CHAPTER THREE

Damage Control as the Economy Fights Back

SHULTZ BECAME secretary of the Treasury on June 12, 1972. The exchange rate system was in disarray after Nixon closed the gold window, a promise to buy gold with dollars at a fixed price, on August 15, 1971. An effort to reconstruct a fixed exchange rate par value system, known as the Smithsonian Agreement, had failed. With Friedman’s help, Shultz designed a floating rate system in the clothing of a par value system, which the Europeans wanted. That proposal was put forward as the US position at a World Bank–IMF meeting. While it was never exactly implemented, the result might be called a managed float system. The nut of it was that exchange rates were, in effect, decontrolled. In the end, that worked reasonably well. So that left us with a market-based international system for currencies and a wage and price control system in the United States.

Meanwhile, the Cost of Living Council, now headed by Don Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney, reported to Shultz. But pushback was growing. Shultz’s friend J. Willard Marriott, chairman of the board of Marriott Hotels, wrote to Shultz on January 15, 1973:

The red tape which has involved numerous accountants, lawyers, discussions and meetings to get a legitimate price increase is impossible to explain to you. There is only one really fair way our industry can be handled and that is to release us from wage and price control and let us operate within the range of our fair profit situation. Our business is so competitive not only with other competitors, but especially with the housewife. And without having to fight continuously with the government, we have our hands full even keeping alive in our competitive market.

It is, I think, extremely obvious without looking at the figures that it is extremely unfair to control the retail prices of industry without controlling the wholesale prices, especially in the food industry where tremendous increases have occurred almost weekly in farm and wholesale prices.30

George Shultz and Milton Friedman with President Nixon in the summer of 1971. Milton Friedman papers, Box 115, Folder 4, Hoover Institution Archives.

Later that year, on November 2, 1973, then secretary of commerce Frederick Dent wrote to the president reporting on a meeting he had had with labor and business leaders:

The first comments were made by a business representative and were directed to the necessity for decontrolling wages and prices. The ensuing general discussion on this topic brought out the following points:

- The wage and price program is creating an undue number of shortages in the economy, which can only be restored through free market actions.

- Selective decontrol will not work because industries are too highly interrelated. A general decontrol action is favored.

- To successfully accomplish decontrol, the people must be informed of the effects of controls, the reasons for decontrol, and the anticipated market response, while at the same time asking for their support and forbearance in achieving the essential goal.31

Shultz, Rumsfeld, and Cheney all thought it was time to ease up on the controls. They knew that inflation was suppressed, not eliminated, by controls, so they warned the president that probably there would be a slight uptick as the controls were eased up. This became known as phase III of the wage and price control system (see appendix D), which abolished the Price Commission and the Pay Board in favor of “self-administration” by obligated firms. But when the uptick came, Nixon decided to reimpose controls.

One humorous sideline to all this was a discussion in which Herb Stein, chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers, said to the president, referring to the popularity of the earlier wage-price freeze: “Mr. President, you can’t walk on water twice,” to which President Nixon replied, “You can if it’s frozen.” It was clear then where policy was headed.

Facing public outcry and political pressure, President Nixon reimposed price controls in June 1973 through a new sixty-day price freeze, beginning phase IV of the program, while simultaneously warning the American public against becoming addicted to the tool. Shultz had to say to the president, “This is your call, but it’s directly opposed to my advice and I think you are making a mistake. Under the circumstances, you need to find a new secretary of the Treasury.”

President Nixon accepted the reality but asked Shultz to stay on since Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev was coming to Washington. Shultz had managed the US-Soviet economic relationship. That turned out to be very educational and useful, particularly when Shultz returned to government service in 1982 as secretary of state. For example, while Nixon didn’t care for economics, he wanted to bring Brezhnev to California for security talks, so he made it possible to take the Soviet economists to Camp David for a weekend. While there, the Soviet economists engaged in lots of informal talk among themselves about their country’s economy. They knew Shultz didn’t speak Russian, so they talked freely. They didn’t seem to realize that the US interpreter was also in the room, and he later gave a candid view of how poorly the Soviet experts thought their economy was working. This ended up influencing Shultz’s views of Soviet bargaining positions on matters ranging from human rights to arms control a decade later. By March 1974, almost nine months after asking to resign, Shultz left the Treasury Department.

Nixon paid a price for his decision. Many years later, in a column published in the New York Times on July 7, 2003, nine years after Nixon’s death, Bill Safire, a former speechwriter for Nixon, wrote that he had contacted Nixon “in purgatory, where he is still being cleansed of his sin of imposing wage and price controls.”32

The political and economic damage caused by the wage and price controls lasted long after Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974. For one thing, the Fed under Arthur Burns increased money growth. This caused inflation to rise and ultimately brought on a recession in 1974–75. President Ford later established a new Council on Wage and Price Stability, which continued to intervene in price and wage setting, and he started a strange policy to reduce inflation.

Despite objections from his chief of staff, Donald Rumsfeld, Ford decided to give a speech before a joint session of Congress and announce a new “Whip Inflation Now” campaign, with a WIN button that people could wear to show that they intended to fight inflation through voluntary pledges to carpool or start a home vegetable garden. Ford simply rejected Rumsfeld’s advice, saying, “Don, I think it is a good program.”

John Taylor and President Ford, January 1977. The White House, courtesy John Taylor.

In the speech, Ford said the pin was a “symbol of this new mobilization, which I am wearing on my lapel. It bears the single word WIN. I think it tells it all. I will call on every American to join in this massive mobilization and stick with it until we do win as a nation and as a people.”33 As Friedman predicted, with the Fed gunning the money supply, inflation remained high, backyard gardens or not, and the new intervention went nowhere.

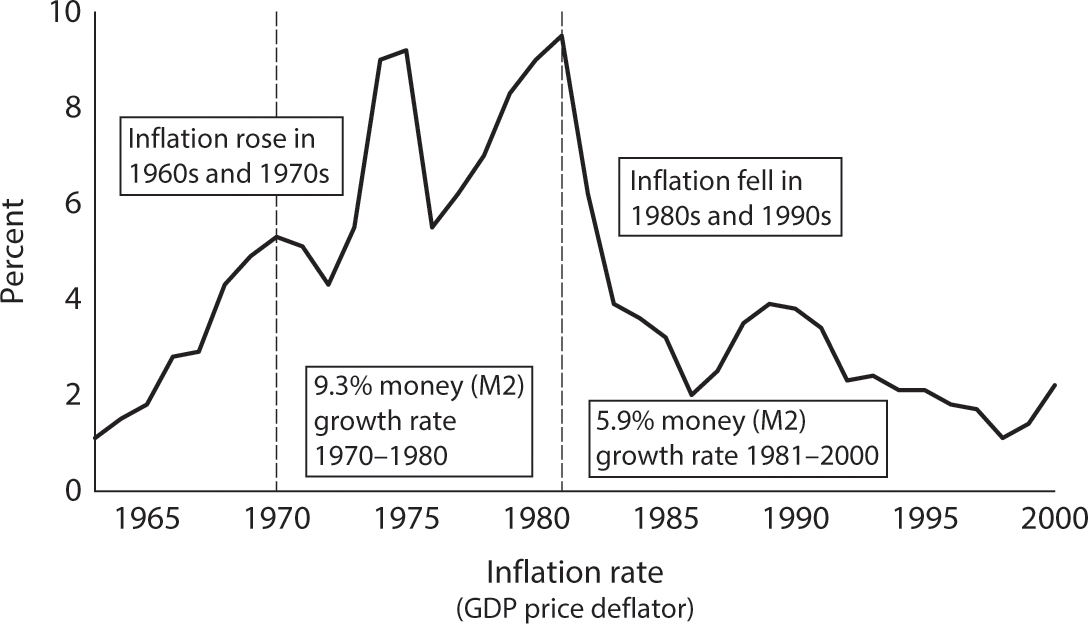

CHART 1. CHANGES IN MONETARY SUPPLY AND INFLATION. Although President Nixon’s New Economic Program wage and price controls, enacted in August 1971, were effective in temporarily suppressing the inflation rate, economic fundamentals such as monetary supply growth, which is influenced by interest-rate decisions, were not reined in. Milton Friedman wrote that Nixon and Fed chairman Arthur Burns had “caught a tiger by its tail.” As soon as those artificial controls were lifted, inflation quickly returned to its previous trajectory. And it resumed its upward march later in the 1970s as monetary supply growth remained loose, with “too many dollars chasing too few goods,” as the saying goes. As the average rate of M2 growth, which measures the supply of money across the economy, gradually declined through the 1980s, inflation fell. Data source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis; US Federal Reserve.

Not all of the president’s economic advisers were pushing these interventionist ideas. John Taylor arrived as a senior economist at the Council of Economic Advisers in the summer of 1976. Alan Greenspan, the chair of the council, was by no means an interventionist in his approach to economics. Indeed, the 1977 Economic Report of the President was quite noninterventionist. It included, for example, the mantra that “tax reform should be permanent rather than in the form of a temporary rebate”34 to emphasize that fiscal policy, as well as monetary policy, should be steady and predictable. But by that time the idea that government just had to “do something,” which was ushered in with wage and price controls, had gained momentum and had spread to other areas of economic policy. The deviation from good, tried-and-true economic policy continued through the 1970s.

CHART 2. AN INFLECTION IN REAL GDP GROWTH. Compare the inflection in the inflation rate in the previous chart with this timeline of the GDP. The abysmal performance of the economy in the 1970s and the restoration of sanity at the start of the 1980s is instructive, as it can tell us something about what works and what does not work. It also shows the need to weather short-term economic fluctuations, which can spoil the politics, in the pursuit of a broader goal. As the next chapter demonstrates, this takes leadership. Data source: US Bureau of Economic Analysis.

NOTES

30. Willard Marriott to secretary of the Treasury George Shultz, January 15, 1973.

31. Secretary of Commerce Frederick Dent to President Richard Nixon, November 2, 1973.

32. William Safire, “Nixon on Bush,” New York Times, July 7, 2003.

33. Gerald Ford, “Address to a Joint Session of Congress on the Economy,” Washington, DC, October 8, 1974.

34. White House, Economic Report of the President, Council of Economic Advisers (1977).