Plant Families |

One of the criteria used in selecting the families to illustrate this book was that they should include common genera in the vegetation of southeastern Australia. In this third edition, more photographs have extended the geographic range, and seen the inclusion of numerous weedy species. Some smaller families, represented by only one or two genera or species, were included because their bright flowers make them visually abundant, for example Hibbertia (Guinea-flower, Fig. 54; Pl. 2d, e). There are also examples where interpretation of floral structure is not immediately obvious, as in Salicornia (Fig. 102), or Euphorbia (Fig. 78; Pl. 18a, b). A few others have interesting features such as insect-trapping leaves or a parasitic habit. The overall aim was to include a broad range of structures.

The sequence of families presented here closely follows the classification scheme of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG) as proposed in 2016 (see Chapter 6). As far as is possible in a linear sequence, related families are placed together. The photographs in the plates follow the same sequence. Families are numbered in Name that flower to assist with finding a particular family in the text; the numbers have no other significance.

For each family, brief notes are provided by way of introductory background. This usually includes an indication of size: very large = more than 10 000 species; large = 5–10 000; rather large = 3–5000; medium-sized = 1–3000; rather small = 500–1000; small = 200–500; very small = less than 200. For most families, the characteristic floral structure is set out in a way that allows ready comparison with other families. This covers the usual variation and may not cope with the possible extremes included in a family. Consulting the illustrations will help to visualise the structure and bring it to life. Inflorescence types expected in a family may be mentioned where they are relatively few or are distinctive. For the remaining families, the discussion concentrates on the illustrated examples.

The ‘spotting characters’ are features, usually readily observed, that are characteristic of a particular group. They may not all be present in all members of a group, but are sufficiently common to be a useful guide, particularly in the field. The breadth of variation in some families is such that spotting characters are few or lacking altogether.

The illustrations and captions should provide enough detail to allow these examples to be used for practice with the keys published in various regional floras (a selection is listed in the references), or with the key here at the end of Chapter 7. This key is designed only for the species illustrated in this book but may work for other species in a genus. The floral formulae used in the captions to convey basic floral details are explained at the end of Chapter 2.

The following list attempts to rank some of the families and genera treated in this chapter in terms of the simplicity of their floral structure. It is intended as a guide to where to start (or where not to start) in approaching plant families.

| Structure straightforward | Structure unusual or complex | |

| 4 Colchicaceae | 6 Orchidaceae | 25 Euphorbiaceae |

| 8 Asphodelaceae | 11 Poaceae | 30 Thymelaeaceae |

| 10 Asparagaceae | 14 Proteaceae | 35 Chenopodiaceae |

| 13 Ranunculaceae | 19 Rhamnaceae | 42 Stylidiaceae |

| 15 Dilleniaceae | 20 Moraceae | 44 Asteraceae |

| 16 Crassulaceae | 21 Casuarinaceae | |

| 23 Tetratheca | ||

| 45 Pittosporaceae | ||

Further information on plant families in general and their characteristics can be found in Christenhusz (2017), Costermans (2009), Heywood et al. (2007), Hickey & King (1997), Judd et al. (2016), Kubitzki (1990–), Lawrence (1951), and Morley & Toelken (1983). The online version of Flora of Victoria (Walsh & Entwisle, 1994–) has been updated to follow the APG classification.

An online key to families is provided by Byng (2014), and in hard copy by Cullen (1997) but in the latter case family circumscriptions may now have changed. Keys and descriptions of families of particular regions are an accepted part of standard floras; for Australian families see the second edition of Flora of Australia volume 1, and on CD-ROM Thiele & Adams (2002).

Keys and descriptions of familes of cultivated plants can be found in Bailey (1949), Cullen et al. (2011), and Spencer (1995–2005). The online version of Spencer has been updated to follow the APG classification.

Families 1 and 2

In earlier classification schemes, the Magnoliids were included within the traditional Dicotyledons. The name Magnoliid is informal in the sense that it has not been formed according to nomenclatural rules—it simply refers to this particular group of four orders and 18 families, and more than 10 500 species.

Plants are mostly trees and shrubs, often aromatic, and usually with simple, rather leathery leaves. Perianth parts are usually arranged in spirals or in whorls of three. An interesting feature of floral structure involves the stamens, which often have a broad connective, and lack a clear demarcation between anthers and filaments (Fig. 22d; Pl. 7e).

1 MAGNOLIACEAE

Magnolias and Tulip Trees

As recognised here, Magnoliaceae is a very small family with a natural distribution in temperate eastern North America south to Brazil, and in eastern Asia from the Himalayas to Japan and south to New Guinea. Up to a dozen genera have at times been recognised in the family, but the number is currently reduced to just two. Liriodendron (with only two species) and Magnolia are both widely cultivated for ornament, and several species are valued for timber.

The family is included with Annonaceae (Pawpaw Family) and Myristicaceae (Nutmeg Family) and several others in the order Magnoliales.

FLORAL STRUCTURE

| Flowers | Actinomorphic, usually bisexual, borne on the ends of branchlets or short lateral shoots. The receptacle is elongated (Pl. 6c), the floral parts mostly spirally arranged. |

| Perianth | Segments often relatively uniform, and may be referred to as tepals (or sometimes all as petals), 6–many, free. |

| Calyx | (When distinguished from petals) sepals 3, free. |

| Corolla | (When distinguished from sepals) petals 3–many, free. |

| Androecium | Stamens numerous, free. The filaments often relatively short and thick, not clearly differentiated from the anthers. |

| Gynoecium | Carpels numerous, free. Ovary superior. Placentation marginal. |

| Fruit | Mostly an aggregate of follicles or these sometimes indehiscent and berry-like (Magnolia), or samaras (Liriodendron, Pl. 6b–d). |

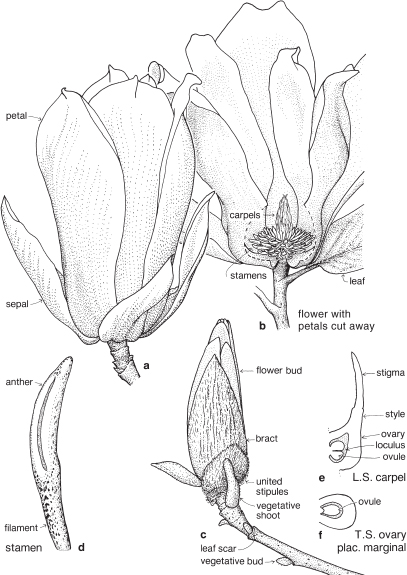

Fig. 22 Magnolia × soulangeana (Magnolia)K3 C5 A∞ G∞

Large shrub or small tree to 4 m or more tall; leaves ovate-oblong, deciduous, with deciduous stipules; flowers terminal; petals variable in number, white inside, and purplish-pink outside. A hybrid, originating in France, now widely grown. Flowering in spring before the new leaves. (a–c ×0.6, d–f ×6)

Plants are usually trees or shrubs, often deciduous, with entire leaves (lobed in Liriodendron) and showy terminal flowers. Large deciduous stipules surround the terminal bud, and leave a scar when shed.

ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 22; Plate 6a–d.

SPOTTING CHARACTERS

Trees or shrubs, often deciduous. Flowers showy, terminal, the parts free and spirally arranged on an elongated receptacle.

2 LAURACEAE

Laurels and allies

Lauraceae are a medium-sized family, widespread and particularly well developed in tropical rainforests. The family name is derived from the genus Laurus (Laurel), and in ancient times the leaves of L. nobilis (Bay Laurel, Pl. 7f–i) were used as the symbol of victory. The aromatic leaves are now used for flavouring soups and meat dishes. Other important cultivated members of the family are Persea americana (Avocado, Pl. 7j–l), Cinnamomum camphora (Camphor Laurel, Pl. 7a–e), and C. zeylanicum, the bark of which yields the spice, cinnamon. Genera growing in northern Australian rainforests include valuable timber trees.

A marked contrast in form is found in the small genus Cassytha (Dodder-laurel, Pl. 6e–i) sometimes placed in a separate family Cassythaceae. It is widespread in tropical and subtropical regions, and all 14 species occur in Australia. Members of the genus are parasitic perennials, with tough twining stems attached to the host plants by small sucker-like pads called haustoria, through which the vascular system of the parasite is linked to that of the host. Leaves are reduced to small scales.

Cassytha glabella (Slender Dodder-laurel) has very fine stems, and is common in heathlands. C. melantha (Coarse Dodder-laurel) and C. pubescens (Downy Dodder-laurel, Pl. 6e–i), both of which have thicker stems, are usually found on trees adjoining heathland and in forests.

FLORAL STRUCTURE

| Flowers | Actinomorphic, usually small, bisexual or unisexual, parts usually in multiples of 3, floral tube sometimes present. |

| Perianth | Sepals and petals not always well differentiated. Tepals often 6 in 2 whorls, free or slightly united. |

| Androecium | Stamens usually in several whorls of 3 (or stamens sometimes numerous), free, staminodes often present, glands often associated with some filaments. Anthers unusual in opening by dehiscence flaps (Pl. 6h, 7e, h, l), these sometimes referred to as valves. |

| Gynoecium | Carpel 1, ovary nearly always superior. Ovule 1, pendulous. |

| Fruit | A one-seeded berry or drupaceous. |

Plants are usually evergreen trees or shrubs. Leaves are usually simple and entire, often rather leathery and with aromatic oil glands (leaves much reduced and scale-like in Cassytha). Stipules are absent.

Flora of Australia volume 2 provides keys and descriptions of Australian species.

ILLUSTRATIONS Plates 6e–i, 7.

SPOTTING CHARACTERS

Excluding the atypical Cassytha, aromatic trees and shrubs, usually evergreen. The flowers, though often small, are distinctive with parts in multiples of three, and anthers with unusual dehiscence.

Monocots (Families 3–11)

There are more than 75 families and more than 70 000 species of Monocots, placed in 11 orders. Most Monocots are herbaceous annuals or perennials that shoot each season from an underground bulb, corm or tuberous rhizome, and many are aquatic or marsh plants. Some, such as the palms and grass-trees, are arborescent. Many species have very short stems, and most leaves are basal, sometimes forming dense tussocks. These leaves are usually long and slender and have parallel venation and a sheathing base. The leaves of species with more developed stems are often sessile with stem-clasping bases (Pl. 10h), and may have parallel or reticulate venation.

The flower parts are frequently in threes, although in some families this is modified by reduction. When the perianth is petaloid there are usually two whorls, each of three parts, which are similar in shape, size and texture, and then often called tepals (e.g. Pls. 8l, 10h, 11e). Such a perianth of undifferentiated parts may be referred to as a perigon. The adoption of the term tepal is not universal however particularly when referring to the orchids. The perianth is much reduced or modified or absent in a number of families such as the grasses and sedges.

Many changes have been proposed with respect to the delimitation of Monocot orders, families and genera during the last several decades and while considerable progress has been made, the situation remains incompletely resolved. Proposals concerning plant classification, with an emphasis on resolving monophyletic groups, have been increasingly influenced by advances in molecular DNA research.

The process of change and refinement is particularly evident with respect to those groups with lily-like flowers (often referred to as ‘petaloid monocots’). These plants, presenting a very broad array of forms which nevertheless display an overall similarity (and continuity) in vegetative and floral structure, have offered little in the way of readily-observed and clear-cut sets of morphological characteristics on which to base family groups.

A traditional grouping, in use for more than 100 years, has seen many Monocot species with lily-like flowers accommodated in three main families: Liliaceae (stamens 6, ovary superior), Amaryllidaceae (stamens 6, ovary inferior) and Iridaceae (stamens 3, ovary inferior). During the twentieth century, while several alternative narrower views were published establishing more families, consensus was not achieved. In contrast, Cronquist’s An integrated system of classification of flowering plants, published in 1981, retained a very conservative approach, with both the traditional Liliaceae and the Amaryllidaceae merged into an enlarged Liliaceae. This concept was adopted in volume 45 of Flora of Australia (1987) and, with reservations, in volume 2 of Flora of Victoria (1994). Conversely, volume 4 of Flora of New South Wales (Harden, 1993), following the classification scheme of Dahlgren and coauthors (1985), incorporated the ‘lilies’ in a number of smaller families.

Thus, depending on when a text was published and what classification scheme the author was following, a particular genus could be found in one of several different families.

The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG) has published four ‘state of play’ classification summaries for the whole of the Flowering Plants between 1998 and 2016, each time incorporating advances in research findings. In the review of 2016 (APG IV), there were about twenty families which included lily-like species.

However, there remains some tension between the pursuit of the scientific ideal of a classification scheme embodying strictly monophyletic groups, and the needs of the wider community of users for a practical and stable set of recognisable families that can be studied and committed to memory, and form the framework for an identification system incorporated in floras. The lack of readily-observed characters by which some of these families can be separated in a key for identification remains an unresolved issue. The online version of Flora of Victoria, to date incorporating the families as proposed by APG IV (2016), has navigated this issue by keying out genera within ‘family complexes’.

In keeping with current treatments, this book treats Liliaceae in a much more restricted sense (i.e. containing fewer genera) than has been the case traditionally, and introduces several other lily-like families as well as retaining a separate Amaryllidaceae. The lack of clear-cut morphological features separating some of these families has meant that ‘spotting characters’ may be sparse or absent. Also included here are an introduction to Iridaceae (Irises), Orchidaceae (Orchids) and Poaceae (Grasses).

Of the five families with ‘lily-like’ flowers dealt with here, Liliaceae and Colchicaceae are representatives of the order Liliales, and Asphodelaceae, Amaryllidaceae and Asparagaceae are placed in the order Asparagales. Members of the Liliales generally have nectaries associated with tepals or filaments (usually towards the base), and some or all of the tepals may be marked, for example with spots or lines of contrasting colour as in Lilium lancifolium (Tiger Lily) and some Fritillaria spp. (Fritillary). In contrast, nectaries of most members of the Asparagales are associated with the ovary, and their tepals are uniformly coloured.

Many lily-like genera produce seeds whose coats contain a black charcoal-like substance called phytomelan (Pl. 11f), a feature which has been given significance in classification in the past. Within the APG IV classification, many members of the order Asparagales produce black seeds, but the correlation of black seeds and particular group(s) is not absolute.

Dahlgren et al. (1985) provide a detailed, informative discussion of the characteristics of Monocot families. For a summary of the history of Monocot classification up to 2002 see Reveal & Pires. Volumes 45 and 46 of Flora of Australia deal with most of the petaloid monocots that are placed here in families 4 Colchicaceae, 5 Liliaceae, 7 Iridaceae, 8 Asphodelaceae, 9 Amaryllidaceae and 10 Asparagaceae (but note that family limits in the flora differ to those given here). Aston (1977) provides a detailed account of aquatic species, illustrated with line drawings.

3 ARACEAE

Arum Lilies, Duckweeds and allies

The Araceae are a medium-sized family, made up of herbaceous species (some very large), mostly tropical in distribution. The inflorescence structure is often somewhat unusual as is the appearance of the whole plant in some cases, for example the free-floating aquatic genera with few or no roots and very reduced flowers such as Lemna and Wolffia (Pl. 8a, b).

A number of species are quite common in temperate gardens, but many are better known as indoor plants, valued for their large, attractive, often hastate to sagittate leaves and the colourful bracts (spathes) associated with the inflorescences. Many are available from nurseries as hybrids or cultivars, and also sold by florists as cut flowers.

Cultivated examples include species of Anthurium, Arisaema (Jack-in-the-pulpit), Arum, Colocasia (Taro), Monstera (Fruit Salad Plant), Spathiphyllum (Spathe Plant) and Zantedeschia (Arum Lily).

Monstera deliciosa (Fruit Salad Plant), a lax scrambler or liane, is well known for its striking, large leaf blades usually with several holes, or splits from the margins in towards the midvein. The edible tubers and leaves of Colocasia esculenta (Taro) are valued throughout the tropics, in some areas forming a staple food crop.

Zantedeschia aethiopica (Arum Lily, Pl. 8c–e), is a tufted herbaceous perennial to about 1.2 m tall with large cordate-hastate leaf blades, commonly grown as an ornamental, and sometimes escaping as a weed. The flowers are unisexual and borne in a yellow-orange spadix, a rather fleshy spike 5–10 cm long, subtended by a large white bract (the spathe). Male flowers are borne in the upper part of the spadix and female below. The male flower consists of a few stamens only, and the female of a small pale gynoecium (Pl. 8e). Perianth parts are absent.

In Arisarum vulgare (Pl. 8f, g) the general inflorescence structure is similar to that of Zantedeschia but the spathe is hooded over the spadix which is extended into a sterile apex protruding from the spathe opening. Male flowers are each reduced to a single stamen.

Wolffia australiana (Pl. 8a, b) is a tiny floating aquatic without roots, capable of forming extensive colonies on still water. It is sometimes found on dams and troughs in farming areas. Flowers are reduced to just a stamen with a unilocular anther, and a unilocular gynoecium embedded in the plant body. However, reproduction is usually vegetative—each plant body (the thallus) ‘buds off’ a daughter—and flowers are apparently seldom produced. The reproductive parts have been interpreted as a single flower or as two unisexual flowers. The genus includes the smallest known flowering plants.

Other members of the family have more fully developed flowers with a perianth and six stamens in two whorls.

Flora of Australia volume 39 provides keys and descriptions of Australian species.

Autumn Crocus, Early Nancy, Milk Maids and allies

Although small, this family of perennial herbs is widely distributed in both hemispheres apart from eastern Asia and South America. They are particularly known from areas with a winter-rainfall Mediterranean climate. Many are cultivated in gardens including Colchicum (Autumn Crocus), Gloriosa (Flame Lily, Pl. 8j, k), and the Australian native genera Schelhammera and Tripladenia (Pl. 8h, i).

Colchicum is important medicinally and is a source of the alkaloid colchicine, used in plant breeding to induce doubling of chromosomes.

A number of genera are highly poisonous, although the tubers of Burchardia (Pl. 8l) and corms of Wurmbea (Fig. 23) were reportedly traditional bush foods of indigenous Australians.

FLORAL STRUCTURE

| Flowers | Usually actinomorphic and bisexual, often borne in terminal racemes or cymes, or umbellate, or solitary in leaf axils. |

| Perianth | Tepals usually 6, free or united, arranged in two whorls of 3, often with glands or a zone of nectar-producing tissue towards the base, the margins often incurved around each stamen in the bud (Pl. 8i). |

| Androecium | Stamens 6, in two whorls of 3, sometimes epitepalous. |

| Gynoecium | Carpels usually 3, united. Ovary superior, usually with 3 loculi, ovules few to many per loculus. Placentation axile. |

| Fruit | Usually a capsule, rarely a berry. Seeds not black. |

Herbaceous aerial parts usually die back each season, regrowing from underground tubers or corms or sometimes tuberous roots. Leaves are usually linear and entire, often arising in basal tufts, but on erect or scrambling stems they are usually alternate and the blades may be broader (in some species ending in a tendril, Pl. 8j).

Native Australian species and weeds are covered in Flora of Australia volume 45.

ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 23; Plate 8h–l.

Plants herbaceous. Leaves often linear and grass-like. Perianth petaloid, in 2 whorls of 3 parts. Stamens 6. In bud each tepal is folded in around a stamen (Pl. 8i). Ovary superior.

female flowers: P3+3 A0 G(3)

male flowers: P3+3 A3+3 G0

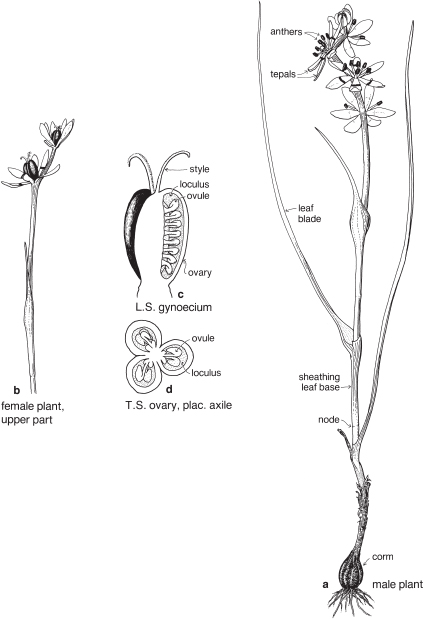

Fig. 23 Wurmbea dioica ssp. dioica (Early Nancy)

Small perennial herb up to about 20 cm high; stem leaves linear with sheathing bases, to 10–12 cm long; flowers white, usually unisexual, 1–8 borne in a terminal spike-like inflorescence; tepals each with a transverse purple band below the centre, the band sometimes identified as a nectary; fruit a capsule. Widespread in grassy places in all states except NT. Flowering in spring. Previously known as Anguillaria dioica. (a–b ×1.5, c–d ×10)

Lilies

The Lily Family, in recent classifications much smaller than in many earlier accounts and treated here in a narrower sense, is widely distributed in temperate regions of the northern hemisphere. The family name is derived from the genus Lilium, which has one species naturalised in Australia (Pl. 9a–e) although many have been introduced and are grown in gardens.

Ornamental genera include Fritillaria (Fritillary), Lilium (Lily), Tricyrtis (Toadlily), and Tulipa (Tulip). The genera Lilium and Tulipa in particular have been the subject of extensive breeding programs; numerous hybrids and cultivars are grown, many highly valued commercially for cut flowers. Bulbs of a number of species are used medicinally, and flowers, leaves and bulbs of various species are edible.

FLORAL STRUCTURE

| Flowers | Actinomorphic, usually bisexual. Inflorescence terminal, often a raceme, sometimes umbellate, or flowers sometimes solitary. |

| Perianth | Tepals nearly always 6, free or united, arranged in two whorls of 3, often marked with spots or lines, often producing nectar towards the base. |

| Androecium | Stamens 6, in two whorls of 3, free, sometimes epitepalous. |

| Gynoecium | Carpels usually 3, united. Ovary superior, usually with 3 loculi. Ovules few to many per loculus. Placentation usually axile. |

| Fruit | Usually a capsule or berry. Seeds not black. |

Plants are perennial herbs with unbranched aerial stems arising from bulbs or rhizomes. The leaves, usually linear and entire, often arise in basal tufts, but on erect stems are alternate and may be narrowly elliptical to ovate.

Australian species and weeds are covered in Flora of Australia volume 45.

ILLUSTRATIONS Plate 9a–e.

SPOTTING CHARACTERS

Plants herbaceous. Leaves often linear and grass-like. Perianth petaloid, in 2 whorls of 3 parts, often marked with spots or lines. Stamens 6. Ovary superior.

Orchids

Orchids form a very large family of about 800 genera, of which about 190 are found in Australia. Although its members are spread all over the world, most of them are in the tropics.

Orchids are important commercially, as they are produced in considerable numbers for the cut-flower trade, and because orchid-growing is such a widespread hobby. The root tubers of a large number of species are known to be traditional bush food, and in Arnhem Land orchid sap has been used as a fixative for ochre pigments. The fruits of species of Vanilla (Vanilla) are the original source of this important culinary flavouring.

FLORAL STRUCTURE

| Flowers | Zygomorphic (rarely more or less actinomorphic), usually bisexual. Flowers solitary, or in racemes, spikes or panicles. |

| Perianth | Parts 6, in 2 whorls, free, or united in various ways. The 3 segments of the outer whorl are called sepals. The 2 lateral segments of the inner whorl are called petals, and in most species the remaining segment is the labellum. |

| Androecium | Stamens usually 1 or 2; 1 in almost all Australian species. |

| Gynoecium | The styles, stigmas and stamen(s) are united into a more or less erect fleshy structure, called the column, in the centre of the flower (Fig. 25). The ovary is inferior and usually unilocular, with 3 parietal placentas. There are numerous ovules (Fig. 26c). |

| Fruit | A capsule, rarely fleshy and indehiscent. |

Most orchids are perennial herbs. They are terrestial, epiphytic or saprophytic and shoot annually from rhizomes, tubers or thickened rootstocks. Some form a pseudobulb, which is the thickened base of an aerial stem. Leaves are simple, entire, and basal or borne on the stem. Stipules are absent.

ILLUSTRATIONS Figures 24–9; Plate 9f–i. Floral formulae have been omitted from the captions. Except for the greenhoods (Figs. 28, 29), in which the perianth parts are variously united, formulae follow the general pattern:

The sepal that sits up at the back of the flower in most species is the dorsal or median sepal and it is often larger than the other two lateral ones (Fig. 26). The modified third petal, the labellum, varies in shape, size and surface characters, and is usually at the front of the flower. It may be simple, toothed, lobed, or fringed with hairs, and the surface can be smooth, papillose, hairy (Fig. 26) or warty (Pl. 9i), or ornamented in numerous ways and colour patterns. Surface or marginal projections are often referred to as calli, and are sometimes glandular, for example secreting pheromones attractive to pollinators (Fig. 24b). A contraction of the tissue at the base of the labellum, if present, is called a claw (Fig. 25). In slipper orchids the labellum is shaped like a small sack.

There are one or two 2-lobed anthers attached near the top of the column. A staminode if present represents a third stamen. Nearly all Australian native orchids have 1 anther. The anther opens by longitudinal slits, and the pollen is often aggregated into groups called pollinia (Fig. 26b). The end of a pollinium is sometimes drawn out to form a sterile stalk, the caudicle.

The stigma, which is borne on the part of the column facing the labellum, is often 2-lobed and there may be a small or conspicuous projection called the rostellum, between the stigma and the anther (Fig. 26b). The column often has lateral outgrowths, which may be in the form of wings as in Caladenia (Spider-orchid, Fig. 25) and Pterostylis (Greenhood, Fig. 28c), or hairy lobes as in Thelymitra (Sun-orchid).

Some common orchids of southern Australia do not entirely fit in with the general pattern outlined above. For example, Thelymitra has a more or less actinomorphic flower with all the sepals and petals about the same size (Pl. 9g), and in Diuris the dorsal sepal is short and broad compared with the other two. In Pterostylis the dorsal sepal is more or less united to the two lateral petals to form a hood or galea (Figs. 28, 29). In a few genera such as Caleana (Duck-orchid, Pl. 9i), and Prasophyllum (Midge-orchid, Leek-orchid, Pl. 9h), the labellum is described as being above the column, which means that, compared with other orchids, the flower is upside down. The column of Diuris is not a single structure, as the anther is borne on a short filament, and the stigma on a separate broad style. Above the stigma is a slot that is said to represent the rostellum. The slot encloses a viscid disc that, at maturity, adheres to the two pollinia from the anther.

Numerous books (and some CDs) have been produced on native orchids—more recent examples include Backhouse (2016), Brown et al. (2008), Brundrett (2014), Hoffman & Brown (1998), Jeanes & Backhouse (2006), Jones (2006), and Jones et al. (2006). An older classic is Nicholls (1969).

SPOTTING CHARACTERS

Plants herbaceous. Flowers zygomorphic, with one petal, the labellum, different from the others, and a central column. Ovary inferior.

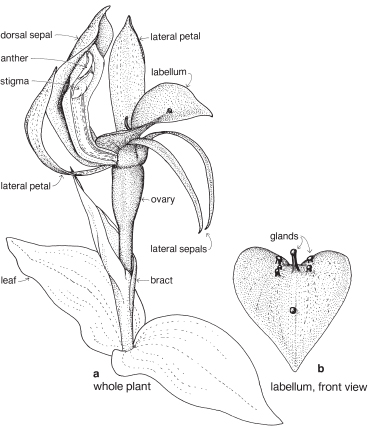

Fig. 24 Chiloglottis valida (Common Bird-orchid)

Small herb to about 5 cm high; basal leaves two, opposite, about 2 cm long and with short stalks; scape bearing one sheathing bract and a solitary flower, bronzy-green or tinted with purplish-brown; the labellum with glandular calli (sometimes referred to as stalked and sessile glands). Widespread in highland forests in Vic. and NSW. Flowering in spring to summer. (a–b ×3)

Fig. 25 Caladenia parva (Green-comb Spider-orchid)

Herb 10–45 cm high; leaf basal, oblong-lanceolate and very hairy; scape erect with one or two sheathing bracts; flower greenish-yellow and maroon, usually solitary, the tips of the sepals thickened and glandular-hairy, the labellum with well-spaced calli, and the column with 2 sessile yellow glands at the base. Widespread, especially on sandy ground in NSW and Vic., probably also SA. Previously included within a broad concept of C. dilatata which has thickened (clubbed) petal tips. Flowering in spring. Cf. Pl. 9f. (×1)

Fig. 26 Calochilus robertsonii (Purplish Beard-orchid, Brown Beards)

Herb to about 40 cm high; leaf solitary, basal, up to 20 cm long, broad at the base and tapering; scape with several leaf-like bracts, and one subtending each flower; flowers green and purple, 2–9 in a loose raceme, the labellum densely bearded. The numerous ovules appear as a dense whitish mass. Widespread in south-eastern Australia. Flowering in spring. (a ×2, b–c ×4)

Fig. 27 Pyrorchis nigricans (Red-beak Orchid)

Herb, 10–30 cm high; leaf basal, broad, ovate to round, thick and fleshy, 1–4 cm wide; flowers pale, strongly streaked with purplish-red, 2–8 in a racemose inflorescence, the flowers and stem turning black as they dry off after fruiting. Widespread on damp and dry heaths. All states except Qld, NT. Flowering infrequent, stimulated by fire, usually spring. Previously known as Lyperanthus nigricans. (×1)

Fig. 28 Pterostylis melagramma (Tall Greenhood)

Herb, 10–30 cm or more high; stem leaves well developed (a basal rosette absent on flowering plants); flowers mostly green, 3–8 borne in a raceme, the lateral sepals bent downwards, the labellum irritable, flicking up into the hood when touched. Widespread in heathlands and forests in southeastern Australia. Previously included with P. longifolia, a species now considered restricted to NSW. Flowering winter to spring. (a ×0.5, b–d ×4)

Fig. 29 Pterostylis nana (Dwarf Greenhood)

Herb, usually less than 15 cm high; leaves in a basal rosette, with short petioles, elliptical, 1–1.5 cm long; flower green, solitary, the lateral sepals held erect. Widespread but never alpine in NSW, Vic., and Tas. A complex of forms which in future may be split up. Flowering winter to spring. (×1)

Irises and allies

A medium-sized, cosmopolitan family especially well represented in South Africa, and Central and South America, although uncommon in lowland areas in the tropics. The type genus Iris is of European origin and is now naturalised in Australia. More than half the species are accommodated in just seven genera: Gladiolus, Iris, Moraea, Romulea, Geissorhiza, Crocus and Sisyrinchium. The curious Tasmanian endemic Isophysis tasmanica is the only member of the family whose flowers have a superior ovary.

The family includes a large number of species with colourful, showy flowers, commonly cultivated for ornament and floristry. Examples of genera include Babiana, Dietes, Crocus, Freesia, Gladiolus, Iris, Ixia, Sparaxis and Watsonia. Many have spread from gardens and become established in south-eastern Australia along roadsides, or in native bushland, and some are seriously invasive in agricultural situations. Commonly naturalised genera include Chasmanthe, Crocosmia (Montbretia), Ixia, Sisyrinchium, Sparaxis and Watsonia. Perhaps the most familiar species introduced in southern Australia is Romulea rosea (Onion Grass), the small, pink, star-shaped flowers very common in lawns and roadsides in springtime. Species of Moraea (formerly Homeria, Cape Tulip) can be troublesome in crops and pastures.

Crocus sativus is the source of the important culinary spice saffron.

Australian native genera include Diplarrena (Butterfly Flag or White Iris), Libertia (Grass-flag, Fig. 30) and Patersonia (Purple-flag).

FLORAL STRUCTURE

| Flowers | Bisexual, often showy, either actinomorphic or zygomorphic, each usually subtended by one or two bracts. Inflorescences various, determinate, usually terminal, often paniculate. In Freesia and Gladiolus (Pl. 10c) the inflorescence is spikelike and the individual flowers are sessile and subtended by 2 bracts. Flowers are sometimes solitary. |

| Perianth | Petaloid, tepals 6 in two whorls of 3, the parts alike or different, often united below into a tube as in Freesia and Gladiolus (Pl. 10c), free or almost so as in Libertia (Fig. 30a), or the outer 3 united at the base to form a tube and the inner 3 erect in the centre as in Iris. |

| Androecium | Stamens usually 3. Commonly free, sometimes joined to the perianth. Anthers often unilateral, (i.e. filaments slightly curved so that the anthers lie on one side of the style, Pl. 10b). The stamens are opposite the carpels—it is assumed that an inner whorl of stamens has been lost during the course of evolution, the presence of which would restore the usual alternation of parts in adjacent whorls. |

| Gynoecium | Carpels 3. Ovary almost always inferior, usually with 3 loculi (Pl. 10e). Style single at the base, then usually dividing into 3 branches, which may be further divided. Ovules few to many. Placentation usually axile. |

| Fruit | A capsule. |

Most members of the family are perennial herbs, sometimes dying back to the rootstock, usually a rhizome, corm or bulb, at the end of each flowering season. Leaves are usually distichous, linear and parallel-veined, with a sheathing base, and may be tufted and cauline. Sometimes the lower few leaves are reduced to sheaths only. Stipules lacking. Flowering stems are commonly upright and bear several leaves which decrease in size towards the inflorescence.

For descriptions and keys to Australian species see Flora of Australia volume 46. Goldblatt & Manning (1998) Gladiolus is one example of quite a number of a detailed texts that concentrate on just one genus.

ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 30; Plate 10a–e.

SPOTTING CHARACTERS

Plants herbaceous. Leaves often linear and somewhat grass-like, and often arranged in two rows, one on each side of, and edge-on to, the axis. (This often results in each tuft of a plant appearing somewhat flattened.) Perianth petaloid, in two whorls of three parts, sometimes zygomorphic. Stamens three. Ovary inferior, of three united carpels.

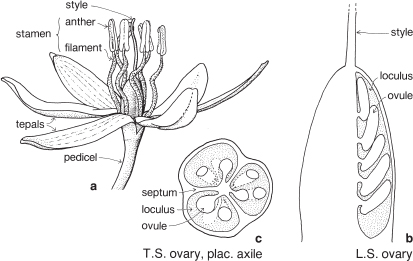

Fig. 30 Libertia pulchella (Pretty Grass-flag)P3+3 A(3) G(3)

Perennial herb; leaves mostly basal, narrow linear, to about 15 cm long; flowering stems to 30 cm tall, the flowers white, on slender pedicels in a few loose clusters, forming a small panicle; fruit a capsule. Found in damp, shaded montane to subalpine forests of Vic., Tas. and NSW. Flowering in spring. (a–b ×7, c ×12)

Asphodels, Daylilies, Flaxlilies and Grass-trees

As treated here, this is a medium-sized family encompassing considerable diversity of form. Except for North America the family is widely distributed, and especially diverse in southern Africa. Numerous genera are grown in gardens including Aloe, Bulbine, Kniphofia (Red Hot Poker, Torchlily), Hemerocallis (Daylily) and Phormium (New Zealand Flaxlily). Some species of Aloe are used medicinally and in cosmetics; Phormium tenax (New Zealand Flax) is the source of a strong fibre.

Native genera are widespread and often common in grasslands, heathlands and light forests. These include Bulbine, Caesia, Chamaescilla (Fig. 32), Dianella (Flaxlily), Stypandra (Blue Lily, Pl. 10h), Thelionema (Fig. 31), Tricoryne and Xanthorrhoea (Grass-tree, Pl. 10i, j). The tufted annual or biennial Asphodelus fistulosus (Onion Weed, Pl. 10f, g) is a common introduced weed of drier parts of southern and eastern Australia particularly in cropping areas on sandy soils.

FLORAL STRUCTURE

| Flowers | Actinomorphic or sometimes zygomorphic, usually bisexual. Inflorescences vary from spikes, or spike-like as in Xanthorrhoea (Grass-tree, Pl. 10i), to paniculate. |

| Perianth | Tepals 6, in 2 whorls of 3, free or united. Usually uniformly coloured. In Xanthorrhoea the outer tepals are papery or scarious, the inner membranous and white or yellowish. |

| Androecium | Stamens 6, in 2 whorls of 3, free or sometimes slightly united at the base, sometimes epitepalous. |

| Gynoecium | Carpels 3, united. Ovary superior with 1–3 loculi. Style single. Placentation usually axile. |

| Fruit | Often a capsule, sometimes a nut or berry. Seeds often black. |

Plant habit varies from climbers as in Geitonoplesium cymosum (Scrambling Lily) to small tufted herbs such as Caesia species (Grass-lily) to substantial tree-like perennials like Xanthorrhoea australis (Austral Grass-tree, Pl. 10i, j) and Aloe arborescens (Octopus Plant). Some species produce rhizomes, many are tufted. Leaves are succulent in genera such as Aloe, Gasteria, Haworthia and several others.

Australian species and weeds are covered in Flora of Australia volume 45.

ILLUSTRATIONS Figures 31, 32; Plate 10f–j.

SPOTTING CHARACTERS

Plants are often tufted herbs with closed leaf sheaths. Inflorescence often terminal on a scape.

Grass-trees may develop a tuft of leaves at ground level, or a simple or branched trunk with a rosette of leaves at the apex. Leaves are tough and linear and often 4-angled. In arborescent plants the older leaves may persist after they die, forming a brownish skirt underneath the rosette. When old leaves finally fall, the resin-impregnated bases remain attached to the trunk forming a protective covering over internal tissues. Flowering of some Xanthorrhoea spp. is stimulated by fire or defoliation.

Grass-trees were very useful to indigenous Australians, who ate the young shoots and soaked the inflorescences in water to yield a sweet drink. Resin from the leaf bases was used as an adhesive, and the stalks of the spikes had some value for spear shafts. In more recent times Xanthorrhoea resin has been used in the production of varnish and dyes.

Fig. 31 Thelionema caespitosum (Tufted Blue-lily)P3+3 A3+3 G(3)

Perennial herb to 60 cm high; leaves in a basal tuft, narrow linear, to 25 cm long; stems leafless, with a few bracts; flowers blue, sometimes yellow or white, in open panicles, the filaments finely hairy; fruit a capsule. Widespread in eastern states in damp coastal heathlands and occasionally further inland. Flowering in spring. Previously known as Stypandra caespitosa. (a ×4, b–c ×12)

Fig. 32 Chamaescilla corymbosa var. corymbosa (Blue Stars, Blue Squill)P3+3 A3+3 G(3)

Perennial herb to 15 cm high; leaves basal, linear, to 8 cm long; flowers blue, up to about 10 borne in a loose corymb. Widespread and common on damp sandy ground, but not in the alps, in all states except Qld and NT. Flowering in spring. (×1.5)

Belladonna Lily, Garlics, Onions and allies

The name of this medium-sized, horticulturally important family is derived from the South African genus Amaryllis (Belladonna Lily, Pl. 11a–c). The family is widely distributed, especially diverse in the Mediterranean, South Africa and South America (particularly the Andes). Three genera are native in Australia: Crinum (Murray Lily), Calostemma (Garland Lily) and Proiphys (Brisbane Lily). Many members of the family are sold as cut flowers, and numerous genera are common in cultivation. These include Agapanthus (Figs. 34, 35), Clivia, Galanthus (Snowdrop), Hippeastrum, Ipheion, Nerine, Amaryllis, Leucojum (Snowflake, Fig. 33), and Narcissus (Daffodil and Jonquil), and the last three are recorded as naturalised in Australia. The genus Allium includes cultivated onions, leeks and garlic as well as A. vineale (Wild Garlic) and A. triquetrum (Three-cornered Garlic), which are significant weeds. White-flowered Nothoscordum borbonicum (Onion Weed) is almost cosmopolitan, and commonly troublesome in gardens.

FLORAL STRUCTURE

| Flowers | Usually actinomorphic, bisexual. Inflorescence usually umbellike, borne on a scape and usually subtended by two bracts (less often one or several, or bracts absent), which may be large and papery (Pl. 11a), each often called a spathe. |

| Perianth | Tepals 6, free or united, arranged in 2 whorls of 3. The corona or trumpet of daffodils and jonquils is usually regarded as an outgrowth from the perianth. |

| Androecium | Stamens usually 6, in 2 whorls of 3, usually free, sometimes united, often epitepalous (Fig. 33b; Pl. 11b). |

| Gynoecium | Carpels 3, united. Ovary often inferior, sometimes superior, with 3 loculi (Figs. 33e, 35c; Pl. 11c). Ovules few to many per loculus. Placentation axile. Septal nectaries may be evident in a transverse section of the ovary (Pl. 11c). |

| Fruit | Usually a capsule, sometimes a berry. |

Most members of the family grow from a perennial bulb, which produces a cluster of basal leaves each season. Others, such as the robust herbaceous perennial Agapanthus grow from a rhizome. Leaves are often linear, and often distichous. In some species, such as Amaryllis belladonna (Belladonna Lily, Pl. 11a) the flowering stem appears before the leaves.

Fig. 33 Leucojum aestivum (Snowflake)

Bulb-forming perennial; leaves basal, linear, up to about 50 cm long; flowers few, nodding, in an umbel-like inflorescence; tepals white, each with a green spot, often regarded as free, but united to a small degree at the base; fruit a capsule. Widely cultivated, origin Europe. Flowering in early spring. (a ×0.25, b ×0.7, c–e ×4)

Australian species and weeds are covered in Flora of Australia volume 45.

ILLUSTRATIONS Figures 33–5; Plate 11a–c.

SPOTTING CHARACTERS

Plants lily-like, with linear leaves often arising from a bulb. Inflorescence on an unbranched stem (scape), umbel-like, often subtended by conspicuous bracts (Pl. 11a).

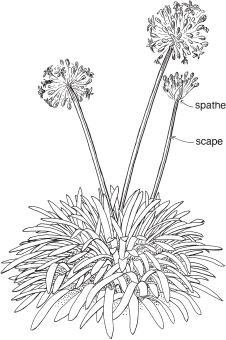

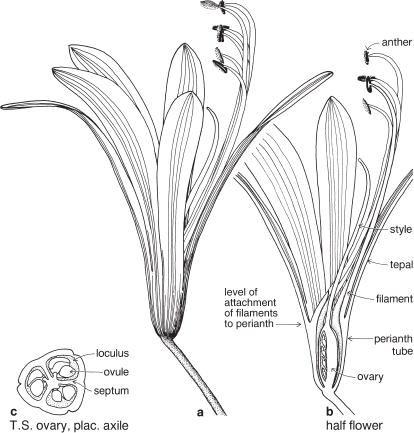

Fig. 34 Agapanthus praecox (Agapanthus) (×0.05)

Fig. 35 Agapanthus praecox (Agapanthus)

Perennial forming large clumps; leaves tufted, distichous, broad-linear, to 40 cm or more long, arising from short thick rhizomes; scape to 60 cm or more tall, bearing an umbel-like inflorescence; flowers blue or white, the tepals united at the base into a perianth tube; fruit a capsule. Widely cultivated, sometimes weedy, origin South Africa. Flowering mainly in summer. (a–b ×2, c ×7)

Asparagus and allies

This is a medium-sized family of wide distribution and great diversity of form. In some previous classifications, species have been accommodated in more than a dozen families. As treated here, the family includes many genera whose members are common in gardens such as Agave, Aspidistra, Chlorophytum, Convallaria (Lily-of-the-valley), Cordyline (Cabbage Tree), Dracaena, Hosta, Hyacinthus (Hyacinth), Liriope (Turf Lily), Muscari (Grape Hyacinth), Ornithogalum, Ruscus, Scilla and Yucca.

Asparagus officinalis provides the young shoots well known as the vegetable asparagus, but this species as well as several others in the genus can become weedy. A. asparagoides (Bridal Creeper) is a seriously invasive weedy climber in south-eastern mainland Australia. Leaves in Asparagus are reduced to small scales which subtend leaf-like cladodes (Pl. 11d).

Common Australian native genera include Arthropodium (Fig. 36), and Lomandra (Matrush, Iron Grass, Pl. 11g–k) the latter mostly hardy, clump-forming perennials now very common in amenity plantings in streets and parks. In commercial plant nurseries these are often lumped in with ‘ornamental grasses’ but differ significantly to true grasses. Leaves are distichous, often rather thick and firm, and the apices often distinctively torn or eroded. The blades tend to merge into the basal sheaths; there is no ligule. Flowers are unisexual (the sexes borne on different plants) with six tepals in two whorls.

FLORAL STRUCTURE

| Flowers | Actinomorphic or zygomorphic, bisexual or unisexual. Inflorescences varied. |

| Perianth | Tepals usually 6, free or united, arranged in 2 whorls of 3. |

| Androecium | Stamens usually 6, in 2 whorls of 3, usually free, sometimes epitepalous, sometimes some reduced to staminodes. |

| Gynoecium | Carpels usually 3. Ovary superior or sometimes inferior. Ovules 1 to many per loculus. Placentation usually axile. Septal nectaries often present. |

| Fruit | A berry or capsule. Seeds often black. |

Species include herbs with bulbs, corms or rhizomes, some climbers, shrubs, thick-stemmed rosette plants, and small, sparingly branched trees. Plants may be small to massive—some species of Agave produce rosettes to 4 m diameter, the inflorescences 8–12 m high. Leaves are often linear and sheathing, but there is much variation. In the small genus Ruscus (Butcher’s Broom, Box Holly) often grown in gardens, leaves are reduced to scales, and the small shrubs produce leaf-like cladodes.

Native species and weeds are covered in Flora of Australia volume 45.

ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 36; Plate 11d–k.

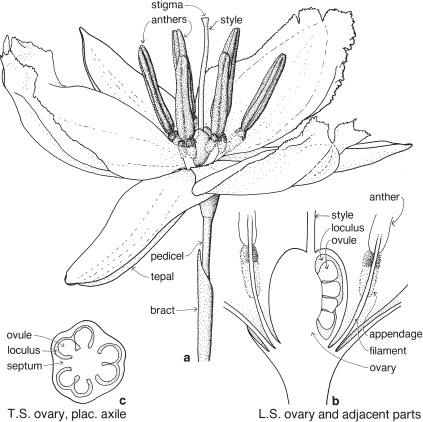

Fig. 36 Arthropodium strictum (Chocolate Lily)P3+3 A3+3 G(3)

Perennial herb to about 1 m high; leaves basal, linear, up to 60 cm long; flowers deep pink to mauve, scented, borne in racemes or loose panicles, one flower at each node; anthers with prominent basal appendages; fruit a capsule. Widespread in heaths, open forests and grasslands in all states. Flowering late spring to early summer. Sometimes known as Dichopogon strictus. (a ×7, b–c ×12)

Grasses

The Grasses form a very large family, although still not as large as the Daisy Family in numbers of genera and species. They are found almost everywhere (even Antarctica), and are estimated to comprise about 20 per cent of the world’s vegetation cover. The family name is derived from the large genus Poa, which includes about 40 species native in Australia, many of which are conspicuous tussock grasses of forests and grasslands. The genus also includes introduced weeds and lawn grasses.

Economically, it is the most important family, not only as a source of food for humans, but also for grazing animals. Many species, such as wheat, barley, maize and rice, have been subjected to breeding and selection in order to improve yield and disease resistance. In a number of countries, bamboo stems and leaves, and the leaves of other large grasses, are used as building materials.

Aboriginal people have traditionally used many native grasses as a food source. They usually ground the seeds to a flour, which they then mixed with water and baked.

There is considerable variation in form within the family, and numerous classification schemes have been proposed. A current scheme recognizes 12 subfamilies, further divided into about 50 tribes. It is emphasised that the notes provided here describe the structure of many common grasses, however the family is large and the breadth of variation considerable. Species will be found that differ in one or more aspects to the general outline given here.

FLORAL STRUCTURE

| Flowers | Small, usually bisexual, sometimes unisexual or sterile, and together with 2 enclosing bracts are usually referred to as florets (Fig. 39; Pl. 13e). |

| Perianth | Either considered absent, or represented by the lodicules, which are small colourless scales, usually 2, sometimes 3, at the base of the ovary (Fig. 39, Pl. 13e). |

| Androecium | Stamens usually 3, rarely 1–6 or more, almost always free. |

| Gynoecium | Ovary with 1 loculus and 1 more or less basal ovule. Carpel number a matter of debate. Styles and stigmas usually 2, sometimes 3. |

| Fruit | Usually a caryopsis. |

Grasses are perennial or annual herbs, sometimes tree-like (bamboos), sometimes forming tussocks, or with rhizomes or stolons. The root system is fibrous, and large grasses such as bamboo or maize often produce adventitious roots, or prop roots, from the lower stem nodes. The stems of most grasses, usually called culms, terminate in an inflorescence.

The leaf usually has a basal sheath, commonly open down one side, which is wrapped around the stem. The leaf blade is most often linear, often flat, but may be folded or rolled, and has parallel venation. At the junction of the sheath and blade there is nearly always a line of hairs or a membranous flap of tissue called a ligule (Fig. 38b).

FURTHER NOTES ON THE FLOWERS AND INFLORESCENCES

The small flower together with its two subtending bracts is usually called a floret (Fig. 39; Pl. 13e). The outer or lower bract is the lemma or flowering glume, and this partially encloses the upper bract, the palea. Between the lemma and palea are the ovary and stamens. The tiny lodicules are at the base of the ovary next to the lemma, and at anthesis become swollen, pushing the lemma and palea apart and allowing the stamens and stigmas to protrude (Pl. 13e). Florets are commonly bisexual but may be sterile, male or (rarely) female. Sterile florets, also called barren or neuter florets, may be reduced to a lemma only. Rudimentary florets, where the bracts (lemma and palea) are reduced in size, sometimes to stubs of tissue, are not uncommon.

The florets are arranged in spikelets (Fig. 38d; Pl. 13). The spikelet is made up of one or more sessile florets on an axis, the rachilla, and at the base are two further bracts, the upper and lower glumes. Sometimes one of these glumes is reduced in size; rarely one is absent. In spikelets with numerous florets, the uppermost one or few may be rudimentary.

The spikelet is considered as the basic unit of grass inflorescences. Like flowers of other families, spikelets may be pedicillate or sessile, and arranged in spikes, racemes, panicles or more complex inflorescences (Figs. 38c, 40b, 41a; Pl. 13h).

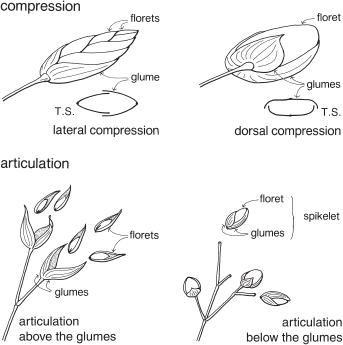

The term compression describes the way in which the spikelets are flattened (Fig. 37; Pl. 13a, i). Compression is lateral if the spikelet lies readily on its side, and dorsal if the spikelet is flattened back and front. Occasionally spikelets show no particular compression.

At maturity the spikelet may break up, with the florets falling separately, or it may fall as a unit. When the glumes remain on the plant, the articulation is said to be ‘above the glumes’. When they fall with the spikelet, articulation is ‘below the glumes’ (Fig. 37). This can often be seen before the fruiting stage by gently pulling the florets and noting the point of breakage.

Stiff, bristle-like appendages, called awns, are quite common, particularly on the lemmas.

The common terms ‘grain’ and ‘husks’ are not always used consistently. Typically the husks are the lemma and palea, and the grain is the fruit.

Useful references dealing with grasses include Barkworth et al. (2007), Clarke (2015), Champion et al. (2012), Cope & Gray (2009), Gibbs Russell et al. (1990), Hubbard (1984), Jessop et al. (2006), Lazarides (1970), Morris (1991), Sharp & Simon (2002), Simon & Alfonso (accessed 2018), and Wheeler et al. (2008).

Fig. 37 Grasses—compression and articulation

Grass spikelets usually readily lie on their sides or backs: lateral or dorsal compression. In most species, at maturity, the glumes either fall with the spikelet, or they remain attached to the plant: articulation below or above the glumes.

flower + lemma + palea = floret

one or more florets + glumes (upper + lower) = spikelet

spikelet = the basic unit of grass inflorescences, arranged in spikes, racemes, panicles, etc.

ILLUSTRATIONS Figures 38–41; Plate 13.

SPOTTING CHARACTERS

Plants herbaceous, culms usually terete, usually with hollow internodes. Ligule usually present, leaf sheath often open. Florets with two bracts (lemma and palea). Spikelets usually with two bracts (upper and lower glumes).

INTRODUCTION TO SOME GRASS-LIKE FAMILIES

The common perception of which plants are grasses is often broad. This is no doubt influenced to some degree by the horticulture and landscaping industries regularly including within the category ‘ornamental grasses’ any more or less tufted herbaceous species that do not produce particularly showy flowers. Stems are often green, and the plants may or may not have elongated strap-shaped leaves. These species may belong to one of several other families, some of which are introduced here.

Clarke (2015) includes a detailed introduction to the following families, and Sharpe (1986) provides keys to Queensland representatives. Champion (2012) introduces common New Zealand sedges and rushes.

Family Cyperaceae (Sedges, Pl. 12a–i)

Sedges form a large family with world-wide distribution. Superficially, many Sedges and Grasses are quite similar in their tufted habit, and elongated linear leaf blades with a sheathing base. In the Sedges, the leaf sheath is usually closed, and a ligule often absent. Culms are often solid, and flattened or triangular in cross-section. The inflorescence is often subtended by obvious bracts. As in the Grasses, Sedge flowers are in most cases arranged in spikelets (although these are not considered strictly equivalent botanically to spikelets of Grasses). Within the spikelets each flower is enclosed by only one bract. A perianth is either absent or represented by, for example, scales, hairs or bristles.

Family Juncaceae (Rushes, Pl. 12j–l)

This is a relatively small family, mostly known through two genera: Juncus (Rush) with several hundred species and a world-wide distribution often in damp or aquatic habitats, and Luzula (Woodrush) with a little over a hundred species in the northern hemisphere, South America and Australasia. Variation in general appearance is considerable, from small tufts a few centimetres high to expansive stands of stems several metres tall. Rhizomic species with stems arising at intervals are quite common. Rushes may also be densely tufted with numerous upright, slender, cylindrical and apparently leafless stems; species with this form are sometimes planted on pond margins, or grown for restoration of aquatic habitats. The flowers of Rushes, although small, show the typical monocot pattern of floral parts in threes. Their flowers are quite lily-like in structure, although usually not at all showy — their tepals are often brown or straw-coloured, and may be only a few millimetres long. Carpels are united, usually three in number, and the fruit is a small capsule. Woodrushes have just three seeds per capsule while in Juncus seeds are tiny and numerous.

Family Restionaceae (Restios, Rope-rushes and Cord-rushes)

This small family is almost entirely restricted to the southern hemisphere, with greatest representation in South Africa and Australia. Species are becoming more common in gardens coinciding with the rise in demand for plants of attractive clumping form that are economical in their use of water. Others are well suited to aquatic habitats. Leaves are reduced to sheaths, open down one side, and not developing more than a rudimentary blade. A ligule is not produced. The sheaths are often a different colour to the stems giving the plant a banded appearance. Flowers are almost always unisexual, and in most cases are borne in separate inflorescences on separate plants. The male and female inflorescences of the same species can appear quite different, sometimes a challenge when an unknown species is encountered in its natural habitat. Flowers are mostly borne in spikelets, each usually with a small, often brownish perianth, and subtended by a brownish bract. The fruit is usually either a small nut or a capsule.

Australian members of the family are covered in Australian Rushes by Meney & Pate (1999). Haaksma & Linder (2000) provide a guide to South African species, some of which are seen in cultivation.

Fig. 38 Bromus catharticus (Prairie Grass)

Annual or biennial, 40–100 cm high; leaves rough on the upper side, the sheaths often softly hairy; ligule membranous; spikelets 6- to 8-flowered, pale green, in a loose panicle; compression lateral; articulation above the glumes. Widespread in Australia, a common weed or pasture grass, introduced from Sout America. Flowering spring to early summer or longer if conditions suitable. Previously known as B. unioloides. See also Pl. 13a, b. (a ×0.2, b ×1.5, c ×0.6, d ×2.5, e ×4)

Fig. 39 Lolium perenne (Perennial Ryegrass)

Biennial or short-lived perennial up to c. 50 cm high; leaves narrow-linear, mainly basal; leaf blades auriculate (auricles sometimes small or eroded); ligule membranous; spikelets about 8- to 10-flowered, solitary and sessile in alternate notches of the rachis, forming a slender spike; topmost spikelet with two glumes, all others with only one; compression lateral; articulation above the glumes. Native to Europe, N Africa, and Asia, now naturalised in Australia, and a common and valuable pasture or lawn grass. Plants are often found with short awns on some of the lemmas. These are usually regarded as hybrids, many of which have been developed for agricultural purposes. Flowering in summer. See also Pl. 13c. (×13)

Fig. 40 Lolium perenne (Perennial Ryegrass) (a ×0.5, b ×1, c ×6)

Fig. 41 Cynodon dactylon (Couch Grass)

Variable, rhizomic and stoloniferous perennial, often long-creeping; ligule a ring of hairs; spikelets purplish-green, 1-flowered, sessile, in two rows on one side of an axis forming a slender spike; 2–6 of these spikes arranged digitately at the top of the culm; compression lateral; articulation above the glumes. Widespread in Australia, common as a weed or lawn grass. Flowering in summer. See also Pl. 13d, e. (a ×0.6, b ×12)

Eudicots (Families 12–46)

The APG classifications have seen the separation of several groups, such as the Magnoliids, from the former Dicotyledons (see Chapter 6). The remaining 312 families are now often informally referred to collectively as the Eudicotyledons (for convenience abbreviated to Eudicots). Their flowers are usually made up of whorls of four or five parts, and anthers are well differentiated from slender filaments (cf. the Magnoliids).

12 PAPAVERACEAE

Poppies and Fumitories

Papaveraceae is a relatively small family, although well known through a number of popular ornamentals such as Papaver nudicaule (Iceland Poppy, Pl. 4f, g), Corydalis, Dicentra (Bleeding Heart) and Eschscholzia californica (Californian Poppy). The latter has a habit of escaping from cultivation. Economically the most important species is Papaver somniferum (Opium Poppy), the capsules of which yield alkaloids used medicinally. The seeds of several other species provide useful oils.

Mostly found in temperate parts of the northern hemisphere (only a few extending to southern Africa), nearly all members of the family are herbaceous annuals or perennials. The family is currently divided into several subfamilies all of which have at times been treated at family rank. One of these subfamilies, Fumarioideae, is mostly known for the common weedy annual genus Fumaria (Fumitory) well naturalised in south-east and south-west Australia.

FLORAL STRUCTURE

Most members of the family are herbaceous, often with milky sap, some are soft-wooded shrubs. Leaves are often deeply lobed or dissected (Pl. 4a), or pinnately to ternately divided. Stipules are absent.

Flora of Australia volume 2 includes keys and descriptions to Australian species. Murphy (2009) is a very useful text for identifying Fumitories.

ILLUSTRATIONS Plate 4a–g.

SPOTTING CHARACTERS

Plants herbaceous, leaves often dissected or much-divided, stipules absent. Flowers regular and showy or markedly zygomorphic, sepals usually 2.

Buttercups and allies

This medium-sized family is found world-wide although mainly in the temperate zones, and it is most diverse in the northern hemisphere. The name of the type genus Ranunculus (Buttercup, Pl. 2a–c) comes from a Latin word meaning a little frog or tadpole and, as it might suggest, many buttercups are marsh plants. There are several large genera such as Aconitum (Monkshood), Delphinium (Larkspur) and Ranunculus but, at the other extreme, about one-third of the genera contain only one species.

Many genera are seen in gardens including species of Aconitum, Anemone (Windflower), Aquilegia (Columbine), Caltha (Marsh Marigold), Clematis, Delphinium, Helleborus (Hellebore), Ranunculus and Thalictrum (Meadow Rue). Quite a number of species are poisonous.

FLORAL STRUCTURE

| Flowers | Usually actinomorphic, sometimes zygomorphic, usually bisexual (sometimes unisexual as in Clematis, Fig. 42). |

| Perianth | Tepals 4–numerous, free, petaloid (as in Clematis, Fig. 42a, c); or perianth composed of calyx and corolla. |

| Calyx | Sepals usually 5, free. |

| Corolla | Petals usually 5, sometimes more, free, often with nectar-producing tissue or gland towards the base. |

| Androecium | Stamens several to numerous, free (Fig. 42a; Pl. 2a). Staminodes sometimes present. |

| Gynoecium | Carpels usually numerous, free, and spirally arranged on the receptacle, rarely few, rarely united. Ovary superior. Ovules one to many per carpel, placentation marginal. |

| Fruit | Usually an aggregate of small achenes or follicles (Pl. 2b), occasionally berries. |

Plants are usually perennial herbs, sometimes annual, or shrubs or sometimes climbers as in Clematis. Leaves diverse in shape and degree of division. Stipules usually absent.

Flora of Australia volume 2 includes keys, and descriptions of Australian species.

ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 42; Plate 2a–c.

SPOTTING CHARACTERS

Plants often herbaceous. Flower reproductive parts often numerous, free and spirally arranged.

male flower: K4 C0 A ∞ G0

female: K4 C0 A staminodes G ∞ plac. apical

Fig. 42 Clematis microphylla (Small-leaved Clematis)

Slender-stemmed climber to c. 5 m high, with opposite, divided leaves, the petioles often twining; flowers unisexual, without petals, borne in small axillary or terminal panicles; female flowers with 4 staminodes; fruit a cluster of achenes, the hairy style becoming a plumose beak on each achene and assisting with dispersal. Common in temperate parts of Australia. Flowering in winter and early spring. (a ×3, b ×12, c ×3, d–f ×7)

Proteas, Banksias, Grevilleas and allies

Most of the genera in this medium-sized family are found in the southern hemisphere. More than half the genera occur in Australia and the remainder are mainly South African or South American. In spite of superficial morphological similarities, the Australian and South African genera are not closely related and none is common to both regions. The family is a very old one and the distribution patterns are thought to have existed before the separation of the southern land masses. There is great diversity of form within the Proteaceae, but its floral structure is distinctive. The family name is derived from the South African genus Protea, often grown in Australia as an ornamental.

Many species of Banksia, Hakea and Grevillea produce abundant nectar, which was utilised by indigenous Australians. The flowers can be sucked or soaked in water to produce a sweet drink. Timber from two rainforest trees, Grevillea robusta (Silky Oak, Figs. 48, 49) and Cardwellia sublimis, is used for furniture. Two species of Macadamia produce the commercially available macadamia nuts, and Telopea (Waratah), Banksia and Protea are cultivated for the cut-flower trade. Many members of the family are planted as ornamentals, including the genera Hakea, Grevillea, Banksia, Telopea, and Stenocarpus (Firewheel Tree) from Australia and Protea, Leucodendron and Leucospermum from South Africa. Grevilleas hybridise readily and the many cultivars available are planted extensively in parks and gardens.

FLORAL STRUCTURE

| Flowers | Either actinomorphic or zygomorphic. Usually bisexual, occasionally unisexual. Inflorescences complex, often racemose, cone-like, spike-like or in dense heads. Flowers occasionally solitary and axillary (e.g. Persoonia, Fig. 51). |

| Perianth | Tepals 4, petaloid, free or united. In bud the tepals are valvate and more or less united, at anthesis they either roll back and become free, or remain united at the base. |

| Androecium | Stamens 4, sometimes 3, usually epitepalous. Filaments are often very short, so the anthers appear to be joined directly to the tepals (Figs. 50c, 53a; Pl. 3a). In some genera, as in Conospermum (Smoke-bush), 1 anther lobe or 1 or more anthers may be sterile (Fig. 47c, d). |

| Gynoecium | Carpel 1, ovary superior, stalked or sessile. Ovules 1–many. Style-end often conical or discoid. Hypogynous glands usually present, but variable in shape and number, reduced to one in Grevillea and Hakea (Figs. 45d, 49b, 50c; Pl. 3a). In many genera, before the flower opens, the pollen is shed onto the style-end, sometimes called the pollen-presenter (Fig. 50b; Pl. 3a, b). The stigmatic area, in the middle of the pollen-presenter, becomes receptive some time after anthesis, and when the pollen from that flower has dispersed. |

| Fruit | Either a woody or leathery follicle, or a drupe (Persoonia) or small and nut-like (Conospermum, Isopogon). |

Members of the family are shrubs or trees. Leaves are mostly simple but often lobed or deeply divided, and usually stiff and leathery. Many genera have tough, terete, pungent leaves. There are no stipules. Young leaves and branches are often bronze in colour due to the presence of T-shaped hairs, which are usually shed as the part matures.

For descriptions and keys to Australian species see Flora of Australia volumes 16, 17A, 17B. Books dealing with various genera include Blomberry & Maloney (1992), Collins et al. (2008), George (1996), McGillivray (1993), Olde & Marriott (1994–5) and Wrigley (1989).

ILLUSTRATIONS Figures 43–53; Plate 3a, b.

SPOTTING CHARACTERS

Perianth single, 4-partite, often characteristically zygomorphic, with 4 epitepalous stamens. Habit woody, leaves leathery, often terete and pungent. Fruit often a woody or leathery follicle.

Fig. 43 Adenanthos terminalis (Gland Flower)

Spreading shrub to 1 m high; branches slender, erect, the young branches and leaves pubescent; leaves crowded and overlapping, 0.5–2 cm long, digitately divided into 3–5 terete lobes; flowers pale yellow, terminal, sessile and 1–3 per cluster; four small nectary glands surround the ovary and alternate with the tepals; fruit a pubescent nut. Uncommon in sandy heaths of western Vic., southeastern SA and Kangaroo Is. Flowering in spring. (a–c ×3; d ×10)

Fig. 44 Banksia marginata (Silver Banksia)

Habit variable, low stunted shrub or small tree; young shoots bronze in colour due to T-shaped hairs; leaves shortly stalked, leathery, 2–8 cm long with truncate apices, the margins sometimes shortly toothed, the underside white-tomentose, and the veins conspicuous; flowers small, cream to yellow in a terminal spike-like inflorescence 4–10 cm long; four small nectary glands alternate with the tepals at the base of the ovary; fruit a follicle. Widespread in Vic., SA, Tas., and NSW. Flowering in autumn to early spring. (a–b ×0.7)

Fig. 45 Banksia marginata (Silver Banksia)

a two flower buds with subtending bracts; b flower bud at anthesis, side view; c flower, side view; d base of perianth , internal view; e ovary and base of style, side view; f as in (e) but L.S.; g T.S. ovary, placentation marginal (a–c ×5, d–g ×10)

Fig. 46 Conospermum mitchellii (Victorian Smokebush)

Upright, often multi-stemmed shrub 1–2 m tall; leaves linear, 5–15 cm long; inflorescence a corymbose panicle; flower buds bluish-grey, the flowers white, each subtended by a dark bract; lobes of adjacent anthers at first united, and only 4 of the 8 lobes are fertile; the other 4 lobes are reduced to small appendages; front stamen with 2 functional lobes, the 2 lateral stamens with one functional lobe each; fruit a pubescent nut. In Vic. on sandy heaths at Anglesea and in the south-west, and possibly south-eastern SA. Flowering in spring. There are more than 40 species of Conospermum in WA, about 10 in eastern states. (×0.7)

Fig. 47 Conospermum mitchellii (Victorian Smokebush)

a flower and bract, side view; b half flower; c stamens and style, from above; d stamens dehisced, from above; e T.S. ovary, placentation apical. (a–e ×12)

Fig. 48 Grevillea robusta (Silky Oak)(a ×0.3, b ×0.7)

Fig. 49 Grevillea robusta (Silky Oak)

Tall forest tree to 30 m; leaves pinnate, divided into 10–25 leaflets which are further divided or lobed; flowers orange, borne in one-sided racemes; ovary with a short stalk. Occurs in rainforests and along creeks in Qld and northern NSW, and extensively grown in southern Australia in parks, gardens and as a street tree. In Vic., flowering in early summer. (a–b ×3, c ×12)

Fig. 50 Grevillea rosmarinifolia (Rosemary Grevillea)

Spreading shrub to about 2 m high; leaves linear, sharp-pointed, 2–4 cm long, often with recurved margins; flowers red, pink or cream, often red and cream, in short racemes, the perianth glabrous externally; fruit a follicle, the style persistent. Widespread but scattered, mostly on dry, rocky sites in Vic., and NSW. Extensively grown for ornament in gardens and roadside planting. Peak flowering time early spring. See also Pl. 3a. (a ×1.2, b, c ×3, d × 12)

Fig. 51 Persoonia juniperina (Prickly Geebung)

Bushy shrub, usually about 1 m high; leaves linear, sessile, sharp-pointed, c. 3 cm long, channelled on the upper surface; flowers with short stalks, axillary, solitary, yellow; ovary with a short stalk and with small nectary glands at the base; fruit a drupe, blue-black at maturity. Widespread in heathlands and drier forests of Vic., NSW, Tas., and SA, especially near the coast. Flowering in summer. (a–c ×9)

Fig. 52 Hakea decurrens (Bushy Needlewood)

Variable bushy shrub; leaves terete, pungent, about 2–6 cm long, grooved below at the base; flowers small, white or sometimes pink, in axillary clusters of 4–6; fruit woody, about 2–4 cm long, sometimes almost spherical, a beak at the apex of each valve, the surface rough. Widespread and locally common in drier forests especially those with a heathy understorey in Vic., NSW and some Bass Strait islands. Flowering in winter to spring. (×0.7)

Fig. 53 Hakea decurrens (Bushy Needlewood)

a flower cluster in the axil of a leaf—the lowest flower is shown in section; b T.S. ovary, placentation marginal. (a ×8, b ×25)

Guineaflowers

This small family of trees, shrubs and climbers is almost entirely tropical. The type genus, Dillenia, is found in northern Australia and extends to South-east Asia. Three other genera occur in Australia of which Hibbertia is by far the largest.

In southern Australia, particularly WA, Hibbertia (Guinea-flower) is widespread, and the bright yellow flowers that are characteristic of the family make them conspicuous components of heathlands and forests.

Although it would seem they have much to offer in terms of ornamental value, relatively few are well known in gardens. One of the most popular species is Hibbertia scandens (Climbing Guinea-flower) a scrambler or climber native to coastal eastern Australia and adjacent hinterland, with bright yellow flowers up to 7 cm diameter.

Flowers of Hibbertia (Guinea-flower, Fig. 54; Pl. 2d, e) are usually regular and bisexual. There are 5 persistent sepals. The 5 petals are often crumpled in bud, the apex often notched, and they may fall soon after anthesis. Stamens are few to numerous, free or partly united at the base, and some may be reduced to staminodes. They either surround the carpels or form a single group to one side (Fig. 54a). The 2–3 carpels are free, often with curved styles, and contain 1–many ovules. The fruit is a cluster of follicles.

The type and distribution of hairs on the plants are important features in identification. Stellate hairs are common. A number of papers by Toelken examining various groups of species, and describing new ones, have appeared in the Journal of the Adelaide Botanic Gardens from 1995 onwards (e.g. see Toelken (2013) in the references).

Fig. 54 Hibbertia ripariaK5 C5 A6 G2

Erect shrub to about 50 cm tall; leaves linear-oblong, to 8 mm long, often with stellate hairs, margins revolute, apex obtuse; sepal inner surfaces shiny, the outer surfaces with stellate hairs; fruit a pair of follicles. A variable species widespread in southern and eastern Australia; this variant occurs in southern Vic. and is also recorded in SA. Flowering in spring. See also Pl. 2d, e. (a ×7, b ×25) Hibbertia riparia is currently considered to represent a ‘species complex’. It is likely that Victorian plants will receive a different name when a review of the complex is completed.

18 Family EUPHORBIACEAE

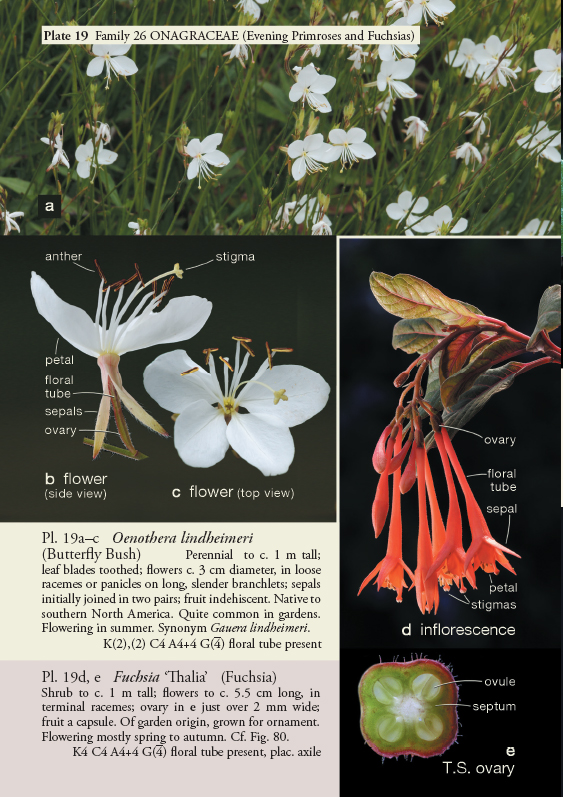

19 Family ONAGRACEAE

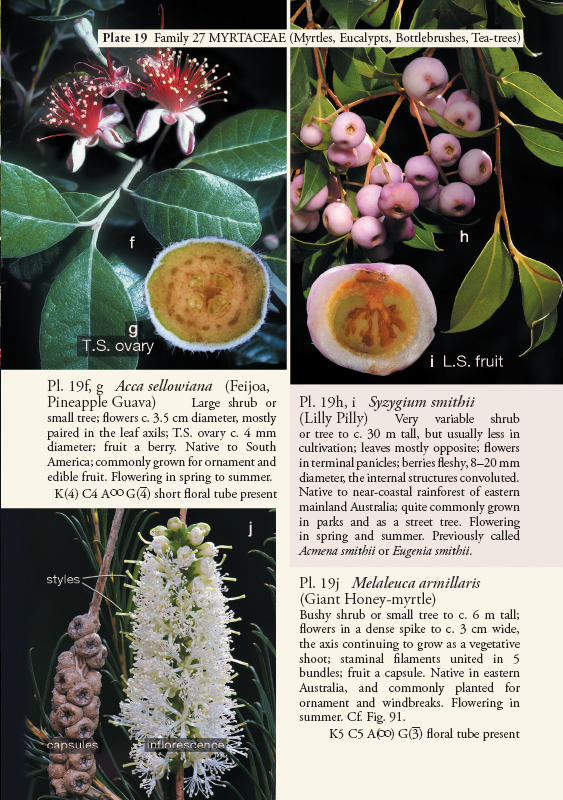

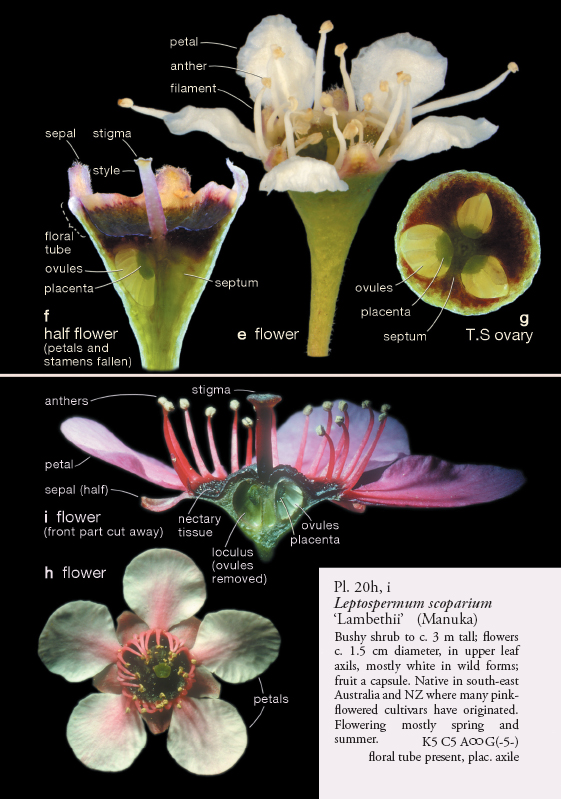

Family MYRTACEAE

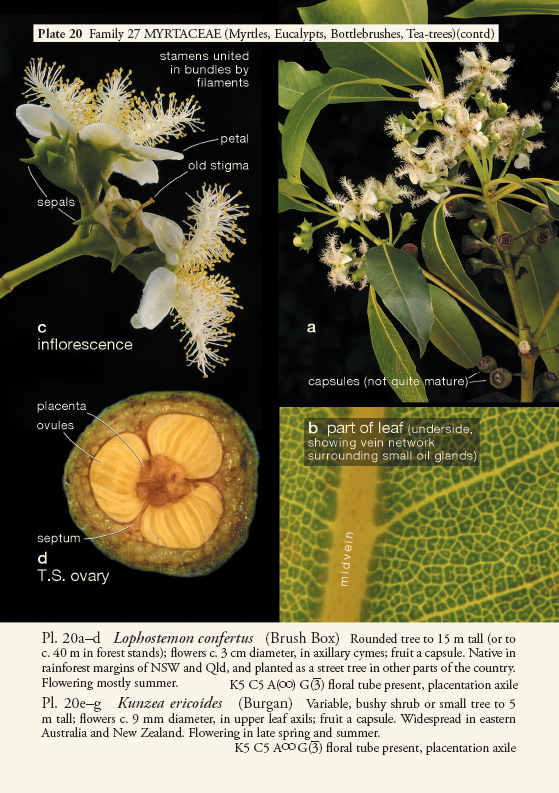

20 Family MYRTACEAE

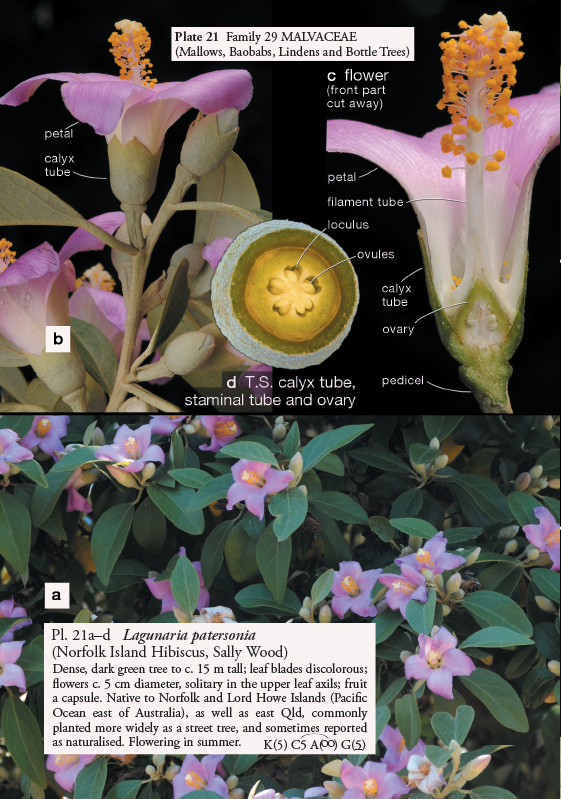

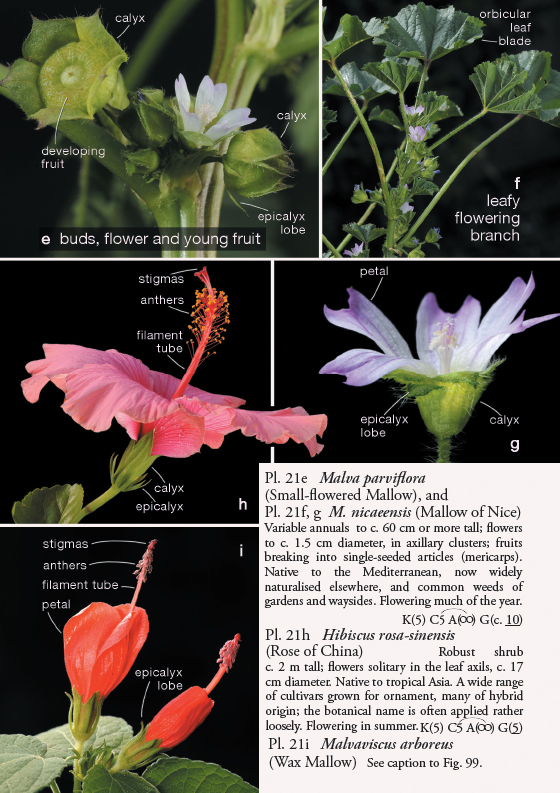

21 Family MALVACEAE

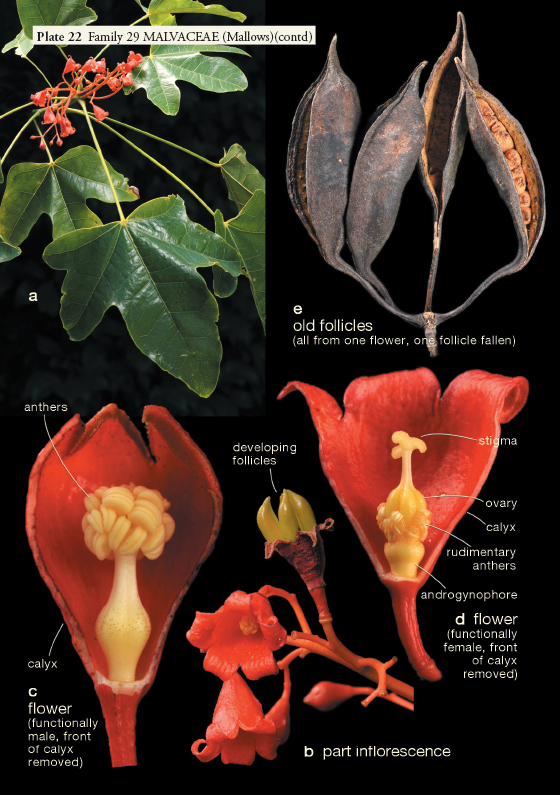

22 Family MALVACEAE

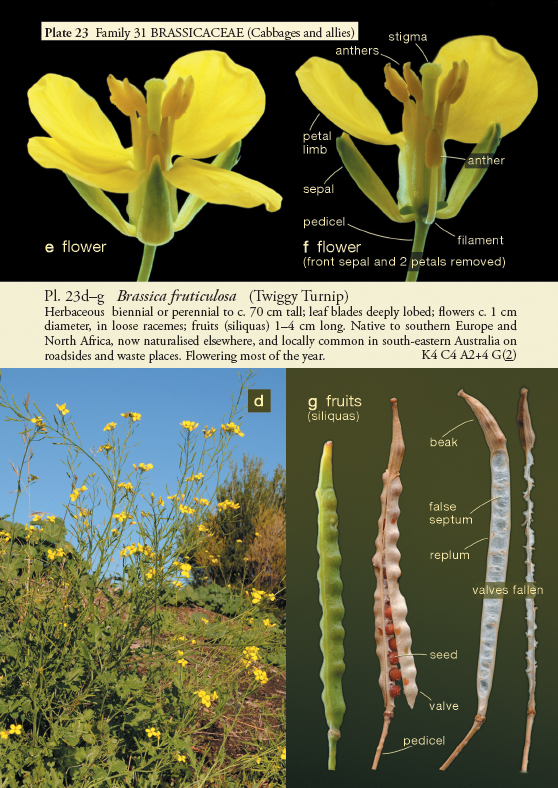

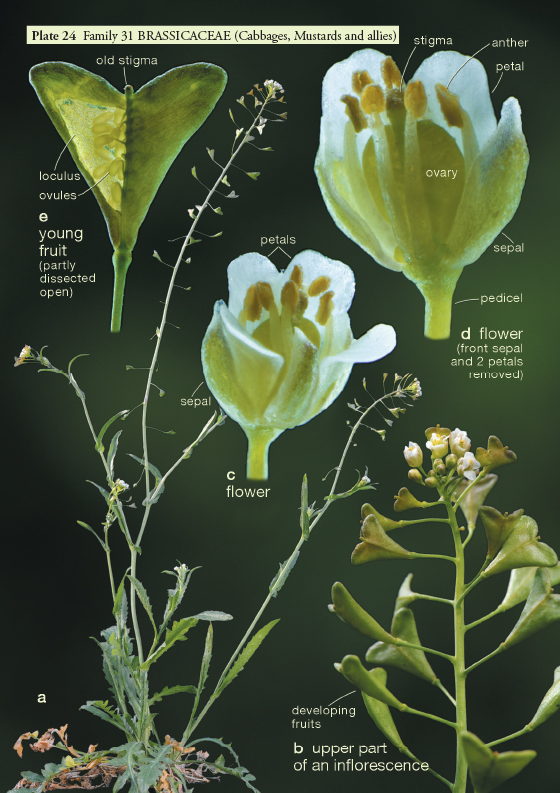

23 Family BRASSICACEAE

24 Family BRASSICACEAE

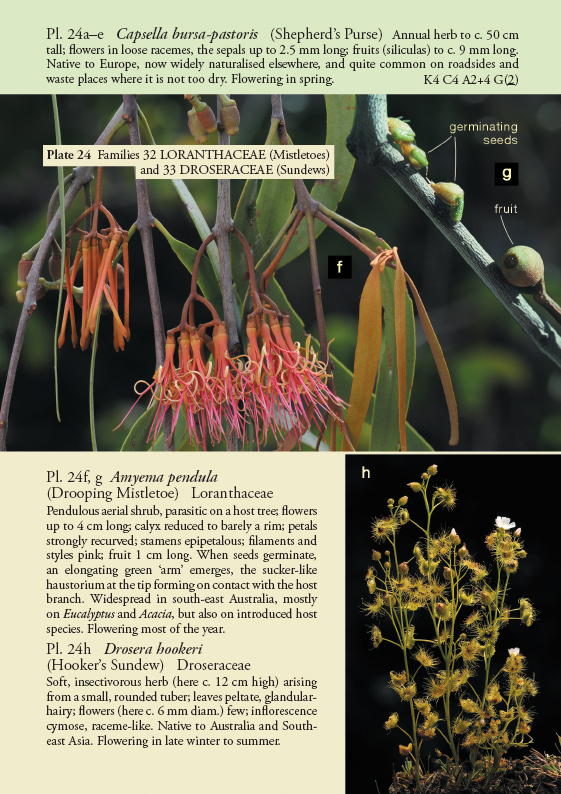

Family LORANTHACEAE

Family DROSERACEAE

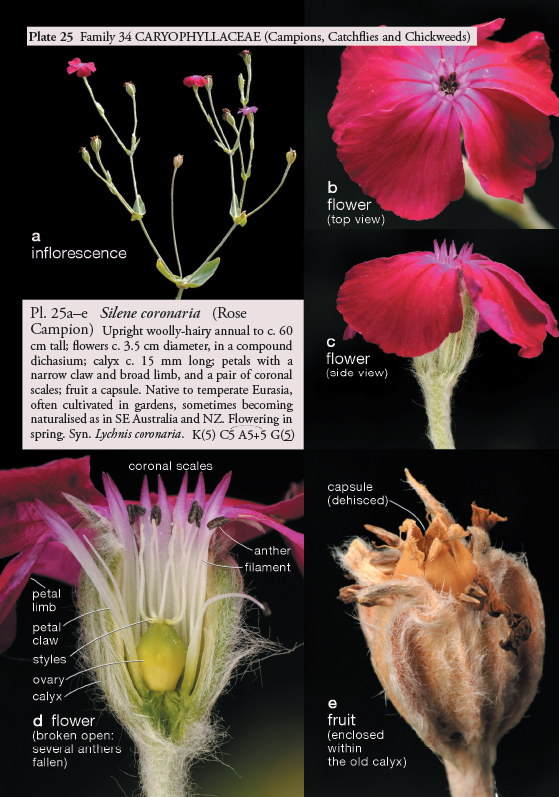

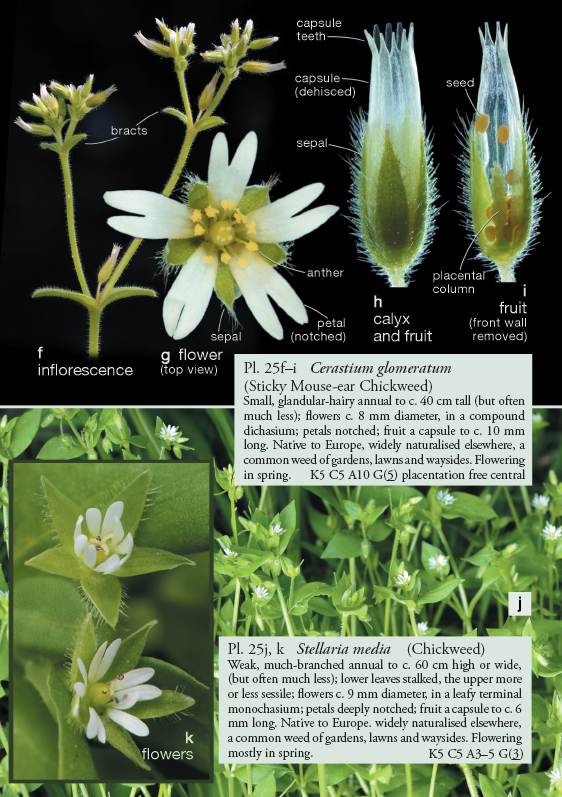

25 Family CARYOPHYLLACEAE

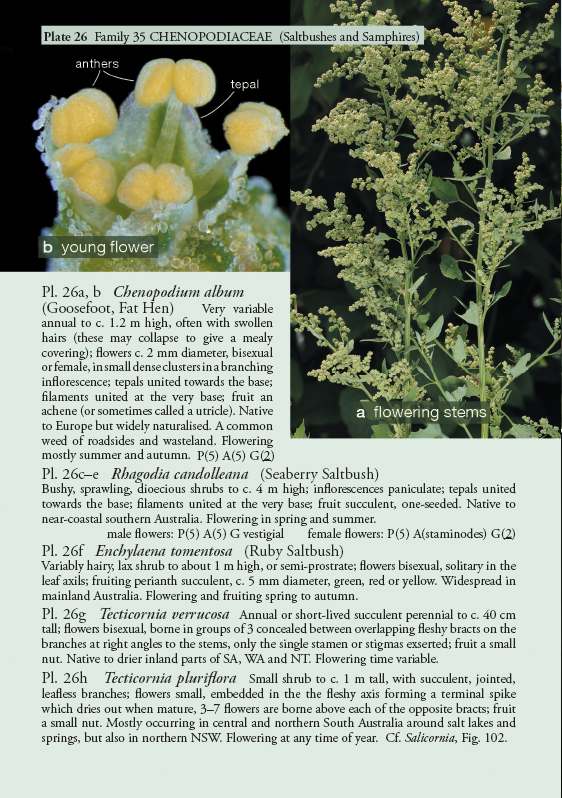

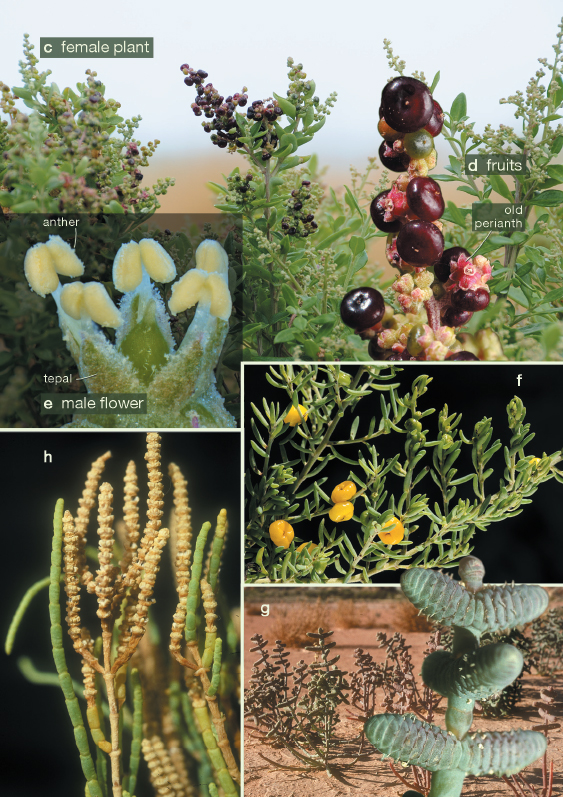

26 Family CHENOPODIACEAE

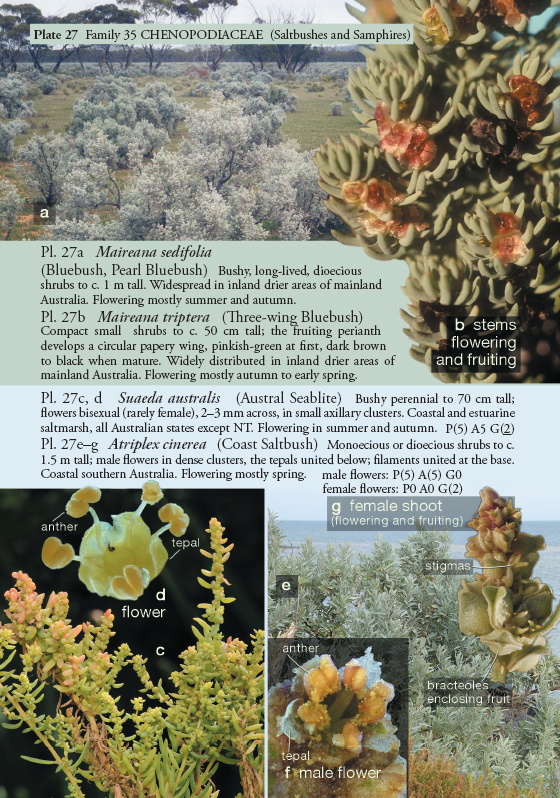

27 Family CHENOPODIACEAE

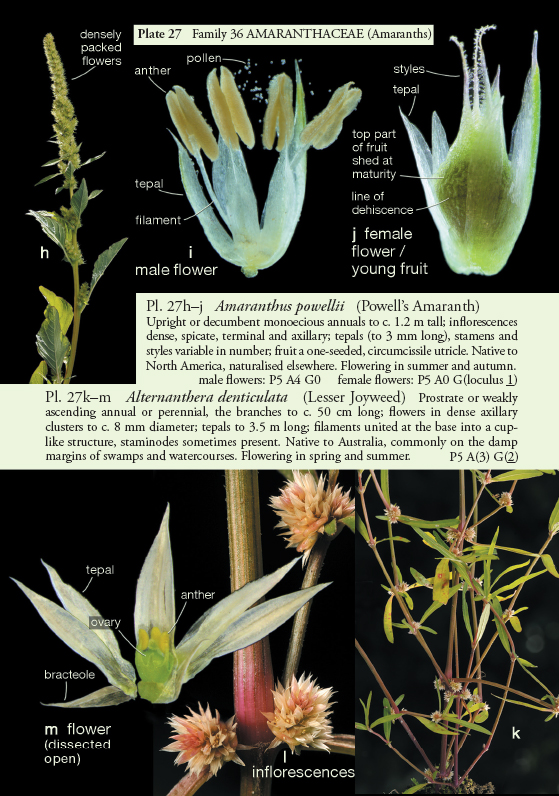

Family AMARANTHACEAE

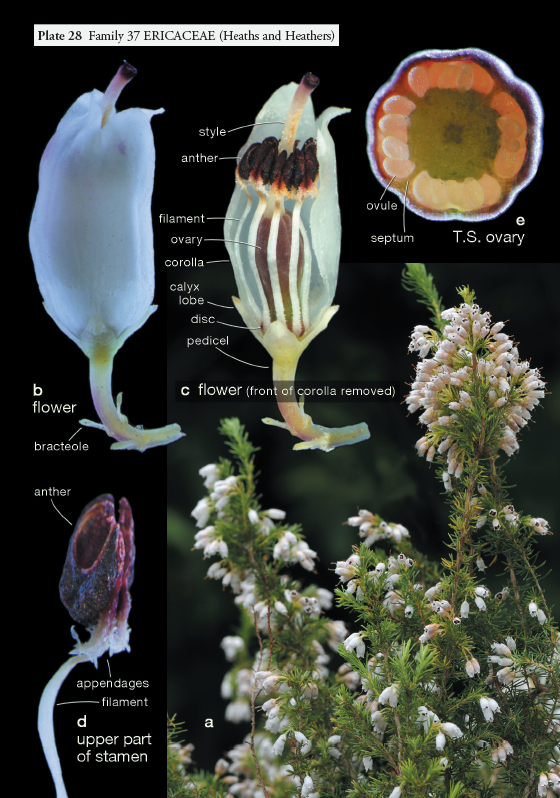

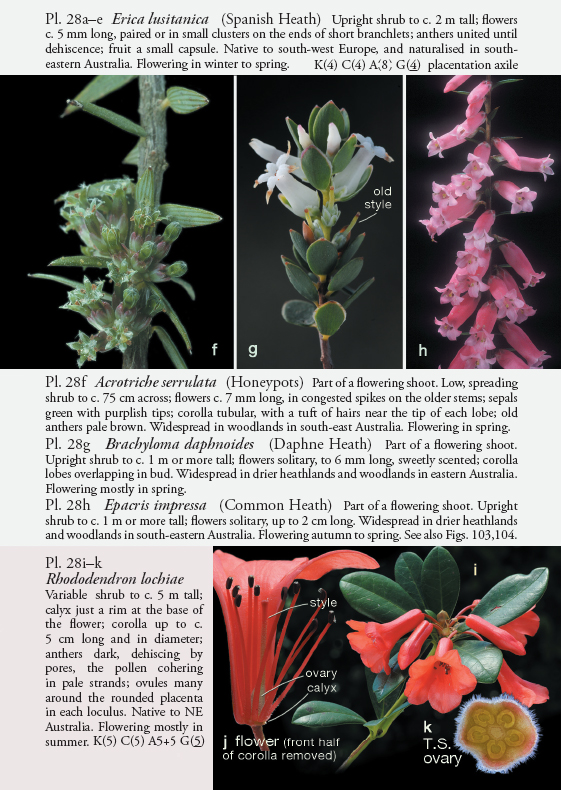

28 Family ERICACEAE

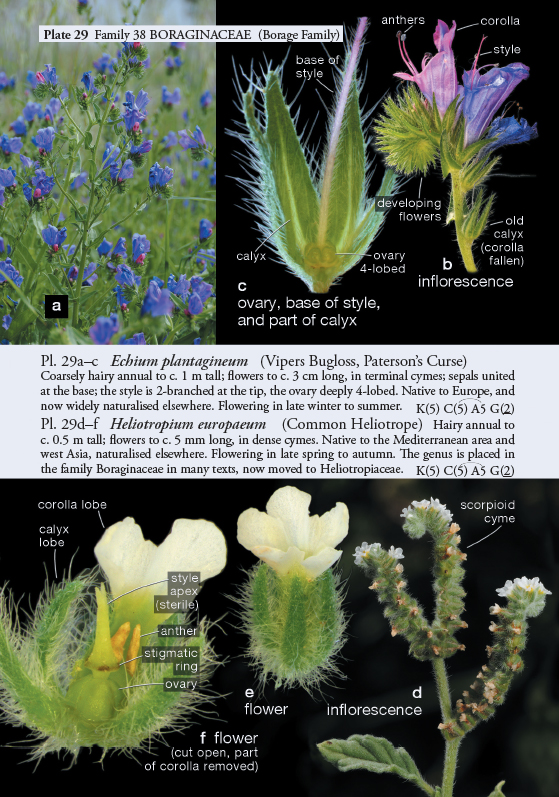

29 Family BORAGINACEAE

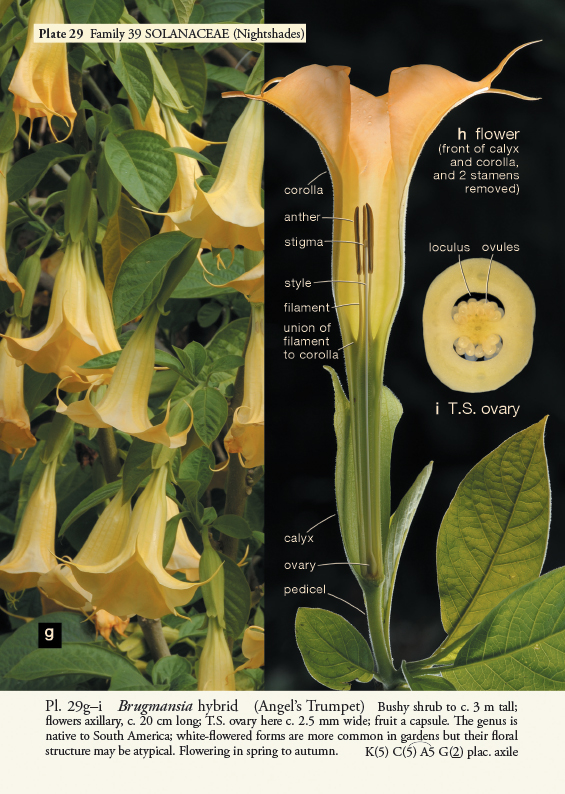

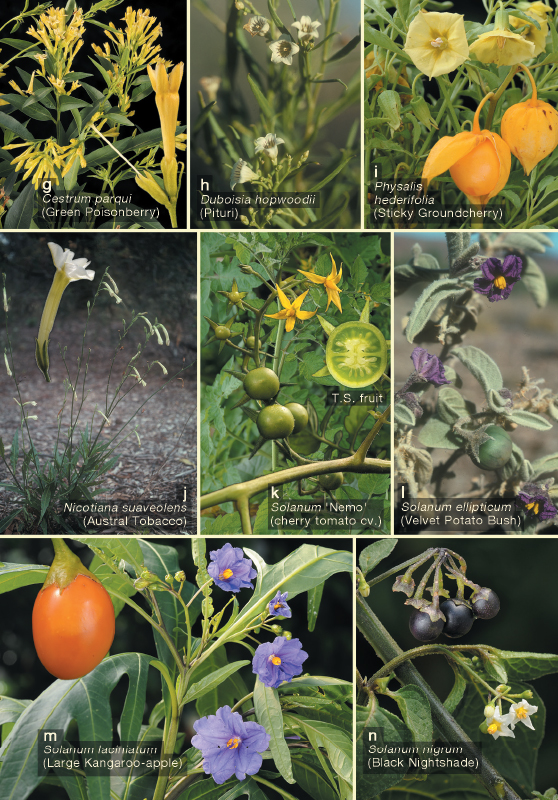

Family SOLANACEAE

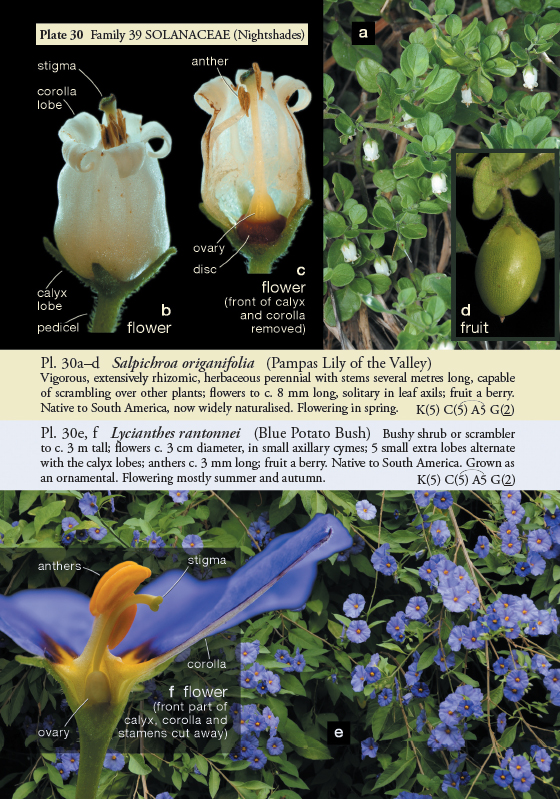

30 Family SOLANACEAE

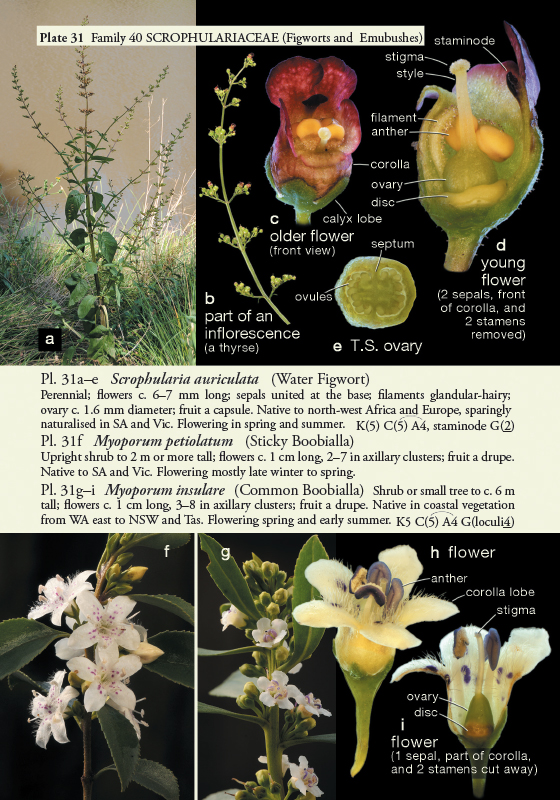

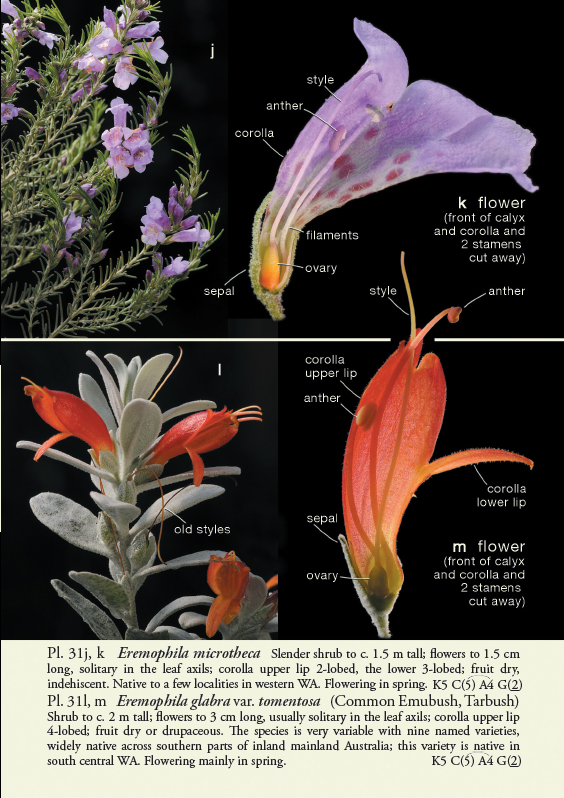

31 Family SCROPHULARIACEAE

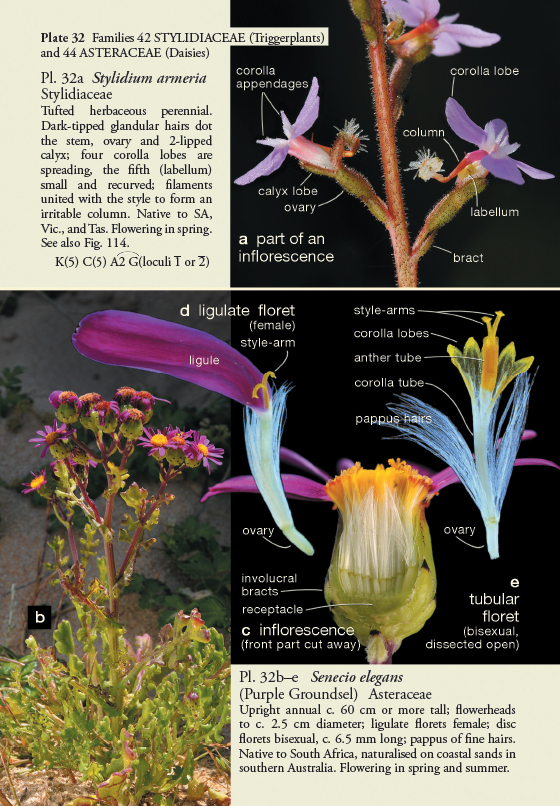

32 Family STYLIDIACEAE

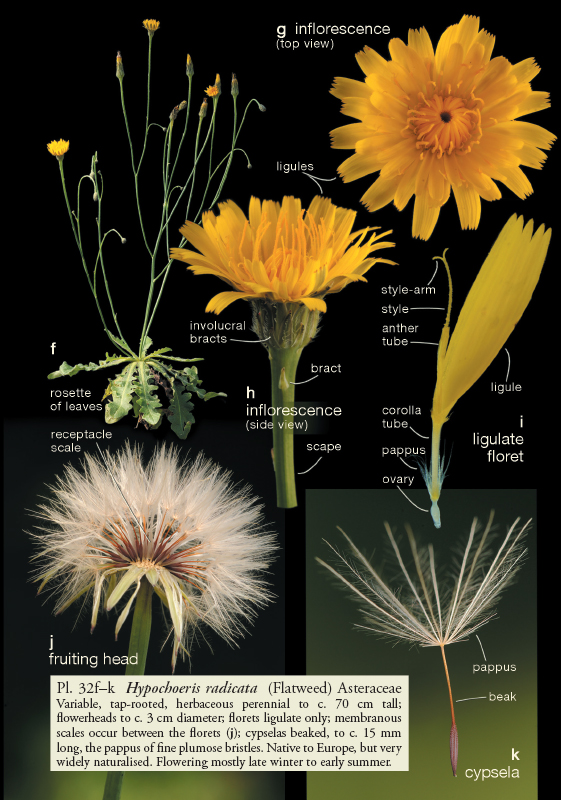

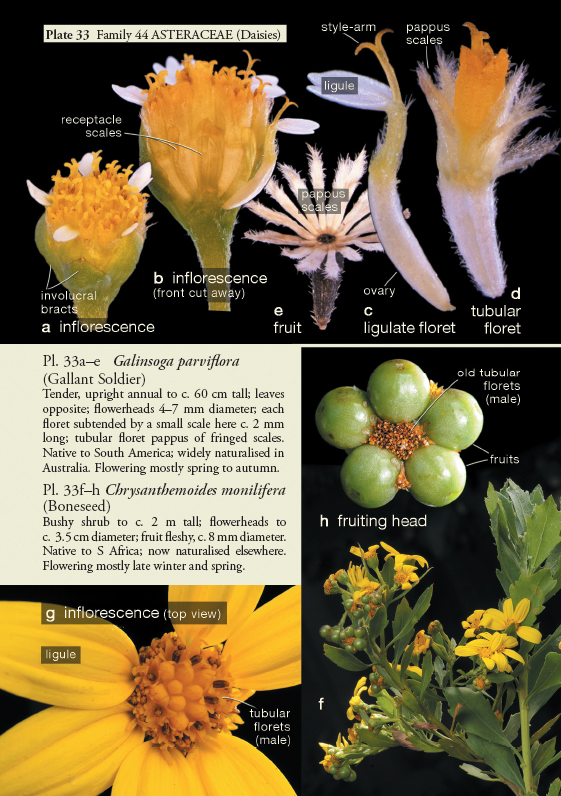

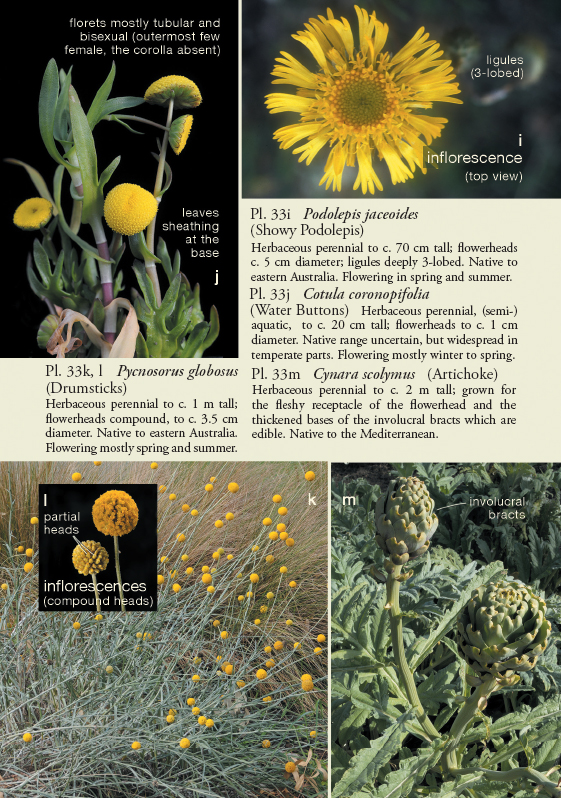

Family ASTERACEAE

33 Family ASTERACEAE

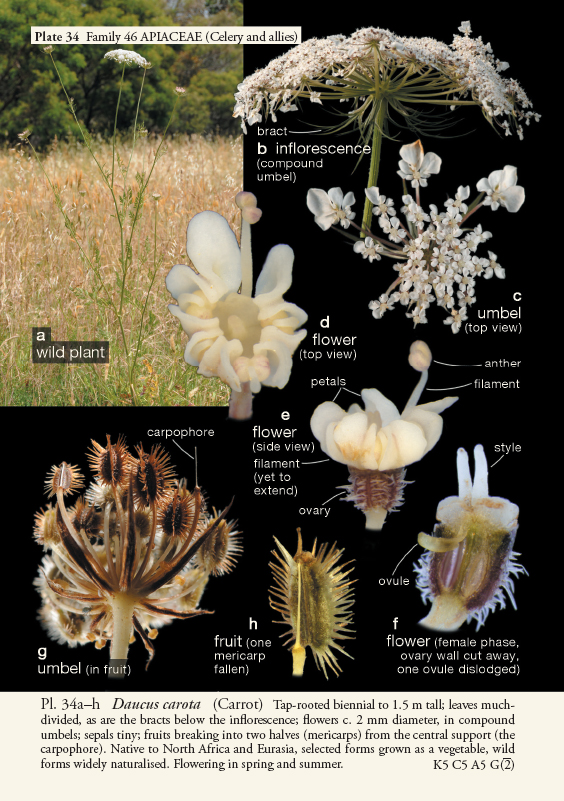

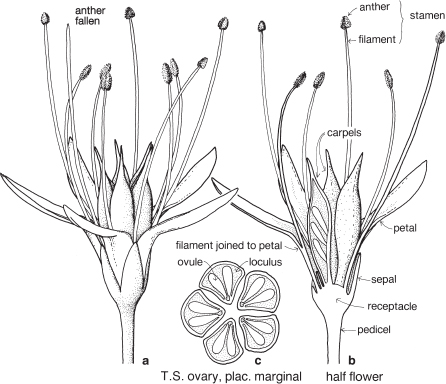

34 Family APIACEAE

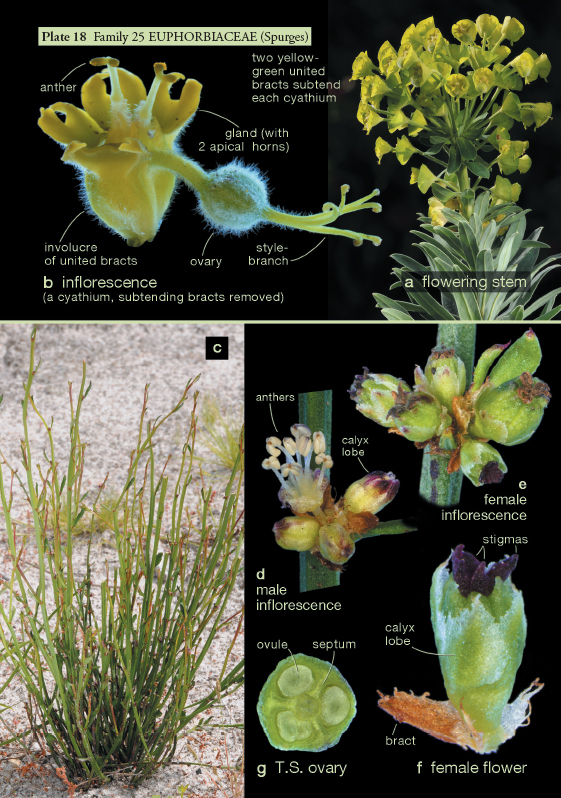

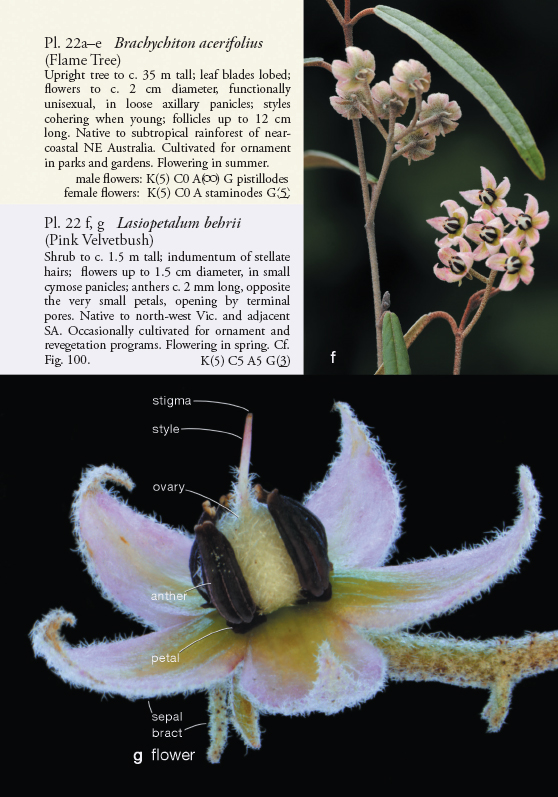

Pl. 18a, b Euphorbia characias ssp. wulfenii (Dalmatian Spurge) Herbaceous perennial to c. 1.5 m tall; flowers unisexual, much reduced, in specialised inflorescences (cyathia), each cyathium subtended by a pair of united bracts; fruit capsular, separating into segments. Native to the Mediterranean region, and commonly grown in gardens. Flowering late winter to spring. Cf. Fig. 78.

Pl. 18c–g Amperea xiphoclada (Broom Spurge) Small shrub to c. 50 cm or more tall, usually dioecious, often leafless, with angled branchlets bearing small clusters of flowers; calyx of male flowers c. 2 mm long, of females c. 3 mm long; fruit capsular, separating into segments. Endemic and often quite common in heathlands and woodlands in south-eastern Australia. Flowering mostly spring and early summer.

female flowers: K(5) C0 A0 G(3), ovule pendulous

male flowers: K(4–5) C0 A6–9 G0

Stonecrops and Orpines

This family is probably best known from the numerous succulent plants seen in gardens and rockeries. Species of Aeonium, Cotyledon, Crassula, Echeveria, Kalanchoe, Sedum and others are all commonly grown. Crassulaceae form a medium-sized family, widely distributed, and often found in dry habitats. The family is not well represented in Australia with only eight small endemic Crassula species and several members of various genera recorded as naturalised.

Plants often have a thick waxy cuticle which, together with the development of significant water storage tissues, sees them well adapted to arid environments. A further adaptation, of more scientific interest, is their particular metabolism in which stomates open mostly at night, minimising possible water loss. The subsequent production of carbohydrate through their particular biochemical process is referred to as crassulacean acid metabolism.

FLORAL STRUCTURE

| Flowers | Actinomorphic, usually bisexual. Parts often 4 or 5 but sometimes numerous. |

| Calyx | Sepals usually 4 or 5 (sometimes more), free or united. |

| Corolla | Petals usually 4 or 5 (sometimes more), free or united. |

| Androecium | Stamens usually the same number or twice as many as petals, free or united to the petals. |

| Gynoecium | Carpels usually 4 to 5 (sometimes more), usually free, sometimes united at the base, ovary superior. Each carpel with a small nectar-producing scale at the base (Pl. 1c). Placentation mostly marginal (sometimes effectively basal if carpels are united). |

| Fruit | Each carpel usually produces a small follicle. |

Plants are usually succulent herbs or subshrubs, with fleshy, exstipulate leaves in which the venation is obscure.

Australian species of Crassula are treated by Toelken (1981).

ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 55; Plate 1.

Succulent herbs (the Australian Crassula spp. very small) or subshrubs. Leaves fleshy with obscure venation. Stipules absent. Flowers actinomorphic, often with petals radiating (Pl. 1), or flowers appearing tubular (as in commonly cultivated genera such as Cotyledon and Kalanchoe). Carpels usually free.

Fig. 55 Sedum spectabile (Stonecrop, Ice Plant)

Succulent perennial herb less than 1 m high; leaves usually opposite, obovate, about 6–8 cm long; flowers pink, borne in dense corymbose cymes; the sepals very slightly united at the base but this is usually ignored; stamens of one whorl epipetalous; carpels free. Originally from China and Korea, now commonly cultivated (and some forms not displaying the expected structure). Flowering in autumn. Cf. Pl. 1. (a–b ×7, c ×12)

Legumes

This is a very large and important family, widely distributed in tropical, subtropical and temperate regions. After the Daisies and Orchids, it is the third largest family of Flowering Plants in terms of numbers of species.

The Legumes show wide variation in general appearance from large trees with buttressed trunks to diminutive ephemeral herbs, tendril-bearing climbers, woody lianas and even aquatics. A unifying feature of the group (with few exceptions) is the single carpel with a superior ovary which, in the majority of cases, develops into the characteristic leguminous fruit, often simply called a pod.