Although home is often perceived as a private refuge, it can also be one of the most effective places to foster relationships—with those we live with, with friends we have over and with the community at large. Rather than merely sheltering us from the elements and holding all of our possessions, our homes are where we grow up, learn from our guardians, laugh with our friends, and argue (then make up) with our loved ones. A home’s structure and the way we choose to fill it are major factors in these moments: A floor plan designed with community in mind might lead to longer conversations, more intimate memories and closer relationships. The homes and people featured in this chapter exemplify many different facets of community building—some prioritize personal growth while others nurture families; some open their doors to strangers as well as friends; and others are actively interwoven with their neighborhoods. At the core of all these community-minded homes is a shared understanding that the seemingly personal nature of the private home always nurtures more than one.

A single flight of stairs separates John and Juli Baker’s business from their home environment. The founders of gallery and retail space Mjölk live with their young children, Elodie and Howell, in the bustling Junction neighborhood of Toronto, Canada. After purchasing a three-story Victorian building located on a busy thoroughfare, the couple enlisted the help of architects Peter Tan and Christine Ho Ping Kong of Studio Junction to consolidate the top two floors into a single-family home and transform the ground floor into a retail space. “We viewed them as collaborators who could take our ideas, expand on them and make them materialize,” John says. Having their boutique and living quarters in the same building has made it surprisingly easy to balance work and family: John and Juli can switch between keeping an eye on the shop and carrying out various household duties, and Elodie loves popping downstairs to interact with customers. Locally sourced materials dominate the home’s landscape, including Douglas fir floors, white oak cabinets and Quebec soapstone countertops in the kitchen. The cabinetry was made with wood instead of veneer and much of the stonework was left untreated so that the materials would improve with age. “The countertops show the most interesting patina effect because you can see where we tend to work: There are dark areas where our hands rest and where we cook. We think this adds life to the home,” John says. “We’re not striving for perfection, as that’s impossible. We simply hope these natural materials show their value as they get more beautiful with age.” Although their home was designed to be highly functional and accommodate their family’s natural movements, John and Juli added a couple of “emotional elements” for enjoyment instead of efficiency, including a hinoki cedar bathtub they love to relax in after putting in long days at work. “Being able to soak in a wood tub after a hard day is a great stress reliever and will add some years to our lives,” John says. “When we think of home, we don’t just think in terms of functional interior design: The moments we have in that space with our family help to shape our ideas.” An area that combines practicality with pleasure is their expansive third-floor courtyard that opens out to the sky and is separated from the house by glass windows. It’s a nice substitute for a suburban backyard and gives the kids a safe space in which to run around and play. “Living in a city where we’re constantly stimulated by noise and energy can feel overwhelming at times,” John says. “Our home is a sanctuary away from the bustle of the city—a place to disconnect from the outside world and be safe to engage in the things that make us happy.” By blending clean and efficient design with relaxing spaces, John and Juli have created an abode that will positively shape their work-life balance for years to come.

In the following essay (see here), we consider the best ways to disconnect at the end of the day when your workplace and home are one and the same.

The blue and white painting is by Junpei Ori. John and Juli are both fond of her work, which is inspired by Scandinavian culture and design.

Some of their favorite books to read to their young daughter, Elodie, are Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak, The Paper Bag Princess by Robert Munsch and Michael Martchenko and There’s No Such Thing as a Dragon by Jack Kent.

John has been studying the craft of Japanese tea ceremonies for some time. He uses a cast-iron kettle, an electric brazier, a mizusashi (clear water jar), a kensui (water container), a chawan (tea bowl) and a bamboo ladle to prepare the tea.

Some of the couple’s favorite culinary items include kitchenware designed by Oji Masanori and a copper and brass coffee dripper by Japanese company Hario.

Switching off from work after hours is difficult when your office is also your living room. Reserving a time and space for other pursuits can help you focus on making the most of both work and play.

For those who work from home, maintaining a separation between the two ways of thinking can seem near impossible. Still, this hasn’t stopped many from trying: Virginia Woolf kept a writing lodge at the bottom of her garden, Mark Twain wrote in a study so isolated from the rest of his house that his family had to summon him using a horn, and Norman Mailer went so far as to construct a “crow’s nest” for writing in his Brooklyn town house—it was separated from the rest of the family residence by a three-story drop and accessible only via a gangplank.

This wasn’t due to a lack of physical space: In all three cases, there was no shortage of rooms inside the houses where the authors could’ve chosen to write. Instead, it seems to hint at the desire for psychological space, a means of drawing a line—or, for Mailer, a vertigo-inducing chasm—between the professional and domestic spheres.

Because it’s so tempting to view the lives of artists, writers, musicians, inventors, scientists or any of the greats exclusively through the lens of their work, we often forget that they also cultivated interests outside of their careers. Even those—or perhaps especially those—who are consumed by their craft need respite from it. Nowhere does this become more apparent than in the home.

For example, Woolf wasn’t only a gifted novelist but also a nature lover with a keen eye for color. This was expressed in her writing through vivid descriptions of the natural world and also in the elaborate garden she tended with her husband at their Sussex home. She described their plot—complete with orchards and several greenhouses—as “the pride of their hearts.” In 1920, she wrote that weeding produced “a queer sort of enthusiasm which made her say this is happiness.”

On the other hand, Mailer was a sports fanatic eager to develop his own athleticism whenever he had the chance. His love of sailing was so great that he had his New York apartment remodeled in the image of a ship’s cabin, complete with a hammock and rope ladders.

Meanwhile, Twain became legendary for his marathon billiards sessions, apparently dedicating up to nine hours a day to the game along with a significant amount of floor space in his Hartford home. He reportedly told a friend, “I walk not less than 10 miles every day with the cue in my hand.” Having designed the house from scratch, he thought of the place less as a structure and more as another member of the family, writing, “To us, our house was not insentient matter—it had a heart, and a soul, and eyes to see us with.”

While these writers’ homes served in part as places to work, they also became places to retreat from it—spaces to nurture and practice the many other aspects of their lives.

Of course, we can’t all afford to turn our homes into shrines to our interests: Budding sommeliers often have to forgo an underground cellar in favor of an IKEA closet full of wine crates, and would-be Julia Child protégés struggle with the logistics of serving a three-course meal on a one-square-foot coffee table. But the idea of creating an oasis in our homes—a place to escape from the daily grind—is one we can all strive for (even if our orchard is just a small window box, or our ship’s cabin is a toy boat on the edge of the bathtub).

Ultimately, when we’re able to switch off and leave our jobs at the door, we allow ourselves to put on our other hats—of friend, roommate, parent, partner, cook or gardener. These roles may not pay their share of the rent, and their audience may be smaller, but they’re no less essential to who we are. When our house not only protects us from the elements but also fosters the many facets of our identity, that’s when we know we’re really, truly, home.

When Geraldine Cleary asked Brisbane-based firm Donovan Hill Architects to build her home, she had no idea that their humble project—which has come to be known as the “D House”—would win the 2001 Robin Boyd Award, Australia’s most prestigious residential architecture prize. “My house was intentionally designed to accommodate multiple configurations of relationships, activities and events,despite its modest scale,” says Geraldine, a health and social policy researcher. She loves sharing her space with guests and frequently offers up her house as an inner-city venue for friends to host events. “Shared living is an important part of being operative in society and the world,” she says. The house has accommodated various tenants over the years, including Timothy Hill—the lead architect of the D House—and her current lodger, the filmmaker and photographer Alex Chomicz. One of Geraldine’s favorite aspects of her home is the interplay between the inside and the outside—this was achieved by designing the interior and exterior floor heights at the same exact level, extending certain materials to the outside realm and placing skylights above some interior walls, doors and parts of the kitchen, which allows these elements to be lit from above and cast shadows as if they were freestanding outdoor structures. “This creates continuity between the public and private territories, the inside and outside areas, and the domestic and civic realms,” Geraldine says. The high garden walls break down the breeze, light and sight lines so she can also treat the outside space like a room. “I furnish it with things you would normally associate with the interior of a house, such as flowers, upholstery and books, without them being blown around,” she says. The interesting proportions of the house are highlighted by the use of scale: Smaller bedroom doors contrast with larger doors in the rest of the home, and the low and long window near the entrance creates the illusion that the wall it’s set in is much bigger. “Some things are a bit too small and some are a bit too big, and the act of contrasting them engages the imagination,” she says. Light also plays a huge role in creating the home’s overall character—the house and its surfaces are oriented so the light that enters is reflected and therefore never too bright or harsh: The overall effect elevates the existing attributes of Geraldine’s home. “The atmosphere of the house as a whole is calming, uplifting and comforting, and the changes in the light and shadows from morning to night and from one season to the next are sustaining,” she says.

In the following essay (see here), we explore why light has a positive influence on our homes, families and health.

Right: These ceramics were made by Melbourne-based designer Simon Lloyd. Geraldine received them as a gift from architect colleague John Wardle.

The chairs on the far right of Geraldine’s dining room were made by Danish furniture designer Hans Wegner.

The large window that looks out onto the street is made of two sliding components: One is glazed glass and the other is a timber screen. Geraldine often has the screen closed with the glass open on summer evenings, but she slides everything open for parties.

When it comes to the essentials for a happy living environment, having a home flooded with natural light is often at the top of our lists. By tweaking just a few small aspects of our daily rituals, we can improve our relationship with the sun to benefit both our homes and our health.

Every day presents us with all kinds of decisions to make about our lifestyles, and there are plenty of self-diagnosis websites, new age books and mothers-in-law ready to indisputably instruct us on the choices we should be making. In an attempt to better ourselves, we try to obey their mantras: We sleep eight hours a night; we opt for whole grains instead of white flour; we drag our reluctant bodies out for a quick jog; we choose not to open the second bottle of Riesling. But what if there were something more vital affecting our health? One that predated gluten alternatives and spin classes?

For the past few billion years, the sun has reliably risen every morning and set every evening. Our bodies have therefore come to expect its daily spiral through the sky, and most of our biological systems work on the assumption that we’ll follow along with its sunlight-based sequence. But now instead of waking with dawn, we have snooze buttons. Instead of dozing at dusk, we have Netflix.

Sunlight plays an intrinsic role in our lives and has a profound effect on the way we think and how our bodies function. Through its role guiding our circadian rhythms—the internal clocks that keep us regulated—sunlight can control everything from our sleeping habits to our wintertime melted-cheese cravings. By making small changes in both our routines and our homes, we can help our bodies stay in sync.

But how did we lose our connection to sunlight in the first place? Were we complicit in our demise into dimness? When Thomas Edison popularized the lightbulb some 135 years ago, he was unwittingly ending our close relationship with natural light: Thanks to the humble lightbulb, we can now work graveyard shifts and salsa until dawn. Convenience glowed brighter than our biological clocks, and we’ve been slowly letting them fall out of sync ever since.

By synchronizing ourselves and our homes with the sun, we may be able to reconnect with the undulation of the day and its restorative power. Here are some quick ways to fine-tune your light-related habits:

Don’t Hide Behind Glass

They say that people who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones, but they should throw open a window: Just like sunscreen helpfully blocks our skin from certain harmful light frequencies, the glass in windows deflects some other frequencies our bodies need to trigger biological responses. It’s handy that we don’t burn while sitting in a sunlit living room all day, but the fact we don’t scorch should be a clue that we’re not getting all that the sun has to offer. If your home is already configured to let in a lot of light, consider opening a window and basking in it—you’ll soak up more vitamin D without a pane of glass getting in the way.

Observe Dawn and Dusk Outside

Instead of sipping your morning coffee on the couch while the sun is rising, wrap yourself in something warm and perch outside. While there’s plenty left to learn, it’s becoming apparent that dawn and dusk may be the most important parts of the day for us to be outdoors in order to help set our circadian rhythms: The light quality at these times is changing rapidly, and that change is absorbed by our eyes and translated by our brains to serve as a biological cue for whether it’s early or late, thereby orienting our cells to wake up or fall asleep. These effects are best felt by being outside when the sky slowly turns from black to blue and back again. By getting up 20 minutes earlier to walk the dog at dawn or snacking on charcuterie while watching the sun set from your porch, you could be helping your body work out if it should be revving up or winding down.

Black Out Your Bedroom

Sleeping eight hours a night is beneficial, but not if our bodies think it’s daytime. Switching on the bathroom light or checking emails in a bout of insomnia might not be the biggest problem either—the most disruptive factor may be the ambient light pollution drifting in through your windows. To counter this effect, you can either block your windows with heavy curtains or wear a very chic sleep mask—at least no one will be able to see you in the dark.

When it comes to aligning yourself and your home with the light, the most important factor is figuring out what works best for you—even the act of being conscious about sunlight is a step in the right direction. As time goes on and the sun continues to rise and set every day until it flickers out, we will continue to learn how to have a better relationship with it. There’s still so much to discover, but at least we’re beginning to see the light.

Yvonne Koné and Rasmus Juul moved to the Copenhagen suburb of Vesterbro a decade ago because they were inspired by its rich history and historic atmosphere. The apartment building they currently live in with their children—Johanna, Bror and Hasse—was built in the 19th century by the Art Nouveau–inspired architect Anton Rosen and offers a welcomed respite from the rest of the city. “This is where I relax completely with no filters,” Yvonne says. She and her husband, a children’s book illustrator, have watched their neighborhood shift over the years (a recent influx of residents has brought a new mix of families, professionals and young newcomers), and Yvonne feels like both she and their home are changing along with it. “I like things in movement and the feeling that nothing is static,” she says. With half of her brain leaning toward perfectionism and the other half toward what she describes as complete disorganization, the couple’s home is usually redecorated at least once a year. “Painting the walls has always given me the feeling of a fresh start—it’s like a clean canvas,” she says. “I’m not very attached to physical things, and when I’m redecorating as often as I do, I see it more as a form of exchanging rather than consuming—I sell some items and then find a few more.” Whenever she redecorates, Yvonne tries to make the decor minimal and manageable, as having three children and a time-consuming job as a designer keeps her busy as it is. She and Rasmus are fans of their home’s foundation of smooth, clean walls combined with pinewood floors, but she says, “The perfectionist in me has accepted that it’s OK for there to be a little—or sometimes a very big—mess.” The duo also believes that a resident’s personality should be clearly visible in their space. “After looking at a few items in a home, you can tell that someone selected a particular piece for a reason—not necessarily because it was beautiful, but simply because someone liked it,” she says. A possession that speaks to this notion is a set of warm, plush bathrobes that Yvonne gave to the family members for Christmas a few years ago. Along with lighting some flickering candles, wearing the robes has become a household tradition during the dark Danish winters when they function as the family’s around-the-clock loungewear. While the robes aren’t fancy (“Rasmus thinks they’re kind of sloppy,” she says, laughing), they exemplify a sense of comfort that she hopes to keep throughout her home.

Yvonne designed the couch in the living room, the rug is a handwoven Berber carpet from Morocco and the coffee table was found at a thrift store in Italy. Her son, Bror, created the drawings displayed on the windowsill.

The chair in the kitchen is by Danish brand Please Wait To Be Seated. Rasmus enjoys whipping up meals for the family, especially dishes that remind them of their trips to Greece.

Left: Yvonne’s favorite sketchbooks are made by the Copenhagen design company L.A. Graphic Design.

The couple’s children love the spacious feel of the apartment. Rasmus is an avid collector of art books and drew most of the sketches on their bookshelves.

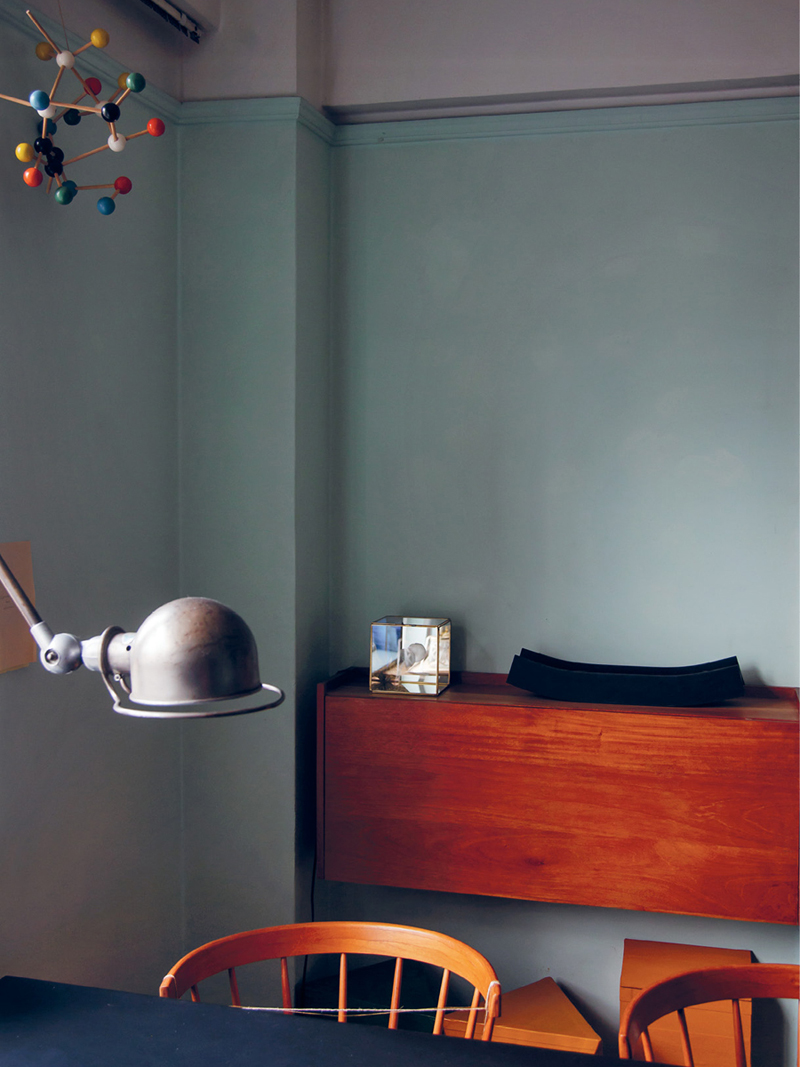

Many of designer and curator Khai Liew’s fondest memories of home are rooted in his childhood residence in Malaysia, which his father built in 1964. “There was a sense of beautiful proportion to the house,” Khai says. “Everything about how it sat on the land felt right: The way my father carved out the space instilled a sense of volume and proportion in me.” At age 18, Khai moved to Adelaide, Australia, where he currently lives with his partner, Nichole Palyga. “We’ve worked together for more than 10 years. Khai designs and I manage the practice, though the roles constantly overlap,” Nichole says. Khai’s formative years as a collector and conservator of early Australian furniture and folk art piqued his interest in the distinctive quality and sense of permanence offered by various types of solid wood, which led the couple to furnish their living space with predominantly wood-based textures. Coupled with the “fortress-like feel” of the home’s exterior, these materials provide the reassurance, security and privacy Khai identifies with being at home. “Our house is an orderly one where everything has a place,” he says. “Each time I open the front door, I can sense the tranquility.” One of the couple’s favorite areas is the central indoor courtyard, which brings light and a sense of space to the house. Khai cooks in the courtyard all year round, so it’s very much an additional living area. “The light there is especially beautiful on a late summer evening,” he says. “It takes on a magical and intense bluish-gray tone, and its calming effect permeates the whole house.” Khai’s work as a curator has trained him to be meticulous and disciplined about what he brings into their personal space—objects are carefully selected and placed alongside each other to create a dialogue in the area where they sit. “The result is harmonious, and in the harmony there is calm and stillness,” he says. Items made by the couple’s friends are also interspersed with Khai’s own work: His designs are heavily influenced by his eclectic cultural experiences and tell stories about his Chinese-Malay childhood and other groups who have migrated to Australia. “I find inspiration in the slightest silhouette, the fold of a skirt, the face of a Japanese bride in traditional dress, the weave in a basket, the flow of Islamic calligraphy or a dancer’s pose, to name a few,” he says.

In the following essay (see here), Khai elaborates on how his multicultural upbringing has influenced his approach to design.

The Adelaide-based artist Helen Fuller, who is a friend of Khai’s, designed the ceramic vases. Nichole picked up the teak box on a trip to Copenhagen, and the teak chair is by an unknown mid-century Danish designer. André Derain painted the artwork on the wall.

A 1930s Japanese gown hangs from the couple’s headboard. The abacus is a piece of 19th-century Australian folk art. Khai designed both the American walnut bedside table and the lamp with a mulberry-bark paper shade.

Top: The two paintings are by Danish painter Johannes Hofmeister and the candlestick holders are by Jens Quistgaard. Khai made the dining table out of European oak and the chairs were designed by Niels and Eva Koppel.

Bottom: The triptych on the wall is by Khai’s friend Jessica Loughlin, a glass artist. Khai designed the chest of drawers and suspects that the easy chair—which has no maker’s stamp on it—is a rare prototype by Jens Quistgaard.

Designer Khai Liew’s Australian home is a space where nostalgia, folk art and contemporary components coexist. Shaped by his upbringing in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Khai’s multicultural influences are evident in both his personal and professional aesthetics.

Home is where I can feel at peace, where freedom can be found and where my memories are. I’ve lived in the beautiful city of Adelaide my entire adult life. I arrived in Australia as a bright-eyed teenager eager to take on new experiences alone in a far-off land. Although the transition posed its challenges, I found happiness and comfort in my new surroundings almost instantly thanks to the strolling distance between my school and the beach. It was like settling into an endless summer, all fish-and-chips and burning feet on hot sand.

I tend to surround myself with things that reflect my history, my encounters and my friendships. My most prized possession is a silk-lined winter jacket that my mother made for me when I first left Kuala Lumpur for Adelaide at age 18. I was brought up in year-round tropical heat, so I had absolutely no notion of the implications of winter. She knew the jacket would be more than something to keep me warm—it also served as a conduit to family memories. Some 20 years later, she mended its worn cloth with much care, keeping both the object and the memories intact.

I’m very disciplined with what I bring into our home. For many years I collected, conserved and dealt in early Australian furniture and folk art, so I’ve spent a lifetime assessing works of great merit and living with them. I surround myself with objects made by good friends—mostly artists working in Adelaide—interspersed with some of my own designs. I’m good at distilling what I don’t want and I’m happy to live with less. I like to group items from different disciplines as if they were conversing, bound by the visual language shared by the artists whose work I collect. These pieces are carefully selected and represent much more than mere decoration: They’re in our house not only because they enrich our lives aesthetically, but also because they’re full of rich meaning.

The meaning behind objects and design is intrinsic to my own practice. I like to tell stories with my furniture designs, such as the 19th-century European migration to Australia or tales of my upbringing in Malaysia. Collaborating with fellow artists brings about a wonderful confluence of ideas and fresh dialogues that explore aspects of the Asian diaspora and the historical, sociological, cultural and physical facets of the Australian landscape.

Although it’s been many years since I left Malaysia, the experiences I had in my childhood home remain a great influencer to this day. In 1964, my father built a Japanese-inspired house atop a hill overlooking Kuala Lumpur. As a child, I loitered around the building site watching the joiners and carpenters use hand tools to fabricate the floorboards, shōji sliding doors and beautiful wooden cupboards, and I imagined how I’d furnish it—I was already busily dreaming and designing. Although there were 11 of us who lived there, it felt like a quiet house. It now occurs to me that my father achieved this by balancing the mass of the house with the employment of negative space, which is the core idea behind the Japanese concept of ma.

This blend of mid-century modernism, the spirit of the Japanese aesthetic and the importance of space, light and materials has always stayed with me. I strongly subscribe to the notions of both sensual design and architecture that places an emphasis on textured natural materials, habitableness and the right light. Wood is everywhere in our house—each piece of furniture feels different and has a distinct smell. The mark of the hand is evident in almost all the things that I live with or make for the house: Whether it’s a porcelain spoon, a wooden ladle or a dining chair, I appreciate that a direct link to the maker can be found through craftsmanship.

Jessica de Ruiter and Jed Lind’s neighborhood provides the perfect backdrop for their relaxed California lifestyle. The former East Coasters live in Silver Lake, Los Angeles, in a 1953 Gregory Ain–designed home with their daughter, James, and an Australian shepherd named Blue. “We love the strong sense of community in our neighborhood and the pride its residents take in all aspects of living here,” says Jessica, a fashion editor and stylist. “It’s filled with a nice mix of young families, creative types and people who’ve been here for generations and have seen it go through immense change over the years.” The family often begins its day with a hike around the Silver Lake reservoir and also visits the running trails, meadows and playgrounds close by. “We like how it’s a bit tucked away from the craziness of the rest of Los Angeles, so coming home at the end of the day feels like a retreat,” says Jed, an interior designer. Their affection for the sunshine and outdoors extends to their home, where they’ve created a seamless flow between the interior and exterior. They also love the way their house was constructed to accommodate the changing sunlight throughout the day: The windows are smaller on the side of the house where the sun rises so it doesn’t disturb the residents, but the floor-to-ceiling windows on the opposite walls let in generous views of the sunset. “We get some amazing golden-hour panoramas from our living room,” she says. Although the property was initially constructed as an artist’s residence and needed a fair bit of renovation to suit a family’s needs, they were mindful of respecting the home’s original design. “We knew that we needed to update the place, but we wanted to restore rather than renovate,” Jessica says. “Gregory Ain’s daughter actually made an impromptu visit during our renovations and told us her father would’ve been proud of what we’ve done, which was a really special affirmation.” Jessica and Jed describe themselves as “intensely visual” people whose creative backgrounds have greatly influenced their decorating choices, from the unique furniture they’ve amassed over the years to the art hanging on the walls. Much of their collection was inherited from Jed’s late mother, who was a keen art collector, while other pieces were acquired from trades with Jed’s artist friends. “Jessica is definitely more traditional and classic in her taste, and I veer more toward modern minimal design,” Jed says. “But we both gravitate to timeless design in both interiors and fashion and prefer to invest in pieces that are going to be with us forever.”

In the following essay (see here), we take a cue from Jessica and Jed’s morning hikes to discover how other creatives spend the day’s earliest hours.

James likes to host tea parties for her stuffed animals. Jed made the table and assembled the chairs from various trips to the flea market.

These fluid ceramic pieces were designed by local artist David Korty.

Elad Lassry took the photograph hanging on the wall and the potted plant is a New Zealand laurel. Some of Jessica’s favorite linen brands include Frette, C&C Milano, Rogers & Goffigon, Matteo and Loro Piana.

Although Jessica and Jed are huge fans of the cinder block and exposed aggregate in their backyard, Jed decided to soften it by planting roses, lavender and olive trees and added beds of boxwood around the pool.

Jessica loves these photographs taken by the Los Angeles artist John Divola. For this series, he went out into the Mojave Desert and took photos of wild dogs while they chased his car.

Making the most of the morning’s predawn hours can be the best way to start the day, whether they’re used for reading, ruminating or romanticizing. By harnessing the time that passes before the rest of the world rises, we can jump-start both our days and our minds.

Early mornings are dark and quiet. Although your warm bed beckons you to climb back in, starting your day before the day can leave you feeling enlightened and ready to meet life’s forthcoming requirements that rise with the sun. It’s not a time to get ahead at work or skim your social-media feed—those can wait, as can the laundry, the shopping list and the call to your mom. These things will get done, but the early morning hours offer you a chance to do something for yourself and should therefore be protected.

Countless early birds have refused to let menial daily tasks bully this golden time. Before entering her studio for the day, Georgia O’Keeffe woke at dawn to the sound of her dogs barking, warmed up with tea and then took a walk. Henry David Thoreau ventured out into the frigid morning to hear the first birdsongs. While his wife slept in, P.G. Wodehouse did calisthenics on his front porch before reading pop fiction over coffee cake, toast and tea.

Others rose early to pursue their passions before beginning their normal life. Sylvia Plath woke at 5 a.m. to write before caring for her two young children, as did Toni Morrison, who raised her two sons while working in a publishing house. (“It’s not being in the light,” she said. “It’s being there before it arrives.”) His days filled with business, Frank Lloyd Wright developed his architectural designs from 4 to 7 a.m., and Immanuel Kant meditated over a pipe and weak tea before heading to the local university to teach science.

Rising at the same time every day can establish a ritual (plus the consistency helps prevent you from giving up). Whether you wake up early to work on a passion project or use that time to indulge in doing nothing, beginning with a routine makes these moments distinct. The night before, prepare your French press or set out your loose-leaf tea so all you have to do in the morning is stumble into the kitchen and blearily boil water. Listen to Glenn Gould’s version of Bach’s Goldberg Variations—or Daft Punk, if you prefer. Or if you crave amore ascetic start, put on a sweater and slink over to you desk without a sound. The morning may be cold, but you’ll warm up as you awaken and devote a fresh and unadulterated mind to your fascinations.

But what if you can’t rouse yourself despite your best intentions? Perhaps you push the snooze button incessantly or decide that no amount of predawn enlightenment is worth the lull you fall into by mid-afternoon. Thankfully, the fullness of life is not proportionate to how early you rise. Proust slept during the day and worked through the night, George Gershwin came home after evening parties to compose music until dawn, and George Sand often left her lovers’ beds to write in the midnight silence that inspired her.

Whether their gravitational pull was toward morning or night, these visionaries all established a daily space for themselves only and refused to let their creative spirits hibernate along with the sun. Their efforts were both large and small, but always deliberate. If all you do is wake up 15 minutes earlier to sip rather than gulp your coffee, you’re opening yourself up to a more intimate life. As the German idiom goes, “The early morning has gold in its mouth.” And who doesn’t want to be dusted with gold?

Artists Delcy Morelos and Gabriel Sierra have transformed their home into a gallery of their own with stacks of books, inspiration boards and sculptures covering most available surfaces—but their style of arranging is intentional and shouldn’t be confused with clutter. “Everything we own has to be useful or at least have an important symbolic meaning,” Gabriel says. “Objects must be arranged by following the geometry of the space, which is shaped by the architecture.” Living in the bustling neighborhood of Las Aguas in Colombia’s capital of Bogotá, the couple has carved out and carefully created a nest amid the surrounding government buildings and offices. “Our apartment is a kind of sanctuary where we escape from the world,” Gabriel says. He and Delcy and have lived in this apartment with their four pets—cats Bacalao and Ratón and dogs Sopa and Plato—since 2001, but the building has been standing since the 1930s. Some of the structure’s history may have even unconsciously influenced their decorative choices. “Sometimes we think our home is composed of information and memories from other houses we knew in previous lives or in parallel universes,” he says. When they moved in, the duo didn’t do any major renovations beyond painting the doors and cupboards with white enamel to help brighten up the space. Instead, they focused primarily on making the space more functional and comfortable by adding bookshelves, tables and chairs to match their needs. Accepting the inescapability of an artist’s never-ending work cycle, they also chose to integrate a workspace into their home: Gabriel has a room inside the apartment for smaller projects like drawing and model-making, and Delcy has a larger studio on the ground floor of the building for her projects. When they need a break, the artists journey out from the facade of their unassuming dark brick building for a walk in the vibrant city center. But they also enjoy spending a lot of time simply pondering and relaxing at home. “I believe the house is an important layer of our personalities through which we discover and dwell in the physical world,” Gabriel says.

In the following essay (see here), we consider the importance of setting aside time to do nothing except stare out the window.

Bottom: A wooden architecture model, an old natural history book and a figurine found at a Bogotá flea market sit on a small table. The larger chair is an Eames design.

Gabriel created the wood screen with a carpenter friend using cloth hinges. It was originally going to be part of an art project, but he ended up using it to divide the living room area from the couple’s library.

The images on the walls are a combination of old postcards and pictures found in newspapers, magazines and books.

Right: Delcy works on a piece of artwork in her studio, which is in the same building as their apartment.

Our homes are often where we unwind by actively puttering around—cooking, gardening, decorating—but it’s also important to take time to gaze out the window and enjoy doing nothing at all.

Seven years ago, I lived in an apartment without an internet connection and a flip phone that worked only to make calls and send 40-character texts. My bedroom had a third-story view of a busy downtown street; it was small, and the bed was pushed up against the window. I’m sure the hours I spent staring out that window would have added up to weeks of time. Without the distraction of the internet or the option of watching a movie, I was certainly more productive, according to certain measures. I watched nothing and anything outside. I drank coffee and (occasionally) smoked cigarettes—two habits that while unhealthy for the body can, in certain circumstances, have health benefits for the soul.

A mind adrift in a sea of its own making is far more interesting than a mind following a trail of hyperlinks. But when I compare those years to now, what strikes me as a greater loss is all the time I spent doing nothing.

It’s the stuff of gods and infants—the birthplace of great works of art, philosophy and science. The habit of doing nothing at all is incredibly important to our individual and cultural well-being, yet it seems to be dying in our digitized age.

Far from laziness, proper idleness is the soul’s home base. Before we plan or love or act or storytell, we are idle. Before we learn, we watch. Before we do, we dream. Before we play, we imagine. The idle mind is awake but unconstrained, free to slip untethered from idea to idea or meander from potential theory to potential truth. Philosopher and friar St. Thomas Aquinas argued, “It is necessary for the perfection of human society that there should be men who devote their lives to contemplation.”

That third-story apartment window enabled such rumination.

When a view is familiar, we can look without registering much at all. On the other hand, because it’s familiar, we know it intimately and are able to register, perhaps by osmosis, the details that others would miss. We perceive the small changes: the first chickadee, the white-brown-green-brown of the year, the new hedge across the street. The window is for distracting ourselves while simultaneously paying careful attention. Both of these opposites enable each other. Author Karl Ove Knausgård noted there’s a strange comfort in “taking notice of the world while we pass through it, [all the while] the world taking no notice of us.”

Is true idleness a lost skill? How often do we sit serenely unoccupied? How often do we walk, as Henry David Thoreau advised, with no agenda or destination, present and free? What an uncommon sight: a solitary individual, his head not buried in a newspaper or laptop or phone, simply sitting—his mind long wandered off.

Productivity is not the only measure of time well spent. Some of the most important scientific innovations and inventions were “happened upon,” unplanned, after years of unproductive, leisurely puzzling. My five-month-old understands this intuitively: He’ll learn an entire language and how to sit, stand, crawl and walk all by doing mostly what may look like nothing to an adult.

The time we spend idle makes for a healthier state of mind. Simpler things bring us joy. We want less and are more at peace when we get it. We sleep better and work harder. When we observe our immediate surroundings, we are more grounded in our context and more attuned to the rhythms of whatever season or home we are in.

For stylist Nathalie Schwer, entertaining is inextricably linked to her home’s identity. “I love the freedom of being able to host people and that my house has become a familiar base to many of my friends,” she says. Hosting gatherings gives Nathalie an opportunity to experiment with cooking different vegetarian meals, and her guests often show up ready to pitch in or bring a delicious offering of their own. “I don’t usually follow recipes,” she says. “I prefer to invent dishes on the spot while I’m shopping for groceries. I’m constantly testing out these creations on my friends.” The Danes love socializing indoors as a natural response to the cold weather and short daylight hours, and Nathalie particularly enjoys opening her home to friends during the winter months: She makes sure there’s plenty of firewood and tea on hand for her guests to while away the evening hours around her fireplace. “Danish people really know how to cope with and structure their activities around the weather,” she says. “Starting in September, you’ll often hear people say they’re looking forward to the opportunity to hang out inside.” Nathalie, who has lived on her own since she was 18, calls a spacious apartment by the waterfront home. Her neighborhood of Islands Brygge is a close-knit community where she’s come to know the people who live around her, such as the local merchants and shopkeepers, and the beautiful setting only makes it feel even more special. “I have an open view and so much greenery around my home, and it’s wonderful to observe how the character of the city changes with the seasons,” she says. When it comes to decorating, Nathalie treats her living space like a workshop and gives herself the freedom to frequently change the layout and furniture in her home. This allows her to experiment and think creatively. “It’s become a bit of a joke within my circle of friends and family, but I love that my house isn’t so delicate that I’m nervous to switch things up,” she says. “It’s like a grown-up playground for my creativity and ideas.” Nathalie’s work brings her into contact with many different stylists, designers and artists, so her home gives her a space to display the eclectic mix of objects and collectibles she’s accumulated through her job. Some of her favorite items include her grandmother’s couch, a hi-fi stereo and the various art pieces she’s collected over the years. “At least 90 percent of my furniture is stuff that I’ve inherited or received as gifts or was made by friends, so I guess my decorating style is pretty sentimental,” Nathalie says. “It means a lot to me to be surrounded by items with history—either because they’ve been passed down through my family or created specially by close acquaintances or because I’ve somehow fallen for the soul of the object.” Nathalie is a firm believer in bucking interior-design trends in favor of staying true to what feels comfortable and organic to the space and the person living in it, and she stresses the importance of personal style and authenticity. “Objects in the home should be a natural extension of the resident’s lifestyle—otherwise they’ll feel strange and out of place,” she says. “It’s kind of like wearing a huge dress when going to play soccer—it just doesn’t function all that well.”

Nathalie’s Frama wall light serves both as a lamp and as a small bedside table. She loves reading in bed and is currently perusing Beyond by Dan Graham. A Rodin sketch and a picture of a mountain she found at a flea market are on the wall.

Nathalie’s wallpaper is by Farrow & Ball, a traditional English paint and wallpaper company.

Top: Nathalie’s vintage table is a type that was once traditionally used in Danish kitchens, and her lamp is also vintage. She enjoys decorating her house with various plants from her local florist.

The artwork on Nathalie’s wall is a print by American painter Mark Rothko and she found her vintage coffee table at a Comme des Garçons pop-up store. Her morning routine involves drinking two large cups of coffee and listening to talk shows on her dad’s old radio from the ’70s.

Since their creative partnership began in 1995, contemporary artists Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset have based their collaborations on breaking down the barriers between public and private spaces. “The conventional notion of what’s considered public and private is a social construct that we’ve inherited from past generations and needs to be constantly reevaluated,” Michael says. When they saw an advertisement for a water pumping station in Berlin’s Neukölln neighborhood 10 years ago, they adopted this concept while developing their own uniquely structured space. For years, the building sat unclaimed on an unassuming residential street adjacent to a small overgrown meadow covering the former reservoir behind it. It had remained empty because no one could imagine how to appropriate such a large space in a non-industrial location—that is, until Michael and Ingar found it. “We were looking for a place that could meet many different needs, such as workshops, office space, archival space, living space and social space,” Michael says. After purchasing the sprawling warehouse-like structure, they renovated and divided the building into a number of different zones to be used for domestic life, work and socializing. “On a typical day here, there can be up to a dozen people working on different projects and eating lunch together in the kitchen,” Ingar says. “We also have a number of guest rooms and some more domestic-looking areas where we have meetings. Flexibility is key.” Although the former couple both lived here for many years, Michael currently splits his time between London and Berlin, and the space now operates primarily as the main studio for their artistic practice under the name Elmgreen & Dragset. Their staff works from various areas in the building and seasonally shifts between the open main floor in the summer and a smaller winter office to keep warm, as a building this large is notoriously difficult to heat. Features such as the main hall’s 42-foot (13-meter) ceiling are used to create full-scale mock-ups for installation pieces, and the front doors swing open so crated artwork can be moved into and out of the studio. Michael and Ingar have filled the rooms with a lot of their furniture from past shows and art projects. These items serve as a constant reminder of the evolution of both their space and their artistic practice. “When we use furniture in our exhibitions, it’s chosen to convey a certain emotion. When it leaves the context of the exhibition space and is used in our home, the functionality usually remains, but the meaning slightly shifts,” Ingar says. “After all, there’s a good portion of ourselves in any of the characters we invent for our projects.”

In the following interview (see here), the artists talk more about their work as Elmgreen & Dragset and the nature of public and private space.

This Henrik Olesen photograph is one of Michael and Ingar’s favorite pieces. The ceramics are initial prototypes of a few of their artworks, and they collaborated with Wenk and Wiese, the architecture firm that renovated their building, to design the fireplace.

Right: These photos are from the 2005 Elmgreen & Dragset project “Deutsche Museen.” They asked a number of German museums to send representational images of their exhibition spaces when empty. Eight images were selected, manipulated and printed as photogravures.

Michael and Ingar’s warehouse space covers nearly 11,000 square feet (1,000 square meters). These bookshelves contain their entire press archive over the past two decades, which includes magazines and publications dating from the mid-’90s to the present.

Elmgreen & Dragset are an artistic duo known for turning gallery spaces into illusions of private homes, complete with dirty dishes left in the sink. They discuss what happens when private homes and public spaces intersect and what it’s taught them about crafting their own living quarters.

What messages about the blurry line between public and private space are you trying to explore through your art? — We’re interested in how the function of public space has changed over the past few decades and how its role has been displaced within our contemporary digitized culture. Many interactions—such as socializing and exchanging opinions—used to take place in public spaces but now take place online. Today politicians and urban planners seem to regard public space as a problem that needs to be solved, rather than recognizing its potential for creating new social platforms. We try to look more deeply into whose stories get to be told and what viewpoints are being presented. In some of our projects, we’ve also explored what kinds of power structures are in place in both public and private spheres and what desire mechanisms guide our behavioral patterns or dictate how we experience public designs and architecture. We’ve also worked with simple structural alterations of spaces in order to show how easy it can be to twist the conventional use of a specific place, whether it’s a museum, a gallery or a public square.

Your home contains many different spaces that are both publicly accessible and private. How have you learned to separate your personal lives from the work you do with your team at home? — We have some communal areas that are accessible to everyone and some areas that are more private, though never completely. Nothing is formally mapped out, and we try not to have any specific rules in the space. There’s a sort of unspoken general understanding between all of us at the studio about where everyone goes and when. For example, the main hall is always open to everyone as it’s also where we produce many of our works, as is the kitchen, which has many different functions and is sort of a central meeting point. The upstairs area is understood to be more private—on a typical day, the studio staff doesn’t go upstairs unless the weekly yoga class is taking place or there’s some special meeting or guests are visiting. It’s the quietest part of the building. We also all have lunch in the garden together in the summer.

When decorating our homes, do you think we should make decisions based purely on our personal preferences or be mindful of what those objects say about us? — You should make decisions based on personal preferences,for sure. We shouldn’t be ashamed of showing our desires, perversions, neurosis or banalities. A home should be a place that reflects your personal taste—an environment that’s crafted by the inhabitant.

The residents in your home-based exhibitions are nearly always absent, leaving us to conclude what types of people they are from their belongings. What do you think the belongings in your own home say about you? — You could say that putting these spaces on display highlights the urgency of having a private sphere—a place where we dare to be ourselves, with all our obsessions and phobias, without being judged or watched. The objects in the studio reflect many things—our weird passions, our inspirations and our cultural backgrounds as Scandinavians. For instance, we’re always reading, and our custom-built bookshelves upstairs hold a wide range of titles that have influenced our work: There are books on gay culture, performance art, philosophy and architecture, as well as theoretical essays on public space, among other things. Most of the artwork you see on our walls is from friends. A lot of the pieces of furniture are relics from previous exhibitions or vintage stuff we’ve bought at markets or in secondhand stores. And a few designs we’ve made ourselves because we couldn’t find what we were looking for.

What has living in a semipublic setting taught you about yourselves? — The studio layout has definitely been instrumental in reshaping our working method, and we’ve learned that this kind of semipublic setting can create new rhythms of productivity and encourage us to cross some borders. It’s been important for both of us to overcome our own shyness and dare to show things that are still in progress—things that might not appear visually optimal yet. Having more public exposure in our private sphere teaches us to be less fearful and less vain.

How do you think our attitudes toward opening up our private spaces to strangers are changing? — Airbnb—along with social-media sites such as Facebook and Instagram—has played a big part in shifting attitudes toward opening up not only our private spaces but also our intimate moments to strangers. It’s becoming quite normal to display more and more parts of our lives online: It’s a new way of profiling yourself for the world and forming a carefully crafted identity.

What’s the relationship between architecture and public art? Should our homes’ exteriors be treated as works of art? — No, too much architecture is already reduced to its exterior—buildings that are only skin with no organs. Public art projects should be more architectural instead; something that could be inhabited would be far more interesting.

The timeworn features of Aurélie Lécuyer and Jean Christophe’s house make their family feel at home. “We love places that have a story, a past—places where materials tell you something special,” Aurélie says. The couple recently bought an apartment in Nantes, a beautiful city in western France, in a building that dates back to the early 1900s. Both inside and out, their home’s environment has the casual energy and ease of a bygone era: Hallways are filled with the sounds of their three children—Gustave, Honoré and Blanche—playing, and everything they need is accessible by foot, from their school to the market and the local cinema. The combination of the area’s storied history and the constant activity in and around their home often reminds Aurélie of the fluidity of domestic life. “I can’t imagine a finished home,” she says. “We think about it all the time, and it can’t be static. A home is permanently evolving, just as children do and as we do. It’s quite impossible to keep something frozen in time here.” As a stylist, Aurélie sees every element of an interior as a contributing factor to the tale being told by a decorator. “Depending on the objects we collect and the conversations they start together, there are so many stories that come to life in a home,” she says. The couple believes the whole structure is a moving organism that reflects its inhabitants’ narratives—as each family member’s passions and personal tastes change, so does their home. “The materials, colors, forms and the added tiny little details tell their own stories. Each creates its own universe,” Aurélie says. She and Jean believe the space you create is meant to foster a sense of relief from external daily pressures. But as everyone’s desires and whims are different—especially with three kids—they think it’s important that each member of the family has a designated private space, a “kind of personal cocoon.” Providing a personal universe for each family member gives everybody the opportunity to relax away from the nonstop hustle of household life. For her own purposes, Aurélie added a separate workspace in the master bedroom. “The apartment isn’t that big, but it’s always quiet there even when it’s not in the rest of the house,” she says. “That’s enough for me—a quiet space and an outside view.” But despite her dedication to finding a personal place within the home, Aurélie still enjoys absorbing inspiration from her family for her work. “Clothes from Blanche’s wardrobe help me set up colors, Honoré’s drawings are placed on my inspiration boards and Gustave’s rigor shows me how to organize myself,” she says.

In the following essay (see here), we consider how children change both the meaning and the function of a home.

Top: Aurélie finds pictures in magazines, frames them and then hangs them up on her children’s walls.

Bottom: The tree wall-paper is by Swedish brand Sandberg.

Aurélie and Jean’s vintage sofa was designed by Michel Ducaroy for Ligne Roset in 1973.

Aurélie discovered these wooden shelves at a vintage store. Her son Gustave loves his collection of toy cars—his grandfather gave him some, and his parents pick up others for him when traveling.

The couple found this cowhide rug at a flea market and the mobile is by the Toronto-based brand Bookhou.

Welcoming children into a home means more than just spaghetti stains on the carpet and plastic dinosaurs scattered on the stairs: Kids can also help us define our homes, teach us what’s truly important and encourage us to let the meaningless nonessentials slide.

Having kids doesn’t just change a home—it revolutionizes it. When children are introduced, the dwelling undergoes a metamorphosis, and each parent needs to find a new way to live and share as they cross the threshold into an otherworldly terrain brimming with a mysterious and intoxicating energy.

When children are added to a home, the change is palpable. Olive forks become tridents for a miniature Viking ship. An uneven heart is etched into the leg of a once-flawless antique end table. Pots and pans are now percussion, sippy cups get stacked with the teacups and the hallway is scribbled pink after a toddler took your “wanting more color in the house” remark literally. You start to find things in unusual places, like the horse figurine inside the empty French press or a raisin smashed onto the piano’s middle C key. Others are inexplicably lost: the strap from your handbag, a Rolling Stones’ Aftermath record, half of the soupspoons. A living room that remains perfectly tidy for more than 30 minutes becomes a faded memory. The balance between order and chaos is delicate, and entropy seems to always be lurking around the corner.

What may seem to be wild cohabitation to the uninitiated onlooker is actually a home that’s evolved past the need for perfection; one that revolves around creative living and growing. Relics of experiences and projects fill every corner: That pile of wooden safari animals symbolizes a dangerous adventure, and the books tossed on the disheveled bed are remnants of a reading party.

Stanford University’s d.school founder David Kelley maintains that when a space is considered an instrument for openness and originality, it becomes “a valuable tool that can help you create deep and meaningful collaborations.” Guided by little minds that are more interested in new ideas than in keeping their feet off the furniture, child-filled houses embody what numerous academic studies and books such as Simplicity Parenting and The Third Teacher have supported: that an intentional environment can liberate individuality and potential. The realities of running a child-filled home confirm there are more important things to do than worry about fastidious order.

Savvy parents all over the world demonstrate the art of filling a home with dynamic childishness while refining its style. They have the ability to skillfully integrate the worlds of children and adults, which is the aesthetic equivalent of calmly cradling a baby in one hand and a cappuccino in the other: Picture books in a Paris apartment mingle with the uniformity of orange Penguin novels; a rope swing hangs over a Tunisian rug in a Brooklyn living room; and concrete halls in a house in Auckland become tricycle runways. It might come at the cost of stains, spills and fiascos, but homes like these have encouraged an intricate pattern of living that wards off potential stagnation.

Homes with children seem to reflect a psychological redesign of the parents that dwell in them more than any shift in style or pattern of living: Where there was once constant order or perhaps a little architectural egocentricity, there is now spontaneity and blissful altruism. The family dwelling might appear primal at times, but nothing is more civilized than humans expanding their capacities and reflecting these evolutions in the ways they live together.

After founding TRUCK furniture nearly two decades ago, Tok and Hiromi Kise dreamed of creating an integrated space that combined their home, workshop and storefront into a single property. Thirteen years later, they made the move to a site in Osaka’s Asahi ward that does all that and more: It accommodates their workshop, the store that sells their furniture, Hiromi’s handmade leather goods shop called Atelier Shirokumasha, Bird Coffee (a café they opened so customers could relax with an espresso while shopping) and the house they live in with their young daughter, Hina. “We’d previously rented an array of separate buildings that were rather spread out from each other, so we wanted to gather them together into one cohesive connected unit,” Tok says. After living in somewhat cramped quarters above their workshop in the Tamatsukuri neighborhood, it was a relief to relocate to an area where their family could live comfortably. Having these spaces in such close proximity allows Tok and Hiromi to transition between them with relative ease several times a day. “I give our cats and dogs breakfast first thing in the morning and then wander out into our beautiful garden to feed the birds,” Tok says. “I spend the rest of my day going back and forth between the store, the workshop and Bird Coffee. I don’t particularly separate work and rest, but it works for me.” As Tok and Hiromi’s busy schedules leave little time for cooking in the middle of the day, they often drop by Bird Coffee for a quick bite to eat and to catch up with each other over lunch. Tok enjoys spending his evenings relaxing with a beer or playing with the family’s pets: Most of their five dogs and eight cats were adopted.“We kept finding newborn kittens just lying on the side of the street and ended up taking most of them in, so thankfully none of us have any allergies,” he says, laughing. Constructing this property was a labor of love that the pair feels was entirely worthwhile: They’ve even published a book titled TRUCK Nest that documented their quest to create a place of their own. “The book is a record of the hard work, dedication and inspiration we put into envisioning this space,” Tok says. “We longed for a space like this, and we made it a reality.”

Right: Tok and Hiromi enjoy relaxing in their outdoor patio area over coffee in the morning or a glass of wine after work.

Tok’s friend and textile designer Akiko Takahashi made these sitting figurines out of clay and fabric. The boots on the left are from the Australian brand Rossi Boots and are Tok’s favorite pair of shoes.

Growing up on the beaches of Santa Monica as a quintessential Southern California girl, Jenni Kayne learned to appreciate the qualities that a lucky and happy life in Los Angeles center around: light, play and comfort. She and her husband, real estate agent Richard Ehrlich, bought their home 10 years ago and made major moves to strip the property of its cold features. “I wanted to build a modern house that was all at once warm and functional,” she says. Their success is reflected in many areas of the home, beginning with the entryway that was remodeled to incorporate large glass windows and high ceilings constructed with reclaimed Amish barn wood. “I really wanted the home to have a flow from the inside out,” Jenni says. “The entry is where this starts.” The expansion of energy from the front to the back of their house creates a sense of openness and lots of light. When the doors are open, there’s a seamless connection between the outdoors and in, both visually and physically. “Anyone who knows me knows I love to entertain,” Jenni says. “So being able to open all the doors to create an open space is one of my favorite parts of our home. I love that my kids are able to run from the backyard right into the kitchen.” Making a comfortable, playful home for their children, Tanner and Ripley, was key for the couple. They began renovating the house when Jenni was pregnant with Tanner six years ago, which allowed them to design with children in mind from the start. “We all hang out in the playroom—it’s an easy, comfortable space,” Jenni says. Practicality and relaxation are clear themes throughout the home, with Jenni describing her decorating style as “clean and minimal, but functional.” Although her self-titled collection has a classic aesthetic, she’s still often surrounded by patterns and colors as part of her daily creative process. She therefore keeps her home’s palette neutral and chooses interesting objects and textures to draw the eye toward subtler details. “No one item jumps out at you, but I love to mix materials,” Jenni says. “I have ceramics from Dora De Larios and Heather Levine, metals from Alma Allen and glass from Caleb Siemon.” Despite their collection of decorative pieces, Jenni says that nothing inside their home is too precious or off-limits to her children, which helps reinforce the relaxed nature that defines both their family life and the home’s atmosphere.

The staircase is one of Jenni’s favorite features of the home. She loves its shape, the curve of the railing and the natural light that floods in from the skylight.

The burlap light fixture is from Tim Clarke’s shop in Santa Monica. The dining table is a Live Edge table from Lawson-Fenning and the chairs are vintage leather and metal pieces from Emmerson Troop.

These cherished sketches are a series of charcoal drawings from the 1960s that belonged to Jenni’s father and have followed her every time she’s moved. The African baskets were a gift from her mother.

Left: Jenni loves collecting ceramics for the earthiness and warmth they bring to a room. Her kitchen shelf contains ceramics by Victoria Morris Pottery, Alma Allen for Heath Ceramics, Humble Ceramics and Irving Place Studio.

Hannah Ferrara and Malcolm Smitley’s home life is rooted in their love of entertaining. The couple moved to Portland, Oregon, from Asheville, North Carolina, in 2013 and made it a priority to find a house that could accommodate frequent gatherings with their family and friends. “Having a dining room large enough to fit a big table and a functioning kitchen spacious enough to prepare meals was key,” says Hannah, the designer behind jewelry line Another Feather. Malcolm is a former chef who relishes using different cooking techniques to create an assortment of dishes for their guests. “Malcolm loves cooking over wood fires, so large meals with friends often include some sort of whole fish, roasted vegetables, a cheese plate and a large salad with fresh figs from our tree outside,” Hannah says. As she and Malcolm both wanted a creative space at home, it was imperative that their house contain a suitable studio area with large windows to let in lots of natural light. They found the ideal spot in their attic workspace, which is outfitted with separate workstations, a central shared table and narrow desks that line the length of the walls. “After spending years with separate work schedules, we especially appreciate the fact that we now have the chance to both live and work together,” Hannah says. They separate their work and home lives by limiting themselves to the studio during most of the workday. This makes them feel more productive and mentally checked-in with their tasks. They also try to set aside at least one full day a week to take their minds off work and spend time outdoors. Hannah and Malcolm chose to balance out their home’s rustic character by introducing modern pieces of furniture and are also discerning about what they surround themselves with. “I’m often visually drawn to so many things and want to bring them all home for inspiration, but I’ve found it hard to create or reflect if there isn’t any blank space for me to think and rest my mind,” she says. “If I do bring things in, I try and get rid of something in exchange.” While Hannah and Malcolm miss their families on the East Coast, their efforts to foster community have helped them adjust to the rhythms of living in the Pacific Northwest. “People can live somewhere their whole lives without truly feeling at home, and then stay somewhere for a week and feel it right away,” she says. “The West Coast is filled with components we didn’t even realize we were lacking until we moved here, and I’m thankful for the chance to experience this definition of home.”

In the following essay (see here), we explore how entertaining at home can bring warmth to both your community and your kitchen.

Top: Hannah and Malcolm’s coffee table is by Muuto and her favorite item in the room is a self-watering ceramic planter by Light + Ladder, which is great for keeping their ficus tree alive when they’re traveling.

The couple loves hosting big brunches. The spread often served up at their gatherings includes pancakes, baked grapefruits, frittatas and fresh juice—as well as eggs Benedict, if they’re feeling fancy.

Hannah keeps a linen pinboard in her studio with a rotating collection of clippings, images, textures and objects that help inspire her creative direction. Shapes, architecture and the human form also influence her work.

Hannah and Malcolm love the soft light and slanted walls of their attic studio.

Once viewed as a time-consuming and showy affair, modern home entertaining has now taken a more casual approach. By shifting our focus away from the superficial details, we can concentrate on the most important aspects of the meal: the people gathered around the table.

In a bygone time, home entertaining wasn’t for the faint of heart. Having company once necessitated matching china, polished cutlery and plenty of chairs to go around. Messes were hidden from view and decadent roasts came out of massive French ovens—steaming, juicy and perfectly laden with lemon and thyme. For some, the thought of throwing a soiree can be daunting, partly because of the Downton Abbey–esque expectations that come with having a memorable dinner party.

Thankfully, our perspectives on hospitality have shifted from this archaic vision, and the idea of gathering together now means something more than just facilitating a grand performance. Inviting both friends and strangers into our homes has become an intimate act that welcomes participation—not only in the communal preparation of food but also in the messiness of daily life. (Truly, who has time to wipe down dusty baseboards or clean the expired jars out of the fridge?)

This more casual approach to hospitality no longer requires the host to forego days of eating just to finance the purchase of enough lobster tails to go around. And for those who subsist mostly on cereal for dinner, there’s still hope for throwing a wildly successful fete without people going home hungry. No matter where your skills lie on the kitchen spectrum, there are myriad solutions for filling your house with friends (and filling their bellies, too).

The joy of gathering is found in the act of simply being together instead of the theater of putting on a good show. It doesn’t matter whether meals are shared at a proper table, balanced on laps while sitting on the front porch or eaten while reclining in the middle of your studio—unconventional settings can leave us with more intriguing memories. Likewise, for those less adept at cooking, there’s no shame in picking up pizza, sushi platters or Thai takeout, or asking pals to combine forces for a potluck.

Regardless of what’s on the menu, the most important gesture is simply taking the initiative to gather folks together in the same place and time. Relationships deepen when we transcend the safe zone of meeting friends at restaurants, bars or the park. We invite them into the particulars and peculiarities of our homes, which are often mirrors of ourselves. The home compels a more candid exchange than other settings, if only because the frame with our mother’s likeness in it or the heirloom on the mantel prompts a dialogue that otherwise would have never taken place.

By shifting our attitudes about the true motivation for dining together from grandeur to gathering, we can overcome our hosting fears to find that entertaining is an easily gained source of joy rather than a cumbersome task. It doesn’t matter what you’re eating or how the dishes are being served: There’s no better way to spend your time, foster community and share your true self with the people you know and love than welcoming them (and their trays of treats) into your own comfortable abode.