2

Rural Environmental Planning in Perspective

HUMAN SETTLEMENT WITHIN the present boundaries of the United States did not begin with small towns on the eastern seaboard. Centuries before the establishment of Williamsburg and Jamestown, Virginia, the Hohokam, the Anasazi, and other Pueblo Indian cultures of the arid Southwest designed and built agricultural communities sustained by water-control systems and small farms. Canals, ditches, headgates, diversion dams, contour terraces, and contiguous-grid bordered gardens supported permanent settlements and a sedentary way of life.1 Archaeological remains indicate that these prehistoric peoples used design technology for long-term occupation: thermally efficient pithouses and kivas constructed from twigs and mud, pits and cisterns for storage, as well as outdoor hearths and roasting ovens.2

EARLY SETTLEMENT PATTERNS

Village size and town layouts varied considerably during the early periods of settlement. In many cases planning was haphazard, resulting in informal arrangements of houses and other structures. However, some societies developed complex village, town, and regional systems of planned settlement, most notably the Anasazi of Chaco Canyon:

In the tenth century a distinctive organization developed within Chaco Canyon. Although probably localized at first, the system eventually incorporated an area of about 53,107 km2 of the San Juan Basin and adjacent uplands [parts of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and Colorado]. The Chaco Phenomenon is characterized by construction of large planned towns, the presence of contemporaneous unplanned villages, roads, water-control features, ... and construction of the Chacoan outliers.3

During its period of peak population, around A.D. 1100, the Chaco region included some two to four hundred villages connected by an intricate road network of more than 400 miles to outlying sites. Village designs incorporated major apartment units and ground plans for D-, E- and L-shaped pueblos, curved walls, multifloor apartments of masonry construction (sandstone and decorative veneer walls), open plazas, kivas, and other structures sited and designed for passive solar heating.4 Portions of these village structures still stand and are open for public viewing at the Chaco Culture National Historical Park in Northwestern New Mexico, near Crownpoint.

Some five centuries after the decline of Chacoan culture, Spanish explorers and land-grant petitioners established villages and towns on the northern frontiers of New Spain, diversifying the region’s already-established forms of settlement. Guided by city-planning ordinances embodied in the Laws of the Indies, the Spanish introduced a gridiron system of square blocks and paid careful attention to the layout of plaza, church, streets, and merchant portals; plans provided for the location of house plots and common land for livestock.

The Laws of the Indies, issued by King Philip II in 1573, contained 148 separate ordinances. Prior to settlement, sites had to be selected in proximity to water for domestic and agricultural use. They “should be in fertile areas with an abundance of fruits and fields, of good land to plant and harvest, of grasslands to grow livestock, of mountains and forests for wood and building materials for homes and edifices, and of good and plentiful water supply for drinking and irrigation.”5 Application of the Laws of the Indies varied from one location to another, depending on topography, natural resources, climate, the requirements for social and political organization, and many other factors. Ordinances requiring square or rectangular plazas and governing land use and town layout, however, left a permanent imprint on the landscape of the West and Southwest, as exemplified in early Spanish cities as diverse as Santa Fe, St. Louis, and Los Angeles.6 The criterion of proximity to water is best observed in the hundreds of villages and towns scattered throughout the valley of the Rio Grande and its tributaries in New Mexico and southern Colorado. Some thousand acequias (irrigation ditches) continue to nurture and support village agriculture on a small scale, particularly in the sierras of north-central New Mexico.

EVOLVING RURAL PATTERNS

The rural landscape in other parts of the United States, meanwhile, took shape according to influences contributed by other cultures. The colonists who settled Williamsburg, Jamestown, and Washington, D.C., also built carefully planned towns. In each case the site was surveyed and marked, and all building conformed to a master plan. The eventual opening up of the continent to pioneers, though, did not see widespread application of this orderly procedure. Land-hungry frontiersmen rushed to claim, clear, and settle land without attending to the formalities of surveying or planning.

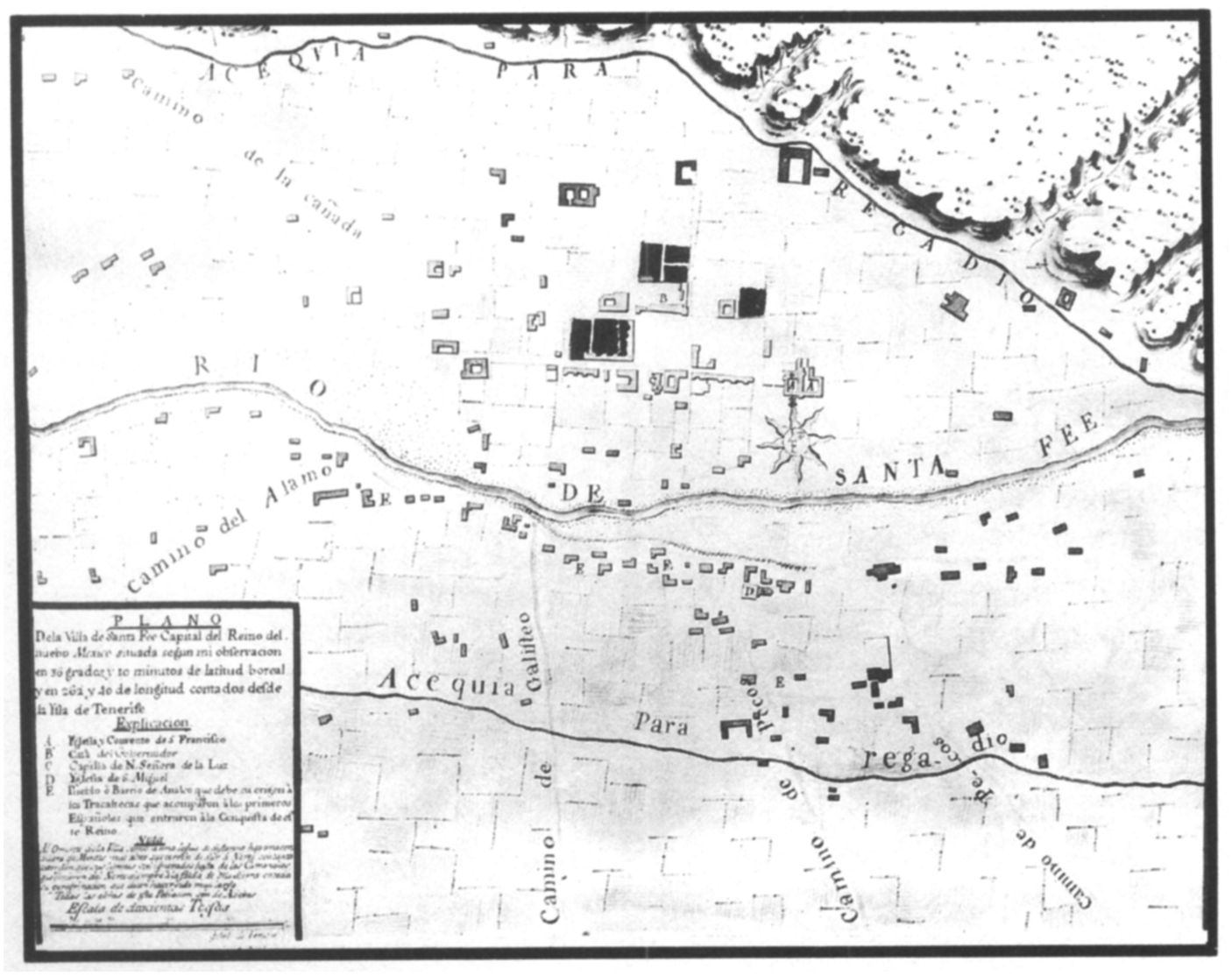

FIGURE 2.1. Villa de Santa Fe. Drawn c. 1766—68, when Santa Fe was still a village, this map by José de Urrutia depicts the Rio de Santa Fe with two acequias constructed by Hispanic settlers to irrigate crop fields and common land as required by the Laws of the Indies. Hundreds of towns and villages in the region continue to reflect colonial ordinance requirements pertaining to town layout and land use. (Courtesy of the Museum of New Mexico.)

The New England states were generally settled according to the frontier pattern. Land in Vermont was granted on paper by New York and New Hampshire governors and settled by woodsmen, squatters, grantees, speculators, and in some cases, draft avoiders. Adventurers of all types cleared and fought for homesteads and speculative acreage. The governments they established were minimal, local, informal, and primarily concerned with maintaining independence from New York and New Hampshire. Individual landowners or small corporations determined land use. Public planning was limited to laying out military highways. This system of a weak state government, strong local authority, and negligible town planning persisted until the 1930s, when the Great Depression together with natural catastrophes forced the national government into concerted action.

From the mid-1930s until well after World War II, federal agencies planned rivers and watersheds for navigation, hydroelectric power, flood protection, and commercialized agriculture. They also constructed dams and planned scenic parkways, national forests, and parks. The states, at this time politically and financially weak, were content to let the federal government take financial responsibility and, with it, responsibility for planning and decision-making.

CONCEPTUAL BASIS OF REP

While the tactics and procedures of REP developed more recently, its basic values and theoretical concepts can be traced back to the utopian experiments of Robert Owen and others, as set out in Ebenezar Howard’s Garden Cities, as well as to large-scale projects in regional water-resource planning such as the Tennessee Valley Authority. As regionalism took shape in America, planners grew more interested in environmental quality, public involvement, and equity.

In the early 1920s, concern over uncontrolled growth in industrial centers as well as aggressive mining and logging in rural regions caused a group of urban planners to form the Regional Planning Association of America (RPAA). The city, they believed, “could only survive in organic balance with the totality of its regional environment.”7 That is, it could survive as a cultural and civic repository for civilization’s achievements only if it existed in harmony with its rural surroundings. The RPAA saw regions not only as geographic areas but also as entities that combined geographic, economic, and cultural elements in distinctive configurations. The challenge was to create balance within a region and between rural regions and metropolitan centers.8

This concept established the foundation for a view of regional planning articulated by Benton MacKaye, a forester and one of the founders of the RPAA:

Cultural man needs land and developed natural resources as the tangible source of bodily existence; he needs the flow of commodities to make that source effective; but first of all he needs a harmonious and related environment as the source of his true living. These three needs of cultured man make three corresponding problems: (a) the conservation of natural resources, (b) the control of commodity-flow, (3) the development of environment. The visualization of the potential workings of these three processes constitutes the new exploration—and regional planning.9

Another prime mover in the RPAA, Lewis Mumford, combined the concept of regional planning with the idea of communal education. Mumford also redefined the planning process, normally undertaken solely by professionals, to include community participation. “Regional plans are instruments of communal education; and without that education they can look forward to only partial achievement.” 10

These two ingredients of regionalism, ecological balance and community education, were taken up by Southern regionalists concerned about the problems of endemic poverty, underdevelopment, cultural disintegration, and the ravaging of Southern natural resources by Northern investors. Regionalism became for them a symbol of self-determination.

One of the most important advocates of regionalism was Howard Odum, a Southern sociologist with populist inclinations. In Odum’s words, “regionalism ... represents the philosophy and technique of self help, self development and initiative in which each areal unit is not only aided, but... committed to the full development of its own resources and capacities.”11 Regionalist thinking as expressed by Odum and others had evolved from the search for an urban-rural environmental balance to the search for an economic and cultural balance within and between regions.

The heart of the problem [of balance] is found in search for equal opportunity for all the people through the conservation, development, and use of their resources in the places where they live, adequately adjusted to the interregional culture and economy of the other regions of the Nation. The goal is, therefore, clearly one of balanced culture as well as economy, in which equality of opportunity in education, in public health and welfare, in the range of occupational outlook, and in the elimination of handicapping differentials between and among different groups of people and levels of culture may be achieved.12

Regional planning as envisioned by the early planners of the RPAA—that is, planning as a holistic discipline that would create balanced regions, conserve cultures, equitably distribute wealth and opportunity, and develop environmentally sound growth models—was never implemented. Rather, it was eclipsed by the military and economic mobilization of World War II and the ensuing postwar economic explosion, which occurred as wartime industries retooled to meet pent-up consumer demand. According to John Friedmann and Clyde Weaver, “Growth would become a substitute for distribution. . . . With economic growth, the labour force would be fully employed. . . . In a growth economy, everyone was bound to share in the general prosperity. . . . Re-distribution could then be either avoided altogether or more easily resolved than under the conditions of stagnation.”13

RECENT RURAL PLANNING

The contemporary period in rural planning was ushered in and stimulated by the expansion of environmental consciousness in the mid-1960s. From that time to the early 1980s, in a climate of increasing public concern over rural poverty, state and regional planning intensified along with rural community planning. Encouraged by federal policy, citizen participation expanded to support and guide local governments and community-based organizations as they took on the new role of planning. Threatened by multiple environmental crises, states adopted new planning goals and various means of achieving them. It was during this period that a number of state universities—the University of Vermont, Appalachian State University in Boone, North Carolina, and the University of New Mexico, among others—began to address the needs of small communities in their planning programs.14

A succession of federal programs between 1965 and the early 1970s stimulated and supported community development planning at the state and local levels. In 1972 Congress passed the Rural Development Act, which designated the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) to oversee federal involvement in rural development. For the first time, an assistant secretary position was created to coordinate various USDA-sponsored agencies such as the Farmers Home Administration (FmHA), the Rural Electrification Administration (REA), and the Rural Development Service (RDS).

The Rural Development Act also provided grants to finance the process of planning for area development. These “section 111 planning grants” were intended to encourage and underwrite comprehensive planning for rural communities. Grants were obtained by states, substate districts, local governments, and community-based organizations to design housing, economic-development, water and sewer, and energy projects. More than any other single source, however, the categorical programs, which originated in President Johnson’s War on Poverty during the mid-1960s, fueled and financed thousands of rural projects in health, education, job training, economic opportunity, social services, housing, community centers and other local infrastructure.

After more than a decade of substantial federal intervention, the Carter administration capitalized on the growing perception of the need to coordinate federal rural policy with local and state implementation. Between 1976 and 1980, the federal executive departments undertook collaborative projects through a series of interagency joint agreements. Various departments (labor; health, education and welfare; agriculture; housing and urban development; energy; and transportation), the Economic Development Administration, EPA, ACTION/VISTA, and the Community Services Administration pooled grant dollars in order to finance local initiatives in such areas as rural housing, health, water and sewer, education, social services, job training and employment, economic development, energy, transportation, communication, and natural resources. The aim of the Carter policy was to stimulate comprehensive planning on the state level by setting an example at the top executive levels of government.

In September 1980, the rural planning legislation of 1972 was amended by passage of the Rural Development Policy Act. This act reiterated the role of the USDA in providing leadership throughout the executive branch. It also mandated that federally sponsored rural development programs coordinate efforts with state and local governments. Annual authorizations for FmHA section 111 planning grants were increased from $10 to $15 million.

In 1981 the Reagan administration took office. By then, the Rural Development Policy Act required the submission of updated reports on a “national strategy” for rural development. Successive reports from the Reagan administration, however, deemphasized the leadership role of the federal government and instead called for a deregulated and decentralized approach to rural development. Greater involvement by and partnerships among state and local governments, the private sector, volunteers, and the farming community were strongly advocated by the Reagan administration.15 Many of the categorical programs that had earlier financed interagency agreements were eliminated, cut back, or consolidated into block grants to the fifty states. The executive branch chose to pursue a macro-policy of economic growth that it contended would trickle down to all of America, including the rural sector.

During both the Carter and the Reagan administrations, there was mounting evidence, however, that neither federal intervention nor trickle-down economic development strategies were benefiting chronically poor rural areas. The gap between less developed rural regions in the South, Southwest, and West and more developed regions was growing. Using per capita income, unemployment rates, and other economic indices, the USDA tracked counties where poverty persisted. Between 1949 and 1979, nearly one-fifth of the rural counties in the United States remained “persistent low income counties,” and one-quarter of rural counties or parts of rural counties fluctuated between persistent poverty and less-persistent poverty during this period.

Industrial recruitment strategies underwent a reevaluation in the 1980s. In 1985 the USDA’s Economic Research Service released a series of studies done in clusters of counties in Georgia and Kentucky where manufacturing plants had located and in the Ozarks where resort tourism combined with manufacturing to create new economic growth. The aim of these studies was to determine who had benefited from the economic growth between 1974 and 1979. The following quote from the Kentucky study typifies their findings:

Overall employment growth in rural areas will probably not benefit all households or residents in that area. In a nine-county area of south-central Kentucky, rapid employment growth between 1974 and 1979 did create new job opportunities. However, only 18 percent of the households had members who took advantage of new jobs. The employment growth also did not reduce the area’s overall poverty level.16

The Reagan administration did not address conditions of persistent poverty; instead it responded to the farm crisis by supporting legislation that would diversify rural economies by making available loan capital to finance development in nonagricultural sectors such as tourism and small business. In addition, the Reagan White House endorsed new legislation at the federal level to establish “enterprise zones” which, combined with state and local commitments, would provide tax, financial, regulatory relief and various incentives to businesses willing to locate in distressed rural and urban areas.

In 1988, after numerous false starts, Congress passed “Title VII: Enterprise Zone Development” as part of the Housing and Community Development Act of 1987. This legislation called for the federal designation of one hundred enterprise zones, at least one-third of which had to be rural areas. Indian reservations were also mentioned as eligible sites. Meanwhile, by 1989, thirty-seven states had enacted their own enterprise-zone legislation.17 Subsequently, designated projects were reported in over two thousand local jurisdictions, urban and rural. The decade of the 1980s closed with continued emphasis on local solutions to the problems of persistent rural poverty. This shift in policy brought greater sensitivity to the diversity and complexity of rural America and the major postindustrial forces shaping emerging and future needs.18

NEW DIMENSIONS FOR RURAL PLANNING

Rural Environmental Planning asks people to define their own goals. All rural settings are different, of course, and the conditions of each produce unique insights. Many rural communities do, however, share the same general goals. For example, enhancing the quality of life, improving economic opportunity, and protecting the natural environment are aspirations of the majority of people in REP communities.

SELF-RELIANCE

Throughout the 1980s the authors of this study noted new dimensions emerging in the formulation of community goals, in particular, an emphasis on increased self-reliance, reduced economic dependency, and a diversified economic base. Regarding the first, self-reliance, it should be noted that the term is used here with some caution. Self-reliance has become part of the development lexicon, in particular with reference to less-industrialized or nonaligned countries. It has almost as many meanings as authors who write about it. It has been utilized in conjunction with both autonomous utopian communities and practical strategies for feeding people.

Much of the current interest in self-reliance results from dissatisfaction with past development strategies formulated by agencies and institutions in the industrialized world and applied to the so-called third world. Strategies emphasizing rapid industrialization, capital-intensive tourism, or the commercialization of agriculture often created single-product economies lacking adequate infrastructures. As these economies grew more and more dependent on, say, single-crop harvesting or single-product mining, or manufacturing, planners and economists noticed that the economic gap between rich and poor was actually widening. The resulting system could not generate its own investment base to create a diverse and balanced economy because the profit was exported and did not enrich the local economy.19

Similarly, until very recently, rural communities in the United States were encouraged to join the mainstream economy by courting industry, luring capital-intensive tourism development, and industrializing the agricultural sector, and welcoming extraction industries—all with little sense of what it would mean to lose local control over community resources. This approach resulted in rural economies skewed to support a single product or subject to a boom and bust cycle that left them open to chronic depression and dependency.

Self-reliance does not mean that a community is isolated from the mainstream economy. Self-reliance is used here to mean the regeneration of the community through community-controlled development of its own resources (natural, human, and cultural). This includes the determination of the manner in which resources relate to both the community’s internal economy and the mainstream economy. Regeneration involves the separation of unhealthy social and economic dependencies by diversifying the sources of local income, increasing the net flow of money into the local economy, developing a self-investment capability, and improving local productivity.

Planning for self-reliance requires broad citizen participation; the process determines the product. Self-reliance and top-down planning are mutually exclusive concepts. Self-reliance cannot be achieved in a planning process that depends entirely on professionals, agencies, or political leadership outside of the community. For a community to achieve and maintain self-reliance, it must itself develop the fundamental tools of planning. In REP these tools are communication, inventorying, goal development, evaluation, and decision-making.

EXURBIA: THE CHANGE AND THE CHALLENGE

An increasingly important issue that many rural jurisdictions and small towns will have to deal with in the 1990s and into the twenty-first century is a new kind of low-density growth that is not suburban in character and not even directly connected to an urban area. This phenomenon, called “countrified cities” by Joseph Doherty20 and “the new heartland” by John Herbers, is a new form of exurbia. Herbers observes that

the new-growth areas are different from any kind of settlements we have known in the past . . . [and] of such low density that they make the old “suburban sprawl” seem dense. Subdivisions, single-family housing on five- to 10-acre lots, shopping centers, retail strips, schools, and churches, all separated by farms, forests, or other open spaces, are characteristic.21

They are seldom found on flat, rich farmland, which continues to lose population in all regions. Nor are they part of the back-to-the-land movement of the 1970s that drew those disenchanted with American civilization to rural communes. Rather, the new communities are made up of a prosperous, adventurous middle class superimposed over small towns and countryside in a way the suburbs never were.22

According to Herbers, the U.S. Census Bureau data for the period from 1980 to 1985 shows the greatest growth to be in the farther reaches of the exurban areas—sixty to seventy miles in all directions from New York, two and three counties removed from such cities as Atlanta, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Chicago—and in small metropolitan areas that are in themselves low density, anticity developments, such as Ocala, Florida, Edinberg-McAllen, Texas, and Chico, California. Herbers perceives that much of this growth

is a product of what some authorities call a post-industrial society. With the decline of heavy industry and the rise of a service economy, neither factories nor office buildings need to be clustered near sources of raw materials and water or rail transportation. For the first time in American history, both businesses and workers can settle pretty much where they please. And where they please is not the large city.23

This development is relevant to REP in the sense that rural and small-town beauty can be considered a potential economic resource. Development based on the appeal of a rustic, historic, or scenic place, if balanced with the community-defined concerns of health and well-being, can enhance economic diversity and hence sustainability in that place. Simply put, many small communities and remote rural areas are attractive to new residents and businesses precisely because they are small or remote. The risk, however, is that disconnected exurban development will overwhelm or destroy the rural quality that was the initial attraction.

Often the infusion of new settlers and enterprises in unspoiled rural environments is only indirectly connected to the traditional economic model of an urban-regional hinterland. Increasingly, economic activity can be geared toward a nationwide or even international market. Examples are the dulcimer crafts of Appalachia, the pottery of New Mexico, and the weaving of the Navajo Nation.

In a paper presented to the American Collegiate Schools of Planning Conference, Edward T. Ward, professor of planning at California Polytechnic State University, expanded on the premise that a new nonmetropolitan reality is emerging.24 Ward ascribed the reverse migration from urban to exurban places to the deeply rooted American tradition of small town and country living and Americans’ ambivalent feelings about cities. Multiple surveys have consistently shown that “a majority of Americans would prefer to live in small cities, small towns and the countryside. The big change now is that more people are able and willing to act on their preferences, even to the extent of trading off higher incomes.” The opportunity and challenge for the twenty-first century, according to Ward, is for “communities that foster diversity, not large concentrations of sameness; that have a continuity with the past as opposed to trashing it; that go beyond the suburbs in blending development with nature; and which provide choices, quality, and an aesthetic . . . that is meaningful to people.”25 Not achieving this diversity, continuity, and blending with nature risks the deterioration of the character and amenities that attracted people to the rural environment in the first place. Clearly, the quality of rural places is a finite resource.

Herber’s and Ward’s analyses suggest that in the preparation of a rural environmental plan it is important to identify valued aspects of rural areas and small towns and to make explicit how those aspects differ from traditional features of urban and suburban areas. Criteria for exurban development include maintaining differentiated population density, mixing income levels and age groups, providing services to both clustered and dispersed populations, protecting natural systems, enhancing agricultural and other biologic productivity, promoting a sustainable and self-regenerating economy, and managing an aesthetic environment where land, water, and vegetation, not buildings, are the dominant components.

CONCLUSION

Rural planning in America has a long and rich history that includes indigenous cultures as well as cultures introduced from Europe and elsewhere. For much of American history, though, rural planning was limited to new settlements, to the outskirts and suburbs of cities, and to large economic regions or natural-resource areas. Between the 1960s and the early 1980s, rural planning evolved from regional planning as a result of federal subsidies for small towns and rural jurisdictions. Rural planning as a discipline in North American universities and colleges is an even more recent development. A decade ago very few planning schools included rural planning in their curricula; the number is now increasing. It is becoming more generally recognized that rural communities are not just “unformed” or incipient cities but rather socially and culturally interdependent groups of people with lifestyles, public goals, political structures, and social values different from, sometimes sharply at variance with, those of urban dwellers. Diversity results in a need for rural planning strategies that will help people to pursue their public goals and to eschew the unwanted or unintended influence of urbanization.