Side by side with conventional methods of warfare practiced openly in the battlefield—whether on the ground, in the air, or on the sea—there were probably always other forms of fighting taking place; leaders were being poisoned, secret agents were dying in questionable car accidents, and developers of new weapons were mysteriously disappearing. While such covert forms of warfare are the mainstay of a whole genre of action movies, by and large, they have escaped the radar of philosophical and legal attention. Things have changed in the past decade from the time such “irregular” killing, now known as targeted killing (hereafter “TK”), became an official tactic in some democratic states, notably Israel and the United States. The question of whether or not such killing is legitimate and towards whom (military activists only or political/religious leaders too) has been extensively discussed over the past decade and is still deeply controversial. Though most of the discussion has been conducted from a legal point of view, for most writers there seems to be no discrepancy between the legal and the moral points of view. Most writers who believe that TK is legally unacceptable also believe that it is morally unacceptable, while those who believe that TK is legally justified tend to think that it is also morally alright. Furthermore, it is often moral arguments that tend to ground the legal conclusions.

In this chapter, however, I say nothing about the legal status of TK, but instead focus on its morality. In section II, against most common wisdom in the field, I suggest that the notion of TK should be released from its association with the war (or wars) against terror. In section III, I present three interpretations of just war theory that will serve as the basis for my moral analysis of TK. In section IV, I turn to this analysis and show how each of the three interpretations supports the practice of TK.

I shall take the intentional and indiscriminate killing of civilians to be the salient characteristic of terror. Paradigmatic examples would be the blowing up of a restaurant or of a school bus, or the shooting into a crowd in a shopping mall. Since both Al Qaeda and Hamas are terrorist organizations under this definition, and since many of their members have fallen prey to operations of TK carried out by the United States and Israel respectively, it should come as no surprise to find that most of the literature takes it for granted that the normative status of TK depends on it being a counterterrorism tactic. Blum and Heymann, for instance, start their recent discussion of TK by asking the reader to imagine the following scenario:

[T]he US intelligence services obtain reliable information that a known individual is plotting a terrorist attack against the United States. The individual is outside the US, in a country where law and order are weak and unreliable. US officials can request that country to arrest the individual, but they fear that by the time the individual is located, arrested, and extradited, the terror plot would be too advanced, or would already have taken place.1

Given such circumstances, they ask whether the United States would be allowed to target this suspected terrorist without first capturing, arresting and trying him, and their subsequent discussion is aimed at answering this question. Thus, their entire discussion is conducted under the assumption that TK is a “counterterrorism tactic.”

Similarly, in his chapter in this volume, Jeremy Waldron starts his discussion of TK by asking whether we would be comfortable with some norm, N1, concerning TK, being in the hands of our enemies. This is what N1 says: “Named civilians may be targeted with deadly force if either (a) they are guilty of past terrorist atrocities or (b) they are involved in planning terrorist atrocities (or are likely to be involved in carrying them out) in the future.”2 Finally, note the title of an influential article by David Kretzmer that poses the central dilemma in the field: “Targeted Killing of Suspected Terrorists: Extra-Judicial Execution or Legitimate Means of Defense?”3 This association between TK and counterterrorism is ubiquitous in the moral and legal literature on TK.4

To see why the association is misleading, let us slightly change the scenario portrayed by Blum and Heymann. Instead of the potential target plotting a terrorist attack—that is, an indiscriminate attack against civilians—imagine that he is plotting a military attack on some American military facility, in the United States or abroad. Imagine that he plans to launch a very accurate, GPS guided missile against this facility. The other parts of the story remain the same, especially the inability of the United States to rely on law enforcement agents to take care of the threat by arresting this individual. Let’s call the original scenario The Terror Scenario (T-Scenario) and the revised one The Military Scenario (M-Scenario). (I realize that nations like the US and Israel often describe any attack against them by non-state groups as a terror attack, regardless of whether the target is military or civilian. However, while their wish to delegitimize their attackers is understandable, calling attacks on military targets “terrorist attacks” is conceptually and normatively misleading.)

Should our judgment regarding the use of TK in the M-Scenario be different than our judgment regarding its use in the T-Scenario? I think not. The moral justification for killing the individual in Blum and Heymann’s story—if such a justification exists—must lie in the right to self-defense, and for this right to be activated, a number of conditions must be satisfied: that the plotted attack is unjust; that the only way to stop it is to kill the would-be perpetrator; that such killing is proportionate to the intended evil; and, in the view of some philosophers, that the plotter is morally responsible for the threat posed. Since, ex hypothesi, these conditions are satisfied in both scenarios, killing the would-be perpetrator would be permissible in both, which means that the terrorist aspect of the intended attack makes no difference regarding the permissibility of TK.

In response, one might argue that since, by its very nature, the threat in the T-Scenario is much graver than the threat in the M-Scenario, TK would be allowed only in the former but not in the latter. But this response is misguided. First, the fact that an attack is terrorist in the sense used here does not necessarily mean that it is more serious than a non-terrorist attack. The potential harm of terror attacks to human lives and to national security, just like that of military attacks, is a matter of degree. Some terror attacks harm only a few individuals and have only a marginal effect on national security, while some military attacks harm the lives of many and pose a very serious threat to national security. Hence, there is no reason to suppose a priori that TK would be permitted only against the perpetrators of terror attacks and not against those who attack military targets. Second, even if indiscriminate attacks on civilians were in some sense worse than discriminate attacks on military targets, the latter might still be severe enough to ground a right to self-defense of the potential victims, or of the state acting on their behalf, including the right to use TK if necessary. And, of course, the entire just war tradition is based on the idea that the threat posed to states by attacks on their military facilities and personnel substantiates a right to use lethal force against the attackers. Surely not only full-fledged wars justify such a response, but more limited attacks on military targets as well.5

In the past decade, we have become all too accustomed to real-world examples of the T-Scenario. Consequently, we have come to associate TK with counterterrorism, both conceptually, that is, characterizing TK as directed against terrorists, and normatively, that is, regarding its counterterrorist nature as the basis for its moral and legal justification. But one could easily think of examples of M-Scenario too, namely, guerilla organizations that cause serious harm to military facilities and personnel while refraining, as a matter of principle, from attacking civilians. Their members do not wear uniform, they hide among the civilian population, and there is no reliable government to which to turn in order to ask for them to be arrested. If TK is justified against terrorist organizations, it is unclear why it would be unjustified against such guerilla organizations too.6

To make the point more concrete, think of the following possibility. Assume that Hamas gets hold of more accurate missiles than those it currently has, and that it decides to fire them only at military targets. This possibility is not altogether imaginary because, in response to the Goldstone Report, Hamas insisted that it had never aimed at civilian targets.7 This claim is evidently a sham, but nevertheless it might reflect the beginning of an understanding on the part of Hamas that because of the widespread disgust evoked by terror, targeting military objectives might turn out to be more beneficial to their cause than targeting civilians. If Hamas adopts such a new tactic and all else remains more or less equal, Israel might still be permitted to use TK against Hamas activists. The same goes for Al Qaeda. Imagine that instead of the World Trade Center, the 9/11 attackers had targeted only military objects: The Pentagon, West Point, The Naval Academy, etc—all of them legitimate targets in war. Would the American response have been less severe? More to the point, would the United States then have been morally prohibited from using TK against bin Laden and his comrades?

It is my contention that terror organizations, such as Hamas or Al Qaeda, manifest all the typical features of guerilla organizations, namely, the conduct of an irregular war against a perceived occupying or colonial entity, the practice of taking shelter within the civilian population, and so on, though their targets are, for the most part, civilian rather than military. The point of this section was to argue that if TK can be justified against organizations like Al Qaeda and Hamas, it is by virtue of the guerilla component of these organizations, not by virtue of the terror component. If TK is justified, it is because the members of such organizations do not fight in the open—in the battlefield—as in regular (“old”) wars, but act out of hidden shelters, in a way that often makes TK, especially by drones, the only way to fight against them. The arguments that support TK would be just as convincing, or, at any rate, convincing enough, if these organizations decided to shift their fire from civilian to military targets, if their attacks became discriminate instead of inhumanely indiscriminate.

Much of the literature on TK concerns the dilemma of whether TK should be analyzed in terms of the rules concerning law enforcement, or in terms of the rules regulating warfare (jus in bello).8 This is indeed a crucial dilemma in this area. However, the impression one gets from some of the literature is that whether or not a situation is defined as war is a bit arbitrary, a matter of formalistic legal definitions whose moral logic is not always clear. What I propose to do in this section is to examine the legitimacy of TK according to three competing interpretations of just war theory (JWT). I hope to show that this examination yields interesting results regarding the legitimacy and scope of TK, as well as regarding the normative definition of war. By examining the way each of these interpretations of JWT would treat TK, I hope to contribute not only to a better understanding of the normative status of TK, but also to a better understanding of JWT itself. (In light of this discussion, the dilemma between the law enforcement model and the war model will turn out to be secondary.)

What is shared by all proponents of JWT is the conviction that wars are not necessarily immoral, and that the conditions for the morality of war are such that they can be and are at times satisfied by the warring parties. But, beyond this shared conviction, there is substantial disagreement about its theoretical basis. In contemporary discussions of JWT, three main models can be identified: the Individualist model (“Individualism”), the Collectivist model (“Collectivism”), and the Contractualist model (“Contractualism”). I present each of them in turn and then try to see what follows with regard to TK.

One further comment before we present these three models. Since TK is a tactic of warfare, its moral status belongs to the domain of jus in bello. While traditional JWT, just as international war, regards this domain as independent of questions regarding jus ad bellum, this view has been seriously challenged recently, mainly by Jeff McMahan. I suggest we bypass this issue by assuming, for the sake of argument, that in terms of jus ad bellum, the countries using TK are justified in their initial decision to go to war, or to use lethal force, as they are responding to unjust threats against them. Everybody agrees that the justness of a cause does not legitimize all means, hence the question we wish to answer: is TK a legitimate means of warfare given that the war of which it is a part is just? Let’s see what the various understandings of JWT might offer as answers.

According to Individualism, the permission to kill human beings in war is ultimately the same license we have to kill in individual self-defense. The conditions that must be satisfied for some individual, V, to be permitted to kill another individual, A, in self-defense, are the same conditions that would allow V1 + V2 + V3 to kill A1 + A2 + A3 in self-defense, and the same conditions that would license the use of lethal force by an entire army against another army. In the words of McMahan, the prominent advocate of this model, “the morality of defense in war is continuous with the morality of individual self-defense. Indeed, justified warfare just is the collective of individual rights of self- and other-defense in a coordinated manner against a common threat.”9 Individualism might concede that the threats that typically trigger a right to wage war (the threat to territorial integrity or to sovereignty) are almost necessarily posed by collectives, but insist that the moral basis for the killing in war is blind to this collective aspect and recognizes, so to say, only individuals.

If, at the end of the day, the conditions for the permission to kill human beings in war are the same as those required for individual self-defense, then we have to be able to justify ourselves in the world to come, and to do so we have to show that that individual was posing (probably with others) an unjust threat, that he was morally responsible for doing so, that there was no other way of neutralizing the threat other than killing him, and that the killing was not disproportionate to the evil prevented.10 Since, in McMahan’s theory of self-defense, the aggressor’s moral responsibility plays a crucial role in making him liable to defensive attack, it is morally better to kill the person who is responsible for initiating some unjust threat than to kill the person who, at a given point in time, poses the threat, but bears less responsibility for it (acting, for instance, out of excusable ignorance).11

The requirement to justify each instance of killing in war on the basis of the same conditions used to justify killing outside the context of war is why I name this position “individualist.” As McMahan shows at length, it leads to a refutation of the fundamental tenets of traditional JWT, of which I shall mention only one. Since many civilians, such as politicians, people in the media, or religious authorities bear higher responsibility for the aggression of their country than 18-year-old soldiers thrown into the battlefield, the former might be more liable to attack than the latter, a claim which undermines the most fundamental requirement of jus in bello, namely, to maintain a strict distinction in warfare between combatants and noncombatants.

This brief presentation of McMahan’s view refers to what he calls “the deep morality of war,”12 which, I believe, is the morality we should consult if we want to understand the deep morality of TK. In McMahan’s view, this deep morality need not shape the actual laws of war. We will have to see later whether this dual morality—deep and shallow (so to speak)—is relevant to TK too.

I turn now to Collectivism. On this model, it is metaphysically false to describe wars in purely individualist terms. In war, as Noam Zohar puts it, “it is a collective that defends itself against attack from another collective, rather than simply many individuals protecting their lives in a set of individual confrontations.”13 Wars are irreducibly both collectivist and individualist; they are conflicts between collectives, but they are initiated and fought by individual members of the respective collectives. This dual reality, suggests Zohar, yields a dual morality, one that respects these two aspects of war.

What does this mean in practice? Zohar’s basic idea is that some members of a collective can be seen as identifying with it, or as officially (or half-officially) representing it. This is particularly true of soldiers, those individuals selected by the state to represent it, so to say, in the violent encounter with its enemies. When we kill soldiers, we do not kill them qua individuals, but qua agents of the enemy collective. We are under the reign of the collective aspect of war. By contrast, in dealing with civilians, we retain the individualist prism, which implies that it would rarely be permissible to target them. While, for McMahan, the key factor for making any individual a legitimate target in war is responsibility, for Zohar “the key factor is participation: combatants are those marked as participating in the collective war effort, whereas the rest of the enemy society retain their exclusive status as individuals.”14 For McMahan, the reason we are usually allowed to attack combatants, but not noncombatants, is that the former tend to be more morally liable than the latter. For Zohar, it is because in attacking the former we are allowed—even obliged—to take the collectivist perspective and ignore questions about individual liability, while in attacking the latter, individualist liability seriously constrains what we might do.

Note that, in Zohar’s view, when the relevant morality is not dual, namely, when only the individual perspective applies, what determines liability to defensive attack is moral responsibility. It is because most soldiers are below the threshold of responsibility required to make them liable to attack that we need the collective perspective to explain how killing them might be permissible.

I turn finally to Contractualism, recently developed at length by Yitzhak Benbaji.15 On this model, the most central aspects of jus in bello are based on a tacit agreement between states as to how wars should be conducted. The agreement is made ex ante, and it is binding because it is mutually beneficial and fair. The basic idea is that states have an interest in reducing the horrors of war without thereby preventing themselves from effectively defending themselves against aggression. So they agree in advance that combatants may be attacked with almost no restrictions, while noncombatants may not be (directly) attacked, with almost no exceptions. This involves a tacit agreement on the part of combatants to give up their natural right not to be attacked. By giving up this right, they thereby grant the other side moral license to kill them in warfare, license that is independent of whether the war fought by the other side is just or not. Soldiers marching into battle (to use an image from old wars) are like boxers entering the ring. In both cases, the harm to which they are morally vulnerable has nothing to do with individual desert or liability, and everything to do with a reciprocal forfeiture of rights.

That some aspects of the rules of engagement are a matter of convention is undeniable. For example, while it is forbidden to shoot pilots bailing out of crippled aircraft unless upon landing they refuse to surrender,16 there is no similar rule restricting the shooting of soldiers attempting to escape from burning tanks. And while the use of blinding lasers in battle is not permitted, the use of other weapons which can cause very serious injuries, including blindness, is allowed.17 If such rules are to be respected, it is only by virtue of their being accepted and followed by all parties to the conflict.18 The novelty of Contractualism is the idea that such conventions about warfare are not the exception but the rule; that the most basic elements of the in bello code are anchored in a tacit contract between the warring parties.

A common response to Contractualism is that if the in bello rules are “mere conventions,” then they do not carry serious moral weight. But, as emphasized by Waldron, conventions might be in some sense arbitrary, but nevertheless are very serious—deadly serious.19 A good example is the UK convention to drive on the left. This is indeed a “mere” convention, but once it is accepted and followed by the community of drivers, there exists a powerful moral reason to comply with it, even in circumstances in which one can benefit from driving on the right. The same applies with the rules of engagement: although most of them are grounded in a convention, there is a very strong moral reason for nations to stick to them in warfare.

It is important to realize, as will become clear in the next section, that all models accept what I shall call “The Responsibility Condition [RC]” for liability to attack, though they diverge in the way they understand its application. Assume that the other conditions for self-defense are satisfied (unjust threat, success, necessity, and proportionality). According to Individualism, RC would then be both a necessary and a sufficient condition to liability to attack in self-defense. According to Collectivism, it would be a sufficient condition, but not a necessary one (combatants are all liable to attack, although many of them do not satisfy RC). According to Contractualism, in a pre-contract world (a state of nature), RC is both necessary and sufficient for liability while in a post-contract world, it is neither necessary nor sufficient; combatants may all be attacked, although many are below the threshold of moral responsibility, while noncombatants may never be (directly) attacked, though many of them are above the required threshold.

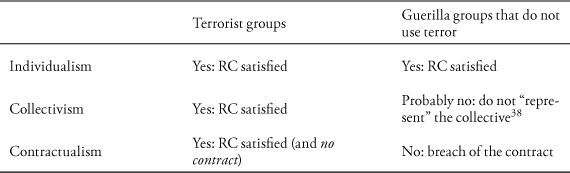

Table 1 The moral status of combatants and noncombatants

Let me then summarize the way these models substantiate the discrimination principle. We should distinguish three groups: innocents, such as young children, who pose no threat at all and are, in any case, below the threshold of moral responsibility; adult noncombatants, some of whom could be thought to culpably contribute to the unjust threat posed by their countries; and combatants. All three models agree that, regarding innocents, the regular presumption against killing human beings is at work, hence they are clearly morally immune to (direct) attack. All three models also accept the traditional distinction between combatants, who may be attacked, and noncombatants, who may not. The reasons they offer for this distinction are presented in Table 1 above.

Finally, how important is it, morally speaking, for each of these models, whether a given situation is defined as war or not? According to Individualism, such definition seems to bear no moral significance. Since the moral principles that govern wars are precisely the same as those that govern self-defense in conflicts between individuals, or between groups of individuals, saying that we are “at war” makes no moral difference. I would go further to speculate that for philosophers like McMahan such definitions should always be treated with suspicion, and as attempts to obtain wider moral permissions than those one is entitled to; that is, those entailed by the standard conditions for legitimate self-defense.20 By contrast, Collectivism seems to assign crucial significance to such definition. Since wars are (violent) conflicts between collectives and since collective morality is activated only in such circumstances, whether or not a conflict is defined as war makes all the difference. If it is war, then a whole category of people—the category of combatants—thereby loses its moral immunity from attack. (Thus, according to Collectivism, whether TK is a domestic, law-enforcing tactic, or an act of warfare against an enemy collective is indeed a central question.) For Contractualism too, defining a conflict as war is morally critical because only in war is the in bello contract activated with its special permissions (to kill all combatants) and restrictions (not to attack noncombatants). The contract is between states and it concerns violent conflicts between them, namely wars. According to both Collectivism and Contractualism, when war breaks out, a whole new moral perspective comes to light, one which has radical implications for what we may or may not do.

What does each of these models entail with regard to the legitimacy of TK? Let’s start by reminding ourselves that TK has been used by both Israel and the United States against individuals identified as playing a significant role in initiating and posing perceived unjust threats, some of them against civilians (“terror attacks”), others against military targets (“guerilla attacks”). At least in the case of Israel, even opponents of TK admit that the accuracy of identification has been very good.21 As emphasized above, these individuals tend to bear full moral responsibility for the attacks that they pose. On the face of it, this would be sufficient to show that the objects of TK cannot enjoy the immunity granted to those in the second row (“noncombatants”) of the above table, which implies that they fall within the terms of the first row (“combatants”), hence are morally liable to attack. However, such a move would ignore the fact that, after all, the victims of TK are not soldiers in the usual sense of the word. Moreover, some objects of TK had no direct involvement in military activity, such as Sheikh Ahmad Yassin, the founder and spiritual leader of Hamas, killed by Israel in 2004. Whether or not this fact makes a difference depends, as we shall now see, on which model of JWT is adopted.

According to Individualism, the crucial condition that must be satisfied to justify killing human beings in self-defense is that they are morally responsible for some grave threat whose neutralization is the end in mind.22 From this point of view, the formal affiliation of such people with some organization, or even some state, plays no intrinsic role in making them lose their moral immunity to being attacked. To be sure, often such affiliation indicates some kind of causal connection to the unjust threat, for instance, in the case of a member of an army or of some other security body. But one could pose an unjust threat to an individual or to a nation even without such membership, and one could be a member of the army—a soldier—and make no contribution, or even, in fact, a negative contribution to the threat posed by one’s army. (Think of a soldier who spends most of his term in jail because of breaches in discipline, or simply think of a lousy soldier.)

It follows that, on this model, the very fact that activists of Hamas and Al Qaeda are not soldiers in the usual sense of the word makes no difference to their moral status vis-à-vis the potential victims of the threats that they (individually or collectively) pose. Hence, if the only way to block such threats is to kill these activists, there is no reason to see why, according to McMahan and other supporters of Individualism, the use of targeted killing should be impermissible. Moreover, given the voluntary nature of enlisting in these organizations and acting within them, it seems that their members, or activists, are typically more liable to defensive attack than conscripted soldiers in regular armies, whose responsibility for their participation in unjust wars is rather weak. Hence, if the latter are legitimate targets for attack, a point on which all non-pacifists agree, the former are certainly so as well.

We can now see how, within the individualist view, TK is not just one permissible tactic among others, but the preferred one (unless it happens to be impractical or ineffective).23 It does a much better job of distributing the self-defensive harm in accordance with moral responsibility. We must always bear in mind that, in response to a perceived unjust attack, the alternative to targeted killing is not no killing, namely some form of pacifism, but non-targeted killing, namely, ordinary military operations which cannot be as sensitive to the differences in moral liability between the activists or combatants on the other side. For McMahan, a targeted killing of 50 initiators and central pursuers of unjust attacks is surely much better, from a moral point of view, than killing the same number of combatants—and probably many more—in a regular military operation.

I mentioned earlier that most of the debate about the legitimacy of TK focuses on the question of whether TK should be understood within the law-enforcement or within the armed conflict model. We can now see that insofar as the deep morality of self-defense is concerned (as interpreted by Individualism), this distinction is quite shallow. What makes a person liable to defensive attack is the fact that he or she satisfies the conditions mentioned above (moral responsibility for an unjust attack, etc), and these conditions are indifferent to whether the threat he or she presents (or is responsible for) is posed on the interstate or the intrastate level; whether it is posed as part of a conflict between two individuals, or between two groups of individuals. If it is morally permissible to use TK against the leaders of some military or semi-military organization, it must be because of the gravity of the unjust threat they pose, their moral responsibility for posing it and the inability of the state to neutralize the threat by other means. But surely the same considerations could at times justify the use of TK against some leaders of the mafia too. The current struggle of the Mexican government against the drug industry and against the criminal activity around it might be a case in point.

The conclusion regarding the in-principle legitimacy of using TK even against criminals sounds rather scary, and this is precisely where consequentialist considerations, which, for McMahan, are not part of the “deep morality,” kick in. Imagine two similar threats to innocent lives, one posed by an in-state criminal and the other by an out-state terrorist. Suppose that these are circumstances in which it would be permissible to kill the terrorist. It might nevertheless be forbidden to do so in case of the in-state criminal, because of the potentially disastrous ramifications to the rule of law. But would such considerations rule out TK in the context of wars against guerilla or terror organizations too? In arguing that the laws of war need not match the deep morality of war, McMahan seems to open the door to a positive answer to this question. However, the arguments he offers for this mismatch do not seem to apply to the type of conflicts in which TK is being used; that is, conflicts between states like the United States or Israel and organizations such as Al Qaeda and Hamas. In McMahan’s view, “it is dangerous to tamper with rules that already command a high degree of allegiance. The stakes are too high to allow for much experimentation with alternatives.”24 This is a fair consideration, but it seems irrelevant to the war against organizations such as Al Qaeda and Hamas, which have already seriously tampered with these rules. When one side stops playing by the rules, it is hard to see the further danger which is created when the other side does so too (except for the danger to the first side, of course). In response, one might argue that the danger McMahan has in mind is not the moral escalation that might accrue as a result of changing the laws of war in the context of some particular conflict between, say, the United States and Al Qaeda, but the escalation that might follow regarding wars in general. That Al Qaeda violates the accepted rules of warfare and directly attacks civilians is one thing. That the United States should do so is entirely different and might seriously destabilize the widely accepted conventions of warfare. I see two difficulties with this response. First, I think that the international community—justifiably or not—sees conflicts with such organizations as different (or “unique”) and hence, in practice, is not likely to apply the rules and practices that are used in them to regular wars. Second, even if the danger of such escalation was realistic, I am not sure that it is fair to expect the United States (or any other country) to follow rules that are not mandated by the deep morality of war just in order to minimize the risk of escalation to other countries and to the international community in general.

Let us turn now to Collectivism and see what it implies regarding TK. Recall that under this model, even combatants would not be legitimate targets for lethal attack if judged by their personal blame only. If we relied exclusively on the principles of individual morality, pacifism would probably be the only respectable option. However, wars are not only conflicts between individuals—those who actually drop bombs, throw hand-grenades, and fire missiles—but also, essentially, between collectives. When we kill enemy soldiers, we do not kill them qua individuals attacking us, but qua representatives of our enemy, and such killing is permissible only because it expresses the collectivist aspect of war.

Is, then, the American campaign against Al Qaeda a war in the relevant sense, namely a conflict between collectives? To simplify, let us ignore the other allies and assume that it is just the United States versus Al Qaeda. The United States would definitely qualify as a collective in the required sense and, as a result, its soldiers would be legitimate targets in any war situation.25 But what about Al Qaeda? Though Al Qaeda did attempt to claim that it was acting in the name of all Muslims, the claim was obviously groundless. First, as various polls and surveys demonstrated, an overwhelming majority of Muslims objects to Al Qaeda’s tactics.26 Second, and more importantly, even those who support Al Qaeda cannot be said to constitute a collective in the sense of the model we are discussing. Surely a collective in this sense is more than a group of people who happen to share a view about some issue. It must be a group of people with “thick” connections between them, people with some kind of a shared memory, with shared aspirations, people who perceive themselves as members of the same group. The metaphysical claim that the existence of a collective cannot be reduced to that of the individuals comprising it cannot be applied to just any group of people sharing some feature (playing bridge together every Sunday, admiring John Lennon, or hating the United States). There is, therefore, no collective that Al Qaeda can reasonably be said to represent that would make its members or activists liable to lethal attacks in the way proposed by Collectivism.

A possible response to this argument would be to give up the requirement of representation and suggest that the collective assumed by the model at hand is not the nation but its army. Indeed, in his later work, Zohar explicitly takes this line against his initial view.27 Applying it to the present context would yield the conclusion that Al Qaeda should be regarded as a collective, which would mean that its members may be intentionally killed regardless of their individual responsibility.

I see two difficulties with this revised version of Collectivism. First, if the collective entity is the violent organization that threatens us, then, by the same token, this would apply to intra-state groups too, such as the mafia, or local gangs of criminals, whose actions therefore cannot be reduced to those of their individual members. That would legitimize the use of military measures in general, and TK in particular, against members of such organizations, regardless of their individual responsibility, a conclusion that very few would accept. Second, even if the army we are fighting against should be regarded as a collective, that should not change the obvious fact that—in standard wars—we are also fighting against some nation or some state. We would then need some account of the relation between the two collectives we are fighting against (the nation and its army), and the notion of representation seems to come back as a natural answer.

There is more to say about the merits of these two versions of Collectivism, but this would not be necessary in order to determine the legitimacy of TK against Al Qaeda. If Al Qaeda is a collective in the sense required by Collectivism, then clearly the use of TK against any of its members would be legitimate. But even if not, the same conclusion follows. Recall that the collective perspective in war does not replace the individualist one, but rather supplements it, thus turning what otherwise would be illegitimate killing to legitimate. As mentioned earlier, the reason that such killing would be illegitimate has to do with the reduced responsibility of young conscripted soldiers. But this reason does not apply to Al Qaeda activists, hence individualist morality would be sufficient to justify the use of TK against them, just like in Individualism.

The case of Al Qaeda produces a special challenge to Collectivism because Al Qaeda cannot be reasonably said to stand for an independently defined collective which is in a state of conflict—at war—with the United States. But what about Hamas? In the case of Hamas, it does make sense to see its activists as acting on behalf of the Palestinians in their conflict with the Israelis in a way that fits the framework Collectivism has in mind. All the more so if one sees the military activists of Hamas as representing not the Palestinians in general, but those living in the Gaza Strip, over which Hamas has had effective control since 2007. What implications does this state of affairs have with regard to the binding rules of warfare in general, and to the use of TK in particular?

From the point of view of Collectivism, the answer seems to be straightforward. If Israel and the Hamas semi-state in Gaza28 are at war, then the combatants of one side—IDF soldiers and Hamas activists, respectively—are permitted to kill the combatants of the other side even if the latter have only diminished responsibility, or even no responsibility at all, for the aggression mounted by their collectives. Just like in conventional wars, this permission is almost unconstrained. Thus, if Hamas is permitted to kill any Israeli soldier, even a conscripted 18-year-old one, it is definitely permitted to use TK against key figures in the Israeli army, officers and commanders, who bear more responsibility for the perceived threat against the Palestinians and play a more central role in its implementation; the permission would also apply to the similar use of TK on the part of Israel.

It seems, then, that the addition of the collectivist perspective makes the use of TK against national organizations such as Hamas29 even easier to justify than it would have been without this perspective. Since most of Hamas activists are not conscripted,30 they typically bear enough moral responsibility to make them legitimate targets for lethal attack even if viewed as individuals. That they can—and ought to—be seen also as agents of the Palestinian collective makes their killing even more legitimate.

Finally, what would Collectivism say about the targeted killing of political leaders, the paradigmatic case of assassination? Zohar clearly wishes to limit the group of those “subsuming under their collective identity,”31 and who are therefore legitimate targets for lethal attack, to enemy combatants, which would rule out the killing of politicians. Yet it seems to me that the logic of his argument could easily be interpreted as including politicians too. After all, there is no person who represents a nation, expresses its identity and acts on its behalf better than its prime minister, president or king. This is why wars are often described as against the leaders of the enemy collective, for example, “the war against Hitler.”32 It would thus make perfect sense to say that when we kill such leaders we are thereby expressing our recognition of the collectivist aspect of the conflict. To be sure, there might be good pragmatic reasons to refrain from such a policy, which Collectivism too could appreciate. But in terms of the deep morality of war, with its individualist and collectivist levels, even targeting politicians would be a legitimate act of war.

Let’s turn to the last model I analyzed above, the contractualist one. Although proponents of Contractualism about wars often regard states as the only parties to the contract, there seems to be no reason to limit the parties to the contract in this way. The fundamental logic of Contractualism applies to all groups that realize that one day they might have to defend themselves by force. They all share an interest in adopting rules that would reduce the horrors of war without making effective defense impossible. In other words, the in bello contract is ex ante mutually beneficial and fair not only for states, but also for national liberation movements, and for all groups that fight against oppression and discrimination.

However, such groups might opt out from the contract, or not enter into it, if the behavior of the other side manifests no respect for the accepted conventions. When this is the case, then the in bello contract is not activated, so to speak, because no individual will resign his or her fundamental rights, especially the right to life, without a reciprocal resignation by the other relevant parties, and no state has authority to offer such resignation in the name of its citizens. The fact that the in bello contract is not activated does not mean that, morally speaking, everything is up for grabs. Even in such grim circumstances, the fundamental rights of people maintain their force; it is still forbidden to rape women, to bomb kindergartens, to torture prisoners.

The first thing we should ask about TK is whether its wrongness, if it is wrong, belongs to the category of non-conventional wrongs like rape and torture, or to that of conventional wrongs (that is, actions made wrong merely as a result of a convention) like the prohibition against shooting pilots parachuting from their aircraft, or against directly killing noncombatants. I think it is immediately obvious that TK does not belong to the former. As emphasized throughout the chapter, TK is aimed at people who are actively involved in planning and carrying out perceived unjust threats to other people, hence they are liable to defensive attack against them. Moreover, they seem more liable than plain soldiers in regular wars, the killing of whom is never seriously put in question. Hence, if TK is wrong, it is only conventionally so; wrong because of an accepted convention against it.

This conclusion is sufficient to show that, according to Contractualism, nothing could be wrong with the use of TK against organizations like Al Qaeda which have no respect for the conventions of warfare. Our moral obligations towards Al Qaeda are limited to non-conventional ones and TK is not among them.

But what about military groups that do show at least some respect for the war convention? Does the in bello contract—to which they are parties—forbid TK? The way to answer this question within a contractualist framework is to ask whether a rule forbidding TK is one that the parties to the contract would ex ante accept, which is the same as asking whether it is a rule that is mutually beneficial and fair. Imagine, then, that sitting around the table to review proposals for the in bello agreement are not only delegates of states but also of various guerilla organizations, mainly those fighting for national liberation. The states unanimously accept the discrimination principle, which grants all sides unrestricted permission to kill combatants while imposing upon them a strong prohibition against killing non-combatants. The natural right to life of combatants is compromised (all of them become legitimate targets regardless of the justness of their cause, their level of responsibility and so on) in order to guarantee the moral immunity of noncombatants (many of whom would be legitimate targets otherwise). Since wars are mainly clashes between combatants and not between civilians, this deal does not reduce the parties’ ability to achieve effective defense against those attacking them. Would the non-state parties join this deal?

In other words, TK seems perfectly compatible with the fundamental purpose of the in bello contract. It enables states to effectively defend themselves from the threats posed against them, without having to opt for full-scale war that, ex hypothesi, would be legitimate in the circumstances under discussion. Thus, not only would contractualism license TK, it would recommend it as a preferred tactic. Ex ante, the parties to the contract would find it mutually beneficial to adopt a rule that would lower the chances of a full-scale war by granting permission to all sides to utilize a whole battery of more limited military measures. The use of such measures would be much less destructive and lethal than war, and could provide decent, albeit imperfect, defense. (Remember that wars do not guarantee perfect defense either.)

Furthermore, assuming, as we did, that national liberation movements are sides to the in bello contract, we should assume that they must take into consideration not only their current, pre-state situation, but also their (hopefully, in their own eyes) post-state situation. They must envisage a scenario in which one day they themselves (that is, the nation-state they will found) may face threats of guerilla and terror attacks of precisely the same nature that they are at present posing to others. And when they reflect on such a scenario, they will surely see the advantage of a rule permitting the use of measures such as TK in order to avoid full-scale war.33

While Contractualism does not ground a prohibition on the use of TK against soldiers in regular armies, or fighters/activists in irregular armies (guerilla/terror organizations), it does ground a prohibition on the use of TK against political leaders. This follows from the basic logic that grounds the in bello agreement, namely, the wish to prevent total war. In this vein, each side renounces its natural right to kill those responsible for the unjust threat it faces, in return for a parallel renouncement by the other side. However, as emphasized above, such renouncement must be reciprocal. If one side frees itself from such an agreement, the other side is no longer bound by it. Political leaders who send their armies to fight unjust wars have no natural right not to be killed by the victims of their aggression.

A common complaint often voiced by terror or guerilla organizations is that of the conventions of warfare work to the advantage of strong parties—that is, the states—and are therefore unfair. To formulate the complaint in reference to the fundamental rationale of Contractualism: if such organizations were bound by these conventions, they would lose their ability to beat their enemies. Our enemy has aircrafts, tanks and drones, they say, while we only have homemade bombs to use against school buses, restaurants, and so on. If we are not allowed these measures, in effect we are prevented from defending our rights.

This complaint is not very convincing. Which constraints do such organizations think should be removed in order to achieve the assumed fairness? To judge by the examples just mentioned, examples which reflect the actual behavior of Al Qaeda and Hamas, these organizations would like to be exempted from the prohibition against intentionally attacking the innocent. But this prohibition is anchored in the natural rights of the potential victims, not in any kind of contract, and it is hardly ever overridden by other considerations. Hence, if the difficulties faced by guerilla and terror organizations to advance their goals have to do with constraints of this kind, the object of their complaints is not Contractualism.

They might still insist that the situation is unfair and redirect the complaint to natural morality. But that would amount to a plain rejection of morality. Unfortunately, in the actual world, the wicked often prosper, while the righteous fail. Often, at least in the short run, being loyal to morality—telling the truth, respecting the rights of workers, taking care of sick relatives—is hard, demanding, and not rewarding. Nevertheless, as Kant famously argued, such “subjective restrictions and hindrances” to the notion of duty, “far from concealing it, or rendering it unrecognizable, rather bring it out by contrast and make it shine forth so much the brighter.”34 That following morality puts one at a disadvantage is hardly ever a justification for evading its demands.

I should add that the idea that morality sometimes imposes a price upon us is built into the standard conditions for legitimate self-defense, conditions which quite obviously favor the strong (the aggressor) over the weak (the potential victim). This is most evident with the proportionality condition. Assume that the victim has no other way to defend herself but to do X, but that X would be disproportionate to the harm prevented. The proportionality condition requires that she refrain from X-ing, even though she will be harmed as a result, maybe with no remedy.

The unfairness complaint, then, cannot be taken to apply to the violation of natural rights. So maybe it applies to contractualist rights? Thus understood, the organizations under discussion would be asking for an exemption from the ban against killing noncombatants such as politicians or religious authorities, the killing of whom is ruled out by the in bello contract but not by natural morality. “We are too weak and technologically deprived to limit our attacks to military targets,” they would say, “hence fairness requires letting us target civilian targets (from the above groups and similar ones) as well.” This sounds like a reasonable position. In contractualist terms, it amounts to a refusal to join the contract that is perceived as not mutually beneficial. But, of course, not joining the contract is a double-edged sword; it relieves one of the duties imposed by it, but, at the same time, denies its benefits and protections. If guerilla and terror organizations attack civilians (of the kind that, in the circumstances, do not have a natural right not to be attacked), there is nothing unfair in the other side doing the same to them.35

At times, it seems that proponents of the unfairness argument rely on the idea that the very fact that side A loses shows that side B was stronger, which means that the terms of the competition must have been unfair; they enabled the strong side to overcome the weak side. This, of course, is absurd. It would entail the ridiculous conclusion that for the sake of fairness we would have to make sure in all competitions and conflicts that no side prevails.

In order to sharpen the question under discussion, I suggested we assume that the relevant circumstances are those in which a semi-military group unjustly attacks the military or civilian targets of some state. In an earlier paper,36 I argued that since, in such circumstances, almost all non-pacifists would concede that the attacked state has a right to launch a war, or a serious military operation against this group, they are forced to accept the legitimacy of TK which has clear moral advantages over the use of massive military force in the “old” way. In this chapter, I tried to strengthen this conclusion by showing how it follows from the main interpretations of just war theory today. I summarize the results of my discussion in these tables, Table 2 dealing with TK against militants, and Table 3 with TK against political or religious leaders.

Let me conclude with three final comments:

First, the permissibility referred to in these tables refers to the “deep morality of war,” which means, in the present context, the moral liability of TK victims to being attacked. Do other considerations, mainly of a consequentialist nature, make a difference to the final moral verdict? As I said earlier, I am somewhat skeptical. McMahan’s reason for resisting the consistent implications of the deep morality of war is that he finds it “dangerous to tamper with rules that already command a high degree of allegiance. The stakes are too high to allow for experimentation with alternatives.”39 However, we are currently in a world of “new wars,”40 and if there is one thing that is obvious about these wars it is that they do not have “rules that already command a high degree of allegiance.” Rules as well as practices are now in the making. Therefore, the danger that bothers McMahan seems less troublesome regarding the rules we construe for fighting these new wars—including those permitting TK.41

Table 2 Is TK permissible against fighters/military activists and why?

Table 3 Is TK permissible against political/religious leaders and why?

Second, opponents of TK are shocked by the apparent ease by which countries like the United States or Israel “execute” people with nothing remotely close to due process, and with no need to establish imminent danger or individual responsibility. From the perspective of domestic law-enforcement, this is indeed shocking. But from the perspective of war it is not shocking at all. This is precisely what war is about—killing enemy combatants with no due process and with hardly any constraints whatsoever. This might lead some readers to object to wars in general and opt for pacifism. That is a respectable option. This chapter, however, assumed a non-pacifist view and tried to show how the main theories that ground this view and permit the wholesale killing in war, also permit the use of TK. There is nothing about TK that is inconsistent with the main theories of just warfare.

Third, if indeed TK has such military and moral benefits,42 as I tried to show, and if it is compatible with all current versions of JWT, why do some circles express such strong opposition to it? One suspects that what often underlies this opposition is not a position on the level of jus in bello—that is, an objection to TK as a tactic of warfare—but a position at the level of jus ad bellum. This is confirmed by the surprisingly positive way TK was regarded in the recent war against Libya. As Anderson rightly remarks, “the speed and timing of this sudden new acceptance of drones in Libya raises questions as to what drove the change of heart.”43 In my view, what drove the change of heart was a change in the way the cause of the war was regarded, which helps to see that there was never a real problem with TK on the jus in bello level. At any rate, the war in Libya might have transformed the debate about TK. To cite again from Anderson: “Libya might have sanitized drones as a tool of overt, conventional war and might have shifted the debate over their abilities to be discriminating and sparing of civilians.”44