CHAPTER 9

Feral Foragers: Scavenging and Recycling Food Resources

Scarcity is a central pillar of our economic and social structure. Without the threat of it, what would motivate all the hard work and sacrifice? The global players tell us that without the intensifying advancement of economies of scale, monocrop specialization, chemical pesticides and herbicides, and genetic engineering, there could never possibly be enough food for the mass of humanity to survive. To cite a classic example, Richard Nixon’s secretary of agriculture, Earl Butz, pronounced thirty-some years ago that “before we go back to an organic agriculture in this country, somebody must decide which fifty million Americans we are going to let starve or go hungry.”1 Similarly, in today’s debates over biotechnology those who oppose genetically modified crops are often accused of standing in the way of progress that could alleviate hunger, malnutrition, and poverty. Hunger is the ultimate unquestionable justification, and it has been used to manipulate all sorts of political debates.

But are hunger, malnutrition, and poverty really caused by an overall shortage of food resources? I am inclined to believe that there is plenty of food growing around the world for everyone to be adequately fed. Hunger is not caused by insufficient total resources but rather by the uneven distribution of those resources. “While hunger is real, scarcity is an illusion,” write Frances Moore Lappé and Joseph Collins.2

Even with all the “improvements” in agriculture, hunger continues to be widespread. After a brief period of reduction in the estimated numbers of hungry people around the world, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization now reports that hunger is on the rise, with 852 million people “chronically hungry” and five million children dying from hunger every year.3 Even within the United States the population of the hungry is expanding. U.S. Department of Agriculture statistics counted 38.2 million people in 2004—about thirteen percent of the total population—in households suffering from hunger and food insecurity, up from thirty-one million in 1999.4

Yet in spite of the fact that so many people in the United States are hungry, an incredible quantity of food gets discarded. Timothy Jones, an anthropologist at the University of Arizona who spent ten years picking through trash and measuring food loss, concludes that nearly half the U.S. food supply goes to waste. Waste begins in the field, where an average of 12 percent of U.S. crops are plowed under, often unharvested for economic reasons. The greatest sources of wasted food are retailers and consumers; both regularly overstock and end up discarding perishable items. Food retailers in the United States throw away $30 to $40 billion worth of food each year, and households toss out 14 percent of the food they purchase. Jones estimates that an average family of four discards $590 worth of groceries per year, adding up to $43 billion for U.S. households as a group. Altogether $100 billion worth of food, half the U.S. supply, goes to waste.5 Many activists are tapping into this colossal waste stream, rescuing food in order to redistribute it, as well as utilizing food that is beyond edibility as resources for fuel and fertilizer.

Tapping into the Waste Stream

In keeping with the simple truth of the slogan “Reduce, reuse, recycle,” the place to start is reducing waste in our own lives. Waste is not inevitable; we create it. Each of us can reduce waste by being realistic about how much to buy and prepare, storing leftovers conscientiously, making creative use of them, and composting organic materials. We can also avoid overly packaged foods. Packaging accounted for 31.7 percent of the municipal solid waste generated in the United States in 2003, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.6

Beyond minimizing waste, many creative scavengers go out in search of waste to reuse and recycle through transformative magic. While this chapter focuses on food reclamation efforts, activists everywhere are applying similar creativity to other related waste streams. For example, Julia Christensen has undertaken an exciting project called How Communities Are Re-Using the Big Box, in which she is documenting creative reuses of massive “big box” retail stores that often become obsolete in just a few years and move to even bigger spaces.

Food reclamation projects are organized in many different ways and at many varied scales. Sometimes it’s just someone with his or her eyes open who notices unharvested crops and gathers them. This is called gleaning. Common law recognizes the ancient right of people to come onto fields after harvest and take what they can find. My neighbor Krista harvests excess berries and other fruit from all our neighbors to put up for winter. Other friends, Buck and Greg, scope out fruit wherever they drive and turn their roadside gleaning into wines, meads, and brandies. These accomplished spinners and fiber artists have also gleaned vast quantities of cotton, which they manually deseed and transform into gorgeous garments. And many other people I know and have written about in these pages are accomplished gleaners.

Food Not Bombs logo.

Food Not Bombs logo.

People have also joined together in many different places to collect discarded food and get it into the hands and mouths of people who need it. Food Not Bombs (FNB) is a decentralized but extremely widespread grassroots movement—“a revolutionary mutual-aid community” in the words of the Detroit group—of people engaging in food redistribution efforts. The movement started in 1981 in Boston and Cambridge, Massachusetts, with a group of friends who were active in campaigns against nuclear weapons and power. The name Food Not Bombs evolved from a stencil they used to spray-paint on sidewalks at the exits of supermarkets: “Money for food, not for bombs.” The activists first used “Food Not Bombs” as the name of their group in an action, originally conceptualized as street theater, in which they served free food and created a soup line outside the Federal Reserve Bank in Boston in March 1981, as the stockholders of the First National Bank of Boston (a major investor in nuclear power) met inside:

As nuclear power protesters, we wanted to do street theater that would remind people of a 1930s-style soup kitchen, to highlight the waste of valuable resources on capital-intensive projects such as nuclear power while many people in this country went hungry and homeless. At first, we thought we would have actors play the homeless, but then we realized we could get people who actually were homeless to participate. . . . We collected day-old bread from a bakery and some fruit and vegetables from the local co-op on the morning of the stockholders’ meeting and cooked a huge pot of soup. We set up a table at the Federal Reserve Building, and to our surprise, over one hundred people showed up for a meal.7

Once the group learned how easy it was to collect surplus food, and what tremendous demand there was for it, they started collecting and serving food regularly. With the surplus perishables of a food co-op, a local tofu manufacturer, a bakery, and eventually more enterprises, the original FNB collective distributed food every other day to shelters in Boston’s South End neighborhood. They also became a regular fixture serving food at protest events and began to inspire activists in other places, including San Francisco and Washington, D.C., to do similarly.

FNB unites protest with service and has a very down-to-earth appeal. “It will take imagination and work to create a world without bombs,” explain C. T. Lawrence Butler and Keith McHenry, of the original FNB collective, in their book Food Not Bombs:

Food Not Bombs recognizes our part as providing sustenance for people at demonstrations and events so that they can continue participating in the long-term struggle against militarism. We also make bringing our message to other progressive movements part of our mission. We attend other organizations’ events and support coalition-building whenever possible. We work against the perspective of scarcity that causes many people to fear cooperation among groups. They believe they must keep apart to preserve their resources, so we try to encourage feelings of abundance and the recognition that if we cooperate together, all become stronger.

Being at the center of the action with our food is part of our vision. Sometimes we organize the event; sometimes we provide food at other organizations’ events. Providing food is more than just a good idea. It is a necessity. Either the movement can seek food services from the outside and be dependent on businesses that may not be progressive, or we can provide for ourselves. Clearly, it is Food Not Bombs’ position that providing for our own basic needs, in ways that comprehensively support the movement, is far more empowering. We have provided food at long-term, direct actions, such as the annual Peace Encampment sponsored by the American Peace Test at the Nevada Nuclear Weapons Test Site; to tent cities that highlight homelessness and hunger in San Francisco, Boston, New York, and Washington, D.C.; and for the regular feeding of the homeless in highly visible locations throughout the country.8

The San Francisco FNB group began serving food in Golden Gate Park every week. After three months without incident, one day in August 1988 they received a visit from police, who told them they could no longer serve food there. The group decided to defy the police and continue serving food to the city’s hungry and homeless. The following Monday, when the group set up their free food in the same spot, they were surrounded by lines of riot police, and nine servers were arrested. This brought FNB tremendous publicity and solidarity. “Arresting FNB members proved to be a major political miscalculation on the part of City Hall and an enormous break for FNB,” according to one account. “People being arrested for sharing free food made the headlines and greatly expanded interest in the group.”9 As FNB’s support grew, the San Francisco police stubbornly persisted, and arrests of FNB activists there continued on and off for a decade; by 1997 there had been over a thousand arrests, which spurred action and inspired FNB groups far and wide.

The grassroots spread of FNB has been accomplished primarily through decentralized underground media: word of mouth, flyers, zines, the Internet, and punk music. One of the lessons drawn by FNB in the San Francisco experience is never to apply for a permit, for just prior to the start of the arrests the San Francisco group had requested a permit from the city. Butler and McHenry recommend to fledgling FNB chapters, “The revolution needs no permit.”

The Revolution Needs No Permit By C. T. Lawrence Butler and Keith McHenry

Sometimes people argue that it makes the city happy if you get a permit so they know you are using some city sidewalk or park. You give them the name of the organization, its mailing address, and a phone number, and they give you a permit. If the permit policy is really that simple, you might look into it, but avoid giving the identity of your group until you know for sure.

Case in point: on July 11, 1988, after serving for several months without city interference, the San Francisco Food Not Bombs group wrote a simple, one-page permit request to the Recreation and Parks Department at the suggestion of some community organizers. This unfortunately alerted the government to the meal distribution program, and gave it an opportunity to deny us a permit. It then used this as an excuse to harass the food table and arrest volunteers.

Although the government may create reasons for denying you a permit, you should not be intimidated. Make it clear that you are willing to adopt any proposal that will make your operation safer and more successful, but also that you will not agree to any demand making it impossible for you to continue your operation. Even after long hours of meeting with government officials, hard-earned permits can be revoked at any moment. From the government’s point of view, a permit is something it can take away whenever it wants. (Remember Indian treaties?) Because of this, we strongly recommended that you not contact the local government. The revolution needs no permit.

Excerpted from Food Not Bombs (Tucson, AZ: See Sharp Press, 1992, revised 2000). Used by permission.

“Food Not Bombs is one of the fastest-growing revolutionary movements active today and is gaining momentum,” proclaims a FNB flyer. “There are hundreds of autonomous chapters sharing free vegetarian food with hungry people and protesting war and poverty throughout the Americas, Europe, Asia, and Australia.” Indeed, I’ve encountered FNB groups myself at protest events for the past decade, and I’ve gotten to know FNB folks in several different cities.

Some of the FNB collectives have endured over time; others were fleeting, short-lived experiments by young people trying to do something positive in the world. My friend Socket, who was in FNB in Northampton, Massachusetts, while in college and then later in Oakland, California, calls FNB “gateway activism.” By that, I understand he/she (Socket likes to cross between the two and mostly resides somewhere in between) to mean that FNB is an accessible, easy-to-plug-into form of activism with tangible rewards that is often a port of entry through which people find their way into other activist projects.

FNB groups use many different methods for obtaining food surpluses, among them picking through supermarket dumpsters, which are generally a dependable source. Socket joined me one night for an outing of dumpster-diving with Derrick, a Nashville FNB friend whose passion for dumpster-diving for food is exceeded only by his passion for dumpster-diving for fashions. The Nashville FNB group generally hits the dumpsters Friday and Saturday nights and serves meals Saturday and Sunday afternoons. I’ve been a lifelong trash picker and compost rescuer, so the concept of digging through a dumpster and eating food from it is not intrinsically troubling to me. However, my preconceived notion of what our haul would be was lots of junk, such as stale packaged dougnuts. This was because I have heard some dumpster divers pride themselves on their “freegan” or “opportunivore” adaptability.

What shocked me as we made our rounds was how much perfectly fine produce we found. Everything in the store must look perfect. Anything with the slightest blemish, or even approaching the prime it will soon be beyond, gets tossed. The biggest supermarket chains use compacting dumpsters, and some of them even spray bleach into the dumpsters as a deterrent to dumpster-divers. Dumpster-divers learn through experience where the best dumpsters are.

We wore headlamp-style flashlights so we could see in the dark and have our hands free. Our first stop was Food Lion, where Derrick climbed up into the dumpster and started handing things down to Socket and me. The first item was portobello mushrooms! We rejected some that were smelly, but most were still fine. Then red, yellow, and orange bell peppers, radishes, platters of precut vegetable crudités, cauliflowers, and something I had never seen before, individually plastic-wrapped “Potatoh!”s. In a second dumpster at the same store we found bagels, pitas, and sandwich rolls. In just this one stop we had found plenty of reasonably wholesome food to feed ourselves for days.

But we weren’t feeding ourselves; we were gathering food for a group effort to cook enough food for about thirty-five people in a plaza in downtown Nashville. Our next stop was the Dollar General Market. I was on my guard here because I noticed a police car as we turned into the empty parking lot, and I imagined that dumpster-diving was technically illegal. Derrick says he’s been stopped and questioned a few times by police as he’s dumpster-dived, but he’s never been arrested. This dumpster turned out to be our tropical paradise, with lovely ripe pineapples and key limes, as well as cantaloupes and tomatoes. And the police didn’t follow us in.

Our next stop was a local produce market. Here I got so excited by what I could see that I jumped into the dumpster myself. Right there on top were jalapeños, tomatillos, and big Italian eggplants. As I excavated deeper, beneath layers of broken-down cardboard boxes and food in various stages of decay, I unearthed scallions, cilantro, grapes, zucchini, and slender curvy Asian eggplants. When I was ready to document our bounty—still in the dumpster—I realized that I had lost my notebook in there. So I had to dig around again until I found it. We then visited another Food Lion, where we found cookies, canisters of pressurized whipped cream, ricotta cheese, bags of precut stir-fry vegetables, and more pineapples and portobello mushrooms. Our last stop, at a discount supermarket called Aldi, yielded more cauliflowers, apples, peppers, onions, and a couple of bags of powdered mini donuts, which Derrick considers a sign of good luck.

Dumpster-diving has attracted many committed devotees. Dumpster-divers take great satisfaction from meeting their needs and desires out of other people’s waste, and these resourceful scavengers help support thriving subcultures everywhere. “After years of dumpster-diving, it came to be expected that each dumpster score would top the previous, and that there was in fact nothing the dumpster wouldn’t provide,” writes the anonymous author of Evasion.10

A zine called dumpsterland, by a self-proclaimed hobo puppeteer named Dave, contained some excellent dumpster-diving tips:

Get out the yellow pages. Yes, it’s true! All great dumpsters lie within that precious resource. Every store and every distributor makes waste. Some may be harder to get at, some impossible, but this is where you begin. . . .

Most frustration with dumpster-diving comes from hitting them on trash pickup days. . . . Go search it out on Wednesday and Saturday, after closing time. If that doesn’t do much go on Monday and Thursday. Don’t give up! . . .

Scratch below the surface. The top layer of any dumpster is rarely indicative of what treasures are buried within. Get in there! Root around! Move those top bags aside, dammit. Do you want to buy potatoes or do you want them for free? . . .

The subtle nuances will come to you. Don’t ever forget to leave the area around the dumpster as clean or cleaner than you found it. Also, untie bags rather than rip them open if you can. . . .

As an aside, dumpsters are not sustainable. Throwing away food, clothing, building materials, and everything else imaginable is nasty business, utterly repulsive and sinister. I dumpster-dive because it exists.11

Dumpsters are not the only sources of food waste. Often, recyclers can make connections with food businesses to collect their unwanted food and take it before it enters the waste stream. For example, every week my fellow communard Sister Soami collects huge garbage bags full of day-old bread at an upscale Nashville bakery and spends a day dropping off loaves for all our neighbors—like a sourdough Santa.

And, of course, people who work in food businesses everywhere take home excess production, imperfect seconds, or what they can get away with. My friend Ed brings home fish from the dock where he works unloading freshly caught fish from boats and preparing them for auction. Ed’s daughter Caity works in a bakery and brings home all sorts of delectable pastries, cakes, and cookies that are no longer fresh enough to sell after the first day. Ideally food gets rescued, diverted, or liberated before it gets thrown into a dumpster.

In Asheville, North Carolina, friends of mine are part of what one of them describes as “community-supported activism.” This is a loose network of individuals and organizations who pick up the discarded food generated by a thriving, large health-food supermarket and distribute it widely. The participants all emphasize that the key to maintaining such food pickup relationships is consistency and reliability. Their distribution network has received huge quantities of fine food, including cases of frozen organic meat products just past their expiration dates but still frozen, never thawed, and perfectly delicious.

FNB—for reasons of both ideology and food safety—has generally remained in the realm of vegetarian food; perhaps cheese sometimes, but generally no meat. The Asheville distribution network crosses the line into frozen meats. But pulling meat, thawed for who knows how long, out of a dumpster sounds just too sketchy for most people. Which brings us to our next topic: dead animals from the road.

Roadkill Radicals

If you pay attention and look at the road while driving (or, even more so, while walking or biking), you will inevitably encounter roadkill. Animals moving across the landscape are often unavoidable prey at fifty-five miles per hour. Little systematic counting has been done, but extrapolating from data collected by road crews in Ohio, one analysis estimates there are an average of more than one hundred million road-kill victims in the United States each year.12 Dr. Splatt, the pseudonym of a high-school science teacher who for thirteen years has organized students around New England to participate in a roadkill census, comes up with a very similar estimate of 250,000 animals killed by cars in the United States on an average day.13 Some people see food in these unfortunate victims of our car culture and regularly pick roadkill up off the road to take home and eat.

A few passionate souls I have encountered eat roadkill almost every day. My neighbors Casper and Pixey bring roadkill stews to our potlucks. For a while they did their frying in grease rendered from a roadkill bear they came across in the mountains. On one of my friends Terra and Natalie’s visits, they had strips of roadkill venisons splayed across their dashboard drying into jerky.

When I first met Terra, she was vegan. Then she and her boyfriend Ursus—who has the word vegan tattooed onto his shin—discovered roadkill and quickly became roadkill carnivores. In her zine, The Feral Forager, Terra explains how they came to start eating roadkill:

Our first feral feast of roadkill was on spring equinox of 2002. That past winter we had experimented with skinning and tanning, using a possum and a raccoon we had found on the roadside. . . . On spring equinox we were driving in the suburbs of a large southeastern city and spotted a fox dead on the roadside. Our first thought was what a great fur it would make. We scraped it up (it wasn’t very mangled at all) and took it to our friends’ house downtown, and Ursus skinned it in the backyard while our friends assisted. When it was all done and hanging gutless and skinless from a tree, it was like some collective epiphany: why not eat it? There was a great firepit there and several willing “freegans,” along with a few pretty hardcore vegans (including Ursus) who raised no protest. After a couple hours on a spit, the grey fox was edible. I guess it was something about the start of a new season—it was almost ritualistic, without trying to make it so. Some stood by and watched while four or five of us feasted on the fox. Ursus, a hardcore vegan, was perhaps the most voracious. There was something primal about his eating—like a wild man caged for years eating only bagels and bananas. Ursus tanned the skin and later wore it around his neck like a scarf.14

Terra, Ursus, Natalie, and other members of the Wildroots Collective in western North Carolina now eat roadkill nearly every day, have a good supply put away in a freezer, and have tried dozens of different species of animals found dead on roadsides.

The Wildroots folks have become enthusiastic promoters of roadkill and work hard to spread information and skills to empower other people to tap into this huge available food supply. Members of the collective do a good bit of traveling on the do-it-yourself skillsharing circuit, teaching people how to judge the edibility of a dead animal on the road and guiding them through the experience of skinning and cleaning a small animal. At the 2005 Food For Life gathering at the Sequatchie Valley Institute/Moonshadow, one of the most memorable events was the hands-on roadkill workshop, in which we learned about the cleaning, skinning, and butchering of roadkill animals. The Wildroots folks brought a roadkill groundhog with them, and our friend Justin, another roadkill enthusiast, brought a squirrel he had found on his bike ride to the gathering. (The more slowly you travel, the more you notice not only roadkill but all sorts of roadside harvesting possibilities.)

People enthusiastically took front-row seats to see these animals get skinned. Some people shuddered in horror, had to look away, or otherwise expressed their squeamishness. But most people watched quietly, fascinated, as Natalie coached Dylan, a previously uninitiated thirteen-year-old (there with his family) through the skinning of the squirrel, and Jenny and Justin skinned the groundhog. Direct experiential education like this can be transformative. Laurel Luddite wrote about her first roadkill butchering experience, “The responsibility made me nervous at first. As I cut I began to feel confident that not only could I butcher this deer, but I could also fulfill my need for food whenever I saw some lying by the side of the road.”15

Roadkill has been a source of food for poor people since there have been cars. In American culture eating roadkill generally has a pejorative classist connotation, epitomizing ignorant hillbilly behavior. Now Wildroots and other enthusiasts are embracing roadkill with a political ideology, rejecting the values of consumer culture by “transforming dishonored victims of the petroleum age into food which nourishes, and clothing which warms.”16 Beyond ideology, they are spreading practical information and skills to empower people.

Terra’s zine, The Feral Forager, offers a basic primer for safely eating roadkill:

Picking up roadkill is a good way to get fresh, wild, totally free-range and organic meat for absolutely free. When you find the roadkill you should try to determine if it is edible or not. If you saw the animal get hit then it’s obviously fit to eat (although you may have to put it out of its misery). If the critter is flattened into a pancake in the middle of the highway then it’s probably best to leave it. Most of the time (not always), good ones will be sitting off the road or in a median where [they aren’t] constantly being pulverized.

Sometimes it can be hard to determine how fresh a carcass is. A lot of factors can contribute to how fast the meat spoils, especially temperature. Obviously, roadkill will stay fresher longer in colder weather and spoil faster in warmer weather. It’s best to go case by case and follow your instincts. Here are some considerations to help you decide:

• If it is covered in flies or maggots or other insects it’s probably no good.

• If it smells like rotting flesh it’s probably spoiled, although it is common for dead animals’ bowels to release excrement or gas upon impact or when you move the carcass.

• If its eyes are clouded over white it’s probably not too fresh (though likely still edible).

• If there are fleas on the animal there’s a good chance it’s still edible.

• If it’s completely mangled, it’s probably not worth the effort.

Rigor mortis (when the animal stiffens) sets in pretty quickly. Most of the animals we’ve eaten have been stiff. There’s no reason to assume the animal is spoiled just because it’s stiff. . . .

Potential Risks of Eating Roadkill: One of the most severe risks of roadkill is rabies. In order to assure your safety from this deadly serious brain inflammation, you may want to use rubber gloves when gutting and skinning any warm-blooded animal (warm blooded as in mammals and birds, not in regard to blood temperature). If you don’t feel the need to exercise this absolute caution, at least make sure you don’t have any open wounds on your hands or skin that touches the animal. Roadkill is usually safe from rabies because it dies quickly when the animal dies. Also, rabies will cook out of the carcass. Generally speaking, boiling the animal first (rather than just grilling it) is a good idea, especially if it’s a notorious rabies carrier (like raccoons, skunks, and foxes).17

Wild Food Scavenging

Roadkill meat is just one element of a broader wild-foods foraging-gathering ethic that many food activists embrace. “If everyone simply stopped to take advantage of the most obvious and abundant wild foods growing a hundred yards back from the roadside on his or her way home from work,” writes Gary Paul Nabhan, “I’m sure that radical changes in our society’s entire perception of foods and their costs would follow.”18 I touched briefly upon the topic of weed eating in the recipe for chickweed pesto in chapter 1 (see Recipe: Chickweed Pesto), but I cannot reiterate strongly enough that many wild plants—both indigenous natives and introduced plants that have naturalized—are more densely nutritious than the cultivated plants for which they are usually weeded out. They are adapted to the environment, hardy, and self-sufficient—all qualities we need. Also, because so many different plants are edible, regular foragers eat a far greater variety of plants—each with unique phytochemical elements—than people who rely exclusively on cultivated crops.

The reasons why people forage for wild food go beyond sustenance. Many activists I meet view foraging as a path toward liberation from corporate groceries, the grind of a nine-to-five job, and other trappings of civilization. “In our own quests to develop these skills we have come to realize that we are like infants,” the members of the Wildroots Collective reflect. “Instead of learning skills essential to living, such as crafting tools from earthen materials, skinning animals, making clothes, identifying and preparing wild food and medicinal plants, our educations have trained us to be good little participants in a global capitalist system, alienated from our survival, dependent on the technological-industrial, resource-extracting, land-gobbling, animal-enslaving, indigenous-culture-destroying machine.”19

Perhaps the most passionate forager I have crossed paths with is Fritz, a punky young transgendered traveler who searches for wild foods everywhere he goes—and finds them. Fritz always impresses me with not only his knowledge of wild edibles, but also his persistence in harvesting and processing them, which are the limiting factors for many people in the know. I fondly recall Fritz disappearing into the woods here one spring afternoon and returning with a full basket of tiny tooth-wort roots, which he painstakingly grated into a potent, delicious, horseradish-like sauce. Another foraging role model in my life is an old Japanese man I met in the Kauai rain forest when I was on a solo backpacking adventure in Hawaii long ago. He claimed to have lived in the forest for years on wild food and hikers’ excess provisions. I shared some of my food with him, and he pointed out to me the leaves of sweet potato, a perennial plant in that climate offering abundant fresh greens. Both the man and the sweet potatoes were domesticates gone feral.

Empower yourself by expanding your awareness of wild foods. “The average American can identify three hundred corporate logos but only about seventeen plants,” observes Food Not Lawns founder Heather Flores (also known as Heather Humus). “This is pathetic. There are thirty thousand edible plant species known to humans.”20 Books can sometimes help you identify edibles, but nothing compares to getting out with someone experienced. My earliest edible plant walks were as a kid, with my cousin David, armed with a copy of Euell Gibbons’s Stalking the Wild Asparagus. We never did find any asparagus, but we did find wild grapes. Years later I went on weed walks in New York’s Central Park with my friend Judith. Her enthusiasm for what she introduced to me as “plant allies” was infectious, and I started knowing some common weeds, eating them, and getting to know more.

I tend to be very adventurous about tasting plants I don’t know; my rule of thumb is that it’s okay to taste unknown plants (though not fungi) so long as you experiment slowly. Smell before you taste. Taste just a tiny bit. Chew it well, mix it with saliva, and see how it feels in your mouth. If it tastes unpleasant or you start reacting in some strange way, spit it out and don’t eat any more. If it feels okay in your mouth, swallow. Wait a little while. Taste some more, if you want, but never eat a lot on a first encounter. See how it sits with you and come back for more tomorrow.

Wild Mushrooms: A Taste of Enchantment By Alan Muskat

What do you get when you cross the Iron Chef with Fear Factor and Survivor? You get most Americans’ view of eating wild mushrooms. Fungilliterati notwithstanding, of the ten thousand species of mushrooms identified in North America, maybe twelve are known to be lethal. But before you cast caution to the wind, know that some of these deadly dozen are quite common. The “destroying angel” and the “death cap” are responsible for nearly all mushroom-induced fatalities. So although there certainly are deadly mushrooms out there, there are very few to watch out for. Once you know what to look for, these are as easy to pick out as carrots from cauliflower.

What about mushrooms that won’t kill you but will make you wish you were dead? There are a few of these as well. However, the vast majority of “poisonous” mushrooms merely cause mild to severe stomach upset. Granted, this is enough to make some of us not want to ever eat wild mushrooms again. Out of ten thousand species identified in North America, only 250 are known to be more or less toxic. Of these, only twenty are common.

What about the other 9,750? As far as we know, they’re harmless. But then again, we don’t know everything. That’s where you come in.

Actually, it’s perfectly safe to touch or smell nearly every wild mushroom, including the deadly ones. You’ll find that mushrooms can smell like seafood, chlorine, cucumbers, vinyl, almonds, anise, marzipan, maple syrup, ink, garlic, dog mess, and raw potatoes—and most of these are edible. In fact, most mycophagists (that’s mushroom-eaters) agree that at least two hundred types of wild mushrooms are worth eating.

Most of us would be quite content with a basketful of morels, chanterelles, porcini, meadow mushrooms (the “wild portabello”), matsutake, or chicken-of-the-woods. But many more varieties are edible, medicinal, or both. Each is as nutritious as it is delicious, and many can be found growing wild in most of North America—maybe even in your own woods or backyard, where shopping is a pleasure.

At nature’s supermarket, the produce is always local, organic, fresh, and free. This is one place where you get what you don’t pay for. Learn to gather your own; you’ll be glad so few people do!

Excerpted from Wild Mushrooms: A Taste of Enchantment, 4th ed. (Asheville, NC: self-published, 2004). Used by permission.

Many knowledgeable teachers are taking up the activist work of spreading important wild-foods wisdom through grassroots experiential education. My teaching partner Frank Cook—together we have taught many fermentation and wild food foraging workshops—is deeply devoted to walking the land and meeting the plants wherever he goes. He frequently organizes plant walks and enjoys helping people break through what he calls “the green wall” that prevents them from getting to know plants and exploring their world. My friend Crazy Owl is another irrepressible spirit who loves to share his considerable plant foraging knowledge, inviting all who will come to join him on walks into “the enchanted forest.”

Teachers are everywhere. In New York City Steve Brill has been leading wild-food foraging walks in city parks since 1982. He became notorious in 1986 after he was arrested for the crime of harvesting dandelions. Reported the Associated Press:

Two park rangers disguised as nature-lovers used marked bills, a surveillance camera and walkie-talkie to get the goods on the bespectacled botanist who calls himself “Wildman.” . . . Brill insisted he’s not a criminal. “We take only renewable resources,” he said. “We pick maybe one dandelion weed out of hundreds of thousands that are mowed down. I’m just trying to get people into nature, to show them they can touch things, and smell things and taste them.”21

Brill is still leading wild-food walks—more than ninety in 2005 alone—all around the New York metropolitan area. Chances are someone near you is leading foraging walks, or perhaps your calling is to become such a guide.

Foraging knowledge is not limited to plants. There is a huge movement of mycology hobbyists who organize mushroom walks and fungus forays in their areas. My friend Alan Muskat, self-described “mythic mycologist and epicure of the obscure,” has long experience harvesting edible and medicinal mushrooms. He sometimes sells wild mushrooms to restaurants, and for years he has led classes and walks. He has also written and self-published a book, Wild Mushrooms: A Taste of Enchantment, to help people get started. He advises foragers not to be overly goal-oriented: “Don’t go in the woods just to fill your basket. Like life, mushroom hunting is a great exercise in non-attachment, in letting go of expectations, because you never know what you will or won’t find.”22

Another whole realm of exciting foraging exploration is entomophagy, or the use of insects as food. Insects are plentiful in most places, and though our culture has generally made eating insects taboo, many people around the world regularly eat insects for sustenance. Some foraging activists are learning and sharing this knowledge. The more diversified our foraging skills, the more we will find to eat on any given outing.

An extreme perspective on foraging presents it as a wholesale rejection of agriculture. The anonymous author of the zine Beyond Agriculture invites readers to join the “ongoing Feral Jihad against Agriculture.”23 Euell Gibbons, in his 1966 book Stalking the Healthful Herbs, writes, “We would be better off nutritionally if we threw away the crops we so laboriously raise in our fields and gardens and ate the weeds that grow with no encouragement from us.”24 In 1988 John Zerzan, a prominent voice in recent “anarcho-primitive” literature, published in the anarchist newspaper Fifth Estate an essay titled “Agriculture—Essence of Civilization,” which has been much referred to since. “Agriculture is the birth of production,” writes Zerzan. “The land itself becomes an instrument of production and the planet’s species its objects. Wild or tame, weeds or crops speak of that duality that cripples the soul of our being, ushering in, relatively quickly, the despotism, war and impoverishment of high civilization over the great length of that earlier oneness with nature.”25 Zerzan and others advocate not for a return to smaller-scale, more sustainable farming but rather forgoing agriculture as we know it and reintegrating as hunter-gatherers. Some descriptive phrases I’ve heard to describe this reintegration process are “going feral” and “rewilding.”

Personally, I don’t think this is an either/or choice. We need both more foraging of wild plants and more local cultivation; they are not inherently in conflict. Some visionary idealists see opportunities for foraging and cultivation to synthesize and complement one another. After all, the origins of farming involved simply encouraging the proliferation of wild edibles, and holistic models of gardening, such as permaculture, seek such integration. One compelling philosophy of living and eating is called “paradise gardening,” an intensified form foraging that has been articulated, practiced, and promoted by a North Carolina man named Joe Hollis.

Paradise gardening is a way of life which serves to maintain the garden, and is in turn maintained by it. . . . Like any other creature, we are our niche. . . . Our goal is to “naturalize” ourselves in the environment. This will involve changing ourselves and changing the environment: convergence toward a “fit.” . . . The process of Paradise Gardening involves . . . the (re)integration of needs: not to the market for food, the spa for exercise, the doctor for healing, theatre for entertainment, school for learning, studio to create, church for inspiration, etc., but to the garden for all these at the same time. Enriching the garden by naturalizing useful and beautiful species and learning to incorporate them into our lives. We begin, of course, with the present and potential natural vegetation, to which may be added species introductions from similar areas worldwide; then slight modifications of the environment—micro-habitat enhancement—and the resultant possibilities for new species: a palette of plants, a cornucopia never available to previous generations.26

Hollis emphasizes important differences between paradise gardening and agriculture as we know it: “Our addiction to annual species and disturbed habitats has put us at odds with the main thrust of the biosphere (and ourselves).” As an alternative, he suggests greater reliance on perennials, which grow and produce more each year without requiring the soil to be touched. Hollis also emphasizes urgency: “We live during a narrow ‘window of opportunity.’ Having come, at least, to a realization that a revolutionary shift of consciousness and lifestyle is required, we find that we have only a few generations to do it in, before it will be too late.”

Insects: A Forgotten Delicacy By Terra

Most people in North America will quiver at the thought of eating bugs. In fact even some survival guides mention eating bugs as “the unthinkable.” But in spite of this blatant specieism, everyone (including the strictest vegan) who’s ever eaten anything has unintentionally eaten millions of insects.

Insects are in fact a very nutritious food source. They are high in fat, protein, and many other vitamins, including B12. That is part of the reason why indigenous people around the world seek out these abundant food sources. . . . For those of us modern feral folk who have gotten past the mental block of cultural conditioning, we have discovered that insects are not only nutritious but can also be very tasty. But don’t go out eating everything you see—some are poisonous or can cause allergies. . . . Here is a list of edible bugs that I have tried and how you can prepare them:

Grasshoppers and Crickets: If you have the patience to catch them! Like all hard-shelled insects you should cook them to kill any parasites, and you may want to remove the wings and legs. I have found they are best roasted in a pan or over a fire shish-kebob style. (Kill them first if you can, and they can hop around even with their heads off.) They are surprisingly tasty and filling—they taste something like popcorn. Crickets are incredibly high in calcium and potassium.

Ants and Their Eggs: One of the best wilderness foods I have ever eaten! The large black carpenter ants are the choice ones to go for. All ant eggs are edible and can be eaten raw or cooked. The carpenter ant’s eggs taste a lot like grains when boiled, and taste like eggs when roasted. I hear that small ant eggs can be eaten raw and taste like couscous, but the only time I tried this it tasted like a hundred ants biting my tongue (there were live ants on the eggs too). If you’re cooking the eggs you can add the ants right in there with them. I wouldn’t suggest eating fire ants, but then again I’ve never tried to, and the chemical that causes the burning sensation may cook out (let us know if you try this).

Rolly Pollies, or Pill Bugs: Rolly Pollies are actually a crustacean and not an insect (just think of them as land shrimp). They can be roasted whole and taste a little like popcorn.

Grubs (Beetle Larvae): All beetle larvae can be eaten raw; they taste kind of fishy. They can be added to soups, stews, and stir-fries. They can also be roasted, after which these little fat-filled protein snacks taste a lot like popcorn. Snails and Slugs (Escargot):

Snails can be shelled (throw them in boiling water first) and sautéed with garlic (wild or cultivated), or added to soups. Slugs probably present the biggest challenge getting over the mental block. They can be prepared like snails only you don’t have to shell them.

Earthworms: These subterranean squirmers are packed with soil minerals and microorganisms that simply can’t be substituted in our modern vegan diets. They can be eaten alive, added to stews, or dried in the sun on a hot rock, and then ground into a very nutritious flour, which can be used as a soup thickener, or cut with other flours and used in flatbreads or other baking.

For more information check out www.food-insects.com.

Excerpted from The Feral Forager, a self-published zine, available from Wildroots at www.wildroots.org/ff.php. Used by permission.

Recipe: Burdock and Stinging Nettles

My own paradise garden of mutual naturalization has two plants I want to share here: burdock and stinging nettles. Both are Eurasian weeds, introduced species where I live (though there are native stinging nettles species in this region), but they adapt easily and are self-perpetuating with barely any encouragement. And both are delicious seasonal foods with important nourishing and tonifying properties.

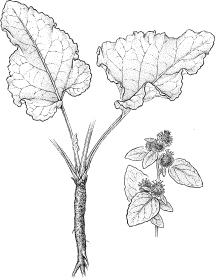

Burdock (Arctium lappa) is one of my favorite plants to eat. The root has a sweet, earthy flavor and crunchy texture that I enjoy raw, fermented, or cooked. Burdock is a biennial, meaning that its life cycle takes two years, and it doesn’t go to seed until the second year. The first-year plants, low to the ground with large, hairy leaves but no tall central stalks yet, have the more tender, delicious, and flavorful roots. Harvest them in the fall or early in the spring to take advantage of the energy they have stored in their roots. Burdock plants typically grow in groups; when I harvest, I always leave at least one plant in each group to grow the second year, go to seed, and perpetuate more burdock.

The distinction between weeds and cultivated plants need not be sharp; a small amount of cultivation can do wonders to encourage a weed you like. I walk around each fall spreading mature burdock seeds—which grow in burrs that stick like Velcro to hair, clothes, pets, and anything else (hence the name burdock)—to create new stands of burdock around our land, especially in marginal, uncultivated areas. Whenever I want to harvest burdock I go to one of these stands with a strong shovel to dig first-year roots.

I like to eat raw burdock root whole, like a carrot, skin and all. Burdock root sliced lengthwise into strips makes a great filling for nori rolls; the root is a common ingredient in Japanese cuisine, in which it is known as gobo. Burdock roots can be shredded into slaws, krauts, and kimchis or sliced (on the diagonal is my favorite) for stir-frying, oven-roasting, boiling into soup stock with other vegetables, or brewing into medicinal teas or herbal elixir meads (see Recipe: Herbal Elixir Mead).

Herbals often refer to burdock as a blood purifier that tonifies the liver and kidneys and is helpful for treating skin ailments such as eczema and psoriasis. “The dynamics of burdock root’s detoxicant functions are interesting,” writes Peter Holmes in The Energetics of Western Herbs. “The root specifically retrieves toxins from the connective tissue and shunts them into the bloodstream.”27

Burdock. ©Bobbi Angell. Used by permission.

Stinging nettles (Urtica dioica) is another common weed that I love to eat and drink. My herbalist friend Judith got me hooked on nettles tea while I still lived in New York. There, I drank dark green infusions of dried nettle leaves that I bought, which tasted like concentrated chlorophyll and left me feeling green and radiant.

When I planted a small patch of nettles a dozen years ago, it was somewhat controversial. Some of the folks I live with worried that the weed would spread and become an invader in our gardens. What makes nettles potentially problematic is that the plant is covered with sharp stingers that leave a tingling sensation in the skin. Seeking to assuage the worries of a nettles invasion, I carefully chose a spot from which the nettles could not easily spread, a marginal space between our barn and the driveway. After a dozen years, the patch has become dense with nettles and has rounded the corner of the barn; however, it has not spread much beyond. Each spring, as new growth emerges from the nettles patch, we give it room by cutting back the dead growth from the year before. This is all the cultivation that the perennial nettles patch requires.

Stinging Nettles. ©Bobbi Angell. Used by permission.

It’s best to harvest nettles in the spring, before the plant goes to seed, which alters its chemical composition. My method is to use scissors to cut the stalks, with a bowl in my other hand to catch the falling stalks and leaves. I mostly avoid touching them, though I find that I can brush against the nettles without being stung as long as I’m careful about moving toward the growing tip, with the stingers; only if I brush past the plant in the opposite direction, against the stingers, do I get stung.

The stings are not so bad. They are quite stimulating, actually, and one traditional way of using nettles as medicine is urtification, or flogging with the plant to deliberately sting an area of the skin and thereby deliver the nettles’ medicine directly to that area. “Urtification creates an intense physical and energetic stimulus to capillaries/circulation, nerves/meridians, muscle fibers, lymphatic flow, and cellular metabolism, combined with multiple surface injections (like a vaccination) of a fluid containing, among other things, histamines, acetylcholine, and formic acid,” writes herbalist Susun Weed.28 People use urtification to treat arthritis, sore muscles, and localized inflammations, as well as recreationally. Regular eating or drinking of nettles nourishes the blood; tonifies the kidneys, lungs, and digestive system; relieves fatigue; helps regulate metabolism and adrenal function; drains fluid congestion; and makes hair strong. “Our doctors and pharmacists are ashamed of fetching such a common weed from behind the fences and including it in their formulas,” wrote the German physician-herbalist Hieronymus Bock in 1532, “even though in both cookery and medicine it has proven its mighty, impressive effects.”29

The nettles’ stingers are deactivated by heat, so I steam nettle leaves before eating them. They are delicious when simply steamed, or they can be added to soups, casseroles, pestos, or pâtés. To infuse nettles into a strong tonic beverage, it is best to dry the leaves first. Harvest the stalks and either hang them from a string or spread them out on a screen in a hot, dry spot out of direct sunlight (which can degrade nutrients). Once they are crisp and dry, you can crush the leaves and store them in a sealed glass jar to use as needed. To infuse, place a handful of nettles in a Mason jar, then pour boiled water over them to fill the jar. Seal the jar and leave it to infuse for several hours, until it cools to room temperature, by which point the contents will be a deep, dark green. Strain out the plant material and enjoy this “green milk,” which can be stored in the refrigerator.

Recycling Used Cooking Oil into Fuel

With the expected coming scarcity of fossil fuels and the ever-escalating costs of securing dwindling petroleum resources, there is much activity around the world focused on creating biofuel alternatives. The most widely used biofuel in the United States currently is ethanol, an alcohol fermented and distilled from corn that is typically mixed with gasoline. Any carbohydrate can be similarly fermented, and projects are under way around the world fermenting abundant carbohydrates into ethanol. Brazil has undertaken an especially ambitious ethanol program, fermenting it from sugarcane. Twenty-five percent ethanol fuel is now standard in Brazil (compared to 2 to 10 percent “gasohol” blends available in some parts of the United States); new cars are now being manufactured in Brazil that can run on 100 percent ethanol, and Brazilians are even exporting ethanol to Asia.

The other major form of automotive biofuel is biodiesel, which can be made from vegetable oil or animal fat. The engines invented by Rudolf Diesel in 1892 were originally conceptualized as having the flexibility to run on virtually any fuel, including whale oil and vegetable oils. “Motive power can be produced by the agricultural transformation of the heat of the sun,” Diesel said.30 George Washington Carver experimented with peanut oil in diesel engines, but until recently there was little exploration of biofuels for diesel engines, mostly because petroleum-based fuels were so cheap, and refiners could sell one of their byproducts as diesel fuel. But shifting economic and environmental realities since the 1970s have spurred interest in biodiesel research, and today biodiesel is being produced from many different “feedstocks,” most prominently rapeseed (canola, used widely in Europe), sunflower, soybean (the favorite in the United States), and palm oils.

Biofuel production is great, and I’m glad government and industry are directing resources to alternative fuels. Many big vehicle fleets are running on biodiesel blends, including some in the military, the postal service, school districts, and municipalities. Minnesota became the first state to require that biodiesel be blended into all diesel fuel sold there, at a 2 percent level (marketed as “B2”), and the federal government has begun offering tax incentives to encourage more biodiesel blends. “Biodiesel has buzz,” observes North Carolina biodiesel activist Lyle Estill:

In the commercial fuel sector it has buzz as a lubricity additive to petroleum diesel. In the clean air crowd it has buzz for its reduced emissions. In agricultural circles it is talked about as a new cash crop. Academia is excited because biodiesel is a frontier, full of unknowns. There is plenty of ground-breaking research still to be done on how to make fuel from soy or algae or flies that feed on hog waste. Biodiesel has buzz with the peaceniks because there is “No War Required” to obtain it. It has traction with those on the Right side of the political spectrum because it can be “Made in America.”31

But fuel from soybeans and corn and sugarcane also means more monoculture, more genetically modified acreage, and more agrochemicals. In their institutionalized forms, biofuels really aren’t especially eco-friendly at all, and they mostly benefit large corporate grain processors, most prominently Archer Daniels Midland.

Biofuels, like anything in mass production, are far removed from our daily experience, in the same abstract netherworld as petroleum itself—or for that matter food or any of the conveniences of our consumer society. And since we started this chapter with a discussion of hunger, with millions starving and food scarcity the dominant paradigm, how can we justify using precious food resources for fuel? “Definitely there is a danger that the competition can hit food security and food availability,” worries Gustavo Best of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization.32 Biofuels are an alternative to petroleum, not a panacea.

One form of biofuel is especially exciting because it does not require redirecting any edible food or agricultural resources. Biodiesel activists around the world are collecting a messy, smelly, difficult-to-dispose-of, abundant waste material—used fry oil, of which U.S. food industries produce more than three billion gallons per year33—and converting it into fuel. Community biodiesel operations recycling used cooking oil are shining examples of sustainability. This grassroots network is rapidly expanding and inspiring me and many others to want to become part of it.

Fry oil, or any feedstock oil, requires a bit of processing to turn it into biodiesel, specifically a chemical reaction called transesterification, which separates the viscous glycerin from the oil, enabling it flow at cooler temperatures. To accomplish this, wood alcohol (methanol) and a chemical catalyst (lye or caustic soda) are mixed together into methoxide and then added to the oil. The oil is a triglyceride—three fatty-acid chains joined with glycerine. The alcohol joins with the fatty-acid chains to form alkyl esters (biodiesel), freeing the glycerin, which is responsible for the viscosity of the oil. The glycerin, which separates out, becomes a by-product of the process that can be composted and has many potential applications as yet to be fully developed.

Diesel engines can also run on straight vegetable oil (SVO), once solid particles are filtered out and any water is removed; however, for the viscous vegetable oil to flow and combust steadily, it must be warm. So typically people who run on SVO convert their engines to dual-tank fuel systems, using a more refined fuel (biodiesel or petroleum diesel) to warm the SVO before switching to SVO as the fuel source, and then switching back a few minutes before stopping, so the fuel lines don’t get clogged when they cool down. These are hassles that most people prefer not to have to worry about. Running on processed biodiesel generally requires only minor changes to the automobile.

People in many different places are learning how to process waste cooking oil into biodiesel. It involves a bit of chemistry and a bit of plumbing, and many impassioned activists are totally geeking out on this accessible and appropriate technology. Maria “Mark” Alovert is one of the do-it-yourself biodiesel pioneers; she has designed many backyard setups, has traveled widely teaching workshops, and has written and self-published the Biodiesel Homebrew Guide as well as many articles posted online on the finer points of small-scale biodiesel production. She is not alone; free exchange of information has characterized the grassroots biodiesel movement. Reflects Mark, “Due to the rise of infosharing on the Internet, there has been, in the last seven to eight years, a boom in the number of people making their own biodiesel, experimenting with equipment and techniques, and sharing their experiences over Internet forums and Web sites.”34 Collectives or co-ops of various shapes and sizes recycling local waste oil into fuel have sprouted up in communities around the world, and the movement is spreading fast.

Lyle Estill, one of the founders of Piedmont Biofuels, a 150-member biodiesel co-op in Pittsboro, North Carolina, made his first batch of biodiesel in 2002 after he first learned of the existence of this technology, tried to locate some to buy, and discovered that it was not commercially available in his state. He and a friend made that first batch in a blender, following the directions in Joshua Tickell’s book From the Fryer to the Fuel Tank. “Anyone can make biodiesel in a blender,” says Lyle. “The problem is scaling up the process to make more meaningful quantities of fuel.”35

As he pondered this problem, Lyle spotted a flyer hanging on a bulletin board in a local café, with a headline inquiring, “Think Fuel from Vegetable Oil Is Impossible?” The flyer advertised a course on biofuels at nearby Central Carolina Community College, in which Lyle promptly enrolled. The course was taught by two instructors, Rachel Burton and Leif Forer, who had limited experience but great enthusiasm. “What intrigued me was that these two were about to embark on the creation of a large-scale biodiesel processor and were willing to take the class with them,” recounts Lyle. “Lack of knowledge, experience, or resources did not dampen their spirits a bit.”36

Three years later, when I visited Piedmont Biofuels in 2005, their first experiments had morphed into a thriving co-op providing fuel to 150 members. Members can pump ready-made 100 percent biodiesel (referred to as “B100”) at five different pumping locations or use shared equipment for do-it-yourself production. And the co-op is in the midst of expanding its scale, recycling an abandoned chemical plant into a biodiesel factory capable of turning out twenty thousand gallons of biodiesel a week, for a million gallons a year. The Piedmont Biofuels activists are at the forefront of the biodiesel revolution, empowering themselves and others with simple creative technology, tapping into a huge waste stream, and producing fuel for people in their community.

Automotive power is not the only way that fry oil can be recycled as fuel. A Boston-area restaurant, Deluxe Town Diner in Watertown, Massachusetts, is reusing the thirty to forty gallons of vegetable oil it goes through each week in its fryers to heat the restaurant. “Why should we drain the planet’s resources by burning up expensive heating oil when we have our own supply of oil right here in the restaurant?” asks owner Don Levy.37

I’m inspired, and I want to help recycle used fry oil into fuel where I live. As this book has been in production, I’ve been working with a group of friends to start processing biodiesel here on our land. We’ve been assembling materials, collecting used oil from local restaurants, visiting other biodiesel processing operations, reading, and asking lots of questions. This movement is spread by nuts-and-bolts skillsharing. By the time you’re reading this, I expect to be one of several folks around here driving around on biodiesel, spewing exhaust that smells like doughnuts.

Composting and Humanure

No discussion of rescuing food from the waste stream would be complete without some reference to compost. Composting is the ultimate (and the original) recycling process. It is an everyday miracle, a beautiful metamorphosis to witness, and an indispensable link in the ongoing cycle of life and death and fermentation. J. I. Rodale’s Encyclopedia of Organic Gardening, like many accounts, waxes poetic: “In the soft, warm bosom of a decaying compost heap, a transformation from life to death and back again is taking place.”38 This transformation is the basis of soil fertility and an obvious strategy for dealing with food waste.

Food comprises an estimated 12 to 16 percent of U.S. waste, according to various estimates.39 What is shocking to me is that more of this waste stream is not diverted at the source, before it becomes waste, into compost, which would quickly transform it into a valuable resource. Instead it becomes a burden, piling up in landfills, being incinerated into air pollution, or floating on trash barges in the sea, with no clear destination.

For urban dwellers without any land, composting may seem impossible. When we lived in a fourteenth-story apartment in New York City, my roommates and I tried an enclosed anaerobic (oxygen-free) composting system in a covered plastic garbage container in our apartment. What a disaster! We learned that anaerobic composting stinks. Composters generally seek to create conditions that favor aerobic bacteria. After we finally acknowledged what a disgusting, smelly mess it was, we had to somehow get rid of it. We snuck the hefty anaerobic stink bomb out of the building in the middle of the night, lugged it a block away, and left it in a construction dumpster. Later, when I moved downtown where there was more of a community gardening scene, I would walk my food scraps ten blocks to add them to a garden’s compost pile. It was important to me, as a gesture.

You can choose whether you generate waste or appropriately channel resources. Compost is an important effort to make if you seek to minimize waste and contribute materially to the cycle of life. You can find a garden with a compost pile you can add to, or, with even just a tiny bit of outdoor space, a balcony, or roof access, you can compost in stacked milk crates. Alternate layers of kitchen scraps with layers of grass cuttings, leaves, or other dry plant material as you fill the crate. After you fill a crate pile another on top of it; remove finished compost from the bottom. Worm-bin coffee tables are another strategy for apartment composting, according to Cleo Woelfle-Erskine, editor of Urban Wilds: Gardeners’ Stories of the Struggle for Land and Justice.40

Some people go out and collect organic waste to compost. Heather Flores, founder of Food Not Lawns, reports that in her hometown of Eugene, Oregon, “we cruise the back doors of the stores and cafés in town and pick up their vegetable waste for compost piles.”41 In Nashville, Tennessee, a community gardening group called Earth Matters organizes an annual “Leaf-Lift,” collecting homeowners’ bagged fallen leaves in autumn and composting them, along with food scraps and other organic wastes, in massive sculptural forms.

A few forward-looking cities, first in Europe in the 1990s, and now in the United States, have begun municipal programs for composting food scraps. San Francisco distributes green plastic “biobins” in which households and businesses can collect food scraps; haulers collect the scraps on a designated schedule and bring them to commercial composting operations outside the city. The mature compost is sold as fertilizer to northern California vineyards and marketed as “Four-Course Compost.” The program has reduced municipal landfill input by 19 percent; it has expanded into the East Bay, and activists in other cities are promoting similar models.42 Even if we can’t convince local policymakers to embrace composting, we all can find ways of composting our own scraps and encourage our friends to join us. Composting recycles: it recovers the food as a resource and rescues it from the fate of becoming a burden, part of the waste stream.

When we examine the waste stream in its entirety, another huge share of it is food in its postdigested state: excrement. Manure need not be treated as waste. Many types of animal manure have been used to heat and generate energy, and just like food scraps, manure can be rapidly transformed into soil-building humus through composting. “One organism’s excrement is another’s food,” observes Joseph Jenkins, the author of the cult classic The Humanure Handbook. “Everything is recycled in natural systems, thereby eliminating waste.”43

We humans each produce an average of about three hundred pounds of shit per year.44 In our contemporary culture, we treat shit as unspeakable and flush it away to make it disappear instantly. Personally, I like to talk about shit. When I feel completely reborn by a particularly satisfying movement, I like to share my enthusiasm. If a friend is sick and experiencing changes in shit texture or consistency, I like to hear about that, too. For me it’s about claiming the body and all its functions without shame. I also like to talk about sex and symptoms of illness, and I even enjoy the odors that bodies give off. What is the benefit of pretending our bodies do not do these things? Who do we think we are fooling? It is a manifestation of the same disconnection from the earth that has happened with our food. We must face our shit, embrace our bodies, and feel our connection to the earth.

In our effort make our excrement disappear, we create huge problems. Each time we flush away our poop or piss, with it go an average of 3.3 gallons of water per flush, and each of us flushes an average of 5.2 times a day.45 Our daily flushes alone consume more water than the total daily water supply in many regions of the world. The typical person in the United States flushes 6,263 gallons of potable water down the toilet each year, adding up to 1.75 trillion gallons per year for the United States as a whole. “We defecate into water, usually purified drinking water,” writes Joseph Jenkins. “After polluting the water with our excrement, we flush the polluted water ‘away,’ meaning we probably don’t know where it goes, nor do we care.”46 Wherever it goes, those gallons of water are now sewer-flavored, shit and piss and other bodily fluids mixed with detergents and paints and solvents and whatever else gets poured down drains and storm sewer systems. Reclaiming that water requires the use of more chemicals and elaborate, expensive processing. “The solution is to stop fouling our water,” writes Jenkins, “not to find new ways to clean it up.”47 (For more on water activism, see chapter 10.)

Historically people have recycled their excrement into soil by various techniques, some very successful at eliminating pathogens, others less so. The Humanure Handbook explains in simple terms techniques for thermophilic (high-temperature) composting of humanure, in which a mix of feces, sawdust, grass clippings, and vegetable scraps encourage heat-generating organisms to do their thing and thereby kill intestinal pathogens and quickly break the materials down into rich humus. Observes Jenkins: “Humanure, unlike human waste, is not waste at all—it is an organic resource material rich in soil nutrients. Humanure originated from the soil and can be quite readily returned to the soil.”48

In some parts of the United States extremely rigid regulations prohibit the use of composting toilets. Friends of mine with land in Vermont, where they camp and host group events, have been forced to rent portable chemical toilets rather than create composting toilet systems. The fear behind regulations like this is that human excrement not composted correctly has the potential to pollute groundwater. “A review of composting toilet laws is both interesting and disconcerting,” notes Jenkins, citing nonsensical, almost superstitious laws, “apparently written by people who are either lacking in knowledge and understanding, or are fecophobic, or, most likely, all of the above.”49 Jenkins advises:

When researching the laws, look into those that regulate backyard composting (if any), because that’s what you’re doing. . . . It’s not sewage disposal, garbage disposal, or plumbing, or anything like that. If you look into those laws you may become overwhelmed and confused.50

As with any legal question, Jenkins says, “the semantics are important and not trivial.”

Each of us has a choice as to whether to treat this daily production of our bodies as toxic waste or as a resource. At the community where I live we have no sewage hookup, no septic system, no porta-potties, just outhouses and pits in the ground. We compost all our shit. As each deposit is made, it is covered with sawdust. Twice a year we empty our central four-seater and leave the partially composted excrement in a huge pile for a year to break down. Then we use it to fertilize our fruit trees.

Emptying the shitter is a humbling experience, an hour of digging in deep shit and hauling it in wheelbarrows. What amazes me every time is how quickly the shit breaks down. The top layer is still recognizable as shit, but once you get below the surface to the stuff that’s begun to decompose, the shit and other materials become one, transformed into worm-rich humus with no visual or olfactory likeness to shit.

Reduce, reuse, recycle. Live this ethic fully. Eat it, wear it, drive it, live in it, create it. Become more connected to the cycles of life and encourage other people to join you. Extricate yourself from constant convenience consumerism and strive to eliminate waste. Make scavenging, foraging, and recycling a way of life.

Action and Information Resources

Books

Alovert, Maria “Mark.” Biodiesel Homebrew Guide. 10th ed. Self-published, 2005. Available online at www.localb100.com.

Brill, Steve. Identifying and Harvesting Edible and Medicinal Plants in Wild (and Not So Wild) Places. New York: Harper, 1994

Butler, C. T. Lawrence, and Keith McHenry. Food Not Bombs. Tucson, AZ: See Sharp Press, 2000.

DeFoliart, Gene R. The Human Use of Insects as a Food Resource: A Bibliographic Account in Progress. Self-published, 2003. Available online at www.food-insects.com.

Diamond, Jared. Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. New York: W. W. Norton, 1999.

Estill, Lyle. Biodiesel Power: The Passion, the People, and the Politics of the Next Renewable Fuel. Gabriola Island, BC: New Society, 2005.

Flores, Heather C. Food Not Lawns: How to Turn Your Lawn into a Garden and Your Neighborhood into a Community. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green, 2006.

Gibbons, Euell. Stalking the Healthful Herbs. Chambersburg, PA: Alan C. Hood, 1966.

———. Stalking the Wild Asparagus. Chambersburg, PA: Alan C. Hood, 1962.

Gordon, David George. The Eat-a-Bug Cookbook. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press, 1998.

Handerson, Robert K. The Neighborhood Forager: A Guide for the Wild Food Gourmet. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green, 2000.

Hart, Robert. Forest Gardening: Cultivating an Edible Landscape. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green, 1996.

Hoffman, John. The Art and Science of Dumpster Diving. Port Townsend, WA: Loompanics, 1993.

Jacke, Dave, with Eric Toensmeier. Edible Forest Gardens. 2 vols. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green, 2005.

Jenkins, Joseph. The Humanure Handbook. 3rd ed. Grove City, PA: Joseph Jenkins, 2005.

Johnson, Lorraine, and Mark Cullen. Real Dirt: The Complete Guide to Backyard, Balcony & Apartment Composting. Toronto: Penguin Books of Canada, 1992.

Lappé, Frances Moore, and Joseph Collins, with Cary Fowler. Food First: Beyond the Myth of Scarcity. New York: Ballantine, 1977.

Lappé, Frances Moore, Joseph Collins, and David Kinley. Aid as Obstacle: Twenty Questions about Our Foreign Aid and the Hungry. San Francisco: Food First, 1980.

Luddite, Laurel, and Skunkly Munkly. Fire and Ice. Apeshit Press, 2004.

Menzel, Peter, and Faith D’Aluisio. Man Eating Bugs: The Art and Science of Eating Insects. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press, 1998.

Muskat, Alan. Wild Mushrooms: A Taste of Enchantment. 4th ed. Asheville, NC: self-published, 2004. Available online at www.alanmuskat.com.

Niehaus, Theodore F. A Field Guide to Pacific States Wildflowers. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1998.

Pahl, Greg. Biodiesel: Growing a New Energy Economy. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green, 2005.

Peterson, Lee Allen. A Field Guide to Edible Wild Plants: Eastern and Central North America. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1999.

Tickell, Joshua. Biodiesel America: How to Achieve Energy Security, Free America from Middle-East Oil Dependence and Make Money Growing Fuel. Tallahassee, FL: Tickell Energy Consulting, 2006.

———. From the Fryer to the Fuel Tank. Tallahassee, FL: Tickell Energy Consulting, 2000.

Weed, Susun S. Wise Woman Herbal: Healing Wise. Woodstock, NY: Ash Tree, 1989.

Periodicals

Food Insects Newsletter

333 Leon Johnson Hall

Montana State University

Bozeman, MT 59717-0302

www.hollowtop.com/finl_html/finl.html

Biodiesel Cyberinformation

Collaborative Biodiesel Tutorial

Journey to Forever Online Biofuels Library

www.journeytoforever.org/biofuel_library.html

LocalB100.com

Films

Fat of the Land. Lardcar, 1995; www.lardcar.com.

The Gleaners and I. Directed by Agnès Varda. Zeitgeist Films, 2001; www.zeitgeistfilms.com.

Organizations and Other Resources

Big Box Reuse

Food Not Bombs

PO Box 744

Tucson, AZ 85702

(520) 770-0575

Food Not Lawns

31139 Lanes Turn Road

Coburg, OR 97408

Joe Hollis

Mountain Gardens

Shuford Creek Road

Burnsville, NC 28714

(828) 675-5664

International Food Policy Research Institute

2033 K Street NW

Washington, DC 20006-1002

(202) 862-5600

Piedmont Biofuels

PO Box 661

Pittsboro, NC 27312

(919) 321-8260

Sequatchie Valley Institute/Moonshadow

1233 Cartwright Loop

Whitwell, TN 37397

(423) 949-5922

Wildroots Collective

PO Box 1485

Asheville, NC 28801

(866) 460-2945