Introduction

On September 26, 1660, a woman named Zahra from the neighborhood of Jami‘ ‘Ubays on Aleppo’s southern wall was brought to court by her neighbors, including the local imam, Hajj Ahmad ibn Bashar. The residents of the quarter accused Zahra of being “mischievous,” an “evildoer,” a fallen woman who had veered “off the straight path” of Islam. “She brings strange men into her home,” the residents informed the judge, using a common euphemism for prostitution frequently found in the Aleppo court records. The residents requested that Zahra be removed from their neighborhood, and the court granted their request.1

This case of illicit sexual intercourse is one of several that appeared before shari‘a court judges in early modern Aleppo. The verdict against Zahra was consistent with that reached in other cases, namely, removal from the city quarter. However, many Islamists today would promote more severe punishments for illicit sexual intercourse, the crime of zina in Islamic law. Violent punishments for this crime, such as death by stoning, have been advocated by contemporary Islamic movements and incorporated into the legal codes of some Muslim countries as punishment for breaches of sexual morality in the name of a return to a more “authentic” Islamic law.2 Of course, the basis for stoning is not completely unfounded; it is a tradition that can be found in the hadiths of the Prophet Muhammad and the caliph ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab (634–44) who apparently encouraged the practice after the Prophet’s death. Later juridical writings gave the practice more support, but the sentences handed down by the courts in the Ottoman period tell another story. In Ottoman Aleppo, the shari‘a court regularly recorded nonviolent, noncorporal punishments in cases like Zahra’s. Not a single documented case of stoning was found in more than three hundred years of shari‘a court records studied.3 So, how is it possible that the punishments handed down by the shari‘a courts in Aleppo are so radically different both from the precedents established in the early Islamic period and from the punishments prescribed by later Islamic legal theorists? How did jurists reconcile the contradictions between the theoretical, doctrinal law that they were trained in as students and the law they practiced in the shari‘a courts?

According to the shari‘a, Zahra’s crime was zina, which Joseph Schacht has defined as “fornication” or “any sexual intercourse between persons who are not in a state of legal matrimony or concubinage.”4 Many discussions of Islamic law seek a normative definition for crimes in an attempt to create parallels with legal concepts that Western readers would find familiar. However, in the end they fail to flesh out all the dimensions of crimes that have been discussed and debated in a vibrant Islamic juridical discourse over many centuries. Zina, as defined through the volumes of juridical writings produced by Muslim scholars, encompasses a wide range of sexual violations: it is an umbrella category for several offenses found in modern Western codes of law, including adultery, prostitution, procurement, abduction, incest, bestiality, sodomy, and rape. To redefine our concept of the crime demands an examination of some of these complex juridical conversations; hence, I have conducted an archaeology of zina crime beginning with its earliest references in the Qur’an. Later, criminal cases of zina will be tested in one locality, Aleppo, Syria, in order to better understand, as much as can be done given the limitations of the sources, the way in which zina-related cases were treated in the court of law.5 Furthermore, zina is discussed within the larger context of public morality in a specific geographical setting, in order to understand the way that a local court and its surrounding community defined the boundaries between permissible and forbidden behaviors.

Several studies of law and society have been produced in recent years, but Aleppo has not been part of that conversation. Historians have been engaged in various kinds of study with court records, using them to reconstruct the social and political history of Aleppo, such as the works of Abraham Marcus and Margaret Meriwether. Aleppo’s economic history and its non-Muslim communities have been discussed in two carefully crafted monographs by Bruce Masters, but for Syria as a whole, no one has contributed as much as Abdul Karim Rafeq, who has used court records from four major cities in the Syrian archives, including Aleppo, and has written on numerous political, economic, and social issues.6 One study in particular focuses on public morality in eighteenth-century Damascus and raises important questions of gender and morality. Rafeq argues that the century marked an increase in various forms of moral breaches, including prostitution, suicide, and troublemaking. Importantly, for this study, he argued that “quarter solidarity” provided the vehicle for adjudication of crimes against the moral order. Many of the arguments advanced in this important article are tested in this study.7

All the cases used in this study were found in the shari‘a court records (sijillat al-mahakam shar‘iyya) of Aleppo, an invaluable source for our understanding of the practice of Islamic law. Aleppo’s court records illustrate the workings of the Ottoman administration in the period under study. Almost all the records are in Arabic, although a few are in Ottoman Turkish. I have also consulted collections of Ottoman kanunnames and Ottoman fatwas, which present the perspective of imperial law, in an attempt to give a holistic approach and to cover some historical and legal material pertaining to the practice of the central Ottoman state. A combination of materials, including selections from the vast amount of fiqh documents available in Arabic, particularly those from the Hanafi school of law, have been used in an attempt to compare legal theory with court practice. The virtual absence of secondary studies dealing with zina and Islamic law has led me to rely predominately on primary sources from Syria, namely, the records in the Syrian National Archives (Markaz al-Watha’iq al-Tarikhiyya) and juridical literature (fiqh and fatwas). As a result, the scope of the Islamic legal literature was quite large, so I selected volumes that would have influenced a Hanafi jurist in the period under study.

The methodology I have chosen has been influenced by several fields; comparative studies in Islamic law and society have been particularly influential.8 Several studies in the past decade have chosen to compare the shari‘a court records to juridical writings found in fiqh and fatwas in order to compare doctrine with the actual practice of the court. This has been the methodology of Amira Sonbol, who has cross-referenced Egyptian court cases with juridical texts. Judith Tucker has compared fatwa literature with court records in her study of gender discourses in Ottoman Syria and Palestine. Leslie Peirce’s microhistory of Ottoman ‘Aintab also compares and contrasts the body of juridical literature with an examination of practice as shown in the court records.9 I have chosen to borrow this comparative model of analysis in my examination of Aleppo court records, with two exceptions.

First, after examining the state of the archives in Damascus, including the manuscripts now housed in the Asad Library, I discovered that there were only a few fragments of fatwa collections from Aleppo; however, none of the ones with a discussion of zina were from Aleppine jurists, which made it impossible to compare Aleppine fatwas with the local court records in a systematic way. That being said, a few fatwas are used from those collections and other fatwas that were cited within the court records themselves, composed by the hand of the court scribe. Hence, I have used the imperial fatwas of Ebu’s Su‘ud Efendi, supreme religious leader (sheikhul-islam of the Ottoman Empire from 1545 to 1574) during the reign of Süleyman I in order to understand better the imperial discourse on gender and sexual criminality. These fatwas are examined in chapter 2 in conjunction with the imperial law codes, the kanunnames.

The second way that I depart from some of the models I have chosen is that I do not engage in a microhistory of Aleppo based on the court records. Microhistory has been popular in the field in recent years, but there are a number of reasons for my not having chosen that approach.10 To begin with, the court records found in Aleppo, as will be demonstrated, are quite formulaic and rarely provide the lengthy narratives and richness of detail of, for example, the Inquisition cases that have formed the microhistories of other parts of the world.11 Furthermore, the nature of the sources and the way in which the material is recorded make it difficult to understand the underlying motivations of the individual participants. Any attempt to understand those motivations is quite speculative.12 Therefore, I have chosen to analyze only the bits of data I found useful from the sijills—names of defendants and plaintiffs, neighborhoods, social titles, narrative choices—and use this information to understand the adjudication process.

My method of digging through the layers of zina discourse in order to understand the history of this crime and the way it was treated in court is intended as an attack on the pervasive discourse of Muslim sexuality that has real effects on the way shari‘a is interpreted today. By systematically documenting a legal discourse on illicit sexuality, I seek to fill in a crucial gap in both academic and lay understanding of the shari‘a and to continue a conversation initiated by Fatima Mernissi in the late 1980s, when she broke down a centuries-old barrier to female interpretation of Muslim traditions.13 Her original critique published twenty years ago is just as important today as it was then.

Current Islamist discourse often looks to the doctrinal prescriptions of the law and takes them at face value, ignoring the ways that Islam allowed for flexibility of interpretation. In many ways, the Islamist understanding of Islamic law is similar to that of the Orientalist tradition: timeless, stagnant, and rigid in its interpretation of law.14 Even historical precedents are often taken out of context in order to suit political agendas. Feminists like Mernissi, who discusses this preoccupation with the past and the way that it has been used to advance the patriarchal interests of contemporary politicians, call it the “misuse of memory.”15 This problem is by no means exclusive to the postcolonial Muslim world; rather, it is a cross-cultural phenomenon. The “misuse of memory” can be seen in various aspects of twentieth-century Islamic revivalism, in which crimes against the moral order, specifically zina, have often been punished with the death penalty, ignoring the larger legal process established by jurists as well as the way in which such cases have been treated historically. Hence, the process of resuscitating draconian punishments found in Islamic doctrine but not in judicial practice has been in many ways ahistorical, an example of the all too familiar process of the invention of tradition to shore up a supposedly failing moral order. Advocates have selected some passages of hadith to support the implementation of stoning, since it is suspiciously absent from the Qur’an, yet have simultaneously disregarded hadiths that provide strict criteria for conviction. This revivalism has also been encouraged through the republication of several classic treatises on the law that advocate corporal punishment for zina. Browsing through bookstores in the Arab world reveals a flood of newly (re)published works on women and morality in Islam, most of which, it should be emphasized, were originally written during the first five Muslim centuries. These publications, coupled with a dynamic contemporary Islamic discourse on morality and gender, have resulted in a particular convergence of the past and the present—the use of history to justify an authoritarian political agenda concerning women and morality. Therefore, exploring the “actual” historical position of women, gender, and morality becomes even more pressing as it stakes out the ground upon which the battle over morality in Islamic law will be fought.

This project is also part of an ongoing conversation about the theories and practice of Islamic law. Much of our understanding of Islamic law has been shaped by Western theories, such as those of Max Weber, who embraced the Oriental despotism model originally formulated by Marx and Engels (and elaborated further by Karl Wittfogel in the 1950s) to describe the political development of Asia.16 In this theory, the court of law is a microcosm of the despotic state, in which the judge (qadi) sits as the patriarch of his courthouse. Weber, and others, on the basis of no particular body of evidence, argued that the judge arbitrarily meted out punishments as he saw fit, without rhyme or reason. The system, called kadijustiz, has been described as one in which “judges never refer to a settled group of norms or rules but are simply licensed to decide each case according to what they see as its individual merits.”17 Weber argued that the reason kadijustiz was prominent in Islamic society was owing to the legal structure in which outside forces wielded little influence on the decisions of the judge, a position that parallels the stance of the sultan vis-à-vis the state. The judge administered justice alone, his decision was final, there was no appeal system, and justice was swift and immediate. Hence, there were no lawyers to influence judicial decisions, nor did the Islamic world have a commercial class that could influence legislation and check the powers of the polity. For Weber, this situation marked a departure from the Western legal system, making Islamic law exceptional.18 Orientalists long held that Islamic law was practiced arbitrarily and its legal tradition was stagnant, although such fundamentally inaccurate notions have been challenged by recent scholarship.19 A revisionist approach to Islamic law and society has developed over the past two decades in the work of Brinkley Messick, David Powers, Muhammad Khaled Masud, Judith Tucker, Wael Hallaq, and others, who have demonstrated convincingly that Islamic law developed as positive law, based on historical precedent and as part of a rational body of legal thought.20

A major part of the debate has been centered on the history of Islamic law and its development throughout the centuries. Scholars have claimed that (Sunni) Islamic law was stagnant because of a process called “the closing of the gates of ijtihad (legal reasoning)” in the ninth century. It was in that century that after two centuries of debate jurists began to view the corpus of work developed as exhaustive and complete. It was indeed a real debate, discussed by both foreigners and Arabs, including the travel narrative of Mouradgea D’Ohsson and the writings of Syrian jurist Husayn al-Jisr, respectively.21 Whereas Orientalist scholars argued that the gate was closed, new scholarship has argued to the contrary. This revisionist school in the field of Islamic law and society developed after 1984, when an important article by Wael Hallaq entitled “Was the Gate of Ijtihad Closed?” was published. Hallaq demonstrated that although Orientalist scholars argued that ijtihad had been stifled, jurists continued to refer to the process in their writings. Soon after Hallaq opened the debate, several books were published that focused on the consistent use of ijtihad in the formulation of fatwas. Authors such as Messick, Powers, and Tucker have worked extensively with fatwa literature that existed after the alleged disappearance of ijtihad to in fact show that it was a vibrant, ongoing tradition in Islamic law.22 Later, Hallaq published an article that connected the process of issuing fatwas (ifta’) to legal manuals to demonstrate the connection between doctrinal law found in juridical writings and fatwas, both of which use legal reasoning but also have a basis in the living law in Muslim communities.23

One of the overarching goals of this study is to determine the way Islamic law was practiced in the courts of early modern Aleppo. The examination of multiple sources reveals a discrepancy between the theoretical prescriptions of the law found in legal manuals, that is, what could be called doctrine, and the practice of law in the courts.24 Doctrine produces what could be called a “symbolic construction” of gender relations that can be found in the writings of Muslim jurists versus the sometimes complicated “social relationship of gender” that is, to quote Judith Tucker, “the product of the historical development of human experience, a relationship that changes, evolves, and adapts in rhythm with a changing society.”25 Does this adaptation mean that law was practiced arbitrarily as kadijustiz? The answer to that question is an unequivocal no. Despite the disparity between the theory and the practice of law in Aleppo, there is a consistency in the verdicts that judges issued in matters of public morality and the crime of zina. In fact, it is quite difficult to find much change in the way these crimes were punished throughout the 359 years of court cases used in this study.26 I argue that this lack of change in punishment is a result of the consistent application of the local interpretations of law by the numerous judges who entered the court. It was customary for judges to take traditions of law into consideration so long as it did not overtly contradict the shari‘a. This consistency should not be mistaken for stagnation or lack of development. The cases themselves vary in frequency and type within various periods, marking social and political changes in Aleppine society. Through these changes, societal norms for treating deviancy, rather than regulations laid down by the state, were consistently upheld by the courts.

This study of moral deviancy is useful for challenging the dominant paradigms found in Orientalist scholarship about law and society for several reasons. First, the study of morality and deviancy forces us to throw out Orientalist misconceptions about sexuality and law in the Islamic world. The fact that an active, illegal flesh trade existed in Aleppo demonstrates that an underground economy functioned there, as in many other places, and opens the door to possible comparative histories of gender and morality in the future. Second, it forces us to look at the way in which law functioned in society, rather than isolated solely as a text. Textual analysis alone simply does not get at the agency of local actors shaping the practice of law in their own communities. This book will demonstrate that communities defined deviant behavior outside the Islamic juridical framework, yet the courts adapted to those definitions. This process of negotiation between the community and the court emphasizes the effects that communities had on their own legal culture. So we are dealing with not only divine law as found in the shari‘a, and Ottoman imperial law, but also the way in which law operated on its most local level, in Aleppo’s neighborhoods. Michel Foucault has argued that nineteenth-century European notions of the normal and the abnormal “actually originated in social practices of control and supervision [surveillance].”27 Therefore, to write a history on the subject of deviancy, one must take into account the various social practices that enforce these definitions, as well as the discourse that develops on an official level, particularly through the law because of its special influence in shaping views toward sexuality by delineating the boundary between licit and illicit sexuality. Law is a reflection of power that is diffuse in society on the local level and in its legal discourses on illicit sexuality. The way that the community used the court in Aleppo illuminates the reciprocal relationship between the court and society. The court itself, in order to be deemed legitimate, needed public approval, which can be seen in the accommodations to local conceptions of morality illuminated by instances of community policing and en masse testimony illustrated in this volume. This notion stands in stark contrast to scholarship that has presented the courts as neutral. As demonstrated in this study, the court accommodates the interests of the community in several ways, sometimes even allowing the community to use hearsay and circumstantial evidence in zina-related crimes, that overrun the rules of evidence outlined in the shari‘a.

Therefore, following this methodological example, the process of historicizing and contextualizing the legal discourse on zina is documented in two parts: zina discourses and law in practice. The first two chapters of the book deal with legal theory found in early Islamic juridical writings and in Ottoman law. Chapter 1, “Zina in Islamic Legal Discourse,” outlines the way in which Islamic law viewed the crime of zina, using some of the Hanafi juridical literature available on the subject. This chapter situates Islamic law within the context of prescriptive literature that contains variations in interpretation presented by different jurists, focusing on writings of the Hanafi school, the dominant legal school in the Ottoman Empire. Chapter 2, “Zina in Ottoman Law,” looks at the way in which the crime was dealt with by Ottoman jurists. The Ottomans converted the draconian punishments found in the shari‘a into a set code of imperial laws, the kanunnames, which prescribed a system of fines and lashing instead of the death penalty in most cases. Use of Ottoman fatwas in this chapter also demonstrates a continued interpretative tradition of the shari‘a and the ongoing development of a legal discourse during a period that some have argued marked a closure of legal interpretation.

The second part of the book looks at the practice of law in Aleppo. Chapter 3, “People and Court: Policing Public Morality in the Streets of Aleppo,” is an introduction to the city of Aleppo and its historical background from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, exploring the city’s structure and its connections to the rest of the world. This chapter introduces the shari‘a court record as a source for social history. Class composition and the role that class and communities played in policing crime in the city are also detailed. Local neighborhood representatives policed their own neighborhoods, apprehending those residents who violated the moral code and bringing them to justice. The fact that neighborhoods initiated these cases reflects the civic function of the court as a mediator in public affairs. By focusing on the local interpretation of law and local initiatives of neighborhoods in the court, the importance of the people in shaping and implementing the law is revealed. Chapter 4, “Prostitutes, Soldiers, and the People: Monitoring Morality Through Customary Law,” discusses the way in which prostitution was policed and punished in Aleppo. It compares data found in Aleppo with studies of other parts of the Ottoman Empire and argues that a consistent pattern of banishment for prostitution existed in the empire as a whole, despite shari‘a prescriptions to the contrary.

Chapter 5, titled “In Harm’s Way: Domestic Violence and Rape in the Shari‘a Courts of Aleppo,” investigates cases of violence against women in the court. It seeks to dispel the Orientalist notion that the crime of rape did not exist in Islamic law, pointing out that language has been a major cause of this misconception; therefore, an analysis of terminology is included to illuminate the presence of rape as a legal category in Islamic rulings. This discussion will also highlight cases of rape and domestic violence that appeared in court. Together, these chapters attempt to challenge some pervasive assumptions about the nature of law and Ottoman rule that continue to persist in the field of Middle East studies. The study of law and vice in Aleppo will, I hope, generate future discussion about the nature of law and society in other parts of the Ottoman Empire.

ALEPPO AND ITS HISTORY

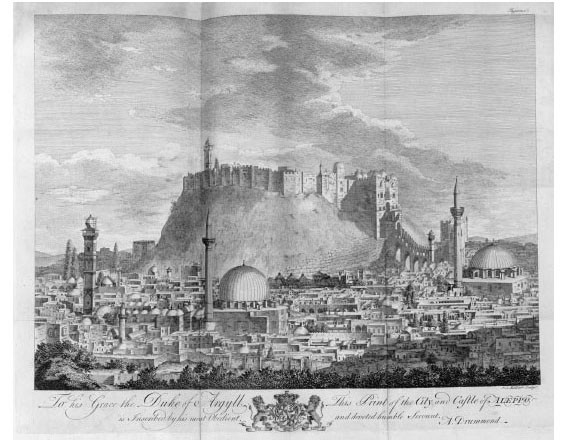

“The Aleppine is a gentleman, the Damascene is a pessimist, the Jerusalemite is a helper and the Egyptian is a thief.”28 This saying conveys the popular attitudes and stereotypes toward the residents of some of the Ottoman Empire’s major metropoles. The fact that the Aleppine was considered a gentleman (Halabi chalabi) tells us something about the way the northern province of what is today Syria was perceived in the early modern period. It is a city with a vast history that can be traced as far back as the second millennium b.c.29 The local name for the city, Halab, is derived from the Arabic verb meaning “to milk,” relating to the popular belief among Aleppo’s residents that the Prophet Abraham once stopped in Aleppo to milk his flocks there.30 The city has been the site of several invasions throughout history, from the Hittites, Aramaeans, Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Crusaders, and Turks. Because of its many cultural influences throughout the centuries, Aleppo has a distinct local identity (ill. I.1).

Despite its importance in regional trade and strategic location at the crossroads between Anatolia and the Arab world, Aleppo was never used as a capital center, except for a brief period under the rule of the Hamdanid Sayf al-Dawla (r. 944–67). Although it lacked the political title of capital, it was long considered the economic capital of the region, attracting a diverse set of immigrants from all over the Middle East, including vibrant Christian and Jewish communities that date back to pre-Islamic Byzantine rule. Khalid ibn Walid’s conquest of the city in 636 brought it under Muslim rule. It is at this time that the first mosque was built in the city, situated along a colonnaded street constructed during the Roman period.31 Well after the Muslim conquest, Umayyad Aleppo still had a large population of Christians. It took more than a century for the authorities to build a Great Mosque on the site of the Roman-era market to serve the small but growing Muslim population.

I.1. Sketch of Aleppo in the eighteenth century, from A. Drummond’s Travels Through Different Cities . . . and Several Parts of Asia (London, 1754). Courtesy of the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin.

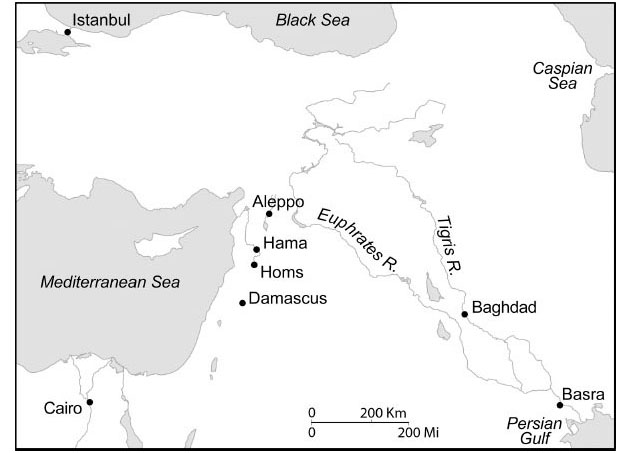

Aleppo had a tumultuous history after the massive influx of Turkish nomads into the region who set up a series of independent and often mutually hostile Seljuk emirates (1058–1194). The general instability of the region was evident during the Crusades (1096–1291) in which the city-states of Tripoli, Aleppo, and Damascus were some of the first to be captured, largely because these Seljuk states were bitter rivals, which put the Crusaders at a military advantage. Nur al-Din Zangi (r. 1154–74) would eventually put an end to these rivalries by taking over the region and creating a united front against the Crusaders. Salah al-Din (r. 1169–93), in many ways Nur al-Din’s “successor,” took advantage of that unification and eventually conquered Jerusalem in 1187 (maps I.1 and I.2).

Map I.1. Regional map of the East Mediterranean. Produced by Joseph Stoll.

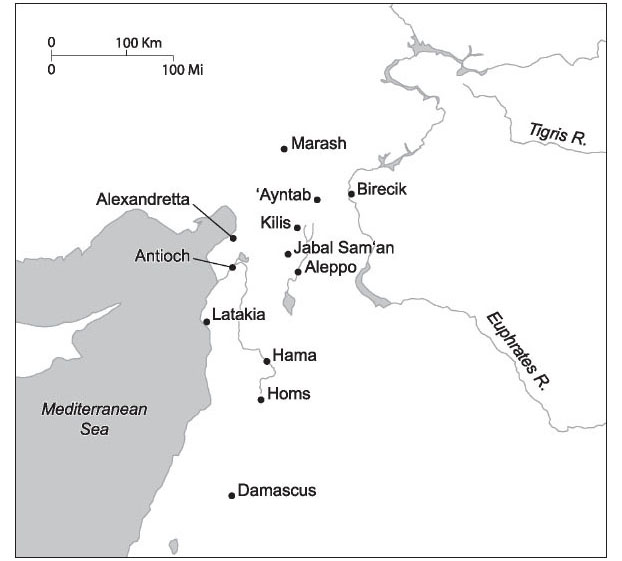

After the Crusades subsided, new power struggles took place in the region, particularly between the ailing Byzantine Empire and other waves of invading Turkish nomads who would later unite under the leadership of Osman (d. 1324), after whom the Ottoman Empire would be named. In 1453, the Byzantines were dealt a crushing blow when their capital, Constantinople, was conquered by Mehmet II (1444–46 and 1451–81). This defeat was only the first of several steps toward the consolidation of Ottoman rule throughout the region over the next century, culminating in the capture of Syria by Sultan Selim I (r. 1512–20), followed by the conquest of Palestine, Egypt, and the holy cities of Mecca and Medina in the Arabian Peninsula. The conquest of Mamluk Syria (1250–1517) took place as a result of the Battle of Marj Dabiq on August 23, 1516, when the Mamluk leader Sultan Qansuh al-Ghawri was defeated by the Ottoman army. Although Aleppo welcomed its new Ottoman ruler, Ottoman authority was not left unchallenged. By the time Süleyman I (r. 1520–66) took the throne, the governor of Aleppo, Janbirdi al-Ghazali, had inspired a revolt against the empire. Al-Ghazali did not have the support of the local population, who resisted him until the Ottomans returned with reinforcements, retaking the city in 1520 (ill. I.2).

Map I.2. Aleppo and its environs. Produced by Joseph Stoll.

With the further expansion of the Ottomans into Iraq (Baghdad was captured in 1534 and Mosul in 1549), the trade routes from East Asia were secured and Aleppo continued to prosper.32 As had been true of many of their predecessors, the Ottoman rulers generally absorbed the cultures of areas they conquered, which left local custom and tradition relatively undisturbed. As the Ottomans conquered Arab lands, they formed links with local elites and employed them in state service as members of the ‘ulama, neighborhood representatives, heads of guilds, and representatives of the urban noble class (a’yan). These Ottoman employees served as the eyes and ears of the sultan in the provinces and facilitated the absorption and management of the Arab lands. The Ottomans chose to continue some local traditions, such as the use of neighborhood representatives as mediators between the state and the local population, as will be demonstrated later. Furthermore, in the area of law, the Ottomans continued the tradition of using Arabic as the primary language of the courts in these newly conquered lands. The fact that the Ottomans, in the Arab lands as earlier in the Balkans, administered the provinces without imposing Ottoman Turkish on the population kept local identity intact. In Aleppo, locals would eventually acquire some Turkish expressions because of the city’s proximity to Anatolia, the effects of acculturation, and because of the opportunities for advancement that knowledge of the language presented, but they were under no pressure from the imperial authorities to do so. Instead, local identities were based on language and custom, and sometimes on ethnicity or region.33

I.2. The citadel of Aleppo from its main entrance. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, LC-DIG-matpc-07217.

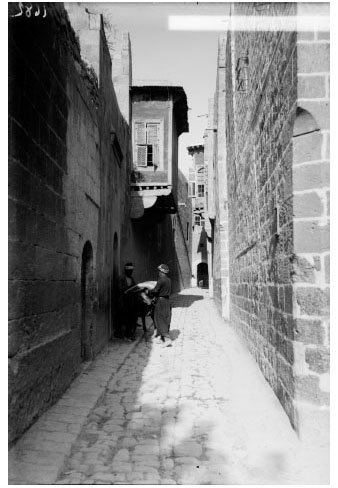

Aleppo in the Ottoman period consisted of what is now the city center overshadowed by a massive citadel, surrounded by walls and nine gates, encompassing about one and a half square miles. Such walls served a protective role for the residents; within the walls were clusters of narrow alleys and closed culs-de-sac that constituted up to 50 percent of the total streets in the city.34 Many alleys were gated at night in order to protect residents. The nine gates of the old city also had doors that were closed and locked to protect the city from both domestic crime and foreign invasion. Homes were packed closely together; the close proximity of houses increased the amount of surveillance in neighborhoods, but made privacy a difficult commodity to come by. Therefore, although limited privacy could be viewed as a drawback, it offered residents a level of security as a benefit (ill. I.3).

The city, located at a cultural, geographical, and economic crossroads in the region, contained a diversity of ethnic and religious groups within its borders. Ethnic Arab, Kurdish, Turkish, Armenian, Albanian, Bulgarian, Romanian, Serbian, Jewish, Assyrian, Greek, Maronite, and Gypsy populations lived within the city. The urban geography of Aleppo is a reflection of the mosaic of cultures that have inhabited the city throughout its history. For example, neighborhood names reflect the historic Kurdish and Persian residents who dwelled within them. Quarters such as Banqusa, Karliq, Tatarlar, and Maydanjik in the eastern suburbs of the city were full of tribal migrants such as Turkmen, Kurds, and Bedouin. Inhabitants of these same neighborhoods often appear in the court records “as perpetrators of theft and murder.”35

Aleppo’s economic success increased with an influx of Venetian and other Italian traders who sought goods such as silks, carpets, glass, steel, and spices.36 The trade routes shifted after the fall of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia in 1375, and by the fifteenth century Aleppo had become the principal center for the commerce between Iran and Europe, and increasing demand for Iranian silk would keep the economy of the city alive.

Aleppo had advantages over Damascus in that it was easily accessible to European traders, lay relatively close to the port of Alexandretta, and possessed goods in its market that Europeans sought to buy and export to their homelands. Damascus, on the other hand, was closer to the Lebanese ports, but the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon mountains lay between it and the Mediterranean, making travel hazardous.37 As the major economic hub of the region, Aleppo had a reputation as a sophisticated cosmopolitan center, which is reflected in popular sayings such as “The people of Aleppo have taste and manners.”38

I.3. A scene from a residential neighborhood in Aleppo. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection, LC-DIG-matpc-02164.

By the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Aleppo was one of the largest and most prosperous cities in the Ottoman Empire, ranking third after Istanbul and Cairo. Its location between Europe and East Asia made it a crossroads of trade. The city was full of foreign merchants within its caravansaries, conducting business by day and lodging on the upper levels of the structures by night. Merchants from Asia and Europe were engaged in the lucrative silk trade, and many Europeans lived as expatriates in Aleppo; members of these expatriate communities often appeared in the courts of Aleppo in both commercial contracts and criminal cases. As a result, the city had a diverse population of Italian, French, and British traders. Bruce Masters notes that by 1750, Aleppo was fully integrated into the world economy dominated by Europe and capitalism, but he is careful to note that this position was mostly the result of specific Ottoman economic policies that granted more and more leniency to foreign traders. These traders were given commercial privileges through the Capitulations (imtiyazat) that “granted an extraterritoriality to the European merchant trading communities, in effect making them mini-nations in the Ottomans’ midst.”39 Aleppo’s strategic location next to Anatolia gave it special proximity to the Ottoman capital and other Turkish cities that lay to the north, an advantage for local and foreign merchants alike.

The Ottomans offered opportunities to these foreign traders in hopes of strengthening the domestic economy, but for various reasons it did not happen. What followed was a reversal of the sixteenth-century Muslim domination of the world economy, particularly the East Asian spice trade, and the seventeenth century eventually saw the emergence of English and Dutch commercial supremacy.40 Their prominence was especially notable in the spice trade, where English naval power succeeded in increasing its economic hegemony in the eastern Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean after the defeat of the Ottomans at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571.

As European traders flooded the global market, they were quick to make alliances with local minorities involved in commerce.41 In Aleppo, these minorities consisted principally of Armenians, Maronites, Chaldeans, Jews, Catholics, Assyrians, and Greek Orthodox Christians. According to Masters, the Christian population in the seventeenth century constituted 20 percent of the city’s population. The close relationship between non-Muslims and foreign merchants in the city cannot be underestimated. Non-Muslim merchants were quick to form alliances with their European counterparts. At times, non-Muslim merchants were given citizenship by European countries that afforded them privileges usually offered to foreign merchants. This entitlement included capitulatory benefits such as protection, tax exemptions, and immunities (berat) that were offered to some Christians and Jews who were protégés of the various foreign consulates in Aleppo.

The northwest quadrant of the city was an important zone for several reasons. It hosted most of the non-Muslim neighborhoods such as Bab al-Nasr and Kharij (Outside) Bab al-Nasr, al-Bandara, and Bab al-Janayn (see map I.3). The southwest part of the city, on the other hand, was predominately Muslim.42 It is important to note that no neighborhood was exclusively Christian or Jewish, and neighborhoods were not segregated according to religion or even social class.43 The area outside of Bab al-Nasr, particularly the quarter of Saliba al-Judayda, was a predominately Christian neighborhood, and the quarters of al-Bandara, al-Masabin, and Bahsita were heavily populated by Jewish residents. The area of Bab al-Nasr happened to be the industrial zone of the city, with the highest concentration of workshops and artisans.44 This section of the city contained blacksmiths’ shops, wood merchants, and copper and brass foundries. The majority of the artisans were Christian, but there were some Muslim workers as well.45 The Bab al-Nasr region attracted the attention of foreign traders who did business and sometimes chose to live there. Traders who chose not to live there could be found in the caravansaries just south of Bab al-Nasr, close to the Central Market that extended between Antakya Gate and the citadel.

As much as these neighborhoods buzzed with daily business dealings, complaints of criminal activity were heard in the shari‘a courts. As demonstrated in court cases highlighted throughout later chapters, the court was accessed by Muslims and non-Muslims alike. In fact, cases involving only Christians and Jews were also brought to the shari‘a court for trial despite the fact that these communities had their own courts.46 The use of the shari‘a court by non-Muslims has been the topic of several histories in recent years.47 However, not unexpectedly, since the Muslims formed the overwhelming majority of the population, the majority of cases brought before the court involved Muslims alone.

The diverse range of participants in the courts has made the records an invaluable source for unearthing some of the history from below. The source can tell a scholar much about the elite Muslim families and wealthy non-Muslim merchants of the city. But the records also tell us something about the lives of Aleppo’s marginal poor, religious minorities, and women. Some schools of history, such as the French Annales school, have been able to create statistical studies from the records. I have used some of the data collected in this way, but I have done so with considerable caution. Since the collection of Aleppo court records is incomplete, it is not possible to determine exact quantities of any given group that appeared in court.

Throughout its history, Aleppo was periodically shaken by political and social power struggles. In the early seventeenth century there were several rebellions called the Jelali (meaning “rebel” or “outlaw”) Revolts that posed a serious threat to the empire. Although many of these revolts were based in Anatolia, Aleppo was also the scene of much fighting. One rebel leader, ‘Ali Canpulatoğlu, was a Kurd from a clan based in the small towns of Kilis and ‘Azaz, near Aleppo. The Canpulatoğlu were recognized as political bosses in the region by the Ottomans who attempted to integrate these local tribesmen within the empire in hopes of pacifying them. The result was a clash between the Kurdish clan and the Janissaries of Damascus who appeared “in 1603, as in 1599 and 1601 . . . pillaging and looting, while the Ottoman governor looked on from the security of the city’s citadel unable to restore order.” The Canpulatoğlu clan subdued the Janissaries and protected the city, and in return for this service the Ottomans granted Husayn, chief of the clan, the governorship of Aleppo. Soon afterward, in 1605, the Ottomans were at war with Iran and demanded Husayn’s assistance, but their army suffered a defeat before Husayn and his troops arrived. When Husayn heard the news of this defeat, his troops turned back and camped in Van. In return for his failure to defend the state when in need, the Ottoman general Çağalzade Sinan Paşa executed him.48 Husayn’s nephew ‘Ali then initiated another rebellion in revenge, and the Ottomans immediately granted him the position of governor in 1606 yet, at the same time, secretly prepared an army to attack him. The Ottoman army attacked him the following year, and ‘Ali’s forces were defeated. He was given a pardon and granted a position in Romania, but in 1610 he was found guilty of treason and executed. After this period of rebellion, the Ottoman authorities did not appoint locals to the governorship, with one exception, Ibrahim Agha Qattar Aghasi, who was appointed governor in 1799 and held the office for five years.49 He was an illiterate and relatively unknown member of the local notables (a‘yan) who had been a tax farmer in Aleppo. It was common for governors throughout the empire to buy their position from the Ottomans, which intensified the strong links of patronage to Istanbul.

Most often, the Ottomans rotated their officials in order to discourage the continuous contact necessary to build a power base, but it did not exclude other social groups from ascending to power, most notably the Janissaries. Local military commanders had been fighting each other since the late sixteenth century. The Janissaries had dominated the city and were eventually expelled in 1604, only to rebuild their power base in later years. The power of the Janissaries was also increasingly checked by a new rising force in the city, the dominance of the ashraf, nobility who traced their blood lineage to the Prophet Muhammad.

These power struggles took place in the context of a weakening economy. In 1619, the Ottoman economy was seriously affected by the Safavids’ attempt to create a monopoly on the silk trade by sending exports by sea instead of by land. It would have severely hurt the Ottoman economy, which partly depended on the revenues generated from transit taxes on the caravan trade.50 In fact, the Safavid monopoly was short-lived, and foreign traders resumed business in the Levant by 1629. Over the next century, foreign traders created closer links with the local economy of Aleppo, but eventually the decline in the demand for Middle Eastern silk, as a result of the opening up of new sources of supply, caused the merchants to look elsewhere. Other economic factors included cheaper textile production in France, which undermined the traditional trade relations between European merchants and Levantine textile manufacturers. Eventually, only raw materials were sought from Aleppo, and the caravan trade had greatly declined by 1750, which effectively cut out the middleman role of Aleppo’s merchants.51

The late eighteenth century was a period of increased political instability as several groups struggled for political ascendancy and challenged Ottoman authority. Three groups, the Janissaries, the ashraf (descendants of the Prophet Muhammad), and the Ottoman government, all competed for power in Aleppo.52 Ottoman attempts to install their own appointees as governors of the city were met with stiff resistance from both the Janissary garrison and the ashraf; allied against the Ottoman authorities, the two groups often rivaled each other. The eighteenth century also saw popular riots in a protest led by the ashraf against high bread prices and taxes in 1770. Soon after, in 1775, another riot, this time led by the Janissaries, was directed against the appointment of ‘Ali Pasha as governor, whose bad reputation had become known to the residents prior to his arrival. Ultimately, ‘Ali Pasha left Aleppo in humiliation. This banishment was not an unusual occurrence, as it happened again in 1787 with Governor ‘Uthman Pasha and in 1791 with Governor Kusa Mustafa Pasha, who were removed in popular protests orchestrated by the local ashraf and Janissaries. “Such resounding success of the two dominant groups of Aleppo no doubt explains why the Imperial Government several times attempted to crush their power.”53 Increased localism is demonstrated in the resulting short-lived dominance of the Janissaries between 1808 and 1812. During this period of Janissary rule, soldiers controlled quarters of the city, the guilds, and the city’s food supply. The Janissaries also robbed homes, extorted money, and broke into small businesses throughout the city.54 Another revolt in 1819 was not easily suppressed by the Ottomans. The Ottomans attempted to reassert direct control over Aleppo, but were also distracted by external events, particularly wars.

As much as the eighteenth century was dominated by internal tensions within the empire, it marked an intense period of warfare in which the Ottoman Empire struggled to defend its borders from rival powers. The Ottomans went to war with Iran in 1723 and again in 1746, and wars with the Russians and the Austrians (1768–74 and 1787–92) soon followed. This series of wars undermined the strength of the Janissaries and made way for a stronger ashraf in Aleppo. Wars continued to affect Ottoman borders as the empire lost control over Egypt after Napoleon’s invasion in 1798. The French controlled Egypt for only three years, but when they left the power vacuum was filled by the ambitious governor Muhammad ‘Ali, who had imperial ambitions of his own. He built an army and sent his son Ibrahim to invade the Ottoman lands to the east, conquering Palestine and Syria in 1831. Some of the policies initiated by the Egyptians included conscription and direct taxation. Egyptian rule over the Levant was characterized by the increased participation of non-Muslims in government, particularly in the administrative bodies (majlis) that the Egyptians set up in every town. They recruited members from among both Muslims and non-Muslims to be representatives within the majlis.55 The system was eventually dismantled after the British put an end to Muhammad ‘Ali’s threat to the Ottoman Empire in 1839, although the return to Ottoman rule after the Egyptian occupation proved particularly disruptive.

The Ottomans continued the system of conscription and taxation that the Egyptians had instituted. Furthermore, they attempted to ease the growing tensions between the Muslim and non-Muslim populations by initiating a period of reform. It was intended not only to reformulate the conception of the empire and of citizenship and nationality within it but also to centralize the empire—something that had fallen by the wayside since 1760.56 The first initiative, the 1839 Hatt-i Sharif of Gülhane, or the Imperial Rescript of the Rose Chamber, contained several areas of legal reform, one of which included Muslim and non-Muslim equality under the law.57 It marked a sharp departure from the previous millet (or zimmi) that characterized Muslim empires in the past. It was at this point that the Ottomans viewed their non-Muslim subjects as equal under the law, and subject, for example, to military service as their Muslim counterparts but also given rights to political participation in provincial councils.58 The edict was meant to appeal to Europe, but it was not fully accepted by the Ottoman public. It does mark a period of reform in the Ottoman Empire known as the Tanzimat (Reorganization) that would last until 1876. Events in Aleppo demonstrate the effects of these reforms. In 1850, just a decade after the proclamation of the Hatt-i Sharif, tensions between the Muslim and non-Muslim community in Aleppo resulted in riots, the culmination of increasing resentment toward Ottoman centralization and the legal reforms as well as economic hardship. The 1850 attacks were focused on both non-Muslims and Ottoman authorities.59

Such difficulties resulted in yet another edict, the Hatt-i Hümayun of 1856, reiterating the principles of the 1839 Hatt-i Sharif. Some of the reasons for the reissuing of the edict were diplomatic. The Ottomans had fought another war in the Crimean with the Russians (1853–56) and sought European favor through increased reforms, improving the quality of life for Christians within its realm. This period forever affected the relations between Muslims and non-Muslims. Non-Muslims were now legally equals, subjected to military service, and no longer required to pay the jizya (a poll tax paid by Christian and Jewish adult men to the Ottoman state). However, this period also had drastic effects on the legal system that had been in place for centuries. My study ends before the initiation of these changes in the court system, a topic discussed by other scholars.60 The reforms would result in a split in legal jurisdictions and the creation of several courts, including a nizami court for criminal matters in 1871. These records would have proved ideal for my study: alas, the records of the Aleppo nizami court have not so far been located.61