7

Keeping Land in Agriculture

THERE ARE MANY commonly recognized motives for keeping land in agriculture: economic, cultural, and environmental. Even the aesthetic quality of open farmland is an incentive to retain land for agricultural use. The varied topography and textures of rural landscapes across North American farms provide interesting patterns, colors, and tones—pastures, fields, orchards, woods, fence rows, gardens, picturesque farm buildings and homestead lots. Techniques to preserve farmland are outlined and compared in this chapter.

NATIONAL PERSPECTIVE

In America public action to support family farms goes back to Thomas Jefferson and continues in the expression of goals in many state and community plans. Social scientists have long confirmed that communities that are made up of a variety of small to large farms have richer social interaction than communities dominated by only large corporate farms. On a national level, the conversion of prime farmland to nonagricultural uses takes away land needed for the food supply of future generations. Once farmland is converted to more intensive development, the process is considered irreversible.

Many interest groups support public policies intended to preserve farmland. Farmers located near cities would like to continue farming where it is most profitable—close to urban areas. Farms close to cities, though, are located in markets where competing demands for land are the most intense. Many urban residents desire locally available fresh fruits and vegetables; however, to increase community self-sufficiency in food production requires maintaining truckcrop farming near population concentrations. Conservationists also see advantages in maintaining agricultural land: it is a way of providing wildlife habitats and protecting ecological cycles. Knowledgeable taxpayers realize that it costs more to provide services to and maintain most residential developments than they yield in taxes. When agricultural land is turned into housing developments, tax bills rise.

There are other concerns as well. Landowners want to maintain their right to cash in on the increased value of agricultural land caused by urban growth around them. Recreation interests believe that the public should benefit from special tax policies that favor agricultural land. Such benefits include the right to recreational activities such as hunting, hiking, and fishing.

But tax and other incentives do not always produce the desired results or benefits. Since the 1930s, in spite of continuous political pronouncements in favor of preserving the family farm, federal laws in the United States have had an opposite effect. Federal farm policy has favored farmers with larger holdings, allowing them to purchase adjacent small farms. During the late 1970s and early 1980s, tax laws encouraged non-farmers to buy farms as tax losses. Thus further reducing the ranks of small and moderate family farms. The net result of the last fifty years of federal agricultural policy has been a continuous decline in the total number of small to moderate-sized family farms in America. By contrast, many Canadian provinces implemented laws and programs to maintain family farms, and at least one U.S. state, South Dakota, prohibits corporate farming.1

A significant obstacle to keeping land and small farmers in agriculture has been the ineffectiveness of traditional zoning methods. Often considered the only method of solving the problem, zoning is subject to change when economic forces are sufficiently strong. Those who would profit by a change in zoning from agriculture to development usually succeed in obtaining the change. Planners must look for zoning methods that satisfy voters, taxpayers, and landowners. Landowners should not be deprived of the potential for increases in land value, and the taxpayer should not be burdened by inefficient development or an inequitable allocation of taxes. Ideally, preservation methods must allow agricultural land to remain economically productive as long as possible under existing land-control institutions.

TECHNIQUES FOR RETAINING FARMLAND

For many years tax incentives have been used to keep land in agriculture. Most of these are income tax credits and preferential tax assessments of real property, where greenbelt land is taxed at agricultural value instead of market value. In addition to tax relief, a number of other techniques have been proposed and implemented. If in the development of a rural environmental plan alternative techniques are analyzed and compared on the basis of public and private cost, and of political and social acceptability and permanence, a technique, or more likely a combination of techniques, may be found to retain a significant amount of prime land in agriculture. Techniques from which to choose are described below.2

RESTRICTING SUBDIVISION DEVELOPMENT TO SEWERED LOTS

Municipal and county subdivision regulations may require that all duplex, apartment, or mobile home park construction take place on municipal sewer and water lines. Although not effective in restricting single-family dwellings using septic systems or composting, or cluster-home package-treatment systems, this technique allows the planning commission to control more intensive suburban expansion. This limits leapfrog development in open country and allocates the concentration of development in urbanizing areas. While this method can be effective, it has not been widely used by rural towns. Sprawl occurs slowly and is often not recognized by the community until it is too late to remedy.

CONSERVATION ZONING

A conservation zone may be included in a zoning ordinance to restrict building in areas subject to flooding, on steep slopes (greater usually defined as gradients greater than 15 percent), along stream banks, on wetlands, or at higher elevations. Agricultural or recreational uses are permitted in designated conservation areas. The extent to which this technique keeps land in agriculture depends on the percentage of agricultural land that falls into one of the protected categories. In rural areas where a considerable portion of the farmland lies within a defined floodplain, conservation zoning protects much of the prime agricultural land from unwarranted development; in other places, only a small percentage of land is covered. One benefit of this technique is that it can protect public health by protecting water supplies for all users during floods. Protecting public health is an acceptable criterion for land-use zoning. Conservation zoning for flood hazard areas can be justified on this basis alone.

CLUSTER DEVELOPMENT

Clustering keeps land in agriculture by requiring that all buildings be concentrated on a specified, proportional area of a total acreage. To be effective, this requirement should rate building sites according to some functional criterion such as soil suitability for on-site sewage disposal, degree of slope, or the erodibility of soil. The clustering provision in a zoning ordinance should indicate the maximum number of building units per acre. Bylaws can be adopted by the local jurisdiction that set aside one-half or more of a parcel for agricultural use or open space while still allowing the same number of lots that conventional subdivision permits.3

For example, cluster zoning could require a minimum of ten acres for a development. The prospective developer may be restricted to building on only 25 percent of the acreage and only on a portion of the land with permeable soil or some other specific criterion. Approval may depend on development rights on the remaining land being dedicated to the town or county jurisdiction. The land not built upon could thereby remain in agriculture or be kept open without being a burden to other taxpayers. The seller, meanwhile, would still receive full value for the land.

TRANSFERABLE DEVELOPMENT RIGHTS

This technique prorates development rights equally to all landowners, for instance, one development right for each dwelling allowed by the existing zone. The planning commission publishes a schedule showing how many development rights are required for each type of development throughout the municipality. For example, if 1 development right is required for each housing unit, then a person wanting to build a 200-unit condominium would be required to have 200 development rights. If the particular area proposed for development had only 100 development units on the land, the developer would have to purchase 100 TDRs from other landowners within the TDR area. Hence, the total amount of development is controlled and all landowners have development rights to sell or use. This procedure calls for accountability, management skills, and flexibility in planning.

Great interest has been shown in this technique, as it controls growth while allowing landowners to profit from the sale of development rights. Experience with TDRs demonstrates that they are applicable in urban and surrounding areas where land is synonymous with “developable space” and the principal land value determinant is location. The TDR process is less applicable in rural areas where land is not in short supply or where much land is unsuitable for development because of location or topography.4

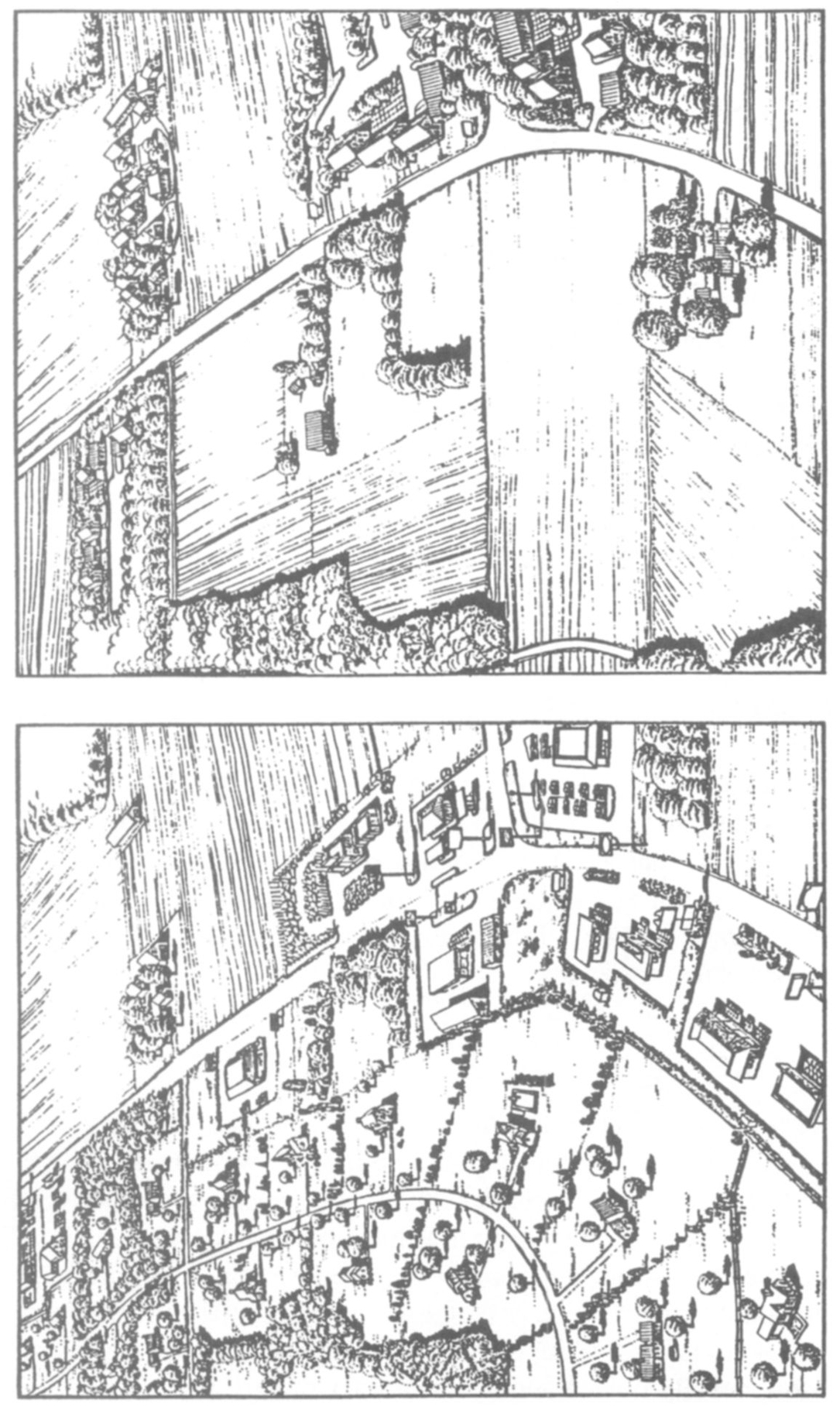

FIGURE 7.1. Clustering Development to Preserve Farmland. The site drawing, left, depicts a conventional approach to development where infrastructure enroaches on and breaks up agricultural land. The other drawing shows how clustering can guide development so that density is achieved with minimal intrusion into surrounding farmland and greenbelt spaces. (Courtesy of and copyrighted by the Center for Rural Massachusetts, University of Massachusetts; design by Dodson Associates, Kevin Wilson, illustrator.)

SCENIC EASEMENTS

A scenic easement is the acquisition by purchase, dedication, or other means of the right to an unhindered view at a particular location or over a certain area of land. This may include purchasing development rights and restricting advertising signs or other obstacles at strategic locations to protect views. Scenic easements have been used effectively in Wisconsin to protect the scenery along the Great River Road, which runs parallel to the Mississippi River. Maine passed enabling legislation for conservation easement in 1970.

Even though the most common use of scenic easements is to preserve vistas, on some sites this method may require the purchase of development rights on wide strips of agricultural land so as to protect it. Scenic easements should be considered for floodplains along major rivers where their combination with flood protection reinforces their benefit to the public.

AGRICULTURAL ZONING

Agricultural zoning has been used by many states to keep land in agriculture. This technique works well until economic pressure builds to the point, for example, that a prospective buyer and the landowner demand a zone change. Experience shows that zoning is effective only if it is associated with accountable tax appraisal, that is, land is appraised at a value consistent with its legally zoned uses, not at a value based on more intensive, speculative use. Agricultural zoning can be effective for the period of time required to develop a more permanent procedure.

COMPENSABLE REGULATIONS

Compensable regulation is a technique that lies between conservation zoning, which may be too confiscatory, and public acquisition, which may be too costly. Compensable regulation limits the use of land, say, to open space but also compensates the owner for any drop in value attributed to the regulation. Under compensable regulation, a greenbelt may be designated as part of an overall plan to enhance the productivity of agriculture as well as to maintain its aesthetic quality. Land use in the greenbelt is restricted to farming, recreation, or other low-density uses. Landowners are guaranteed that if they wish to sell their land, they will receive an amount equal at least to the value of the land before the imposition of regulations, or equal to the new market price of similar land not under restriction. The government obligates itself to pay the difference if the actual sale price falls below this evaluation. Land subject to compensable regulation remains in private ownership, continues to yield tax revenue, and requires no public expenditure for maintenance. The political jurisdiction is required to pay only when a parcel is sold, and then only for the amount of the difference between the sale price and the guaranteed price. Compensable regulation is not a suitable method of protecting a whole rural area, but it is suitable for specially valued and designated scenic areas.

TAX STABILIZATION CONTRACTS

Some states, for example, California, New Hampshire, and Vermont, have developed tax relief programs authorizing restrictive agreements where a landowner receives a preferential tax assessment in exchange for a written contract to retain farmland in agricultural use on a long-term basis. The particulars vary from state to state and sometimes county to county. The Vermont program was enacted in 1967 when the state legislature passed a bill allowing towns to contract with farmers to stabilize their taxes. In Vermont, towns may stabilize the tax rate, the tax appraisal value, or the dollar amount of the tax. The tax stabilization program can be initiated by a favorable two-thirds vote at a town meeting. Elected officials then negotiate contracts with farmers who wish to participate. A number of Vermont towns have implemented this program. Some towns have opted for each of the three stabilizing procedures.5

Several conclusions can be drawn from experiences such as Vermont’s. First, the program is useful in a town with a small number of farms and a large number of citizens who appreciate keeping land in agriculture. In a town with much farmland the program is not likely to be adopted for tax stabilization implies that the tax burden will be transferred. In a rural area made up largely of farmers it would not be equitable to transfer farmers’ taxes to a small group that did not farm. Second, tax stabilization is a holding action. It may not keep land permanently in agriculture. It may, however, keep it in agriculture until other methods of so doing are developed or become acceptable. Third, the towns in Vermont with tax stabilization have not experienced a significant tax transfer. This is because farms in that state are generally assessed according to agricultural productivity, even though Vermont statutes require that land be taxed at fair market value.6

PUBLIC PURCHASE: RESTRICTING AND RESALE

Agricultural land may be protected from conversion by public purchase in fee simple. After purchase, the government agency sells or leases the land on the open market, in this case, for farming purposes only. This can be an effective way to supplement other methods of maintaining land in agriculture.

An experiment of this type was carried out in Saskatchewan, Canada, in the 1960s. In an effort to promote family farming, a land bank commission was established. The commission was authorized to purchase agricultural land of any quality and resell it in viable units to small or new farmers. During the course of the experiment the commission purchased 517,000 acres and subsequently leased 1,400 acres to farmers. It charged tenants an annual rental fee of 5.75 percent of the property’s value. This program permitted a new generation of farmers to get started in agriculture without mortgaging their future. To enhance the economic effectiveness of the program applicants were restricted to families whose annual income had averaged $10,000 or less over the previous three years and whose net worth was not greater than $60,000. Thus the program served people who would not otherwise be in farming. In contrast to many U.S. farm programs, this one, the “state land development corporation” program, was designed to assist the lower-income farmer rather than the large-scale or corporate farmer.

FLOODPLAIN ZONING

Agricultural land can be protected by the local jurisdiction through floodplain zoning. Protecting floodplains means protecting public health, a justifiable aim. There are three possible steps to zoning a floodplain. First, obtain a soil map that delineates flood-prone areas from the local SCS office. Transfer this information onto a planning map. Two, inspect the floodplain in person to see if it corresponds to the locally accepted notion of what floods cover. Three, draft a zoning regulation stating the permitted uses of the floodplain—agricultural, no buildings, and so forth.

PRIVATE LAND TRUSTS

A private land trust is a nonprofit corporation whose objective is to hold land for the particular purposes of the trust. Some land trusts are established to hold land in an open and natural state. The land trust concept can be adapted to protect agricultural land by purchase of development rights from farmers. The Maine Coast Heritage Trust is an example. It was founded in 1971 for the protection of Maine’s coastal islands. Land trusts of this type work well when public interest in maintaining agriculture for aesthetic or environmental protection reasons is high and the number of operating farms is low. Such land trusts have been effective in the hilly tourist areas of northern New England and New York.

LAND EVALUATION AND SITE ASSESSMENT

The LESA is a program developed by the SCS to help to implement the federal Farmland Protection Policy Act of 1981. The program basically assists local governments in protecting farmland. The importance of LESA is that it is not a system of regulations but rather a tool for rating the relative value of land in terms of agricultural potential. Land evaluation helps local government planning commissions and elected officials to identify lands with present and future agricultural value.

Site assessment consists of helping local officials to evaluate the impact of proposed development on an agricultural tract. Assessment criteria, developed by local decision-makers, include such considerations as the size of a site, its existing or potential agricultural use, the agricultural infrastructure, land-use regulations, the availability of alternative nonfarmland, transportation networks, water and sewer lines, and environmental factors.

LESA is not a method of regulating development but rather an information system that establishes comparative values. Each local government decides which land and soil classifications to apply to an area based on relevant technical information obtained from the SCS. In addition to scientific data, local representatives are free to include other criteria they consider important as individual development plans come up for review: proximity to a city, environmental effects, and traditional values, among others. Each factor is awarded points that are then converted according to a weighting scheme; the result is a factor score. Site assessment points serve as one more piece of information for planning and zoning commissioners to use in deciding whether a specific site should be approved for nonfarmland development. Information regarding the uses of LESA may be obtained from any SCS office.

Apart from specific techniques to preserve farmland adjacent to urban areas, where pressure to convert land to nonfarm use is greatest, mention should be made of a strategy to maintain farmland in less threatened locations: keep current land in active production and convert potential farmland to productive use by trying new agricultural products that generate jobs and increase local incomes. Regulation of land use to protect agricultural holdings is not a substitute for working directly with farmers and ranchers to increase the productivity of their land.

As reported recently in Growing Our Own Jobs, projects involving vineyard development in rural Tennessee, specialty vegetables in Mississippi, a hydroponic greenhouse in Georgia, and shiitake mushrooms in Iowa have demonstrated how alternative crops can diversify production, open new markets, increase crop yields per acre, create jobs, and stabilize local economies. Other projects—beef jerkey processing in North Dakota, a wool mill in Pennsylvania, cucumber and pickle processing in Texas, and a corn wet-milling plant in Minnesota—serve as examples of how agricultural products can be processed on-farm, adding value to the products, capturing a larger percentage of consumer dollars, and growing new jobs at home.7

COMPARISON OF METHODS

Keeping land in agriculture requires judgment; options must be compared and related to planning principles. The state’s political and legal framework, public attitudes, and regional agricultural, economic, and land-use trends must also be considered. The suitability of methods for keeping land in agriculture varies according to many factors: the intensity of the trend toward nonagricultural land use; land productivity; income levels of people in the area; level of understanding, experience and sophistication in planning; skill and leadership of people in government; and public attitudes toward land-use control. A technique such as restricting development to sewered lots would be most applicable in an urban setting or in an adjacent area subject to the pressure of urban expansion. Public purchase may be more feasible in a large metropolitan state than in a small rural state. Conservation zoning applies more to areas with many part-time farmers. Tax stabilization contracts are useful where the total number of farmers in a village area or township represents a small percentage of the citizenry. Easements are applicable in special situations, such as a river basin parkway or flood damage reduction.

Above all, no single technique is sufficient to protect farmland in any given community or state. Effective programs should incorporate various measures to maintain and support the economic viability of agriculture. Land-use controls and incentives by themselves are not sufficient. The loss of farmland is the result of many factors, and any attempt to further curb it should be multifaceted, comprehensive, legally defensible, and tailored to local conditions.8

In several REP projects the comparison of methods for keeping land in agriculture has been useful and effective. It has led to broadened discussion of alternatives for enhancing agricultural viability and, in several cases, to specific action to stabilize agricultural land use. For example, in Colchester, Vermont, this type of analysis resulted in the zoning of prime farmland for agriculture. In Charlotte, Vermont, a university planning class provided information that prompted the town to adopt a tax stabilization program for farmers. In South Burlington, Vermont, an agricultural land analysis strengthened the concept of containing development in already developed areas and reducing strip development in agricultural land and related open spaces.

CASE: RIO ARRIBA COUNTY, NEW MEXICO

Rio Arriba County, in the north-central part of New Mexico, is characterized by magnificent mountains and narrow, stream-fed valleys.9 This sparsely settled county covers 5,856 square miles. Its estimated population in 1988 was 32,600. Española is the only incorporated city in the entire county. In the rest of the county there are only two incorporated villages, Chama, near the Colorado border, and Dulce, headquarters of the Jicarilla Apache Reservation. The county does not have jurisdiction over the reservation. With mountain elevations ranging from 5,600 to more than 13,000 feet, and with both natural and manmade lakes, Rio Arriba County, especially the Chama area, attracts visitors, fishermen, and hunters. Some efforts were made to establish resort and second-home subdivisions in Rio Arriba County in the 1960s and 1970s; however, much of this activity was suspended by federal and state authorities because of fraudulent sales of lots.

From the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s, state revenues from extractive industries and federal spending decreased throughout New Mexico. State policy during this period was to promote tourism and other potential sources of revenue. A number of proposals were made, including the development of a major ski resort in the Chama valley. Some ranchers considered subdividing all or part of their property to capitalize on the ski resort.

Under New Mexico law, water resources belong to either the state or prior users. Prospective developers must acquire water rights as part of the property purchased or from other properties in order to obtain approval for the development. Water rights can also be sold separately from land. To sell water rights, though, means permanently severing them from the land, diverting the water from its present use, and retiring any irrigated agricultural land from cultivation forever. For many long-time residents traditional agriculture provides subsistence and preserves cultural roots. Diversion of water to other uses is seen as a threat to economic and cultural survival.

In Rio Arriba County many subdivisions were developed before stringent environmental controls were enacted under the New Mexico Subdivision Act in 1973. Some illegal subdivisions were also developed after the 1973 law. Subsequent to the installment of these poorly controlled subdivisions, evidence showed up of increasing groundwater contamination.

In 1986 the Rio Arriba County Commission amended their existing subdivision regulations in order to strengthen control of land subdivision and to prevent the loss of agriculture. The subdivision amendments declared one of the public interests of the county to be preserving agriculture through traditional community ditch irrigation.

The new regulations require a water system for each proposed subdivision, putting the burden on the developer to obtain rights to sufficient water for all the planned lots. Water rights are allocated by the state engineer’s office, however, and the state engineer must consider the public interest of all affected properties in deciding on the transfer of water rights from one area to another.

Rio Arriba County also developed strict regulations for liquid-waste disposal, requiring larger lots for septic tanks in areas with poor soil or a high watertable. These regulations require the preparation of sufficient information to allow the county commission to determine whether a proposed development will disrupt traditional rural communities and the county’s limited supply of irrigated agricultural land.

CASE: DOÑA ANA COUNTY, NEW MEXICO

Dona Ana County in southwest New Mexico is the state’s second most rapidly growing county, with a population estimated in 1987 at 128,800.10 Las Cruces, the county’s burgeoning city, population 54,100, is home to New Mexico State University and is relatively close to the White Sands Missile Range. Las Cruces’s mild winters have also made it an attractive place for retirees. To accommodate new growth Las Cruces recently engaged in some intricate land exchanges with the city of Albuquerque and the Bureau of Land Management-(BLM). The trades enabled Las Cruces to nearly double in size through planned annexations. The rush for urban expansion made the sale of prime agricultural land attractive to some area farmers.

Immediately to the west of Las Cruces, along the lower Rio Grande Valley, is the town of Mesilla, an historic village with low residential density and extensive farmland. Some in Las Cruces see Mesilla as an attractive bedroom community, and Mesilla is feeling the pressure of that city’s expansion. Many people in Mesilla dislike the prospect of becoming a suburb and would like to keep their agricultural land under cultivation. The town developed an innovative plan to accomplish this.11 The plan draws on precedents in the area involving land trades with the federal government.

The BLM controls land on the urbanizing fringes of Las Cruces, dry, agriculturally insignificant alluvial mesas above the irrigated valley. The BLM plans to release this land for urbanization. To retain its farmland Mesilla has proposed a scheme to utilize the BLM land as a “receiving area” for development rights that Mesilla farmers own in their own lands presently under cultivation. The scheme, for example, would have a farmer in the Mesilla area with a 40-acre pecan orchard, located on prime agricultural soil (as identified by the SCS) and with attendant water rights, voluntarily exchange urban-use development rights on his/her farm for a tract of land on the mesa. The mesa land, now owned by the BLM, has no agricultural value; identified by the BLM and by the State of New Mexico as being suitable for urban expansion, it is scheduled for public sale. The value of the land received by the farmer would equal the difference in value between the farmer’s value per acre for farmland and its potential development value per acre, as determined by independent appraisal.12

Once the exchange is completed, the farmer would continue to own the farm and use it for agricultural purposes. The farmer can also sell it at any time as a farm, for as much as the market will bear, but the deed excludes urban use. The land area of the farm would remain under private ownership; however, development rights would be included as part of a prime agricultural trust for the benefit of current and future New Mexicans. The farmer also owns a parcel of mesa land that can be put to urban use. Such use would have to be approved by federal, state, and local officials. The farmer retains the option of developing this land, selling it for urban use, or holding it for later development.

The federal government does not give away its land; it must be compensated for the market value of any property released. To compensate the BLM for releasing its land, Mesilla proposes to set a transfer tax at a percentage of sales price. The tax would be applied to each sale of mesa land that had already been exchanged for agricultural development rights. The government would then have a steady, long-term source of income to compensate it for the public lands used in the exchange. In addition, a local tax can be applied to each sale for the express purpose of supporting the development of an areawide infrastructure.13

Mesilla does not have the authority, under current state enabling legislation, to levy an additional gross receipts tax for the purpose of paying the federal government. Thus the town needs to find an alternative source for payments. Town planners and officials are publicizing their proposal to state and congressional officials to get support for an additional tax. They also want to present the proposal as a model to be followed in other areas of the country where farmland lies near federal lands scheduled for release.

The town of Mesilla believes that those government entities that would participate in the original exchange of development rights would also benefit from increased land values resulting from future sales. Farmers would be compensated for maintaining agricultural lands in a voluntary system combining free-market principles with land-use planning that respects long-term public goals. The local governments of Mesilla and Las Cruces would thereby gain a new means of “mining” the land and have a perpetual land bank as their source of income. Developers would have a clear idea of where and how urban growth is supported by the government. Agriculture in Dona Ana County would continue to benefit the people. Planning by local government would recognize defined agricultural areas and protect important natural resources, and officials would have a clean slate on which to plan urban growth on the mesa.14

CONCLUSION

These techniques for keeping land in agriculture, with all their variations, have one characteristic in common—to implement them, they require strong public support and a high level of planning expertise. Public support grows as understanding develops of the reasons for conserving agricultural land. Experts who can help to nurture public understanding can be found at the agricultural extension service, the department of agricultural economics or planning, the department of public administration at the state university, or the state department of agriculture. If all of these techniques for keeping land in agriculture are studied and appraised, a method or a combination of methods will emerge to meet that goal. It may be, as the two case examples here show, that some new variation of existing methods develops to satisfy local conditions of financial feasibility and political acceptability.