CHAPTER 1: 1853–1868

Introduction of Railway Technology, the Shōgunal

Railway Proposal, and the First Railway Concession

Compared to 1643, the Western world had changed quite a bit by 1820, while, relatively speaking, Japan had changed but little. Britain was well on the way to creating its Empire, having recently secured a position of primacy in India, which would serve as the principal base from which further Asian trade and colonial expansion would be conducted. The political institutions and boundaries of Europe had just been revised by the convulsions of the Napoleonic Wars and the settlement issuing from the Congress of Vienna, which ceded to Britain small Dutch colonial holdings in the Cape of Good Hope at the southern tip of Africa, a very necessary re-supply point on any ocean voyage from Europe to the Far East. Thus, Britain found her position to trade with Asia markedly improved. Russia was a rising power that was just starting to expand development of the far eastern reaches of its territories, and in the western hemisphere the United States was a fledgling nation that had yet to prove itself capable of being, much less gaining acceptance as, a world power. The first effects of the industrial revolution were being felt, spurred in part by the technology of stationary steam engines used in England starting in the 1790s to power mine hoists, mine pumping stations, and textile machinery. Success in these areas gave rise to the application of the reciprocating steam engine to naval propulsion and in the UK to hitherto horse-drawn mine-car rail technology, starting in 1803 to1808 with the world’s first two railway locomotives constructed by the Cornishman Richard Trevithick. The success of the primitive and inefficient locomotive was at least such that, for a brief period when the Napoleonic Wars and failed crops (due to the volcanic ash-dimmed “year without a summer,” courtesy of Indonesia’s Mount Tambora) increased the price of feedstock for horses, the fledgling engines proved to be more cost-effective than horsepower. In other spheres, the economic benefits to be gained from industrialization were starting to be appreciated on a mass level, as were the economic benefits to be gained from trade in the products of this new industrialization.

As early as the 16th century, mining enterprises in the German principalities had started to use wooden rails to guide flange-wheeled mine carts hand-pushed by miners, but the technology’s greatest application occurred in the coal mines around Newcastle in the United Kingdom commencing in the latter half of the 17th century. The mine tracks built were crude affairs only a few miles long—just long enough to transport coal from the pithead to the closest navigable waterway where it could be loaded onto ships. Operation was by horse and gravity. By 1825, the two technologies of rail-borne transport and steam power had converged and had matured to the point that Great Britain gave the world the first commercial common-carrier railway to undertake a scheduled passenger service (not just coal traffic) when the Stockton and Darlington Railway in northern England was opened. Passengers were a bit of an experimental venture and were hauled daily in horse-drawn stagecoaches or omnibus under arrangement with several independent operators, unlike a railway as we have come to know it. In theory, anyone owning a team of horses and one or more flanged-wheeled wagons conforming to the railway’s gauge was allowed, through arrangements with the company, to “train their waggons” over the line on payment of a fee much like a toll fee on a turnpike; as canal boat owners of the day were allowed to use a canal. In practice few took advantage of this, except for a number of businesses along the line for their freight needs and stagecoach owners for passenger service. This gave rise to traffic congestion (the Stockton and Darlington operated much like a common toll-road, not attempting to regulate traffic movement) since the trains of carts couldn’t pull over to the side of the road or pass, as could be done on regular roads, and as drivers not employed by the company did not always coordinate their movements to correspond with places on the line where passing sidings had been installed. This problem was not lost on the innovators of the day. Indeed, one of the company records indicates, “The Committee [Board of Directors] found great inconvenience by Carriages traveling on the Railway at different speeds, and being convinced of the necessity of adopting one uniform rate of traveling, have had several interviews with the Merchandise Carriers for the purpose of inducing them to adopt the leading of Merchandise by [the company’s] locomotive engines instead of horses as heretofore.” [Emphasis supplied]

Five years later saw the birth of what was the first full-fledged railway in the modern sense of the term. Horse traction would not be used: steam locomotive propulsion was to be employed from inception. The only trains permitted on the line were those operated by the railway company itself, subject to traffic control under direction of the company. By that time, George and Robert Stephenson had built an efficient steam locomotive, the design of which differed from modern steam locomotives arguably in only three or four major technical aspects. The line was the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, opened on September 15, 1830 by the Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, the celebrated “Iron Duke,” not by virtue of his railway advocacy, nor victory at Waterloo, but due to his unpopularity that required he shield his windows with iron shutters. Despite a long preceding and gradual development, it can still be said generally that the inauguration of the Liverpool and Manchester on that September 15th marks the birth, not of railways per se, but of the Railway Age, for after the success of the Liverpool and Manchester, railways were no longer an unproven experimental technology, but were thenceforth increasingly accepted as “proven and profitable.”

Meanwhile back in Japan, Dutch trading ships in strictly regulated quotas continued to come and go from the Nagasaki Deshima. Trade and trade ships had improved in the interceding 200 years, the age of the clipper ship was dawning, and Europe, particularly Great Britain, was becoming increasingly hungry for markets for the new mass produced products resulting from its recent industrialization. By contrast, little had changed in Japan. At the most restrictive point in 1715, the number of Dutch ships allowed to enter Japan—the trading capacity of the entire Western world—was limited to 2 ships per year. Even ships from neighboring China had been limited to 25 ships a year by 1736. Holland, China, and Korea (which was permitted to trade only with the island of Tsushima midway between the two countries) were the only countries with which Japan had any contact whatsoever, let alone formalized trade arrangements. Knowledge of Western technology was slowly trickling into the country by means of whatever books or sages were brought by the annual Dutch East India Company ships that were allowed to drop anchor at the Deshima, and by means of the annual Fusetsu-sho, that the Opperhoofd from Nagasaki was required to make annually to the Shōgun in Edō. The report covered not only Deshima trade matters, but gradually developed into an annual briefing on world affairs occurring beyond Japan’s shores, as digested by the Opperhoofd. Official policy towards contact with the West vacillated with glacial speed: a series of earlier edicts banning Western learning and dissemination of Western texts and teachings was relaxed in 1720 by the Shōgun Tokugawa Yoshimune (with the exception of books on the topic of Christianity), but 1839 marked another crack-down, which came to be known as the “Imprisonment of the Companions of Barbarian Studies.”

Against this backdrop, the inevitable Western trade overtures to Japan were renewed as industrial expansion and mass production lead to an increased desire for trade, and improved methods of transportation lead to the means to deliver the goods. As an incentive to Japan, the western nations of the early 19th century often used western technology as a lure to encourage opening the country and establishing trade relations. Among the first suitors to appear were Russians, relative newcomers to Japan, who made overtures in 1792, 1798, 1804, 1811, and 1814—the most memorable of which was the Rezanov mission of 1804—but all ended in failure. The British tried to re-establish relations in 1797, 1801, 1803, 1808, 1810, 1813, 1818, and 1824, with more persistence and determination, but met with similar failure. A nation new to Japanese shores arrived in 1797 when the Yankee captain Robert Stewart sailed into Nagasaki harbor onboard the American ship Eliza. That attempt was also a failure, despite his ostensibly acting as a neutral party on behalf of the Dutch, whose merchant marine was confined to port due to a British blockade; the Dutch Government being allied with the French in the throes of the Napoleonic upheavals. Further unsuccessful American attempts occurred in 1806, 1837, and 1846. Concurrently, a period of episodic confrontations and incidents had been unfolding with British and Russian warships appearing in Japanese waters together with increasing confrontations with Russians in the Sakhalin Islands, all culminating in the 1825 Shōgunal Edict for the Repelling of Foreign Ships out of fear of further contact. At the time, the issue of taking on food, fresh water, and firewood or coal was of the highest importance to trade ships and trading nations, as ships’ stores would have been depleted after long trans-oceanic voyages which could take months, but temporary stops in Japan, even for re-supply purposes only, were forbidden. The use of Japan as a re-supply stop was not vitally important to European traders, for whom Japan was likely the last port of call at which to collect commodities before they turned and set sail back for home, but it was very critical to America, because of course it would be the first accessible re-supply point for the famous China Clippers or other slower Yankee ships after a long Pacific crossing (on a voyage that could take up to ten months from New York or Boston). Since California had yet to become a U.S. possession and re-supply point, the young republic’s interest in being able to use Japan as a re-supply point was all the more acute.

Matters proceeded along in this fashion, until a domestic event occurred that was to seriously loosen the Bakufu’s1 grip on power: the great Tempō Famine of 1833–1836. At the worst of the famine, the rice harvest was only one-third its usual level in some regions. Hundreds of thousands of souls are estimated to have perished. The Tokugawa régime found itself relatively helpless to relieve matters and public resentment ran both high and deep. The weakening of the Bakufu’s support at a time of increasing foreign pressure did not bode well for continuation of the régime.

While the 1830s saw the increase in a new economic pursuit in Pacific waters: whaling that brought more and more ships into Japanese waters and into confrontational status with the Tokugawa régime bent on repelling them, the 1840s saw an easing of the tension, domestically with the Tempō Reforms and also internationally with the revision of the Edict for the Repelling of Foreign Ships with the humanitarian concession that it was at least permissible to provision foreign ships with the basic necessities of food, water, and firewood. 1844 saw the appearance of a Dutch warship in Nagasaki harbor carrying a demand from its sovereign King William II that Japan open its markets to foreign trade. The US Navy Commodore Biddle aboard the Columbus made another call in 1846 to importune again on behalf of his government. Both were rebuffed amid growing concern that this policy would not be viable indefinitely.

All too soon for the Japanese, a squadron of four “Black Ships” of the US Navy appeared on the horizon; side-wheel paddle steamer warships dispatched in the waning days of Millard Fillmore’s presidency under the command of Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry. Perry’s frigates appeared off the coast of Shimoda, Izu province, on the southern tip of the eponymous peninsula, southwest of the Shōgunal capital of Edō, on July 8, 1853 on full battle alert. Perry delivered a message from the United States Government asking for the establishment of trade relations. His squadron stayed only long enough to receive assurances that his message would be delivered to competent authorities, and Perry advised the Japanese that he would set sail to China in order to give the government adequate time to consider its reply and would return the next year to have it.

One month after Perry had left his first calling card, ships under the command of E. V. Putyatin of the Imperial Russian Navy dropped anchor off Nagasaki on August 2, 1853 bearing gifts as an enticement, among which was a small alcohol-fired model of a railway steam locomotive and train about the size of a large toy. Putyatin is said to have run this model train on the deck of his flagship, the Pallada. It was seen by Tanaka Hisashige from the Kyūshū town of Kurume. Tanaka, who would go on to form one of the companies that evolved into the present-day Toshiba, and he eagerly set about making an imitation, which was completed shortly thereafter. This was the first operating model steam locomotive built in Japan. It may still be seen in the Saga museum, and gives some idea how the Putyatin model must have appeared.

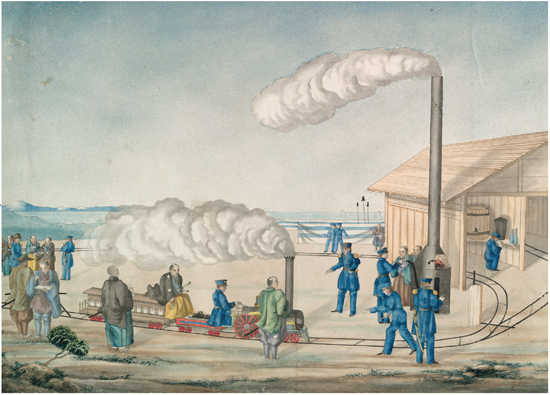

When Perry reappeared in February 1854 to receive his demanded reply, his squadron of Black Ships had increased to a task force of seven—a fact not lost on the Japanese. This time Perry did not return to the Izu peninsula, but chose an anchorage in closer proximity to the capital: the Uraga Straits region of the Miura peninsula, uncomfortably close to Edō at a place he called “Mississippi Bay,” a name which for many years stuck with and was used by the foreign residents destined to settle there. Along with him, Perry had brought gifts from the Republic to the Shōgun. Among those gifts was a 610mm (two foot) gauge fully functional model of a 4-4-0 Norris locomotive, a tender, passenger car, and one mile of circular track, which his crew set up on the beach at Mississippi Bay, to demonstrate to the Shōgunal representatives, among whom was Kayama Yezaemon, (described in Perry’s report as the “Governor of Uraga”) and “Prince Hiyashi” (Hayashi Daigakonokami, an official who would have been the equivalent of a modern-day Minister of Education).2 Judging from the gauge, and scaling proportionally, this locomotive was perhaps a one-quarter scale model, of a size large enough to have hauled 3 or perhaps 4 adults behind it on its train, about the size of amusement park railways for small children one finds today in city parks or at small fairs.

The first Westerners bringing Western carriage building technology to Japan were disappointed by the amazing lack of horses with which to pull any domestically built products of their labors. The Japanese soon learned the Western skills and axles, bearings, and other iron work parts were beginning to be imported or were starting to be produced domestically. The first jinrikisha (lit. man-powered car) appeared in Yokohama around 1868. Various Japanese and Western claimants vie for the honor of having invented it. Its use spread quickly throughout Asia, and became a form of transport for hire, for distances both short and long, of the relatively well-off traveler of the day: the rental car of the Meiji era. Their appearance fascinated Western visitors so much that they became a standard symbol of the Far East and thousands upon thousands of photographs such as this one were made for the tourist market. The cape made of straw is a traditional Japanese raincoat, the straws serving the same purpose as the fringe on an American cowboy’s buckskin jacket: channeling water to run off the garment before it could soak in.

It is difficult to say with any certainty how aware the Japanese were of railway technology at the time of Perry’s visit. The Dutch Opperhoofd Joseph Henry Levyssohn had mentioned a French plan to build a portage railway across the Panama isthmus to the Shōgun in his 1846 Fusetsu-sho. (The French builders defaulted in 1848, but the scheme was taken up by Americans in 1850 and the railway was completed in 1855.) The 1844 Dutch book Eerste Grondbeginselen der Naturkunde (First Principles of Natural Science), which contained passages treating on steam locomotives, is thought to be the first book on the subject of railways to enter Japan, and by 1854 had been translated into Japanese under the title: Enzei Kiki Jutsu (A Description of Notable Machines of the West).

It is also known that a Japanese fisherman, Nakahama Manjirō, along with other crewmates had been shipwrecked in 1845 and rescued by a homeward-bound American ship. Nakahama rode a train while in the US and on his return to Japan in 1851 gave an account of this (the Hyoson Kiryaku) to official interrogators of the Lord of Tosa province. The restriction barring return of foreign-traveling Japanese had been somewhat relaxed by then but was still illegal giving rise to a criminal investigation and official report. Nakahama’s testimony about the shipwrecked sailors’ travels was subsequently transcribed and reads as follows:

“After landing they saw many strange vehicles called ‘reiroh’ [i.e. railroad]. (There were many such vehicles in the United States; Manjiro said he had ridden on one before.) The railroad ran on coal. An 18-square foot iron box enclosed a strong coal fire and the accumulated steam was released through an iron pipe. The steam turned the wheels and propelled the massive vehicle at a high speed—turning exactly the same way as the wheels of a steamboat. Some 23 or 24 iron boxes were connected in succession. People settled in a box, put their possessions on the rack above and sat underneath. They could look at the scenery out of windows—three on the right side, three on the left—all fitted with glass. If you looked out the windows, all things slanted sideways; and it ran so fast that nothing remained in sight for long. It was a rare sight. The railroad’s path lay where there were no mountains, and iron rods were laid on the ground without a break, for hundreds of miles, so that the railroad could run over them.”

Naturally, Perry was keenly interested in ascertaining how knowledgeable about the West his hosts were, as the following passage from the official report of his expedition makes clear:

“Their inquiries in reference to the United States showed them not to be entirely ignorant of the facts connected with the material progress of our country; thus, when they asked if roads were not cut through our mountains, they were referring (as was supposed) to tunnels of our railroads. And this supposition was confirmed on the interpreter’s asking, as they examined the ship’s engine, whether it was not a similar machine, although smaller, which was used for traveling on the American roads. They also inquired whether the canal across the isthmus was yet finished, alluding probably to the Panama railroad which was then in progress of construction. They knew, at any rate, that labor was being performed to connect the two oceans, and called it by the name of something they had seen, a canal.... The [ship’s steam] engine evidently was an object of great interest to them, but the interpreters showed that they were not entirely unacquainted with its principles... There can be no doubt, that however backward the Japanese themselves may be in practical science, the best educated among them are tolerably well informed of its progress among more civilized or rather cultivated nations.”

After an inspection tour of the squadron’s ships, it was time to present the official gifts. The description of the demonstration of the little Norris locomotive that is contained in Perry’s official report begins:

“The day agreed upon had arrived (Monday, March 13 [1854]) for the landing of the presents, and although the weather was unsettled, and the waters of the bay somewhat rough, they all reached the shore without damage... The presents filled several large boats, which left the ship escorted by a number of officers, and a company of marines, and a band of music... The presents having been formally delivered, the various American officers and workmen selected for the purpose were diligently engaged daily in unpacking and arranging them for an exhibition. The Japanese authorities offered every facility... a piece of level ground was assigned for laying down the circular track of the little locomotive, and posts were brought and erected for the extension of the telegraph wires... The telegraphic apparatus, under the direction of Messrs. Draper and Williams, was soon in working order, the wires extending nearly a mile, in a direct line, one end being at the treaty house, and another at a building expressly allotted for the purpose. When communication was opened up between the operators at either extremity, the Japanese watched with intense curiosity the modus operandi, and were greatly amazed to find that in an instant of time messages were conveyed in the English, Dutch, and Japanese languages from building to building. Day after day the dignitaries and many of the people would gather, and, eagerly beseeching the operators to work the telegraph, would watch with unabated interest the sending and receiving of messages.

Nor did the railway, under the direction of Engineers Gay and Danby, with its Lilliputian locomotive, car, and tender, excite less interest. All the parts of the mechanism were perfect, and the car was a most tasteful specimen of workmanship, but so small that it could hardly carry a child of six years of age. The Japanese, however, were not to be cheated out of a ride, and, as they were unable to reduce themselves to the capacity of the inside of the carriage, they betook themselves to the roof. It was a spectacle not a little ludicrous to behold a dignified mandarin whirling around the circular road at a rate of twenty miles an hour, with his loose robes flying in the wind. As he clung with a desperate hold to the edge of the roof, grinning with intense interest, and his huddled up body shook convulsively with a kind of laughing timidity, while the car spun rapidly around the circle, you might have supposed that the movement, somehow or other, was dependent rather upon the enormous exertions of the uneasy mandarin than upon the power of the little puffing locomotive which was so easily performing its work.”

This woodblock triptych shows one of the first trains on the Shimbashi line, drawn by one of the two Dubs locomotives that were among the first ten imported to Japan. The view shows the point just south of the Takanawa causeway where the line turned inland at Shinagawa station, running under a bridge over which the Tokaidō highway passed. It gives a good indication how the Japanese of the day viewed the curiosity of the new railway technology and also evidences what the traffic density on the nation’s busiest highway was at that time.

The first two dispatches from the event reported in the New York Times recounts that the Japanese were “delighted and astonished with” the miniature railway, characterizing it and the telegraph as “happy hits,” and adding that “... at first the Japanese were chary of venturing into the car, but after a single trial there was much good humored competition for places.”

By the end of his return visit in February and March, 1854, Perry had made clear what the consequences of refusal would be. One of the early Japan scholars, Basil Chamberlain, put it succinctly: “To speak plainly, Perry triumphed by frightening the weak, ignorant, utterly unprepared and insufficiently armed Japanese out of their senses. If he did not use his cannon, it was only because his preparations for using them and his threats of using them were too evidently genuine to be safely disregarded by those who lay at his mercy. His own ‘Narrative’ is explicit on that point.” As a result, Perry succeeded in obtaining an agreement in principal from the Shōgunal Government to establish trade relations, which resulted in a provisional treaty; the so-called “Kanagawa Treaty,” soon to be followed by a more formalized treaty thereafter negotiated and concluded by the first diplomatic envoy to Japan from any Western power, the American Townsend Harris. The “Harris Treaty” of 1856 was the first of many trade treaties to follow as every Western trading power of the day followed suit, demanding a similar status to that which the US had obtained. At the time, Western knowledge of Japanese political affairs was so unsophisticated that the exact nature and nuances of the relationship between Shōgun and Emperor were not widely understood. The Bakufu itself was at a loss to come upon a term that would suitably express the Shōgun’s stature to the foreigners. Eventually, all concerned borrowed a term which had lately been employed by the British in several treaties recently concluded with China in the aftermath of one of the Opium Wars, and the Shōgun took to styling himself the “Great Prince” or Tai-kun-shu 大君主. The Westerners first arriving on the shores of Japan generally abbreviated this name and Anglicized its spelling, thereafter often referring to the Shōgun in shorthand fashion as the Tycoon.

Matthew Calbraith Perry successfully accomplished the “opening of Japan,” in large part through threat of force, during his two visits to Japan in 1853 and 1854, thereafter forever altering the course of its history.

Japan had been coerced under threat of armed intervention to open its doors, but initially, trade was confined to certain ports only (towns like Yokohama, Kōbe, Hakodate, and Nagasaki, which came to be known as “Treaty Ports”) and foreigners were required to have a special passport to travel to the interior of the country anywhere outside the confines of the Treaty Ports.

* * * * * * * * *

There is little historic record of railway activities for the next ten years in Japanese history but by 1865 enough rails, flanged wheels, and railway hardware had been imported that Japan’s first railway that accomplished a commercial purpose was in operation. This was a short mining railway that was constructed to move coal from the mines of newly discovered coal deposits at a locale known as Kayanuma in Hokkaidō to a navigable transshipment point. The venture came to be known as the Kayanuma Tankō Tetsudō 茅沼炭坑鉄道 (tankō means coal mine and tetsudō, literally “iron way,” means railway). Little is known of the line or its workings, save for the fact that it was worked on a “horse and gravity” principle, in the time-honored tradition of the first coal mine rail lines around Newcastle 200 years before.

Nagasaki in 1865 was quite a different town than it had been ten years before. Foreigners were no longer Dutch and Chinese only and were no longer confined to the Deshima. A newly arrived Scottish trader by the name of Thomas Blake Glover founded the firm T. B. Glover and Co., which is said to have imported from Great Britain a small 762mm (2’ 6”) gauge steam locomotive and to have demonstrated it on a test track along the Nagasaki Bund (as the waterfronts in Far Eastern treaty ports were becoming known) between Lot numbers 1 and 10 in the foreign resident’s quarters in hopes of inspiring “railway fever” to Glover’s profit among the Japanese. Some authorities question this, but if the reports are to be believed, this was the first locomotive in Japan that was not a model and was capable of actual commercial activity, despite the fact that there is no confirmation that it ever performed revenue earning service. Again, very little is known about this demonstration railway, but fittingly the first fully-functional locomotive in Japan was named the Iron Duke and, if reports are to be believed, then the Iron Duke inaugurated the Railway Age to Japan, a symbolism perhaps not lost on Glover. There is brief mention of this event in The Railway News of London, July 22, 1865, “A railway, with locomotive engine and tender, is in operation on the Bund at Nagasaki, and excites a great deal of attention among the Japanese, who come from far and near to see it.” Thomas Glover’s house still stands in what is now a park in Nagasaki and is in fact the oldest Western-style residence in Japan, but what became of the Iron Duke is not known. There is, however, a small, tantalizing reference to Glover & Co. having conveyed a steam engine as part of the equipment package sold to the Japanese Government when it commenced construction of its first modern Imperial Mint in Ōsaka shortly thereafter. Whether this was a stationary engine to power the mint machinery or the elusive locomotive is not known, although it is known that in the very earliest days of the Ōsaka Mint’s operation, there was a small “tramway” line that was laid between the mint proper and Ōsaka station. There is one tantalizing further reference to this locomotive to be found in a 1922 French article, which relates that the locomotive was “Vendue, dit-on, à des marchands d’Osaka.” (“Sold, they say, to Ōsaka merchants.”)

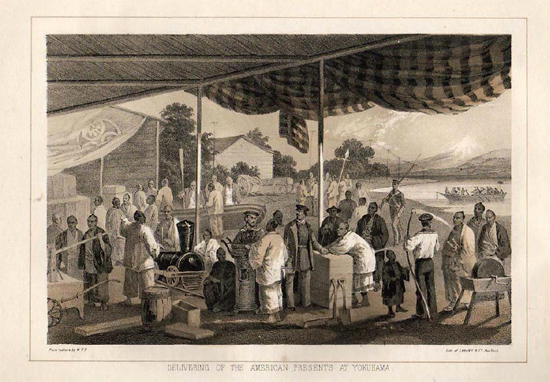

Within sight of Mt. Fuji, the miniature Norris locomotive brought by Commodore Perry’s Expedition in 1854 as a gift of the United States is unloaded among the other gifts brought ashore on the beach of Mississippi Bay, just south of Yokohama. The scene is more likely an arranged composition from the hands of the Perry Expedition’s artist than an actual depiction.

By the time Glover was demonstrating the Iron Duke in Nagasaki, Shōgunal power had deteriorated almost completely and change was taking hold. By dint of sheer military power, Western nations had succeeded in forcing a series of decidedly unequal treaties upon the Japanese Government that the Bakufu did not have the military power to resist, an example of which were the notoriously exploitative extra-territoriality clauses exempting foreign nationals from Japanese law when on Japanese soil (subjecting them instead to “consular courts” in the treaty ports presided over by foreign consuls or judges), but providing no reciprocal exemptions to Japanese citizens abroad. Superficially the strategy of the Shōgunate, then nominally in the hands of a mere teenager, Tokugawa Iemochi, whose reign was destined to be among the more inept of the Tokugawa line, seemed to be a policy of sufferance and containment, while taking the first tentative steps toward modernization and adoption of Western technologies. Discontent with the régime was widespread. Reactionary daimyō advocated outright expulsion of all foreigners and a return to Japan’s isolationist policy. More farsighted and progressive daimyō argued that radical industrialization and commensurate strengthening of Japan was the only viable chance Japan had to escape annexation and colonization by European powers who were making just such moves across the Yellow Sea on the Asian mainland at that very time, in what has come to be known as the Opium Wars and the French Indo-Chinese Wars. Unhappy with the Shōgunate’s perceived and actual weakness via-à-vis Western nations and for other reasons, the other daimyō began to put pressure on the Tokugawa Shōgunate, which found itself caught between polarized daimyō and Western Powers on its doorstep in the heyday of colonization, with little room to maneuver.

To the forefront of the anti-Tokugawa cause came the Chōshū domain, at the southwestern-most tip of Honshū, across the straits of Shimonoseki from Kyūshū. (Chōshū was the Sinicized name of Nagato province, roughly the western half of today’s Yamaguchi prefecture, a domain historically antagonistic to the Tokugawa régime.) Resentful of Western encroachments decidedly to the disadvantage of the Japanese people, the Chōshū domain started militating against foreign presence in Japan and in favor of restoration of political power to the Emperor. In 1863 it orchestrated a series of anti-Western and anti-Shōgunal confrontations, not without tacit encouragement from the Imperial court at Kyōto. As a result of attacks on British ships in 1863, for which attacks the Chōshū domain was unilaterally punished by a British Royal Navy bombardment and destruction of Chōshū forts at Shimonoseki the following year, the Japanese Government was saddled with an Indemnity of $3,000,000 Mexican Dollars, known as the Shimonoseki Indemnity.3 After a coup attempt in 1863, and an uprising in the capital staged in 1864, the Emperor felt obliged to call on the Shōgun to restore order to the realm in 1864 by mounting an expedition to put down the unruly Chōshū daimyō. To the surprise of some, the results were not altogether successful for the Shōgunate, such that 1866 saw the powerful Kyūshū daimyō fiefdom of Satsuma (another domain with historic antagonism toward the Tokugawa Shōgunate since the days of its defeat at the hands of Hideyoshi) joining its neighbor Chōshū in an alliance, again using the restoration of political power to the Emperor and total expulsion of foreigners (the so-called sonno jōi movement) as a rallying point.

This painting is one panel from a scroll by an unknown (presumably Japanese) artist depicting the demonstration of the Norris locomotive that Commodore Perry brought as one of his gifts. The train, with a Japanese dignitary aboard, approaches a turnout with a lever-operated switchstand controlling the route between the main loop and apparently a storage siding leading into the building, beside which a gift forge has been erected for demonstrations of Amerian smithing technology. A high ranking American officer appears wearing a cocked hat at far left. The scroll was at one time in the collection of Wang Zhiben, a Chinese art scholar who taught in Japan in the Meiji era.

For a brief period, in 1865–1866, a proposal for construction of a railway to run between the Imperial Capital of Kyōto and Ōsaka was pressed by the daimyō and future leading industrialist Godai Tomoatsu of Satsuma (although an acquaintance of Glover, Tomoatsu made his proposal with Belgian backing) as a means of being able to speed troops from the Chōshū and Satsuma domains in the south in the event of an emergency to “defend” the Emperor from colonizing foreigners, first via steamer to Ōsaka and thence by rail to Kyōto. Understanding all too well that rallying to defend a threatened Emperor from foreigners was not fundamentally different from rallying to defend an unruly Emperor from the Bakufu itself, the Tokugawa régime was not favorably disposed in respect of this proposal and it came to naught. The Bakufu itself was considering a different railway scheme that would have enabled it to rush troops from its seat of power in Edō to Kyōto if things got out of hand.

In late 1866, the American Legation was confidentially advised that the Shōgunate had resolved to build a railway from Kyōto to Edō, along an inland route. This would have run through tea growing districts, then a major source of Japanese foreign trade revenue, and also would have avoided coastal areas prone to foreign bombardment (as had occurred at Shimonoseki) and colonial occupation of the line. The Tokugawa scheme reported in a later official dispatch to the US State Department also called for a northern extension to the silk districts, probably those in the Takasaki/Maebashi vicinity, which also would have a secondary purpose of linking close-by Nikko, where the ancestral tombs of notable Tokugawa Shōguns were found and rich copper deposits could be exploited, with Edō. This would have formed a great central trunk line through Japan, connecting Edō and the north with the populous Kansai plain on which Kyōto and Ōsaka are located, and thus have joined the two capitals of the Shōgun and the Emperor. According to US diplomatic correspondence, the Tokugawa railway proposal had progressed at least to the point where a preliminary “though hasty” route survey had been made, and young Tokugawa functionaries had been sent to Europe to study railway building and earn engineering degrees, with more expected to do the same in the United States.

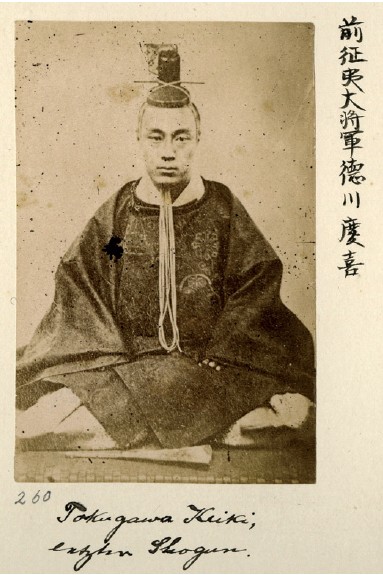

Japan’s last Shōgun was Tokugawa Yoshinobu, shown here in traditional court attire. Also known by the sobriquet Keiki, the last Shōgun was not initially considered to be among the leading candidates for the position. Among the last major foreign policy actions of his régime was the issuing of Japan’s first railway grant to Anton L. C. Portman, the American Legation’s Chargé d’Affaires, only days before the start of the Boshin War that would sweep the 250 year old dynasty of his ancestors from power.

Unfortunately for the Tokugawa Shōgunate at this time, both the financial and political situations were highly uncertain, and the Tokugawa railway proposal was postponed indefinitely. Foreign ministers at the head of their respective legations did the best they could to assess the likely outcome of the political unrest. The French minister, Léon Roches arrived in Japan in April 1864 and quickly set about ingratiating himself with the Bakufu, with notable success. In eminently reasonable Cartesian terms, Roches concluded that as the Bakufu was the legitimately recognized government of Japan as a matter of international law, he should treat with the Bakufu and not with the Imperial Court in Kyōto. Thereafter the French favored the Tokugawa régime. Roches became a favorite of the Bakufu, which had started slowly to modernize and adopt Western technology, and won for French interests the awarding of contracts to build a naval base, docks, repair facility, and arsenal for a planned modern navy at Yokosaka (south of Yokohama on the Miura peninsula), to build silk textile factories, to furnish technical advisors to assist in modernizing the Army, and to build and equip a modern mint. Roches submitted his own railway proposal, again made in 1866, for a railway from Edō to Kyōto with French technical and financial assistance, which would have been as useful to the Bakufu in maintaining primacy in Kyōto as a railway from Ōsaka to Kyōto would have been for the Chōshū-Satsuma Alliance, but the Bakufu was determined to build it solely using Japanese funding and labor. By the end of 1867 the Bakufu had taken the steps of proposing a program that would have restructured the existing government and financed national development through taxes on the daimyō for projects such as military, educational, telegraphic, navigational, and railway development. The daimyō were not inclined to agree to such a drastic tax on their income, and the proposal was abandoned.

The newly installed head of the British legation, Sir Harry Smith Parkes, landed in Nagasaki in 1865 and met Glover. Perhaps because Glover had introduced him to high ranking Chōshū-Satsuma Alliance members (who Glover had befriended) before Parkes departed for Yokohama, and thereby afforded him the chance to form an opinion as to their competency, military might, morale, and motivation, Parkes took an altogether different view of the events of the day, and was inclined to bide his time, believing that the Chōshū-Satsuma Alliance and gathering backers of the Emperor had a better chance of success than might otherwise have been thought. Before not too long a time, Sir Harry had become more and more sympathetically disposed to the cause of restoring power to the Emperor.

Parkes was, to say the least, a colorful, strong, and forceful character, at a time when British diplomats in the Far East (and elsewhere) were not in the least afraid to be forceful. He was completely his own master and had learned quite well how to maintain a resolute character in the face of adversity, having been orphaned in the year 1833 at age five and sent to live with an uncle, who died in 1837, obliging him to set sail for China in 1841, to live with a cousin who lived in Macao. He had served in the British diplomatic corps in a lower rank in China since 1842 at age 14. As such, he had participated in the diplomatic maneuverings necessitated by the Opium Wars and had been hardened and tempered by his own experiences forged in adversity and cast from the crucible of China. Parkes was appointed Consul of Canton in 1856 at age 28 and stood down the Chinese Commissioner Yeh over his seizing the British lorcha Arrow, which incident sparked the so-called “Arrow War.” Hostilities between Britain and China flared up again in 1860, and Parkes was sent to Tungchow, near Beijing, as part of the British diplomatic team at the conclusion to negotiate settlement terms. On arrival, Parkes found his diplomatic immunity disregarded by the Chinese and himself taken captive and made prisoner for several weeks. (Parkes’ imprisonment and mis-treatment is said to have been part of the justification for the British sacking and burning the Summer Palace in Beijing in punishment for what they viewed as a flagrant disregard of the principle of diplomatic immunity.) By the time Parkes was appointed the United Kingdom’s Minister to Japan in 1865, he was self-assured, worldly wise, and could be quite obdurate. And while undoubtedly he could be quite tactful and charming when it served his purposes, likewise he could bully, intimidate, and be a martinet when it behooved him. The story is told that despite the fact that he was by one year Roches’ junior in terms of diplomatic standing, he succeeded on one occasion in forcing his way in to a private meeting between Roches and the Shōgun himself on grounds of equal treatment for Her Britannic Majesty’s Minister. Another example of his forcefulness is found in the December 29, 1873 issue of the New York Times, where it was reported that at one State Dinner in the presence of the Emperor, Parkes, who then held senior status among Tōkyō Ministers, rose to give a toast to the Emperor “accompanied by a neat little speech,” but when it came time for the American Minister’s toast, Parkes literally shushed him at mid-point of the first sentence and told him to sit down; shouting him down with the abrupt words “No more.” Parkes’ objection? The American Minister’s grave offense lay in the formula used in his toast, which had wished “Prosperity, happiness and progress to the Sovereign and People of Japan” and, according to Sir Harry, mentioning the People of Japan in the same breath as the Emperor was “superfluous” and out of order as unduly political. As John Black, the man responsible for introduction of modern journalism to Japan and editor of one of its first English language newspapers put it, “The Japanese officials who were brought into communications with them [foreign ministers], complained sadly of the brusque manner in which they were frequently treated by the plain-speaking strangers. Especially was this the case with regard to Sir Harry Parkes, on whose absolute outbursts of wrath and excited action, they are never tired of dilating.”

Japanese railways adopted English-style car-floor level platforms from their earliest days, a wise choice given the density passenger traffic that would soon be the main source of revenue. This view shows a typical large station at an unidentified important regional town, circa 1900. Compare the neatness of this platform with the rudimentary platform depicted on page 103.

By 1867, the US Minister was Robert Van Valkenburgh, a New Yorker who had served in the US Congress, and who along with Roches, also tended to sympathize with the Bakufu. Shortly after Roches’ railway proposal, and a competing proposal by one Carle L. Westwood, an American named Anton L. C. Portman met with Bakufu officials and made yet a third proposal to build a line from Edō to Yokohama in the form of a concession (i.e. the line would not have been built for the Japanese Government, but was to have been financed with American capital and to have remained American-owned under the control of its American owners). Portman, a naturalized American who had been born in Holland, had been attached to the Perry expedition as a mere clerk, but when the attempts to communicate with the Japanese using Chinese proved to be such a shambles that the Japanese refused to negotiate in that language, Dutch was hurriedly substituted,4 and Portman, who spoke Dutch, proved invaluable and was pressed into service. (Congress later resolved to increase his pay to three times the original sum in view of his contribution to the success of the Perry Expedition.) By 1867, he had risen to become the Secretary, what today would be the Deputy Chief of Mission; second in command of the US Legation in Japan. When he learned of the Tokugawa project to build a railway from Edō to Kyōto in 1866 he saw an opportunity. During the course of 1867, he devoted increasing portions of his time to obtaining for American interests the right to participate in the first railway building. He undoubtedly pointed out that Americans had an enviable record of railway building and were well along in the process of building the World’s first transcontinental railroad and likely reminded the Bakufu that the French and the English had been awarded contracts for building all the major public works projects then underway and that it was unfair to exclude Americans from such undertakings. He inquired of his counterparts in the Bakufu why there was no provision in the new Tokugawa railway project for a branch to Yokohama, Japan’s most important port, less than two dozen miles away from Edō. His counterparts at the Ministry for Foreign Affairs replied that due to the increasing anti-foreign sonno jōi political sentiment then prevailing in Japan, it was felt that allowing anyone other than Japanese to build the railway would have aroused contrary public opinion to an unmanageable level. Portman then skillfully proposed to build only a branch railway of the Tokugawa grand trunk line: a section between Edō and Yokohama, astutely pointing out that the Yokohama line did not even have to be physically connected to the Tokugawa Grand Trunk Line, and that the building by Americans of a short line of railway could only serve to underscore the importance and nationalistic character of the achievement of the projected Grand Trunk Line. He succeeded where others had failed in concluding negotiations with the Bakufu for a railway concession in part due to timing. By late 1867, relations with anti-Tokugawa daimyō had turned so sour that there was little political disadvantage in risking arousing them on smaller subsidiary issues. The Bakufu felt that while, given the impending struggle it could foresee, it could ill-afford to budget domestic funds for its projected grand trunk line, there was little reason why foreign money couldn’t be put to use on the smaller Yokohama line, which at least would be helpful in the logistical support and supplying of troops and material likely to be needed to be sent from Edō. Accordingly, Portman was granted a concession to build the line from Edō to Yokohama by the Foreign Minister; an official then honored with the title of Ogasawara Iki no Kami, on January 16th, 1868 (December 23rd of the preceding year by the Japanese lunar calendar) in what was to be one of the last major foreign policy actions of the Shōgunate. In a later diplomatic dispatch, it was said that the two men, who had grown over the course of their years of interaction to be longstanding friends, had an understanding to keep the existence of the grant confidential for as long as feasible, so as not to cause further problems for the Bakufu in difficult times or to arouse the sensibilities of the British or French Ministers.

Léon Roches, Minister Plenipotential and Envoy Extraordinary of Napoléon III, Emperor of the French, to Japan, 1864–1868.

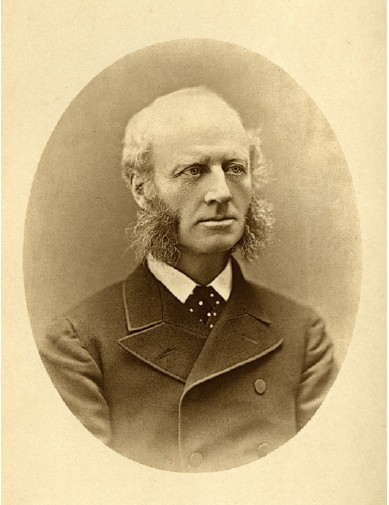

Sir Harry Parkes, Her Brittanic Majesty’s Minister Plenipotential and Envoy Extraordinary to Japan from 1865 to 1882, in a photograph taken around 1879.

The grant itself was fairly succinct; a one-sentence paragraph in the original translation, the only notable aspect of which allowed Portman to designate persons to undertake actual construction and financing. As a government official, as it was later quite correctly observed, Portman was by US law “strictly debarred from seeking profit” on the grant, and it is clear from the correspondence surrounding the grant that Portman intended to seek financial and technical backers from America rather than attempt to construct the line himself. Simple though the grant was, it was accompanied by a comprehensive, though broad, statement of 14 conditions,5 which served as the “rules and regulations” governing the grant: The deadline for starting construction was five years from the date of the grant, and once started, the deadline for completion was three years from the start date. The line was forbidden to interfere with the Tokaidō, the main road between Edō and Kyōto, and was required for safety to be fenced. If it ran through rice fields, it would not be permitted to interfere with drainage or irrigation. Rates were capped at a maximum of 25% above prevailing British and American rates, with Japanese Government officials granted a 50% discount in travel rates. [Shipment of troops, materiel, freight, or mail by the Japanese Government was not addressed.] The government reserved the right to regulate and enforce safety and engineering inspection oversight and undertook to facilitate surveying and construction contract letting with local contractors, to insure faithful and punctual performance of such contracts, and to undertake and complete the necessary land acquisition for the line within 6 months of receiving the final survey. Annual ground rents for the land acquired were set and a rudimentary payment schedule was established. The government required a full accounting of the cost of the line upon completion, annual reporting of receipts and expenditures thereafter, and reserved the right to purchase the railway at any time at a premium of 50% over its “cost price.” Finally, the government guaranteed that Japanese nationals would be free to travel on the line and to buy and own shares of stock in the enterprise free of taxation, and that the government would not interfere with actual management and operation.

Robert Van Valkenburgh, the American Minister Resident to Japan, 1866–1869. As mere Minister Resident, the senior American diplomat in Japan was inferior in diplomatic rank to his British and French counterparts.

This rare view shows US Minister Resident Van Valkenburgh standing at the left of a group of Tokugawa Bakufu dignitaries. Among them is Katsu Kaishi (seated, far left), captain of the first Japanese steamship that traveled to the United States in 1860, bringing with it the first Japanese mission to the United States. The Tokugawa military reformer and modernizer Ōzeki Masuhiro is identified as seated at far right. But most intriguing is the Westerner standing in the center. It is highly likely that this is Anton L. C. Portman, who negotiated the first railway concession with the Bakufu. The photograph was taken on September 22, 1867—around the time Port-man was negotiating (or beginning to negotiate) that concession with the Shōgunate. Within roughly three months from the time this photograph was taken, the railway concession would be granted to him, while all the Bakufu officials pictured would be undergoing the process of being swept out of power. The photo was taken in the gardens of the Hama-Goten (lit. Beach Palace) of the Shōgun. It would be renamed the Hama-Rikyu after the Meiji restoration and was the location of the official reception and festivities that were held after the opening of the first railway.

In all, the conditions of the Portman grant demonstrates that it had been the subject of considered deliberation by the Bakufu and but for the excessively favorable rate caps, the simplistic formula of the purchase option, and the failure to foresee the advantage of requiring a favorable governmental rate for shipment of troops, materiel, freight, and mail, the document was on whole a very creditable first step into the railway building and regulation arena.

During the time Portman was conducting his negotiations, the domains of Chōshū and Satsuma had continued their remonstrances: an abortive punitive expedition against the so-called “Southern Daimyō” by the Shōgunate in 1866 had only served to underscore the military ineffectiveness of the Bakufu Government. The struggling and inept fourteenth Shōgun, Tokugawa Iemochi, died during the course of that expedition at age 20, and his death was used as a face-saving measure to cease pursuit until his successor Tokugawa Keiki (more commonly known in the West as Tokugawa Yoshinobu) was installed. Taking advantage of this, sensing the weakness of the Bakufu armies, seizing on the relative inexperience of the new Shōgun, and exploiting the potential for transitional difficulties they hoped would be a natural result in the Tokugawa administrative structure and in its chain of command, the Chōshū-Satsuma Alliance grew and the year 1867 saw it increasing pressure on the Shōgun to step aside. As the stage had been set for a final Chōshū-Satsuma/Tokugawa rivalry, so too was it set for a Anglo-French-American diplomatic rivalry for entrée and influence, with Roches whole-heartedly embracing the Tokugawa régime, the Americans trying to remain aloof, but preferring the known quantity of the Tokugawa régime to the unknown and avowedly anti-foreign sonno jōi hotheads of the so-called “Imperial Cause” which was the label preferred by the Chōshū-Satsuma Alliance, and the British becoming increasingly sympathetic to the Emperor (as an institution of real political power) and his Chōshū-Satsuma backers.

The year 1868 was the watershed. Armed conflict began only a few days after Ogasawara Iki no Kami had issued the railway grant to Portman and the spectre of civil war raised its head. The Bakufu moved to dislodge Chōshū-Satsuma troops surrounding the Emperor in Kyōto. At the four-day Battle of Fushimi (now a suburb of Kyōto) that began January 27th, the Chōshū-Satsuma Imperial forces eventually carried the day and the new Shōgun’s forces retreated to Ōsaka. After further adverse developments, the Shōgun withdrew to Edō on a steamer. Subsequent defeats and political machinations resulted in further setbacks for Yoshinobu. By that time, Yoshinobu had shown the first signs of potential for being an astute and skillful leader, but circumstances were such that he didn’t have enough time in which to develop those abilities. By July 1868 Yoshinobu, the fifteenth and final Tokugawa Shōgun, surrendered Edō castle and with it his capital city, and went into seclusion (as would a monk intent on renouncing all worldly connection) at a temple first in Ueno, then one of the northern neighborhoods of Edō, from which he removed later to a Tokugawa estate in Mito and finally to another in the vicinity of Shizuoka, both towns with strong Tokugawa associations. Meanwhile, not all his supporters surrendered and the battles continued. In August, a Tokugawa faction launched a ploy steeped in feudal intrigue: they announced that the recent declaration of the young prince Mutsuhito as Emperor had been the mistaken work of the misguided and proclaimed that the true Emperor was an Imperial Prince of the Blood, Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa, who was the chief abbot of the Kan’ei-ji temple in Edō, a very popular figure around whom the public could rally, known as the Miya-sama (High Prince). Conveniently, the Miya-sama happened to be the Shōgun’s paternal uncle. The realm now had two Emperors to whose cause partisans could rally at least in name; the Pretended Emperor was never taken seriously by those Japanese who were close enough to the situation to know the true state of affairs, and the extent to which the claim to the throne was actually asserted is at best doubtful, if indeed it ever could have been legitimized.

As the IJGR came to standardize its station designs by mid-Meiji, smaller stations were less grand affairs, as capital was scarce and was best used to buy costly imported equipment such as locomotives, turntables, pre-fabricated bridge sections, and rails. Accordingly, medium to small size stations were thoroughly utilitarian structures made of wood, plaster, and roofing tiles by local carpenters that varied little in materials and construction from a large house of the day. In this 1900 photograph, the only visible modern ‘luxury’ apparent is the water column (with its canvas tube) on the platform edge where the locomotive was expected to stop to replenish its water tanks. Compare this station with the intermediate station on the Ōsaka-Kōbe line on page 87 for a good illustration of how economization was affected after design responsibility had been reassigned from British yatoi and placed in native hands.

Both sides applied to the foreign diplomatic community for assistance. After meeting in concert, the foreign diplomatic community, then consisting in the main of the British, American, French, and Dutch Ministers, unanimously resolved to maintain a strict neutrality. Nevertheless, Roches, while officially neutral, personally remained unabashedly pro-Tokugawa. The US Minister Resident6 Van Valkenburgh reported to Washington, “I believe that M. Roches had imbued himself to a considerable extent with the Tycoon’s Government... He undoubtedly desired to sustain the Tycoon.” On the other hand, Parkes was officially neutral, although personally inclined to credit the Imperial Cause. Somewhere between the two extremes represented by Roches and Parkes stood the US Minister Resident Van Valkenburgh, who adopted a “wait it out” attitude, although he undoubtedly sympathized with the Tokugawa Shōgunate.

Van Valkenburgh was a former colonel and veteran of the US Civil War who had seen action at the Battle of Antietam and saw matters in terms of the “Southern” forces (i.e. the Chōshū-Satsuma Imperial Cause) versus the “Northern” (Tokugawa) forces, and tended to view the struggle as an allegory of the recently concluded American Civil War. He repeatedly dispatched rather too-rosy reports of “Northern” victories back to Washington, somehow managing to disregard the fact that the location of each battle giving rise to those reports was edging increasingly northward toward Edō with each such report. When Imperial forces entered Edō and took control of Edō Castle, the Miya-sama removed himself to Sendai in the north, as would any good pretender to the throne, giving rise to the so-called Northern Mikadoship. With him went remaining loyal Bakufu forces northward to Sendai, and the foreign community in Yokohama watched in rapt attention one day as the remaining ships of the fledgling navy loyal to the Tokugawa cause made a break out of their moorings in Edō and ran past Yokohama in plain view, chased by what ships the Imperial forces had available, but making good an escape to the Sendai Bay. Van Valkenburgh saw in this merely a tactical withdrawal by Tokugawa forces, who, he claimed, were waiting for winter, after the rice harvest had brought with it tax season, when the Tokugawa tax advantage would net it revenues far in excess of the revenues reasonably expected from the Chōshū-Satsuma domains, with which it could further finance its struggle. In fairness to Van Valkenburgh, there was in truth some merit to this scenario, and it might have proven prescient—but for the fact that the Tokugawa Shōgunate had, as a whole, simply lost the resolve to fight.

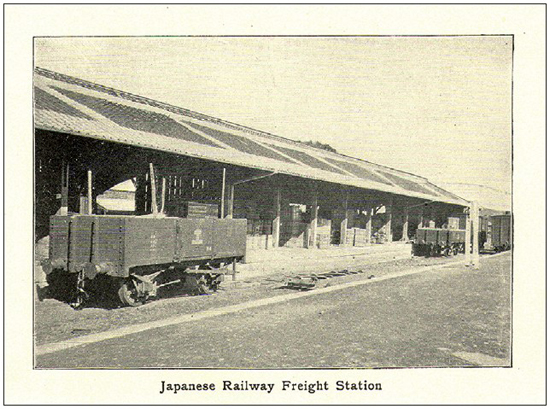

Early Japanese freight stations were even more Spartan structures than were passenger stations. Many, if not most, consisted of nothing more than an open-air punned earth platform canopied by a tiled roof. Due to long established coastal shipping habits and the location of most Japanese population centers along coastal areas, railway freight traffic was not initially as important as passenger traffic. Security at early freight stations often consisted of nothing more than a waist-high wooden fence. At this station, an IJGR 4-plank open wagon is seen in the foreground, but for its gauge, utterly comparable to any contemporary British wagon, with its buffers, loose coupling chain, underframe, and brake mechanism in the best British orthodoxy as of its build date. Note that only two of the four wheels on this particular wagon are braked; identifying it as an earlier build, although this particular photograph was taken circa 1899–1900.

The Bakufu had astutely sent two commissioners to America in the aftermath of the US Civil War having quite correctly perceived that with the war at an end, there might be a chance to buy surplus warships at bargain price without any construction lag. Over the next few years, they succeeded in negotiating the purchase of the Ironclad ram Stonewall for a price of $400,000.00, which had yet to be delivered when hostilities broke out in Japan. The Stonewall, as might be imagined from the name, was a state-of-the-art ironclad ram built in 1864 in France for the Confederate States Navy. After much delay caused by her embargo by the French Government as violating its declared neutrality, forced sale to Denmark (which subsequently refused delivery), and secret re-sale to the Confederate States Navy, the CSS Stonewall was finally commissioned in January, 1865, and had managed to steam only as far as Havana by war’s end, too late to have been any help to the Confederacy. The ship was delivered to the US Navy by Spanish authorities in Cuba in July 1865. With her state-of-the-art screw propellers, casemated guns, and heavy armor, she was considered fast and unsinkable. Her arrival in Confederate ports had been much dreaded by the US Navy in the final days of the war. With such a vessel, it was said, the Tokugawa forces could have single-handedly imposed a successful blockade of Ōsaka, and by extension, Kyōto as against any sortie the Chōshū-Satsuma forces could have arrayed to oppose her. Her arrival in port was anxiously awaited by both sides and when she dropped anchor at Yokohama on April 24, 1868, both factions made demands for her delivery as the legitimate government of Japan. Technically, the warship had been put under Japanese flag on its departure from the US and was accordingly a vessel of the Tokugawa Government upon payment of the last installment on arrival in port at Yokohama. But the fact of the pending payment gave Van Valkenburgh pause, and he opted to observe strict neutrality. On arrival at Yokohama, he ordered the Yankee crew to put the ironclad back under US flag and the watchful eye of the US naval squadron station there, and on behalf of his government he refused delivery to either side “until the restoration of peace.” The Bakufu generally abided by this arrangement and accepted matters as they were, but the Imperial partisans made repeated demands on Van Valkenburgh for delivery, the refusal of which did not ingratiate the American Minister with the Imperial faction. By the fourth or fifth demand in September of that year, upon the by-then customary refusal, the Imperial envoy took a different tack: He indicated that inasmuch as delivery of the ship was being refused, he was requesting a refund of the purchase price installments (only $300,000.00 had been paid) as “we are in want of money.” Van Valkenburgh again declined to release either the ram or a refund until the conclusion of a peace. But the incident stuck in his mind and illustrated to him in a very vivid manner just how cash-strapped and close to financial collapse the Chōshū-Satsuma Imperial alliance truly was. Curiously, neutrality notwithstanding, Van Valkenburgh was soon reporting in his official dispatches that the Chōshū-Satsuma Imperial alliance had succeeded in borrowing, as the legitimate government of Japan, a loan reputed to amount to between $500,000.00 and $600,000.00 Mexican from an unidentified British banking firm, which took as it’s collateral the customs revenue of Japan as security for the loan; security only a legitimately recognized government had a right to encumber. Clearly, British adherence to neutrality was not without some very conspicuous loopholes.

Between 1894 and 1896, the World Transportation Commission conducted a global tour to study and report on transportation progress. In Japan, their official photographer, William Henry Jackson, took this photograph of a relatively modest station, probably Takasaki.

Almost comically, Van Valkenburgh reasoned that the “Southern” forces would not be able to stand fighting in the cold north of Japan during winter, to the advantage of the Tokugawa forces who hailed from these regions, woefully underestimating the bushidō, or fighting spirit, that had been instilled in samurai over centuries, as reports of Southern “defeats” streamed in to Edō from points north that edged ever closer to Sendai during that fall despite the cold weather that was a supposed deterrent to the Southern forces. In September, in reply to reports that the Emperor himself would soon be coming to Edō, Van Valkenburgh wrote in his official dispatch to Washington, “... I doubt whether it will ever be seriously attempted.”

Parkes was having none of it. From about the time when the Shōgun had been obliged to flee Ōsaka, he had seen the inevitability of the Chōshū-Satsuma cause and the decay and lack of fighting resolve of the Tokugawa, and used his own presence in Ōsaka to which the representatives of the foreign diplomatic community had traveled for the opening of Hiogo as a new treaty port, as an opportunity to present new letters of credence, his diplomatic credentials, to the Emperor early in 1868, long before any of the other diplomats saw fit to do so. In this act, he was alone among the Ministers of the diplomatic community, and undoubtedly gained much good will with the Imperial Cause in so doing. Roches on the other hand remained so personally invested in the success of the Tokugawa Shōgunate that by February of 1868, when the Tokagawa defeats where becoming apparent to all but Van Valkenburgh, he sent a lengthy memorandum (by the standards of its day) to his colleagues attempting to justify continued maintenance of neutrality and tacit support for the Tokugawa status quo. Roches apparently felt such a stake in the outcome and a personal sense of the impending tragedy (as he perceived it) that Van Valkenburgh reported in a February 18 dispatch to the State Department that Roches had announced his intention to return to France, sua sponte, to explain his position directly to the Emperor Napoléon III, although one wonders if it was in fear of the possibility of a recall for having misjudged the situation. In the event, Roches did not immediately set sail, but remained in place until after his successor, Maxime Outrey, arrived in Yokohama on June 16th.

By the close of the year, the bitter cold of the north of Japan had in fact not prevented the Imperial Cause from amassing a victory, as Sendai gave up resistance, and the increasingly dwindling remnants of the Tokugawa military machine set sail on board the remaining Tokugawa vessels in Sendai Bay for points yet further north. The hold-out forces sailed for Yezo, northernmost of Japan’s four main islands, then a sparsely settled area of Japan not even recognized as a province proper, later to be re-named Hokkaidō. They landed at the port of Hakodate and declared the establishment of a Tokugawa Government-in-exile called the Republic of Yezo. But with all effective resistance now driven from the main island of Honshū, few, including Van Valkenburgh and Roches by this time, took the newly declared government at all seriously.

Meiji era freight operations are aptly shown in this photograph, probably taken from the opposing passenger platform of an unidentified station “en route to Kyōto” by a Western visitor who was probably traveling along the Tokaidō Line. Note the complete lack of ballast along the yard sidings and the interesting array of goods in transit, including a tree trunk loaded on one of the drays.

“Southern” troops pursued them, but there was an insufficient supply of Chōshū-Satsuma steamers to take them to Hokkaidō. Parkes very conveniently construed British neutrality to apply only to treaty ports and there was but one on Hokkaidō: Hakodate. He disingenuously declared he was powerless to stop the British merchant marine from transporting Imperial troops to other points along the Hokkaidō coast. The implication of Parkes’ interpretation was of course not lost on the British merchant marine, and charter steamers under British flag were soon discharging Imperial troops at a number of points of debarkation on Hokkaidō, but not at Hakodate proper. As soon as the newly arrived Prussian Minister Von Brandt learned of this, he adopted a similar position, on grounds that German merchant carriers were in no manner to be restrained from having the same profit opportunities as the British. In his dispatches to Washington, Van Valkenburgh was almost beside himself with righteous indignation over Parkes’ actions, which he characterized as “tantamount to a withdrawal of the neutrality enjoined upon British subjects” and, refused to turn a blind eye to American merchant marine carriers attempting to perform similar troop transport services.

Nevertheless, the handwriting was on the wall. In their New Year’s audience, the Italian and Dutch Ministers presented new letters of credence to the young Emperor. Roches was no longer Ministre Plénipotentiale de Sa Majesté l’Empéreur des Français and Maxime Outrey joined the Dutch Minister and newly-arrived Italian Minister in presenting his letters of credence at the same time. Van Valkenburgh, for his part, reported in his third dispatch of 1869 that at his first Imperial audience of the New Year, he told the young Emperor in part, “In the name of my Government I congratulate Your Majesty upon the present appearances of peace and prosperity and I trust the time will soon arrive when entire quiet will be re-established in all the parts of Your Majesty’s Empire...” (Emphasis added). Clearly Van Valkenburgh was admitting no less than circumstances dictated and perhaps was holding out hope for a working agreement between the Imperial forces and the remnants of the Shōgunate, and apparently on that occasion still did not present letters of credence. Van Valkenburgh remained hopeful of an Imperial-Tokugawa rapprochement almost to the bitter end, probably well after Roches had abandoned hope, but even he was soon to accept the reality of the situation and relent: on January 23, 1869 he informed the new Japanese Foreign Minister of his willingness to withdraw the US declaration of neutrality, but requested additional time on grounds that it would take time to arrange for all the foreign powers to do so simultaneously. A formal declaration to that effect, signed by all the foreign powers’ Ministers Resident, was proclaimed on February eighth. With the fall of the Tokugawa régime effectively accomplished both militarily and politically, the Imperial partisans had gained the legitimacy of international recognition. By shortly after New Year’s 1869 it was evident to all but the most myopic that Japan was presented with a political tabula rasa.