1

The Scope of Rural Environmental Planning

RURAL ENVIRONMENTAL PLANNING (REP) is a community process to determine, develop, and implement creative plans for small communities and rural areas. The goal of the REP process is to establish sustainable rural communities by balancing economic development and environmental protection in accord with the carrying capacity of the land. REP treats conservation of the natural environment and development of the human community as equally important. REP develops people to plan and develops plans for people.

Rural, in this context, means open or sparsely populated areas as well as villages, small towns, Indian pueblos, and other tribal communities. Environmental is used here in its broadest sense, meaning all the surroundings, including social, cultural, physical, and economic. Planning involves people in the process of assessing needs, inventorying resources, formulating goals, drafting and testing a plan, and then adjusting that plan over time. The written plan is the map, not the destination. The intent of REP is to develop the ability of rural residents to manage a sustainable environment, a viable community economy, and other aspects that make up the rural ecosystem.

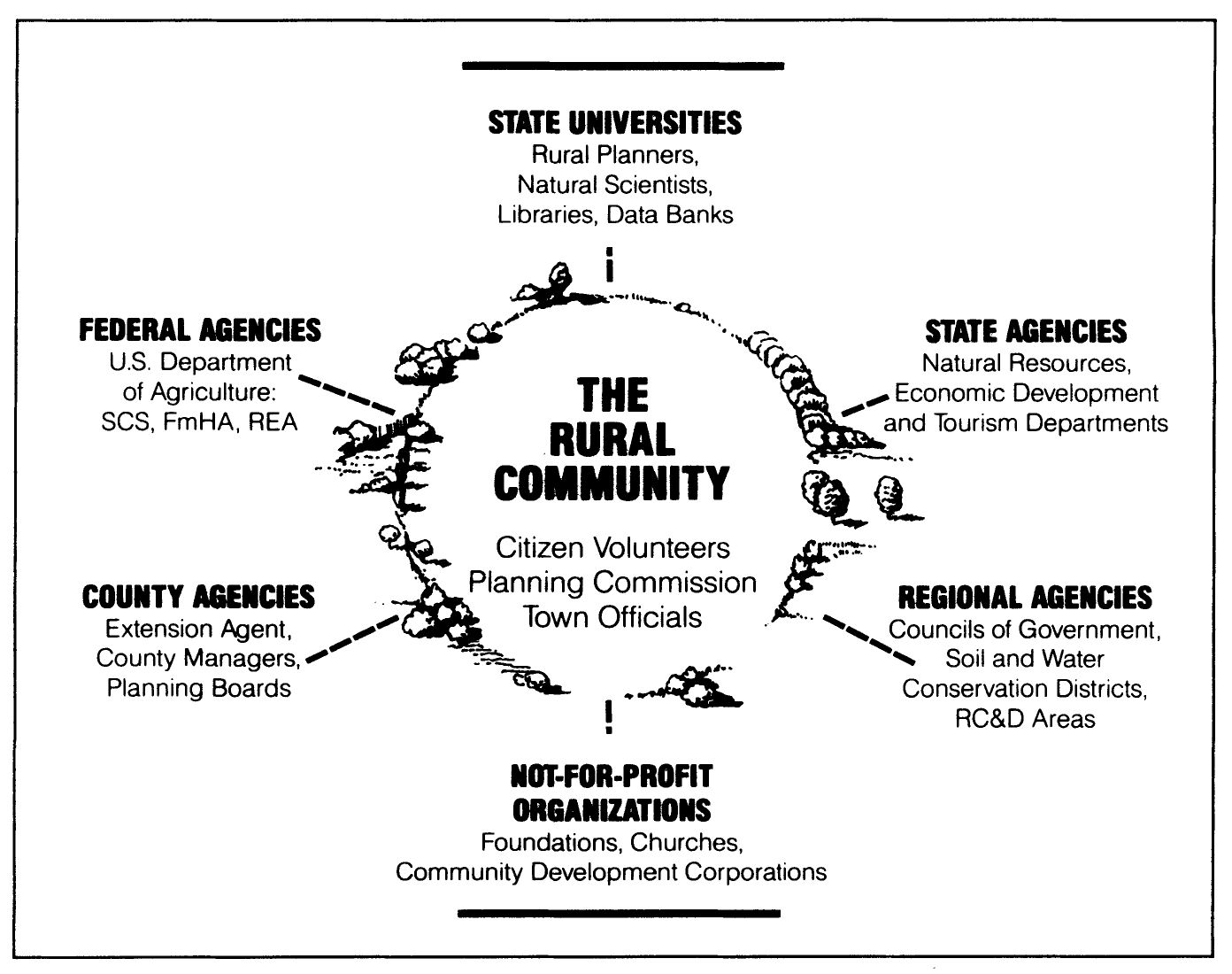

This book considers the rural community as the center, the providers of planning and development services as a supporting ring. Local citizens determine community goals; educational institutions lend the services of environmental planners and student assistants to coordinate REP; selective teams from public and volunteer agencies contribute technical data, analysis, and preliminary recommendations.

REP is a partnership among three participants: the client, the planner, and the technical team. The client can be a single unincorporated community, a political jurisdiction such as a village, town, or county, or an Indian pueblo or tribe. It also can be a multiple-jurisdiction area such as a watershed, a cluster of mountain villages, or any other geographic area where people have a common interest in the sustainable use of shared resources. The planner is the organizer, coordinator, and facilitator of REP. The role of rural environmental planner may be filled by a faculty member, a graduate student, a recent graduate of rural planning at a state university, a rural-planning specialist with a state planning or economic development agency, or a qualified professional engaged by residents of the community.

FIGURE 1.1. The Rural Environmental Planning Process: Sources of Planning and Development Assistance

Technical teams are people who have the expertise to assist the community during various stages of inventorying, planning, and implementation. Team members supply data, analysis, and preliminary recommendations. These technically skilled experts may come from a state university, state or federal agencies, not-for-profit organizations, or professionals from the private sector. What is important to the REP process is that the technical team and the rural residents form a partnership of mutual learning. In the transfer of knowledge and skills, each learns from the other. REP allows for the time it takes for this relationship to grow. The confidence that develops from successful interaction between community members and the technical team cannot be reproduced by one or two meetings, workshops, or information sessions. Rather, confidence is built over time by successes that result from the REP process.

Some critics of REP say the approach is value-loaded and biased. Nothing could be closer to the truth. The assumptions and values behind REP are as follows:

- Rural people place a high value on self-reliance and self-determination. They have experience with techniques for cultural and economic survival. They can make decisions regarding their long-term interests, design and carry out programs, evaluate the results of their work, and make necessary adjustments.

- Rural people value cooperation as a guide to problem-solving. This attitude has evolved from generations of experience in rural living, where cooperation is a major tool of survival and community maintenance.

- Long-term sustainability of a rural environment is achieved when citizens guide economic development according to the “physical carrying capacities” of the ecosystem. Land ownership is valued not just for its market value but also for sustaining a way of life. Consideration of the ecosystem’s physical carrying capacity assumes that, although efficiency of use can vary, physical and natural resources are finite and can bear only so much use.

- Increasing the self-reliance of citizens in rural communities can be the basis for sustainability. A self-reliant community possesses the knowledge, skills, resources, and vision to identify changing conditions, locate appropriate technical assistance, and initiate actions in a manner that conserves the rural environment and distributes benefits in an equitable manner.

In planning for rural self-reliance, human, animal, and plant ecologies are understood as the prime interdependent system. The rural community is seen as the conservator of its own resources, habitat, and culture. Local citizens are directly involved in the control of community assets as they plan for the retention, enrichment, and equitable use of those assets for present and future generations.

Conventional large-scale urban planning assumes that growth is inevitable and desirable, that increasing the tax base is a prime concern, and that authorities setting public goals are the planners and municipal administrators. REP employs a more democratic method of determining public goals: people are asked what they want. REP helps people to evaluate what they have, to envision choices for the future, and then to realize that they have the competence and the responsibility to act on those choices. REP results in new and sometimes alternative public goals, often very different from traditional goals.

REP is an open planning process. This means it involves as many citizens as possible in each step of planning and decision-making. As described in chapter 3, citizens define goals and make choices, take field trips to study existing conditions and land uses, hold public meetings to determine preferences and priorities for resource access, development, and protection, and so on. The involvement of local citizens in an open and democratic planning process helps to shape a plan in their minds as well as on paper and thus enhances the prospect that the plan will be implemented.

REP should not be confused with regional planning. Regional planning—a long-established subdiscipline of planning—addresses regions with urban centers or very large geographical land areas such as whole river basins or clusters of counties within a state. In traditional large-scale urban planning, the first step is often a projection of population growth, proposed commercial and industrial growth, jobs needed, housing needed, and the public facilities and transportation networks to serve all this. Land-use maps are prepared and colored yellow, red, blue, purple, and gray to allocate these projected needs. Land left over is colored green and labeled “open space.” Open space may include cemeteries, wasteland, or other land that cannot be developed. In REP, the approach is the opposite. First, lands to support agriculture, recreation, wildlife, and soil and water conservation, as well as natural areas such as mountains, mesas, river valleys, and wetlands, are identified, classified, and mapped in multiple shades and patterns of green. Lands left over are colored red or yellow and designated for intensive uses: residential, commercial, and industrial.

REP also differs from conventional urban planning in the methods it employs for determining and developing public goals, in projecting future land-use needs, in the concepts and techniques it uses for implementation, and in the relevance it has to citizens of rural communities. This book, in fact, is intended for use by citizens in rural areas as well as by professional planners and technicians.

COMPONENTS OF REP

Rural Environmental Planning is defined by listing its significant components. The first three chapters in REP, Part I, describe the basis for planning rural environments and how this process differs from, yet complements, urban and regional planning. The basic concepts and the scope of Rural Environmental Planning are defined in chapter 1. The history of planning for rural settlements and an update on recent perspectives are described in chapter 2. How to get started, the role of jurisdictions, and steps in creating and implementing a plan are discussed in chapter 3.

Eight components of REP are defined in Part II. The discovery and development of community goals are discussed in chapter 4. The purpose and process of inventorying resources are detailed in chapter 5. Methods of classifying and protecting natural areas are described in chapter 6, while chapter 7 lists ways and gives examples of keeping land in agriculture. Chapters 8 and 9 present methods and examples of planning lake and river basins. How to plan for rural character, recreation, and historic preservation are described in chapter 10. Chapter 11 expresses the concern for equity and plan evaluation.

Part III focuses on guiding the process of rural development. Ways to assess economic options and examples of growth management are described in chapter 12. Elements, examples, and a case study of sustainable economic development are presented in chapters 13 and 14. The legal framework of planning and relevant case examples are presented in chapter 15.

The chapters that follow provide detailed methods and examples of REP. Because of their special importance, several issues taken up in detail later are emphasized here: economic development using local resources, diversity and equity as the basis for sustainable growth, the protection of natural areas and the preservation of wildlife habitats, the maintenance of agricultural land, conservation zoning, public access to public waters, water-quality improvement, provision for rural recreation, and planning for “rural quality.”

In REP, economic development using local resources is the foundation for guiding growth. Development should be consistent with land capacities and community goals. A rural environmental plan requires the protection of natural cycles if economic growth is to be sustained. For instance, instead of draining and filling a marsh for an industrial site, the marsh is evaluated as a flood-reduction sponge or wildlife habitat. The industry is located not on the cheapest land but where long-term costs for the entire community are the lowest.

In REP, economic growth can be a major goal only when it is compatible with environmental well being. REP is based on the assumption that if the quality of the environment is maintained, land values will actually increase. The most profitable use of the land can be developed in concert with the best environmental and social uses. In chapter 2 the history and evolution of these concepts and new dimensions are described. The definition of the elements of sustainable economic development and their application are presented in chapter 13. Chapter 14 then describes an expanded case study incorporating each of the elements.

The notion of diversity and equity as the basis for economic growth recognizes that increasing the number and variety of income sources can help rural residents to guide economic growth in balance with environmental objectives. From the outset, a rural environmental plan identifies and incorporates the public interest. Growth is permitted in accordance with the ability of the local jurisdiction to supply public services, to build and maintain roads and schools, to retain the rural character, and to protect historic sites and cultural resources. In the REP process we assume that the whole public, not just a favored few, should participate in planning and have access to the quality environment that is its end. Methods to achieve a more sustainable, resilient, and equitable economy are discussed in chapters 11, 12, 13, and 14.

The protection of natural areas and the preservation of wildlife habitats are readily appreciated by rural residents. A natural area is any area that concerned citizens (those affected) say should be protected and maintained in its natural state for present and future public use. This definition is vague because each area is unique. Examples of natural areas include mountain summits, caves, mesas, waterfalls, river floodways and marshes, virgin timber stands, habitats for unusual species, unique or representative geological formulations, and other natural phenomena with ecological significance. In REP, wildlife habitats are identified, located, and evaluated. Their protection is especially appropriate in areas that are unsuitable for development because of water conditions or topography. Techniques for identifying and inventorying these unique resources are presented in chapter 5. Techniques for protecting these areas and enhancing their performance are described in chapter 6.

The maintenance of agricultural land and the reduction of pressure for changing these lands to intensive urban use are mutually supportive goals in REP. Specific methods of accomplishing these goals—without depriving landowners of legal rights, without reducing the value of land accumulated or inherited over generations, and without significant cost to the community—are detailed in Chapter 7 and illustrated with case studies.

The concept of conservation, that is, the prudent and sustainable use of natural resources, is generally accepted as desirable by town officials, residents, and landowners in rural jurisdictions. Protecting these resources through conservation zoning, however, may encounter resistance from some rural residents. This book will propose strategies for identifying and conserving areas in order to protect water quality, prevent soil erosion, and achieve other community objectives. Such areas include steep slopes, stream banks, floodplains, arroyos, groundwater recharge areas, wetlands, and high elevations. Conservation designations or zones, when applied to areas unsuitable for development, do not have to deprive rural landowners of inherent land rights. In fact, conservation zones may enhance land values by guaranteeing wise land use in the area. Knowledgeable landowners understand this potential. Principles and examples of conservation zoning are described in chapters 5, 6, 7, and 10.

Public access to public waters is another concept important to people in rural areas. Typically, rural areas or towns with extensive frontage on public rivers, streams, or lakes have little or no public access. While exploring public goals, participants can promote awareness of the notion that public waters are owned by the community, that the public has a right to multipurpose access, and that such access is both feasible and appropriate. Methods for providing significant access to public lakes, streams, and rivers are described in chapters 8 and 9.

Water-quality improvement is a major thrust of REP in both humid and arid environments. Bodies of water including underground springs have often been used as dumping places for sewage and toxic waste. When people became concerned about water quality, they delegated the task of improving it to a state or federal agency. In REP, water supply and quality are looked upon as the prime public health, recreation, aesthetic, and economic resource of a rural area or town. Chapter 9 describes methods and examples of water quality planning.

Provision for recreation is indispensable for a quality rural environment. Traditionally, residents in rural New England could go anywhere in the jurisdiction of their town to hunt, fish, study nature, collect, think, hike, walk, climb, ski, or just sit. If the resident came across a No Trespassing sign, he or she knew it did not apply to local folk. This freedom of movement is being lost as rural areas undergo incremental urbanization with its attendant posting of trespassing signs. With the growth of metropolitan areas and the expansion of communication and transportation networks in all parts of the United States and Canada, the open countryside has largely fallen into private hands, resulting in limited public access. As an example, for many centuries in the Southwest, large parcels of open land were held in common by Indian, Spanish and Mexican settlers. Land grants were not deeded for private land until the application of English law and custom in the mid-1880s. To counter these trends and recapture freedom of movement outdoors, it is necessary to address the subject of common lands directly in a rural plan. Specific techniques to address rural recreation, trail networks, conservation zones, and related issues are detailed in Chapter 10.

Planning for rural quality is a conceptual and functional breakthrough of REP. People often say, “You can’t plan aesthetics.” However, there has been sufficient general agreement concerning aesthetic value to make planning for the character and quality of a rural community the least controversial section of most rural environmental plans. Most people concur that unscreened auto graveyards and billboards are ugly, and that trees, grass, flowers, and mountain views are beautiful. A plan may include landscaped areas in commercial zones, scenic overlooks or picnic areas, rigorous sign control, tree-cutting controls, and reforestation programs. It also may include the identification and preservation of “sacred places” such as the town plaza, a historic building, or a mountaintop. Chapter 10 describes approaches to and gives examples of planning for rural character, a sense of place and historic preservation.

CASE: CHAMA, NEW MEXICO

REP is applicable to diverse physical and cultural settings. For example, in 1980 a rural environmental plan was developed by the citizens of the village of Chama, New Mexico (1980 population 1,090), and its surrounding area (population 2,022).1 The plan addressed areawide resource use and economic development to complement a 1973 master plan defining village services and capital improvements. While the REP process was supported by a grant from the Farmers Home Administration under the sponsorship of the Chama village council, and while rural planning students from the University of New Mexico contributed much of the technical work, it was mostly volunteer and nonprofit community organizations that implemented the plan’s key components. Sections of the plan calling for valleywide coordination of health and social services were implemented by the community-owned and operated La Clinica del Pueblo. Sections calling for economic development based on agricultural and human resources were implemented by an agro-economic development corporation, Ganados del Valle. Inventorying human resources in the Chama Plan is described more fully in Chapter 5; economic development aspects are presented in Chapter 14.

CASE: SAN YSIDRO, NEW MEXICO

Then there is the example of the village of San Ysidro de los Dolores, New Mexico (population 198), which initiated a rural environmental plan in 1985. This predominantly Hispanic village has existed for almost two hundred years. The recent impact of increasing traffic flow, highway widening, and population growth prompted the citizens to seek help in identifying their resources and defining their goals. With the assistance of graduate students in the community and regional planning program at the University of New Mexico, a survey of every village household brought forth a clear idea of what the community wanted for the future. The survey helped to identify goals regarding local employment opportunities, outmigration, travel outside the valley, water quantity and quality, and growth.2 The process of surveying goals in San Ysidro is described in chapter 4.

CASE: ESSEX, VERMONT

The following example is presented in greater detail because it illustrates well the initiation, evolution, and implementation of a rural environmental plan. It also shows how such a plan, developed by the people of an area rather than for them, can continue to affect community decisions for many years. In 1970 the village of Essex Junction, Vermont, and the surrounding town of Essex faced unprecedented growth. An IBM plant had been located in the village in 1957 and had undergone expansion in 1965. Recognizing the need for planning, and taking advantage of a federal “701” planning-assistance grant, the village and town engaged a planning firm active in the region to provide a comprehensive plan. The town plan, completed in 1967, was a typical municipal plan. It primarily addressed the built-up areas and those areas slated for development in the near future. It designated some areas of the town as open space and stressed the importance of preserving them but provided few details concerning their future use or management. The comprehensive plan was updated by the same firm in 1970.

During this period, the IBM expansion had brought many new residents to the area. They became concerned about the problems resulting from poorly planned growth and started to look into ways of improving prospects for future development. At planning commission meetings, they learned that the principle means of maintaining open space was large-lot zoning. Clustering and other methods familiar to some of the newer residents were not being considered.

At this time the University of Vermont, with the assistance of the Department of Agriculture’s Soil Conservation Service (SCS), had designated REP technical teams to assist towns upon request. One of the new residents, Ann Harroun, and her colleagues called upon a technical team for assistance. A meeting held with the team resulted in the appointment by the Essex and Essex Junction planning commissions of a joint village-town natural resources subcommittee of twenty residents. The subcommittee was assisted by the Chittenden County technical team. This team consisted of six members: an SCS representative, the county forester, a University of Vermont rural planner, a university extension-area development specialist, a cartographer from the Chittenden County Regional Planning Commission, and a university resource economist. They in turn were assisted by three experts from the state departments of water resources, recreation, and forests and parks.

The village and town REP committee met again with the technical team to organize subcommittees and divide the workload. The technical team wrote reports on geology, soils, water resources, and wildlife. The subcommittees, with technical assistance, conducted inventories and wrote reports on historic sites, conservation and recreation areas, neighborhood parks, trail systems, and scenic vistas.

A few months and many meetings and field trips later, the subcommittees and technical team produced a document entitled “Proposal for a Quality Environment, Essex, Vt.”3 It carried seventy-six recommendations, eighteen maps, and an appendix reporting the results of a survey of local attitudes. The proposed plan was presented to the village and town select board and planning commissions as a draft for use in preparing a “quality-environment supplement to their master plan.” Copies were supplied to libraries and to participants. The planning commissions were pleased with the plan, but they did not recommend to the select board that it be adopted. Members of the select board did not adopt the plan; they did, however, together with the planning commissions, consider its recommendations. These were gradually implemented in the course of revising zoning and subdivision regulations, approving developments, and so forth.

THE INDIAN BROOK RESERVOIR

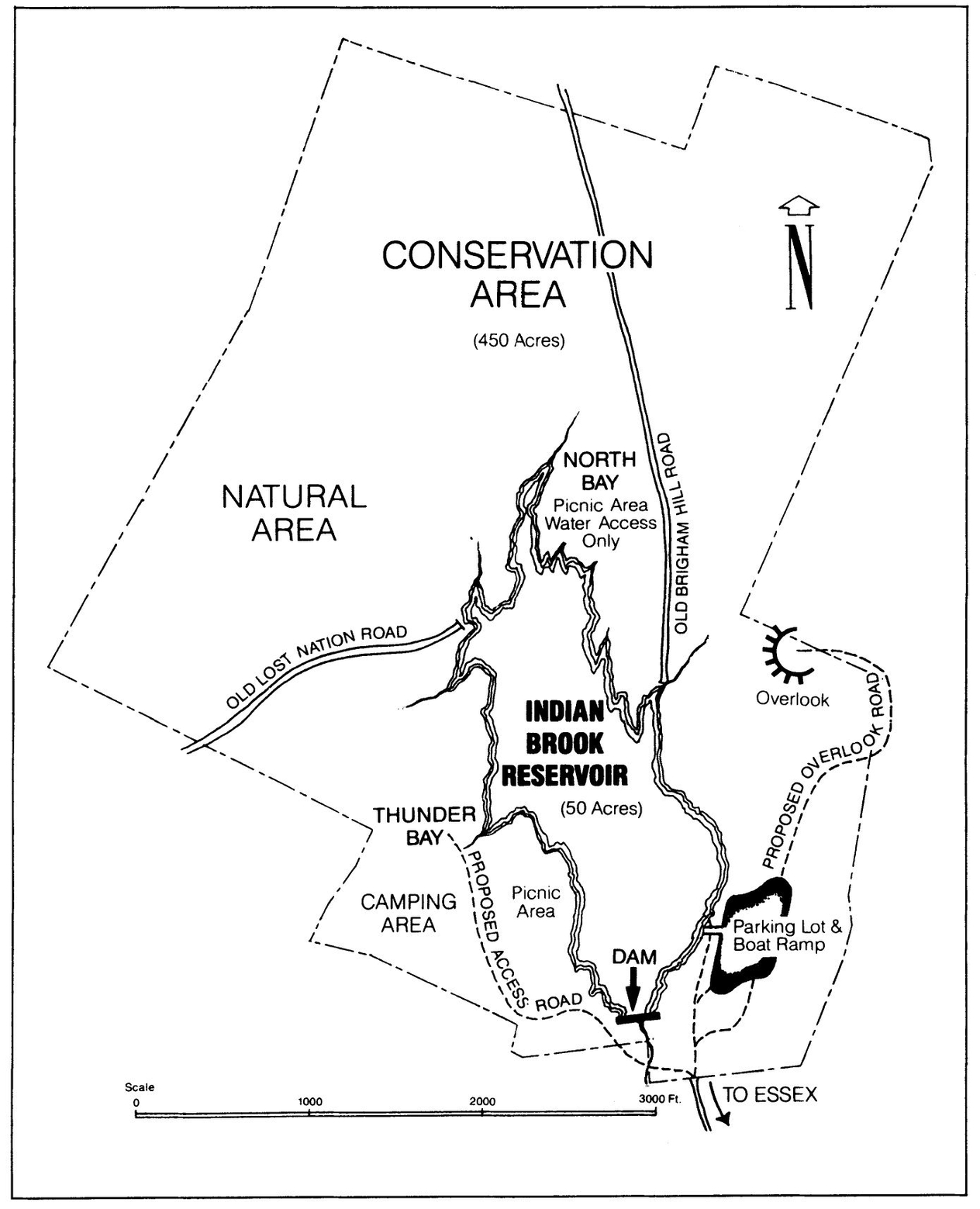

Communitywide activities such as the development of a rural environmental plan usually have a continuing impact on the whole community. One or more proposed projects may capture the imagination of REP participants, projects that continue to shape and influence community actions for a long time. When the quality-environment plan for Essex was completed in 1972, a number of REP committee members led by Ann Harroun turned their attention to a major recommendation of the Essex plan: the acquisition and improvement of the Indian Brook Reservoir.

Indian Brook is a 450-acre hilly and wooded tract containing a 50-acre reservoir behind an old reinforced-concrete dam. The reservoir was located in Essex town but was owned and used for water by Essex Junction. While the REP plan was being developed, Essex Junction was in the process of joining the Champlain water district; in the future the village would get its water from Lake Champlain, not the reservoir. Seizing on this opportunity, the REP committee and the technical team identified the Indian Brook area as having the highest potential for public recreation. It could be used, the plan stated, for “boating, fishing, picnicking, camping, nature trails and scenic overlooks.” Abandoned roads could provide access.

The citizen committee tried but failed to get the town to obtain a direct grant from the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation (BOR) for 50 percent of the cost. Next they turned to the Winooski Valley Park District (WVPD) for assistance (see chapter 9) and just missed a deadline for joint purchase using BOR and WVPD funds. Then the Essex Village Board of Trustees changed their objective from preservation to development and sold the parcel to a consortium of developers—the only party to submit a bid. The bid price was adjusted downward to compensate for a flaw in the title.

Deterred but not defeated, the supporters launched phase two of their campaign, the creation of a support group, the Friends of Indian Brook Reservoir (FIBR). This group enlisted community support for public purchase of the Indian Brook property. The expanded support group pursued the following tactics:

- Creation of a card file of supporters/members. With the permission of the new owners, a sign was posted on the property: “Technically, you are trespassing. If you would like to help protect this property from private development and turn it into a public park, please call FIBR, at [telephone number].” With these signs, and by talking to recreational users at the site, workers gathered names for the card file. Three membership categories were drawn up: active members, persons available for occasional special projects such as fund raisers, and those who would cast favorable votes when the time came. Many teens joined FIBR. They worked hard in all of the activities, brought their parents into the fold, and exerted peer pressure to keep the place clean and reduce vandalism.

FIGURE 1.2. Plan for Indian Brook Reservoir: Major Component of Essex Environmental Plan

- Policing the area to make a good impression. Volunteers regularly cleaned the area of trash and broken glass. Trash barrels painted with the FIBR logo were set out. Returnable cans and bottles were collected and cashed in to buy trashbags. Volunteers with pickup trucks hauled trash to the dump.

- Publicity. Open houses, tours, and canoe rides were held with the public and press invited. Slide shows were presented to private groups and at the polls. Coffee and baked goods were sold at the slide shows. A newsletter was mailed to members. A history of Indian Brook and proposed development plans were circulated and published.

- Surveys. Volunteers conducted surveys at the site to demonstrate the extent of its use and discover preferences for limited development.

- Planning for the area. Harroun, by then on the select board, persuaded the town manager to prepare a development plan reflecting user preferences and an estimate of the costs of that plan.

- Petitions. Two petitions were circulated door to door in the town and the village, one in favor of acquisition and one opposed, in order to demonstrate public opinion to the select board. Accompanying the petitions were color photographs of the site, its history, results of the user survey, plans and costs of development, and its effect on the tax rate. The petitions showed support for acquisition exceeding 90 percent.

This campaign won a lot of members for FIBR (over two hundred), but it did not buy the land. Political pressure had to be applied. Over a period of time, members and supporters of the Indian Brook project gained positions on public commissions and boards. One member, Noah Thompson, University of Vermont extension development specialist, became the chairperson of the Essex Town planning commission. Ann Harroun was also elected to the planning commission, as well as to the select board and later to the state legislature. During the tenure of these two, Essex town adopted and enforced strict subdivision regulations requiring developers to provide water, sewer, paved roads, dual access, and storm drainage in all subdivisions. This made private development of the Indian Brook parcel more expensive and difficult.

In 1987, with private development unlikely, the select board authorized a bond vote for the acquisition and development of Indian Brook Reservoir. The proposal passed overwhelmingly. Unfortunately, there was one more hitch. The positive vote sent the asking price up. The town board rejected the increased price; the members of FIBR held their breath and supported the board. This standoff was resolved when Congress passed the 1987 tax reform act, which eliminated the benefits of capital gains. On December 31, 1987, the eve of the new law’s effective date, the town and the would-be developers signed an agreement for sale.

Indian Brook Park, as it is now called, has a repaired dam, improved access roads, better parking, a new launch ramp for nonmotorized boats, and picnic tables. The park is extensively used by citizens for swimming, canoeing, fishing, hiking, picnicking, skating, bird watching, and cross-country skiing.

While FIBR focused on one project, the rest of the quality-environment plan had not been forgotten. By 1989, twenty-six of the plan’s seventy-six specific recommendations had been implemented. Major accomplishments included floodplain zoning and a subsurface sewage-disposal ordinance, easements for nonmotorized public access over roads in Saxon Forest, increased use of town school buildings and grounds, pedestrian trails in town subdivisions, bicycle lanes along Maple Street, a nature trail at the town’s middle school, a scenic overlook in Winooski Valley, a pool, and four public parks.4

In 1991 another benefit flowed from the 1972 plan. Essex town and village won a Vermont Agency of Transportation grant of $288,090 for construction of a “transportation path.” This award, which came from Federal Highway Administration funds, was made to three towns selected from twenty-four applicants. The 2.8-mile bike/pedestrian path will connect important points of traffic origin and destination within the town and village. Dawn Francis, former planner and now community development director of Essex town, states that the 1972 rural environmental plan with a chapter devoted to trail systems was a major reason for winning the award.

CONCLUSION

In each of these and other examples of REP, planners followed four basic guidelines:

- Public goals were discovered by survey and public discussion.

- Resource inventories were prepared through the cooperative efforts of local citizens, technical experts, and the rural environmental planner.

- Each plan was designed to be environmentally sound, politically acceptable, and financially feasible.

- Objectives included the protection of the natural environment, diversification of economic opportunities, and preservation of cultural values.

Completion to date of over thirty rural environmental plans has led to a pattern of results that permit general conclusions about REP as a creative planning process. The costs of planning in rural areas can be reduced by using the expertise of public, private, and volunteer professionals together with specialists from state universities and, increasingly, graduates of rural-planning programs. This expertise is combined with the extensive knowledge of local citizens to produce a unique plan for a rural community or area. REP uses planning concepts that are relevant to contemporary rural society. REP serves client groups not addressed by conventional urban planning; it protects community values and promotes public access to a quality environment; and it develops a plan in accord with public goals. Because a rural environmental plan evolves through the direct participation of local citizens, it is more likely to be adopted and implemented.

REP can serve as a model for state universities and state planning offices to guide rural communities in local planning. It is a tool for unlocking thousands of dollars’ worth of planning expertise in state and federal agencies, state colleges, and the private sector and for applying this knowledge and skill to local planning problems. The initiative to undertake REP, however, must come from the community. Sources for such an initiative can be diverse: local civic leaders, citizens ad hoc committees, community development corporations, individuals with leadership and organizational skills, and local agencies established to work in one or more sectors of community development.