Map Your Natural Style

You’re coming to this book with established productivity methods—at the very least, the ad hoc system you’ve developed from your work habits. In many cases, these came with their own presumptions about what productivity means: how you implement it, how you measure it, and how you judge yourself in relation to it. I’m going to refer to all that as your natural style.

“Natural” in this case isn’t something you were born with, or even a necessarily positive attribute. What comes naturally to you is a function of what you find comfortable, which for many people means “the methods I learned in high school.” The results of what’s “natural” to you are what led you to be interested in improving your productivity, so clearly those methods fall short in some ways. Comfort is an important attribute, though; you shouldn’t always sacrifice it in favor of improved productivity, but instead should balance the quality of life that comfort provides you with the productivity you gain from temporary discomfort.

Considering your current approach is the first step toward adopting a new system. You’ll use this information to make better decisions (starting when you Choose Your Tools).

Elements of (Natural) Style

With apologies to Strunk and White for the heading above, here are the topographical features of the map of your natural style. Note when they already apply to how you think of your actions and destinations.

Roles, Goals, and Journeys

Nearly everything we do has an unstated why behind doing it; it could be anything from “this task will make me money” to “completing this project is part of my purpose in life.” At the same time, some things you do aren’t projects that you can finish, but instead stem from long-term and lifetime responsibilities. Clarifying both of these helps you state your plans in terms that reflect their true importance to you.

Roles

A role is something that doesn’t change unless your life changes radically. If you have kids, you have a role as a parent; that role expresses itself differently at the various ages of your children, but the basic role doesn’t change, and it never goes away.

You may frequently see your roles as being in the category of “so blindingly obvious, I don’t think I need to plan it.” That’s fine if you’re completely satisfied with how you’re fulfilling that role—but by planning it, you can make explicit choices about how other things move around to accommodate their corresponding importance.

Alternatively, you may want to plan a role in order to demonstrate for yourself how well you’re fulfilling it—quantifying the unquantifiable, as it were. You can’t create a task to “be a better parent,” and you probably shouldn’t make one to “spend quality time with my kids 30 times this year,” but you can certainly have one to “make time for my kids,” then implement that in ways that work for both them and you. (Most children don’t respond well to “not now, Daddy doesn’t have quality time scheduled until 4 p.m. Thursday.”)

Goals

A goal can be as large and important as a role, but it has a defined completion. At the smaller end of the scale, goals are functionally identical to big projects or New Year’s resolutions; at the larger end, they comprise the “bucket list” of things to do before we die.

Goals should be planned, because if you’ve set a goal for yourself but it’s not expressed in your planning, you’re leaving its accomplishment up to chance and memory. Likewise, it’s important for you to be concrete in stating what you plan as your goals. You can’t decide to be more financially well-off; all you can do is decide to make more money, spend less, and save more. But none of those three is suitably concrete, either. For example, “spending less money” is typically a result of other decisions you make and actions you take; you can decide to eat out less frequently to spend less, but the action isn’t spending less, it’s deciding to cook at home.

As you adjust to these new habits, you can judge both whether a particular action you took resulted in progress toward the goal and whether the emotional cost of that action was worth the goal. If eating at home reduced the quality of your life by stressing you out from all the cooking and cleaning, you’re not beholden to that method of reaching that goal, or even to the goal itself.

Also, you’ll want to determine when to state a goal as a specific one you can definitively achieve at some point, versus something more open. “Save more money” is something you’ll never complete; there will always be more to save. The more specific goal to “save $10,000 this year” could be a way of feeling accomplishment, but on the other hand it could be an entirely unrealistic number that only serves to make you feel bad.

Journeys

I’m using journey to describe anything you do for the enjoyment of doing it, regardless of what results from it. Most amateur musicians have no plans of going to Juilliard and no set goals beyond “don’t embarrass myself if I perform,” but they practice because they enjoy the process and the feeling of becoming better at it.

In a few cases, journeys take on the mantle of roles, but unlike roles they usually ebb and flow depending on whatever else is going on. The purpose in identifying journeys is to make sure they don’t ebb to zero. If you entirely cut out something that fulfills you, it’s no wonder that you’ll end up feeling less fulfilled. Plan your journeys in order to make time for them.

Outcomes vs. Benefits

Goals are tricky to define when we phrase them in terms of a desired outcome but our actual interest is in the benefit they provide. Consider a goal of being exemplary at your job: if you’re invested in the work you do, that in and of itself may be your goal. But if being exemplary is an intermediate step leading to a promotion you want, you’ll instead set several concrete goals toward that end. (You can’t have a goal of “get a promotion” because that’s beyond your control, and your goals should be phrased in terms of what you can do.) That said, if you achieve those concrete goals but get passed over for the promotion anyway, you should both give yourself credit for doing what you set out to do and make decisions about how to change your future actions (or your job) such that you get the rewards you want.

This can get ridiculously confusing when it comes to money. Nearly everyone works because they have to (or perceive they do), with most of us doing things that we wouldn’t do for free in a hypothetical Star Trek moneyless economy. No matter how much money you have, more is always better, but studies reliably show there’s a limit to how that translates to happiness: the correlation of wealth to happiness is a classic reverse hockey stick, a steep rise followed by a plateau. Money greatly improves the happiness of people who didn’t previously cover the basics of Maslow’s Needs Hierarchy, but after that people enjoy smaller emotional improvements until they reach comfortable middle class. The relationship between income and well-being drops off a cliff with further wealth accumulation. It’s fine to want to increase your income or savings to solve specific problems, but you shouldn’t expect “more money will make me happier” unless your current income is well below average (which, please note, doesn’t mean the average of the people you consider to be your peers).

When planning, be as clear as possible about whether a goal is a particular outcome or a benefit related to that outcome. In the latter case, there may be a disconnect beyond your control, so perhaps have a Plan B should you not get that benefit despite accomplishing your goal. You may come up with better ways of reaching the same benefit. Minimum-wage workers may try to increase their income by working overtime (which is a goal beyond their control), but in nearly all cases their better option is to find a higher-paying circumstance and do what they can to get there, if possible.

Approaches to Planning

Your system builds upon several big-picture decisions you make about how to plan your time and productivity—decisions so large that most people are unaware they’ve made them. This is particularly the case for people who rely on the productivity strategies they learned as teenagers, with only minor modifications since; those strategies were likely one-size-fits-all, and may have never worked for you. They have no correlation to who you are when you’re no longer in school, or after years of work experience.

Trusting Your Brain vs. Writing It Down

Most people, most often, trust their brains to keep everything straight. It’s the unstated method of people who dash off a daily to do list every morning; you may refer to the list during the day, but you’re trusting your brain every morning to consider what’s on deck, and to come up with a reasonable list of the daily tasks that are highest priority.

Few people should use that method, simply because brains aren’t very good at it. By definition, what arrives on that daily list is whatever is on your mind. Important things that don’t catch your attention get missed—such as journeys and goals without deadlines attached, or important outcomes that are self-driven with no external oversight. Planning important things by writing them down in advance is better because once they’re written down (and you refer back to your list), they’re unlikely to automatically play second fiddle to lesser tasks.

However, writing everything down does come with some costs:

On the plus side, writing something down means you can allow yourself to forget it almost immediately. You won’t have to worry if you’ve addressed everything that hit your radar over the course of the day; it’s stored somewhere, and your mind is clear.

On the other hand, relying on notes and lists works only when they contain everything. If you write down nine things and trust yourself to remember the tenth, you must also remember that you neglected to record the tenth thing. That’s two things you’re remembering.

Writing everything down takes time, and can break your chain of thought. A good idea, or a new task from someone else, can arrive when you’re in the zone on something else; you have to be able to get it down somewhere, and off your mind, so quickly that it doesn’t distract you.

Writing everything down feels silly until you get into the habit. You think there are things that you “should” naturally remember. If you actually do remember, and follow through, that’s great. But why not write it down anyway, to rule out the possibility of forgetting?

I lean in favor of making a blanket recommendation to write everything down. However, there are some people who are excellent at holding things in their brain. Give the write-it-down strategy a try regardless. It may lead to some lost time because you’re planning out things that don’t need to be planned—but in that case you can drop it if it’s not useful. You won’t know if it’s a helpful strategy until you test it.

Freestyle vs. Structured

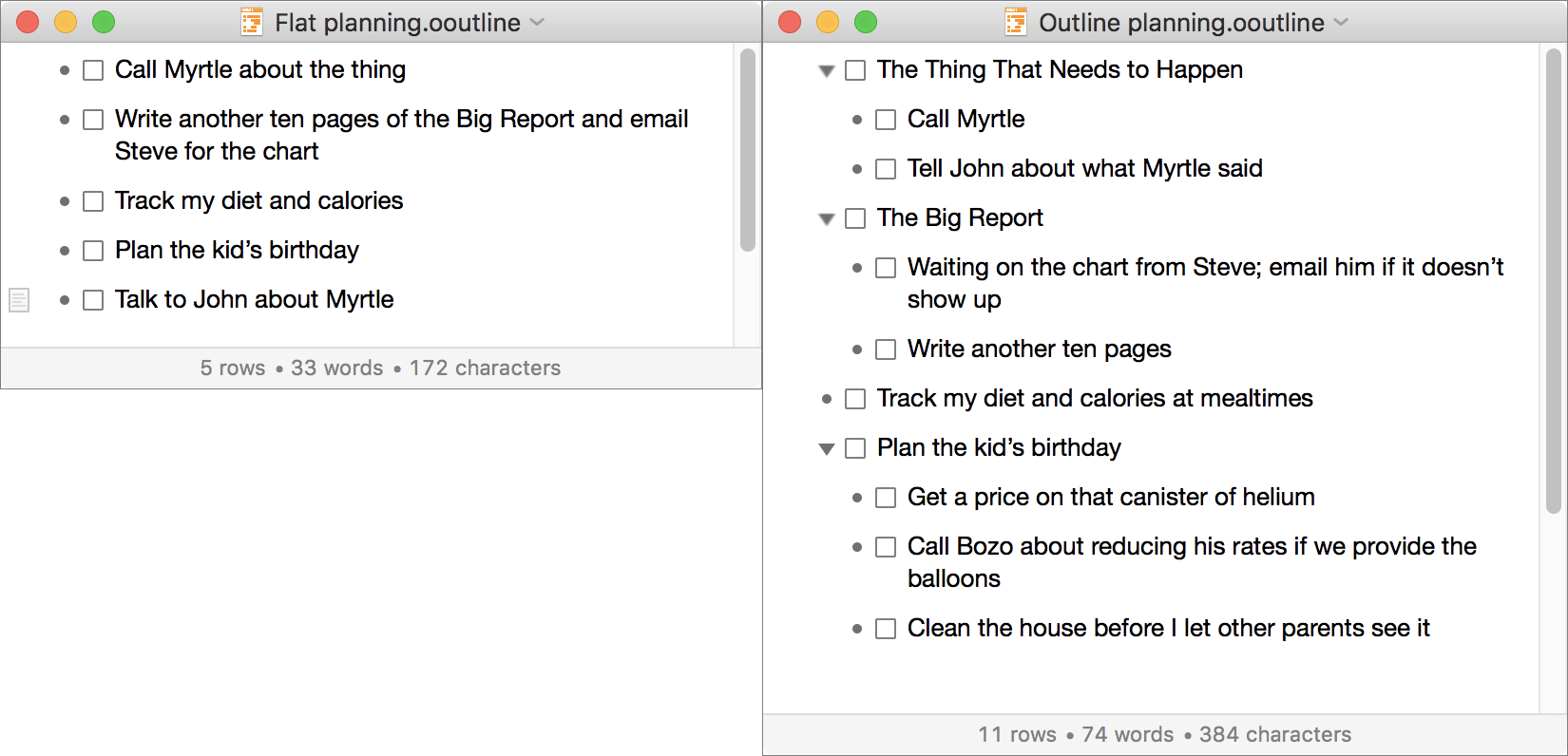

Consider the two methods of planning your day shown in Figure 2.

The list on the left is flat—one item listed after the other, without any hierarchy showing subtasks. On the right is a nested list: either a heading task has subtasks beneath it or items are grouped together in some kind of logical way.

The flat method is how most people brainstorm lists. Note that this method results in a flat list with a mix of simple tasks, small projects, and vague goals, and most are missing details that are more usefully included in the nested outline. “Plan the kid’s birthday” is, as shown on the right, several different tasks that happen in a particular order. Calling Myrtle is a one-off task, but in the nested list, it groups the context of why you’re calling her.

Flat lists have a decided speed advantage, but nested lists allow for deeper planning and bigger projects. Most people have projects complex enough to require nested lists; flat lists are too simple. My recommendation is nested lists usually, flat lists when sufficient.

Work-Life: Separate or Combined?

It used to be, a few decades ago, that work and the rest of life were comfortably split. You went to the office, and you worked there; you went home, and you turned off work mode. Then we invented things like iPhones and Wi-Fi, email became a 24/7 kind of deal, and many people are effectively “at work” whenever and wherever their laptop is powered up.

Self-employed people, and everyone who’s now in what we’re calling the “gig economy,” are even more likely to mix the two. If 2 p.m. is the best time to see a movie, and 2 a.m. is the best time to complete a project, no problem. Sometimes the ability to do this an advantage; other times, work becomes a monster that eats everything else.

For a decade or two, we’ve called this “work-life balance,” and it’s taken as axiomatic that well-adjusted people get to “have it all.” If one side suffers due to the other, you must be doing something wrong—especially if you’re a woman. But that’s obviously poppycock.

We all know that when work gets rough, we’re going to cancel events in our “life” to make more time. Conversely, most people agree that a job that doesn’t accommodate when you or a family member are seriously ill is a bad job. But we have a blind spot for jobs that routinely take the place of most non-work activities, so long as they pay well or come with other perks. They’re seen as “good jobs that require a lot of you” (not “bad” jobs)—but that’s true only for people who don’t place much importance on what they’re sacrificing. For everyone else, they’re bad jobs, just cushioned with money.

There’s another way you have to figure out how to approach the question of work-life balance: you must decide whether you’re managing only your work or the whole kit and caboodle. I personally don’t understand it, but for some reason people tend to gravitate to organizing only what they define as their work. When it comes time to think about what frustrates them, though, their “life” is the source of most of it. (People are frustrated about money and not having enough of it, but that’s not work—that’s the benefits of work.) You’ve often heard that no one on their deathbed says, “I wish I’d spent less time with my family.” To that I’ll add that few people who didn’t own their own business, or didn’t view their job as a calling, will say they wish they’d accomplished more work goals. More frequently, what they most regret are the benefits they didn’t get.

That said, doing your work well is obviously important, for a bunch of reasons. But it’s of varying importance depending on what else is going on; until you have some way of measuring those big-picture priorities, they’re going to be set by default—usually in favor of work, and usually without compensating you for its privileged status.

For now, decide which of the following approaches better suits your style and preferences:

Manage everything: If it takes time, it should be managed. Otherwise, your preferred leisure activities, and other things you regularly rob time from, won’t get suitable attention.

Manage work and big projects: Day-to-day life stuff can go with the flow; it’s too much effort to try to impose order on it. You manage only your work and those select few other things that are big enough to require planning.

Manage work only: Manage your work and nothing else. The whole point of your free time is that it’s “free”; trying to manage it like a project is crazy-making.

I’m inclined to suggest that “Manage Everything” is the proper approach for self-employed and gig economy workers, for ambitious people who see 70-hour workweeks as a light schedule, and for people who thrive in a self-imposed structure (or who know from painful experience that they require one).

Everyone else should do what comes naturally, with one caveat: anything that you’d regret not doing, or that causes friction between your structured and unstructured time, should be planned. If Facebook takes up two hours of your workday, or a Netflix binge causes a night of only three hours sleep, you should manage it in order to control it—and likewise if you’re three years behind on the shows you want to watch, or your friends notice that you haven’t posted on Facebook in a month and wonder if you’re dead.

Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up

Deciding whether to plan from the top down or the bottom up involves implementing some of the observations you made about yourself when you considered your roles and goals.

Some people work well with big goals and then drilling down, as in “be fluent in Italian in five years” and then kicking it off with a project to “complete the beginner audio coursework in the next six months.” Roles can also fall into this category when they naturally lead to large goals, such as the parent planning to build a three-story treehouse, or the community volunteer expanding a Meals on Wheels program to a new neighborhood.

The alternative is to start small, and group things together only when it makes sense to do so. You don’t “spend quality time with your children” over the course of a year, you “read with your kids” three times a week. You might want to take the kids to Disney World someday, which takes time, money, and planning, but it’s not a goal per se; it happens when it happens. It adds up to “be a good parent,” without ever necessarily writing that down.

There’s no right answer; there’s only what works for you. But keep in mind that sometimes the other way will be better. If you’re in the habit of setting large goals and falling short (because you underestimate how long they’ll take, or how much time you’ll have), try the same thing again but bottom-up, which is more likely to start with something you can chew in one bite. On the other hand, if “take the kids to Disney World someday” has the unstated clause “before the oldest turns 13,” more top-down planning is in order to make sure the trip happens in time.

Commitments, Somedays, and Maybes

Some people prefer to restrict their lists to actual commitments: if it’s written down, that means they’re going to do it, by jingo. Others have lists of a thousand things they only might want to do someday. (I’ve spent 30 years saying I’d like to learn how to play klezmer. If anything, I’m further away now, because 30 years ago I was better at the clarinet.) And just about everyone has things they would already be doing if a genie granted them 208 hours in every week.

Your system can handle all of the above, but you should have high conceptual walls between them. If you put too much commitment chocolate into your maybe peanut butter, then instead of being an inspiring list of dreams, your maybe list chides you for how much of it you’re not doing. In the reverse direction, the optional status of “maybe” will wreak havoc if it’s let loose on your commitments.

“Someday/Maybe” is a common term for a maybe list, but these are also two things that should not be mixed. Counting commitments, there are actually three separate categories:

Most places in your system are for commitments: projects or tasks that are not optional when their time comes. Projects may be waiting for a future start date, or on hold indefinitely, but any that are currently active are a commitment.

Some places are for maybe projects and tasks: ideas that were good enough to keep, and perhaps aspirational to consider, but maybe not to do.

Someday places are in between. A Someday project is something you have committed to doing, when you have the time. It’s not on hold (which implies that it was active for a while, but then stopped); it’s a never-started. When you finish a few active projects and consider what else you might want to start, your Someday list is a menu to choose from.

Someday and maybe places are entirely optional, for when you want to keep your ideas for future reference. Distinguishing between them and your actual commitments is not.

At this point, you should have a handle on your top-level life choices that drive the things you do, as well as various methods picked out for how you’ll naturally break those things down into projects and day-to-day tasks. Next we’ll review necessary concepts for good planning—both new terms and new wrinkles on ones you already know.