3

Rural Environmental Planning: Organization and Process

LET US ASSUME that from your experience in your own community, from what you have read in this book, and from your knowledge of rural problems and opportunities, you would like to know how to get a rural environmental planning process started. What can you do? At first the task may appear to be so complex that you do not know where to begin. Although the issues to be addressed are complex, REP can be broken down into a series of steps that the citizens and leadership of any rural community can take, one after another, and achieve significant community goals. The entire planning process can be divided into three parts: start-up, create the plan, and implementation. The steps necessary for each of these parts are presented in this chapter.

START-UP

How does the process get started? In the experience of the authors, start-up activities fall into three common phases: initiation, discussion, and organization. While the hard work of data collection, goal development, and plan evolution comes later, start-up is so critical to future success that it requires special comment.

Initiation. In the beginning someone gets an idea that some aspect of the community could be improved through collective action. This initial spark may come from seeing or hearing what other communities have done. It may be a reaction to the chronic problem of high unemployment or exodus of young people. It may be touched off by rumors of a large development that is perceived as a threat to the rural way of life. Or it may result from the discovery of new opportunities for local development. This vision of a better community is all important, but it must be connected to an understanding of the political process, otherwise it will die. To translate the vision into a feasible plan of action that will appeal to a large portion of the community, a further step is needed—discussion.

Discussion. All ideas for community improvement, even the best ones, need a lot of informal discussion before they can be successfully implemented. A substantial amount of give and take is necessary to test whether a new concept is worth the work required to bring it about. The more a concept is discussed, the more people there are who will feel a part of its development and who will be personally motivated to support it. A major advantage of informal community discussion is refining and improving a proposal. Objections can be met; details can be worked out; examples can be studied; possible opponents can be persuaded. Discussion in small groups and communitywide gatherings will show how the proposal fits into the overall scheme of things: how it relates to regional planning, how planners can take advantage of special opportunities for financial assistance, and how the special talents of local people can be drawn upon. A discussion period may also produce community participants and potential activists who will be indispensable in the next phase—organization.

Organization. After discussion has informed the community of the possibilities of REP and interested individuals have stepped forward, it is time to proceed in a more structured way. Often by this time leaders have emerged who have the respect and support of the active citizen group. An ad hoc committee may elect a spokesperson to conduct meetings and a secretary to keep records, or an elected board may appoint members as a citizens committee.

At the first meeting a number of public goals may be discussed. Committee members may consider sources of professional assistance, discuss how to fit REP into the cogs of local government, and indicate their concerns and possible subcommittees on which they would like to serve. The makeup of the new organization will directly reflect the objectives of the members. If one goal is to plan for sustainable economic development, an effort should be made to include representatives of all groups with a direct interest in the economic structure of the community. If another goal is to develop a plan for environmental protection, the group should include those with a special interest in or knowledge about environmental issues. If interest is expressed in a trail system, members should include hikers, cross-country skiers, and bicyclists. If the priority is tackling poverty and unemployment, as reported in some recent REP cases, then members should include the appropriate representatives.

PROCESS AND ROLES

The creation of a rural environmental plan is a participatory process supported by expertise from public agencies, universities, nonprofit organizations, private individuals, and local citizens. A draft plan is reported and discussed in subcommittee sessions and in meetings involving as many of those affected by the plan as possible. The final plan, after adoption by town, village, county, tribal government, or other jurisdiction, then serves as a guide for long-term community development by public, private, and community-based organizations.

The process of creating a rural environmental plan requires a working relationship among three participants or groups: the client, the planner, and the technical team. The client initiates the plan. The client may be represented at various times by an elected board, an appointed or ad hoc advisory commission, a nonprofit organization, those who speak up at public meetings, or those who respond to a community survey. The ultimate clients of a rural environmental plan, though, are all those who are or will be affected by the plan.

At the end of the start-up phase the client group may organize in a number of different ways. It may become a conservation commission appointed by elected officials to assist with the development and implementation of the plan. This has been done in Massachusetts and other Northeastern states. Or the planning commission itself may undertake such planning. An ad hoc committee of citizens could provide the engine for developing an environmental plan. There are other possibilities, but whatever form this group takes, it will need to have committed leadership, good connections with local government and community organizations, and volunteers to help develop the plan.

After the REP committee is organized and there is general agreement on the direction of planning, subcommittees are set up. These should be few in number and organized according to inventories to be made and chapters to be written in the plan. To clarify the role of subcommittees, let us outline several of their typical assignments.

Public Goals Subcommittee. Review chapter 4 of this book; draft goals questionnaire; obtain suggestions from full committee; get help from rural environmental planner to finalize questionnaire; distribute questionnaire to all households; collect questionnaire; tabulate it; write up results; report results to full committee and to public.

Natural Areas Subcommittee. Review chapter 6 of this book; ask natural scientists and citizens for a list of natural areas; study identified public goals; write report describing natural areas and proposing protective measures.

Agricultural Subcommittee. Review chapter 7 of this book; get information on agricultural activity, trends, and numbers from technical team; study public goals for agriculture; get technical recommendations for plan to achieve those goals; write report as a draft chapter for rural environmental plan.

Economic Subcommittee. Review chapters 12, 13, and 14 of this book; make an economic profile of town; list alternative development strategies; find examples of other communities working on sustainable economic development; get suggestions from state development department; present and discuss findings in public meetings, then summarize as input to plan.

These examples show the general procedures of subcommittees. Members visit and observe their subject area; review literature; get help from the REP planner and technical team; study results of a public goals survey; discuss findings, options, and recommendations; and then summarize the results as a draft chapter for the plan.

The person who provides services should communicate all the steps and concepts of the planning process to citizens and town officials, facilitate the work of the subcommittee, oversee data collection and inventories, assist citizen subcommittees in drafting and editing chapters, and insure the input of citizens and local officials. This person should also provide drafting maps, collect all materials in the form of a plan, incorporate changes, obtain approvals, and publish the plan. These responsibilities can be performed by a person with formal training in planning or someone with skills in community development.

In states with a planning degree program at the state university, graduate students can participate in rural planning as part of their course work, professional projects, or theses. A graduate student or recent graduate can serve as the on-site planner. He or she, along with a professor of planning, may attend the first meeting of the elected board or planning commission; from then on, the student is the planner designated to attend local meetings. The student visits government agencies and other organizations to work on the inventory and receives advice and guidance each week from the university planning faculty in preparation for the next week’s work.

A variation on the university model is for a class of students in an advanced-planning studio to assist in developing the plan. While a semester is a short period, experience shows that a team of ten to fifteen students, working under faculty supervision, can accomplish a lot. However, a semester or two of additional work by a graduate student and the citizen planning committee may be necessary to complete the plan.

Typically, the university planning faculty consists of a core planning group and a support group. The core group often includes an environmental or economic planner, a landscape architect, a geographer, a cartographer, or a civil engineer. The support group may consist of professors in various departments—geology, soils, hydrology, social planning, anthropology, recreation, health services, resource economics, business management, public administration, and law, among others—who help students to collect data and draft recommendations.

A university planner is limited by the number of plans that can be completed in university studios, by the number of graduate planners, and by the funds available to rural jurisdictions. Even if there are dozens of villages, counties, small towns, or Indian pueblos that would like rural plans, a university may be able to serve only a few clients each year. In states without planning programs at the state university, rural communities can advocate the adoption of such, meanwhile contacting a nonprofit organization experienced in community development.

The technical team consists of professional and technical experts who help subcommittees to conduct inventories and draft recommendations. They may be employees of federal, state, or county agencies, or they may be retired persons, private-sector volunteers, or resident professionals. In some cases they may be paid by not-for-profit or philanthropic organizations. Paying for essential technical services is often necessary to assess problems correctly and formulate solutions. Whatever the arrangement, technical personnel should be selected on the basis of talent and experience so that sound decisions will be made.

In early REP projects the technical team consisted of a representative from the USDA’s Soil Conservation Service (SCS), the county forester, a county agricultural extension agent, and a state university faculty member experienced in rural planning. With the Reagan administration’s elimination of USDA section 111 planning grants, as well as grants to the Department of Housing and Urban Development and the Bureau of Recreation, access to many federal agencies was restricted. The administration also reduced personnel and cut technical-assistance programs in agencies such as the SCS and FmHA. Although the Reagan administration advocated the provision of comparable services at the local and state levels, in most states this did not happen.

By the mid- and late 1980s other more innovative strategies were utilized to obtain expertise and funding. These strategies attracted volunteer or resident professionals from the private sector; technical experts from state agencies and universities; private, philanthropic, church, and other not-for-profit funding sources; and community organizations. Examples of specialists who can supplement REP technical teams are state or county foresters, agricultural extension agents, fish and game biologists, housing specialists, and economic development specialists.

PARTICIPATION IN THE REP PROCESS

REP affords community residents many opportunities to participate and make a difference. In summary, citizens can do the following:

- Initiate the REP process

- Contribute ideas from the beginning and gradually refine them

- Suggest questions for the goals survey

- Volunteer for subcommittee work

- Organize and participate in field trips

- Conduct resource inventories with technical team assistance

- Review literature, especially case studies of successful projects elsewhere

- Draft chapters and sections for the plan

- Attend public hearings and other meetings

- Serve on decision-making and implementation bodies such as conservation or planning commissions

Public participation has become an accepted part of the community planning process. Usually, representatives from various parts of the community are invited to meetings, or meetings are advertised and all are invited to attend. In many rural communities meetings may work well. In multicultural communities the results are not always so good. Meetings, to be successful, should be viewed as forums for reporting and advancing work. Participants should leave a meeting with some idea of the steps that need to be taken before the next. The action can be just taking a set of questions back to a constituency group who may not be meeting-goers but who may have information, insights, or other contributions to make to the process.

Residents unable to attend can be encouraged to serve in many other capacities, for example, organizing and leading field trips for the subcommittees. Resource inventories, field trips, and goal surveys inform the community as well as the decision-makers. The gathering and presentation of information are crucial to participation and skills building. They are also the reason the REP process cannot be hurried. It is not enough to outline an issue and ask participants to decide on solutions. The vision of where the community can go and the information on how to get it there requires input from people within the community as well as from the technical team and project examples from other communities. The exchange of information among subcommittees, the technical team, and outside communities is necessary to stimulate involvement and accelerate learning.

Experience in REP cases has shown that one way to increase community involvement and confidence is to address and solve a specific problem early in the planning. An environmental problem such as toxic waste dumping or an overflowing landfill will draw out local leadership that can then be tapped to assist with long-term planning. Residents may want to meet basic needs before moving on to the creation of new businesses or complex kinds of environmental preservation. Some services, such as meal delivery to senior citizens, can be developed into a business that both serves basic needs and provides jobs for some residents. This gradual movement from preliminary planning to more comprehensive planning is not just for less experienced groups. As John Dewey and John Friedmann point out, “Through experience we come not only to understand the world but also to transform it. As in a spiral movement, from practice to plan and again back to practice, it is the way we learn.”1 The process of discovery will engage people in authentic learning where, collectively, they create a vision, determine community goals, and then gain the skills needed to take steps toward realizing their vision.

GETTING UNDER WAY

A successful plan requires a core of active citizens who understand their community and desire to improve it through the instrument of self-government. In communities where elected officials do not recognize the value of planning, concerned citizens may have to initiate projects themselves with the hope that official attitudes will change over time.

Rural towns, districts, or counties become ready to plan at differing rates. Communities, like families, go through cycles of growth, stability, decline, and resurgence. Community leadership also varies in strength and quality over time. A prosperous community may feel no need to plan until a crisis arises. A declining community that has lost its leaders may need help in getting started. Or the existing leadership may lack the vision and imagination to try new ways. It is important for the rural planner and the people in an area to recognize their own unique situation in order to estimate the potential return of time invested in a plan. There is no precise measure of the factors involved, but there are some general REP guidelines that have evolved over the years.

If there is a small group of recognized community leaders who want to consider the REP process, then a start can be made. If the community has an annual fiesta, holiday celebration, library fund-raiser, or other similar event, it probably has enough leadership and cohesion to consider REP. If the community has recently undertaken, primarily through its own effort, some major collective enterprise—such as building a baseball field, a fire station staffed with volunteers, or a community center—it has the necessary leadership for planning. If, at a public meeting called to discuss REP, there is a good turnout and a majority of those speaking are ready to take positive action, then REP will probably bring results.

THE UNIT OF ORGANIZATION

Local government serves as the framework for planning. Without such a political unit—many unincorporated communities in the South and West lack one—a community can have a local organization provide the framework for planning. The town or village government serves for rural town planning, and county or tribal government for rural area planning. However, if the planning area is synonymous with a natural-resource area or region, such as a river basin, a multiple-town lake basin, or a mountain region, then a special organization separate from local political units must be established. This multijurisdictional board can represent, communicate with, and provide feedback to the political units that must implement the plan. For example, to plan the Camels Hump mountain region and the Winooski River valley in Vermont, special state legislation setting up multiple-town administrative units was sought and enacted.

In some natural-resource areas, alternative agencies, nonprofit organizations such as nationwide environmental organizations, community-development organizations, or subunits of the state such as soil and water conservation districts or irrigation associations provide a framework for natural resource planning. In special cases, a coalition of interest groups can serve as the public’s representative in the development of a plan. Such a coalition might include representatives of a farmers’ or ranchers’ co-op, the local wildlife preservation society, or representatives of natural resource and planning disciplines at the state university. The plan is submitted to the elected representatives of constituent communities. In some unincorporated areas, constituents served by the plan may be represented by a nongovernmental organization such as a grange, an irrigation association, or a nonprofit development corporation.

SCHEDULE AND PROCEDURE

How long does it take to develop a rural environmental plan? What is the procedure? The longest and most difficult period is often getting ready to plan. It may take the people in a rural area or small town a long time to move from the perception of concern to identify needs, goals, possible futures, and then to get organized, to identify agencies and resources to assist in the planning process. The time needed for getting started can vary widely, from a few months to a few years. The amount of time actually needed to develop the plan is determined more by the ability of participants to learn and to set goals than by the actual number of hours that go into inventorying and planning. A six- to twelve-month period is usually sufficient in a small community or rural area to conduct the technical tasks of inventorying resources and drafting a plan. Experience shows that interest tends to decline after a year of effort. Following public review and adoption, implementation of the plan may take several years.

The procedure for developing the plan also varies widely from case to case. There is no single prescription to fit all cases. The options and steps outlined below are general suggestions that have emerged from two decades of diverse experience in rural environmental planning.

CREATING THE PLAN

The first step in creating a plan is to hold a special information meeting with the town or village council or with the county or other jurisdictional board. This meeting provides an opportunity for the citizens and community leaders to express their concerns, objectives, and priorities. It also informs community officials about the concepts, purpose, and process of rural environmental planning. Typically, the prospective planner explains the method of developing a plan and the need for participation of all interested parties. The dual goals of economic development and environmental protection are explained, and the need for local approval of recommendations is clearly stated. Citizen input and planning costs are discussed. Also, local officials are invited to visit other communities where rural environmental plans have been completed to learn about REP and observe its results.

A project budget should be discussed at this meeting. Even if planning is done by salaried public servants, it is still necessary to estimate a price tag for additional planning costs. If a rural community gets planning service free, it will tend to attach less worth to the resultant plan. However, if the jurisdiction is charged something for mapping and publishing the plan, then the elected board and citizens have a stake in the outcome. If planning occurs under the auspices of a community-based organization, the budget process should include the preparation of funding proposals.

After a decision is made to proceed, the elected officials or sponsoring organization may send a letter to the rural planner stating the scope of work to be done and requesting assistance for the development of a rural environmental plan. The letter should include a budget and identify the liaison person. The planner then responds to the letter, confirming the agreements and describing how planning will draw on the skills of the technical team.

APPOINTING COMMITTEES

When a rural jurisdiction is involved from the outset, it is a good idea to appoint a REP committee or, in some larger areas, a natural-resource district or other multiple-jurisdiction board to work on the plan. An existing planning commission may serve as the REP committee, or the new committee may be a subcommittee of the planning commission. This arrangement achieves two objectives: it prevents an existing planning commission from feeling that it is being bypassed, and it insures that all subcommittee work will be fed to that commission and therefore into the established planning procedure. An alternative is for the elected board to establish a separate conservation commission or to designate a community-development organization to work on the plan. If this procedure is followed, then the proposed plan is submitted as a recommendation to the planning commission, which in turn considers and processes it just as they would any plan presented to them by other planning consultants.

The composition of the REP committee is determined by several factors, among them the scope of the planning task and which individuals have volunteered their services. Special effort should be made to inform and involve all interested groups. This will reduce unforeseen friction and help to balance conservation and development goals.

Much of the fieldwork, creative thinking, and concrete proposals that produces a community plan takes place in subcommittees. As we have seen, they are organized by matching inventory subjects with the interests of volunteers. Subcommittees vary according to local situations and interests; typical subcommittees include those on agriculture, recreation, water resources, economy, natural areas and wildlife, and history and rural character. Individuals may join more than one subcommittee, or a subcommittee might complete its work and the members join another subcommittee that needs more hands. In general, half a dozen subcommittees should be enough for a full environmental plan. Related subjects may be combined in subcommittee to keep the number at a manageable level. With the assistance of the planner and the technical team, each subcommittee gathers data, collects recommendations, considers goals, and then drafts a chapter for the plan.

DISCOVERING PUBLIC GOALS

One of the first tasks in creating a plan is to conduct a goals survey of as many members of the rural community as possible. The purposes of this survey are to get opinions on issues and on the potential goals identified in the start-up period or at the first information meeting; to discover additional issues, unrealized opportunities, or goals; to establish priorities; and to attract interested people for work on subcommittees.

Experience in the REP process has demonstrated the importance of a 100 percent attitude survey as one of the foundations of a democratic planning process. In small rural communities a one-page survey can be mailed or hand-delivered to every household. Even in larger rural areas the cost of mailing a single-page questionnaire to all households can be more than offset by the benefit of quick, inexpensive input into the planning process. A majority response indicates prevailing views; a minority response identifies goals for further study. There are additional benefits to questionnaires: information can be transmitted through them, and citizens often feel that their views are valued as a result of being asked for an opinion. Public goals are not permanently determined by a goals survey, but may continue to evolve as the planning process proceeds.

INVENTORYING RESOURCES

Inventorying the assets of a community—natural, cultural, and human—is a major task in planning and can take a significant amount of time. Inventorying is done by citizens on subcommittees working with the rural environmental planner and with the technical team. The objective is not to produce a detailed research report on each subject but rather to collect information, both from published sources and from direct observation, to get the whole picture of a community, including its history, character, and potential. Inventories are not just background information; with help from the best experts on each subject, they provide an opportunity to collect proposals. Combining inventories with the advice and guidance of experts results in a list of general and specific recommendations to take to the public for consideration in the next step, public review. The importance of the inventory step is marked by the fact that eight chapters in Part II of this book address this aspect of rural environmental planning.

DRAFTING AND DISSEMINATING THE PLAN

After inventorying, collecting recommendations, and holding public hearings, it is time to assemble, publish, and distribute a draft of the plan, that is, a proposed plan. The compiling and publishing may be carried out by the planner or by a small subgroup of the citizens committee. Citizens usually distribute the plan, making an effort to provide a copy to every household in the community.

To increase the potential for implementation, the plan must develop over time in the minds of people—not just be presented in a final publication. To help accomplish this, the vocabulary of the plan should be that of the client—not that of the academician or scientist. This advice does not imply that either vocabulary is better, but only suggests that if the plan is to be implemented by the people of the area, then the language of the client should be respected and used. The layout and design of the report is equally important. It should be designed for ready reference to and clear illustration of specific recommendations. Each chapter should be complete and self-explanatory, covering one subject from inventory to recommendation to implementation. A summary reviews the contents of each chapter for the reader’s understanding.

IMPLEMENTING THE PLAN

The best plan is of little value if it is not followed by effective implementation. When governmental bodies are involved, four groups are responsible for implementing an adopted plan: elected officials (board of commissioners or select persons), the planning commission, the conservation commission or other citizens committee, and special-project committees, which may include an implementation committee or a joint partnership between a community-based organization and the appropriate political jurisdiction.

Elected officials shoulder most of the responsibility for implementing an adopted plan. State legislation establishes their duties. Among other responsibilities, the elected officials enact subdivision regulations and zoning ordinances and adopt a capital program and budget.

The planning commission may be advisory or may have its responsibilities delegated by elected officials. The planning commission deals with the myriad details of land use, including drafting subdivision regulations and zoning ordinances, setting conditions for development, and making recommendations to elected officials on all aspects of plan implementation. They should be acquainted with the methods of guiding land use listed in chapter 15 and should select the type needed for each step of implementation.

A separate special commission (or subcommittee) may be appointed by the elected body for the specific purpose of assisting it and the planning commission in developing and implementing an environmental plan. In New England this role is frequently filled by a conservation commission. Conservation commissions were introduced in Massachusetts and later sprang up in other northeastern states.

Special project committees are ad hoc subcommittees appointed by the elected body or the planning commission to assist in implementing a single project or goal. The Indian Brook Reservoir project discussed in chapter 1 is one example. Another is a citizens implementation committee or an advocacy group like the one described later in Chapter 5.

Implementation usually consists of three distinct actions. The first and most important is identifying and adopting specific implementation procedures. The second is for the appropriate jurisdictions to enact bylaws or ordinances to achieve the plan’s goals. In small towns or villages implementation strategies often include zoning or a permit system with districting, subdivision regulations, an official map of the planning area, and a budget and program. In more sparsely populated areas, or in natural resource areas, only some of these elements are usually required. The third action is delegating the responsibility of evaluating implementation to the planning commission, a citizens advisory committee, or a community organization.

ADOPTING IMPLEMENTATION PROCEDURES

A plan is only as good as its implementation. The methods for implementation should be contained in the plan itself. One approach is to lay out a grid with goals, time frames, responsible entities, and resources so that progress can be tracked. Another is to include in each chapter of the plan what resources are available and what entity will be responsible for implementation objectives. For example, a proposal for a cross-country ski trail network may include a statement concerning the type of agreements to be worked out with landowners and the persons to negotiate the agreements. Another proposal, for establishing group credit for property owners served by an irrigation association, may indicate the source of funds, the procedure for obtaining funds, and the person(s) responsible for obtaining them. Information on procedures provides the tools crucial to plan implementation.

ENACTING ORDINANCES OR BYLAWS

When ordinances or bylaws must be enacted for plan implementation, it is helpful to draw up a map showing the various districts or zones within the plan area and defining the uses to which each will be put. Community ordinances or bylaws should include subdivision regulations for new housing or for commercial or industrial development. The local government should also adopt a long-term capital program and a more detailed short-term capital budget. Performance-based zones or alternatives such as permit systems—as opposed to the traditional land-use zones of urban areas—can make zoning more acceptable and enforceable in rural areas. When unduly detailed zoning is enacted in rural areas, it can lead to frequent zone changes or to a pattern of granting exceptions on request. This can destroy confidence in the planning process and in the notion of equitable administration.

Where land-use controls or guidelines are necessary, all methods should be considered and the most acceptable selected. Alternatives to zoning include building codes, plumbing codes, health regulations, setback ordinances, easements, and a building permit system.2 In a rural area whose citizens are opposed to zoning, the rural plan should not rely on that method of implementation.

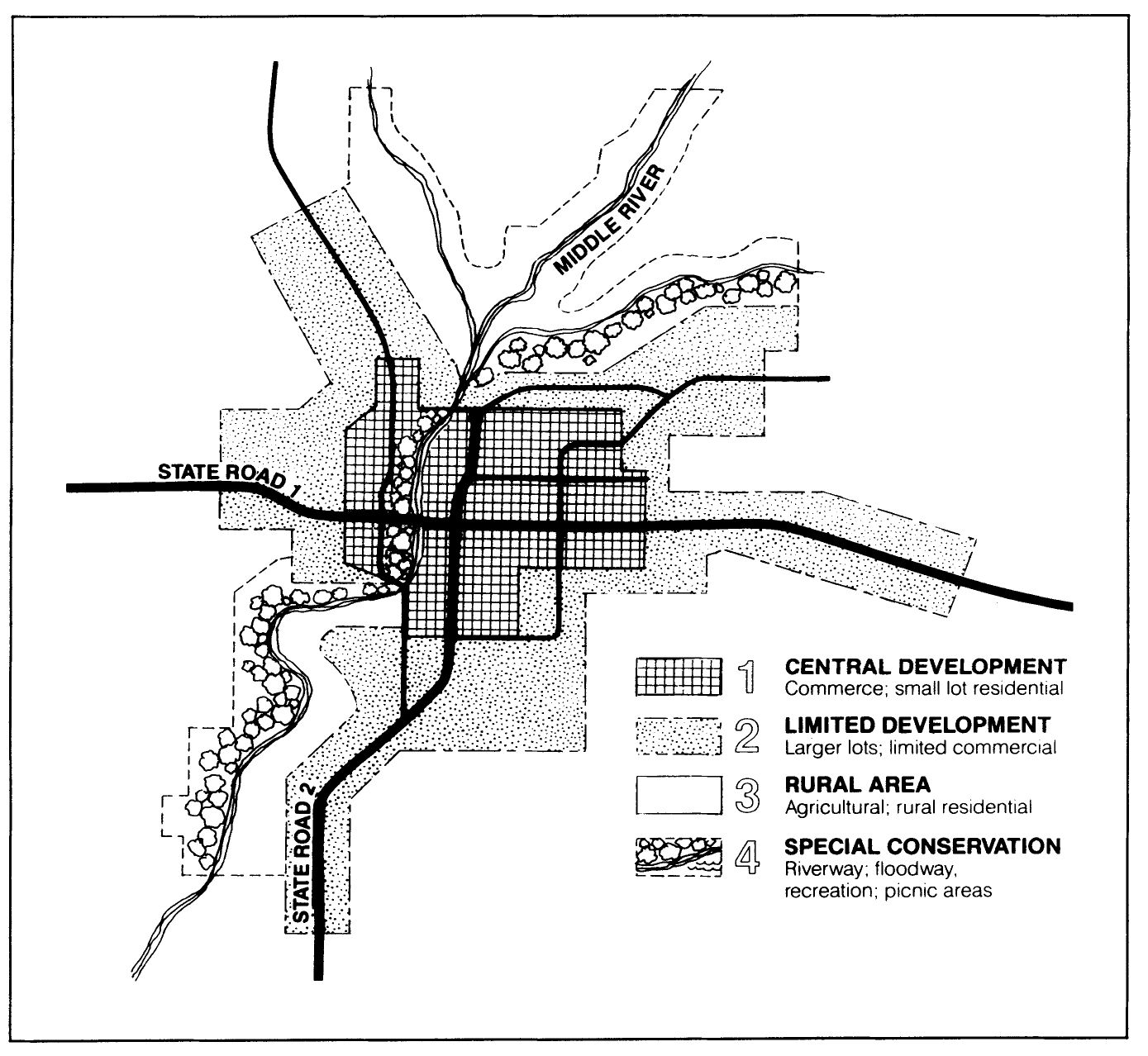

The adoption of simple, clear, functional zoning and subdivision regulations is one method of implementing a plan. Zones or districts should be designed to fit the rural territory and its requirements. There are three important zones for rural environmental planning. The first is the central activity or development zone. This is an area around the village or community center where commerce and small-lot residences are encouraged. Second is the ring around that center, a limited development zone where lot sizes may be larger and efforts are made to avoid commercial development. Third is the rural zone, the surrounding area where lots are sized to protect agricultural land, forests, or wetlands. The rural zone may contain or be surrounded by conservation zones in which building is not permitted if it would damage the environment. Conservation zones may consist of higher elevations, stream banks, lake shores, arroyos, ditch-irrigation systems, wetlands, steep slopes, or ridges. These zones often cross or weave through the other zones.

In urban areas the official projected land-use map is an indispensable tool for implementing a master plan. In rural areas a land-use map is less useful, as it assumes definitive knowledge of the rates and type of future development. Prediction in rural planning is very speculative. A general map, though, showing development and conservation zones and major access roads, does provide a clear framework for a rural area and can help participants make more detailed decisions about future growth.

FIGURE 3.1. Rural Zone Map. The components of this zone map are typical for a small rural community. General areas defining residential density, commercial or industrial use, rural or agricultural districts, and special open or conservation areas, as well as major access roads, serve as a guide for more detailed decisions in the future.

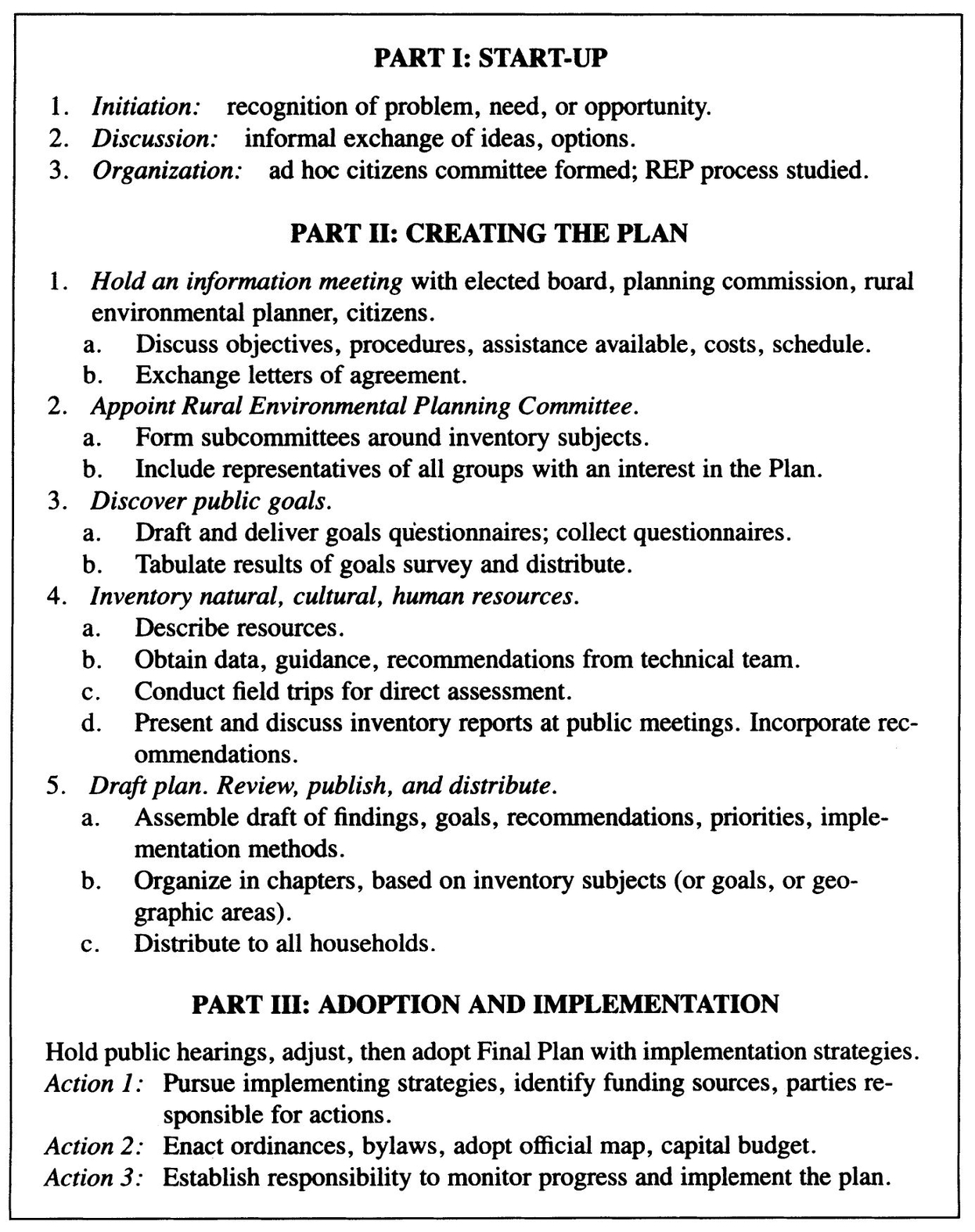

FIGURE 3.2. The REP Process

A capital program sets forth the long-term capital expenditures anticipated by a municipality or a rural planning district. A capital budget establishes specific expenditures for a projected period, usually five years. Proposed expenditures are based on findings for needed physical improvements in such areas as transportation, public facilities, utilities, and land acquisition. The capital program and budget establish commitments for public investment in accordance with the specific goals and needs identified in the plan. As such, they prevent haphazard public spending and block the potential for selectively ignoring established goals. Although detailed programming for a five-year budget may require special assistance, every rural community or individual unit in a planning district should prepare a capital program and budget as a guideline for public investment.

DELEGATING RESPONSIBILITY FOR EVALUATING IMPLEMENTATION

When people are directly involved in defining goals and strategies, implementation is much easier. Participation creates a sense of owning the plan; it creates a constituency. Still, after the plan is adopted and the ordinances or bylaws are enacted, participants must make sure that action takes place. Often the planning commission or REP committee develops a sense of responsibility for, or feels it has a special stake in the implementation of, the plan. Involvement of such citizens in a conservation commission or on the planning commission can provide continuity and help to implement the plan. Plan implementation is aided by clear declarative statements in the adopted recommendations, by effective ordinances or bylaws, and by minimizing the number of variances granted.

CONCLUSION

REP differs significantly from conventional urban planning in both organization and process. The organization recommended in REP includes a working relationship among three parties: the client (a town or county government, a tribe or Indian pueblo, a community-based organization, a multijurisdiction, or a regional board); the planner (a faculty member or a student in rural planning at the state university, a rural-planning graduate, a state agency, or a paid or volunteer professional); and the technical team (personnel from state or federal agencies, private-sector volunteers, or other professionals).