The world seemed divided into two parts – those places where Jews could not live and those where they could not enter.

CHAIM WEIZMANN

1

On 19 November 1942 Hitler was once again at the Berghof. The first snows of the year had fallen and – as ever – cast a blanket of peace over the enchanted Alpine landscape. From the terrace the eye was seized by the crystalline masses of the Watzmann and the Untersberg – where Barbarossa still dozed. In the valley the dusk came early, and from Obersalzberg the lights of Berchtesgaden glittered warmly below. There was no blackout here, and from the night sky the constellations of Orion, Sagittarius and Cassiopeia shone down on the narrow valley.

Yet the recent weeks had been disturbing for the Führer. Indeed the whole tenor of the war had changed since his precipitate decision to invade the eastern Alps, those of Yugoslavia, twenty months earlier in April 1941. Operation Barbarossa, delayed partly because of the operation in the Balkans, had begun with such high hopes and dazzling victories. The fall of Kiev, Kharkov and Odessa, the besieging of Leningrad, the spearheads of the 7th Panzer Division in the suburbs of Moscow. Then had come the setbacks, culminating in a most reluctant Hitler suspending the assault of Heinz Guderian’s Panzers on the Soviet capital. This was coupled with the entry of the United States into the conflict in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the final abandonment of the plan to invade Great Britain, the first USAAF bombing raids on Germany, and Grossaktion Warschau of the summer of 1942. This had seen more than a quarter of a million Jews dispatched from the Warsaw ghetto to Treblinka, the extermination camp sixty miles north of the Polish capital. Then had come the shocking news of Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel’s defeat at El Alamein. After this maelstrom, more than ever Hitler relished the restorative powers of his Alpine retreat. The Germans called it Bergfried, the peace of the mountains.

Thirteen days earlier he had been at his eastern HQ in Rastenburg, Prussia, directing the deteriorating situation around the industrial centre of Stalingrad in south-western Russia. It was at this point – 6 November 1942 – that the first intelligence had filtered through of a large Allied naval force setting sail from Gibraltar. It was steaming east. Two days later Hitler was scheduled to be in Munich, the fount of the Nazi movement, to address the Party on the nineteenth anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch. Setting out in the command train after lunch on 7 November, Hitler arrived in the Bavarian capital at 3.40 p.m. – much delayed by stopping at every major station to hook up the train to the railway telegraph system to glean the latest news from the Mediterranean. By the time the Führersonderzug reached Munich’s main station, the Allied landings in French North Africa had begun. This was Operation Torch, under the overall command of the fifty-two-year-old from Kansas, General Dwight D. Eisenhower.

Opposition should have come in the form of 120,000 Vichy French troops under Admiral François Darlan. Their loyalty was questionable, the Allies even supposing that some Vichy elements would support the landing. Resistance in Morocco and Algiers proved tenacious in some places, sporadic elsewhere, but enough to see a death toll of just under 2,000 accruing to the two sides, the sinking of a number of ships, and Darlan himself declaring for the Allies, before the bridgeheads were established.

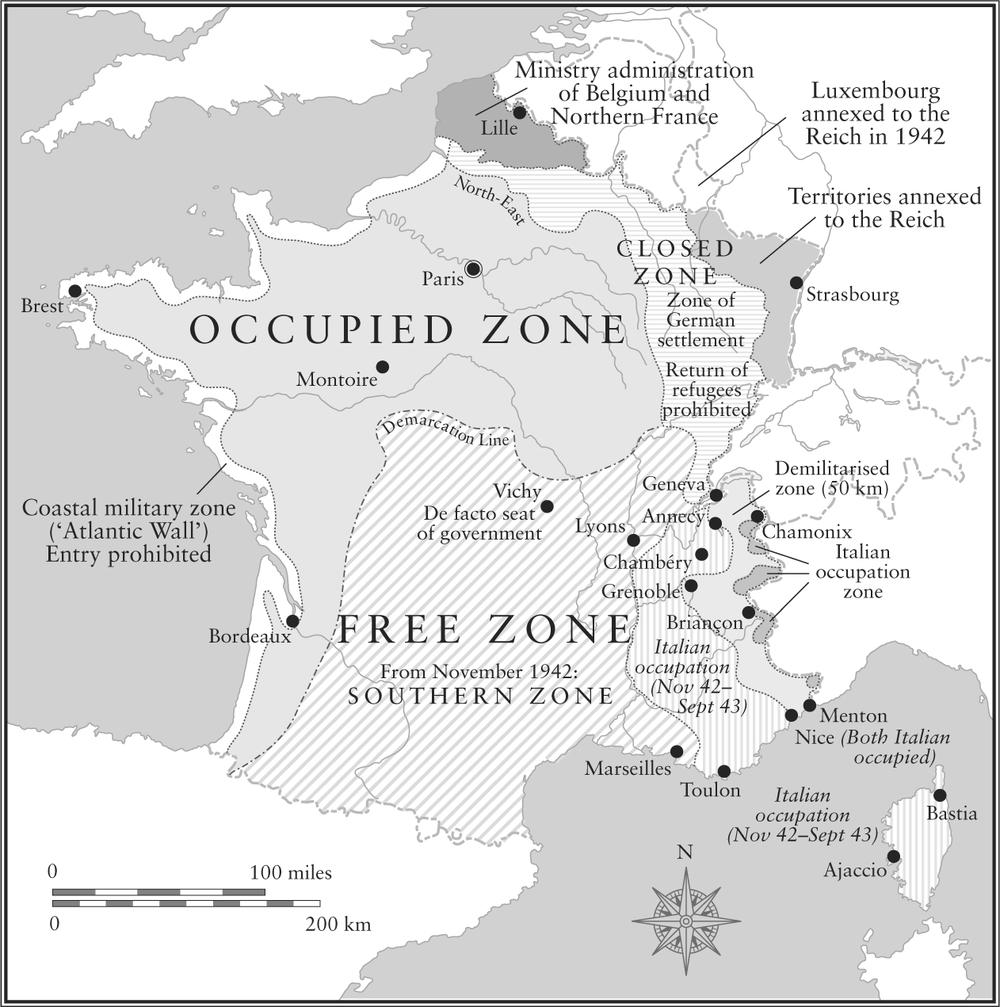

For Hitler, as he was driven to the Löwenbräukeller to address the Party faithful, the implications of the landings were obvious. With Rommel in retreat after Montgomery’s desert victory, the Axis forces in the whole North African theatre were now threatened: the balance of power in the Mediterranean had shifted dramatically in the Allies’ favour. Seven hundred miles away in Downing Street, Churchill took a similar line. On 10 November 1942 he famously told the Lord Mayor’s Luncheon at the Mansion House in the City of London, ‘Now this is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.’1 Both leaders saw that even Germany herself was imperilled if the Allies seized the opportunity to invade unoccupied southern France, the Zone Libre under the control of Pétain’s Vichy administration. From Algiers, the French Riviera was just a hop across the wine-dark Mediterranean. From the Riviera, Germany was virtually in sight.

Fall Anton – Operation Anton – had been thoughtfully developed by OKW for just such a contingency. This was the completion of the Third Reich’s occupation of France, the seizing of the Zone Libre, the margins of which were the country’s tempting Mediterranean coast and her Alpine border with Italy.

Now Hitler at once directed the plan to be dusted off. At 8.30 on the morning of 10 November – just as Churchill was rehearsing his speech – the Führer gave the order for Axis forces to defy the terms of the armistice with Vichy and occupy the Zone Libre. He excused the action by declaring, ‘After the treachery in North Africa, the reliability of French troops can no longer be guaranteed.’2

The implications for the French Alps along the border that zigzagged north from Nice to Geneva were far-reaching. The Italians had already occupied the fringes of this frontier area during the faltering campaign of June 1940. They had remained there under the terms of the Franco-Italian armistice. Now the Italian Fourth Army under the balding, bespectacled fifty-four-year-old Generale Mario Vercellino marched a further seventy-five miles west to Avignon in the south and Vienne in the north. The Italians assumed control of Nice itself, capital of the Alpes-Maritimes; further north in the Rhône-Alpes they took the capital of the ancient province of Dauphiné, Grenoble; Chambéry, the capital of Savoie; and Annecy, capital of the Haute-Savoie. In all, this was an area comprising eight départements.

Occupied Zones in France

Further north in the Alps, Vichy France’s border with Switzerland between Geneva and Basel – the départements of Ain, Jura, and Doubs – was seized by the German Seventh Army, so closing the fascist ring on the tiny democracy.

Having brazenly assured the junketing Nazis in the Löwenbräukeller that Stalingrad was firmly in the hands of Generalfeldmarschall Friedrich Paulus’s Sixth Army, Hitler had retreated south to the Berghof. Generalfeldmarschall Keitel, head of OKW, and his deputy Generaloberst Jodl were in attendance; also Albert Speer. The quartet ruminated on recent developments. The Allied landings – Operation Torch – were the culmination of the Reich’s setbacks in North Africa that had begun with the defeat of Rommel’s hitherto unvanquished Afrika Korps in the Western Desert at the Second Battle of El Alamein. On the Eastern Front, a counteroffensive from the Red Army was anticipated – though not on a scale that required the presence of Hitler and his entourage at Rastenburg.

It was on 19 November that a phone call came through to Obersalzberg from Rastenburg. The new Chief of Staff Generaloberst Kurt Zeitzler called with grave news. The forecast Russian attack – Operation Uranus – had begun. It was on a much greater scale than OKW had envisaged. Three armies under General Nikolay Vatutin were driving south on a 250-mile front in a transparent attempt to encircle Paulus’s Sixth Army in Stalingrad. The choice, said Zeitzler, was stark. Either a retreat to the west or be cut off. Hitler was outraged – not least because the forty-seven-year-old Zeitzler had been chosen to replace Generaloberst Franz Halder on the grounds that he would be both more robust and less dogmatic. Keitel, Jodl and Speer were also aghast.

The thirty-seven-year-old Albert Speer was the man unexpectedly spotlit by Hitler when he saw the architect’s designs for the 1933 Nuremberg party rally. It was Speer’s idea to hold the rallies at night to disguise the fact that many of the leading Nazis were overweight. Soon he became the principal architect to the Reich, the man who would blueprint Hitler’s dreams for a brave new Germany. The Reichskanzlei (Reich Chancellery) in Berlin was his first major triumph, Hitler having dismissed the old building in the Wilhelmstrasse as only ‘fit for a soap company’. Having so distinguished himself, Speer was singled out for a further remarkable promotion to the Reich’s arms and munitions minister. His supposed ignorance of the Final Solution to the Jewish question later led to the cognomen ‘the good Nazi’; and his astutely self-serving memoirs provide an intriguing insight into the upper echelons of the Reich as its narrative steadily unravelled.

On this occasion Speer pictured Hitler pacing back and forth like a caged animal in the great hall of the Berghof:

Our generals are making their old mistakes again. They always overestimate the strength of the Russians. According to all the front-line reports, the enemy’s human material is no longer sufficient. They are weakened; they have lost far too much blood. But of course nobody wants to accept such reports. Besides, how badly Russian officers are trained! No offensive can be organized with such officers. We know what it takes!3

The matter simmered for three days as the news from the east became worse and worse. Then Hitler, Keitel and Jodl once again entrained at Berchtesgaden on the Führersonderzug and rushed back to Rastenburg.

It was 22 November 1942. Ahead lay the siege of Stalingrad.

2

So to Switzerland. The complete closing of the Swiss border by Operation Anton ten days earlier meant that the republic was now completely surrounded by the Axis, all its frontiers effectively closed. This brought a series of problems in the country to a head. Principal amongst them was that of the Jewish refugees.

Like Great Britain, Switzerland had a long tradition of offering asylum to the oppressed. This was partly as a consequence of her geographical position at the crossroads of Europe, partly because of her traditional neutrality, partly – perhaps – because of the humanity of the Swiss people. The state had given sanctuary from religious persecution to the Huguenots and the Waldenses in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Geneva becoming known as the ‘Protestant Rome’. In the years of the French Revolution she had provided homes for her western neighbour’s royalists. In 1815 the international guarantee of her neutrality by the Congress of Vienna had cemented her reputation as the capital for asylum; in 1848, the European year of revolution, she had given sanctuary to politicians of all colours – this despite having undergone her own turmoil in the form of the Sonderbund civil war the previous year. In the twentieth century, Russian revolutionaries including Vladimir Lenin had found exile in the mountain state.

Yet despite this record, and despite being a multilingual and multicultural nation, it was often said that the Swiss had a strong sense of their own identity and no particular enthusiasm for outside influences or people. Alexander Rotenberg was a twenty-one-year-old Jew from Antwerp who escaped to Switzerland at the time of Operation Anton in autumn 1942. For Rotenberg, ‘The Swiss were not particularly anti-Semitic, but they tended to be xenophobic. They liked their own ways; foreigners, with the exception of tourists, made them feel uncomfortable.’4 Much more recently, in 2002, this perspective was echoed by Switzerland’s own landmark Bergier commission into the country’s wartime record: ‘Anti-Semitism was mostly unspoken and kept below the surface, but clearly ingrained in the social fabric.’5 This low-grade xenophobia, at the time commonplace throughout Europe, was manifested in a concern about ‘foreignerisation’, Überfremdung.

This debate was given increasing force as the number of refugees grew in the years preceding the outbreak of war. After the passing of the Nuremberg Laws in 1935 that deprived German Jews of their citizenship, the Reich had actively encouraged Jewish emigration. By 1938, one in four German Jews – some 150,000 – had left Germany, fleeing to where they could. Great Britain took 50,000, France 30,000, Poland 25,000, Belgium 12,000, the Scandinavian countries 5,000. Switzerland herself accepted 5,000. With the annexation of Austria in March 1938, Nazi policy became more concerted, and saw the establishment of ghettos and forced emigration. Pressure on Switzerland grew.

*

In the face of this policy and the practical implications for the liberal democracies that might be inclined to accept the Jews, in 1938 President Roosevelt had called an international conference on the question. Switzerland, at the time still the host country of the League of Nations, and in the immediate proximity of Germany, was the obvious venue. The Swiss declined the suggestion, supposedly fearing to offend Hitler. Évian-les-Bains, the French Alpine watering-place south across Lake Geneva from Lausanne, was chosen as a substitute. It was hoped that charity and justice would be dispensed along with the mineral water.

Here, from 6 to 14 July 1938, the liberal democracies disgraced themselves. The French hosts set the tone by stating that their country had reached ‘the extreme point of saturation as regards the admission of refugees’. Lord Winterton, leading the British delegation, followed suit: ‘the United Kingdom is not a country of immigration. It is highly industrialised, fully populated and is still faced with the problem of unemployment.’ The United States could do no better: it would not relax its strict immigration quota. The Swiss head of the police force responsible for foreigners, Dr Heinrich Rothmund, unapologetically told delegates that ‘Switzerland, which has as little use for these Jews as Germany, will take measures to protect herself from being swamped by Jews.’6

The consequence was that – at least officially – the enlightened democracies would do precious little to find new homes for the displaced Jews. In their defence, the extermination of the race first threatened by the Nazi SS chief, Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler, before the end of that year of 1938 was hardly an outcome imagined by the delegates. Nevertheless, the fact was that after Évian, as Chaim Weizmann, later Israel’s first head of state, commented, ‘The world seemed divided into two parts – those places where Jews could not live and those where they could not enter.’7

*

With the outbreak of war the pressure of Jewish refugees on the Swiss borders had risen.

In the Alps, Bavaria had been profoundly hostile to Jews since the promulgation of the Nuremberg Laws. In the resort of Garmish-Partenkirchen anti-Jewish posters were removed only on the occasion of the Winter Olympics in February 1936 – when they might be seen by international visitors; the twin towns’ remaining forty Jews were expelled at two hours’ notice during Kristallnacht on 9/10 November 1938. Two of them, turned back at the Swiss border, committed suicide. Austria’s Alpine provinces had kowtowed after Anschluss in March 1938, the resort of Kitzbühel seeing its Jewish community disappear virtually overnight. After the Fall of France, Vichy had required no prompting from Berlin to pass the Statut des Juifs: the internment camp in the Paris suburb of Drancy had opened on 21 August 1941. Following the Wannsee Conference in January 1942 in Berlin which formulated ‘die Endlösung der Judenfrage’ (the Final Solution to the Jewish question), the persecution of the French Jewish population became more concerted. The Vel d’Hiv round-up of Jews in central Paris in July 1942 saw the first 13,000 of a total of 67,400 sent to Auschwitz. The French Alpine regions of the Rhône-Alpes and the Alpes-Maritimes soon followed. Nice lost 600 Jews on 26 August 1942; in Grenoble, capital of the Dauphiné, the community of around 3,000 Jews also found themselves persecuted, then – eventually – deported. In the Italian Alps, Mussolini’s pale imitation of the Nuremberg Laws, the Manifesto della razza, held sway from September 1938. In Piedmont, persecution was sufficient to drive families into hiding in the surrounding mountains; deportations to Auschwitz began in 1942. In the Yugoslav Alps, Nazi anti-Semitic policies were pursued with their usual vigour after the Axis invasion of April 1941, though those parts of the country held by the Italians were less harsh in their treatment. By 1942, much of the Alps had become a place where Jews could not live.

Switzerland therefore became the obvious destination for the persecuted. Yet despite its tradition of offering asylum for the oppressed, the Swiss were cautious. They categorised those trying to enter Switzerland as Evaders (military personnel in plain clothes), Internierten (military personnel clothed as such) and Flüchtlinge – civilian refugees. They filtered and they sifted. In the aftermath of the Évian Conference the Swiss successfully petitioned the Nazis to stamp the passports of Jews with a J, a decision approved by the Federal Council on 4 October 1938. This was to enable them to be singled out at the border. As the Bergier commission pointed out, this meant that Switzerland was ‘making anti-semitic laws the basis of its entry practices’.8

By 1941 the country was playing host to 19,429 Jews, of whom 9,150 were classed as ‘foreign’. Some were en route to other countries, others had nowhere else to go. As the consequences of Wannsee became apparent, the refugees’ problem became desperate. By the summer of 1942, the fate of Jews sent east in the railway cattle cars – the story of Treblinka – had found its way into the press. Both the Daily Telegraph in England and the Washington Post in the United States carried stories of the mass exterminations. On 25 August 1942 the story was splashed all over the Swiss newspapers, and the Swiss found themselves besieged. Already, in late July 1942, Heinrich Rothmund had written to his superior, the Justice and Police Minister Eduard von Steiger,

What are we to do? We admit deserters as well as escaped prisoners of war as long as the number of those who cannot proceed further [to other countries] does not rise too high. Political fugitives … within the Federal Council’s 1933 definition are also given asylum. But this 1933 ordinance has virtually become a farce today because every refugee is already in danger of death … Shall we send back only the Jews? This seems to be almost forced upon us.9

To avoid the appearance of persecuting the Jews, on 13 August 1942 Steiger agreed to Rothmund ordering the closing of Swiss borders to all refugees, irrespective of nationality or race. In a speech at the end of the month, von Steiger explained,

Whoever commands a small lifeboat of limited capacity that is already quite full, and with an equally limited amount of provisions, when thousands of victims of a sunken ship scream to be saved, must appear hard when he cannot take everyone. And yet he is still humane when he warns early against false hopes and tries to save at least those he has taken in.10

This was generally interpreted in the headline ‘DAS BOOT IST VOLL’ (The boat is full), a phrase used both by the Swiss President and by Rothmund himself.

The judgement of history on this decision has been harsh. The Bergier commission noted the democracy’s failure to distinguish between war and genocide. It also judged that the country ‘rarely chose’ to use its position ‘for the defence of basic humanitarian values’.11

For the Swiss, Operation Anton, less than three months after Steiger’s August decision, was a body blow. From 1940 onwards the republic’s ambivalence towards refugees had been coupled with the practical difficulty of the shortage of food for an increasing number of mouths, together with fears of social and political unrest. While the refugees remained birds of passage, this was not an overwhelming problem even for a small country with limited food for its own population. The closure of the border caused by Operation Anton exacerbated the crisis, both in terms of perception and reality. It was one thing to be a staging post for refugees. It was another to accept them at the frontier without any prospect of their eventual departure. As Alexander Rotenberg put it, when Switzerland was encircled, ‘Refugees, at first a novelty, were also by now streaming in from wherever they could find leaks in the border … And now, surrounded and closed off from free world trade, sharing short rations with illegal foreigners was not a popular option.’ Switzerland would soon be full, complet, besetzt, pieno.

In the autumn of 1942, in a country averse to strangers, in a nation whose very existence was in jeopardy, in a land where the population was on rations, they were the unwanted.

3

In practice the reception of Jews of any age or status often depended on the charity – or otherwise – of the border officials whom they encountered. Some refugees were turned away at the Swiss frontier and sent to their deaths. Others were formally admitted. To yet others a blind eye was turned. Rotenberg recorded his experience in Emissaries: A Memoir of the Riviera, Haute-Savoie, Switzerland, and World War II.12

In 1940 he had flown a Nazi round-up of Jews in his newly occupied home city of Antwerp. He had escaped first into occupied northern France, subsequently to the first port of call for many European Jews that summer: the Alpes-Maritimes capital of Nice. Here he lived for eighteen months working for the Jewish underground. Forewarned of the general round-up of Jews in the city of 26 August 1942, he took a train north into the Haute-Savoie in the Rhône-Alpes.

Then, as summer turned to autumn, he and a companion, Ruth Hepner, took the steep, rough mountain paths that led up to the Franco-Swiss border close to the French hamlet of Barbère. This was ten miles north-east of the famous old Savoie resort of Chamonix, at the foot of Mont Blanc, and at a height of more than 4,000 feet. It was a bleak and forbidding place, a world of bare rock and broken stones, bereft of vegetation, of human habitation and of pity.

Sucessfully avoiding the Swiss police patrols on the frontier, the pair scrambled down the mountainside towards what they hoped would be the safety of the Swiss village of Finhaut, Canton Valais. There they intended to throw themselves on the mercy of the occupants of the first chalet they could find. This, as they knew, was risky, for – in Rotenberg’s words – ‘The border patrols had grown more hardened.’13

As it so happened, Rotenberg and Hepner chanced upon the home of an army officer, First Lieutenant Emile Gysin. His wife Marguerite was welcoming and plied the pair with café au lait in front of the fire; when her husband returned – complete with a giant mastiff – he was furious. He at once assumed the refugees were German spies and threatened to turn them back to Vichy. ‘Why shouldn’t I arrest you right now? Can you prove to me you are not spies? And even at that – if you are refugees as you claim – I am supposed to turn you back.’ Rotenberg was cornered. How could Gysin be convinced? With a flash of inspiration, the answer came to him. He burrowed in his knapsack and brought out two prizes. These were a Hebrew prayer book and his tefillin, the set of phylacteries – boxes containing parchment inscribed with verses from the Torah – with which he prayed. ‘Have you seen these before?’ demanded Rotenberg of his host. ‘Do you know what they are?’

Gysin did indeed know. The ceremonial objects convinced the lieutenant of the bona fides of the pair, and he at once relented:

My orders are to arrest you, to return all single people to the French. But I will not. No. Absolutely not. I have seen what has happened in the valley, in Le Châtelard, at the border, where Jewish people have been forcibly handed over to the Vichy gendarmes, servants of the Boches, knowing full well what would happen to them. Inhuman indeed. It cannot be believed.14

Rotenberg was sent by these two good Samaritans to Montreux on the northern shores of Lake Geneva. Here he would be safe because the Swiss authorities would only expel Jews caught within five miles of the frontier. As he had sought sanctuary in Switzerland he was categorised as a ‘Flüchtling’. This meant he would be sent to a labour camp: initially at Girenbad in Canton Zurich.

Rotenberg was lucky. He joined a group of foreign Jewish refugees in Switzerland that by the time of Operation Anton in November 1942 totalled 14,000. ‘For each one of us,’ Rotenberg wrote of that time, ‘there were tens, hundreds, thousands who we knew had been hounded, tricked, duped, caught, torn from families, killed on the spot …’ As he learned in the course of his stay in the Swiss work camps, his mother and sister Eva were amongst them.

4

Rotenberg had managed to escape to Switzerland over the Alps. Other Jews in France at the time of Operation Anton found refuge in the mountains themselves.

In the south-east of France on the Riviera, the operation had seen the Germans seizing the territory to the west of the Rhône, taking their local headquarters at Marseilles on the river mouth. As we have seen, the Italians had taken over to the east of the river along the coast to Nice itself, and the Alpine border running north to Geneva. This arrangement seemed a very welcome development to the Jewish community in the Alpes-Maritimes and Rhône-Alpes, for it freed them from the strictures of Vichy’s Statut des Juifs that had already seen persecution and deportations. If it was true that some amongst the Italians were themselves anti-Semitic, anti-Semitism was not the centrepiece of Italian Fascism, and Italy’s anti-Semitic laws were relatively lenient. Moreover, in the Alpes-Maritimes the law was exercised without a great deal of vigour: its strictures were tempered both by the humanity of the Catholic Church and the desire of the Italians to have their own way in France. ‘The arrival of Italian soldiers in the departements east of the Rhône was generally received with satisfaction and with a feeling of relief among Jews in southern France.’15

At first this sentiment seemed well founded. In the first few weeks after Operation Anton, the Italian Carabinieri protected Nice’s Jewish monuments and even broke up a march of French anti-Semites on a synagogue. Yet it soon emerged that the situation was not as clear-cut as it seemed. The demarcation between the Italian and German authorities on the one hand and the remaining Vichy officials on the other was vague, ill-defined and – very shortly – quarrelsome.

No sooner had the Germans settled themselves in Marseilles in the early winter of 1942 than they began rounding up the local Jewish population. They also urged their Italian counterparts in Nice to do likewise. The Italians proved resistant. On 17 December 1942 Mussolini had heard the simultaneous declaration from the Allies in London, Washington and Moscow condemning the Nazis’ ‘bestial policy of cold-blooded extermination’,16 and drew the logical conclusion. That same month the Italian authorities prevented Vichy attempts in Nice to have the Jews’ passports stamped with the letter J for Juif or Juive; they then began interfering with the round-ups being undertaken by the Germans. On 22 February 1943 the Pusteria Division of the Italian Fourth Army had stopped the prefect of Lyons arresting 2,000–3,000 Polish Jews in the Grenoble area to the south-east of France’s second city. There was also an extraordinary stand-off between the Axis allies in Annecy. Here the Vichy authorities had rounded up a group of Jews in the local prison for deportation. The Italians set up a military zone in the prison precincts and got them released.

This was all too much. Reich foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop was obliged to call a meeting with Mussolini, complaining of this outrageous partiality. This was held on 17 March 1943. Il Duce, mindful of the Allies’ views on the extermination camps, diplomatically appointed the former police chief of the Adriatic city of Bari, Guido Lospinoso, as ‘Inspector General of Racial Policy’. His job was to deal with the Jewish question. This, believed Lospinoso, was a matter for the Italian authorities, not the Germans. In any case, he found little to be said in favour of forced deportation of the Jewish inhabitants to ‘the east’. The Allies’ declaration meant that no one could plead ignorance of the likely fate of such people; it was now increasingly uncertain that Italy would continue the struggle on the side of the Axis; and the Sixth Army had been all but annihilated at Stalingrad. Caution was wise.

Accordingly, on his arrival in Nice, Lospinoso adopted the Vichy practice of ‘assigned residence’, ‘résidence forcée’. This required individuals to live in a particular location under police surveillance. Lospinoso’s difficulty was to find somewhere within his area of jurisdiction where the Jews could be accommodated without excessive preparatory effort, expenditure of human resources and monetary expense. He hit upon the idea of the high Alpine resorts on the Franco-Italian border. These were places that – as the Swiss had realised – had the additional advantage of being prisons without walls. They were remote enough and in inhospitable enough terrain for escape to be impracticable for all but the most determined.

*

Lospinoso’s first choices that spring were Megève and nearby St Gervais in the Haute-Savoie. Part of the ancient Duchy of Savoie, this was the Alpine département lying 250 miles north of Nice in the Rhône-Alpes, on the southern side of Lake Geneva. Megève, a 3,369-foot resort ten miles east of Mont Blanc, in a sense selected itself. It was a medieval farming village developed as a skiing resort by the Rothschild family. The Jewish banking dynasty had tired of St Moritz in the years immediately before and after the First World War. Megève showed some promise as a substitute. It commanded a large, sunny bowl below the flanks of Mont Blanc that flattered the skiing of beginners, and it was easily accessible from Geneva. As skiing snowballed in the 1920s, the resort flourished. It attracted just the sort of set to whom St Moritz itself appealed: aristocrats, financiers and film stars: haute volée – high society. Now, in a turn of events not anticipated by the Rothschilds, the bankers were going to be supplanted by refugees.

The next challenge for Lospinoso was to move the 400 Jews from Nice to the Haute-Savoie. Rail was the obvious option to transport the thousands the Inspector General needed to resettle. However, to avoid the gradients of the Alpine terrain, the line from Nice ran west along the coast through the honeypots of Antibes, Cannes and St Raphael to Marseilles, before turning north to Grenoble and thence north-east to Savoie. All three sides of this rough oblong would take the Jews through territory held by German forces. Neither the Italians nor the refugees themselves would run this risk. Nobody knew how the Germans would react. Morale in the Wehrmacht had been badly hit by the final destruction of Paulus’s Sixth Army in Stalingrad at the end of January 1943.

Fortunately, a committee had been established in Nice to look after the refugees’ affairs and represent the community to the local authorities – now including the Italians. The Comité d’Assistance aux Refugés had provided the Jews with the papers necessary for survival in wartime Europe: identity cards, ration books and housing permits. Now it was able to secure the funding from the community itself to pay for lorries to take the refugees north by road to the Haute-Savoie. These were lumbering gazogènes, developed to run on charcoal in the absence of very heavily rationed petrol. Going uphill, passengers had to get out and push. The first convoys arrived in Megève on 8 April 1943. Just four days previously, a new crematorium – the fifth – had opened at Auschwitz.

As the days lengthened and the snows melted in the mountains, as the spring flowers blossomed, Lospinoso established similar communities in other Alpine resorts as far from the Germans and as close to the Italian border as possible. These were roughly on the north–south line between Megève and Nice: at Barcelonnette, Vence, Venanson, Castellane and Saint-Martin-Vésubie.

The last of these was only half a day’s drive north of Nice, a remote 2,346-foot settlement where the village and its stone houses seemed to cling to the edge of a precipice. Between the wars Saint-Martin had been fashionable among the English escaping from the heat of the summer Riviera; in nearby Roquebillière in 1939, Arthur Koestler wrote his masterly critique of totalitarianism, Darkness at Noon. Now, courtesy of Lospinoso, the 1,650 locals were joined by more than 1,200 Jews. In the words of a Polish refugee:

Saint Martin, a small settlement in the mountains some sixty kilometres from Nice, was before the war a holiday and convalescence resort. There the Italian occupation authorities have set up one of the places of résidence forcée for the Jewish refugees who have reached France during the war from countries occupied by the Germans. Here the refugees were accommodated in houses and villas. Twice daily they have to report to the police officers; they are also not allowed to go outside the village or to leave it … They are well organized: a Jewish committee elected by the refugees is responsible to the Italian authorities. They have schools for their children and there is also a Zionist youth movement. Despite the state of emergency life goes on normally, and thanks to the young Zionists cultural life is very well developed. Of course the refugees do not have the right to take jobs. The rich ones live off the money they have succeeded in saving from the Germans and the poor receive assistance from the committee.17

Somehow these communities maintained a sense of normality, even happiness, in the face of death. They had been dispatched like the unwanted goods they were into the high Alps to eke out an existence in that epic country, never knowing when a change in the fortunes of war would bring catastrophe.

There was another warning just as the first of the refugees settled into Megève in that spring of 1943. Following the extraordinary stand-off in February in nearby Annecy, the Italians had prevented a similar round-up of Jews in Chambéry in the Savoie. Should the French or indeed the Germans gain the upper hand, the refugees would obviously be on their way to Auschwitz. Who could tell what might happen next?

5

Over the nearby border in Switzerland, Alexander Rotenberg in his work camp was in a place of greater safety, but that spring of 1943 Switzerland was once again by no means secure.

In March 1943, four months after his abrupt departure from Berchtesgaden to save Paulus’s army at Stalingrad, Hitler was to return from Rastenburg to Bavaria. In preparation for his stay in Obersalzberg the Berghof was given a spring clean, the terrace that overlooked the Alps of Berchtesgadener Land was cleared of snow, and the colourful parasols were dusted off. The Führer would be accompanied by his entourage: Generalfeldmarschall Keitel and Generaloberst Jodl were to be joined by the staffs of Göring, Himmler and von Ribbentrop. With patchy snow still on the ground, the Nazi leaders would settle themselves into Obersalzberg, spreading out into the nearby resort of Bad Reichenhall and the city of Salzburg. Here, warming themselves in front of blazing log fires, they would once again plot Switzerland’s demise.

Yet first – on their arrival – they discovered that Obersalzberg was beginning to reflect the deteriorating course of the Reich’s war. It was no longer quite the sanctuary they sought. Berchtesgaden, hitherto considered inviolable, was now thought to be increasingly vulnerable to Allied air raids. By the time of Hitler’s return to the Berghof that March of 1943, Reichsleiter Bormann was already drawing up plans for an elaborate bunker system. The underground accommodation included quarters for the Führer’s Alsatian, Blondi. (According to Speer, ‘The dog probably occupied the most important role in Hitler’s private life; he meant more to his master than the Führer’s closest associates … I avoided, as did any reasonably prudent visitor to Hitler, arousing any feelings of friendship in the dog.’)18

Equally unsettling were the wounded. The pressure on army hospitals throughout the Reich was now such that the Hotel Platterhof, intended to accommodate dignitaries visiting the Führer at the Berghof, had been converted into a hospital. Irmgard Paul, the girl who, as a three-year-old, had been dandled on Hitler’s knee, was one of the Kindergruppe invited to put on a play that spring for the injured. The children performed Sleeping Beauty to great applause, but Irmgard remembered that she ‘could not take my eyes off the young men with their thick, white head bandages, moving along slowly on crutches, arms in slings and legs in casts or missing entire limbs. I felt slightly sick and hoped fervently they would all get well, but wondered what on earth they would do with only one arm, one leg, or no legs.’19

It was in this atmosphere that Hitler’s general staff began to scheme and plan.

After the calamity at Stalingrad of barely a month previously, and with Anglo-American forces from the Operation Torch landings now pushing back strongly against Rommel’s Axis forces in Tunisia, the German army was in retreat. On 14 March – just before his return to Obersalzberg – Hitler had voiced his fear that ‘the loss of Tunisia will also mean the loss of Italy’.20 This in turn might give the Allies easy access to the Alps – and thence to Germany herself.

His staff had accordingly conceived the idea of a strategic retreat into those parts of central and western Europe that could be easily defended. This was the notion of ‘Fortress Europe’. Of this, Switzerland and her mountains formed an integral part. The plan would incorporate the Swiss Alps into a defensive system joining General Guisan’s Alpine Redoubt with the Black Forest, the Austrian Arlberg with the Bavarian Alps, the Brenner Pass with the Italian Dolomites. As to its practical execution in terms of seizing Switzerland, one imaginative option dated from July 1941. This was Operation Wartegau.21 It called for a commando force assembled in flying boats on the Bodensee (Lake Constance) to be flown south-west the short distance to the Swiss lakes of Lucerne, Thun and Zurich. That would surprise the Swiss!

The Swiss had a source of intelligence actually within the German high command. On 19 March 1943, the agent known as the ‘Wiking line’ dispatched the most alarming of news to Berne. General Guisan was immediately alerted. German mountain troops, the Gebirgsjäger, were massing in Bavaria; General Eduard Dietl, a mountain warfare specialist, had been flown from occupied Finland to a specially established HQ in Munich to mastermind the operation. Invasion yet again seemed imminent, and Guisan at once mobilised his civilian army. The Swiss called it the März-Alarm.

Notes

1. Martin Gilbert, Churchill: A Life (London: Heinemann, 1991).

2. Wilhelm Deist, Germany and the Second World War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990).

3. Albert Speer, Inside the Third Reich (New York: Macmillan, 1970).

4. Alexander Rotenberg, Emissaries: A Memoir of the Riviera, Haute-Savoie, Switzerland, and World War II (Secaucus, NJ: Citadel Press, 1987).

5. Independent Commission of Experts Switzerland – Second World War (ICE), Switzerland, National Socialism and the Second World War: Final Report (Munich: Pendo, 2002)

6. Christopher Sykes, Crossroads to Israel (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1973).

7. Sykes.

8. ICE.

9. Kimche.

10. Kimche.

11. ICE.

12. Rotenberg.

13. Rotenberg.

14. Rotenberg.

15. Daniel Carpi, Between Mussolini and Hitler: The Jews and the Italian Authorities in France and Tunisia (Hanover, NH, and London: Brandeis University Press, 1994).

16. Gilbert, Churchill: A Life.

17. Susan Zuccotti, Holocaust Odysseys (New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, 2007).

18. Speer.

19. Hunt.

20. Deist.

21. Halbrook, Swiss and the Nazis.