SECTION II

BUILDING A PHILOSOPHY

7

Dealing with Reality and “Superficial Congeniality”

On April 1, 1981, I was like the dog who caught the bus. I finally had the job.

Despite all the experiences that had gotten me this far, I wasn’t nearly as sure of myself as I pretended to be. Outwardly, I had a pretty good dose of self-confidence, and those who knew me would have described me as self-assured, cocky, decisive, quick, and tough. Inwardly, I still had plenty of insecurities. Whenever I had to get up in front of people, I struggled with my speech impediment. I fussed with a comb-over to disguise my receding hairline. And when someone asked me how tall I was, I had myself believing I was at least an inch and a half taller than the five feet eight I really was.

I came to the job without many of the external CEO skills. I had rarely dealt with anyone in Washington, even though the government was more into business than ever. I had little experience dealing with the media. My only press conference was the scripted session with Reg on the day GE announced I would be the next chairman. I had only one or two brief outings before the Wall Street analysts who followed GE. And our 500,000-plus shareholders had no idea who Jack Welch was and whether he would be able to fill the shoes of the most admired businessman in America.

But I did know what I wanted the company to “feel” like. I wasn’t calling it “culture” in those days, but that’s what it was.

I knew it had to change.

The company had many strengths. It was a $25 billion corporation, earning $1.5 billion a year, with 404,000 employees. It had a triple-A balance sheet, and its products and services permeated almost every part of the GNP, from toasters to power plants. Some employees proudly described the company as a “supertanker”—strong and steady in the water. I respected that but wanted the company to be more like a speedboat, fast and agile, able to turn on a dime.

I wanted GE to run more like the informal plastics business I came from—a company filled with self-confident entrepreneurs who would face reality every day. Every milestone could trigger a celebration that would make business fun. With a few notable exceptions, fun was not the norm at the time.

I knew the benefits of staying small even as GE was getting bigger. The good businesses had to be sorted out from the bad ones. I wanted GE to stay only in businesses that were No. 1 or No. 2 in their markets. We had to act faster and get the damn bureaucracy out of the way.

The reality was that at the end of 1980, GE was, like much of American industry, a formal and massive bureaucracy, with too many layers of management. It was ruled by more than 25,000 managers who each averaged seven direct reports in a hierarchy with as many as a dozen levels between the factory floor and my office. More than 130 executives held the rank of vice president or above, with all kinds of titles and support staffs behind each one: “vice president of corporate financial administration,” “vice president of corporate consulting,” and “vice president of corporate operating services.”

There were eight regional or “consumer relations” vice presidents located around the country without direct sales responsibility. The bureaucracy this structure created was huge. (Today, in a company six times as large, we have roughly 25 percent more vice presidents. We have fewer managers, and most now average over 15 direct reports, not seven, with in most cases fewer than six layers between the shop floor and the CEO.)

It didn’t take very long to bump up against some of the worst practices.

A couple of months into the job, Art Bueche, the head of our R&D operations, stopped by my office. He wanted to give me a series of cards with written questions for our upcoming planning sessions with GE business leaders. The centerpiece of these meetings, held every July, were thick planning books that contained detailed forecasts of sales, profits, capital expenditures, and myriad other numbers for the next five years. These books were the lifeblood of the bureaucracy. Some GE staffers in Fairfield actually graded them, even assigning points to the pizzazz of each cover. It was nuts.

I looked through the cards Art handed me, surprised to see corporate crib sheets filled with “I gotcha” questions.

“What the hell am I supposed to do with these?”

“I always give the corporate executive office these questions. That lets them show the operating people that they studied the planning books,” he replied.

“Art, this is crazy,” I said. “These meetings have got to be spontaneous. I want to see their stuff for the first time and react to it. The planning books get the conversation going.”

The last thing I wanted was a series of tough technical questions to score a few points. What was the purpose of being CEO if I couldn’t ask my own questions? The corporate staff had its rear end to the field—and it was too busy “kissing up” to the bosses.

The corporate executive office, including my vice chairmen, wasn’t the only group at headquarters getting crib sheets. For every business review, headquarters people loaded up their own staff heads with questions.

We had dozens of people routinely going through what I considered “dead books.” All my career, I never wanted to see a planning book before the person presented it. To me, the value of these sessions wasn’t in the books. It was in the heads and hearts of the people who were coming into Fairfield. I wanted to drill down, to get beyond the binders and into the thinking that went into them. I needed to see the business leaders’ body language and the passion they poured into their arguments.

There were too many passive reviews. One annual ritual was the spring trip to the appliance product review in Louisville. A team of designers and engineers hauled out cardboard and plastic mock-ups. Here we were from Fairfield, being asked for our opinions on futuristic refrigerators, stoves, and dishwasher models.

I’ll never know how many of these models ever made it to the dealer’s selling floor. I did know that some of the mock-ups had to have the dust brushed off them because they had been paraded out in prior reviews for years. I also knew that the comments from the Fairfield contingent, including myself, were of little value. This ritual was a waste of everyone’s time.

I wanted to break the cycle of these dog-and-pony shows. Hierarchy’s role to passively “review and approve” had to go.

After the planning sessions my first summer, I tried to create the environment I was looking for with my own staff. I thought a good way to break the ice was to take everyone off site for a couple of days. In my earlier jobs, we always found a way to make sure we got a dose of golf mixed with the business at first-class golf courses (places like Harbor Town at Hilton Head and the Cascades at the Homestead).

I had just become a member of Laurel Valley, a wonderful golf club just outside Pittsburgh. So in the fall of 1981, I invited about 14 executives to Laurel for the two-day retreat. The group included all the functional staff heads and our seven sector executives. It was my first real attempt at creating a collegial group at the top, what we would later call the CEC, or Corporate Executive Council.

Among the 14 executives, a core group of at least seven or eight advocates signed up for the new agenda. Reg was right when he picked John Burlingame and Ed Hood as vice chairs. They were supportive and never undermined my efforts, despite the fact that they may have had some reservations about the pace of change.

Together, in fact, they served as a moderating force. Larry Bossidy, the guy I had discovered over a Ping-Pong table, had come to Fairfield as a sector executive in 1981 and had become a business soul mate. We both shared a hatred of bureaucracy. I had strong support from two of my most senior staff guys, chief financial officer Tom Thorsen and human resources chief Ted LeVino.

Tom was an old associate from Pittsfield. He had been tapped a few years earlier by Reg to come to Fairfield as CFO. He understood what we wanted to do. While he thought it was a sport to take shots at me, I still loved him for his candor and his smarts. LeVino represented the bridge between the old and the new GE. His support for many of the early initiatives was vital.

If I didn’t have all 14 of our top executives completely behind me at this moment, I knew I had enough to start the process. The first morning at Laurel Valley, I filled a conference room with blank easels, anxious to capture everyone’s thoughts. I got up in front of the crowd and started asking what they thought about our No. 1 or No. 2 strategy, what they liked and disliked about GE, and what things we ought to change quickly. We spent time discussing the just-concluded planning sessions and how they could be improved. Creating an open dialogue was difficult. Only those I worked closely with were willing to let it rip. Most of the guys didn’t want to stick their necks out.

We got through the morning with only half the group engaged.

After a fun afternoon of golf and a few drinks over dinner, things loosened up a little bit and a few more got involved. The second day was more of the same. Perhaps it was too early. Many of them weren’t sure where they stood or what they were dealing with. The two-day outing failed to build any kind of consensus for change.

I thought we needed a revolution. It was obvious we weren’t going to get one with this team.

GE’s culture had been built for a different time, when a command-and-control structure made sense. Having been in the field, I had a strong prejudice against most of the headquarters staff. I felt they practiced what could be called “superficial congeniality”—pleasant on the surface, with distrust and savagery roiling beneath it. The phrase seems to sum up how bureaucrats typically behave, smiling in front of you but always looking for a “gotcha” behind your back.

Organizational layers were another residue of size. I used the analogy of putting on too many sweaters. Sweaters are like layers. They are insulators. When you go outside and you wear four sweaters, it’s difficult to know how cold it is.

On one early plant tour in a Lynn, Massachusetts, jet engine factory, I ended up in the boiler room with a group of employees who knew many of the guys I grew up with in Salem. During a casual conversation about old times, I happened to learn that they had four layers of management supervising the boiler operation. I couldn’t believe it. It was a funny way to find out about layers. I used that story at every opportunity.

Another effective analogy was comparing an organization to a house. Floors represent layers and the walls functional barriers. To get the best out of an organization, these floors and walls must be blown away, creating an open space where ideas flow freely, independent of rank or function.

In the 1970s and 1980s, big business had too many layers—too many sweaters, too many floors and walls. The impact of these layers was seen most easily in the capital appropriations request process. When I first became CEO, almost every request for a significant capital expenditure would come to me for approval. A package of paper would arrive on my desk for a signature to buy something like a $50 million mainframe computer. In some cases, 16 other people had already signed it, and my signature was the last one required. What value was I adding?

I did away with that process and haven’t signed an appropriations approval in at least 18 years. Each business leader has the same delegation of authority that the board gave me. At the beginning of every year, the business made the case for the capital it needed. We allocated the dollars, ranging from $50 million to several hundred million. They own it and decide how far to delegate the spending authority. The people closest to the work know the work best. They become more accountable. They take their recommendations more seriously if they know a bunch of signatures aren’t piled on top of them.

In those days, I was throwing hand grenades, trying to blow up traditions and rituals that I felt held us back. In the fall of 1981, I tossed one in the middle of the Elfun Society, an internal management club at GE. (Elfun was short for Electrical Funds, a mutual fund that its members could invest in.) It was a networking group for white-collar types. Being an Elfun was considered a “rite of passage” into management.

I didn’t have a lot of respect for what Elfun was doing—I thought it represented the height of “superficial congeniality.”

It evolved into an elitist group for those who wanted to be seen by their bosses or their bosses’ bosses at dinner meetings. I remember paying dues and going to a few of these dinners early in my career. If a corporate vice president who oversaw a business in the town showed up, he’d get a packed house. Everyone would go to win points and get face time. If the speaker had no real impact on their careers, Elfun would have trouble filling a small conference room.

As the new CEO, I was invited to speak before the group’s annual leadership conference in the fall of 1981. It was supposed to be a nice meeting, one of those pat-on-the-back speeches from the new guy. I showed up at the Longshore Country Club in Westport, Connecticut, where some 100 Elfun leaders from all the local chapters in the United States gathered. After dinner, I got up and delivered what one member still remembers as a classic “stick-in-the-eye” speech.

“Thank you for asking me to speak. Tonight I’d like to be candid, and I’ll start by letting you reflect on the fact that I have serious reservations about your organization.”

I described Elfun as an institution pursuing yesterday’s agenda. I told them I never could identify with their recent activities.

“I can’t find any value to what you’re doing,” I said. “You’re a hierarchical social and political club. I’m not going to tell you what you should do or be. It’s your job to figure out a role that makes sense for you and GE.”

There was stunned silence when I ended the speech. I tried to soften the blow by milling around the bar for an hour. However, no one was in the mood for cheering up.

The next morning, one of our senior officers, Frank Doyle, went as he always did to meet with the group at its opening business session. This time he had a real job. He had to pick up the pieces from my speech the evening before. Frank just about walked into a wake. They felt as if they had been run over by a train. Like me the night before, he challenged them to change.

A month later, Elfun president Cal Neithamer called me and asked for a meeting. I invited Cal, an engineer in our transportation business in Erie, Pennsylvania, to Fairfield for lunch. He came armed with charts, but more important, he was excited about a new idea for Elfun. His dream was to turn the organization into an army of GE community volunteers. The idea came at a time when President Reagan was urging people to volunteer their time—to step in where government was reducing its role.

God, was I excited by Cal’s vision! I’ve never forgotten that lunch. Although Cal retired a few years ago, I still hear from him more or less once a year. What a job he and his successors did. Today, Elfun has more than 42,000 members, including retirees. They volunteer their time and energy in communities where GE has plants or offices. They have mentoring programs for high school students that have achieved remarkable results.

At Aiken High School, an inner-city school in Cincinnati, coaching by GE volunteers raised the percentage of graduating students going on to college to more than 50 percent from less than 10 percent in the past ten years. Similar programs are going on in schools in every significant GE community, including Albuquerque, Cleveland, Durham, Erie, Houston, Richmond, Schenectady, Jakarta, Bangalore, and Budapest.

They’ve also done everything from building parks, playgrounds, and libraries to repairing tape players for the blind. Today, no one is excluded from the organization, whether the person is a factory worker or a senior executive. Membership is determined solely by the desire to give back. Some 20 years later, the organization I almost turned my back on has become one of the best things about GE. I love the organization, the people in it, what it stands for, and what it has done.

Elfun’s self-engineered turnaround became a very important symbol. It was just what I was looking for.

Not everything I wanted to change was at headquarters. Some of the real eye-openers were far from my office. I spent most of 1981 with a team in the field reviewing businesses—just as I had done for ten years. I had a good feel for about a third of the company and wanted to dig into the rest.

I quickly found that the bureaucracy I saw when managing appliances and lighting was nothing compared to what I would see in some of GE’s other operations. The bigger the business, the less engaged people seemed to be. From the forklift drivers in a factory to the engineers packed in cubicles, too many people were just going through the motions.

Passion was hard to find. Schenectady, the home of our power turbine business, was particularly frustrating. It had been our flagship business for GE for a long time, replacing lighting, our first business, as the core of the company. It had great technology, and its gas turbines were the envy of the world. With $2 billion in sales and 26,000 employees, more than 20,000 in Schenectady, it was important—and it “acted” important, despite only making $61 million of net income.

Power represented much of what had to change, not the technology and products, but the attitudes. Too many managers considered their positions as rewards for service to the company, a career capstone rather than a fresh opportunity. There was an attitude that customers were “fortunate” to place orders for their “wonderful” machines. The long-cycle nature of the business, with product life cycles and order backlogs measured in years, only compounded the lack of pace, excitement, and energy.

Little did I know that out of all of these field visits, I’d stumble upon a relatively small and troubled business that would prove to be a big help. It was our nuclear reactor business in San Jose, California. Nuclear power was one of GE’s three big 1960s ventures, along with computers and aircraft engines. Our engine business was going strong, but computers had already been sold, and our nuclear business was filled primarily with “hope.”

No business was undergoing more change than the nuclear power industry at that moment. Only two years earlier, in 1979, the Three Mile Island reactor accident in Pennsylvania put an end to what little public support remained for nuclear energy. Utilities and governments were reevaluating their investment plans for a nuclear future. Ironically, this once promising GE business would become the perfect role model for my “reality” theme.

The people who worked in San Jose were among the best and brightest of their time. Coming out of graduate school in the 1950s and 1960s, they had invested their lives in the promise of nuclear energy. They were the Bill Gateses of their generation, expecting to change the way we live and work.

In the spring of 1981, I visited this billion-dollar business. During my two-day review, the leadership team presented a rosy plan, assuming three new orders for nuclear reactors a year. They had a terrific track record in the early 1970s, selling three to four reactors each year. The business saw the Three Mile Island disaster as little more than a blip.

Their view was completely at odds with reality. They had received no new orders in the last two years and had suffered a $13 million loss in 1980. Though they would turn a small profit in 1981, the reactor side of the business by itself was on its way to a $27 million loss.

I listened for a while before interrupting with what they saw as a bombshell.

“Guys, you’re not going to get three orders a year,” I said. “In my opinion, you’ll never get another order for a nuclear reactor in the U.S.”

They were shocked. They argued, with the not-so-subtle implication being, “Jack, you really don’t understand this business.”

That was probably true, but I had the benefit of a pair of fresh eyes. I hadn’t invested my life in this business. I loved their passion, even though I felt it was misdirected.

Their arguments contained a lot of emotion but few facts. I asked them to redo the plan on the assumption they’d never get another U.S. order for a reactor.

“You figure out how to make a business out of selling just fuel and nuclear services to the installed base,” I said.

At the time, GE had 72 active reactors in service. Safety was the principal preoccupation of both utility managers and government regulators. We had an obligation and an opportunity to keep those reactors up and running safely.

Obviously, our review didn’t go well. I had thrown a bucket of cold water on their dreams. Toward the end of our meeting, they resorted in frustration to one of the favorite “when all else fails” arguments heard in business.

“If we take the orders out of the plan, you’ll kill morale and you’ll never be able to mobilize the business when the orders come back.”

That wasn’t the first or the last time I heard desperate business teams use the argument. That reasoning falls into the same category as the other plea I often heard during tough times: “You’ve cut all the fat out. Now you’re into bone and you’ll ruin the business if we cut more.”

Both arguments don’t make it. They’re both weak. Management always has a tendency to take the smallest bite of the cost apple. Inevitably, managers have to keep going back, again and again, to cut more as markets deteriorate. All this does is create more uncertainty for employees. I’ve never seen a business ruined because it reduced its costs too much, too fast.

When good times come again, I’ve always seen business teams mobilize quickly and take advantage of the situation.

Fortunately, the leader of this business, Dr. Roy Beaton, was the most realistic GE trooper in the room. He reluctantly accepted the challenge. I left not knowing what I’d get. During the summer, we had a few more heated exchanges when the team pleaded its case to put one or two reactors in the plan instead of three. I remained stubbornly committed to zero and the full development of a fuel and services business.

To their credit, by the fall of 1981, the team—now headed by Warren Bruggeman, who succeeded the retiring Beaton—had a plan and was prepared to implement it. They reduced the size of the salaried employees in the reactor business from 2,410 in 1980 to 160 by 1985. They eliminated most of the reactor infrastructure and focused only on research for advanced reactors in the event the day would come when the world’s view of nuclear changed. The service business became very successful and was an early indicator that service could play a huge role in GE’s future. With its success, nuclear’s overall net earnings grew from $14 million in 1981 to $78 million in 1982, and to $116 million in 1983.

Some 20 years after that first meeting, the business has gotten orders for only four of their technologically advanced reactors. Not one of them has come from the United States. The team built a profitable fuel and services business that has made money every year. The nuclear business kept GE’s obligations to the utilities’ installed base and invested consistently to support advanced reactor research.

Their story of success was one of the thrills of my early days as CEO. It had little to do with economics but a lot to do with the company “feel” I was looking for. The people who engineered the transformation at our nuclear business were not “typical Jack Welch types.” They weren’t young, loud, or confrontational. They didn’t see the bureaucracy as the enemy. They were GE careerists and mainstreamers.

The opportunity to make heroes out of people who were not obvious Welch disciples was a breakthrough. It sent a clear message: You didn’t have to fit a certain stereotype to be successful in the new GE. You could be a hero no matter what you looked like or how you acted. All you had to do was face reality and perform. That message was a big deal at a time when some GE people were unsure where they stood or whether or not they had some kind of “nut” running the company.

I used this nuclear story over and over again in the first few years as CEO to pound home the need for a reality check. I shouted it out from every rooftop. Facing reality sounds simple—but it isn’t. I found it hard to get people to see a situation for what it is and not for what it was, or what they hoped it would be.

“Don’t kid yourself. It is the way it is.” My mother’s admonition to me many years ago was just as important for GE.

In a business plan, there’s little percentage in betting on hope. Self-delusion can grip an entire organization and lead the people in it to ridiculous conclusions. Whether it was appliances in the late 1970s, nuclear in the early 1980s, or dot-coms at the turn of the century, getting people to face reality was the first step toward an eventual solution.

When I became CEO, I inherited a lot of great things, but facing reality was not one of the company’s strong points. Its “superficial congeniality” made candor extremely difficult to come by. I got lucky. The changes at our nuclear reactor business and at Elfun gave me important weapons to demonstrate what I wanted GE to “feel” like.

I told their stories again and again to every GE audience at every opportunity. For the next 20 years, I used that same storytelling technique to get ideas transferred across the company.

Slowly, people started listening.

8

The Vision Thing

My first time in front of Wall Street’s analysts as chairman was a bomb.

I had been in the job for eight months when I went to New York City on December 8, 1981, to deliver my big message on the “New GE.” I had worked on the speech, rewriting it, rehearsing it, and desperately wanting it to be a smash hit.

It was, after all, my first public statement on where I wanted to take GE. You know, the vision thing.

However, the analysts arrived that day expecting to hear the financial results and the successes achieved by the company during the year. They expected a detailed breakdown of the financial numbers. They could then plug those numbers into their models and crank out estimates of our earnings by business segment. They loved this exercise. Over a 20-minute speech, I gave them little of what they wanted and quickly launched into a qualitative discussion around my vision for the company.

The setting for this event was the ornate ballroom of the Pierre Hotel on Fifth Avenue. The GE stagehands had been there for a full day of advance work. I rehearsed my remarks behind a podium hours before the analysts arrived. Today it’s hard to imagine the formality of it all.

My “big” message (see appendix) that day was intended to describe the winners of the future. They would be companies that “search out and participate in the real growth industries and insist upon being number one or number two in every business they are in—the number one or number two leanest, lowest-cost, worldwide producers of quality goods and services. . . . The managements and companies in the eighties that don’t do this, that hang on to losers for whatever reason—tradition, sentiment, their own management weaknesses—won’t be around in 1990.”

Being No. 1 or No. 2 wasn’t merely an objective. It was a requirement. If we met it, we were certain that by the end of the decade, this central idea would give us a set of businesses unique in the world. That was the “hard” message of the day.

As I moved into “soft” issues like reality, quality, excellence, and (would you believe?) the “human element,” I could tell I was losing them. To be a winner, we had to couple the “hard” central idea of being No. 1 or No. 2 in growth markets with intangible “soft” values to get the “feel” that would define our new culture. About halfway through, I had the impression I would have gotten as much interest if I’d talked about my Ph.D. thesis on drop-wise condensation.

I pressed on, not letting their blank stares discourage me. Today, some of this might sound like corporate cliché. In fact, looking back on that speech years later, I can’t believe how formal it was.

“We have to permeate every mind in this company with an attitude, with an atmosphere that allows people—in fact, encourages people—to see things as they are, to deal with the way it is, not the way they wished it would be,” I said. “Establishing throughout the organization this concept of reality is a prerequisite to executing the central idea—the necessity of being number one or number two in everything we do—or do something about it.”

I went on to say that quality and excellence would create an atmosphere where all our employees would feel comfortable stretching beyond their limits, to be better than we ever thought we could be. This “human element” would foster an environment where people would dare to try new things, where they would feel assured in knowing that “only the limits of their creativity and drive would be the ceiling on how far and how fast they would move.”

By doing all that, melding these hard and soft messages, GE would become a place that was “more high-spirited, more adaptable, and more agile” than other companies a fraction of our size. We wouldn’t merely grow with the GNP (gross national product), an objective of many big companies at that time. Instead, GE would be “the locomotive pulling the GNP, not the caboose following it.”

At the end, the reaction in the room made it clear that this crowd thought they were getting more hot air than substance. One of our staffers overheard one analyst moan, “We don’t know what the hell he’s talking about.” I left the hotel ballroom knowing there had to be a better way to tell our story. Wall Street had listened, and Wall Street yawned. The stock went up all of 12 cents. I was probably lucky it didn’t drop.

I was sure the ideas were right. I just hadn’t brought them to life. They were just words read on stage by a new face.

The highly structured formality of GE’s analyst meetings didn’t help my cause. Every detail was planned, even the seating arrangements. The analysts sat politely in their seats. GE staffers strolled up and down the aisles, collecting cards that the analysts had scribbled questions on. The cards were brought to three other GE people, including the chief financial officer, who sat behind a long table at the side of the room. Their job was to weed out the potentially embarrassing, controversial, or tough questions they felt the chairman wouldn’t or couldn’t answer.

The “lay-ups” were delivered to me.

What a difference between that day and GE analyst meetings now. Today there are no scripts. Charts are used, and you can’t get through two of them without a question or a challenge. We have intellectual food fights now, just like the reviews inside GE. We come away a lot smarter about what’s on the minds of investors—and the analysts are better informed about GE’s outlook and strategic direction.

My first meeting was a flop, but everything we did over the next 20 years, stumbling two steps forward, one back, was toward the vision that I laid out that day. We lived that hard reality of No. 1 or No. 2 and fought like mad to get that soft “feel” into the company.

The central idea came from my earlier experiences with good and bad businesses and was supported by the thinking of Peter Drucker. I began reading Peter’s work in the late 1970s, and Reg introduced us during my transition to CEO. If there was ever a genuine management sage, it is Peter. He always dropped a few unique pearls into his many management books.

The clarity of No. 1 or No. 2 came from a pair of very tough questions Drucker posed: “If you weren’t already in the business, would you enter it today?” And if the answer is no, “What are you going to do about it?”

Simple questions—but like much that is simple, they were also profound. Those were especially good questions to ask at GE. We were in so many different businesses. In those days, if you were in a business that was profitable, that was enough reason to stay in it. Changing the game, getting out of low-margin, low-growth businesses and moving into high-margin, high-growth global businesses, was not a priority.

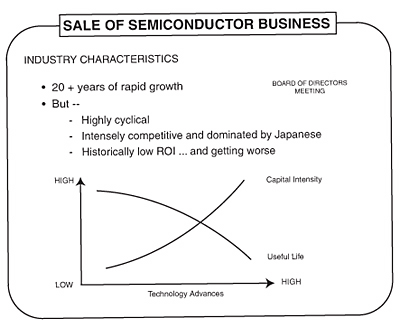

At that time, no one in or outside the company perceived a crisis. GE was an American icon, the tenth largest corporation by size and market capitalization. The Asian assault had been coming for many years, swamping one industry after another; radios, cameras, televisions, steel, ships, and finally autos. We saw it in our television manufacturing business as global competition—particularly from the Japanese—began eating up profits. We had several vulnerable businesses, including housewares and consumer electronics.

Yet if you were in our housewares business back then, plugging along making toasters and irons, and if that’s all you knew and it was profitable, that was enough. Even today, we’ll have these crazy conversations where people will say, “Well, you’re making a profit. What’s wrong?”

Well, in some cases, there’s a lot wrong. If it’s a business without a long-range competitive solution, it’s just a matter of time before it’s over.

The No. 1 or No. 2, “fix, sell, or close” strategy passed the simplicity test. People discussed it and understood it, and most agreed to it intellectually. When it came time to implement it, the emotional connection was more difficult for people to make. Those working in a clear No. 1 business had no trouble. In businesses that weren’t leaders, people felt tremendous pressure. They had to face the reality that their business had to do something fast—or that new guy in Fairfield might sell it on them.

Like every goal and initiative we’ve ever launched, I repeated the No. 1 or No. 2 message over and over again until I nearly gagged on the words. I tried to sell both the intellectual and emotional cases for doing it. The organization had to see every management action aligned with the vision.

Like most visions, the No. 1 and No. 2 strategy had limits.

Obviously, some businesses have become so commoditized that leadership positions give you little or no competitive advantage. It made little difference if we were No. 1 in electric toasters or irons, for instance, where we had no pricing power and were facing low-cost imports.

There are other multitrillion-dollar markets like financial services that cover the ocean. In those cases, not being No. 1 or No. 2 is less critical as long as you are strong in your niche—product or region.

The vision was simple, but I was still having a helluva time communicating it across GE’s 42 strategic business units. I had been thinking about how to do it better for a long time. Oddly enough, I found an answer on a cocktail napkin in January of 1983.

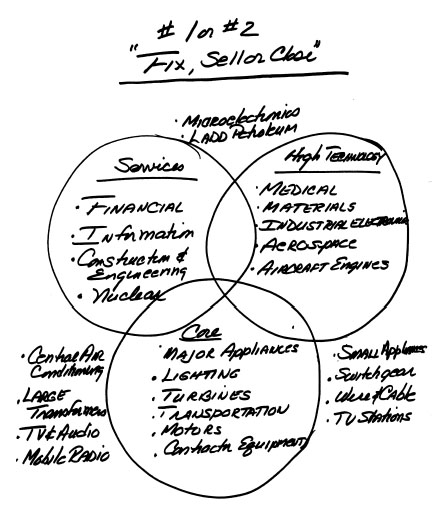

I often drive people crazy by sketching my thoughts out on paper anytime, anyplace. This time, while trying to explain the vision to my wife, Carolyn, at Gates restaurant in New Canaan, I pulled out a black felt-tip pen and began drawing on the napkin that had been under my drink. I drew three circles and divided our businesses into one of three categories: core manufacturing, technology, and services. Inside the core circle, for example, I put lighting, major appliances, motors, turbines, transportation, and contractor equipment.

Any business outside the circles, I told Carolyn, we would fix, sell, or close. These businesses were the marginal performers, or were in low-growth markets, or just had a poor strategic fit. I liked the three-circle concept. Over the next couple of weeks, I expanded it, filling in more details with my team (see below).

The chart really hit home. It was the simple conceptual tool I needed to communicate and implement the No. 1 or No. 2 vision. I began using it everywhere, and Forbes magazine eventually featured it in a cover story on GE in March of 1984.

For people who worked in businesses inside the circles, it created a certain sense of security and pride. But it raised all kinds of hell within organizations placed outside the circles, particularly in operations that were the heart of the old GE, including central air-conditioning, housewares, television manufacturing, audio products, and semiconductors. The people in these “fix, sell, or close” businesses were naturally upset.

They felt angry and betrayed. Some asked, “Am I in a leper colony? That’s not what I joined GE to become.” Union leaders and city fathers complained. This turned out to be a bigger issue than I anticipated. I knew it was something I had to come to grips with.

In the first two years, the No. 1 or No. 2 strategy generated a lot of action—most of it small. We sold 71 businesses and product lines, receiving a little over $500 million for them. We completed 118 other deals, including acquisitions, joint ventures, and minority investments, spending over $1 billion. These were peanuts, but the cultural significance of this churning was felt throughout the company, especially the sale of our central air-conditioning business.

With three plants and 2,300 employees, it was not one of GE’s larger businesses, and it wasn’t very profitable. Its sale to Trane Co. in mid-1982 for $135 million in cash raised eyebrows, because air-conditioning was right in the belly of our company. It was a division in our major appliance operations in Louisville. Yet its market share of 10 percent paled in comparison with the other GE appliance businesses.

I disliked the business the first time I was exposed to it as a sector executive. I felt it had no control of its destiny. You sold the GE-branded product to a local distributor like “Ace Plumbing.” They installed it with their hammers and screwdrivers and drove away, leaving the GE-branded air conditioners behind. How Ace installed our products and how it serviced its customers reflected directly back on GE. We were frequently getting customer complaints that had nothing to do with us. We were being tarred by something we had no control over.

Because of our low market share, our competitors had the best distributors and independent contractors. For GE, this was a flawed business. You never would have known it by the reaction we got when it was sold. It really shook up Louisville.

The air-conditioning sale to Trane reinforced my thinking that putting a weak operation into a stronger business was a true win-win for everyone. Trane was a market leader. With the sale, our air-conditioning people became part of a winning team. A month after the sale, a phone call confirmed my thinking. I called the general manager of our former business, Stan Gorski, who had joined Trane with the divestiture.

“Stan, how’s it going?” I asked.

“Jack, I love it here,” he said. “When I get up in the morning and come to work, my boss is thinking about air-conditioning all day. He loves air-conditioning. He thinks it’s wonderful. Every time I talked to you on the phone, it was about some customer complaint or my margins. You hated air-conditioning. Jack, today we’re all winners and we all feel it. In Louisville, I was the orphan.”

“Stan, you’ve made my day,” I said, before hanging up.

Through the onslaught of criticism to come, Stan’s comments helped to fortify my resolve to carry out the No. 1 or No. 2 strategy, no matter what. The air-conditioning deal also established another basic principle. We used the $135 million from its sale to help pay to restructure other businesses.

Every business we sold was treated the same way. We never put those gains into net income. Instead, we used them to improve the company’s competitiveness. In 20 years we never permitted ourselves or any of our businesses to use one-time restructuring charges as an excuse for missing an earnings commitment. We paid our own way.

From the day I wrote Reg about my qualifications for the CEO job, I adopted “consistent earnings growth” as a theme of mine. Fortunately, we had a number of strong and diverse businesses that could deliver on that pledge. We managed businesses—not earnings.

When we sold a business like air-conditioning and realized an accounting gain as well as cash, this gave us the flexibility to reinvest in or fix up another business. That’s what shareowners expected from us and paid us to do.

I liken our treatment of these gains to fixing up a house. When you don’t have the money to repair the ceiling, you put a bucket underneath the leak to catch the drips. When you find money in the budget, you fix the leak. That’s what we did at GE with much of the cash from a divestiture. We took actions to strengthen our businesses for the long haul.

Every now and then we’d get a critic, challenging how we achieved “our consistent earnings growth.” One reporter even suggested that if we took a charge to close a business in one quarter and took a gain to sell another business in the following quarter, our earnings would not have been consistent.

Duh!!! Our job is to fix the leak when we get the cash.

If you didn’t do that you’d be managing nothing. If you follow the cash, and in this case GE’s cash, you see what’s really happening in a company. Accounting doesn’t generate cash, managing businesses does.

Getting out of the air-conditioning business sparked a firestorm, but it was principally contained in Louisville. The next sale, of Utah International, was a much more difficult situation for me. Reg Jones had purchased the business for $2.3 billion in 1977. At the time, it was the largest acquisition ever—for Reg, for GE, and for all of Corporate America.

Utah was a highly profitable, first-class company that derived its income largely from selling metallurgical coal to the Japanese steel industry. It also had a small U.S. oil and gas company and large proven but undeveloped copper reserves in Chile. Reg purchased the company as a hedge against the wild inflation of the 1970s.

To me, with inflation abating, it didn’t fit the objective of consistent income growth. Its lumpy earnings clashed with my goal to have everyone feel their individual contribution counted.

GE makes its money every quarter by bringing in cash from every corner of the world, nickel by nickel. Every day, everyone’s contribution counts. As a sector executive and vice chairman, I had sat in meetings with my peers, listening as we all told how valiantly we had worked to make the quarter’s or the year’s numbers. Then, the executive in charge of Utah would stand up and unknowingly overwhelm those contributions one way or another.

“We had a strike at the coal mine,” he’d say, “so we’re going to miss our profit projection by $50 million.” All of us would stare in disbelief at the size of the number. Or he could just as easily come to the meeting and say, “The price of coal went up ten bucks, so I have an extra $50 million to toss into the pot.” Either way, Utah tended to make our nickel-by-nickel contributions seem fruitless.

I felt the cyclical nature of Utah’s business made our goal of consistent earnings impossible. I didn’t like the natural resource business, where I felt events were often beyond your control or, in the case of oil, the behavior of a cartel diminished the ingenuity of the individual.

As an aside, I believe DuPont’s acquisition of Conoco in 1981 had some of the same impact. Conoco was also purchased as a hedge against natural resource inflation—oil. But it too was large enough to make the individual efforts of many of DuPont’s business units less meaningful. Some of my Illinois graduate student friends had joined DuPont. I heard from them and others I had known in DuPont’s plastics business how personally enervating the swings in Conoco earnings could be to them. DuPont eventually spun off Conoco in 1998.

Natural resource businesses belong with natural resource companies.

Despite my feelings about Utah, I was hesitant to undo Reg’s biggest deal, which he had concluded only four years earlier. I owed everything to him. I didn’t want to appear disrespectful by selling it immediately. Before making the decision, I sent Reg a presentation laying out the rationale for the sale. I followed up with a telephone call, asking him to think about it.

Over the years, I called Reg a lot. I never did a major thing without letting him know—even though he left the board the day I became chairman.

A few days after our phone conversation about Utah, Reg called back and after grilling me for a while gave me his support. In fact, for more than 20 years, he never second-guessed me inside or outside the company.

Within a year of becoming CEO, I had privately met in New York’s Waldorf Towers with Hugh Liedtke, CEO of Pennzoil. I offered to sell him Utah. He looked at it for a while but decided it didn’t fit. He had bigger fish to fry—and he ultimately went after Getty Oil in a highly publicized takeover battle with Texaco.

I talked with other potential U.S. buyers, but found little interest.

Fortunately, my vice chairman John Burlingame had a better idea. John found what he considered the best strategic buyer for Utah, the Broken Hill Proprietary (BHP) Co. This Australian-based natural resources concern seemed the perfect fit. John contacted BHP and the company showed initial interest. He then pulled together a team with himself, Frank Doyle, and his old friend Paolo Fresco. John and Frank would strategize the discussions in the back room, while Paolo, brought back from Europe for this special assignment, would do the face-to-face negotiations.

The discussions with BHP went on for several months, complicated by size and geography. Utah’s headquarters were in San Francisco, while its assets were all over the world. BHP was based in Melbourne. After the usual ups and downs of any big deal, the teams reached a definitive letter of intent by mid-December 1982.

We were ecstatic. This was a massive property with a big price tag, and there weren’t all that many buyers for it. The sale was a huge hit for us and fit our strategy perfectly. The purchase had the same impact for BHP. The plan was to take the deal to the directors for final approval at the regular December board meeting.

The Thursday evening before that session, all the senior officers of the company and our directors were gathered in New York at the Park Lane Hotel for what had become an annual Christmas dinner and dance party. I began these social get-togethers the year before to bring management and the board closer. This time everyone at the party was pumped because of the deal. About 11 P.M., however, I noticed a staff person hurriedly escort John Burlingame off the dance floor. When the normally poker-faced John returned a half hour later, I could see he was visibly shaken—but still pretty cool.

Certainly cooler than I turned out to be after he came over to my table to report the bad news.

“Jack,” he said, “the deal’s off. I got a call from Paolo. He said that BHP just called him to say its board couldn’t go through with it. They can’t swing it financially.”

I was devastated. I was really counting on this one. The sale would have been the first big step on the strategic path I had outlined. Now, as the band continued to play, I saw all this blowing up in my face. Carolyn and I stayed till the end of the party, before returning to a suite at the Waldorf that we were sharing with Si Cathcart and his wife, Corky.

Si had quickly become a close confidant on the board. He and I stayed up until 3 A.M., talking through all the alternatives. We were somewhat in the dark, without the benefit of many details on what had gone wrong. That night, I was lower than whale manure, and poor Si had to listen to me ramble on into the wee hours.

The next morning, Burlingame and I filled in all the directors on the news. They were obviously disappointed but encouraged us to try to get the deal back on track. When I returned to my hotel room on Friday evening, I found on my bed a stuffed teddy bear with its thumb stuck in its mouth. Si had attached a note to the bear, which his wife had gone out that morning to buy. “Don’t let it get you down,” Si had written. “You’ll find a solution.”

Having been in the job just 21 months, I wasn’t sure if I had blown a big one. Si’s note hit the spot. This was the first of many times that he would prove a great help to me. He was not alone—I had enjoyed incredible board support from the first day in the job, and it would turn out to be needed on more than this occasion.

After Christmas, the Burlingame-Doyle-Fresco team went back to work on the deal. They dealt with BHP’s financial constraints by offering to take businesses out of Utah, including U.S. oil and gas producer Ladd Petroleum. This made the deal acceptable to Broken Hill, and the company bought the remainder of our Utah subsidiary for $2.4 billion in cash before the end of the second quarter of 1984. It took another year to get all the necessary government approvals. Six years later, in 1990, we sold the last piece, Ladd, for $515 million.

With the divestiture of air-conditioning and now Utah, I was feeling pretty good about our strategy and its implementation—probably a bit too good. The air-conditioning deal had upset only people in the major appliance business, where it resided. Utah didn’t cause even the slightest blip. We had held the company only a short time, and it had never really become part of GE.

The next move—our sale of GE housewares—would prove to be a lot different.

I had overseen our housewares operations for almost six years and thought it was a terrible business. Steam irons, toasters, hair dryers, and blenders aren’t very exciting products. I recall a “breakthrough” being the electric peeling wand, a device to make potato peeling a lot easier.

Not the type of “hot technology” we needed.

These products weren’t for the new GE, and we were sitting ducks for Asian imports. The industry’s manufacturers were primarily U.S. players, and all were plagued with high-cost factories. The business had low barriers to entry, and retail consolidation was diminishing any brand loyalty that existed.

I had put it outside the three circles. For me, selling this business was a no-brainer. I thought we would be losing nothing, and this would put another stake in the ground for our No. 1 or No. 2 strategy. Black & Decker had apparently heard of our view of housewares and decided it fit with their business. The company boasted a strong consumer brand in power tools and had a strong position in Europe, where we didn’t participate. Its leadership wanted to aggressively expand into a new area of business and targeted housewares.

In November of 1983, I received a telephone call from Pete Peterson, a B&D director and investment banker whom I had met on several occasions.

“Would you be interested in selling your appliance business?” asked Peterson.

“What kind of a question is that?” I said.

We played a little cat-and-mouse game for a few minutes, until Peterson said he was calling on behalf of Black & Decker’s chairman and CEO, Larry Farley.

“Okay, if you’re serious,” I said, “what can I do for you?”

“On a scale of one to five, one being you’ll never sell it, two being you’ll sell it only for a big check, and three being you’ll sell it for a fair price, where do you stand?” asked Pete.

“My major appliance business is somewhere between a one and a two,” I replied. “My small appliance business is a three.”

“Well, that’s what we’re interested in,” Pete said.

Within a couple of days, on November 18, Pete, Larry, and I were sitting in GE’s New York offices at 570 Lexington Avenue. Larry went through a long list of questions, and I answered most of them. Pete then asked straight out what I needed for the business.

“Not a penny less than $300 million, and the general manager of the business, Bob Wright, doesn’t go with the deal.”

By this time, I had enticed Bob back to GE from his Cox Cable post and put him in a holding pattern in charge of housewares. I didn’t want to lose him again. I saw Bob the next day and brought him up to date on my conversation, telling him, “Don’t worry. I’ll have a better job for you very quickly.”

It didn’t take long to hear back from Larry and Pete, who both agreed to go to the next step. While the due diligence was proceeding, an internal argument broke out over the pending sale. GE traditionalists claimed that the company benefited greatly by having our name and logo on these household products. We commissioned a quick study that showed just the opposite. The consumers’ perception of a GE hair curler or iron was okay but in no way valuable to the company. On the other hand, major appliances at that time and even today continue to rate highly with consumers.

The negotiations proceeded easily. We all trusted one another and wanted to get the deal done. Every time an issue came up during the negotiations, we resolved it easily. That would not be the last time Pete’s straightforward style and high integrity would be important to me. Within a few weeks of my first phone call, we sold the housewares business.

The ease of the business negotiation to sell housewares masked the turmoil going on inside much of GE. Employees in many of the traditional businesses were upset. The $2 billion divestiture of Utah didn’t raise an eyebrow, but selling this $300 million low-tech, tin-bending housewares business brought out unbelievable cries. I got my first blast of angry letters from employees.

If e-mail had existed, every server in the company would have been clogged up. The letters were all along the lines of “How could we be GE and not make irons and toasters?” or “What kind of a person are you? If you’ll do this, it’s clear you’ll do anything!”

The buzz around the water cooler was not good.

And there was a lot more to come, a helluva lot more.

9

The Neutron Years

In the early 1980s, you didn’t have to be in a GE business that was up for sale to wonder if Jack Welch knew what he was doing or where he was going. The turmoil, angst, and confusion were everywhere. The causes were the goal to be No. 1 or No. 2, the three circles, the outright sale of businesses, and the cutbacks now occurring in many parts of GE.

Within five years, one of every four people would leave the GE payroll, 118,000 people in all, including 37,000 employees in businesses that were sold. Throughout the company, people were struggling to come to grips with the uncertainty.

I was adding fuel to the fire by investing millions of dollars in what some might call “nonproductive” things. I was building a fitness center, guesthouse, and conference center at headquarters and laying plans for a major upgrade of Crotonville, our management development center. My take on this was that all these investments, at a cost of nearly $75 million, were consistent with the “soft” values of excellence I had outlined at the Pierre Hotel.

But people weren’t buying it. For them, it was a total disconnect.

It didn’t matter that the money I was investing in treadmills, conference halls, and bedrooms was pocket change to a company that was spending $12 billion over the same period on new plants and equipment. That $12 billion, spread across factories around the world, was invisible and considered routine.

The symbolism of the $75 million was too much for people to handle. I could understand why it was difficult for many GE employees to get it.

But I was sure in my gut it was the right thing to do.

A key supporter during this period—of spending while downsizing—was human resources chief Ted LeVino. He was the rock, a link to the past, an up-from-the-ranks GE veteran who had the respect of everyone in the system. His motives and integrity were unquestionable. I know many shaken executives sat on Ted’s couch fresh from one of their early encounters with me. Ted counseled many of the senior people who had to go. He had backed me during the selection process and, more important, knew what he was getting and believed GE needed it.

Ted’s support was important because people were out of their minds over these investments. Nothing I could say or do would ever completely satisfy the detractors or fully calm the organization’s jitters. I wasn’t going to hide. I used every opportunity to reach out. In early 1982, I began holding roundtable discussions every other week with groups of 25 or so employees over coffee. Whether administrative assistants or managers were in the room, the questions never varied.

One question inevitably dominated those sessions: “How can you justify spending money on treadmills, bedrooms, and conference centers when you’re closing down plants and laying off staff?”

I enjoyed the debates. I wasn’t necessarily winning the argument, but I knew I had to try to win people over, one by one. I’d argue that the spending and the cutting were consistent with where we needed to go.

I wanted to change the rules of engagement, asking for more—from fewer. I was insisting that we had to have only the best people. I’d argue that our best couldn’t be asked to spend four weeks away for training in cinder-block cells at a worn-out development center. Guests shouldn’t have to come to headquarters and stay at a third-class motel. If you wanted excellence, at a minimum, the ambience had to reflect excellence.

At these roundtables, I’d explain the fitness center was as much about getting people together as it was about health. A headquarters building is filled with specialists who make nothing and sell nothing. Working there is so different from working in the field, where everyone in a business can focus on and be excited by landing a new order or launching a new product. At GE headquarters, you’d park your car in an underground garage, take an elevator to your floor, and generally work in a corner of the building until the end of the day. The cafeteria was a common meeting place, but most tables were occupied by the people who worked together.

I thought a gym would provide an informal place to bring together all shapes, sizes, layers, and functions. If you will, it could be that back room of a store where people took their breaks. If investing a little over $1 million could make that happen, it was worth it. Despite my good intentions with the fitness center, people had trouble seeing the benefits in the face of layoffs.

Some of the same logic went into the decision to put up a $25 million guesthouse and conference center at headquarters, which was an island unto itself. It was in the country, some sixty miles north of New York City, off the Merritt Parkway. There was no natural place to congregate after work. Fairfield and the surrounding area lacked a decent hotel to put up employees and guests who came from all over the world. I wanted to create a first-class place where people could stay, work, and interact. The facility featured fireplaces in the lounges and a stand-up bar in the pub where everyone could mingle.

The traditionalists were shocked. I persevered because I wanted to create a first-rate informal family atmosphere and needed this ambience to get it. Everywhere I went, I was preaching the need for excellence in everything we did. My actions had to demonstrate it.

The story of Crotonville is no different. Our corporate education center was already a quarter of a century old—and unfortunately looked it. Managers were being housed in barren quarters four to a suite. The bedrooms had the feel of a roadside motel. We needed to make our own people and our customers, who came to Crotonville, feel that they were working for and dealing with a world-class company. Nonetheless, some critics began calling it “Jack’s Cathedral.”

My answers to the complaints during the early 1980s was that business is, in fact, a series of paradoxes:

• Spending millions on buildings that made nothing, while closing down uncompetitive factories that produced goods.

These goals were consistent with becoming a world-class competitor. You couldn’t hire and retain the best people, and at the same time become the lowest-cost provider of goods and services, without doing both.

• Paying the highest wages, while having the lowest wage costs.

We had to get the best people in the world and had to pay them that way. But we couldn’t carry along people we didn’t need. We needed to have better people if we were to get more productivity from fewer of them.

• Managing long-term, while “eating” short-term.

I always thought any fool could do one or the other. Squeezing costs out at the expense of the future could deliver a quarter, a year, maybe even two years, and it’s not hard to do. Dreaming about the future and not delivering in the short term is the easiest of all. The test of a leader is balancing the two. A favorite retort for at least the first ten years was, “GE and you are too focused on the short term.” That’s just another clichéd excuse to do nothing.

• Needing to be “hard” in order to be “soft.”

Making tough-minded decisions about people and plants is a prerequisite to earning the right to talk about soft values, like “excellence” or “the learning organization.” Soft stuff won’t work if it doesn’t follow demonstrated toughness. It works only in a performance-based culture.

Think of those dichotomies, those paradoxes, I was trying to get across. We needed to produce more output with less input. We needed to expand some businesses while shrinking or selling others. We needed to function as one company, but our diversity demanded different styles. And yes, we needed to treat people in a first-class way if we wanted to attract and keep the best.

The logic behind these paradoxes didn’t go far in an environment overcome with so much uncertainty. In fact, the internal upheaval was so great, it began spilling outside the company. By mid-1982, Newsweek magazine was the first publication to pick up the moniker “Neutron Jack,” the guy who removed the people but left the buildings standing.

I hated it, and it hurt. But I hated bureaucracy and waste even more. The data-obsessed headquarters and the low margins in turbines were equally offensive to me.

Soon, Neutron began cropping up almost everywhere in the media. It was as if reporters couldn’t write a GE story without using the tag. It was a painful new image twist for me. For years, people thought I was too wild, that I was too growth focused, hired too many people, and built too many facilities—in plastics, medical, and GE Credit. Now I was Neutron.

I guess that was a paradox, too. I didn’t like it, but I came to understand it.

Truth was, we were the first big healthy and profitable company in the mainstream that took the actions to get more competitive. Chrysler did it a few years earlier, but the stage was set for their actions by a government bailout and their widely publicized struggle to avoid bankruptcy.

There was no stage set for us. We looked too good, too strong, too profitable, to be restructuring. Our $1.5 billion in net income and $25 billion of sales in 1980 made GE the ninth most profitable company in the Fortune 500 and the tenth largest.

However, we were facing our own reality. In 1980, the U.S. economy was in a recession. Inflation was rampant. Oil sold for $30 a barrel, and some predicted it would go to $100 if we could even get it. And the Japanese, benefiting from a weak yen and good technology, were increasing their exports into many of our mainstream businesses from cars to consumer electronics.

I wanted to face these realities by getting more cost competitive, and that’s what we were doing.

I also saw firsthand the impact of this changing environment on many of the CEOs in the New York/New Jersey/Connecticut tri-state area. I served as a corporate chairman for the United Way campaign in the early 1980s. Time after time, as I visited with CEOs to strong-arm them for contributions, I’d hear them say, “We’d like to give it to you, but we can’t,” or, “We can’t give as much as we did in the past. Things are too tough.” This experience bolstered my notion that only healthy, growing, vibrant companies can carry out their responsibilities to people and their communities.

The costs of fixing a troubled company after the fact are enormous—and even more painful. We were fortunate. Our predecessors left us a good balance sheet. We could be humane and generous to the people we had to let go—although most probably didn’t feel we were at the time. We gave our employees significant notice and good severance pay, and our good reputation helped many find new jobs. By moving early, more jobs were available for them. It’s still true in 2001. If you were the first dot.com to cut the payroll, each of your employees had many job offers. If you were the last, your people could be in the unemployment line.

But that’s not what some thought when a “healthy” old-line company like ours was closing a steam iron plant in Ontario, California, in 1982. We learned that 60 Minutes was sending Mike Wallace and a film crew to cover it. Having 60 Minutes call to talk about a plant closing is not likely to be a pleasant event, and it ended up not being a pretty sight. Wallace reported that we laid off 825 people simply because we weren’t making enough profit and wanted to move those jobs outside the United States to Mexico, Singapore, and Brazil. He interviewed former employees who said they felt betrayed and a religious leader who condemned the plant’s closure as “immoral.”

That view was understandable then—but the facts were somewhat different. The plant made metal irons when consumers already overwhelmingly favored plastic models. We had four plants, including one in North Carolina, making plastic irons. Ontario’s product line had to be discontinued. Closing the plant was uncomfortable for everyone, but it was the highest-cost plant in our system, and we were going to be competitive.

In fairness to 60 Minutes, the program did point out that we had given our employees six months’ advance notice when the average then was only one week. Wallace also reported that we helped to fund a state-run job center on GE property to teach job-interview and other skills.

We did a lot more because our balance sheet let us. We extended life and medical insurance coverage for a year and placed 120 workers in other jobs by the time the plant closed. Nearly 600 employees would be eligible for GE pensions, and we also found a buyer for the factory that would eventually rehire many former GE employees. Despite all that, losing your job stank.

I had been in the CEO job less than a year when, in late February 1982, 60 Minutes accused us of “putting profits ahead of people.” Some critics used us as a counterpoint to such companies as IBM, which at that time still promoted the concept of lifetime employment. In fact, IBM itself launched an advertising campaign touting its nonlayoff policies in 1985. IBM’s tagline: “. . . jobs may come and go. But people shouldn’t.” Several GE managers brought the ads to our Crotonville classes and pointedly asked, “What’s your reaction to this?”

At a time when I was being routinely assaulted with the Neutron tag, those ads really pissed me off.

Sadly for the IBM people, their day would come as the company lost competitiveness.

Any organization that thinks it can guarantee job security is going down a dead end. Only satisfied customers can give people job security. Not companies. That reality put an end to the implicit contracts that corporations once had with their employees. Those “contracts” were based on perceived lifetime employment and produced a paternal, feudal, fuzzy kind of loyalty. If you put in your time and worked hard, the perception was that the company took care of you for life.

As the game changed, people had to be focused on the competitive world, where no business was a safe haven for employment unless it was winning in the marketplace.

The psychological contract had to change. I wanted to create a new contract, making GE jobs the best in the world for people willing to compete. If they signed up, we’d give them the best training and development and an environment that provided plenty of opportunities for personal and professional growth. We’d do everything to give them the skills to have “lifetime employability,” even if we couldn’t guarantee them “lifetime employment.”

Removing people will always be the hardest decision a leader faces. Anyone who “enjoys doing it” shouldn’t be on the payroll, and neither should anyone who “can’t do it.” I never underestimated the human cost of those layoffs or the hardship they might cause people and communities. To me, every action had to pass a simple screen: “Would we like to be treated that way? Were we fair and equitable? Can you look at yourself in the mirror every day and say yes to those questions?”

As a company, we could look at ourselves in the mirror when it came to softening the rough edges of radical change. The speech I had to give 1,000 times was, “We didn’t fire the people. We fired the positions, and the people had to go.”

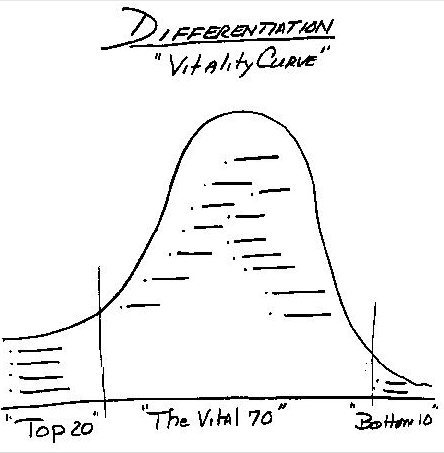

We never resorted to “across the board” cutbacks or pay freezes, two old management favorites to reduce costs. Carried out under the guise of “sharing the pain,” both actions are examples of people not wanting to face reality and differentiation.

That’s not managing or leading. Edicts to impose a uniform 10 percent layoff policy or a wage freeze undermine the need to take care of the best. In the spring of 2001, several economy-impacted GE businesses, such as plastics, lighting, and appliances, were downsizing. Meanwhile, some businesses, such as power turbines and medical, couldn’t add people fast enough.

Unfortunately, in the 1980s most of GE’s employment levels were headed downward. We went from 411,000 employees at the end of 1980 to 299,000 by the end of 1985. Of the 112,000 people who left the GE payroll, about 37,000 were in businesses we sold, but 81,000 people—or 1 in every 5 in our industrial businesses—lost their jobs for productivity reasons.

From the numbers, you could make the case that there was either a Neutron Jack or a company with too many positions. I naturally took comfort in the latter, but the Neutron tag still got me down. I was fortunate to find remarkable support that got me through it—at home, in the office, and in the boardroom. I’d come home obviously a little down from the experience. Carolyn would always be supportive, no matter how tough the press. She always ended a conversation with, “Jack, you have to do what you think is right for everyone.”

In the 1980s, the massive nature of the changes at GE would have been impossible without a core of strong supporters inside the company. Once rivals and now partners, my two vice chairmen John Burlingame and Ed Hood backed all the moves. So did two of the most powerful staff players at headquarters, HR chief Ted LeVino and chief financial officer Tom Thorsen. Tom and I were thick as brothers in Pittsfield and happy to be reunited in bigger jobs at headquarters. Larry Bossidy, whom I brought to Fairfield in 1981 to take over a newly created materials and service sector, had become my sounding board, confidant, and close friend.

Without strong backing from the board, these changes couldn’t have happened. Board members heard all the complaints, sometimes from angry employees who wrote critical letters directly to them, and they read all the negative press. From day one, however, the board never wavered.

When I first became CEO, Walter Wriston went around New York telling everyone he met that I was the best CEO in the history of the company—even before I did anything. It sure felt good to hear that, especially during my Neutron days. He was a stand-up, gutsy guy who kept telling me to do what I had to do to change the company.

Still, the pressure to avoid some of these tough decisions was considerable. The lobbying wasn’t only internal—the calls came in from mayors, governors, state and federal legislators.

Once, on a scheduled visit to the Massachusetts state house in 1988, I met with Governor Michael Dukakis.

“It’s a great thing that you’re in the state,” said Dukakis. “We’d really like to see you put more work here.”

The day before my meeting, our aircraft engine and industrial turbine plant in Lynn, Massachusetts, had distinguished themselves once again by being the only GE union in the chain to reject our new national labor agreement.

“Governor,” I said, “I have to tell you. Lynn is the last place on earth I would ever put any more work.”

Dukakis’s aides were shocked. There was a long silence in the room. Everyone was expecting me to make some reassuring comment about our commitment to employment and possible expansion in Massachusetts.

“You’re a politician and you know how to count votes. You don’t put new roads in districts that don’t vote for you.”

“What do you mean?” he asked.

“Lynn is the only local in all of GE that has rejected our national union contract. They seem to do this as a ritual over the years. Why should I put work and money where there is trouble, when I can put up plants where people want them and deserve them?”

Governor Dukakis chuckled. He instantly understood the point and sent his labor representative to Lynn to improve things. Progress has been slow to say the least, but Lynn did vote for the national contract in 2000.

I took another solid hit in early August of 1984 when Fortune magazine put me at the top of its list of “The Ten Toughest Bosses in America.” This was a case where being No. 1 or No. 2 wasn’t something you were looking for. Fortunately, the article had some good things to say as well. One former employee told the magazine that he had never met someone “with so many creative business ideas. I’ve never felt that anybody was tapping my brain so well.” Another actually credited me “with bringing to GE the passion and dedication that characterize the best Silicon Valley start-ups.”

I liked all that, but the positive reactions were overshadowed by comments from “anonymous” former employees who said I was very abrasive and didn’t tolerate “I think” answers. “Working for him is like a war,” claimed another unidentified person. “A lot of people get shot up; the survivors go on to the next battle.” The article claimed that I attacked people almost physically with questions, in the words of the writer, “criticizing, demeaning, ridiculing, humiliating.”

In truth, the meetings were different from what people were used to. They were candid, challenging, and demanding. If former managers wanted a reason why they didn’t cut it, there were plenty of ways to spin the story.

I got the article as I was leaving the office for California to spend a weekend at the Bohemian Grove as the guest of director Ed Littlefield. I shared the story with Ed, who shrugged it off.

I couldn’t get it out of my mind. The story made it a long weekend. The net effect of all this publicity was that the “Neutron Jack” and “Toughest Boss in America” labels would stick for some time.

The ironic thing was that I didn’t go far enough or move fast enough. When MBAs at the Harvard Business School in the mid- 1980s asked me what I regretted most in my first years as CEO, I said, “I took too long to act.”

The class burst out laughing, but it was true.

The facts were that I was just too hesitant to break the glass. I waited too long to close uncompetitive facilities. I took too long to take apart the corporate staff, keeping on economists, marketing consultants, strategic planners, and outright bureaucrats much longer than I needed to. I didn’t blow up our sector structure until 1986. It was just another insulating layer of management and should have been cut the moment the succession race was decided.

The seven executives in these sector jobs were the best people we had. They should have been running our businesses. I was wasting them in these oversight positions. We promoted our best executives to those jobs, and in turn those jobs made some of our best people look bad. Once we blew it up, we quickly discovered something else. Without the sector layer, we got a much better look at the people really running the businesses.

It changed the game. Within months, we could see clearly who had it and who didn’t. Four senior vice presidents left the company in mid-1986. It was a huge breakthrough.

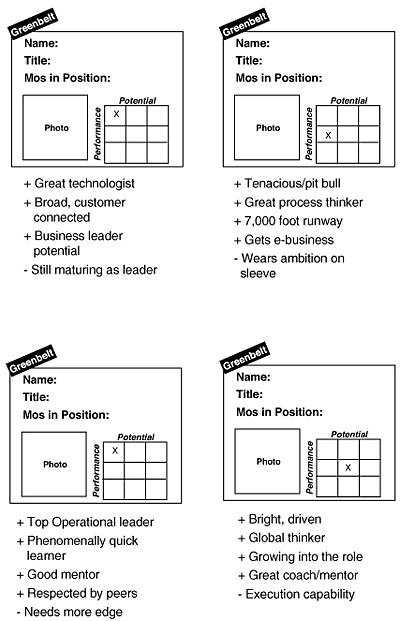

While the media focused on the layoffs, we focused on the “keepers.” I could talk my face blue about facing reality, or being No. 1 or No. 2 in every business, or creating an organization that thrived on change, but until we got the right horses in place, we didn’t get the traction we needed to truly change the company. I shouldn’t have wasted so much time on the resisters, hoping they’d “buy in.”

When we finally got the right people in all the key places, the game changed quickly. Let me illustrate what putting the right person at the top can do. I can’t think of a better example than our appointment of Dennis Dammerman as chief financial officer in March of 1984.

If you had asked thousands of employees at that time to come up with a list of five folks who would succeed Tom Thorsen as CFO, none would have named Dennis because he was so far down in the financial hierarchy.

Tom and I always had a complex relationship. I loved his brains, his cockiness, and his companionship. In spite of his outwardly flamboyant manner and his great support for where we were going, he saw himself as the protector of the strongest functional organization in the company.

Ironically, he was also the sharpest critic in the company, tough and decisive about everything and everyone, including me. Yet, when it came to finance, he couldn’t bring himself to step on the function’s sacred turf. We had many conversations about this but could never agree. Tom moved on to become CFO of Travelers.

With 12,000 people strong, finance had become too large and too entrenched a part of the bureaucracy. Most of the “nice to know” studies originated in the finance function, which at that time spent $65 million to $75 million a year on operations analysis alone.