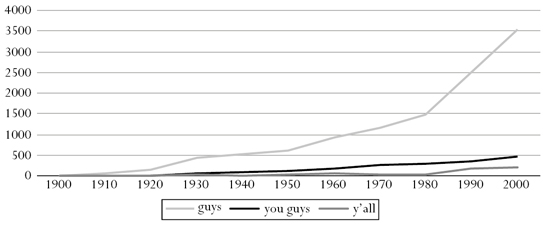

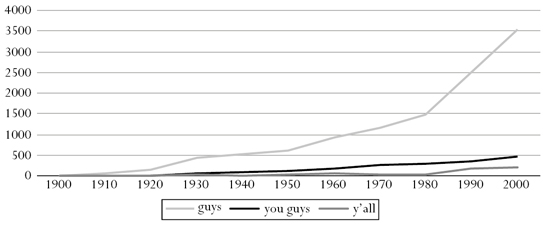

FIGURE 11.1 Frequency of “y’all,” “guys,” and “you guys”

Source: Corpus of Historical American English, Brigham Young University

Feminist and Southern objections

Little attention has been paid to the pervasive spread of “guy” and “you guys” in recent times, even though in the 21st century it has defeated its rivals to take its prominent place among the personal pronouns of English. For the success of “guys” in this context, the lack of notice is a good thing, perhaps equivalent to the lack of attention to the activities of the Gunpowder Treasoners that allowed their plot to come so close to fruition.

Throughout the centuries, there seems to have been no noticeable objection to the word “guy” itself, even though it originally referred to the demonic and terrifying villain Guy Fawkes, and then gradually came to refer to men of the lowest class. As it spread, in America in particular, it shed awareness of its despicable early referents, allowing it to put on the mantle of informal conversation. In that way it was like America’s greatest word, OK, which became respectable and indispensable only after its origin as a dimwitted deliberate misspelling of the initials of “all correct” was forgotten.

So “guy” and “guys” were a success before they faced criticism. But face it they finally did, and the opposition hasn’t ceased.

The first stern objection came in the latter 20th century, from feminists who noticed the inherent sexism of the English language. It was so inherent, so normal, that rarely, if ever, had it been brought to everyone’s intention that using “man” to designate both males and females meant implicit subordination of females, who were invisible in statements intended to include them, like “all men are created equal.” That also implicated words beginning or ending with “-man,” like “mankind,” “fireman,” “policeman,” and “chairman.”

Calling attention to this gender bias has resulted in efforts to make our language truly gender neutral, by deleting sexist vocabulary and replacing it as needed. That works well when a familiar synonym is available. We are used to saying “firefighter,” “police officer,” “chair.” It’s harder when the synonym isn’t so readily available, as, for example, in the case of “freshman.” It contains the unquestionably sexist “man” but with the emphasis on the first syllable, the gender-neutral “fresh” that would be lost if the word were replaced by “first-year student.” That replacement therefore is not always made, even by some who generally favor gender neutrality.

Along came “guy” and “guys,” then, always strongly associated with males. And, for some even in the present day, occasionally with lower-class or uncultivated males. While, under feminist pressure, other masculine words were receding in actual usage, “guy” and “guys” were merrily rolling along with little interference. “Guys” was calmly reaching out to swallow humanity whole, while “guy” provided a sharp contrast, remaining decidedly male.

It’s one of the “pet peeves” that lexicographer Erin McKean wrote about for the Boston Globe in 2010. There’s “a perceived gender disconnect,” she observed, offering this example: “The waiter wouldn’t address a group of men and women with ‘you gals,’ so why should he or she use ‘you guys’? This may shortly be followed by another kind of indignation: ‘Do I look like a guy?’ ” Or, she adds, “ ‘You guys’ may simply make some women feel overlooked or ignored, especially a single woman in a group being addressed as ‘you guys.’ ”

When it was reprinted in the Linguist List blog later that year, McKean’s column elicited more than 100 responses. Among them:

I would guess that the waitress who said “you guys” to older people was probably young and to her the phrase was normal for addressing a group informally, while the listener who thought it was demeaning was probably at least middle-aged. Conversely, to me, “you folks” in that situation would have sounded condescending on the part of the young waitress, “talking down” to the older folks by using their own idiom! (marie-lucie)

for everyone that says “you guys” is gender neutral, how come all these articles out there have headings like “How to make GUYS want you,” “What GUYS mean when they say. . . .”

You CANNOT have the same word that you are clearly using for males to be gender inclusive unless you accept the fact that it’s the same as using MEN for a group of people of either gender or female only.

Don’t tell me people who use “You Guys” don’t know what they are saying, as I hear many people dropping the YOU and just saying GUYS! to get people’s attention . . . and guess what . . . people who actually THINK and give a damn about language and are not brainwashed to thinking something black is really white, they have every right to comment and ignore people who use this type of logic. BTW for those who can’t think of anything other than “You Guys” try “You All,” “Everyone” “You 2, 3, 4 (whatever number of people you are referring to,” “You Folks,” “Friends,” “We” . . . and many more. . . . Try using your brain and not being so lazy!

If only language were logical, this argument would be hard to refute. It’s difficult to make a logical case against her reasoning that a word can’t be masculine in the singular and gender neutral in the plural. But language doesn’t work that way. It’s conventional, not logical. Nowadays we hear “guy” a lot referring to any male, and “guys” a lot referring to every human. Convention trumps logic. So if we want to avoid saying “guys” to a group of women, it’s as difficult as it is to keep to a strict diet when everyone else is eating cake.

And just as logically, you could look at it another way, as a triumph for feminists. You could argue that “guys” shows women conquering territory that had been exclusively male. It’s like women gaining full membership in a previously all-male club. Who is the conqueror? Or is it a matter of conquest at all?

Nowadays, in any case, despite its masculine origin, “you guys” or its equivalent “guys” is heard in English worldwide as a second-person plural pronoun. For most of the English-speaking world, and certainly for North America, it has become the conventional way for one person to call for the attention of others regardless of gender. We can tell it has become the norm because we almost always use it without thinking.

Y’all

Another alternative to “guys” or “you guys” is the well-known “y’all.” It’s the norm in the Old South, encompassing Virginia in the east to Texas in the west, and Tennessee, Arkansas, and Oklahoma to the north. The South lost the Civil war, but not “y’all.” If anything, “y’all” now seems stronger than ever, perhaps the single most prominent feature of southern speech.

When you hear “y’all,” you know you’re in the South, or else visiting with a southerner in some northern place. “Y’all” has the advantage over “you guys” of seeming both friendly and polite, and of not being considered slang. “Guys” can now enter through the front door rather than having to beg at the back, but only “y’all” is welcome even in the parlor.

Evidence of “y’all” goes back half a century before evidence of “you guys” in the Oxford English Dictionary. The OED cites a humorous story in the Southern Literary Messenger in 1859 by “Mozis Addums” (George William Bagby), writing about his life in a boarding house in Washington, DC:

Packin uv pork in a meet house, which you should be keerful it don’t git hot at the bone, and prizin uv tobakker, which y’all’s Winstun nose how to do it, givs you a parshil idee, but only parshis.

The first three of 574 “y’all”s in the Corpus of Historical American English (CHAE) are in a single passage also by Bagby, where a Virginian imagines how he would spend $50 million benevolently in his home state. Here he reflects on the many men he has known:

“Did y’all know Woody Latham?” said I. And they answered and said they did.

“We desire some pizen,” they added.

“Did y’all know Judge Semple?” said I. They answered yes, and most of them lied. “And did y’all know Jim McDonald and Bob Ridgway and Chas. Irving and Marcellus Anderson and Philander McCorkle.”

More evidence comes in Edward Eggleston’s Queer Stories for Boys and Girls (1884):

Then he drew the revolver, carefully examined the chambers to see that all were filled; motioned with his hand to those on the ground, saying, quietly, “Pick those up. Y’all may need every one of ‘em.” The Blue Grass dialect seemed cropping out the stronger for his preoccupation.

Finally, in 1886 S. Pardee wrote for Dixie¸ published in Atlanta, about “Odd Southernisms: A Few Examples of Quaint Sayings in South Carolina”:

“You all,” or, as it should be abbreviated, “y’all,” is one of the most ridiculous of all the Southernisms I can call to mind.

These are the database numbers from CHAE for “y’all,” decade by decade (see Figure 11.1).

FIGURE 11.1 Frequency of “y’all,” “guys,” and “you guys”

Source: Corpus of Historical American English, Brigham Young University

For some time, “y’all” has been assaulted by “you guys” aiming to replace it as the go-to second-person plural pronoun in the South. The South may have lost the Civil War, but to this day it seems to hold off the northern “you guys.” Is the Solid South still really holding firm at the Mason-Dixon line, or is “you guys” infiltrating and spreading like kudzu, as it is elsewhere?

Some claim that it is. In the Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE), the usage note for “you guys” says “orig. chiefly North; now widespread; esp freq. among younger speakers.” It backs this up with two citations that suggest the invasion has been on its way at least since the recent turn of the century:

2000 American Speech 75.417: Meanwhile, just as y’all seems to be spreading outside the South, you-guys is moving into the South, especially among younger speakers. [Quoting a 1999 survey by Natalie Maynor, which continues: “In a survey of university students in Mississippi, Alabama, North Carolina, and South Carolina, I found a surprisingly large number of respondents who said that they might use you-guys.”]

And DARE quotes a 2002 article in Alcalde from central Texas:

From this office . . . you can hear it in the classrooms, at the shuttle bus stops. “You guys know where this stops?” You can hear it in the bookstores and restaurants that encircle campus. “You guys know what you want to order yet?” I’m speaking, of course, about the impending death of the expression “y’all” at the hands of the address “you guys,” like an aggressive exotic species supplanting a native one.

Nevertheless, at the end of the second decade of the 21st century, the South seems to be holding on to “y’all.” In July 2018, wondering about the current situation, I invited readers of the Lingua Franca blog of the Chronicle of Higher Education to report from the field. The responses suggested little change from the situation in 2000. This is a typical response:

Here in southeast Missouri I have to say I think it has become a standoff, as some generations are standing strong with “y’all” and “all y’all”, I do have to say I am hearing more and more younger generations using “you guys.”

I’m from the upper South—Fayetteville, Ark.—and still hear “y’all” considerably more frequently than “you guys,” which I started hearing in Fayetteville as early as the mid-1970s. It very likely came via friends with parents who arrived here from points north to teach at the University of Arkansas, so the kudzu has deep roots.

But people who do use “you guys” here almost blush after saying it for some sense that it sounds uncouth or gendered, very often apologizing and clarifying they meant “all of you” or “you all,” without the contraction.

Recently, I thought perhaps “y’all” was on the rise after I attended the state mathematics quiz bowl—further south in the state—and heard the organizer congratulating the attendees for their participation: “All y’all give all y’allselves a round of applause.” (Charlie Alison)

And from the Sunshine State:

I’m from Florida, where we joke that the further south you go, the further north you are. Among the transplants and snowbirds, “you guys” is definitely more common, unless they’re trying to be ironic. From true Floridians, however, I still hear “ya’ll” used frequently, even among students.

I also feel like I heard “you guys” more in the 90s than I do now, although that could be the result of having been on a college campus with a diverse national and international student body. I’m now at a small college that serves a more local population. Personally, I use “ya’ll” in conversation, but have always felt weird typing/writing it, and in those instances tend to use “you.”

Southern Alabama here. Y’all is still the dominant form but I do hear you guys from younger folks and transplants occasionally (usually transplants do a pretty good job of picking up y’all). I especially hear it from servers in restaurants, maybe because they feel it’s more formal somehow? It drives me crazy because not only does it not feel formal to me, it doesn’t even feel friendly like y’all does.

But, I also hear y’all being used more and more from northerners too, and not just AAVE [African American Vernacular English] speakers but folks from predominantly white areas like Vermont. It will be interesting to see how it turns out in 50 years or so.

But I’ll leave the last word to the preeminent scholar of Southern American English, Michael Montgomery of the University of South Carolina, writing recently:

Yes, you guys has been making steady inroads in the South over the past 30–40 years (the period of my observation). When growing up, I recall that even the noun guy ‘fellow’ had a slightly crude tinge of disrespect for any male to whom it was applied. As an East Tennessean with Deep South parents, all I ever heard was y’all (and occasionally you all). These two pronouns (along with various periphrastic forms such as you two or you fellows) represented default usage. You guys was unknown as a pronoun, and to include females it was inconceivable.

I can vividly remember sitting close to a lad of 10–12 and his parents at an airport gate maybe 30 years ago and being shocked to hear him address his parents as you guys. I also recall going to a restaurant with my aunt and uncle c1995 and my uncle’s visible excruciation when the young server miss queried “what can I get you guys tonight?” At the very least, the pronoun communicated a chumminess that I regarded as entirely inappropriate.

And he adds:

I’m not nearly as sanguine about the resistance to you guys as I once was. I still hear double modals nearly every week with the same pragmatics as ever, and speakers seem oblivious to using them.1

But I hear you guys as well, though I don’t like it! And I’m sure that tens of millions of Americans who grew up with y’all now have switched.

1. Montgomery explains double modals:

[In 2018] a physical therapist said to me, “Since it’s not five o’clock yet, I might can get hold of them before they close,” whereupon I asked the young fellow about his roots. He responded “Charleston, South Carolina.” In other words, he expressed possibility without claiming to speak for someone not already consulted and about whom he was unsure. He was hedging, not making a promise he might couldn’t fulfill himself.