples from the 2000s, and 6656 from the shorter period 2010 to 2017.

And in the 14 billion words of BYU’s new iWeb Corpus, “you guys” appears 351,905 times, or about once every 40,000 words. “You guys,” along with plain “guys,” is at home in present-day American English, encompassing not just males and females but everyone else considered human, including GLBTQs.

It’s easy to understand why this expansion happened. “Guy,” from the beginning and through all expanded uses, remained solidly male, a characteristic of the word going back to its original, the definitely male Guy Fawkes. But “guys” was different. It was used in the 19th century to refer to groups. These were groups of males at first. But in many such groups, occasionally a female would be included.

Here’s a 1911 example, from Dawn O’Hara, The Girl Who Laughed, the first novel by Edna Ferber, who later won a Pulitzer Prize for her novel So Big. It’s only one instance, and the author doesn’t call attention to it. If she had made a fuss about it, that might have elicited criticism. But she didn’t, and in fact it appears that she didn’t notice anything special about it. It slipped under the radar without comment.

The narrator of the story is Dawn herself, telling of her experience working in New York City as a journalist, a mostly male occupation at that time. Her colleagues on the newspaper are all men. In a hospital one of them, Blackie, is dying after an automobile accident. Dawn is the one woman among five colleagues summoned to the hospital for a quick farewell. Blackie says “you guys” to this audience of one woman and four men:

I met them in the stiff little waiting room of the hospital—Norberg, Deming, Schmidt, Holt—men who had known him from the time when they had yelled, “Heh, boy!” at him when they wanted their pencils sharpened. . . .

A nurse in stripes and cap appeared in the doorway. She looked keenly at the little figure in the bed. Then she turned to us. “You must go now,” she said. “You were just to see him for a minute or two, you know.” Blackie summoned the wan ghost of a smile to his lips. “Guess you guys ain’t got th’ stimulatin’ effect that a bunch of live wires ought to have.” . . .

They said good-by, awkwardly enough. Not one of them that did not owe him an unpayable debt.

From 1911, also, we find a play by Rachel Crothers titled “He and She” that has “guys” entirely female, in the phrase “wise guys”:

millicent. Oh, mother, don’t be cross. (Reaching a hand up to her mother’s arm.) Sit down and talk a minute.

herford. It’s late. You must—

millicent. That’s nothing. We girls often talk till twelve.

herford. Till twelve? Do the teachers know it?

millicent. (Laughing again.) Oh, mother, you’re lovely! Do the teachers know it? Why, don’t you suppose they know that they don’t know everything that’s going on? They’re pretty wise guys those ladies—they know when to let you alone. That’s why the school’s so popular.

“Guys” also can apply when the “group” consists of just two, one man and one woman. It’s in the dialogue for a 1930 movie by Earl Baldwin and Ruth Rankin, The Widow from Chicago:

(The two gunmen stare sheepishly at each other. Crestfallen, they slowly put away their guns. Mullins and Polly dance into the scene. Both he and Polly are grinning.)

mullins. (lightly) Don’t get excited, boys. It’s all in fun.

first gunman. (huffed) Yeah? You guys got a swell sense of humor. (Mullins and Polly laugh.)

Sinclair Lewis provides another example of inclusive “you guys” in his 1938 novel Prodigal Parents. Sara, the 28-year-old daughter of a car dealer in upstate New York and a graduate of Vassar, is attracted to Gene, a radical revolutionary, who says to her, “Nobody comes through with funds for the revolution like the wives of millionaires, even after we’ve openly announced we intend to overthrow the Democratic State and institute a real, honest-to-God dictatorship of the rednecks like me. How come? You’re a capitalist, darling. Why do you guys in the ruling class let us get away with it?”

In 1945, writer Elma Lobaugh used “you guys” for a male–female couple in her mystery novel, She Never Reached the Top. Jennie, who arrives with Jim, is the narrator:

Jim honked the horn and a minute or two later light streamed out of the garage doors to the right of the house. And when I heard Bernard’s loud voice I had to laugh at the thought of the ghost of a fragile girl haunting any house where he lived. “Thought you guys were never going to get here. How’re you, Jennie? That blonde you liked couldn’t come this week end, Jim. Here, let me take those bags.”

As the 20th century progressed, the use of “guys” to mean everyone was becoming more and more pervasive. Nobody was advocating it; it just seemed the normal and usually positive way to refer to a group of at least two humans. Rita Salz, a resident of Princeton, New Jersey, and formerly of Connecticut and West Virginia, in a November 2018 message attested to the female use of “guys” and “you guys” as far back as the mid-20th century:

My undergraduate years began in Autumn 1956, at Smith College. Those were the days before transgender (except for someone named Christine Jorgensen), so we students were female females. And “you guys” was the common phrase for addressing a group of fellow students.

In fact, I recall one event in which the use of the phrase was called into question. The occasion was the wedding of a Smith friend a class or two ahead of me. It was a kind of wedding I’d only read about, held at the Greenwich, Connecticut home of the bride’s parents with the wedding party in formal wear (which did not stop the groomsmen from shoving one another, fully-clad, into the classic pool, after the ceremony). The bridesmaids and many, perhaps most, of the bride’s friends were Smithies. One of the groomsmen overheard a “Hey, you guys,” from a late-arriving Smithie, and took her to task for using the phrase in addressing a gaggle of girls.

He was ignored. But I assure you, “you guys” was common parlance among us at Smith, in the late 1950’s.

Another recent correspondent wrote,

“Guy” may be gendered, but “you guys” certainly denoted a group without reference to gender when I was growing up in New York State and Pennsylvania. Have heard it for decades used in groups of girls or women, calling to other girls/women.

In response to a post by Erin McKean on the Language Log website in 2010, “Julie” wrote:

As another Californian, I agree [that “you guys” is not new in California.] I’ve said it for about 50 years, and my mother (nearly 80) uses it unconsciously, just as I do. It’s a set phrase, and applies to groups of both sexes. (For the record, I doubt I have ever said “you boys,” or “you girls” for any reason. Those, to me, sound demeaning if not referring to children.)

By the later 20th century inclusive “you guys” was absolutely routine. In The Fan Club (1974) by Irving Wallace, for example, set in Los Angeles, a 9-year-old daughter addresses her parents as “you guys.” The father narrates:

the children will be in from playing soon, hungry and dirty. Like our marriage, I think, hungry and dirty. While I ate the Grape Nuts, Natasha and Sean came in, brown arms and legs and blond hair crowding through the door at once, the screen slamming behind them. Natasha is nine; she is the love child who bound us. Sean is seven. Looking at them I felt love for the first time that day.

“You slept late,” Sean said.

“That’s because you were up late, you guys were fighting,” Natasha said. “I heard you.”

Around the English-speaking world, “you guys” continues to grow. That’s the case in England, home of the original Guy, and as far away as Australia. Canadian linguist Sali Tagliamonte noted in March 2018 about the English city of York, the home town of Guy Fawkes:

I have just returned from a field trip to York England with a team of 7 students. We spent the week doing sociolinguistic interviews—47 in all! Now we will be conducting a 4 x 4 comparison of intensifiers in York (1997) and York (2018) compared to Toronto (2003) and Toronto (2018). The idea is to “Catch Language Change.”

One thing I noticed that was quite striking. When I moved to York in 1997 the use of “you guys” for 2nd person plural was unheard of in York. When I used it with my classes of young men and women they would pretty much fall on the floor laughing. This trip, I heard so many people using “you guys.” It has taken over!

Nowadays, despite its masculine origin, “guys” or its equivalent “you guys” is heard increasingly worldwide where English is spoken, and in particular in the United States, as a second-person plural pronoun referring to any group of two or more. In fact, it is so frequent and so normal, most of the time we don’t notice that we are saying it. We can tell it has become the norm because we almost always use it without thinking.

Well, with a few exceptions, as the next chapter acknowledges.