SECTION III

UPS AND DOWNS

15

Too Full of Myself

For chrissakes, Jack, what are you going to do next? Buy McDonald’s?”

The remark came from a foursome of guys across the seventh fairway at Augusta as I was teeing off from the third hole in April 1986. Four months after announcing the deal to buy RCA, I had just acquired Kidder, Peabody, one of Wall Street’s oldest investment banking firms.

While the guys were only kidding, there were others who really didn’t think much of our latest decision. At least three GE board members weren’t too keen on it, including two of the most experienced directors in the financial services business, Citibank Chairman Walt Wriston and J.P. Morgan President Lew Preston. Along with Andy Sigler, then Chairman of Champion International, they warned that the business was a lot different from our others.

“The talent goes up and down the elevators every day and can go in a heartbeat,” said Wriston. “All you’re buying is the furniture.”

At an April 1986 board meeting in Kansas City, I had argued for it—and unanimously swung the board my way.

It was a classic case of hubris. Flush from the success of our acquisitions of RCA in 1985 and Employers Reinsurance in 1984, I was on a roll. Frankly, I was just full of myself. While internally I was still searching for the right “feel” for the company, on the acquisition front I thought I could make anything work.

Soon, I’d realize that I had taken it one step too far.

Our logic for buying Kidder was simple. In the 1980s, leveraged buyouts (LBOs) were hot. GE Capital was already a big player in LBOs, helping to finance the acquisition of more than 75 companies in the prior three years, including one of the earlier successes of the LBO game—Bill Simon’s and Ray Chambers’s acquisition of Gibson Greeting Cards.

We were getting tired of putting up all of the money and taking all of the risk while watching the investment bankers walk away with huge up-front fees. We thought Kidder would give us first crack at more deals and access to new distribution without paying these big fees to another of Wall Street’s brokerage houses.

Eight months after closing the deal, we found out we had walked into one of the most public scandals ever to hit Wall Street. Marty Siegel, a Kidder star investment banker, admitted trading insider stock tips to Ivan Boesky in exchange for suitcases full of cash. He also admitted that Kidder had made trades based on information allegedly obtained from Richard Freeman at Goldman Sachs. He pleaded guilty to two felonies and cooperated with U.S. attorney Rudy Giuliani’s investigation.

As a result, armed federal deputies stormed into Kidder’s offices on February 12, 1987, at 10 Hanover Square in New York. They frisked, cuffed, and removed from the building the head of arbitrage, Richard Wigton. They also arrested another ex-Kidder arbitrageur, Tim Tabor, and Goldman’s Freeman for alleged insider trading. The charges against Wigton and Tabor would eventually be dismissed. Freeman would be sentenced to four months in prison and a $1 million fine.

Though the illegal trading occurred before GE acquired Kidder, as the new owners we got saddled with the legal responsibility. After the arrests, we began an investigation, cooperating fully with the SEC and Giuliani. It showed that there were lots of weaknesses in the firm’s control systems. Kidder chairman Ralph DeNunzio had nothing to do with the scandal, but it was clear Siegel had been given great latitude.

Siegel had complete run of the equity trading floor, and when he asked the risk arbs to make a trade, there were few questions. He also had a strange habit that would prove to be part of his downfall. He kept file drawers full of every pink telephone message slip he had ever received. With those slips and Kidder’s detailed phone records, it wasn’t hard to establish a pattern to Siegel’s trading.

Giuliani, who could have gotten Kidder’s licenses suspended and put it out of business, wanted us to dismiss much of the senior management. Larry Bossidy, then a GE vice chairman, spent a couple of Saturday mornings with Giuliani negotiating a settlement. We ended up paying fines of $26 million, shutting down Kidder’s risk arbitrage department, and agreeing to put in better controls and procedures. While all that was going on, Ralph DeNunzio and several of his key people decided to leave.

As far as senior management was concerned, this left us with little more than the furniture Wriston warned us about. We had to go out and find someone who could build back the trust in the company. I thought Si Cathcart was the perfect choice. He was savvy, honest, and someone I trusted completely. Si had been on the GE board for 15 years and had been chairman of Illinois Tool Works.

When I called him in Chicago and told him about my idea for him to run Kidder, his first reaction was not exactly encouraging.

“Are you out of your cotton-pickin’ mind?” he asked.

“Si, just listen. I’ll come out there or you come to New York and we’ll have a good discussion about it.”

A few days later in March, Larry Bossidy and I met him in a small Italian restaurant in New York. Si showed up with a sheet of yellow legal paper with 15 reasons why it was a bad idea. He had the names of half a dozen people he thought would be better for the job. I looked over his notes and crumpled them up.

“Si, we’ve got a real problem and you’re the only guy who can help us,” I said. “We have to stabilize things and get Kidder back on a recovery path. The job won’t last much more than a couple of years. You and Corky will have a great experience in New York. You’re too young to retire.”

I probably said a lot more. Larry and I really needed him. Si finally agreed to go home and talk it over with his wife, Corky. Fortunately, she was excited about coming to New York and Si wanted to help us. He called back in a couple of days and agreed to accept the job.

On May 14, the day after Giuliani dismissed indictments against Wigton and Tabor, Si took over as CEO and president of Kidder. Larry Bossidy announced the change on Kidder’s interoffice squawk box at 10 A.M. sharp. Not everyone was ecstatic. The Wall Street Journal article quoted an unnamed Kidder official: “Just what we need, a good tool and die man.”

One of the problems was that Marty Siegel was not simply another guy who took the money and caused the scandal. He was Kidder’s star. Good-looking, smooth-talking, and the highest-paid employee in the place, he was one of the leading investment bankers on Wall Street.

The media called Siegel “the Kidder franchise.” Many of Kidder’s traders idolized and worshiped the guy. For pleading guilty to two counts of insider trading, Siegel paid $9 million in fines and was sentenced to two months in prison and probation. Why, with all he had going for himself, he got involved with Boesky and bags of money was beyond anyone’s comprehension.

Many of Kidder’s employees lived off Siegel’s franchise. Losing it sank the morale in the rest of the firm. As Si dug into things, he found that it wasn’t very pretty. When he asked about purchasing—a question someone from manufacturing might ask—no one knew who ran the department or where it was. The bonus system was ad hoc. Ralph would sit down with the top people in the firm and negotiate one by one their year-end bonuses.

Frankly, the bonus numbers knocked most of us off our pins when we saw them. At the time, GE’s total bonus pool was just under $100 million a year for a company making $4 billion in profit. Kidder’s bonus pool was actually higher—at $140 million—for a company that was earning only one-twentieth of our income.

Si remembers that on the day Kidder employees got their bonus checks, the place would clear out in an hour. “You could shoot a cannon off without hitting anyone,” he told me. Most of them lived a lifestyle dependent on those annual bonuses. It was a different world from what Si or I knew.

When Si went through his first bonus exercise, he’d ask everyone at Kidder to give him a list of his or her accomplishments for the year. Inevitably, he’d have six people claiming credit for being the key player on the same deal. Every one of them believed they made the deal happen. The attitudes were symbolic of the problem: an entitlement culture where every player overvalued themselves.

Where God parachutes us is a matter of luck. Nowhere is that more true than Wall Street. There are more mediocre people making more money on Wall Street than any other place on earth. Sure, there are some stars, and some earn every nickel they make. The crowd they carry along with them is something else. Wall Street might be the only place in the world where a $100,000 raise is considered a tip.

When you handed someone a check for $10 million, they’d look you in the eye and say, “Ten? The guy down the street just got 12!” “Thank you” was a rare expression at Kidder.

The outrageous pay in a good year was bad enough. It really drove me nuts in a bad year. That’s when the argument would go something like this: “Yeah, we had a tough year, but you’ve got to give them at least as much as they made last year or they’ll go across the street.”

This place had the perfect we-win, you-lose game.

Wall Street had to have been better when the companies were private and the partners were playing with their own money rather than “other people’s money.” The concept of idea sharing and team play was completely foreign. If you were in investment banking or trading and your group had a good year, it didn’t matter what happened to the firm overall. They wanted theirs.

It’s a place where the lifeboats carrying millionaires were always going to make it to shore while the Titanic sank.

Si’s stay at Kidder was tough. He put in better controls and hired some good people. Five months into the job, in October 1987, the stock market crashed. Kidder’s trading profits disappeared. Kidder losses hit $72 million that year, and we had to lay off about 1,000 of the 5,000 people on the payroll.

It was obvious to all of us that the cultural differences between Kidder and GE were so great that I should have listened to the dissenters on my board. I wanted out, but was looking for a way to do it without losing our shirt. I hoped to show some results before selling the business.

Si wanted out, too. He had a steadying influence on the place, but after two years in the job, he felt that Kidder needed a permanent leader. We hired a search firm to look for Si’s replacement. We couldn’t get one.

Larry and I asked an old friend, Mike Carpenter, then an executive vice president at GE Capital, if he would run Kidder. Larry, Dennis, and I had met Mike in late 1980 when we were trying to acquire TransUnion, a Chicago-based railcar lessor. We lost the deal to Bob and Jay Pritzker but got to know Mike, who was then with the Boston Consulting Group and had recently completed a strategic analysis of TransUnion.

I hired him in 1983 as business development leader for GE. Mike was a big player in the RCA deal and was doing a great job at GE Capital, where he had responsibility for our LBO business. He wanted to run his own show and agreed in February 1989 to take on what he knew was a very tough assignment at Kidder.

Si stayed for several months, helping Mike in the transition. Mike continued Si’s efforts to make integrity a key value of the place. He also developed a well-defined strategy for each of Kidder’s businesses. Profits recovered, and Kidder went from losing $32 million in 1990 to making $40 million in 1991 and $170 million in 1992.

We still wanted out and started conversations with Sandy Weill of Primerica. We came very close to striking a deal that would have gotten us out whole. But it fell apart over the 1993 Memorial Day holiday. Sandy and I had a general agreement on Friday of that weekend. We all felt that on Wall Street, you had to make the deal fast, over a weekend if possible before the news leaked, or you’d quickly lose the employees and get slaughtered. Dennis Dammerman, then chief financial officer, negotiated the fine print over the weekend, staying in touch with me in Nantucket by phone.

I expected to return on Memorial Day to wrap it up with Sandy.

It didn’t work out that way. By the time I returned it was obvious that we weren’t going to get the deal we started with. Sandy has done one of the great jobs in American business by building an enterprise through great acquisitions. I’m one of his biggest fans. But it was a challenge negotiating with him. By Monday, the deal that was going to get us out whole had been scratched, clawed, and picked at so that it was unrecognizable.

I spent a few hours that evening trying to get it back to where it had been. After a couple of tries, I saw it was hopeless and walked down the hall and told Sandy, “This deal is not for us.” He smiled. We shook hands and have remained friends.

After the Primerica deal collapsed, Mike went back to work and we stayed out of the spotlight. Profits reached $240 million in 1993, and things appeared to have stabilized—or at least I thought they had.

I was getting ready to leave the office for a long weekend on Thursday night, April 14, 1994, when Mike called with one of those phone calls you never want to get.

“We’ve got a problem, Jack,” he said. “We have a $350 million hole in a trader’s account that we can’t identify, and he’s disappeared.”

I didn’t yet know who Joseph Jett was, but over the next few days I would learn more than I cared to about him. Carpenter told me that Jett, who ran the firm’s government bond desk, had made a series of fictitious trades to inflate his own bonus. The phony trades artificially boosted Kidder’s reported income. To clean up the mess, we would have to take what looked like a $350 million charge against our first quarter earnings.

The news from Mike made me sick: $350 million, I couldn’t believe it.

It was overwhelming. I rushed to the bathroom, and my stomach emptied in awful spasms. I called Jane, who was already waiting for me at the airport, told her what I knew, and asked her to come home instead. That evening I called Dennis Dammerman, who was teaching at Crotonville.

When he came to the phone, I told him: “It’s your worst nightmare.”

Actually, it was my own worst nightmare. I had made a terrible mistake in buying Kidder in the first place. It had been nothing but a headache and an embarrassment from the start—and now this.

Dennis went down to Kidder’s offices with a team of eight others and began working around the clock throughout the weekend. I couldn’t do much because they were doing gritty audit work, checking account balances. I sat by the phone, waiting for updates from Dennis. If I had gone down there, I probably would have driven them nuts.

By Sunday afternoon, I had to see it for myself. When I did, Dennis and Mike said they were sure the paper entries reported as earnings were bogus. We didn’t have all the facts, but with our first quarter earnings release two days away, they were convinced we had a $350 million noncash write-off to deal with.

I spent hours trying to figure out exactly how hundreds of millions of dollars could disappear overnight. It didn’t seem possible. We obviously didn’t know enough about the business. We’d later discover that Jett had taken advantage of a flaw in Kidder’s computer systems.

That Sunday evening, I called 14 of GE’s business leaders to deliver the bad news and apologize to each of them for what had happened. I felt terrible, because this surprise would hit the stock and hurt every GE employee.

I blamed myself for the disaster.

The previous year, 1993, when Jett’s phantom trades accounted for nearly a quarter of the profits made by Kidder’s fixed income group, Jett had been named Kidder’s “Man of the Year.” We had approved Mike’s request to give Jett a $9 million cash bonus, a huge award even for Kidder. Normally, I would have been all over this. I would have dug into how one person could be so successful, and I would have insisted on meeting him. I didn’t.

It was my fault because I didn’t ask the “why” questions I normally did. It turned out that Kidder was as culturally distant from us as GE appeared to the Kidder employees.

The response of our business leaders to the crisis was typical of the GE culture. Even though the books had closed on the quarter, many immediately offered to pitch in to cover the Kidder gap. Some said they could find an extra $10 million, $20 million, and even $30 million from their businesses to offset the surprise. Though it was too late, their willingness to help was a dramatic contrast to the excuses I had been hearing from the Kidder people.

Instead of pitching in, they complained about how this disaster was going to affect their incomes. “This is going to ruin everything,” one said. “Our bonus is down the toilet. How will we keep anyone?” The two cultures and their differences never stood out so clearly in my mind. All I heard was, “I didn’t do it. I never saw it. I never met with him. I didn’t talk to him.” No one seemed to know anyone or work for anyone.

It was disgusting.

We fired Jett and reassigned six other employees that night. When I got home later, I told Jane to hunker down. We were going to go through a very long and very tough ride.

“The media’s going to come after me. Just hang on.”

The coverage was brutal. Again, I went from prince to pig. In the space of a year, we ended up in the right-hand column of the front page of The Wall Street Journal numerous times. Time magazine had a new moniker for me: “Jack in the Box.” A Newsweek writer claimed that “you can hear the sound of the pedestal cracking.”

A cover story in Fortune on the disaster jumped to the ridiculous conclusion that the scandals at Kidder were brought on by poor GE management. It was BS. The problem at Kidder was confined to Kidder. It was all about having a bad apple and insufficient controls.

The internal investigation of what went wrong at Kidder was led by Gary Lynch, a former SEC enforcement chief who was now with Davis Polk & Wardwell. With enormous help from GE’s audit staff, he found that the oversight of Jett’s trades was a big part of the problem. Lynch reported that time and again questions raised about the unusual trading profits were “answered incorrectly, ignored, or evaded. . . . As his profitability increased, skepticism about Jett’s activities was often dismissed or unspoken.”

At Kidder, the fixed income group had become the franchise, earning more than the firm earned in total. When they spoke, the firm listened, and few questioned the basis for their success. We weren’t the first on Wall Street to learn this lesson. Michael Milken and Drexel Burnham was the most vivid example, but even terrific leaders like Frank Zarb and Pete Peterson struggled with the dominance of trading at Lehman Brothers. The lesson was there to be heard. We hadn’t listened.

Later, an SEC administrative law judge found that Jett had acted “egregiously” in committing fraud on Kidder. Judge Carol Fox Foelak found that Jett had intentionally deceived his supervisors, auditors, and others with false denials and misleading and conflicting explanations. She barred Jett from association with any broker dealer and ordered him to pay $8.4 million in penalties.

Kidder cost us years of trouble and some of our best executive talent. By mid-June of 1994, I had to ask my friend Mike Carpenter to leave his job. That was about the hardest decision I ever had to make. Mike was a great executive, who had attacked the Jett problem—one he didn’t create.

He was a bigger victim of the scandal than anyone. The media wanted his hide, and until they got it the negative coverage would never end. He and I had a long conversation, which I concluded by saying, “This isn’t going away until you go.” He understood and was a class act. Jett’s immediate boss, Ed Cerullo, the head of the fixed income area at Kidder, left a few weeks after Mike.

In Mike’s place, we temporarily moved Dennis Dammerman to Kidder as chairman and CEO and Denis Nayden, another smart GE Capital veteran, as president and chief operating officer.

Four months later, in October 1994, we finally struck a deal to sell Kidder for $670 million plus a 24 percent stake in PaineWebber. Once again, Pete Peterson played an important role. Negotiations between GE Capital and PaineWebber CEO Don Marron had broken down over a weekend in early October.

I called Don to see if we could put things back together again. Don called in Pete, a longtime friend of his, as an adviser on the deal. Don and I knew each other only vaguely, so Pete became the key player in the negotiations. Pete, Don, Dennis, and I quickly reached a general agreement and shook hands. I left for a ten-day Asian business trip, and Dennis did the final negotiation. Pete called me a couple of times, once I remember at 3 A.M. in Thailand, to work out a couple of stumbling blocks.

The deal was concluded in about ten days, and the friendship among the four of us has never wavered.

The story has a somewhat happy ending. Late on a Friday in mid-2000, Pete called me just as I was about to leave the office.

“Jack, I’m sorry to bother you,” he said, “but I wanted to make your weekend for you.”

Pete said that he and Don had reached an agreement to sell Paine Webber to Swiss bank UBS for $10.8 billion. “We just made over $2 billion for you, and I hope you’ll go along.”

“Make my frigging weekend?” I shouted. “You made my whole frigging year!”

Don, his team, and several key Kidder players made the merger a great success. That success gave us an eventual after-tax return of 10 percent a year over the 14 years from the purchase of Kidder to the sale of Paine Webber. By no means was it a financial success, but the outcome was better than a few others.

However, there’s no amount of money that would make us want to go through that again.

The Kidder experience never left me. Culture does count, big time. During the dot.com craze of the late 1990s, several people in the GE Capital equity group were enjoying success—not unlike day traders in their living rooms. These folks decided they would stay with GE only if they got a piece of the equity in the deals they were investing GE money in.

I told them to take a hike. A few did, and the media gave us some heat, claiming we were “not with it.” We didn’t get the New Economy. “Absolutely!”

It gave me another chance at the officers meeting in October to make the point that at GE there is only one currency: GE stock (below). There are different amounts of it for different levels of performance, but everyone’s life raft is tied to the same boat. One culture, one set of values, one currency, doesn’t mean, however, one style—every GE business has its own personality.

For the same reason—a big culture gap—I’ve passed up opportunities to acquire high-tech companies in Silicon Valley that appeared to be a good strategic fit. I didn’t want to pollute GE with the cultures that were developing there in the late 1990s. Culture and values count too much.

There’s only a razor’s edge between self-confidence and hubris. This time, hubris won and taught me a lesson I’d never forget.

16

GE Capital: The Growth Engine

One night in June 1998, I was sitting on the couch at home, leafing through the “deal book” for the next day’s GE Capital board meeting. One of the ideas up for approval struck me as one of the wackiest I had seen in my 20 years on the board.

The proposal was to buy $1.1 billion of auto loans in Thailand from a group of failed finance companies that had been seized by the government. I knew the country was in the worst recession in its history, and we were the only auto finance company still standing.

I quickly explained the deal to Jane, who was sitting across from me.

“The guy making this pitch won’t even get to sit down,” I told her. “We’ll blow him out of the meeting in five minutes or less.”

These sessions aren’t your run-of-the-mill board meetings. We finance billions of enterprises yearly, and potential deals are put through a monthly torture chamber. The meetings are hands-on, no-holds-barred discussions among some 20 GE insiders with more than 400 years of diverse business experience.

This crowd has looked at and torn apart literally thousands of deals before we make a decision. Although all the proposals have been rigorously prescreened before they hit the board—and 90 percent of the proposals eventually get approved—we still send back one in five for another look.

When I read the details on the Thai deal that night, I was convinced this one was headed for the Dumpster. The proposal, a 50/50 partnership with Goldman Sachs, would make us the owner of one of every nine cars in Thailand. To pull it off, we’d have to hire 1,000 extra employees in the country to underwrite the loans, collect the payments, and manage the disposition of any repossessed cars. If our bid was accepted, we’d take over the loans for 45 percent of their face value. The idea had come from Mark Norbom, who headed up GE Capital’s business in Thailand.

The next morning, I walked into the meeting in Fairfield with a smile on my face.

“Thai auto loans?” I said, laughing. “I can hardly wait to get to that one.”

When I turned the page to Mark’s proposal, I frowned and shook my head.

“How could we possibly hire and train those 1,000 people within a few months?” I asked.

Mark’s answer impressed me. He said his team had already screened 4,000 job candidates, interviewed more than 2,000, and issued 1,000 contracts contingent on winning the bid. He told us that a car is among the most prized possessions in Thailand. People would give up almost everything else—would even sleep in their cars—before losing them for nonpayment of a loan.

After a bit of banter and a passionate pitch from Mark, we bought it. Talk about changing your mind on something because of a good presentation and a lot of passion. That was as good an example as I could remember.

I walked into that meeting thinking, This guy’s outta here, and I walked out thinking, Isn’t this neat?

Mark was right. Over the next three years, GE has done well, and the company built an ongoing and profitable auto business in Thailand. The transaction led to several other troubled asset purchases in Asia, all of which panned out well for GE and the local economies.

Mark did okay, too. He became president of GE Japan.

The small Thai deal was one of thousands that show how GE Capital, once a popcorn stand, has become one of the most valuable parts of GE. When I got my first look at the business as a sector executive in 1978, GE Capital earned $67 million on $5 billion in assets. (In 2000, GE Capital made $5.2 billion, 41 percent of GE’s total income, on more than $370 billion in assets.)

The story of that phenomenal growth has been told many times and in many ways. What most people outside GE don’t know is the incredible intensity, ingenuity, and entrepreneurship that goes on behind that success.

What I saw in 1978 was immense opportunity—not just the benefit you get on a balance sheet, but the additional leverage you get by putting together two raw materials: money and brains.

Since I had been involved in making things all my life, pounding and grinding it out to make a nickel, I couldn’t believe how easy this “appeared” to be. The business already demonstrated there were terrific deals with good collateral that could produce remarkable returns on equity. One example: Leveraged leases on aircraft could earn 30 percent or better returns.

I fell in love with the idea of melding the discipline and the cash flows from manufacturing with financial ingenuity to build a great business. Of course, we needed the right people to make this happen.

Dennis Dammerman would always remind me of Ben Franklin’s old adage, “You don’t earn interest unless you collect the principal.” Fortunately, GE Capital already had a culture that insisted the people making the deals stayed with them from womb to tomb. If you pitched a deal, you’d better make damn sure it was going to work. Or else you’d better be able to take over the asset and make it work yourself.

I was sure the opportunity was enormous. All we had to do was take the business from the back of the boat to the front. Better people and a greater financial commitment could lead to huge profits.

Happily, I found Larry Bossidy playing Ping-Pong. Larry, along with GE Capital CEO John Stanger, was the guy who shook the place up. From our game in Hawaii, I understood his frustration. In 1978, GE Credit was an orphan business, outside the mainstream of the company. Plastics, too, had been an orphan business during my earlier days there. Larry wanted to put GE Capital up on center stage. A former auditor, he came from deep inside GE Capital, and he knew what had to be done.

The first big move I made at GE Capital was to get Reg’s approval to make Larry chief operating officer in 1979. Larry, like me, was not a picture-perfect GE executive. No model of sartorial splendor, Larry could always be recognized from the back because his shirttail flew in the wind. His idea of a summer suit was to take his winter suit and dress it up with a white belt and shiny white patent-leather shoes. (With his increasing prominence in the business world, Larry’s now become GQ cover material.)

He has always been a remarkable family man. His wife, Nancy, did a fantastic job raising their nine kids. Larry helped but often worked late nights and weekends. Three of their children came to work for GE, including Paul, who now runs commercial equipment finance with $38 billion in assets, one of our top 20 GE businesses.

Larry and I thought along the same lines on a lot of things, nowhere more so than on the people front. Not only did we have Session Cs to look closely at people, but we had the monthly board reviews where we held their feet to the flame. We saw people under real fire, pitching deals every month—and in some cases, explaining later how they’d work their way out of trouble.

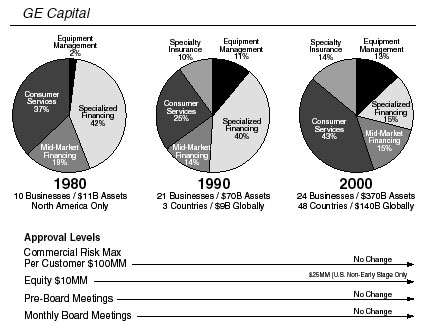

Over my 23-year involvement with GE Capital, I saw the growth develop in four distinct stages: from 1977 to 1985, CEO John Stanger and Larry Bossidy lured some of the best people we had into GE Capital. In the second half of the 1980s, Bossidy (by then a vice chairman) and CEO Gary Wendt began to aggressively grow the business by making GE Capital an acquisition machine.

Through the 1990s, Wendt and operating chief Denis Nayden created a global financial services business by leading a decade of unprecedented deal making. The current team of Denis as CEO and Mike Neal as COO is expanding that global franchise and bringing to financial services the rigor of Six Sigma and digitization.

Looking back over the years of uninterrupted double-digit growth, it almost seems surreal. I can still remember when I stewed and stewed over a $90 million GE Capital deal. Compared to those Thai auto loans and the billions of dollars we might commit in a board meeting today, this was insignificant—but not back in 1982.

That’s when Larry Bossidy, Dennis Dammerman, and I were at a GE Capital management meeting in Puerto Rico, debating whether we should acquire American Mortgage Insurance from Baldwin United. We were just about dying over the deal—then GE Capital’s largest ever—mulling over how much to bid and worrying about every potential complication.

It’s a matter of perspective. Before we decided to buy American Mortgage in 1983, Dennis was literally signing every insurance policy we issued because his insurance business was so small that he couldn’t justify the purchase of a signature machine. After the deal, we not only could buy the machine, we became a major player in the business.

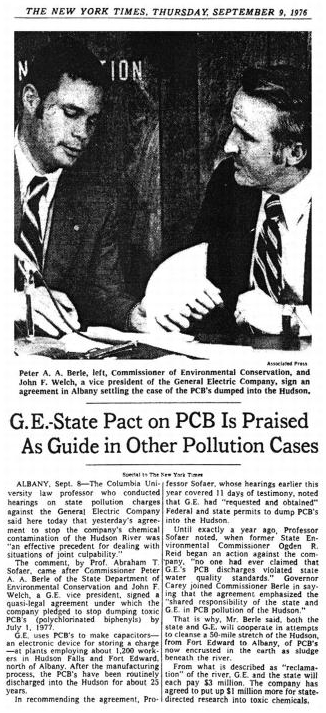

A year later, in 1984, we topped the little $90 million deal with our $1.1 billion acquisition of Employers Reinsurance Corp. (ERC). John Stanger and Dennis Dammerman first looked at ERC, one of the three largest property and casualty reinsurance companies in the United States, in 1979. The insurer asked us to be a white knight to fend off an unwanted bid from Connecticut General Insurance. At the time, our insurance assets were pretty small. ERC preferred us as a parent over Connecticut General, which obviously was a big player in the industry.

But, ERC went with their definition of a perfect white knight, a company that knew absolutely nothing about insurance: Getty Oil. In one of the most notorious deals of the decade, Getty was eventually acquired by Texaco, which had little use for a reinsurance company. With the background work done years earlier, we were able to move quickly to bring ERC into the fold. I negotiated the final details of the $1.1 billion deal with Texaco CEO John McKinley.

We were still puny operators in those days. When the ERC team came to Fairfield for Sunday night dinner after the deal, they told us they were going to fall short of the annual earnings forecasts assumed in the transaction.

I immediately wanted a discount on the price. My friend John Weinberg of Goldman Sachs had represented us in the acquisition. I phoned him at Augusta, pulled him off the golf course, and ranted about the earnings shortfall. I told him to call McKinley to get an adjustment on the price.

Fortunately, McKinley was a gentleman, accepted the new numbers, and gave us a $25 million discount. We ended up paying $1.075 billion. It makes me feel a little embarrassed today to have done that, but I was relatively new in the job and probably a bit too competitive for my own good.

The ERC acquisition was a big leap forward. We had a great run in ERC, growing net income from $100 million in 1985 to a peak of $790 million in 1998, until tough pricing and a rash of storms in 1998 and 1999 derailed us. We earned only $500 million in 2000.

We made Ron Pressman CEO to get it back on track. A former auditor, Ron had built a highly profitable real estate business and had just the right mix of smarts and discipline. Pricing is better, Six Sigma is taking hold, and if the weather cooperates, Ron will make this business hum again.

Most of what we did in the 1980s, we did in small steps. One of the hallmarks of GE Capital has been a “walk before running approach” to the markets. Before diving into a specific market, we tiptoed into the water.

We never had a great strategic vision for GE Capital.

We didn’t have to be No. 1 or No. 2. The markets were enormous. All we needed to do was couple GE’s balance sheet with GE brains to grow.

In the 1970s, the focus was on traditional consumer lending like mortgages and auto leasing, with some transportation and real estate investments.

In the 1980s, our focus shifted to stronger growth while maintaining tight control of risk. We didn’t change the conservative risk profile that existed in the seventies. What we did was hire unique people. We set them free to find the ideas, make the case to invest in their ideas, and grow.

Grow we did, as deals came from everywhere. Over the past 20 years, GE Capital exploded into a host of equipment management businesses from trucks and railcars to airplanes. We jumped on private-label credit cards. We became more aggressive in real estate. We went from half a dozen financial niches in 1977 to 28 different GE Capital businesses by 2001.

If ever there was a lesson that people made the difference, this was it. Over the years, we had a murderers row of talent—Larry Bossidy, Dennis Dammerman, Norm Blake, Bob Wright, Gary Wendt, and Denis Nayden. Every one of them would go on to become CEOs inside or outside the company.

A perfect example of homegrown success was Denis Nayden, who started right out of the University of Connecticut in 1977 as marketing administrator for air-rail financing. Over the next two decades, he moved up the ladder to become Wendt’s right-hand man until being named CEO in 1998.

We used talent from our industrial businesses to turn GE Capital from a pure financial house into a business with deal making as well as operational skills. Half of the current top leadership at GE Capital Services grew up on the industrial side.

Our managers knew how to run businesses. When a deal went sour, we rarely put a line through it. We hated write-offs. Instead, we took it over and ran it ourselves. We had the operational capability that let us stick with a tough asset.

When a loan to Tiger International went bad in 1983, we stepped in and became a railcar leasing company. When some of our passenger planes came off lease into a soft market, we converted the planes to cargo carriers and launched Polar Air, an independent cargo line. Our long experience in aircraft leasing led to the purchase of Polaris and the expansion of our business with Irish-based Guinness Peat Aviation’s assets in 1993 and 1994.

Today, GE Capital Aviation Services (GECAS) manages $18 billion in assets.

We built GE Capital deal by deal—big or small—with the great majority of the deals coming before our monthly board meetings. The company was always careful about the bets it made in financial services. I didn’t add any new discipline to the GE Capital risk process from the 1970s—but I didn’t lessen the discipline, either. Any equity deal involving more than $10 million and any commercial risk per customer over $100 million had to be brought before the board.

We never changed the approval levels as we grew.

I was in on just about every one of these transactions, so I share credit for the good decisions and blame for the bad ones. We did get into the leveraged buyout craze in the 1980s. In one LBO deal, we financed the buyout of Patrick Media, an advertising billboard company, in 1989. The business had decent cash flows and reasonable growth rates. Only one thing bothered me. Patrick was being sold by John Kluge, head of Metromedia and a famous deal maker.

I didn’t know much about billboards, but I knew that when John Kluge was selling, I shouldn’t be buying. I had met John during my days negotiating the Cox deal. I liked him a lot, but I also knew he was one of the savviest investors around. I should have followed my instincts and walked away. When billboard use hit bottom in the late 1980s, we took ownership of the company to avoid a $650 million write-off. We rebuilt the business, eventually earning a modest gain on its sale in 1995.

We also did an LBO of Montgomery Ward in 1988. It was almost a home run. Our 50/50 partner, Bernie Brennan, made the Forbes 400 as one of the richest men in the world, and Wards flourished. The retailer later hit a wall. Despite the valiant efforts of a new management team, Wards went through hell and eventually went bankrupt in 2000.

However, the good deals far outweighed the bad, and their range was extraordinary. For instance, we went into auto auctions. I had liked the business and had seen it at Cox Broadcasting during the failed negotiations in 1980. Cox owned Manheim, the leader in auto auctions. It was a pure service opportunity with low investment and high margins. Ed Stewart, who then ran auto leasing, began buying little auction companies in the early 1980s. Ed eventually bought more than 20 auto auction companies and formed an 80/20 joint venture with Ford Motor.

An auction was like going to a flea market, set up on grounds with wooden bleachers. Roving vendors sold hot dogs and beans and Harley-Davidson leather belts from the stands. Auctioneers were selling off used cars one a minute. In the end, Manheim was also the reason we sold the business. They were much bigger than we were and had the opportunity to consolidate the industry. We took the gain and sold to Manheim in the early 1990s.

Many of the best deals before the board—and some of the wildest—came from Gary Wendt, who led GE Capital’s strong growth as CEO from 1986 until 1998. The deals he pitched were imaginative and creative. Gary was not just a brilliant deal guy, he also had the rare ability to tell you what it would take to make a good deal out of a not-so-good deal.

Gary was a trained engineer, a Harvard MBA, and a natural negotiator. He was doing workouts at a real estate investment trust in Florida when he was recruited to GE Credit as manager of real estate financing in 1975. Later, he oversaw all commercial finance dealings, becoming chief operating officer of GE Capital in 1984. When Bob Wright left as GE Capital’s CEO to run NBC in mid-1986, Larry Bossidy put Gary Wendt in charge. Gary and Larry continued to work together to build GE Capital.

By 1991, Larry wanted to run his own show. He was 55 and a vice chairman, yet he couldn’t really go any higher at GE because I still had ten years in front of me as CEO. Larry wanted a chance to run a large company, and he got it through Gerry Roche, the headhunter at Heidrick & Struggles.

On a Monday morning in late June, Larry came into my office with the news.

“Jack,” he said, “you know the time has come for me to move on. I don’t want to sit here for the rest of my career. Something’s come up, and I’m going to take it.”

“When are you going to do it?” I asked.

“It will be announced tomorrow.”

“So you’ve made up your mind?” I asked.

“Yep. I’ve just got to do it,” he said.

It was an emotional meeting. We went way back, from the time in 1978 when we played Ping-Pong together in Hawaii and I convinced him to stay at GE. A lot of tears fell, and we hugged each other.

Then Larry told me he was going to become CEO of AlliedSignal, the industrial products company in New Jersey.

Larry said AlliedSignal appealed to him because it was a turnaround situation and it was located in the Northeast so he wouldn’t have to move his family.

When Roche called me later, I said, “Gerry, half my face is crying because you’re taking away my best friend and my best guy. The other half is smiling because he can run any company in this country and he deserves to run his own show.”

In the 1990s, Gary Wendt wanted to plant a flag everywhere he went. He told his team not to worry about a few wounds. “We’re going to win the war,” he said. “You’ve got to take ground.”

While every business took on globalization, no one practiced it more effectively than GE Capital. With Europe in a slump, Gary led a massive effort there. In 1994, Gary and his team picked up $12 billion in assets, more than half offshore. In 1995, they more than doubled the pace, acquiring $25 billion in assets, with $18 billion outside the United States.

GE Capital was on a global roll, acquiring consumer loan companies, private-label credit operations, and leasing operations for truck trailers and railcars.

The stories behind many of these deals are enough to fill volumes. One summer, during his vacation in 1995, Gary and his head of business development for Europe, Christopher Mackenzie, drove a van through eastern Europe. An idea machine, Christopher was Gary’s deal finder. They came back energized to do all kinds of deals in that part of the world. They also had in hand a proposal to buy a bank in Budapest. We liked Hungary and the bank fit nicely with GE Lighting, already there as a major employer in the country.

We also bought banks in Poland and the Czech Republic and used them to move into personal finance in those markets. The Czech bank deal had a funny twist because the bank’s owner also had an appliance distribution company and a warehouse loaded with Russian TVs. We agreed to the deal after being assured we wouldn’t get stuck with this Czech appliance business.

All three banks today are modestly profitable, throwing off about $36 million in annual net profits. Gary’s road trip is still paying off.

Another funny one was the time Dave Nissen, CEO of global consumer finance, set the stage for a pitch on buying Pet Protect, the second largest British company selling life and health insurance for cats and dogs. This one fell into the Thai auto loan category, appearing to be dead on arrival.

Dave began his presentation in 1996 with the words, “This dog will hunt.”

I didn’t know much about the market for pet insurance. We found out the business was growing by 30 percent a year with annual premiums of $90 million. The U.K. market ranked second only to Sweden in the percentage of cats and dogs insured, 5 percent versus 17 percent, so there was plenty of upside.

Jim Bunt, a GE Capital board member and treasurer, had a lot of fun with this one. In his review of the deal, Jim joked that the principal product coverage included “kennel costs if the dog owner was suddenly hospitalized,” but not “catastrophic loss due to dog bites.”

We gave the okay not because we knew pet insurance, but because we trusted the guys making the pitch.

With a price tag of $23 million, this deal was also a little one. There were many other bigger ones that raised serious questions. One time, in 1997, Nissen was pitching a deal to buy Bank Aufina, the consumer finance unit of a large bank in Switzerland. I balked.

Swiss bankers owned the banking world. Why would they agree to sell anything that would actually be any good? It didn’t compute. Nissen explained that Swiss bankers are real bankers who prefer the bigger deals and were more interested in global investment banking. A personal loan and auto financing business was a diversion.

We ended up buying two companies in Switzerland. In 2001, they made $78 million.

These deals were part of a grand plan by Nissen to build a global consumer finance company. The first big one, giving GE Capital a major European presence, was our acquisition in 1990 of the private-label credit card operations of the Burton Group, Britain’s largest clothing retailer. The next year, Dave added Harrods and House of Fraser.

During the difficult negotiations for this deal, the head of Harrods had a demanding and unusual negotiating style. When he didn’t like the way things were going, he’d leave the room and tell the guys that he’d be back in five minutes and wanted a better answer. After the tenth time he pulled the ploy, Nissen and his team made up cards with big block letters that spelled “SCREW YOU.”

When the head of Harrods came back into the room, the guys held up the letters. He got a kick out of it, and the humor took a lot of the tension out of the negotiations. They soon closed the deal.

While Gary and Denis were driving global growth, a lot was going on here in the United States. Some of the more interesting deals were being brought in by Mike Gaudino, head of commercial finance. While I looked every day at companies I wanted to buy, Mike looks at companies he wants to save. He always points out that more than half the companies in the United States are non-investment grade. Mike comes into the board six to seven times every year with troubled companies already in or often headed for bankruptcy. Along with judging the company’s leadership, Mike digs into our ability to recover the receivables and inventories. It’s an upside-down look at a business—the opposite of what we’re used to.

A good example is Eatons, a large retail chain in Canada that experienced financial difficulty in 1997. When other lenders wouldn’t provide financing, Mike sought approval for $300 million in loans to help the retailer out of bankruptcy. After another downturn, however, the company ultimately had to be liquidated. Mike managed to get back every penny of our investment and all of our projected returns. By working out dilemmas, like Eatons, Mike built great credibility. He’s had only one deal out of more than 200 turned down in the past six years. Mike’s upside-down approach coupled with strong underwriting has taken the business from breakeven in 1993 to close to $300 million in net income in 2000.

Gary Wendt became the high priest of growth inside GE Capital. He made business development a key part of its culture. Besides the more than 200 people dedicated to looking for acquisitions, each GE Capital executive came to work every morning thinking about potential deals. It was part of the growth mind-set Gary brought to the business. The Harvard Business Review used GE Capital as a model for successfully integrating acquisitions, giving a blow-by-blow account of how Gary and his team did them—and there were a ton.

In the 1990s, Gary and Denis Nayden closed more than 400 deals involving over $200 billion in assets.

Gary lived for the deal, and everything with Gary was a negotiation. Denis Nayden remembers the time he and Gary were in Hong Kong and Gary went into a shop to buy a radio. He haggled with the salesperson for what seemed like an hour to get the price down and left happy with his bargain. Down the street, Gary nearly died when he spotted the same radio he had just bought in the window with a price tag lower than his highly negotiated purchase.

It drove him nuts over the weekend.

Gary also loved plotting strategies to sell deals. Mike Neal tells of the time he came in for his first preboard pitch to Gary in 1989. Mike wanted to buy Contel Credit, a telecom company leasing business. Throughout Mike’s entire presentation, Gary seemed bored and didn’t say a word—until Neal was completely finished.

“Mike,” he said, “this may be the worst acquisition we’ve ever had anyone pitch us, but we have another deal that’s big and sporty. It’s a commercial aircraft deal we really like. We’re going to let you take your deal up to the board meeting first and put you right in front of the deal we like. Jack seldom turns down two in a row. You’ll set us up to get the okay.”

Mike came in and pitched. We bought his deal. Gary’s preferred transaction got shot down.

We fought like hell over a lot of deals, but Gary had a very high batting average.

Years before Japan allowed foreign investment, Gary had sent a small business development team there to scout potential opportunities. When the Japanese economy began to sour in the mid-1990s, the country’s banking and insurance sectors were overleveraged and filled with bad investments. Nonperforming loans were out of sight. They needed new capital and new ownership.

When Japan began to open to foreign investment, Gary’s early groundwork gave GE Capital a head start.

The first deal in 1994 was to acquire Minebea, the $1 billion consumer finance company subsidiary of a ball-bearing company. Along with Jay Lapin, then the head of GE Japan, Gary put together several innovative deals in consumer finance, insurance, and equipment leasing. A former lawyer in our appliance business, Jay was the perfect area executive. He had worked hard to gain the trust of Japanese regulators and the business community. He loved Japan and its people. They knew it and responded. The parties he held at his home when I visited Japan brought me together with the CEOs of many of the country’s largest corporations and key opinion leaders.

By 1998, we really hit stride. The GE Capital team made two more deals that year in life insurance, consumer finance, and leasing that put us on the map as a big player in financial services in Japan.

The first one in February was a $575 million joint venture with Toho Mutual Life Insurance. Mike Frazier brought the deal to the board. Mike, too, had been a GE auditor. He had worked for me in Fairfield, searching the world for best practices and had been president of GE Japan in the early 1980s. Mike had built a strong U.S. insurance company, integrating 13 separate acquisitions into a highly successful whole. Now he was planting a flag for his business in Japan, with Gary’s strong support.

I was scared stiff over this one, and I gave it a lot of push-back. Toho was a bankrupt company, and the scale and scope of the acquisition overwhelmed me. This was unfamiliar territory. I didn’t know the laws, and I wanted to make sure Mike and his team had done the homework to assess all the risks. So we had a lot of back-and-forth. During December, he shuttled to Tokyo and back several times to satisfy both our and the seller’s concerns. The deal closed shortly before Christmas.

The second deal, announced in July 1998, was our $6 billion acquisition of the consumer loan business of Lake, Japan’s fifth largest consumer finance company. Lake was a provider of short-term consumer loans through automated teller machines. With 600 branches across Japan and nearly 1.5 million customers, it made us a big player in consumer finance in Japan. This was a highly complicated deal with a virtually bankrupt company that took nearly three years of work to complete.

The first overture in 1996 by Dave Nissen was rejected because we refused to take over the company’s liabilities. A second offer a year later didn’t go much further. Finally, in 1998, Nissen and his team came up with an unusual structure to pull it off. We’d buy Lake’s personal loan operations and help set up a separate company that would hold the rest of Lake’s assets, including some $400 million worth of art bought by the company’s owner. We agreed to put extra money on the table—an earn-out—that would give Lake’s shareholders some upside if we hit certain earnings targets.

To get the deal done, we had to convince 20 different banks in Japan to take a discount on the debt they had issued to Lake. Nissen’s team even hired Christie’s to assess the value of the Picassos and Renoirs that hung in Lake’s offices. Though we weren’t buying all this fancy artwork, if Lake could raise more cash from the sale of these and other assets, we’d have to pay less under the earn-out provision.

Before bringing Lake to the GE Capital board, Nissen and his team hammered out the deal in eight preboard sessions with Gary, Dennis Dammerman, and CFO Jim Parke.

I liked the concept. After we acquired Lake, I was playing golf with Warren Buffett at Seminole when he told me he really loved the transaction we’d just completed in Japan. I always pictured Warren sitting in Omaha, being cagey and smart. I didn’t think of him as being all that global, but he has more tentacles out than anyone.

“How do you know about Lake?” I asked.

“That’s one of the best deals I’ve seen,” he said. “If you weren’t there, I would have taken that one.”

Warren was a bit more aggressive when in 2001 GE Capital tried to participate in a restructuring of Finova, a finance company. As a major bondholder of Finova, Warren was trying to do a workout of the troubled concern. I would have liked to have worked with Warren, but he couldn’t go with us because he already had a partner in Leucadia. We bid for the company. Warren improved his offer and won Finova.

This time, we were on the outside, looking in.

Gary Wendt was quirky, to say the least. You never knew where he was coming from or what kind of mood he would be in. One thing he didn’t like was supervision. Whether it was Larry Bossidy, Bob Wright, or me, any boss drove Gary nuts. Having a boss who said no once in a while really sent him off the wall.

Parting ways with Gary in late 1998 was an inevitable consequence of the CEO succession process.

Denis Nayden, president, and Mike Neal, an executive VP, were ready. Denis, who has worked at GE for 21 years, is a remarkably driven person, a superb underwriter with the brainpower to structure big, complex deals. His best characteristic is his tenacity. He can work a deal until there’s no blood left in it. While Gary was the big idea guy, Denis was always the get-it-done guy.

I always thought of Mike Neal as the soul of GE Capital. Unlike most managers there, he didn’t come to business with a financial background. A former sales manager in GE Supply, he had to learn the business—and he has. Mike’s greatest strength is the way he connects with people. He’s well-liked and witty, always ready with a quip to defuse the tension in a room.

Jim Parke has been chief financial officer since 1989 and a key part of the growth story. He has great judgment and knows the business backward and forward.

Dennis Dammerman, who had been in or out of the business three times during his career, gave us all comfort that we had the bridge of expertise to the next generation of leadership at GE Capital.

With this succession team in place, Gary and I concluded that he didn’t want to work for the next CEO at GE. He had earned and deserved great treatment, and his severance package reflected that. We also got a noncompete.

In June 2000, Conseco, the insurance and financial services company, was in deep yogurt. Their stock had plunged 33 percent in 1998 and 41 percent in 1999, and they needed help fast. The principal Conseco shareholders, Irwin Jacobs and Thomas Lee & Associates, wanted Gary to bail them out. In fact, Gary was the perfect guy for this turnaround assignment.

He could finally be his own boss.

One of my more enjoyable negotiations was getting phone calls from Jacobs, telling me why I should release Gary from our noncompete contract. I got my first call from Jacobs to ask how much I would want to let Gary out.

“Irwin, you must think I have hay between my teeth. You want me to negotiate against myself?”

Irwin asked if $20 million would do it.

“Forget it. I’m not letting him out. He’s too smart and too valuable.”

Irwin called several times and suggested higher prices, but nothing close to what Gary was worth.

Not long afterward, I got another call from David Harkins, a Conseco board member and interim chairman and CEO. Like Irwin, David was very pleasant, trying to mollify me into a deal, each time modestly upping the ante. After several more phone calls over two days, we worked out an agreement. I agreed to cancel the noncompete in exchange for Conseco buying out all of GE’s obligations to Gary and issuing 10.5 million warrants for GE to buy Conseco stock at $5.75 a share—the market price at the time of the agreement.

The nice thing about this deal is that everybody won. Gary found his ideal spot, a place where he’s the boss and his brains will work wonders. Conseco got the turnaround in stock price that it wanted, and we got to sit on the sidelines and cheer for Gary again. We had skin in the game and could take the ride with him.

When Gary left, I named Dennis Dammerman the new chairman of GE Capital Services and he was elected a GE vice chairman. We promoted Denis Nayden from chief operating officer to president and CEO. I felt the two of them—both long involved in GE Capital’s success—would give us the leadership we needed to take the business into the next century. They kept the team intact, and GE Capital continued to build on its great strengths. In 1999 and 2000, the business acquired $47 billion in assets, including $33 billion outside the United States. GE Capital Services’s net income grew 17 percent in 2000 to $5.2 billion, another record year of double-digit earnings growth.

The numbers don’t tell the entire story.

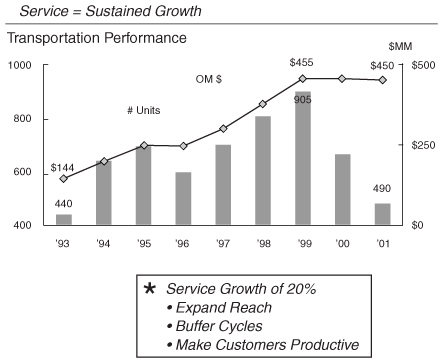

The chart I like best is one that was shown by Jim Colica, the longtime head of risk management, at a GE board meeting in June 2001 (below). It captures the growth and breadth and risk containment of GE Capital Services. While there were many blips in individual deals, the diversity of our business and our philosophy of controlled risk provided consistent growth. In 1980, GE Credit had 10 businesses and $11 billion in assets and was based only in North America. By 2001, GE Capital Services had 24 businesses and $370 billion in assets in 48 countries.

GE Capital Services is the story of melding finance and manufacturing. Combining creative people with the discipline of manufacturing and money really worked.

17

Mixing NBC with Light Bulbs

When we announced the acquisition of RCA in December 1985, NBC looked great. The network was a $3 billion business with 8,000 employees that had a lot of juice. It was on the verge of being first in prime-time ratings, first in late night programming, and first in Saturday morning children’s programs. Led by The Cosby Show, the highest-rated series on TV, we had nine of the 20 most-watched TV programs, including Family Ties, Cheers, and Night Court.

At the top of my mind was, How do we keep it going? I spent a lot of time getting a handle on the business during the integration meetings prior to completing the acquisition in June 1986.

It didn’t take a brain surgeon to realize that NBC president Grant Tinker and his entertainment division head, Brandon Tartikoff, were the two players who made NBC work. They had picked the shows that made NBC No. 1.

Grant was tired of commuting between New York and California and told me the day of the acquisition that he was not going to stay. Grant thought he had a leadership team in place that would keep NBC on top. He assured me everyone, including Brandon, was on board.

Fortunately, I had an old friend in Don Ohlmeyer, an independent TV producer, whom I had known from his association with Ross Johnson of Nabisco. We had played golf in the Nabisco/Dinah Shore Open. As a favor, Don called to tell me that Brandon was getting itchy.

At the age of 30, Brandon had been the youngest president of entertainment at a major network. He played a big role in NBC’s hits, including L.A. Law, Miami Vice, Cheers, The Cosby Show, Family Ties, and Seinfeld.

I didn’t want to lose him.

I called and asked Brandon to meet me for dinner at Primavera in New York on May 12. We really hit it off. He was a baseball nut like I am. I assured him things would be better than anything he had seen in the past. A month later, he signed a new four-year contract. Having Brandon heading up our entertainment team gave me confidence that GE could succeed in the network business.

During that summer, I interviewed the candidates on Grant Tinker’s staff to find a potential replacement for him as CEO of NBC. They were all good guys. Grant recommended I select Larry Grossman, then head of the news division. However, Larry didn’t have the business vision and edge I was looking for.

I told Grant I couldn’t go with any of his candidates. I asked him to meet with Bob Wright, who I felt from day one was the ideal person for the job. I arranged to have Grant fly up to Fairfield for dinner with Bob and his wife, Suzanne, who had been a key partner in Bob’s success. While Grant and Bob liked each other, nothing was going to dissuade Grant from wanting to promote one of his own guys.

Nevertheless, two months later, in August, I made Bob the CEO of NBC.

The reaction was predictable. People wondered how a “light bulb maker” could run a network. I was confident Bob was right for the job. He had been with me in Plastics, Housewares, and GE Capital, where he was CEO.

Bob had a lot going for him. His three-year stay with Cox Cable gave him the experience to help us expand beyond the traditional network business. His style radiated the management and creative skills to deal with talent. He was also a generous man, who took business friendships to deeper levels, always rushing to the side of someone with a personal crisis.

Bob and I were enjoying the success of NBC’s entertainment results, but there were clear signs of trouble ahead. NBC appeared stuck in the past. Entertainment was strong, but cable was steadily eroding its audience. News had been in the red for years and in 1985 was losing about $150 million a year. Typical of the entertainment business, spending seemed extravagant.

NBC wasn’t facing any of these realities.

We first tackled the losses in news. That brought us once again to NBC News president Larry Grossman. We were on different planets. He had been in advertising for NBC early in his career and later was president of PBS when Grant recruited him back in 1984.

Early in our relationship, Larry invited Bob and me along with our wives to his home with several of NBC’s stars and their spouses—Nightly News anchor Tom Brokaw, and Today show co-hosts Bryant Gumbel and Jane Pauley.

The Grossmans put on a nice evening.

There was only one problem: It was the night of the sixth game of the 1986 World Series, with my Red Sox playing the New York Mets. I had lived and died with the Sox since I was six years old.

This was the night they could finally win their first World Series in my lifetime. NBC was televising the game. I doubted Larry even knew it was World Series time. It turned out to be the saddest night in Red Sox history, when Bill Buckner let a ball dribble between his legs and the Red Sox eventually lost in the tenth inning.

I was shocked by Larry’s insensitivity to the game’s importance, but he might have felt equally upset that such a “trivial thing” could consume me. It was an odd night, but it wouldn’t be the last awkward experience between us.

Despite our demands on NBC News to cut losses, Larry stunned me in November when he showed up for the S-II budget review proposing an increase in spending.

Larry hated this kind of meeting. He thought it was demeaning to talk about costs with some business suits. He operated under the theory that networks should lose money while covering news in the name of journalistic integrity. His dismissive attitude only added to the friction. I was ripped after the meeting.

I stewed on it overnight. In the morning, I decided to confront the issue and asked Bob to helicopter with him up to a meeting in Fairfield.

‘ “Larry, I didn’t like the way the meeting went yesterday.”

“What didn’t you like?” he asked.

“I didn’t like your lack of responsiveness to our cost challenges.”

I never touched him. We were miles apart. After a couple of hours, Larry looked at his watch and said, “Jack, I’ve got to get this over with. I have to get back to New York because I have dinner with Chief Justice Burger.”

“Larry, if you like having dinners with the Justice Burgers of the world, you better get this thing in line fast. You work for Bob Wright. You work for GE. Get your costs in line or move on.”

We put up with Larry for 18 months until he left in July 1988.

During his transition out of the company, Larry, like so many people, ended up on the couch of Ed Scanlon. I met Ed during my RCA integration meetings. He was RCA’s head of human resources, a job that theoretically put him in charge of NBC’s human resources even though NBC thought of itself as pretty independent. I really liked him. Ed was straightforward and street smart. He was particularly helpful in melding the RCA and GE cultures.

I wanted to keep him but didn’t have a position equal to what he had at RCA. I thought he was the best HR person in RCA and felt he would help GE link with NBC. Ed lived in New Jersey, and all he had to do was move down about 40 floors at 30 Rock to take on the top HR job at NBC. The network had the visibility to make the job attractive to Ed.

He accepted.

What a lucky break for us. Ed related well with everyone, from union leaders to the on-air talent and their agents. He could bridge the gap between corporate and creative. Bob and I would work closely with him for the next 15 years.

NBC’s success was making it even more difficult for many of the top managers to face the new realities. Bob asked me to share my thoughts at his March 1987 management meeting at the Sheraton Bonaventure Hotel in Fort Lauderdale. It was a little bit like the first Elfun meeting in Westport six years earlier.

Not everyone was pleased.

I spoke before dinner to Bob’s top 100 executives and told them NBC had to change and adapt to a new world. “Cable is coming, and it’s going to change your life. Too many people in this room are living in the past. There are too many staff people living off the entertainment gravy train, and that train is not going to run forever. You must take charge of your destiny. If you don’t, Bob will.”

For the A players, this could be a real opportunity.

“For the turkeys,” I said, “it will be marginal at best.”

Less than 20 percent liked what I had to say. The rest thought I ought to be arrested or committed.

We looked long and hard for Larry Grossman’s replacement. Michael Gartner came highly recommended by Tom Brokaw, the anchor of Nightly News and the dean of NBC. Michael had great news credentials. He had been the front-page editor of The Wall Street Journal and editor of the Des Moines Register and the Louisville Courier-Journal. Despite a somewhat quirky personality, he had a reputation for doing a top-notch job editorially and financially. He seemed the perfect fit, and in many ways he was.

Gartner joined in July 1988. His first management change would end up leading to a great NBC success story.

Tim Russert had been serving as Larry Grossman’s deputy. Gartner wanted his own guy, so Bob Wright suggested that Russert get an operating job. Tim had been a staff assistant to Governor Mario Cuomo and Senator Pat Moynihan, so he’d never run anything.

Michael offered him the job of bureau chief for NBC’s Washington bureau. Tim resisted, worried about leaving the center of power in New York for an outpost. I spent an hour with him, describing why he should jump at the job to manage NBC News’s biggest field operation. Here was the chance to show us what he could do as a manager.

Tim’s move to Washington was a win for everyone. He hired Katie Couric as a Washington correspondent in 1989. That was the start of what would be an incredible career.

Katie became co-host of the Today show in April 1991 and immediately caught on, establishing an easy rapport with the morning audience. The ratings began to climb. Katie has been the show’s longest recognizable star. Sadly, Katie had a personal tragedy when her husband, Jay Monahan, died of colon cancer in 1998.

All of America grieved with her. To increase awareness of colon cancer, she even went on national TV to have a colonoscopy, bringing attention to the procedure. During a recent physical, my doctor told me that as a result of Katie’s efforts he was booked for the next year.

Meanwhile, Tim Russert’s insights from Washington impressed Michael during the daily teleconferences with bureau chiefs for the Nightly News. In 1990, Michael put him on Meet the Press as a panelist. A year later, Tim replaced Garrick Utley as host of this show when Garrick moved to New York with the weekend Today show.

Tim has been special in so many ways. He’s taken Meet the Press to first in the ratings, becoming arguably the leading political commentator on TV. His fame has not gone to his head. He’s a straight shooter and extremely popular everywhere, particularly in GE. He’ll go to any of our plants to give a talk and meet with employees.

I wasn’t sure Tim understood our stock option program when I got a notice that his ten-year-old grant was about to expire in three months. I called him and said, “You know, this piece of paper you have in your drawer is worth a lot of money, and it runs out in 90 days.”

“Jack, I’ve got faith,” he said. Turned out he had more faith and more smarts than most of us and did very well by holding his options to the last days.

Gartner didn’t put just Tim into a position to succeed. He also was responsible for making Jeff Zucker the executive producer of the Today show. Jeff had joined Dick Ebersol, the head of NBC Sports, straight out of Harvard as an assistant at the Seoul Olympics. Dick liked him, took him under his wing, and got him involved in the Today show. With Ebersol’s encouragement, Gartner and Bob decided to make Jeff, at age 26, executive producer of the Today show. Their confidence was rewarded a thousand times over with the tremendous success of the Today show under Jeff’s leadership. Jeff was named president of NBC’s entertainment division in 2001. Now we need him to work his magic there.

Everything wasn’t perfect under Michael. His unfamiliarity with TV and his management style caused some issues. His courage to attack the NBC News cost structure, while popular with us, didn’t win him support there. But Michael suffered his biggest blow when a major controversy broke out over a Dateline news feature. On November 17, 1992, Dateline ran a segment on allegations about the safety of General Motors pickup trucks. “Waiting to Explode?” depicted GM trucks exploding on impact. On February 8, 1993, GM sued NBC, accusing the network of rigging the crash tests.

An internal investigation found that some of the reported facts were suspect. Although Jane Pauley wasn’t involved in the GM story, she agreed to go on Dateline and read an on-air apology that brought the issue to closure. That was the ultimate in being a team player. Jane was great to do that, and her well-earned credibility with the audience made a huge difference.

Although Michael Gartner was not directly responsible, he never recovered from the Dateline incident. Before resigning on March 2, Michael was in the process of enticing Neal Shapiro from ABC to become executive producer of Dateline. Neal is creative, genuine in every way, and deservedly one of the most popular figures at NBC. He not only restored the show’s credibility, he expanded Dateline into three to four prime-time hours every week. The show became a huge success for NBC, and so did Neal. In 2001 he became president of NBC News.

After the Dateline incident, Bob interviewed just about everybody in the news business to replace Gartner. Again, Tom Brokaw played a big role. Tom’s reputation made him the public face of NBC News. He’s been a mentor to many young newspeople over a 30-year career.

Tireless and very demanding of himself, Tom has been a great help to Bob, who has used his counsel on almost every major decision at NBC News. After Bob interviewed all the obvious candidates, it was Tom who suggested that Bob talk to Andy Lack, then an executive producer at CBS.

Andy and Bob had a long dinner at the Dorset Hotel, where Andy made a big impression. After this dinner, Bob wanted me to meet him, and I did a couple of days later.

I think I’ve told everyone that Andy was the most exciting person I ever interviewed for a job. He was totally different from any of the news leaders I had met. He was humorous, spontaneous, filled with energy, and totally comfortable with himself—traits by now you know I find appealing.

He charmed the hell out of me.

Twenty minutes into the conversation, I turned to Bob and said, “What are we waiting for?”

“Let’s do it,” Bob said.

I looked at Andy and asked, “Why aren’t you jumping up and down? This is a huge job we’re offering you.”

He responded, “After all the stuff I heard about you guys, I’m wondering whether I’d get the resources to get news back on its feet.”

We both assured him he’d get what he needed to turn around the news operation.

Andy called Bob on Sunday and took the job. He quit CBS on Monday morning and joined us in early April 1993.

Meanwhile, Bob was moving ahead on cable.

When we bought NBC, the network’s only cable asset was a one-third financial interest in the Arts & Entertainment channel. Bob was desperate to enter the cable business in a big way. The window was closing. In early 1987, he hired Tom Rogers, who had spent several years on the Hill working on telecommunications policy as a congressional aide to Representative Tim Wirth. Bob put Tom in charge of expanding NBC’s cable efforts. He had great contacts in the industry and was a terrific negotiator and a brilliant strategist.

Tom and Bob went first to Chuck Dolan, a pioneer of the cable TV business. Chuck had founded Cablevision Systems in Long Island, a company that became one of the largest U.S. cable operators. Chuck launched Bravo, was co-founder of HBO, and had developed a group of other cable properties. Bob knew Chuck and his family and had almost left Cox in the early 1980s to become president of Cablevision.

They struck a partnership in January 1989, with NBC buying half of Chuck’s Rainbow Properties for $140 million. The deal gave us interests in Bravo, American Movie Classics, Sports Channel USA, and regional sports services across the United States. NBC also would buy stakes in Court TV, the Independent Film Channel, the History Channel, and Romance Classics.

Bob’s deal with Chuck let either side bring to the partnership any new ideas we wanted to develop from scratch. The first big one was CNBC, the business news network. I loved the idea from the start. I thought there was an opportunity for a business channel, and unlike entertainment and sports, business programming wouldn’t involve any rights fees.

The only other competitor at the time was Financial News Network (FNN), and it was losing money. Chuck agreed to go into CNBC with us on a 50/50 basis, and CNBC went on the air in April 1989.

By 1991, our cumulative losses were nearly $60 million. Business news was not taking off. FNN went into bankruptcy in January. At that time, FNN had access to 32 million homes. CNBC had 20 million subscribers. Chuck had no interest in going after FNN in bankruptcy.

He’d had enough. Chuck withdrew his 50 percent ownership of CNBC, and we went after FNN alone.

We thought we could get it for $50 million. We were all surprised when the opening bid from Westinghouse and Dow Jones was $60 million. The bidding reached $150 million when Bob and Tom Rogers came back and said they needed another $5 million. Silly as it now seems, the GE guys, including myself, agonized over our bid because it was three times our preliminary evaluation of the deal. Fortunately, we badly wanted a financial news network, and the extra $5 million closed the deal.

The deal more than doubled our distribution. We retained the best FNN talent, including Ron Insana and Sue Herera, who today co-anchor our top-rated Business Center news program, and Bill Griffeth, who hosts Power Lunch.

On the entertainment side, things weren’t going as well.

From 1988 to 1992, we introduced dozens of shows that didn’t click. I wasn’t worth a nickel here. After acquiring NBC, I went to Hollywood once to look at the pilots for the new prime-time schedule.

You ought to hear the presentations and the wild predictions of success for each pilot. Every show has a shot: a great producer, sensational stars, an Emmy-winning this or that. Every comedy is Seinfeld reincarnated and every drama is ER.

Thank God there are so many optimists in the business.