Fail Successfully

If there’s one thing that’s frustrated me from reading dozens of productivity books over the last two decades, it’s that no one told me how to fail.

Failure is common when you start a new system. What I’ve written is the first time I’ve seen a framework for transitioning from old to new, and the reason it’s here is because it’s a common time to fail. But it can also happen anytime afterward. Maybe your system has become much less efficient. Or something specific derailed you, and you’ve stopped reviewing it, referring to it, and updating it. I’ve read platitudes for how to deal with that, but never techniques.

The corollary is that nearly every productivity author has presented himself as the Platonic ideal of hitting deadlines and mastering New Year’s resolutions. I don’t know about you, but the message I took away from such writing was, “Well, it worked for him, but I guess I’m just not good enough, or somehow negatively exceptional.”

I’m not going to do that to you. The advice I’ve given here, more often than not, regards techniques I’ve learned precisely from repeated failures, and often switching my system wholesale. Meanwhile, writing this book was its own derailing event for me. It’s a huge task, parts of it took longer than expected for reasons beyond my control (although they were mostly my fault), and as a result I regularly blew off my system far more than is my usual.

It’s almost inevitable. At some point, you’re going to go off the rails. Accept it now, and you won’t castigate yourself for it later. Come here and let this chapter point you back to smooth running. (Give it a read now, too. Can’t hurt to be prepared.)

Recognize Your Major Triggers

Earlier, we discussed why you should Have Triggers that draw your attention to specific problems. The ones I’m discussing here are big kahuna triggers; minor triggers tell you when to make tweaks and alter small habits, but these major ones tell you something larger has gone wrong, and you’re not going to fix it with tinkering around the edges. Some possibilities:

A huge project landed on your desk, and it’s made a pile of behaviors that used to work great for you less than ideal.

You realize that you’re working off a legal pad, and you haven’t launched your task app for two weeks.

Someone important to you calls you on the carpet and tells you how they perceive you’re screwing up.

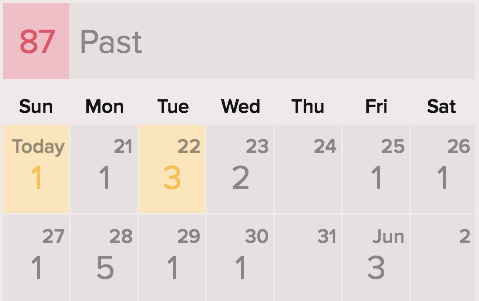

Your Past Due list looks like Figure 19 (in which the red 87 represents your Past Due list) and you’re pretty sure everything you didn’t get to was a hard deadline.

It’s up to you to decide what’s a minor trigger that indicates the need for a new practice or habit, and what’s a major one that tells you to take a more holistic approach. I find the easiest one is, “are you miserable?” The more emotional impact this is having, the less rational you’ve been about adjusting to it (unless you are very good). Emotions are, if you will, a trigger that informs you about your triggers.

When you hit a major trigger, here’s what to do first:

If it’s your first time here, start a new list of notes. No tasks here, it’s pure documentation. Write down how you’re feeling, what’s changed for the worse, and if you can identify them, the downward steps that you took from “doing well” to here. Put these notes somewhere that you’ll never lose them; your task app is a good place.

If this has happened before: breathe. You have experience with this. That might make it easier this time. Take out the notes you made last time, and read them to see if they remind you of anything you can do to make it easier this round. Then start a new set of notes for this time, and put them where future-you will your entire history here.

It is entirely possible that you found this to be emotionally taxing. If so, take a break. Seriously. It could be an hour, or it could be a week. Come back with a clear head. You have official permission to take care of yourself before you get organized. (You shouldn’t need it. Most people do anyway.)

Identify Your Situation

When I finish this book, my professional life will go back to normal. But when each of my parents died, that was a chronic situation that lasted months the first time, and years the second. If a derailing event or change involves your own health, or a something else major such as becoming a new parent, it could be permanent.

It could also be entirely internal. Something changed about who you are, maybe in a profound way, and this is the first time you’ve noticed.

Note what changed. It might even be what’s going to change; many expectant parents are not exactly of sound mind before the birth.

If the situation is temporary, you have the option of limping along until your life resumes as it was. All you have to do is decide whether major changes in approach will improve your mood and abilities in the interim. Usually, it’s worth the effort; the more you “just can’t even” with your situation, the more valuable such changes may be.

If you’re not sure, read through the rest of this chapter, roll the ideas around in your head, and do what you think will work best.

If it’s permanent, you’re foolish if you act as if it were otherwise. You designed your system for a life you’re no longer living. Of course it’s inadequate now. It needs revision, and the sooner you can do that, the better.

If it’s the kind of crisis where you have no idea how it’s going to go: not a bad idea to take your best guess, and also have a few strategies at the start for what changes you might make if it turns out to be longer than expected. The moment you learn it’s worse than you thought will be emotionally difficult. Having your checklist ready—and nice, distracting tasks on it to make you think about something else—is a gift to that future-you.

Keep Your Priorities Straight

Something happened to get you here. It might be a crisis. It’s likely the most important thing on your plate, otherwise it wouldn’t have had the emotional heft necessary to change so many of your good habits.

That comes first. Reorganizing comes second, except insofar as it helps you deal with it. Everything else is third.

You’re about to make another transition similar to (but maybe smaller than) when you first adopted your system. Like last time, this will be somewhat disruptive. When you can’t deal with that, put it off—unless being back on track is now required of you to meet your new responsibilities. If you’re feeling similarly to how you felt when you first adopted your new system, when being disorganized by itself was distressing, getting organized again should come earlier on your agenda.

There are some crises in which it’s socially acceptable to fall apart a bit. Only the worst bosses expect the same job performance from someone who’s lost a loved one. Only the best understand that losing a pet can feel the same way. When others may attribute the crisis to a choice you’ve made—“laziness” due to ADHD comes to mind—people tend to give you less slack.

There is one major exception to this overall approach, and that’s when you’ve taken someone else’s crisis and made it your own. As with so many other things, this is something you can decide to do. But if it’s causing this much disruption, whomever may have decided for you has now lost permission.

For example: someone quit at work, and you started working the equivalent of two jobs to prevent the company from collapsing. That’s great if it’s your choice. But if you don’t own the company, and you’re collapsing, the prioritization problem is where you put yourself on the totem pole. The default should be “you first.”

Anyone or anything that takes precedence: you put them there, no one else may.

Start Over

As you might suspect, the next step is to Get Started with Your Task App again, with a few modifications for crisis management. You’re again transitioning from one system to another. But instead of old and new, you’re transitioning from whatever it is you’ve been doing from the moment you stopped using your system well. The system you’re transitioning to is probably the same one you just left—this isn’t a good time to make huge changes—but it may need some beveling of its edges to accommodate your new situation.

Alternatively, maybe you’re using all the same tools and methods that worked fine for you before, but it’s producing bad outcomes. That’s a more subtle transition. You’re not going from one to another, you’re figuring out what broke, and the series of changes and Band-Aids that make it better.

The steps you took when getting started should work for you now, but for different reasons. Then, those steps worked because they taught you a new way of approaching your organization. Now, they work because they draw your attention to the specific ways things went off the rails, the old strategies that stopped working, and the new habits you implemented unconsciously that didn’t help. (You may also have some new good habits. Identify them and keep them. Make noticing them recurring tasks, if you need regular encouragement: “Did you take a walk around the block this afternoon?”)

Getting Started has modifications when it’s a reboot. What you do differently this time:

Some Get Started steps will be superfluous now, but don’t simply assume they are. They can draw your focus in necessary ways. Give each some consideration before you move on.

Few people should swap out their tools right now, unless there’s a blisteringly obvious reason to add a new one. Lean toward putting up with more annoyances, and away from changes that may cause more disruption. (Faster phone, good. Replacing the software you know with something you’ve never touched before, bad.)

Your original transition was geared toward what was then normal. This is your new one, for now at least. It could change everything from the timing of your daily habits to your overarching life goals. Even if you’re staying in the same tools, anything that already lives there needs some consideration, and that’s next.

Declare “Project Bankruptcy”

There’s a concept called “email bankruptcy.” It’s when someone decides that they’ll never get to the 20,000 messages in their inbox, so they hit “select all” and “archive” or “delete.” Sometimes people send out a blast email when they do this, informing everyone that if they’re still expecting something, they should email again.

“Project Bankruptcy” isn’t quite as drastic, but it’s a useful tool. Everything that lived in your system before, pertained to your life pre-derailment. Some of it’s relevant, some of it is now relatively less important, and some of it has died of neglect. You have to pass them all through a cheesecloth before they get to live in your revised system, because something about them in aggregate caused you to stop addressing them properly when your situation changed.

I can’t tell you how to decide what’s still important, but I can provide the mechanical steps:

All the projects and tasks you used to have? Put them in one big folder, then put that entire folder “on hold” in your task app. This shuts off all their notifications and deactivates every task. None of them deserve your attention or time until you’ve decided individually which ones still do.

If your software doesn’t allow for one big folder, you can archive your archive everything your task app contains, and start with a fresh database. Two things first before you do this:

Check your software’s help to see how it deals with this kind of archiving. Your old data must be readily available so you can use it as a reference when you put some of it back. Some software makes this a true pain in the neck, which is why the first thing I suggested was one big folder in the existing database; if you do it that way, you’re using your existing skills when you move things around. An archival reference is new to you, and will be different to work with.

Keep your existing structure, as that remains relevant. You want your carefully curated contexts that used to fit you like a glove, as some still will. If you have folders you use to organize batches of projects, those are likely still useful. Think of it this way: you’re throwing all your furniture in the yard to decide what you want to keep. You’re not building a new house.

During the first Get Started, you gave early special attention to everything urgent in your old system. This time, you give that attention to your crisis or situation first. Addressing that is prerequisite to literally everything else.

After that’s in your tabula rasa task app, do the same as before: an urgency scan of your old projects and tasks, followed by recurring tasks and sprints to process everything into your new one. This time, it will be easier, as everything you’re considering will be reasonably fresh or obviously moldy. You were more organized before you got off track. That will make this time much faster.

However, there’s a radical difference in the approach you take, depending on whether your new normal is likely temporary, or likely permanent:

Temporary: The major roles, life goals, and other Big Decisions that guided your old system probably haven’t changed in their importance, only in how they should be expressed at the project and task level. Your filter should therefore be bottom-up, as discussed earlier in Top-Down vs. Bottom-Up. You’re mostly concerned about paring down time requirements, and extending out old deadlines far enough into the future so it’s realistic you’ll meet the new ones.

Permanent: You’re never going to have your old normal back. Maybe some of your roles and goals have a permanence of their own, but all the ways you expressed them were in the context of your old normal. As painful as it may be, some of your old-normal Big Decisions may no longer apply. Your filter is top-down.

Not Sure: One of the above options will be less painful if you turn out to be wrong. Do that one. Usually, switching from permanent planning to temporary is a happy circumstance, which lets you pick up things you thought lost forever. Switching from temporary to permanent, on the other hand, can be a gut punch for each thing you were hoping wasn’t lost yet.

When applying this filter, bonus points to anything you enjoy doing, or that recharges your batteries. Major points off to anything that taxes you. You may need exceptional strength to deal with your situation. Be exceptionally kind to yourself.

Don’t skip the management tasks you set up the last time: you still need pointers to check your collection points, review alerts, and everything else you once used to keep it all humming. But if any of these seem irrelevant or unrealistic now, give them a trial run, and dump them if they’re part of what stopped working.

Re-adopting your system is going to change some habits you built when you were derailed; that’s uncomfortable, but completely expected. But definitely note excessive friction or resistance to using what you just rebuilt. That implies that something that broke your old system may have been accidentally added to your tabula rasa one.

When faced with crisis, we seek routine. When confronted with enormous change, we attempt to minimize it. When you resumed planning, you may have been thinking too much about your old normal, and didn’t change enough for the new one. Do what it takes to make the rebuilt system comfortable first. After that, you can shoot for more productive.

Reviewing your formerly active projects to see what should be included now may be difficult. If you seriously diverged from your one-time plans, or if it’s been a long while since you were last here, you’re going to see many things that went fallow. It can feel like a personal roadmap of recent failures. Give yourself a moment to accept that. Then compare it to your notes from earlier, and say, “This is why that happened. It was situational. It doesn’t have to stay this way.”

The easier part: all those things that expired? They’re done. Mark them completed or dropped, and all the things they required you to do are gone. A potentially substantial chunk of your time and effort has just been freed up for other things.

Keep More Notes

As you get back into the swing of using your system again, you’ll also be mapping out the parameters of your new normal. Right now—when you’re getting restarted, and you’ve just taken the initial steps after noting you were derailed—you may think you know what’s coming up next for you. But that’s the thing about the “new” in “new normal.” One way or another, you’re proceeding into uncharted territory.

You’ve dropped what’s no longer relevant, and you’ve added your best guess about how to manage. But it’s only a guess. It’s less likely to be accurate than anything you might have experimentally added to your system in what you used to call normal times. But you can’t guess any better than that.

The way to deal with this: take more notes. Write down everything that might be relevant. Keep more narratives. Document your tasks more thoroughly. Start a diary. Pay close attention to what’s changed about you, your habits, and your emotional cues.

There are a few reasons you’re doing this:

Much of what I’m telling you to write will live in your head in a vague way, until the moment you set them into words. Writing it down is telling yourself what you think. You may write something and realize, “No. That’s wrong. That’s what I’m supposed to think, not what I do think.”

You need new strategies, habits, and approaches to inform the specific changes you’re making to your system to accommodate your new normal. Turning vague thoughts into words, and having them in a reviewable format, is the best way to also get you thinking in those terms.

People derail all the time. It happens to all of us, and it happens more than once. You’re also writing this documentation for future-you, and it will make your life easier when you’re that person.

Review and Generalize

When you get back into the habit of doing regular reviews, you also review all the documentation you’ve generated while failing successfully. Keep the time you spend here brief enough so it doesn’t delay or derail your review, but when you can make the time, inspect it closely.

What you’re looking for is evidence and data points to tell you what’s working. You may notice a marked improvement in your mood between a few weeks ago and now. Your writing could be better, less disjointed, more focused, or more descriptive. (In my case, when I’m dealing with an emotional crisis: fewer profanities and less anger.) Try to draw correlations between what you did, and what noticeably improved. It likely was not noticeable at the moment it happened, but maybe it’s clear now.

Then extrapolate from those specifics to a general category they might reside in. On the day you sat outside in the sunshine, your evening notes were far sunnier as well. Perhaps you need to get outside more? Or maybe the key thing for you was that you took an hour and stopped worrying in a way that you haven’t in weeks.

Once you have generalizations, try out a few more reminders in those areas. Take good notes here as well. This time, you’re figuring out what works for you. If you’re ever back here in the future, you’ll know at the beginning how you took care of yourself now, and will have known behaviors you can resume to improve that situation.

Transition to Normal

In a temporary situation, some of the above steps are highly abbreviated. You won’t have spent nearly as much time, effort, or brainpower making changes. But you will have made some, and when your temporary situation is over, you should review them to see if they should be dropped as no longer necessary. Some of them will be situational, and now obsolete. But for anything you discovered that made your life better (or just made difficult things bearable), maybe you adapt them to better times and keep them.

For longer-term issues, you’re not transitioning back to your old normal, you’re acclimating yourself as best as you can to your new one. But you may still have approaches and behaviors that were suited only to crisis onset, or to defining your new ongoing methods. These can be dropped once you’re feeling… well, if not as in control as you once did, at least as close to that as you think is possible.

Frequently, people respond to adversity by just getting used to it. It’s unconscious, and hence can lead to new dysfunction. You’re going to do it with deliberation, and as a result, with far better outcomes.

Reward Yourself

No, really. Look at what you accomplished: You took a crisis and made it manageable. You were more on top of it than your default would have been, in the absence of this effort and attention. You took care of yourself.

Most important, you made it through. If it’s not over, it’s now normal. No matter what, you are better prepared than 95% of humanity for the next crisis, because you so thoroughly understand how you acted and felt during your last one.

That is a huge accomplishment. Give yourself full credit, then take a break, make space, and do something you enjoy. Make it the most important thing you do for a while. Let it be as memorable a year from now as your crisis will be.