CHAPTER TWO

Wage and Price Controls

Bad Economics Brings Bad Policy

IN 1970, Penn Central, a large financial holding and transportation company that had mismanaged its affairs, was about to file for bankruptcy. Arthur Burns, who was chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, had been chairman of President Eisenhower’s Council of Economic Advisers. Burns was widely regarded as both a talented economist and an effective Washington operator. Helmut Schmidt, who would later become the chancellor of West Germany, was said to regard Arthur as the “pope of economics”—in other words, infallible.

Burns thought that if Penn Central went bankrupt there would be a great shock to the financial system. His unorthodox solution to this, which he had somehow arranged with a reluctant David Packard at the Pentagon, was what amounted to a bailout for Penn Central using Department of Defense–guaranteed V-loans. These were intended to be used by military contractors, but the company had argued it should qualify given the national security dimensions of its railroad freight operations. It was a bad idea, as it would undermine the sense of accountability for one’s actions in the financial system. At a critical moment in a White House discussion of the bailout, George Shultz, who was director of the Office of Management and Budget, recalls that into the room came President Nixon’s savvy political adviser Bryce Harlow, who said, “Mr. President, in its infinite wisdom, the Penn Central Company has just hired your old law firm to represent them in this matter. Under the circumstances, you can’t touch this with a ten-foot pole.” So there was no bailout. The Penn Central failed … and guess what? The financial system was strengthened because others saw they had better get their houses in order. So the deep virtue of accountability was kept alive. Reflecting on all this, you could see that Schmidt was wrong: as impressive as he was, Arthur Burns was not infallible.

But people in Washington were talking more about inflation being intractable, and the wage and price controls were being suggested as an answer. You could sense that wage and price controls were in the air. So a speech by Shultz made the case that the budget was under control and, with a reasonable monetary policy, inflation would be brought under control. All one needed was the patience to see these policies through, so the title of the speech was “Steady As You Go.” The following passage summarizes the speech:

A portion of the battle against inflation is now over; time and the guts to take the time, not additional medicine, are required for the sickness to disappear. We should now follow a noninflationary path back to full employment.23

Office of Management and Budget director George Shultz and Fed chair Arthur Burns wrestle over whether to “do something” about inflation on the cover of Time magazine, August 16, 1971, the week phase I wage and price controls were enacted. From TIME. © 1971 TIME USA LLC. All rights reserved. Used under license.

In August 1971, President Nixon announced a sixty-day wage-price freeze that was to be followed by wage and price controls. So the guideposts of the 1960s, which Friedman and Solow debated, became wage and price controls in the 1970s. This development can be understood better now than it was then: in 2018, research in the Hoover Archives revealed a letter from Arthur Burns, writing as chairman of the Federal Reserve at the time, to President Nixon. In his letter, dated June 22, 1971, Burns argued that structural changes in the economy made it difficult to control inflation, that sound monetary and fiscal policies—classical policies—would not work as in the past, and that a new approach was needed. He advocated a six-month wage and price freeze. In this private letter to the president, Burns was advocating wage and price controls. Obviously, he thought they would work, giving the Fed a major assist in taming inflation. He was an expert in the business cycle, with many years conducting research at the National Bureau of Economic Research, and this was a surprising change in his thinking. This letter, which has never before been published, is included in this volume as appendix B. Here are some key paragraphs:

1. In my judgment, some of us are continuing to interpret the economic world on the model of the 1940s and 1950s. In fact, the structure of the economy has changed profoundly since then.

There was a time when the onset of a business recession was typically followed in a few months by a decline in the price level and in wage rates, or at least by a moderation of the rise. That is no longer the case. The business cycle is still alive, indeed too much so; but its inner response mechanism, which has never stood still, is now very different from what it was even ten or twenty years ago.

Failure to perceive this may be responsible for some shortcomings in our national economic policy. I doubt if we will bring inflation under control, or even get a satisfactory expansion going, without a major shift in economic policy.

2. The first requirement of a new economic policy is recognition of the uneasiness that characterizes the economic world—an uneasiness that is slowing the business recovery and which may continue to impede it in this year and next.

Consumers are saving at a high rate, partly because of existing unemployment and partly because of concern about what inflation is doing to their incomes and savings.

There is also a mood of hesitation among businessmen. They see their wage costs accelerating, they fear that they will be unable to raise their prices sufficiently to cover their higher costs, and—with profits already sharply eroded and interest rates high—many hesitate about undertaking new investments. It is important to note that business capital investment, in real terms, has been declining in the present economic recovery; this is very unusual for this stage of the business cycle.

3. As you already know, I have reluctantly come to the conclusion that our monetary and fiscal policies have not been working as expected; they have not broken the back of inflation, nor are they stimulating economic activity as expected.…

I am convinced that the restoration of confidence requires, above everything else, a firm governmental policy with regard to inflation. With this achieved, our economy can move forward towards full employment. Without it, we may stumble—perhaps stumble all the more if we try a more expansive monetary or fiscal policy.

4. What I recommend, as a way out of the present economic malaise, is a strong wage and price policy.

I have already outlined to you a possible path for such a policy—emphatic and pointed jawboning, followed by a wage and price review board (preferably through the instrumentality of the Cabinet Committee on Economic Policy); and in the event of insufficient success (which is now more probable than it would have been a year or two ago), followed—perhaps no later than next January—by a six-month wage and price freeze.

Some such plan as this is, I believe, essential to come to grips with the twin problems of inflation and unemployment.

A firm wage and price policy will not get at the basic problem—the abuse of economic power. But the kind of legislation that would be needed will not be passed in the next year or two.

The wage-price freeze was very popular at first, a frightening development, as the natural flow of economic variables in the economy was being stifled. The stock market logged one of its best days ever. A number of economists, published in the Wall Street Journal and in Newsweek argued meanwhile against the freeze. Friedman was quoted in Newsweek as saying: “[President Nixon] has a tiger by the tail. Reluctant as he was to grasp it, he will find it hard to let go.”24

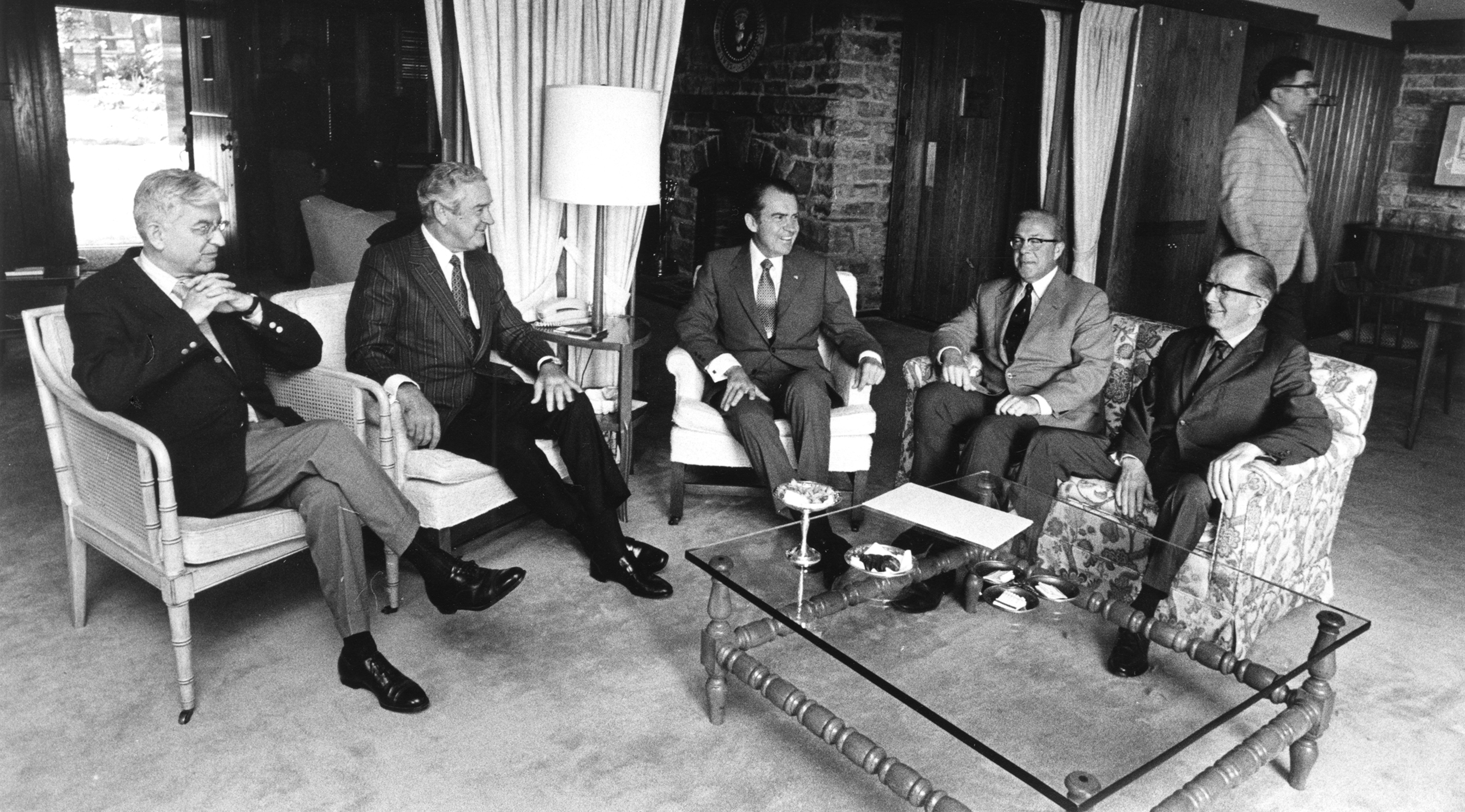

(From left) Federal Reserve chairman Arthur Burns, Treasury secretary John Connally, President Richard Nixon, Office of Management and Budget director George Shultz, and Council of Economic Advisers chair Paul McCracken at Camp David in August 1971, the weekend before unveiling the president’s New Economic Program wage and price controls. Participants were instructed not to tell their families where they were headed in order to maintain the secrecy (and the theatrical nature) of the discussions. Having lost the argument against controls, McCracken would resign following the president’s announcement. Ollie Atkins for the White House. George Pratt Shultz papers, Box 732, Hoover Institution Archives.

Political responses varied. A year earlier in August 1970, amid public concerns on rising inflation, the Democratic-controlled Congress had passed the Economic Stabilization Act, giving the president the authority to stabilize prices, rents, and wages, which was interpreted inside the administration as a sort of dare. To take a sample from the AP newswires on August 17, 1971, in the Washington, DC, area, it was unsurprising, for example, to see Virginia Democratic senator William Spong Jr. arguing, “The measures taken by the President were long overdue.… I advocated a freeze on wages and prices 18 months ago and I commend the President for taking this action.”25 But the state’s Republican governor, Linwood Holton, also agreed:

[The President] has taken a bold and positive action. I am very optimistic about the impact this action will have on the economy. He is doing everything which both labor and business have recommended.… I look forward to a material improvement in the unemployment situation and a restoration of consumer confidence.26

Independent senator Harry Byrd was more measured, saying, “The sweeping economic actions and proposals advanced by President Nixon will require close study before firm judgment can be made. Drastic action was made inevitable by swelling government deficits encouraged by both the Congress and the President.”27

Corporate sentiment was similarly mixed. Richard Reynolds Jr., president of the Reynolds Metals Company, enthusiastically described the 1971 freeze:

A very good and forceful move at a critical time.… The President’s program is going to help the economy generally and basic industries, including aluminum, in particular. His action was certainly warranted by the condition of the economy. We don’t have the demand.… It is quite clear that the President deserves praise for the scope of this action.28

Claiborne Robins, chairman and chief executive officer of A. H. Robins pharmaceutical company, meanwhile looked ahead, with some doubt, stating, “I think this probably is a good move for the short term, but over the long run I doubt controls are either effective or desirable.”29

At first, the wage-price freeze seemed to work, and it came at a time when inflation was in the process of declining and commodity prices were soft in the world markets. The freeze was inevitably followed up by explicit, compulsory wage and price controls, which turned out to be very intrusive in the economy. People were unable to change wages and prices without the consent of the so-called Price Commission or Pay Board. The controls were administered with enthusiasm by a Cost of Living Council headed by John Connally, secretary of the Treasury.

In the short term, the consumer price index, which measures inflation, declined and real GDP rose. All this led to the landslide reelection of President Nixon. But trouble lay ahead. The economy sputtered, and prices were a problem. The Cost of Living Council, the bureaucracy responsible for administering the controls, was intrusive. No wage or price change could take place without approval by the Pay Board or the Price Commission, so the gears of the economy ceased working in the normal and natural way that produces an efficient system.

NOTES

23. George P. Shultz, “Prescription for Economic Policy: ‘Steady As You Go’ ” (speech, Meeting of the Economic Club of Chicago, Chicago, IL, April 22, 1971).

24. Milton Friedman, “Why the Freeze Is a Mistake,” Newsweek, August 30, 1971.

25. “Holton Calls Nixon Move Bold,” Associated Press, August 17, 1971.

26. “Holton Calls Nixon Move Bold,” Associated Press.

27. “Holton Calls Nixon Move Bold,” Associated Press.

28. Walter Stovall, “Banks, Firms Laud Nixon Move,” Associated Press, August 17, 1971.

29. Stovall, “Banks, Firms Laud Nixon Move.”