Conclusion

Looking the Other Way

[I]f the community is a source of power, then it could exercise this power for its own ends, rather than those of the state.

—Kristian Williams1

This book has traced the historical development of a number of lateral surveillance initiatives. The story I shared about police crowdsourcing, for example, examined how it developed from its origins in oral “cries” to its current manifestations in social media. My analysis of 911 technologies, too, traced them from the telegraph private boxes of the nineteenth century to today’s crime-reporting smartphone apps. Likewise, I traced the development of Neighborhood Watch in order to explore the ambivalent, uneasy relationship that citizens’ patrols have had with violence, surveillance, and communicative action. In Chapter Four, I turned to the development of youth police initiatives, emphasizing that the good neoliberal subject isn’t always an adult. The final case study, Chapter Five, re-centers our attention upon the state’s apparatuses of terror production and citizen mobilization. I decided to end with antiterrorist surveillance because it sheds unique light on “where we are” at the present cultural moment. While each of the chapters illustrates a unique present of citizen-surveillance campaigns, I think there is something uniquely contemporary—and uniquely troubling—about the trends we see in the War on Terror. As such, in my attempt to provide a history of our complex and contradictory present—with all its clashes over resistance and control—this particular slice of contemporary life seems like the best resting place for us to reflect on the cultural and political implications of current trends in seeing and saying. As the most visible, threatening, and controversial of today’s spy-and-snitch culture, it gives us a clear and specific object of critique—we can dispute its truth claims, rethink its constant production of internal and external enemies, resist the citizen-policing mentality on which it thrives, and anchor our response in coordinated acts of withdrawal and resistance. Therefore, while the “If You See Something, Say Something” campaign and allied initiatives do not provide a unified telos for the diverse practices of surveillance and communication detailed in the book, by placing them alongside an extensive history of citizen responsibilization campaigns we can map these programs’ points of convergence. Most of all, by epitomizing the inherent political danger of lateral surveillance practices, current antiterrorist initiatives allow us to reorient our story toward how we can recapture our sight and speech in the service of a more promising future.

From this perspective, then, the question of the future converges with the question of resistance. These stories, situated within new historical networks and placed upon new planes of intelligibility, are meant to reassemble the past in such a way that the present is recognized for all its contingency. In an interview on his “genealogical” method of historical analysis, Foucault remarked, “[T]he question I start off with is: what are we and what are we today? What is this instant that is ours? Therefore, if you like, it is a history that starts off from this present day actuality.”2 The represented past is the terrain on which we battle to better understand the challenges of this “present day actuality.” Thus throughout the book I have taken pains to show how resistance movements, hackers, prankers, activists, criminals, and rebellious kids have complicated the state’s regimes of citizen responsibilization. These points of misfire, struggle, and compromise illustrate the contingency and fragility of present citizen-surveillance programs. Reconfiguring how the past gave way to the present, therefore, helps us design new ejection seats as we find ourselves gliding along toward troubling futures. Surveillance scholars, for their part, have done a pretty impressive job of outlining ways to subvert the surveillance rituals demanded by the state and by digital capitalism. Disabling surveillance cameras,3 participating in effective anti-surveillance groups like the ACLU,4 and even “turning off all media”5 have been proposed as worthwhile ways to resist the surveillance and datafication of our everyday lives. While these ideas provide some useful and provocative suggestions for how to resist becoming the objects of surveillance, they do not give us much guidance in how to resist becoming the subjects of surveillance. Yet in the present cultural climate, not only do we need to learn how to resist abusive surveillance practices, we also need to examine how to look the other way—that is, how to turn our eyes away from our peers and, in so doing, reenvision how we fit into the world around us.

Toward this purpose, I would like to discuss three political possibilities opened up by my analysis (although I hope there are many others, only some of which have been detailed in earlier chapters). While I find all three to be legitimate in certain social conditions, they are rooted in different theoretical and political commitments. Because of these differences, they offer somewhat opposed, and perhaps even contradictory, visions of political action. Thus in lieu of outlining a coherent, normative project of resistant action, I will reflect on how these three different responses offer potentially valuable ways to resist the pervasive call to police our peers through surveillance and communication.

Silence

This book has explored a key way in which power circulates in a liberal society like the United States: through the programs and schemes by which citizens are finessed into policing themselves and others. In order for the liberal project to function, therefore, it doesn’t just need our consent—it needs our participation. This complicated liberal mixture of atomism and civic responsibility thrives on vigilance and suspicion—they are, in fact, two of its essential ingredients. So if we find that our seeing/saying bodies have been activated in these struggles for the production of vigilance and suspicion, perhaps the best way to resist is to find means of productive disengagement—that is, to short-circuit these demands on our surveillance and communication through silence.

Let me emphasize at the outset, though, that this cannot be a politically debilitated silence, as if one had been forced into shutting up and shutting down.6 Rather, the silence we might seek is an affirmative quietude—in the words of Nick Dyer-Witheford and Greig de Peuter, “a defection that is not just negative but a project of reconstruction”7—that deprives liberal police power of its means of sustenance. If we are commanded to call the cops on our neighbors and family members, to send anonymous text messages that snitch on our fellow students, to scour our gated communities with little two-way radios, to rat out our parents for smoking pot, or to report every suspicious activity in sight, perhaps shutting up is the most radical and socially responsible course of action available to us. As I’ve argued throughout this book, in order for us to be governed through crime and terror, we have to be converted into speaking subjects. Thus if we remain silent when we encounter difference among our neighbors, colleagues, friends, and family—i.e., if we learn to look the other way—this sort of social regulation simply can’t take place.

A number of theorists have proposed this very solution to capitalist demands on communicative labor. But as communicative labor has become a central demand of liberal citizenship, the autonomists’ traditional critique can apply just as well to civic political relations. When Maurizio Lazzaratto writes, “Capital wants a situation where command resides within the subject him- or herself, and within the communicative process,”8 we can extend this analysis to the processes by which private and civil authorities profit by instilling into everyday citizens this disciplined impulse to say something. For Lazzaratto, this capture of communicative labor thrives on an “authoritarian discourse” that demands we speak: “we have here a discourse that is authoritarian: one has to express oneself, one has to speak, communicate, cooperate, and so forth.”9 For the good of the homeland, for the good of the community, for the good of the children, for the good of the vulnerable—we are urged everyday to speak and to speak. Yet if we wish to be governed differently, we need to recognize that, in the words of Ronald Greene, “the political dimension of communicative labor is built into bio-political production’s attempt to harness and capture the constitutive power of communication.”10 In the face of this ongoing capture, Greene advocates a “generalized refusal or defection from the commands of money/speech.”11 Greene, therefore, urges us to withhold our communicative labor in order to throw a monkey wrench into liberal capitalism’s intensive machinery of capture.

Armand Mattelart, too, has voiced sympathies with this view, suggesting that we withdraw our communicative labor from apparatuses of citizen production: “the key thing may be to create spaces of non-communication, circuit breakers, so we can elude control.”12 Creating affirmative spaces of noncommunication, therefore, forestalls the conversion of our seeing/saying bodies into sheer biopower for the countless authorities and institutions who foster social regulation through casual, ongoing expressions of suspicion, intolerance, and ostracism. Now that we are trained to see all activities and everyday items as suspicious and potentially threatening to the very social order, when you see something, don’t say anything. Create what Gilles Deleuze called “vacuoles of noncommunication”:13 refuse to police your neighbors, your coworkers, and even strangers whose behavior you might not understand. In a society where we are more than three times as likely to die from a lightning bolt than a terrorist attack, we need to rediscover our comfort with the “unknown unknown,” as former secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld put it.14 We need to learn to look the other way, without fear or opportunistic suspicion. In a security society that demands our communicative labor for its very political sustenance, silence is often a radical move.

Solidarity

As it is popularly told, the infamous 1964 Kitty Genovese murder story might seem to contradict my findings about the cultural impulse to see something and say something. The original news account, as published in the New York Times, reported that thirty-eight bystanders looked on as Kitty Genovese, a twenty-nine-year-old Queens woman, was raped and murdered nearby. The Times described, “For more than half an hour thirty-eight respectable, law-abiding citizens in Queens watched a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks in Kew Gardens. . . . Not one person telephoned the police during the assault; one witness called after the woman was dead.”15 Yet as journalists and researchers have recently discovered, this popular narrative was more fiction than fact.16 Indeed, one of Genovese’s neighbors, Robert Mozer, yelled at the attacker and momentarily scared him away. A neighbor and friend of Genovese, Karl Ross, opened his apartment door just in time to see the stabbing; instead of assisting the dying woman, Ross fled his apartment through a window but did call the police. Genovese eventually died in the arms of a young woman who, after listening to Genovese being attacked for half an hour, finally walked outside to soothe her as she died.

A. M. Rosenthal, an executive editor of the Times, later authored a book about the murder in which he diagnoses the social ills that led to Genovese’s death. Rosenthal essentially repeats the description in his newspaper’s original report: “thirty-eight of her neighbors had seen her stabbed or heard her cries, and that not one of them, during that hideous half-hour, had lifted the telephone in the safety of his own apartment to call the police and try to save her life.”17 Waxing philosophical on the bigger picture of American alienation and atomism, Rosenthal suggests, “[I]n dying she gave every human being . . . an opportunity to examine some truths about the nature of apathy.”18 Yet when Rosenthal alleges that Genovese’s “neighbors heard her scream her last half hour away and did nothing, nothing at all, to give her succor or even cry alarm,”19 he is only half right. Her neighbors did, in fact, cry alarm—several of them called the cops and yelled at the attacker. But that’s all they did. They associated neighborly duty with calling the police. Their neighborly responsibility, therefore, had been successfully transformed into civic responsibility, placing the state in the center of their social obligations. So they called the police and waited inside their comfortable homes, listening to their young neighbor scream until an ambulance and the police arrived in just enough time to cart off Genovese on a stretcher.

Contrary to Rosenthal’s claims, then, the Genovese case is less indicative of social apathy than of the cultivation of a very particular sort of community responsibility. Rather than take direct action to save their friend and neighbor—whose attacker had a knife, not a gun—they did the civically responsible thing by calling the cops and hoping that the police would confront the attacker and save Genovese. What this illustrates, then, is not that citizens are apathetic or that they’re “bad Samaritans”; rather, it demonstrates how the introduction of the home telephone allowed citizens’ social responsibility to be rerouted through the police. The phone and allied media technologies provide the technical conditions in which citizens can be passively engaged in the safety and well being of their neighbors by deferring direct action to a centralized police force. In fact, as New Yorker journalist Nicholas Lemann remarked in his 2014 reflection on the Genovese case, the city’s response was to institute 911 as the nationally standardized emergency number.20 The city’s response, then, was to make it easier for citizens to call the cops. (Despite the fact, of course, that Genovese’s neighbors had called the local police department, but the cops were simply too slow to save Genovese.)

While the telephone and other media devices have allowed us to more easily see something and say something, the Genovese case provides an unsettling example of how these technologies have helped transform our social responsibility into civic responsibility. Accordingly, it demonstrates how the phone and other technologies have distanced us from our neighbors by discouraging direct local action. While Sherry Turkle21 and other critics have recognized that today these technologies separate us from one another by making screens and distractions ubiquitous, I am describing a different sort of separation—a separation by which these devices have allowed the police apparatus to colonize our social responsibility, such that our first impulse is not to help our neighbors when they’re in trouble, but to call the cops. But there are times when our communities demand social action that is not filtered through the state, when we should participate in local acts of what Paolo Virno calls “nonservile virtuosity.”22 We should cultivate direct forms of community solidarity—not vigilant, suspicious ones that involve scouring our communities for petty criminals (à la George Zimmerman), but an openness to and care for our neighbors that would make it unthinkable to sit indoors while they were being murdered right outside. As Harvey Molotch has argued, we need to develop forms of solidarity that are not rooted in the vigilance of Neighborhood Watch and homeland security initiatives: “Very often . . . the need is to be proactive, but in a different direction than is ordinarily undertaken in the realm of official security. One should move forward to relax, assist, and to set up ways for people to make good on their inclination to come to one another’s support and rescue.”23 Indeed, our mission to find new forms of direct communal action that eschew suspicion, vigilance, and the state’s rechanneling of our social responsibility confronts us with a difficult task. But it is a task that must be carried out.

Knowing When to Say When: Sousveillance

Despite the social and political dangers inherent in any seeing/saying initiative, the present confluence of preemptive security logics, lateral surveillance culture, and mobile technologies allows for productive avenues of resistance. There are ways in which the technologization of the American citizenry can be used to actively counter the abuses of the police and other individuals in positions of power. New trends in “sousveillance”—the methods by which individuals carry out “bottom-up” surveillance, typically through new technologies—have freed citizens to turn their gaze against the state, allowing them to capture and publicize police brutality and other offenses.24 In fact, the widespread popularity of mobile surveillance devices has empowered citizens while it has simultaneously disciplined their conduct: nowadays everyone, including police officers, is under threat of constant surveillance by mobile phones and other devices equipped with video and audio recording capabilities.25

When CIA contractor Edward Snowden released several million intelligence files to Guardian journalist Glenn Greenwald, he forced the issue of pervasive surveillance into the open. In the wake of Snowden’s revelations, polls found that a majority of the American public approved of the NSA’s dragnet surveillance measures. As time has progressed, however, the American consensus has evolved significantly: a Pew Research study released in 2015 showed that a majority of Americans, fifty-seven percent vs. forty percent, disapproved of the massive federal surveillance of U.S. citizens.26 As the Snowden revelations have sunken deeply into political discourse, Americans have become increasingly wary of the state’s shadowy data collection programs. Despite President Obama’s attempts to ensure the American people that “their rights are being protected, even as our intelligence and law enforcement agencies maintain the tools they need to keep us safe,”27 most Americans simply aren’t buying it. Combined with the growing arrogance and invasiveness of DHS surveillance programs and the TSA’s humiliating security theater, the “Snowden Revolution”28 has helped make possible a political sea change. Conservative Republicans like senators Rand Paul (KY) and Ted Cruz (TX) are joining with progressive Democrats like Mark Udall (CO), Ron Wyden (OR), and Martin Heinrich (NM) in order to haul in the out-of-control and unaccountable domestic surveillance apparatus. While their efforts have not had a significant impact on the U.S.’s domestic surveillance policy, Snowden’s own brand of seeing and saying has once again made opposing state surveillance a politically profitable stance.

The Snowden revelations present us with an opportunity to clarify a positive political vision of seeing and saying in the contemporary American moment. Snowden’s recording and transmission of classified American intelligence files was not a product of the kind of citizen-to-citizen lateral surveillance I’ve outlined in this book. On the contrary, his activities illustrate how citizens can turn their trained and technologized bodies against corrupt authorities. Like Snowden, many courageous whistleblowers, investigative journalists, and other citizens investigate and publicize the abuses of capital and the state. Rather than aiming a suspicious eye at their fellow citizens, whistleblowers like Snowden demonstrate how vigilant citizenship need not be translated into the kinds of lateral surveillance hysteria we see with Neighborhood Watch, D.A.R.E., and the “If You See Something, Say Something” campaign. This, I argue, forms an important line of distinction between lateral surveillance and sousveillance: while lateral surveillance turns citizens against one another, sousveillance—at least in theory—allows citizens to unite against power.

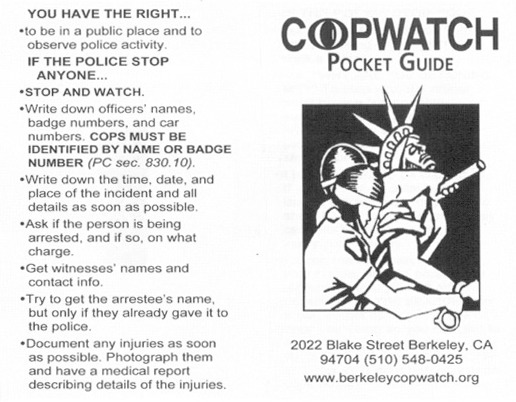

Although there are countless politically diverse organizations and professional communities that carry out innovative sousveillance work—such as the previously discussed Cop Block and the Huey P. Newton Gun Club—Copwatch provides an especially interesting grassroots example. Founded in 1990 in Berkeley, Copwatch began by organizing street patrols to document police abuses.29 Within months, the group was holding “Know Your Rights” training seminars that instructed citizens in the legal limits of police power (and, of course, in legal methods for carrying out sousveillance of police officers). In addition to frequent protests, national conferences, and community events, Copwatch released a training video, These Streets Are Watching, in 2003, which was accompanied by lesson plans for school children that covered the Bill of Rights and civil liberties.30 These innovative activities not only succeeded in raising awareness of police brutality, they also publicized legislative efforts to suppress sousveillance of police officers. As Copwatch and other activists point out, officers routinely confiscate video cameras, phones, and other recording devices that are being used to document police abuses. The right to record cops has thus become a serious bone of legal contention, as a number of jurisdictions (such as Atlanta and New Haven, Connecticut) have declared citizens’ rights to capture footage of the police. Yet some states, such as Illinois, Maryland, and Massachusetts, have reinterpreted the law in order to prevent citizens from monitoring cops. (Some have even invoked “homeland security” in doing so.)31

Figure C.1. Taking on police brutality with surveillance and communication. Copwatch Pocket Guide, www.berkeleycopwatch.org.

Despite these legal controversies, Copwatch and likeminded citizens have effectively used cutting-edge media technologies to record and publicize police brutality. As the late Jim Aune reminded us, we shouldn’t lose sight of the positive political potential of new media: “every technology simultaneously opens up possibilities of emancipation and domination.”32 Although much of this book has focused on the dangers and political ambivalence of new surveillance and communication technologies, this emancipatory potential is clear in the many ways that citizens have used mobile media to carry out important acts of sousveillance: from the Rodney King beating in 1991 to the 2009 Oscar Grant shooting, and in countless episodes since the widespread emergence of the smartphone, cop watchers have used their technologized bodies to bring legal accountability to an increasingly violent and repressive police apparatus.33 This trend in sousveillance, in fact, is gaining significant cultural ground: the ACLU, for example, has developed a smartphone app that lets citizens secretly record traffic stops.34 In addition, the ACLU’s New York branch has developed a Stop and Frisk Watch app, which allows New Yorkers to record abuses of New York’s controversial anti-firearm stop-and-frisk policy.35 After an app user records a stop and frisk, s/he is immediately sent a survey that allows ACLU officials to monitor patterns and assess for illegalities. Most interesting, the app automatically alerts other app users of the location of the stop and frisk, so that activists can crowdsource sousveillance and attempt to prevent the escalation of police brutality.

Yet as this book has taken pains to show, power and its abuses do not simply emanate from what Foucault called the “mythicized abstraction”36 of the state. Without the assistance of a diverse assortment of citizens and private institutions, liberal police power simply could not thrive. So by advocating sousveillance against cops and other state authorities, I risk sending an ambivalent message about power, its transmission, and its resistance. Despite this ambivalence, our current stage of surveillance culture begs for a line in the sand. While acknowledging the multipolarity of power, we should recognize above all that our seeing/saying bodies are cultivated to bring continuity and social cohesion to the present political order. A top priority of concerned citizens, activists, and critical scholars, then, should be disrupting that process, which means rejecting suspicion and overlooking our peers’ petty infractions in favor of turning our collective vigilance toward the more fundamental and far-reaching abuses of the agents of state power.

* * *

All of these suggestions, in one way or another, urge us to avoid getting pulled into lateral surveillance efforts. When we are pushed to become the “eyes and ears” of the security apparatus or the local police department, we can resist by rejecting those demands on our sight and speech—by refusing to look at our neighbors with suspicion, by sidestepping the state’s colonization of our social responsibility, and by turning our eyes toward reckless and abusive figures of authority. Yet trends in security politics and digital culture suggest that in the coming years we will be increasingly expected to police one another using the communication and surveillance technologies we have on hand. As Copwatch helps demonstrate, there is liberatory potential inherent in this “empowerment.” But to truly embrace the political potential of that empowerment, we have to avoid buying into the climate of pervasive suspicion to which the “If You See Something, Say Something” campaign and its corollaries contribute. Instead, we need to learn to look the other way. Ultimately, citizen-policing initiatives—no matter how well-intentioned—simply gloss over the U.S.’s myriad structural maladies (such as neoliberal economic policies and unbridled military interventionism) that ensure the reproduction of crime and fan the flames of terrorist rage. Thus in a very important sense, the impulse to police our peers threatens to be more depoliticizing and socially destructive than the merely symptomatic threats of crime, petty immorality, and terrorism. The problem is not that we don’t live in a radically homogenized social order free of moral and criminal transgressions, it’s that we are being mobilized against one another in endless battles for more security, more safety, more comfort, and more moral conformity.

Yet in order to thrive, these citizen-policing projects demand our consent.37 As Barbara Cruikshank reminds us, “citizens must be made—which says to me that citizens can be remade, and that the social construction of citizenship is both a promise and a constraint upon the will to empower.”38 Keeping this promise in mind, we can use our eyes and mouths to learn from others, remake ourselves, and build creative new forms of community and solidarity. If any cause is worth going vigilant for, surely that is it.