66 Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Fall of the Rebel Angels, 1562, oil on panel. IRPA-KIK, Brussels

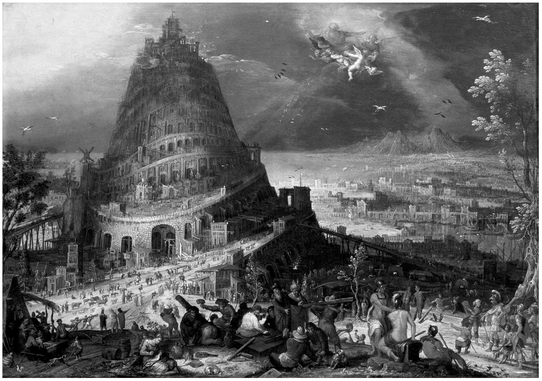

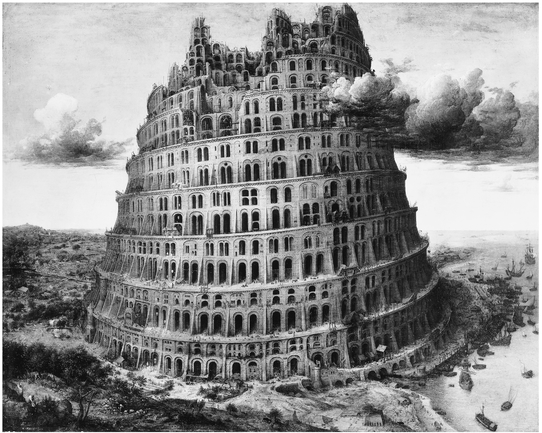

The years 1562-63 marked a major change in Bruegel's creative process. Original and complex allegories virtually disappeared, and it was not until his Misanthrope and Magpie on the Gallows, painted in 1568, the year before his death, that Bruegel created another painting as unprecedented as Children's Games, Carnival and Lent, the Dulle Griet, and The Triumph of Death. Instead, he shifted to traditional Biblical subjects that could be readily identified — his Fall of the Rebel Angels and Suicide of Saul of 1562, the Flight into Egypt and Tower of Babel of 1563. Even after this date most of his subjects could be accommodated within a familiar category such as the seasons, proverbs, peasant satires, or a Biblical story. Bruegel's presentation of subjects such as his Peasant Dance and Peasant Wedding may be novel, but they belonged to a category with which his viewers were already familiar. They did not need to stop and consider what the painting was about. In view of the success that Bruegel seems to have achieved with his innovative paintings and prints this is an intriguing turn of events. Although it receives less attention than the reorientation in subject-matter that occurred in 1556 with Bruegel's shift from landscape to Boschian satires, it is equally remarkable.

Personal as well as professional considerations may have had a role in this transition. It occurred around the time of his marriage to Mayken Coecke, daughter of Pieter Coecke van Aelst, in 1563 and his move from Antwerp to Brussels, timing that suggests that the two events may have been related.1 Perhaps Bruegel's new obligations prompted a more cautious strategy in terms of both his financial situation—traditional subjects could be marketed to a wider segment of the buying public —and his vulnerable status as a second Hieronymus Bosch, a reputation that carried with it the suspicion that he shared Bosch's irreverent attitude toward the heads of church and state. When Bosch painted the Haywain and included kings, clergy, and the Pope among the greedy sinners destined for hell, it was in a different, less explosive environment. By Bruegel's time any sign of criticism or dissent could engender a harsh and repressive response. Brussels was the seat of the government and hence by no means a safe haven, but by moving to the city Bruegel could distance himself from Antwerp with its reputation as a center for disruptive religious dissidents. At the same time a shift away from original allegory and in favor of clearly identifiable subjects was an effective way to defuse suspicion. "Things are at a turning point" ("res est in cardine") was proverbial;2 by 1562 Bruegel had reached a turning point, a critical juncture in his career, and with escalating violence in the city of Antwerp even one's physical safety was in jeopardy. The imperial edicts had heightened the hunt for heretics, spies were a constant threat, and suspects were being tortured, burned in public, and drowned in secret, and with suspicion and aggression so widespread it was increasingly difficult to avoid trouble with the authorities. Original allegories such as Carnival and Lent, the Dulle Grid, and The Triumph of Death, as well as the irony in some of Bruegel's prints, left the artist open to the charge that he had satirized religious rituals as empty and the actions of the government as cruel, repressive, and ineffective. If Bruegel was not actually in trouble with the authorities by the time he completed The Triumph of Death he might have feared that such an attack would occur.

The experience of the printer Christopher Plantin in the years 1562-63 indicates the magnitude of the difficulties faced by those living in Antwerp at this time, the efforts required to avoid suspicion and prosecution, and the degree to which people were disposed to conceal and dissemble their beliefs.3 The 1550 edict of Charles V held a master printer responsible if any workman in his establishment printed heretical materials. In 1561 Plantin fled the city under suspicious circumstances just as his print shop was about to be searched for compromising documents on orders from Margaret of Parma, regent for Philip II. An informant was clearly responsible for this intrusion. The instructions sent to the Margrave of Antwerp, Jan van Immerzeels, stated that the government had received a book printed in Plantin's shop that "contravened the enactments and public edicts of our sovereign lord the King," and that "whereas he who sent us this book has also warned us that the said Plantin and those about him are tainted with the heresies of the new religious, with the exception of a corrector and a servant," the margrave was ordered to confront Plantin and search the premises.4

The affair was complicated, and it is difficult to determine Plantin's own role in it and the part played by others. Although it is certain that an informer precipitated the action against him, it is also clear that others in sympathy with the printer warned him of the impending search and gave him time to escape. Jan van Immerzeele, the local authority charged with hunting down heretics and pursuing the charge against Plantin, was less than zealous in carrying out his duties, the reason becoming clear a few years later when it was found that at the time of the threat to the printer he was secretly a Calvinist. To complicate the matter further, a bankruptcy was arranged by Plantin's friends so that they could buy all his presses and stock and prevent them from being confiscated by the government; the goods were later returned to the printer. Although Plantin was exonerated on this occasion, he was again in trouble in 1563 for printing another book, and again the charges were dismissed. However, Plantin was by no means innocent, as it seems certain that during the same period he had, in fact, printed heretical books including the Spiegel der Gherechticheit (Mirror of Righteousness) of Henrik Niclaes, leader of the movement known as the "Huis der Liefde" (Family of Love).5

Even if a person was guilty of nothing more than a Catholic reformist position it could jeopardize their safety. Plantin was not the only person with an entry in Abraham Ortelius's Album amicorum who was in trouble with the authorities. Furio y Ceriol, a Spaniard living in the Low Countries, was imprisoned for writing his Bononia sive de libris sacris in vernaculam linguam (1556), a defense of vernacular translations of the Bible indebted to Erasmus's Paraclesis.6 Arrested for heresy in 1560 by the Rector of the University of Louvain on the orders of Philip II, Ceriol was released from prison but not acquitted, was rearrested, and then, after escaping from prison, was kept under constant surveillance between 1561 and 1564. Only his threat to write books against the authorities in French, Latin, and Italian prevented his return to prison.7 In 1561 Abraham Ortelius felt it necessary to enquire which illustrations on maps and books were suspect in order to avoid trouble with the authorities.8 By 1562-63 the situation had become even more dangerous.

Whether or not Bruegel was guilty of any indiscretion, there was always the risk that he would be caught up in the frenzy of accusations and suspected of heretical leanings. Under these tense conditions paintings with unprecedented subjects could prove hazardous. If a painting such as The Triumph of Death was hung in a private setting the danger was minimized, but not all viewers were trustworthy. At a time when many people were cautious about expressing their views and revealing their religious affiliations there was no assurance that every visitor would be favorably disposed toward the religious and political views of the host and his artist. As Plantin's experience indicates, spies were a danger in any setting, not just a threat to those who attended the religious conventicles. Whole neighborhoods could be suspect. Margaret of Parma's "secret agent" referred to the neighborhood of the Old and New Bourse and the Doornikstraat as "hotbeds of Calvinism."9 Religious conviction may have motivated some informants, but when the government gave monetary rewards for incriminating information any moderately prosperous household became susceptible to the malice of neighbors, or denunciation by avaricious servants or workmen. Even within families there could be dangerous differences of opinion. "Adrian the Painter ... betrayed by the zeal of his own Father" was strangled and burned at the stake on January 19 1559.10

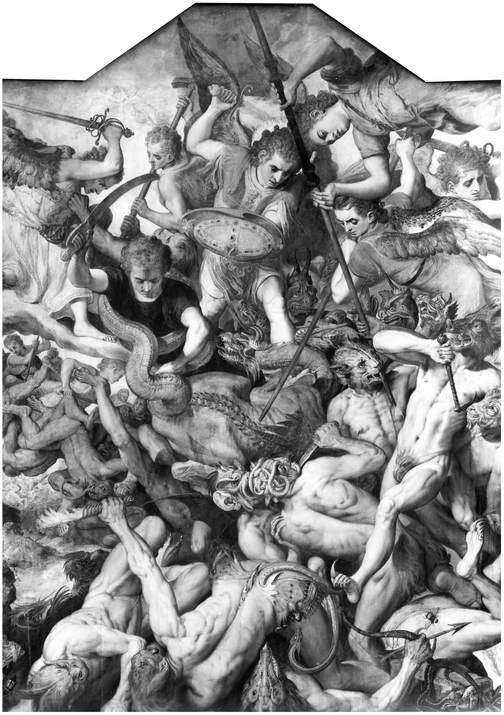

Bruegel's substitution of traditional subjects for original allegories helped safeguard both his life and his livelihood, but many of the fundamentals of his art remained unchanged. Even as he made this accommodation to the dangers of the time satire did not vanish from his art with respect to its principles, traditions, or customary targets. The Fall of the Rebel Angels (Figure 66) carries his signature and the date, "M.D. LXII BRUEGEL," in the humanist style, and while the Biblical subject made it difficult to see the painting as criticism of church or state it did not prevent Bruegel from attacking another, more personal problem, one that was central to his own concerns. Parody is a traditional stratagem in satire, and tor those familiar with The Fall of the Rebel Angels painted by Frans Floris in 1554 (Figure 67), Bruegel's version of the subject could be viewed as a witty critique of a famous painting by his most prestigious competitor. In 1562 Floris was the most prominent artist in the Low Countries. A Romanist and a follower of Italian stylistic models, Floris created the kind of art that received the most attention and commanded the highest prices. It perpetuated the heroic and mythic traditions of ancient Greece and Rome, imitating the styles of Italian artists such as Michelangelo and Raphael, who emphasized the nude, muscular body, classical architecture, and measured, perspectival space. Bruegel was creating a different kind of art, following Horace's "prosaic Muse" or, as Martial expressed it, a "parva Musa" (a poor little Muse).11 It was a "minor style of painting" according to Pliny's categorization,12 not as fashionable as the Italianate art that was in favor, but equally ancient and venerable.

Two paintings, both dated 1561, illustrate their differences. Frans Floris's mythological painting Banquet of the Sea Gods has a subject taken from Ovid's Metamorphoses with its description of the gods taking their ease in a "palace carved out of lava rock" and decorated with purple shells, being waited on by naked nymphs, and "drinking rare drinks in cups of jade and crystal" (see Figure 3, p. 18).13 Bruegel's Dulle Griet, done in the same year, draws on the literature of the ancient world to create an allegory of madness and folly. Instead of parading his sources or slavishly following them, Bruegel used them as an integral part of his conception.14 Floris includes large, idealized nudes painted in the Italian manner. The sensual nude is absent in Bruegel's art. The naked are sinners in the Dulle Griet and in his drawing for Luxuria (Lust), or they appear in a traditional religious context—the wise and foolish virgins standing at the gates of heaven, or the dead rising from their graves at the Last Judgment. Floris created paintings that exploited the often mindless enthusiasm for things Italian. Bruegel produced art in an alternative tradition, one that was equally a Renaissance phenomenon but owed its genesis to a northern artist, Hieronymus Bosch.

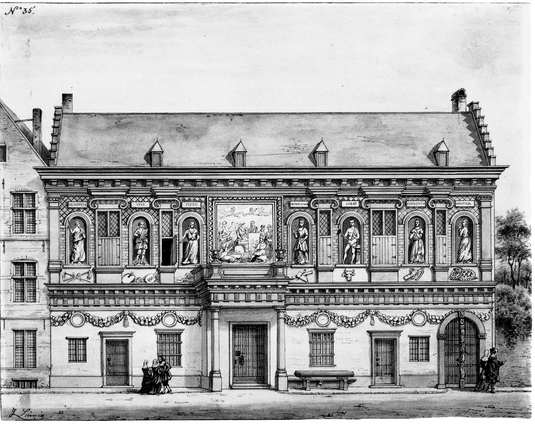

By 1562 Bruegel had achieved considerable success, but it did not compare with that of Frans Floris. Floris's financial and artistic success was at a high point, made visible with his new and magnificent house built after the Italianate design of his brother Corneille Floris (Figure 68). Located in a recently opened quarter of the city, it was one of the most impressive houses in Antwerp, with stone pillars carved in the classical style and Floris's artistic views prominently on display in its decoration. The seven paintings decorating the facade were illusionistic imitations of bronze sculptures representing the qualities that a great artist needed, including personifications of Skill, Diligence, and Knowledge of Poetry, and a painting of Pictura was placed over the doorway.15 Floris was a major force in the cultural life of the city: he was the artist chosen to supervise the elaborate, classically inspired decorations for the Landjuweel, the splendid rhetorical competition held at Antwerp in 1561. Bruegel had yet to receive a commission from the luminaries of church or state.

66 Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Fall of the Rebel Angels, 1562, oil on panel. IRPA-KIK, Brussels

67 Frans Floris, The Fall of the Rebel Angels, 1554. Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten, Antwerp. KMSKA photo copyright Lukas-art in Flanders vzw

68 Façade of the house of Frans Floris, constructed 1562. Museum Plantin-Moretus/Prentenkabinet, Antwerpen—UNESCO World Heritage

The commission to paint the newly constructed canal between Brussels and Antwerp was not received until the end of his life, and he left the work unfinished at his death in 1569. Floris's art had made him wealthy: at one point he had an income of 1,000 florins a year, seven times that of a masons16—somewhat less than the annual cost of William of Orange's falcons but a large sum for a painter—and he employed a shopful of assistants.17 In 1562 Bruegel was still working alone, with no sign of workshop participation. Floris was patronized by the most important people in the country, and the visitors to his studio included such notables as the Prince of Orange and the Counts Egmont and Horn; Van Mander would later blame the artist's association with the Flemish nobles for his artist's drinking habits and enjoyment of lavish living.18 Bruegel's patrons were drawn from a less elevated social class whose resources and lineage did not place them in the upper ranks of society. Floris produced paintings suitable for a great churches and palatial settings, while Bruegel's were appropriate for more intimate domestic spaces and closer viewing. The luxurious feast is a favorite subject for Floris. Moderation is a recurring theme in Bruegel's art, and he satirizes drunkenness and prodigality. The poem that Dirck Volckertsz Coornhert sent to Frans Floris is probably typical of the reaction of the men in Bruegel's circle who admired Floris's art, but faulted his dissipated life. In it Coornhert relates a dream in which Dürer appeared to him, praising Floris as a painter but reproving his bacchic habits.19

The fame of Frans Floris relative to Bruegel's more modest reputation is well documented, and this supremacy continued throughout Bruegel's lifetime and into the following century. In his Description of the Low Countries, written in 1567 Guicciardini, began his section on living painters with Frans Floris, describing him as a painter so excellent in his profession that he was second to none, a "great inventor" who had the honor of bringing from Italy the mastery of depicting muscles and representing the skin of men in a most natural way. Bruegel receives a brief mention after several other artists and is identified simply as an "imitator of the science and fantasy of Hieronymus Bosch" who has earned the name "a second Bosch."20 Niclaes Jonghelinck, the rich merchant and tax collector, owned 22 paintings by Frans Floris and 16 by Bruegel; when they were pledged as surety to the city of Antwerp in 1566 Jonghelinck was careful to identify the subjects of all his paintings by Floris but only three of Bruegel's, and while this document may not reveal Jonghelinck's personal evaluation of them it probably reflects their market value. Writing the first history of northern art in 1604, Van Mander devoted nine pages to Floris, and less than three to Bruegel. Floris is described as the "glory of painting in the Netherlands," the Flemish "Raphael Urbino," and an artist always busy with "large, fine altar paintings and other big pieces" that were "exhibited splendidly in places where everyone could see them." Referring to Floris's The Fall of the Rebel Angels in the Onse Vrouwe Kerck (Church of our Lady) in Antwerp, Van Mander described it as his most remarkable work, a

wonderfully artistic composition ... painted so well that all artists and connoisseurs are astounded. The picture displays a weird mingling and falling of male bodies of various demons, and is an excellent study of the anatomy of muscles and tendons. The dragon with the seven heads is very venomous and terrible to behold ...21

There is no reason to assume that the reception of Floris's The Fall of the Rebel Angels was any less enthusiastic when it was first unveiled in 1554. It is equally certain that Bruegel was aware of the artistic issues at stake when he created his own version of the subject eight years later. It is a carefully calculated display of his own abilities and artistic agenda, a counter to the prevailing fashion for Italianate art. In this, his last major foray into fantastic Boschian territory, Bruegel paid homage to Bosch as one of the great innovators in Renaissance art, the pioneer whose imaginative satires such as the Haywain deserved as much recognition and acclaim as the art of the Italian masters such as Michelangelo and Raphael. Instead of presenting the fallen angels as muscular male nudes, Bruegel transforms them into inventive Boschian grylloi. Bruegel paints the deformity of sin. Floris's fallen angels retain their sensual appeal. Floris was admired for his ability to make cloth and fur appear tactile and convincing. Bruegel paints delicate insect wings, mussel shells, wasps, hairy creatures, some figures composed of exotic vegetation and others that are egg-like, a myriad of details minutely rendered and dependent for their realistic effect on close observation of natural phenomenon. In a particularly pointed contrast, Bruegel placed butterfly wings on one of his Boschian figures located near the center of his painting, a clever parody of the butterfly wings that sprout from the buttocks of the male nude in the center of Floris's The Fall of the Rebel Angels (Figure 69).

There is no record of Floris's own response, but a poem written by Lucas d'Heere, an artist trained in Floris's workshop, suggests that it did not go unnoticed. D'Heere's "Invective against a Certain Painter who Criticized the Painters of Antwerp" was published in 1565 shortly after Bruegel's painting was completed, and it is a defense of "richly adorned paintings," with the poet taking a critical view of paintings depicting "kaeremes poppen" (carnival dolls).22 As David Freedberg has demonstrated in his analysis of the poem, even if Bruegel was not the "certain painter" being attacked, the existence of the poem makes it clear that an interest in "art theoretical problems and categories" was not restricted to Italy and that differing views were being debated with some acrimony.23 If there was no northern Vasari to give it literary expression it was present nonetheless and affected what was created and how it was received. The conflict was not between the "classical" and the "popular." Bruegel and Floris were both indebted to the interest in the ancient world that had become a significant aspect of northern culture by the middle of the sixteenth century. The two artists differed in their relation to the classical past, how they accessed it, what they valued, and the use they made of it. Floris depended on Italian stylistic intermediaries to set the standard and utilized that part of the ancient literary inheritance epitomized by the mythological tales of Ovid. Bruegel followed an independent route, taking from the classical past what was useful for his own purposes and meeting the standards for art articulated in ancient literature, an achievement that Ortelius recognized when he praised the artist.

If Bruegel's The Fall of the Rebel Angels was perceived as a satire, an attack on the Romanist art of Floris and his followers, it was certain to arouse animosity. The retaliation of artists who felt that their work was being maligned might cause the artist discomfort, and might perhaps even blight his prospects with some potential patrons, but it was unlikely to lead to a life-threatening encounter with the authorities. On the other hand, the fallen angels were not the most innocuous of Biblical subjects, given the religious and political climate. Subtle details suggest that even here artistic issues were not Bruegel's sole concern. In the Bible the rebel angels are the heretics par excellence (Revelation 12:7-13), arrogant usurpers punished for their pride and ambition. In Bruegel's The Fall of the Rebel Angels some of the fallen angels wear helmets. Golden crowns adorn the heads of three of the horned animals, and in the lower right corner another crown is placed on the head of a female with wild hair who looks as crazed as Bruegel's figure of Madness in the Dulle Griet (Figure 70). In 1562 helmets and crowns were signs of high status, worn by people in positions of power. Used as headgear for the fallen angels they would suggest that the powerful were using their position to persecute others when they were themselves the true heretics.

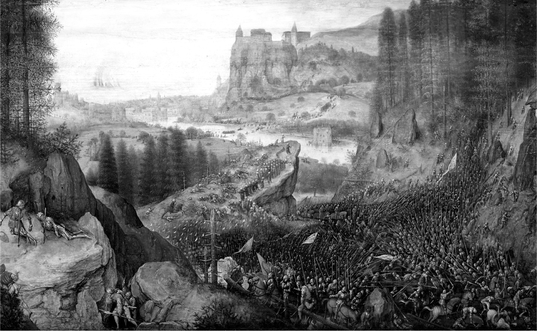

A second painting, the Suicide of Saul, done in the same year as The Fall of the Rebel Angels, is signed "BRUEGEL. M.CCCCC. LXII," and while it differs from Bruegel's other surviving works to such a marked degree that the attribution might seem questionable, the date and signature appear genuine, being in Roman square capitals like those of other paintings done after 1558 (Figure 71).24 Size and subject also suggest that the painting was part of Bruegel's effort to broaden his clientele. Because it is smaller than The Fall of the Rebel Angels, measuring only 33.5 × 55 cm., it could be undertaken without a commission. The choice of a Biblical subject also made it relatively safe, although it was not entirely innocent given the political and religious tensions. Like The Fall of the Rebel Angels, the Suicide of Saul refers to God's punishment for the sin of pride.

71 Bruegel the Elder, Suicide of Saul, 1562, oil on panel. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien

The Suicide of Saul also gave Bruegel the opportunity to showcase his abilities both as a miniaturist and as a landscape specialist. Great armies are crowded within the confines of a limited space, with a dramatic mountainous landscape visible in the far distance. In his The Triumph of Death Bruegel drew attention to his wide-ranging knowledge with visual references to the work of other artists, and the Suicide of Saul may have been similarly motivated, conceived as a tour de force that would broaden his appeal and engage the interest of discriminating connoisseurs. As Marijnissen and Grossmann have noted, the painting has affinities with Albrecht Aldorfer's Battle of Issus and Alexander with its panoply of warring armies.25 Aldorfer's famous work was painted earlier in the century, perhaps as a response to Pliny's description of a famous painting "containing a battle between Alexander and Darius" that was so well done, according to Pliny, that it achieved "the highest rank" among the ancients.26 There is a similar confrontation between two great armies In the Suicide of Saul, and while the battle between the Israelites and the Philistines in 1 Samuel 131 is Biblical rather than classical the effect is the same. It allowed Bruegel to cultivate an audience with more sophisticated tastes while still avoiding the dangers posed by an original subject that could be misunderstood. The Suicide of Saul is not an anomaly. The use of a recognizable subject that recalls another famous work of art is consistent with other changes taking place in Bruegel's creative process.

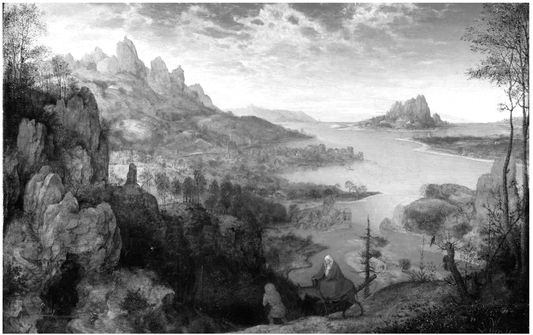

In the following year Bruegel created a second small painting, his Flight into Egypt, signed "BRVEGEL" and dated "MDLXIII" (Figure 72). Again, the subject is Biblical and can be readily identified. In the subtlety of its coloration the Flight into Egypt is similar to the Suicide of Saul of the previous year, but there are only three figures, Joseph, Mary, and the child Jesus in Mary's arms, and the landscape dominates the composition. Bruegel had treated the flight into Egypt before. In one of his early landscape drawings the holy group is seated on a high vantage point overlooking a broad landscape,27 and in a print from the series of the Large Landscapes, the holy family is shown at rest, the inscription reading "FUGA DEIPARAE IN AEGYPTUM."28 Bruegel's Flight into Egypt returns to the genre in which he first impressed connoisseurs and can be seen as a bid for their attention with a subject that allowed him to display his ability to compete with nature. Cardinal Granvelle was an "avid collector and serious connoisseur of art and architecture,"29 and if the Flight into Egypt listed in the 1607 inventory of his estate is identifiable with Bruegel's painting his effort met with success.30 Although increasingly reviled as a political and religious leader, Granvelle was not dismissed from his post and forced to leave the Low Countries until the following year, and when Bruegel painted his Flight into Egypt in the cardinal was still in residence, spending lavishly and busy with the construction and decoration of his Renaissance palace in Brussels.

72 Bruegel the Elder, Flight into Egypt, 1563, oil on panel. The Samuel Courtauld Trust, Courtauld Institute of Art Gallery, London

Even if the cardinal owned Bruegel's Flight into Egypt, the Biblical subject was safe and would not attract the attention of the authorities, although this does not ensure that the painting was devoid of any satiric associations. Describing events in Antwerp in 1561, Brandt wrote:

When any Trouble or Persecution was hatching against such of the inhabitants as were suspected of Lutheranism by the Magistrates, notice was privately given them of it by a certain Watch-word, which passing from one to another, was presently spread among the whole Party; such for instance was the following Scripture sentence: Joseph took the Mother and Child, and fled into Egypt. As soon as this signal came to the ears of those that had quitted the Romish Church, they either hid themselves, or, if the Gates were not shut, made the best of their way out of Town.31

Perhaps Bruegel was unaware of the Protestant password, but the painting differs from his previous treatment of the subject. There is no falling idol in the earlier works, and idolatry was a critical issue in the religious struggles, the source of many of the tensions that led to the Iconoclasm of 1566. Instead of depicting a peaceful scene with the holy family at rest, Bruegel shows the family in full flight. These changes could have been prompted simply by a desire to position the viewer "in medias res" and add a dynamic element to the painting, but whatever Bruegel's intentions, if his Flight into Egypt was in the possession of Cardinal Granvelle, who supported the Spanish policy of prosecuting heresy—the Edict of 1550 was reissuedhis recommendation32—it was as ironic as Granvelle's ownership of Dürer's Martyrdom of the Ten Thousand.

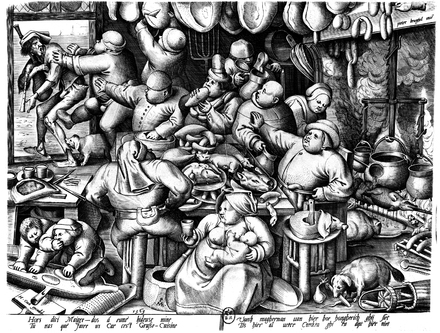

In such troubled times some caution was required, but even as Bruegel shifted to well-known subjects for his paintings Hieronymus Cock published two prints after Bruegel in which the subject is original and the satire harsh—the Thin Kitchen (Figure 73) and the Fat Kitchen (Figure 74), both dated 1563. No drawings survive for this unprecedented pair, and it is possible that they were done earlier, because the artist's name is spelled with an h in script and there are affinities with Bruegel's Alchemist of 1558. The child with a kettle on his head in the foreground of the Thin Kitchen is similar to a detail in the earlier print, and the two works share the same satirical point of view and attack similar problems: greed instead of moderation, laziness, and a desire to get something for nothing.33 Corpulence reigns in the rich kitchen. Everything is overfed and outsized, from the huge breasts of the woman feeding the fat baby in the foreground to the fat dog who continues to stuff himself and the obese host who pushes the thin man out the door. The thin kitchen fares little better with its scraggly, unkempt inhabitants, a bagpipe hung on the wall, and skinny hands grabbing greedily for the mussels in the bowl on the table, the food that was "cheap enough for poor folk's kitchens" as Ausonius wrote.34

The satire in Thin Kitchen and Fat Kitchen is scathing in its condemnation of the selfish rich and the shiftless poor, but the prints could be presented publicly without endangering the publisher or raising questions about the religious affiliations or political views of the artist. Neither print violates a governmental edict or makes an obvious reference to any divisive religious issue. Instead, the two prints are concerned with serious social problems that engaged the attention of many people in the Low Countries, the increase in the urban poor as peasants migrated from country to city, the growth of an urban-based middle class anxious to reconcile their monetary ambitions with their Christian obligations, and the ongoing dialog over responsibility to the needy

73 Bruegel the Elder, Thin Kitchen, 1563, engraving. Private collection, St. Louis

74 Bruegel the Elder, Fat Kitchen, 1563, engraving. Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

members of the community concerning who should do the giving and who was qualified to be a recipient. Large numbers of urban poor were a relatively new phenomenon in northern cities, and there was little recognition that they could be victims of economic forces beyond their control. Those who lived in squalor tended to be seen as lazy and to be held responsible for their poverty and the poor were feared by the more fortunate as a disruptive faction prone to violence and rebellion. In Antwerp and throughout the Low Countries this fear was exacerbated because the radical Anabaptists drew their support principally from the ranks of the "kleyne luyden" (small people),35 and unlike the Reformed Protestants (Calvinists and Lutherans), the sect did not share the values of the burghers, refusing, for example, to bear arms in the town militias.36

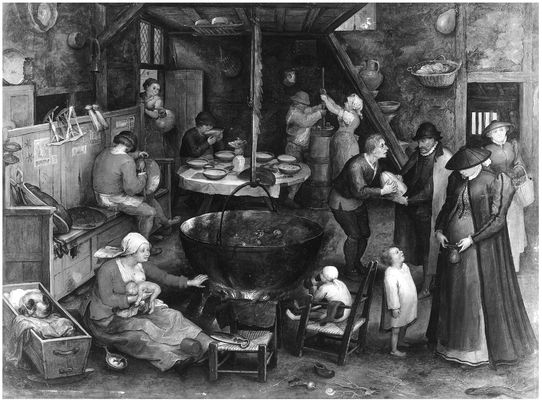

Bruegel's Visit to the Farm, a lost painting known from numerous copies, makes a revealing contrast with Thin Kitchen and Fat Kitchen (Figure 75).37 Satire has no place in the little painting. The bagpipe, with its connotations of sexuality and raucous holiday celebrations, is absent. Instead, a religious print is attached to the back of the bench, various tools are visible, and the peasants are hard at work, with two people churning butter and the man on the bench mending a pot. There are implements for spinning, and shears are on the chair in front of the fire, which has a piece of leather hung over its back in order to soften it and make it workable; full bowls of food are on the table and shoes and adequate clothing on all the adults, ample evidence that these are pious, hard-working people with moderate habits who deserve the assistance they are about to receive. Two well-dressed burghers have brought gifts, and the peasant bends in gratitude as he receives them. The donors are not giving to beggars on the street, as in Carnival and Lent, or responding to a poor man knocking at their door. Instead, they have chosen the recipients of their charity, sharing their wealth with those who work hard rather than with people like those in the Thin Kitchen where there is no sign of industry or good sense.

Satirists, especially those of a Horatian disposition, favor a middle way between extremes, adopting the spectator stance that encourages a thoughtful response. In Bruegel's Fat Kitchen and Thin Kitchen the extremes are criticized: people whose poverty is caused by their own greed and laziness as well as the prosperous whose only interest is in stuffing themselves. The contrasting scene in the doorway of each print, with the thin man welcoming the fat man while the fat man kicks thin man out, moderates the onus on the poor by emphasizing the violent and unchristian behavior of the wealthy. However, the poor are not exonerated. Begging from door to door was condemned by reformers. In De rerum inventoribus Polydore Vergil states, "Although we attribute to Christ love for poverty, which results in spiritual advantages and purity, let us not ascribe to him squalor and extreme poverty ... He did not beg for food from door to door."38 For the emerging middle class, rural peasants at work made a useful contribution to society, unlike the poor in Bruegel's Thin Kitchen who are idle and troublesome, knocking at the door of the rich and trying to live off the largess of others.

75 After Bruegel the Elder, Visit to the Farm, oil on panel. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien

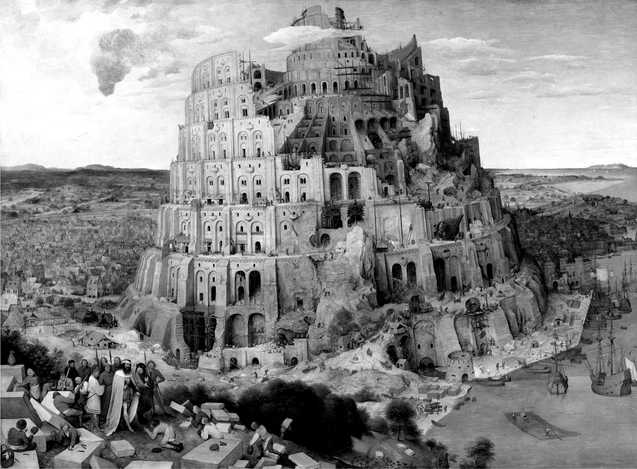

Bruegel's Tower of Babel, signed "BRVEGEL FE. MCCCCCLXIII," is the last painting closely connected with his years in Antwerp (Figure 76). Large and impressive, it was completed in the same year as the Flight into Egypt, and like the smaller painting it repeats a subject Bruegel had done before. A tower of Babel painted on ivory is credited to Bruegel in an inventory of the belongings of his Italian friend Giulio Clovio.39 Caution again prevails with the choice of a Biblical subject (Genesis 11:1-9), although it had the same negative connotations as his Fall of the Rebel Angels and Suicide of Saul as an example of God's punishment for pride. However, it differs in having classical as well as Biblical antecedents. The tower of Babel is found in Herodotus and in Flavius Josephus's Antiquities of the Jews, and both sources are included in Polydore Vergil's De inventoribus rerum:

When Nemroth (Nimrod) son of Ham, the son of Noah, undertook after the deluge to turn people who dreaded the power of the waters away from the fear of God, he meant that they should rest their hopes on their own strength, and he persuaded them to build a tower (described elsewhere in a suitable place) so lofty that the waters could not rise above it. Then, when they were already madly [insanientibus] involved in the work they had started, God divided language, so that they could not understand one another because their tongues were many and discordant. This, then, is the origin of the variety of the many languages that people use even now, according to Josephus in book I of the Antiquities.40

76 Bruegel the Elder, Tower of Babel, 1563, oil on panel. Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wien

Because Bruegel shows the tower under construction, the king in the foreground—the figure in royal attire visiting the site and receiving the obeisance of the workmen—could be identified with Nemroth (Nimrod).41

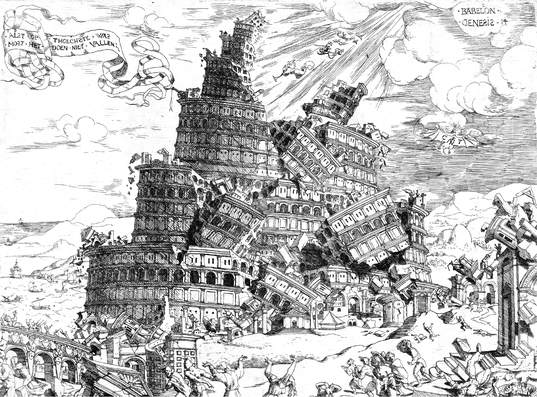

The tower of Babel was a well-known subject, but an unusual choice for a painting of this size.42 It was illustrated earlier in manuscripts, including Giulio Clovio's version in the Farnese Book of Hours, a work Bruegel probably knew from his sojourn in Italy and contacts with Clovio, but large-scale paintings of the subject are rare prior to 1563 and none are dated. One example in Venice is attributed to the circle of Jan van Scorel,43 and two are known only from documents. A "torre de Babilonia" by Hieronymus Bosch is listed in an 1548 inventory of the possessions of the wife of Hendrik III of Nassau, and a painting attributed to Patinier was seen in the house of Cardinal Grimani in 152144 These references to Bosch and Patinier suggest that the subject was favored by artists renowned for their "landscapes." The tower of Babel appeared more frequently in drawings and prints, such as Hans Holbein the Younger's woodcut in the Historiarum veteris testamenti icones published at Lyons in 1538, and a drawing by Jan van Scorel dated 1540.45 The etching by Cornelis Anthonisz is closer in time to Bruegel's painting, but presented differently (Figure 77). Here the tower is collapsing dramatically, blown apart by a heavenly wind, with one inscription reading "Babelon/Genesis," and the other "When it was highest / must it not then fall?"46 There is no destruction in Bruegel's conception. Instead, the viewer is again "in medias res" with the tower under construction. The outcome was well known from the Biblical account, in which the proud builders scattered and their ambitious tower was left unfinished as God's punishment for their pride and arrogance, but Bruegel does not show the Biblical ending or follow Anthonisz in portraying a dramatic and violent demise.

Perhaps the subject was chosen by the patron and Bruegel was simply following instructions, but whatever the circumstances, he used the painting as an opportunity to display his particular strengths. If Bruegel could not compete with Frans Floris in the creation of anatomically convincing nudes he had no equal in close observation, evocative landscapes, and the ability to record the various activities of life around him in a convincing way. By showing the tower under construction, locating it in a seaport, and surrounding it with a landscape seen from a high viewpoint and receding dramatically, Bruegel could capitalize on these abilities, creating a beautiful landscape and presenting the kind of technical subjects that engaged his attention on other occasions. The ships on the waterfront are depicted with the same accuracy as in Bruegel's series of prints published by Hieronymus Cock around 1561-62.47

Even though Bruegel's Tower of Babel avoids original satire with all its attendant dangers, the traditions of the genre continue to inform his art. As inherited from the ancient world, satire was the genre appropriate for recording the details of daily life. Robert Estienne emphasized this aspect in his Thesaurus latinae linguae published in 1531: "Satyra ... appears to be said like satura ... and it received this name as a genre because it seems to be filled to satiety with people and facts."48 Renaissance literary satires follow their ancient models by including practical information, such as Rabelais's discussion of a humanist education (Gargantua, 21-4), which is recommended by Gilbert Highet as "an essential document for anyone who wishes to study the re-emergence of classical ideas in the Renaissance,"49 or Ulrich von Hutten's ironic satire Inspicientes, which as Thomas Best observes "quickly becomes a lesson in German customs."50 In the Tower of Babel Bruegel presented his viewers with a detailed, comprehensive record of contemporary buildings and construction practices. Antwerp was in the midst of a building boom that produced the new town hall, built between 1561 and 1565, and the development of the New City with its many expensive houses. Guiccardini wrote that the buildings in the New City were faced with beautiful white stones and that its many canals could accommodate 100 big boats.51 Bruegel was witness to all this building activity, and the Tower of Babel is encyclopedic in its rendering of construction practices and lifting devices, including a crane like the one on the wharf at Antwerp in which men labored inside a treadmill to provide the power for lifting heavy loads.52

77 Cornelis Anthonisz, The Fall of the Tower of Babel, etching. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Bruegel's unique treatment of the tower of Babel suggests a deliberate effort to advance his own artistic agenda, broaden his appeal, and advertise his special strengths and expertise. As a record of sixteenth-century technology Bruegel's Tower of Babel is an impressive achievement, an effective strategy for holding the interest of viewers and satisfying the Horatian principle that successful art should include something for everyone, the ordinary viewer as well as the discriminating connoisseur. Compared with later versions of the subject, such as Hendrick van Cleve's Tower of Babel (Figure 78),53 with its comparatively amorphous tower and heavenly scene with God and angels in the sky (the image of God clearly adapted from Michelangelo's Sistine ceiling), Bruegel's painting makes a persuasive case for his own perspective on artistic matters. The antique is paraded in van Cleve's painting, while Bruegel follows the traditions of satire, with its rejection of the mythic in favor of the close observation of the world around the artist.

The Tower of Babel did not jeopardize Bruegel's physical safety. There was no danger in displaying this Biblical subject publicly. The paintings on the pageant cart that signified "Presumption" in the Antwerp Ommegang of 1561 included a Tower of Babel as well as a Fall of the Giants.54 However, as a symbol of human arrogance, a site singled out as a dramatic example of human hubris and its punishment, the tower could be applied to contemporary conditions. In his Ship of Fools Sebastian Brant used the tower of Babel as an example of foolish building, satirizing the pride and lack of foresight of those who do not calculate the cost of a project and their ability to pay beforehand and are forced to leave the work unfinished.55 Accusations of extravagance and hubris were being made on both sides of the deepening political and religious divide. In 1559 Cardinal Granvelle described the Netherlands as "too prosperous," stating that "the people were not able to resist luxury and gave in to every vice, exceeding the proper limits of their stations." He accused the nobles of living beyond their means, borrowing money from the merchants and sinking into debt in their effort to live like kings while the merchants made "unnecessary expenditures" as they tried to "equal and surpass the nobles."56 The building boom in Antwerp was an obvious target for this criticism, with Frans Floris's expensive new house just one manifestation of these ostentatious efforts at upward mobility.

In turn, there was widespread resentment over the lavish expenditures of the court and the continual pressure to supply the government with money. Cardinal Granvelle was roundly criticized for his own profligate lifestyle and for a greed so insatiable that he was rebuked for his avarice by Charles V in 1552.57 In 1563, at the time when Bruegel painted his Tower of Babel, Granvelle was engaged in his own expensive building projects. Extensive work was being done at "La Fontaine," his great country house just outside the gates of Brussels, and fortifications were being added to his chateau "Cantecroix" at Mortsel. An even more grandiose project, his "Palais Granvelle," was begun at Brussels in 1561 with the design of its facade indebted to the Farnese palace in Rome, an early example of Italian influence on architecture in the Low Countries.58 As the extreme example of grandiose ambition, the tower of Babel could be viewed as a reference to the excess and immoderation visible on all sides.

78 Hendrick van Cleve, Tower of Babel, oil on panel, 53 × 75 cm. Stockholm University

Bruegel's Tower of Babel was also relevant to the religious and political animosities engulfing the Low Countries. Those critical of the new reformist sects used the tower to describe their cacophony of conflicting views. Marc Van Vaernewyck, a contemporary witness, referred to three different doctrines, "Calvinists, Martinists, and Anabaptists," and asked, "Is it not a new tower of Babel, where God threw languages into confusion ... the builders of Babel could not understand each other like the sectaries today ... heresy is a monster with many heads."59 During the years when Bruegel worked in Antwerp the city had a reputation as a gathering place for these religious dissidents. Writing from Antwerp in July of 1562, the English agent Richard Clough reported on the troubles in the city: "For, at this instant, I can write you of nothing certain; but every man speakes according to his religione."60 Writing again in January 1563, at the time when Bruegel was painting the Tower of Babel, Clough stated, "ytts ys moche to be douttyd of an Insourrecyon within the towne; and that, out of hands: for here ys syche mysery within thys towne, that the lyke hathe nott bene sene. Allmost everynyght, howsys [are] broken up and robbyd." Then, describing an incident the night before in which "there came about xvi or xx in a company to a corne-seller's howse ... and rane att hy dore" to break it down, with the householder responding by firing at the thieves,61 Clough concluded with the pessimistic assessment, "I do moche doutt of grett trowbells that maye chanse here; and that, out of hands."

Throughout this period in Netherlandish history Antwerp continued to be associated with Babylon in the minds of those opposed to the reform. Responding to the hedge-preaching that preceded the outbreak of Iconoclastic violence in 1566, a Catholic friar wrote:

See and hear, outside Antwerp, that great Babylon ... they all stand and preach and rant and gesticulate against each other. Here stands a cursed Calvinist or Sacramentarian, there stands a damned Lutheran or Martinist or Confessionist, there stands a cursed Anabaptist, there a devilish Libertine, each trying to outdo the others.62

After coming to the Low Countries to exterminate the heretics, the Duke of Alva described Antwerp in a letter written to Philip II as "a Babylon, confusion and receptacle of all sects indifferently and the town most frequented by pernicious people."63

There was little danger for the artist or his patron when the tower of Babel was so widely used by those critical of the new reformist sects. The painting could be viewed in a way congenial to a conservative Catholic position.64 On the other hand, a more subversive interpretation was possible. For the Reformed, Rome was Babel. In Bruegel's painting the huge edifice is being erected around a great outcropping of rock. This rocky area does not appear in other versions of the subject, and it is a particularly strange intrusion because it juts up from a relatively flat landscape rather than a mountainous, alpine setting where it would seem more appropriate. For those opposed to the Catholics in the religious controversies, the rock could refer to the Catholic Church and Matthew 16:18, "You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my church," the passage on which the papacy based its authority. Seen from this point of view the arches of the tower could recall the Colosseum in Rome, with Philip II, supporter of the papacy, acting like Nimrod, the impious builder in the Bible. Hubris would then reside with the king and the papacy, and the outcome of the Biblical story would predict their eventual downfall.65

Factions diametrically opposed in the religious debates could find support for their views in Bruegel's Tower of Babel, but the painting allowed for a third, less partisan interpretation. Considered from the perspective of Christian humanists such as Ortelius and Coornhert who favored an Erasmian "middle way" in the religious struggles of their time, the Tower of Babel could be seen as a condemnation of extremists on both sides, the Catholic traditionalists as well as the fanatical Reformed. By 1563 pride was evident on all sides, with Catholics persecuting the Reformed sects, which were at war with each other and persecuting those who differed from them. Like the Catholics, they were burning other Christians over questions of dogma. John Calvin was responsible for the death of Michael Servetus, burned at the stake at Geneva on October 23 1553 after he disagreed with Calvin on the descent into limbo and was convicted of heresy.66 Sebastian Castellio's De haereticis was written to protest the execution of Servetus, with Castellio gathering the views of other authors as well as making his own plea for toleration, and it includes Erasmus's argument that the persecution of heretics was both unchristian and counter-productive. Attacking the dogmatism of the Scholastics, Erasmus states, "Even more intolerable is it to construct new dogmas every day and rear them to heaven as sacred and immovable towers of Babel. For these we fight more fiercely than for the dogmas of Christ."67 In De lingua Erasmus expresses the same concern with the same image when he asks the pessimistic question—are we "repeating the destruction of the Tower of Babel"?68

For those who saw the religious controversies as arguments over nonessentials that did little to promote individual morality or the harmony and prosperity of the state, there was error on both sides. In a letter written in 1567 Abraham Ortelius included both "the Catholic malignancy" and "the Hugunot diarrhea" when he lamented the sad state of the Netherlands "menaced by so many diverse sicknesses,"69 and symptoms of extremism and societal ill-health were already evident in 1563. There is a subtle feeling of instability in Bruegel's Tower of Babel. The rocky core is relatively vertical, but the massive structure being build around it tilts slightly to the left. If the rock represents the essentials of the Christian faith, those fundamental propositions accepted by all Christians, it is being buried under bricks and stones, overlaid by the papacy with its monastic orders and elaborate ceremonies and lost to view as the Reformed sects add their multiple dogmas and various "novelties." When Bruegel returned to the subject again in his Small Tower of Babel (Figure 79), undated but probably painted a year or two later,70 the sense of imbalance remained: the tower became taller and more formidable, its rocky core no longer visible but only bricks and stones, and the clouds became larger, darker, and more ominous.

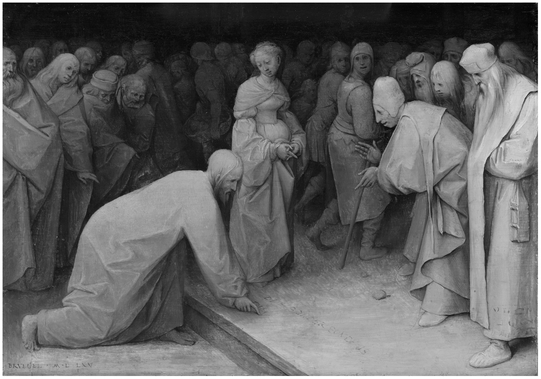

Because the image of the tower of Babel was used for their own ends by people on all sides of the Reformation controversy the artist was protected from any accusation of heresy The inherent ambiguity of the image also prohibits any firm conclusions about Bruegel's own position, although there is little in his art to suggest that he was aligned with either extreme. Bruegel's grisaille Jesus and the Woman Taken in Adultery (Figure 80) is an eloquent plea for tolerance, and while it is dated two years later the viewpoint is consistent with the Stoic stance typical of Bruegel's known associates in Antwerp at the time when he created the large Tower of Babel.71 Ancient Stoicism had the merit of providing guidance for a Christian at a time when fundamental institutions were undergoing profound and disruptive changes. It was a philosophy that gave historical legitimacy to a position of non-intervention, providing a venerable precedent for the role of the thoughtful spectator meditating on the world rather than trying to transform it. At its most extreme a Stoic attitude encouraged a pessimistic response, the position advanced by Sebastian Franck when he wrote that "degeneration is the law" and action futile:

79 Bruegel the Elder, Small Tower of Babel, c.1564, oil on panel. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

They have a foolish zeal who think they can make this devil's pigsty and perverted Babylon into a paradise and bring everything into order. It cannot be done. The devil's kingdom must remain to the end, confused and dark ... full of lies, disorder and injustice ... We try to improve things, but in vain. Experience has taught me this and has cooled my unseasonable zeal.

The moral, Franck concluded, is to leave things alone: "Cast not your pearls."72

Had experience taught Bruegel to "leave things alone"? Did this have a role in his decision to leave Antwerp for Brussels? In his Enchiridion Erasmus wrote, "... the prophet enjoins us to flee from the midst of Babylon."73 By 1563 positions had hardened: there was intransigence on both sides, with the extremists destroying any possibility for dialog and accommodation. The city of Antwerp was in a lawless, dangerous state, and it was difficult to remain a spectator when the religious dissension was polarizing positions and the uncommitted were accused of opportunism and lack of courage. Even the ordinary activities of daily life could prove troublesome and make it difficult to avoid offending one side or the other. Marc van Vaernewyck describes an incident in which the Count of Egmont attended Mass and offended everyone— the opponents of the church, "les gueux," because he attended Mass, and the Catholics because he knelt with his hat on.74

80 Bruegel the Elder, Jesus and the Woman Taken in Adultery, grisaille. The Samuel Courtauld Trust, Courtauld Institute of Art Gallery, London

In any era in which extremists drown out moderates, dogmatic assertions supplant dialog, and those who remain independent are attacked as timid and self-serving, it may take more courage to steer a middle course than to respond to the pressure and take sides. After Bruegel left Antwerp for Brussels the animosities already in evidence in 1563 exploded in the Iconoclastic Riots of 1566, an event followed by the terrible retaliation of the Spanish, disasters that would cause unbelievable hardships and a massive migration from the Low Countries.75 Bruegel's need to balance criticism and caution under these difficult circumstances precludes any definitive conclusions about his personal views, but the art he created serves as witness to the challenges he faced as he struggled to succeed in a competitive artistic environment, and to survive in a time of rising political and religious animosities.

1 Marijnissen (1988), p. 12. Bruegel's marriage to the daughter makes Van Mander's identification of Pieter Coecke van Aelst as Bruegel's master even more plausible.

2 Erasmus, CWE, vol. 31, no. 19, pp. 66-7.

3 Clair (1960), pp. 25-7.

4 For Plantin's troubles with the authorities see Voet (1969), vol. 2, pp. 34-44, Clair (1960), pp. 23-4, and Marnef (1996), p. 43.

5 Voet (1969), vol. 1, p. 23. For the Family of Love, see N. Mout, "The Family of Love (Huis de Liefde) of the Dutch Revolt," in A.C. Duke and C.A. Tamse, eds., Britain and the Netherlands, Church and State since the Reformation: Papers Delivered to the Seventh Anglo-Dutch Historical Conference (The Hague, 1981), pp. 76-93, and A. Hamilton, The Family of Love (Cambridge, 1981). For the religious situation in the Low Countries in Bruegel's time including the role of humanism, see J.J. Woltjer and M.E.H.N. Mout, "Settlements: The Netherlands," in Thomas A. Brady, Jr, Heiko A. Oberman, and James D. Tracy, eds., Handbook of European History, 1400-1600: Late Middle Ages, Renaissance and Reformation. 2 vols. (Leiden, 1994-95), vol. 2, pp. 386-415.

6 Ortelius, Album amicorum, fol. 66v and editor's notes, p. 54.

7 For the Bononia published at Basel in 1556 and Ceriol's troubles with the authorities see R.W. Truman, "Fadrique Furio Ceriol's Return to Spain from the Netherlands in 1564: Further Information on the Circumstances," BHR, 41 (1979), pp. 358-66.

8 Koeman (1964), p. 15.

9 Marnef (1996), pp. 96-7.

10 Brandt, History, vol. 1, bk. 4, p. 128.

11 Martial, Epigrams, IX. 27, 2, pp. 88-9.

12 Pliny, Natural History, XXXV. 36. 112, vol. 9, pp. 342-5.

13 Ovid, Metamorphoses, VIII, "Achelous," in Metamorphoses, trans. Horace Gregory (New York, 1958), pp. 232-3.

14 The concept of imitation inherited from the ancient world favored spirit over letter, the creative adaptation of the model over slavish imitation. In the satires Horace attacks his "imitatores" as a "pack of slaves" ("sevum pecus"), not because they copied, but because they "did so in superficial and trivial respects." See David West and Tony Woodman, Creative Imitation and Latin Literature (Cambridge, 1979), p. 2. See also Gordon Williams, Tradition and Originality in Roman Poetry (Oxford, 1968). Renaissance writers adopted the same position. Vida in De arte poetica states that one should follow the path of the old poets, but "conceal your thefts" (1976, p. 97). Vives, in his discussion of imitation, says the student should not imitate in a "stupid manner," but learn to "imitate truly," to "express himself according to his model," but not take stealthily and "stitch it into his own work" (On Education, 1913, pp 194-5). At its most successful such a strategy satisfied the audience that responded to the apparent artlessness of the work of art, and another that recognized the model and admired the artfulness with which it was being used. This passage follows Vives's discussion of Zeuxis's practice of combining multiple models. Here, as elsewhere, the intimacy of the connection between poetry and painting makes Renaissance literary theory relevant for the visual arts. See also David Quint, Origins and Originality in Renaissance Literature: Versions of the Source (New Haven and London, 1983).

15 C. Van de Velde, "The Painted Decorations of Floris's Hourse," in G. Cavalli-Bjorkman, ed., Netherlandish Mannerism: Papers Given at a Symposium in the Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, September 21-22, 1984 (Stockholm, 1985), pp. 127-34.

16 Hans Vlieghe, "The Fine and Decorative Arts in Antwerp's Golden Age," in O'Brien et al. (2001), p. 180, and Z.Z. Filipczak, Picturing Art in Antwerp (Princeton, 1987), p. 42.

17 Carl Van der Velde credits Floris with being the first to introduce studios organized in the Italian manner into the Low Countries. See his article "Frans Floris I," in Jane Turner, ed., The Dictionary of Art, 34 vols. (New York, 1996), vol. 2, pp. 222-3.

18 Carel Van Mander, Dutch and Flemish Painters: A Translation from the Schilderboeck, trans. Constant van de Wall (New York, 1936), p. 179. By the time Floris died in 1570, one year after Brueugel, his affairs had taken a different turn: his health was undermined by his profligate way of life and he was so deeply in debt that his possessions were liquidated in order to pay them.

19 Jervis Wegg, Antwerp, 1477-1559 (London, 1924), p. 339.

20 Louis Guicciardini, Description de touts les Pais-Bas, autrement appelés la Germanie Inferieure, ou Basse Allegmagne (Antwerp, 1582), p. 34.

21 For Floris see Van Mander, Het Schilder-Boeck (1604), pp. 238b-243b, and for Bruegel pp. 233a-234a.

22 For the poem and discussion of it see Freedberg (1989), pp. 62-3 and 65. As "invective," the kind of satire outlawed by the Romans according to Horace (Ars poetica, 281-4, pp. 474-5), the poem is quite different from Bruegel's witty and universalizing use of the genre in a painting such as the Dulle Griet, where satire is used to criticize the madness and folly of society as a whole and present popular philosophy in an entertaining way.

23 David Freedberg, "Allusions and Topicality in the Work of Pieter Bruegel: The Implications of a Forgotten Polemic," in Freedberg (1989), p. 63.

24 For the Suicide of Saul see Marijnissen (1988), pp. 172-9, Roberts-Jones (1974), pp. 226-9, Grossmann (1973), p. 193, and Sellink (2007), p. 173.

25 Marijnissen (1988), p. 172, and Grossmann (1973), p. 193.

26 Pliny, Natural History, XXXV. 36.110, vol. 9, pp. 342-3.

27 Reprod. in Orenstein (2001), p. 117.

28 Reprod. in ibid., p. 133. Orenstein suggests that the Flight into Egypt from the Large Landscapes was "designed by someone else," noting that Bruegel's name does not appear until the second state of the print, added it seems, to make it consistent with the rest of the series (ibid., p. 134).

29 M.J. Rodriguez-Salgado, "King, Bishop, Pawn? Philip II and Granvelle in the 1550's and 1560's," in Jonge and Janssens (2000), p. 110. See also Joanna Woodall, "Patronage and Portrayal: Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle's Relationship with Antonis Mor," in Jonge and Janssens (2000), pp. 245-77.

30 Grossmann (1973), p. 195.

31 Brandt, History, vol. 1, bk. 5, pp. 140-41. Apparently there were other possibilities for escape besides the main gates. Guicciardini mentions "issues secretes" in the ramparts; see Description de la cité d'Anvers par Louis Guicciardini, trans. François Belleforest, preface by Maurice Sabbe, introduction by Louis Strauss (Antwerp, 1920), p. 117.

32 J.L. Motley, The Rise of the Dutch Republic, 3 vols. (New York, 1868), vol. 1, p. 263.

33 For its relation with the Alchemist see Christine Meagan Armstrong, The Moralizing Prints of Cornelis Anthonisz (Princeton, 1990), p. 148 n. 53. Armstrong also relates it to a print by Cornelis Anthonisz, Sorgeloos (sixth scene), that is similarly concerned with the question of "foolishly incurred want."

34 Ausonius, epistle XV, vol. 2, p. 57.

35 Marnef (1996), p. 86.

36 Duke (1990), p. 64.

37 Some copies are in color. The one by Jan Brueghel the Elder illustrated here is typical of the father's work in the way the color red is dispersed throughout the painting. However, the grisaille examples may be closer to the father's original. See, for example, Klaus Ertz and Christa Nitze-Ertz, eds., Pieter Breughel der Jüngere, Jan Brueghel der Ältere: flämische Malerei um 1600, Tradition und Fortschritt. Kulturstiftung Ruhr Essen, exhib. cat. (Lingen, 1997) cats. 16 and 17, p. 118.

38 Polydore Vergil, Beginnings and Discoveries (1997), pp. 452-3.

39 Grossmann (1973), p. 25.

40 Polydore Vergil, On Discovery (2002), pp. 48-9.

41 For a wide-ranging study of the Tower of Babel see Ulrike B. Wegener, Die Faszination des Masslosen: Der Turmbau zu Babel von Pieter Bruegel bis Athanasius Kircher (Hildesheim, Zürich, and New York, 1995).

42 For Bruegel's Tower of Babel see S.A. Mansbach, "Pieter Bruegel's Tower of Babel," Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, 45 (1982), pp. 43-56. Mansbach also discusses the small Tower of Babel in Rotterdam dated after 1563. For a more extensive study of the Tower of Babel in art see Wegener (1995) and Sarah Elliston Weiner, "The Tower of Babel in Netherlandish Painting," unpub. Ph.D. diss., Columbia University, 1985.

43 Wegener (1995), p. 17. Another example (ibid., fig. 7) is more problematic.

44 Weiner (1985), p. 70.

45 Jan van Scorel's drawing Tower of Babel is reprod. in Orenstein (2001), fig. 37, p. 34.

46 For the etching see Armstrong (1990), pp. 106-14.

47 Orenstein (2001), pp. 212-16.

48 Robert Estienne, Thesausus latinae linguae (Paris, 1531). The passage is reprod. in Jolliffe (1956), p. 90.

49 Gilbert Highet, The Classical Tradition: Greek and Roman Influences on Western Literature (New York and Oxford, 1976), p. 183.

50 Thomas W. Best, The Humanist Ulrich von Hutten: A Reappraisal of his Humor (Chapel Hill, 1969), p. 35.

51 Guicciardini, Description de la cité d'Anvers (1920), p. 34.

52 See, for example, the woodcut by Jan de Gheet from 1515 in A.J.J. Delen, Iconographie van Antwerpen (Brussels, 1930), p. 70.

53 Sten Karling, The Stockholm University Collection of Paintings (Uppsala, 1978), pp. 74-5. The attribution is contested, but the point of the comparison still applies.

54 Williams and Jacquot (1957), vol. 2, p. 364. See also ibid., pl. 43 for the engraving The Fall of the Giants after Frans Floris. For the conflation of the gigantomachy and Babel in sixteenth-century literature see Quint (1983).

55 Brant, The Ship of Fools (1944), ch. 15, pp. 94-5. See also Luke 14:28-30.

56 Quoted in Sherrin Marshall, The Dutch Gentry, 1500-1650: Family, Faith and Fortune (New York, 1987), p. xxi.

57 Motley (1868), vol. 1, pp. 151-2.

58 Jonge (2000), p. 349. The author also suggests that Pieter Coecke may have been involved with Granvelle in earlier architectural projects (p. 357).

59 Vaernewijck, Troubles religieux (1905-6), p. 221.

60 Burgon (1839), vol. 2, p. 8.

61 Ibid., vol. 2, p. 54.

62 Crew (1973), p. 145.

63 Quoted in Marnef (1996), p. 124.

64 Weiner's argument (1985) that the reformers pre-empted the tower of Babel as an anti-papal symbol is more applicable after 1563. Luther is her principal source, but in 1563 the Lutherans were not the dominant reformist sect in the Low Countries. This is apparent, for example, by comparing Marnef's references (1996) to the Calvinist church in Antwerp with those to the Lutheran community.

65 Mansbach (1982) emphasizes the political struggle for power and suggests that Nimrod could be seen as Philip II (pp. 48-9).

66 For Castellio's problems with the Reformed see Erika Rummel, The Confessionalization of Humanism in Reformation Germany (Oxford, 2000), p. 67. Rummel also demonstrates the difficulties faced by those who wished to remain on the sidelines in the religious controversies.

67 Castellio, De haereticis, in Bainton (1951), pp. 31-2.

68 Erasmus, De lingua, CWE, vol. 29, p. 406.

69 E.A. Saunders, "A Heemskerck Commentary on Iconoclasm," Simiolus, 190 (1978-79), p. 82.

70 For the second version of the Tower of Babel and various interpretations of the tiny detail of a religious procession see Marijnissen (1988), pp. 219-22.

71 For Bruegel's Jesus and the Woman Taken in Adultery see ibid., pp. 288-9, where both the painting and the print after it are reproduced.

72 Bainton (1951), p. 98. See also Heyden-Roy (2008), pp. 962-3.

73 Erasmus, Erasmus and the Seamless Coat of Jesus, De sarcienda ecclesiae concordia (On Restoring the Unity of the Church), trans. H. Himelick (Bloomington, IN, 1971), p. 87. Erasmus probably had in mind Jeremiah's "flee ye from the midst of Babylon, and let every one save his own life."

74 Vaernewijck, Troubles religieux (1905-6), p. 201.

75 For these later events as reflected in Bruegel's art see Sullivan (1992), pp. 143-62.