CHAPTER 4: 1873–1877

Kōbe to Kyōto

As the Kōbe–Ōsaka line was nearing completion, an artist for the Illustrated London News toured the line and sent back sketches of various civil engineering works along its length. Most of the bridges had been built of wood, with the exception of the larger ones. The Ashiya-gawa tunnel near Sumiyoshi is shown from both sides in the two vignettes that are next to bottom. Note that rails have yet to be laid across the deck of the long Mukogawa bridge.

December 1873 saw authorization to begin construction of the next segment of railway; a line starting at Kōbe, the new deep water treaty port 20 miles west of Ōsaka along the coast of the Ōsaka Bay, running to Ōsaka, the second largest city in the realm. The initial surveys for this line were started in July 1870, and as tasks were completed on the Shimbashi line and personnel could be spared, they were sent by steamer along the coast to the new port of Kōbe. By the close of 1871 the survey for the line had been staked out. As with the first line, matters had not gone well in the Kōbe–Ōsaka region, and Inoue thought things could be managed better close at hand and petitioned the government in early 1874 to move the main offices of the Railway Bureau to the Kōbe– Ōsaka area, in order to be closer to construction. There was more to be done in Kōbe than in Tōkyō. The management of daily operations of the Shimbashi line could have been handled more easily from a remote location than actual construction could have, so from a practical viewpoint his proposal made a considerable amount of sense. Unexpectedly, his petition was denied by Yamao Yozo, with whom friction had been developing, and this request set the two men on such a collision course that Inoue resigned in July of 1873. Itō eventually mended the rift, and Inoue resumed his office in January of 1874. As part of the rapprochement, Inoue’s relocation request was granted, and the seat of the Railway Bureau was thereupon temporarily moved to Kōbe.

There were some of the first real construction obstacles to be faced in the projected 20¼ mile segment from Kōbe to Ōsaka, first to be built of the Kōbe–Kyōto route. The first serious bridging (necessitating use of the first iron bridges) and the first “tunneling” of a sort was encountered on this section. Being volcanic in nature, the principal geographic feature of the Japanese islands is a central mountainous range, to quite high elevations at some points, with plains along the coasts. It is said that only some 17% of Japan is non-mountainous. The mountains of Honshū, the main island on which Tōkyō, Ōsaka, and Kyōto are located, run almost the entire length of the island in a backbone formation along its longitudinal centerline. A corollary to this is the fact that many rivers in Japan transform themselves from small streams of modest width in dry months to raging torrents hundreds of feet wide during the winter melt-off and rainy months, as the steep courses of the rivers descending from high altitude mountain slopes give rise to swiftly flowing water. Consequently, rivers often overflowed what were their normal channels the rest of the year, resulting in frequent devastating floods. Because of this, bridging had to be undertaken with greater caution and much sturdier bridges had to be constructed than ever would have been the case with the tamer rivers found in Great Britain or the eastern seaboard of the United States. Streams that could have been crossed easily by a small span of 50 feet during most of the year had to be built many times longer to allow for the wide raging torrents. Additionally, due to its underlying geology and volcanic nature, Japan was highly earthquake-prone, and bridges had to be engineered with this in mind at a time when seismology was only in its infancy. As a result, brick and mortar bridges with long arch spans were generally considered too brittle and were only rarely used. Wrought iron (and later steel) bridges came to be preferred as they were sturdier than wood and more flexible than brick and mortar. The initial care that went into the design of the bridges along this and future railway lines would soon return dividends to the country. Indeed, it would soon be seen that the bridges the railways had built would often be the only bridges to withstand severe flooding, the native wooden bridges being washed out, leaving the railway bridges the only ones standing for miles around. The general populace of the time often pressed them into service for relief efforts and general road traffic until the floodwaters had calmed enough to use ferries and rebuilding roadway bridges could be commenced.

The Shimbashi line zero milepost surveyor, John Diak, was made the Resident Engineer of the new line. As it basically followed the coastline, mountains were not a problem, but several rivers were, and these were the chief obstacles. To add interest to the undertaking, it was not uncommon to find that rivers of the day were above the level of the surrounding countryside; fantastic as this may seem. As the mountain-sourced currents were strong, the streams had a higher capacity to carry large amounts of silt; accordingly as they reached flatter land and their currents slowed the suspended silt settled, and silting occurred at a quicker rate. As the rivers silted, they became much more prone to flooding due to their increasingly shallow riverbeds. Because large scale dredging was beyond the technical capabilities of the Japanese prior to the arrival of Western dredging technology, they coped with the problem by expedient of building levees to contain the rivers. Because of this, the level of many rivers in Japan actually rose over time. The silting and levee-building cycle had continued for centuries, so that by the time the first of Morel’s engineers arrived in 1870, some of the river courses were as much as 40 feet above the level of the surrounding countryside. Three such rivers were encountered along the Kōbe–Ōsaka section, and it was seen as a better course to tunnel under them than to bridge over them.

After the final survey, acquisition of right of way, and staking of the line, usually the first works put underway are tunnels, bridging, and excessively long cuttings or embankments, as these are the works likely to take the longest time to complete, and so it was to be for the Kōbe–Ōsaka section, which was probably a bit unfortunate, as this came during the time of the inordinate disorganization seen on the Shimbashi line. Some of the disorganization evidently spilled over, for when Holtham arrived at Kōbe, he was disgusted to see that of the three tunnels; one had been built wide enough for a double line, while two had been built only wide enough for a single line, yet another example of the waste and poor planning that occurred in the starting days of railway building.

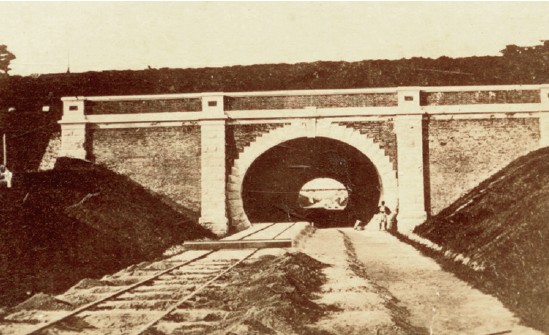

This photograph shows the Ashiya-gawa tunnel near Sumiyoshi that was built under the course of the Ashiya River, which had risen, over the course of centuries of silting and levee building in a chronic cycle, to the level shown. The photograph dates to the period before the Kōbe–Ōsaka line was opened in May, 1874, as very clearly the line is in the midst of final grading and ballasting in this image, giving an excellent view of the line’s earthen floor, sub-base of coarse ballast, and finer top layer with a ballast spreader left laying across the line at the point where finishing efforts had been concluded. Note the gentleman standing at the tunnel mouth at the right, giving an idea of the scale of the structure: is this the same samurai in his Mitsu-aoi crested haori with his back to the camera who appears in the Ōsaka station photograph on page 91? Of the three tunnels in this stretch of line, this tunnel was the only one built to accommodate double tracks. A bridge is barely visible in the distance, but can be seen, viewed from the other side, in the Illustrated London News drawing shown on page 86.

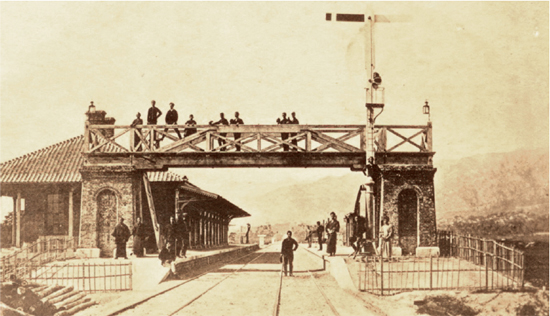

The start of Japan’s second railway line is shown in this view, taken from the Kōbe station yards, looking along the line as it departs roughly northeasterly on its run to Ōsaka. Adequate ground has been reserved for future expansion of the yards, although apparently not all the rubble remaining from construction has been cleared. The bridge seen at mid-ground is the “Aioibashi,” which is the vantage point where three photos shown in later pages were taken. The view probably dates from the first years of operation, around 1875.

The line started at a completely new wrought iron pier which the Railway Bureau built at Kōbe as part of the line, extending out into the water some 450 feet and 40 feet wide, enough breadth to accommodate three rail lines, and equipped with a traverser at the end (a type of sliding deck with track on it, onto which cars could be rolled, slid sideways to another track, and then rolled off). This configuration permitted two ships on either side of the dock to be loaded or off-loaded directly to or from railway cars without interruption. Thus in the case of off-loading, empty cars were pushed onto the dock from land and as they became loaded were rolled out to the end of the pier, shifted to the center track, and pushed or pulled back onto land without having to interfere with the loading or off-loading operations taking place simultaneously on either side. (The freight cars of the day were small, squarish British-style 4-wheel cars of an 8-foot wheelbase that could easily be pulled by a good draught horse, or pushed by three or four men.) For many years this was one of the best docks at Kōbe, and it was strictly reserved for government ships or ships on official business only. Not even Yokohama, the premier port of the realm, could claim to have as modern a port facility at the time. Its first landing pier of comparable stature there was not constructed until 1889.

A detail-laden view of one of the original Kōbe–Ōsaka line intermediate stations, Kanzaki, known today as Amagasaki. The station took its name from the nearby Kanzaki river and initially consisted of nothing more than a passing siding configuration, but was substantially provided with a neat brick station building and a charming footbridge built to rather high standards with ornate brick piers on an ogee-carved stone foundation at a time when funds were short and a simple all-wood structure would have been more economical; evidence of the British desire to build to a high standard ab initio. The view offers up a wealth of detail, from the water column in the foreground just under the finial-topped signal, to the very interesting signal itself, the two-tone tile pattern making a border around the rooflines, and the footbridge lanterns. One would like to think that some of 21 the individuals seen posing are the proud yatoi, engineering cadets from the Kōbudaigakkō, and local workmen who had a hand in building the line.

While the dock undoubtedly was the pride of the new terminal and went a great way towards expediting supply logistics, again it took an inordinate amount of time to complete the line, specifically the tunnels and bridging. The three tunnels combined only amounted to 250 yards. Advantage of the summer dry season was taken (when each of the rivers had dried to the size of an easily manageable stream) to divert the course of each river, make a large excavation or “cut” across the bed, build the section of tunnel lining with brick, encase it with generous amounts of cement, and cover the dirt back to form the riverbank before the rains started again. This “cut and cover” method was being pioneered right about that time to build the world’s first subway system in London, where streets where cut up, a tunnel dug below and bricked in, then the cut was covered back over with the spoils of excavation to the proper grade and paved. Meanwhile, in Japan, women and children were employed to remove the spoil of excavation, being paid on a ticket system. They were handed a ticket by a foreman for every two baskets of spoil deposited (as with the Shimbashi line, the local Japanese resisted excavating with wheel-barrows, and insisted on carrying away the spoil in two baskets, balanced over a shoulder pole, in time-honored Asian custom). At the end of the day, each worker was paid in accordance with the number of tickets he or she had accumulated. Also along this 20 mile stretch were no less than 208 bridges and culverts, the longest of which was over the Mukogawa, which was 1,190 feet long. It was on this section that the first wrought iron bridges were built.

The line was rather a straightforward run inland from the pier to a point beyond the foreign settlement, where it made a north-easterly curve toward Ōsaka, and then ran parallel along the coastline to its end in Ōsaka. There were initially four intermediate stations: Sannomiya, Sumiyoshi, Nishinomiya, and Kanzaki. In addition, near the Ōsaka station, a 1¾ mile branch to the Aji River [Aji-gawa] was laid down. The Ajigawa was the access point to the network of many canals and rivers used for transport in the area, so the Ajigawa branch railhead served as a point where goods from the outlying region brought in by canal boat could be transferred onto rail to be taken down to Kōbe where they could be loaded onto ocean-going vessels. It was intended to be nothing more than an expedient until a proper canal could be dug to the projected Ōsaka rail yards, where a docking basin would be excavated and facilities built. The branch was said to have operated at a loss. It was apparently a constant operational thorn in the side of the railway. It was closed on November 30, 1877 and pulled up after only 2½ years of operation—unquestionably the first abandoned railway line in Japan—by which point the canal, docking basin, and transshipment complex had been opened adjacent to the rail yard. This small branch and the Ōsaka Mint’s tramway both ended at Ōsaka station.

A station was put in place at Ōsaka that was a thoroughly English-inspired design. After four years of struggle the tunnels and bridges were completed. As these were the first railway tunnels in Japan the occasion called for a photographic commemoration, and one was duly made of the Ashiya-gawa tunnel, before trackage had been laid through it, showing the staff, crew, various of the laborers, and probably more than a few locals posed proudly at the mouth, along the cutting, atop the portals, and all along the riverbank above. While matters were progressing and the year turned to 1874, the Kōbushō was given the power to regulate rate changes in January, while luggage regulations were established in November. By spring of that year, the line was completed and was opened to Ōsaka for passenger traffic on May 11th. As Ōsaka was the largest center of commerce in Japan at that time, it was assumed from the start that freight service would be an integral part of operations of the new line. Parcel and freight traffic business started at the end of the year on December 1st. By year’s end, the bookkeepers reported that 505,733 passengers had been carried in seven months and twenty days of operation, while for the single month of December, 15,771 parcels had been carried along with 1,981 piculs (roughly 132 tons) of goods.

This rare view is believed to show the first line of railway ever abandoned in Japan and is one of a group of photographs from the UK, probably brought back by one of the yatoi who worked on the building of the Kōbe–Ōsaka line. Some of the photos are stamped “Miyazu, Kitaji, Naniwa” (Naniwa is an archaic name for Ōsaka) thus presumably Miyazu in the Kitaji neighborhood was the photographer. The photos all appear to date from around the time the Kōbe–Ōsaka line was opened. It is believed that this photograph shows the short lived Aji-gawa branch, which ran along the course of the Sonezaki river for part of its route prior to its terminus on the north bank of the Aji-gawa. The branch was cheaply built and never properly maintained as evidenced by the total lack of ballast seen here. It was envisioned as a temporary line and the tracks were taken up in 1877.

Again, English motive power and rolling stock were purchased for the line. Larger locomotives were ordered, due to the longer distances that expected when the line was completed to Kyōto—four 0-6-0 tender engines from Kitson and two 0-6-0T tanks from Manning-Wardle, which joined the two 0-4-2 tender locomotives previously ordered from Sharp Stewart. Around the same time orders were placed for four 2-4-0T tank engines from Stephenson similar to the ones used on the Shimbashi line and for additional Sharp 2-4-0Ts, which had proven themselves to be the best of the various original 2-4-0T types to be found on the nascent Government Railways. In 1871 and 1872 Brown & Marshall Britannia Works (perhaps also Saltley Works) had been called upon to provide passenger rolling stock for the line, and provided a range of compartment carriages much more typical of English designs of the period, with side-doors and three compartments rather than end doors and a central gangway. Rather surprisingly, they were built on an eight-foot wheelbase with an overall length of only 15 feet—tiny even by English standards of the day—possibly because such a small size would allow them to be moved about yards and sidings by a team of 3 or 4 men without need of locomotives. The surviving drawing of the First Class salon carriages ordered indicates that they were upholstered in blue Morocco leather, with silk lace trim and a wool fringe around the legs, sub-floored with patterned oil-cloth and carpeted over with Brussels carpet and were so tiny they seated only 12 passengers per car. Quaint 15 foot 4-wheel “birdcage roof passenger brake vans,” as they were called (in American terminology, baggage cars with cupolas) were likewise ordered. Goods stock appears to have been eight-foot wheel base standard stock with brakes on only two wheels, while the “brake vans” (cabooses) ordered were built on a 7’ 6” wheelbase, only 13’ 2½” long, and were essentially boxcars with a very truncated covered veranda at one end where the brakeman rode, exposed to the elements save for the roof. Probably in anticipation of the special shipments that the new mint at Ōsaka would create, a special “Bullion Van” had been ordered, which varied little in external appearance from the standard goods train brake van except for being fitted with sliding doors rather than a pair of hinged doors and for being 15’ 6” long, on a standard 8-foot wheelbase.

An Englishman who traveled to Ōsaka in the brief period during which it was the terminus left this account:

“Along with an American professor I had arrived in Kōbe by steamer through a rather tempestuous sea, sick, dirty, and miserable, amid a pallid crowd of woebegone Japanese fellow-passengers, if possible more sick and miserable than ourselves. The rain was pouring in torrents and a piercing wind chilled our very marrows as we landed. After a good hot bath, a sound sleep, and a very hearty mid-day breakfast, we walked round the settlement, which had been thoroughly washed down by the rain.... Close by is Hiogo, a characteristic old native town, where there is now the spacious terminus of a well-laid railway which runs to Ōsaka and [is projected beyond to] Kioto, and will yet, it is hoped, soon reach Tokio.... After drifting about the settlement in rather an aimless manner, we took tickets for Ōsaka, which was then the temporary terminus of the railway.

The railway crosses at a high level a spur of the range that encloses Kōbe and then darts down towards Ōsaka, straight as an arrow, by a series of alternating slopes and levels which had rather a striking appearance from the top of the incline. The traffic even then was very good, and seemed to bid fair for the ultimate success of railways in Japan....”

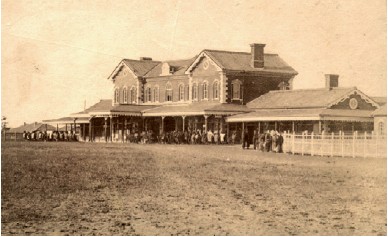

The original Ōsaka station from trackside on or shortly after its opening in 1874, giving a good view of the original configuration. The locomotive shed, water tank, and other subsidiary buildings are seen to the left. Notable is the fine trackwork and proper ballasting, again thanks to the high British engineering standards of the day, which included a proper pedestrian over-bridge at a time when traffic would not have justified its expense. Seen leaning against the platform canopy upright is an unidentified yatoi. A samurai proudly turns his back to the camera, probably for the purpose of exhibiting the ka-mon or family crest on the back of his haori; the three hollyhock leaf (Mitsu-Aoi) motif of which identifies him as possibly connected with the Tokugawa clan. The station itself would not have been out of place in the English Midlands.

This early photograph shows the façade of the original Ōsaka station. The site chosen for the station and yards was an expanse of sunken rice paddies then on the edge of Ōsaka that were filled in and leveled to grade. The local residents took to calling the area Umeda, 埋田, meaning “buried fields.” Later, the way Umeda was written was changed to the more euphemistic sounding and identically pronounced 梅田 (Plum-fields), as the original character combination could also be read as “burying fields.”

Another view of Ōsaka Station, early in its operation, probably the late 1870s, by which time a station bay track had been added on which the short trains stands. That train of three passenger cars and two brake vans is, judging by the orientation of the crewman seen leaning out the cab, departing the station bay on its way to Kōbe running bunker first, while another train stands at the main platform. Note the neat birdcage or cupola lookouts on the brake van roofs, to permit the guard to observe the train while underway for signs of axle boxes overheating or other mishaps. The locomotive is one of the Sharp Stewart specimens that would be classified as Class 120 in 1909.

Most of the shop and maintenance buildings were located in Kōbe, and were chiefly built of corrugated iron to save cost and time. In 1875, a wagon building works supplemental to the one also constructed at Shimbashi was completed and brought “on line” in Kōbe so that the rolling stock of passenger and freight cars could be built in Japan without having to import rolling stock from the UK, as had been done initially. Walter McKersie Smith was the first Works Superintendent. Steel parts such as wheels, axles, and buffing and draw gear were still imported from England, as Japan had no steel mills yet. But the Japanese have a long history of carpentry and skilled joinery and soon were turning out a very good product, even by the exacting standards of the British commentators of the day. Holtham, who was a frequent visitor to Kōbe at this time, recalls how this was the time when many of the old castles of the local daimyō had been ordered torn down by government decree. He goes on to recount that the Kōbe works “turned some seasoned timbers from pulled-down feudal castles into railway carriages.” In both the Kōbe and Shimbashi carshops, the underframe timbers of both passenger and goods cars were usually keyaki (Japanese Elm) while the floors, sides, and roof were made of hinoki (similar to red pine). Initially hinoki, kiou, or matsu (pine) was used for the crossties of the railway, but by 1907 kuri, similar to chestnut, was in almost universal use according to the Nippon Railway’s Superintendent of Way that year, S. Sugiura. On the Hokkaidō Tanko Tetsudō, the Chief Engineer Ōmura Takuichi reported that chestnut, oak, elm, spruce and yatitamo (similar to elm) were used by his line that same year. As creosote was not at that time manufactured in Japan, and as the cost of importing it was prohibitive, due to its highly flammable nature rendering it a shipping hazard, ties on the initial lines were not treated until domestic creosote production came into being. Progress in attaining self-sufficiency in car building was such that as early as 1885, a British diplomatic report mentions that Japan was producing her own rolling stock and largely was no longer importing it from England, only being dependent on foreign builders for locomotives. In fact, the shops at Shimbashi and Kōbe met not only the needs of the government railways, but built all the rolling stock for such soon-to-be formed early private lines as the Nippon Tetsudō, Ryomo Tetsudō, and Kōbu Tetsudō.

There was no noticeable break in construction operations at any time between the Kōbe–Ōsaka segment and the building of the Ōsaka–Kyōto segment: as soon as crews were not needed on the former section, they were sent to the latter. Interestingly, at about this time, in 1873, when there were only 40 miles of railway built in the entire realm, the Railway Bureau briefly considered adopting 1435mm/4’ 8½” as the standard gauge for all future railway building and re-gauging the existing lines, but the decision was made against re-gauging. This became the first of many occasions that followed in the future when the feasibility of re-gauging to 1435mm was considered, but would ultimately be rejected because of the prohibitive costs entailed. 1873 would henceforth always be recalled as a momentous lost chance in Japanese railway development. Inoue Masaru, writing in 1909, gainsaid the enormity of the task of converting the entirety of the national system to 4’ 8½” gauge in a gloss, making (without any support whatsoever) the glib conclusion that “an alteration of gauge can easily be effected whenever such a step be judged necessary in the public interest.” He should have known better. Francis Trevithick, the grandson of railway pioneer Richard Trevithick who with his brother Richard had joined the IJGR, did as early as 1894, when he voiced the conclusion that, “... it is too late... and for people to talk seriously about an alteration of gauge at the present time is foolish, and at the same time only showing their ignorance of the question.” Trevithick of course was right, but the mistake of adopting the narrow gauge came to be widely regretted. Nonetheless, more than a few futile man-hours would be devoted to studying the feasibility of re-gauging up to the point when Japan’s increasingly costly involvement in the coming world conflicts of the 1930s rendered such notions unthinkable from a fiscal standpoint.

The line to be built from Ōsaka to Kyōto was 27 miles in length, with five intermediate stations: Suita, Ibaraki, Takatsuki, Yamasaki, and Mukomachi; small brick structures for the most part, as brick was starting to become available from newly formed Japanese brickyards. There were five major river crossing (as compared to the size of the river crossings previously made): the Yushogawa, Kanasakigawa, Ibarakigawa, Odagawa, and Katsuragawa.

Holtham, who had been sent to do initial surveys of the line that was to run north from Lake Biwa to the Japan Sea at Tsuruga and eastwardly to Tōkyō was re-assigned to build a segment of the Ōsaka–Kyōto line on the completion of his initial survey. He was given the last construction segment, ending at Kyōto and containing the bridge over the Katsura River, from which we have a flavor of what construction was like.

While building that bridge, he complained that only one diving suit was available, which had to be shared with the crew building another bridge on the adjacent segment of line. Sinking the foundation wells, as he called them... structures sunk and lodged in the riverbed from which rose the uprights that supported the deck of the bridge... to form the foundation was a problem due to the character of the river bed which consisted of alternating harder and softer strata. The wells were floated out to position and were sunk to the river bottom easily enough, but as the riverbed material was being excavated from under the bottom lip to the desired depth for solidity, they would often be caught on a boulder or snag on a layer of the harder material that would impede their descent, sometimes causing them to lean to one side. Then as excavation was concentrated around the point of the problem, the underlying obstruction would give way, sometimes causing them to cant or list suddenly in a different direction. Keeping the wells to a true vertical as they were being sunk was the major problem. When obstructions were met, if it had been not borrowed and was not on-hand already, the diving suit would have to be sent for, and a Japanese diver would then suit up and be sent down to examine area around the wells and manually dislodge any boulders, stones, or obstructions found. This must have made for some excruciatingly slow going.

Work proceeded through small annoyances (heavy mosquito infestation) and large: one typical work day, Holtham was at his bridge when he looked over to the nearby thatched-roof storage canopy which had been built over his stack of timber balks to be used in bracing the bridge or as cross ties, to see the thatch going up in flame. He yelled to his head assistant Musha,1 work stopped immediately, and the entire crew scrambled to form a bucket brigade from the nearby river to save the supply. Time after that had to be spent bandaging those burnt putting out the fire, then back to the matter of building the bridge. Larger still were the annoyances caused by numerous jishin,2 sudden governmental re-organizations that were frequently taking place about that time and which, for a while, threatened him with premature termination of his employment contract, as they were often used as a technique to clean house of unaffordable, underperforming, or unwanted yatoi.

When the bridge was finally complete sometime in late summer of 1876, it was tested by bringing “two of the largest tender engines along with a train of heavy girders,” (two out of the only eight in the land, it might be added—these would have been taken either from the small Kitson 0-6-0 tender goods locomotives imported in 1873–1874 for freight service on the Kōbe–Kyōto line, two members of which were later rebuilt into 4-4-0 tender locomotives, or the diminutive Sharp Stewart 0-4-2 tender engines from the initial order) placing them both on the bridge, and marking any deflection against a pole that had been set with a witness mark previously. One smiles today at the thought that two of those tiny Kitson or Sharp-Stewart locomotives were the “heavyweights” of the day for bridge testing.

The Katsura was the last river barring the approach to Kyōto. Once all bridges were in place the entire length to Ōsaka, there was no obstruction to reaching the old Imperial capital. But things were not to be quite so easy. The plans for the Kyōto Station and other buildings had only been forthcoming from Kōbe headquarters in April 1876, so the buildings were in no state of readiness. Water towers, turntables and engine sheds were also lacking at Kyōto. When the plans for the station did finally arrive in April, they called for a granite-trimmed brick station with an entrance archway and small central clock tower almost certainly inspired by and notably similar to the clock tower at King’s Cross station in London. Holtham experienced more than the usual amount of difficulty finding suitable materials, specifically adequate amounts of granite stone of a uniform color for the clock tower and entrance. He was eventually forced to apply an expedient measure by saving the most uniform colored granite for the clock tower and central entrance arches, while using the inferior granite for the trim elsewhere on the building. For the time being, traffic was opened on the line on September 5, 1876 to a temporary station at Tōji (just south of the present day Umekoji Steam Museum).

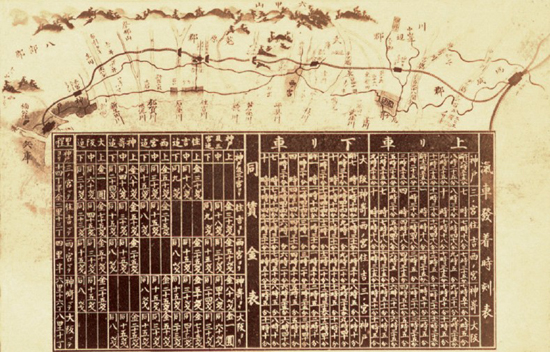

The first of these two photographs includes a hand-drawn map showing the route of the Kōbe–Ōsaka line, indicating the rivers under which it passed and the locations of intermediate stations. The second photo shows an early (if not the first) timetable for the line, with train departure times, and the fares for Upper 上, Middle 中, and Lower 下 Class passage, at a time before this had been changed to a more euphemistic “1st,” “2nd” and “3rd” Class.

About the time Holtham was focused on finishing the Kyōto station, arguing with quarry suppliers, and wondering how steam locomotives could be run into Kyōto without a means of replenishing the low water in their boilers, two momentous events took place: 1) the Railway Bureau ran out of money and 2) the unrest eventually leading to the Satsuma Rebellion reared its head in the south of Japan.

The Ministry of Finance and the Railway Bureau had been scraping together funds in a financial juggling act ever since the initial Oriental Bank loan proceeds had been consumed, and had struggled along, as least insofar as railway building is concerned by a variety of methods, not the least of which was the time-honored method of “cutting corners” of which Holtham’s shared diving suit is but one example. This was an era of frequent and recurrent jishin, Holtham’s dreaded government restructuring, and one could never be quite sure what to expect. By this point, the initial surveys for the line from Kyōto to Ōtsu, from Tsuruga south to Lake Biwa, and indeed beyond had been completed; a survey had started off from the projected Tsuruga line eastwards around Maibara on the shore of Lake Biwa, through the Sekigahara Gap (where Tokugawa Ieyasu had reunited Japan over two hundred and fifty years before) and forged on towards Gifu along the proposed initial route that had been envisioned toward Tōkyō. Because funding was close to exhaustion, an immediate stop work order went out for all activities except the completion of the Kyōto extension.

More troubling were the first rumblings of the Satsuma Rebellion, which were breaking out in Kyūshū, the southernmost of the four main Japanese islands. There had been a few minor rebellions since the restoration, but none serious. This was quite different, however. The Satsuma domains were among of the most powerful military powers in Japan, and their armed forces more seasoned than the fledgling Imperial Army. There are a number of causes of this rebellion; enough to account for why the Satsuma domains, which just ten years before had championed the Emperor’s authority, would now challenge it. Part of it was sonno jōi unhappiness with the sudden influx of foreign influence, and unhappiness over the government’s perceived inability to revise the extra-territoriality treaties and expel all foreigners. Part of it was sheer knee-jerk reactionary conservatism. Part of it also has to do with the government’s political, economic and social reforms that were deeply disadvantageous to the samurai class. For purposes of this narrative, one can perhaps be excused for grossly over-generalizing with the statement that the Meiji Government was systematically taking steps to eliminate the underpinnings of the samurai class’ socio-economic power.

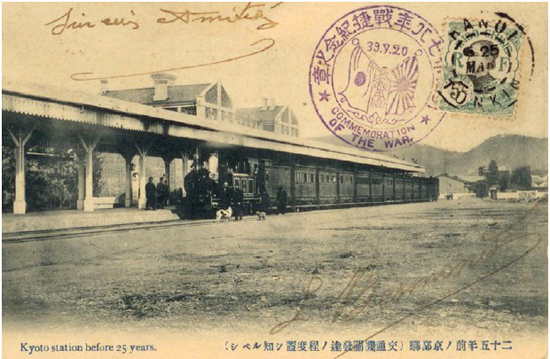

This turn-of-the-century postcard shows Kyōto station in its very earliest days of operation, when the railway terminated literally at the station’s end, and there were only a single platform track and parallel siding to be found there. A 13 car train consisting of the tiny 15 foot long passenger carriages and a brake-van (baggage car) at each end stands ready to depart for the run to Ōsaka and on to Kōbe. The locomotive bears number 38 on its chimney, indicating it is one of the Sharp 2-4-0T tank engines ordered for the line that would eventually become known as the ‘130’ class under the 1909 numbering scheme. Note the lined livery and prominent polished brass steam dome. The photo dates from the period after official inauguration on February 5, 1877 but before start of construction of the extension to Ōtsu in 1879, which began at the far end of the station.

In feudal Japan, the Samurai were a warrior caste, historically of the lower classes of Japanese aristocracy, who were used as the professional army by the higher-level aristocrats of Imperial rank. Their fundamental purpose as a class was to serve as professional soldiers. Strange as it may seem to modern minds, commonerspeasants, landed farmers, merchants, and artisans—did not serve any large military role in traditional Japan. Warcraft was mainly the province of the samurai, in exchange for which they received a guaranteed annual hereditary government stipend, measured in koku of rice (A koku equals about 5 bushels). By the end of the Tokugawa dynasty, the Bakufu had come to pay these stipends in the monetary equivalent of the market value of a koku. A fiefdom was said to be worth x thousands of koku in income, and daimyō status and prestige was gauged by these amounts.3 By the waning days of the Tokugawa Shogunate, with over 200 years having passed without serious armed conflict, most of the samurai had become a sedentary class of petty aristocracy who had little or no real military acumen, and as a class were largely unproductive. (However, this was not necessarily the case with the Shimazu clan of Satsuma and their supporters.) With the arrival of Western military might in the treaty ports, it became painfully obvious that relying on the samurai class in defense of the realm in the event of foreign invasion or intervention would not have been wise. One only had to look to the recent events in China or the British Navy’s bombardment of the Chōshū forts at Shimonoseki as an example of that futility. In 1873, the new government adopted the advice of their French military advisors for military reform and adopted the policy of universal conscription as the basis for the new army, which would henceforth also be composed of heimin, as the commoners of the day were called. This was a direct affront to the samurai as a class, and it was the handwriting on the wall. In 1869, all the various grade distinctions of samurai were streamlined into just two. In 1871 the government had taken the first tentative step to outlaw the carrying of swords by the samurai, who, as mentioned before, previously had been the only class allowed to wear swords, and who were told to cut off their top-knot hairstyles (another badge of class distinction) and to adopt Western dress. In that same year the commoners were informed that they no longer were required (as a matter of law as opposed to politesse) to kneel before samurai. The old restrictions against samurai farming, owning a trade or business, or making a living being anything other than a samurai were abolished. To a samurai, the clear message was: “You’re now no different than a well-dressed commoner.” Further moves by the central government around the same time were a decree that all castles of samurai be demolished (to deprive the samurai of their military power base) and the old provinces, over which a samurai daimyō ruled, were abolished; replaced by redrawn prefectures headed by a governor appointed by the central government, a Western political import, which of course deprived the samurai of their political base. Then there was the matter of taxation. The government was finding it increasingly difficult to maintain the cost of all the sudden modernization programs that it had set in place. Long-needed land tax reforms had just been made, but this benefited the farmer and peasant classes who were in sore need of relief. While, in the long run this proved to be a wise move, staving off mass discontent among those classes, it had the immediate effect of further reducing the inflow to state coffers. In the early 1870s, the annual stipends to samurai and subsidized domain debts consumed most of the government’s revenues, which was simply an unacceptable drain to state finances, given that the class had outlived its purpose. The government eventually decided it was time to take matters into hand and effect a settlement with the samurai in respect of the annual stipend payments, originally paid in exchange for the samurai’s defense obligations but which under the new system with a new army, were an utter waste. The government proposed a one time, final-settlement payment to the samurai, in the form of bonds to be given, following a formula. Naturally, many of the samurai were seething, particularly those in Satsuma, who were among the wealthiest domain holders, and stood to lose the most by being superannuated. In 1876 the government made acceptance of the bonds mandatory. Add to this a sense of betrayal by the very government many of them had worked to put in power and a festering resentment of the government’s inability to renegotiate the extraterritoriality treaties, and it is not difficult to see why matters were moving toward armed conflict.

The coming rebellion became visible late in 1876, but armed action didn’t occur until early in 1877 in Kyūshū; where the Satsuma forces besieged the local government garrisons (Satsuma province is in southern Kyūshū around the town of Kagoshima), at about the time the final works on the Ōsaka–Kyōto extension were nearing completion. At this point, the nation was in a high state of anxiety as to the outcome. The new heimin army was only a few years old and, other than a (successful) brief punitive expedition in 1874 to obliterate some villages in Taiwan in retaliation for their having captured and killed some stray Japanese fishermen, was utterly untested. It was being called upon to disassemble arguably the best-armed of the traditional fighting forces then known in the land, whose training and command structures were well-established. Moreover, the bulk of the naval officers corps were Satsuma men to the point that men from the Satsuma domains dominated the new Imperial Navy. No one was certain that the navy could be trusted to remain loyal. To add to the uncertainty, no one could be sure whether any of the foreign powers would maintain strict neutrality (as they did for America during the American Civil War) or would intervene on behalf of one of the disputants (as they did for China during the Chinese Taiping Rebellion). Around this time, foreign engineers assigned to the survey crews that were in the field surveying routes in remote villages started a routine practice of inquiring periodically of headquarters in Kōbe if the government was still in power and whether there was any imminent threat to foreigners that would require them to evacuate promptly back to the relative safety of the foreign settlement at Kōbe, as there was a strong anti-Western flavor to the Rebellion.4

The approaching completion of the Kyōto extension didn’t come at a good time for the government. The Emperor was expected to open the line. It was, after all, the line leading to the Imperial capital—and it would be a homecoming for him. To cancel the planned gala opening would have signaled a weakness on the part of the government, and might have encouraged more domains to ally themselves with their Satsuma peers. To go on would have meant taking the Emperor away from the government’s power base in Tōkyō and moving him to the Kōbe/Ōsaka/ Kyōto area at the northern edge of southern Japan, that much closer to rebel hands. Plus, there was the matter of the trip itself. Traveling overland via the Tokaidō would have taken over a month and would have required countless ceremonies and expense along the way. The route by steamship from Yokohama to Kōbe was about a 36 hour trip; clearly a preferable alternative, but the Emperor’s ship would have to be escorted by ships of the new navy, manned with large crew contingents of Satsuma men, of questionable loyalty.

It was a time when people speculated as to whether heimin could hold their own against samurai; whether the Emperor would make a show of it, or whether a face-saving reason for the line ‘not to be ready’ would be floated. At the new Kōbe car shops, work continued on the private Imperial car (described by contemporaries either as a “saloon car” or a “salon car” depending on whether the writer was British or American, respectively) that was being specially built for the occasion and word was periodically sent up to Kyōto from Kōbe headquarters to continue work to finish the station. One presumes that after some hard assessment of the loyalty of the Imperial Navy and the preparedness of the local army garrisons, to the satisfaction of the government and Imperial Household functionaries, the decision was made that the Emperor would indeed open the line. The Emperor’s steamship left Yokohama in the last week in January, escorted by vessels of war, put in at Toba, due to bad weather, and arrived at Kōbe on January 27th where the Emperor lodged overnight in the imposing new Western-style Post Office that had recently been completed; its offices being temporarily converted into and furnished out as State Apartments. The following day, all traffic was stopped on the line and a special train was run to Kyōto (presumably taking the Emperor and members of the Imperial Household, where they would reside at the Imperial Palace pending final preparations for the ceremony). The line was guarded by police its entire length and a detachment of troops was billeted at each station. The day following, service reverted to the station at Tōji and the Imperial Household Agency took full control of Kyōto station to prepare it for the opening ceremony, which had been set for February fifth.

Parkes was present as were a number of the Foreign Ministers representing the foreign diplomatic community. On behalf of that community, Parkes gave an address, which was notable in that it recognized the role railway building had played in gaining for Japan recognition of its concreted advancement among the nations of the world.5 Notable also for the event was the fact that the Empress attended, dressed for the first time in public in Western attire.

Holtham takes the story up on the morning of that ceremony:

“The [Kyōto station] offices were fitted up as withdrawing and reception rooms, and a sort of stage was built out in front of the station, carpeted and hung round with tapestry, with a gorgeous throne all proper. All the approaches were decorated, stands for spectators arranged, and curious devices set up, such as gigantic lanterns, dwarf Fujisans,6 ships, engines, etc., with Venetian masts, strings of lanterns and flags, and so on, and the same at both Ōsaka and Kōbe. The saloon carriage upon which the energies of the locomotive superintendent and the carriage department had been concentrated for six months past, was secretly run up to Kiyoto by night, as a thing ‘that mote not be prophaned of common eyes’ and No. 20 engine7 was painted and silvered up until she looked almost quite too beautiful, and the driver and stoker, even in their Sunday coats, were by no means congruous; so they were hidden in a grove of evergreen cunningly attached to the cab... I had to run down to Kōbe, where I secured the last hat there was in the place, so as to make a fitting appearance at the impending solemnity. We had been warned that nothing less than dress coats and white chokers, with the regulation chimney-pot hats, would qualify us to stand over against the foreign representatives upon the platforms at Kiyoto, Ōsaka, and Kōbe, subject to the gaze of thousands, while addresses were being presented and prayers recited. Of course some priests were mixed up in the matter, as indeed has been the case elsewhere than in Japan on occasion of railway festivities within my knowledge... The morning, though bitterly cold until the sun was well up, turned out bright and glorious, and we soon warmed up as the Imperial train started away from Kiyoto, amid great firing of guns and shouts from the populace. We engineers had a compartment next to the engine, with a friendly reporter and a pack of cards. At Ōsaka, a stoppage, and grave solemnities, firing of cannon, addresses, general enthusiasm, etc.: then en route for Kōbe, where more solemnities were perpetrated... Then there was a grand scramble for lunch, laid out in a room thirty feet by twenty, for five hundred people, one hungry engineer, who had been up since half past five that morning, getting a French roll and a bottle of beer for his share. The word soon passed that the Mikado had had enough of it... [apparently having been forewarned that a certain overly-zealous Kōbe foreign consul had prepared a written harangue in an attempt to corner the Emperor à la Parkes which Meiji naturally desired to avoid and circumvented by announcing an early departure]... and... at last... we started back, making the best of our way to Kiyoto without a stoppage. We arrived there safely, notwithstanding that we were turned through a siding at one station, instead of going by the direct [main] line, insomuch that after charging the points at a rate of thirty-five miles an hour, we were not quite sure if we were all right for a few seconds; and afterwards were desolated by the barely averted destruction of our Traffic Manager’s [Walter Page Smith’s] head against one of his own signal boxes at Ōsaka, which would have spoilt all the fun we derived from hearing the ambitious consul’s private address to the Mikado, read by our friend the reporter, who was the sole recipient of the document. However, we did the forty-seven miles in an hour and thirty-five minutes; say a rate of thirty-five miles an hour all through, which was quite fast enough for our narrow gauge; and his Imperial Majesty was good enough to cut short the final ceremony at Kiyoto, so that we were free at half-past four or thereabouts. The prettiest feature of the whole affair, to my mind, was the conduct of the country people all along the route. Wherever suitable ground could be found outside the fence, about on a level with the rails, spaces had been marked off to be occupied by the school children from the various villages of the district; some of these spaces extended alongside the line for half a mile together. Each school was in [the] charge of its teachers and the mayors and principal inhabitants of the villages, and as the Imperial train approached and passed the bands of eager girls or wondering-eyed boys bowed their heads and rose again,8 changing the bright field of expectant faces into an expanse of black polls, and then breaking out again with the flush of accomplished ceremony as the little ones clapped their hands and gazed after the vanishing train. The successive movement of the different corps of children had an effect like the passing of a summer cloud across a ripening cornfield. [Then back to Ōsaka later that evening for another celebratory banquet and, as there was no train back to Kyōto, taking the last train to Kōbe after the banquet to put up at Headquarters]... and somebody lost his boots on the way. It was for a time supposed that he had put them on the step [i.e., the running board of the passenger car] to be [picked up by his servant—undoubtedly booked in a lower class compartment—and] cleaned, [en route, so as to have clean boots] before he should get up in the morning, on entering the carriage; but at last there were found in the next compartment. And so finally we all got to bed and ended this eventful day.”

The incident of “charging the points at a rate of thirty-five miles an hours” is remarkable. Holtham is implicitly relating that the Meiji Emperor was a passenger aboard a train that came close to an accident. One of the points or switches at Ōsaka station had been improperly set. As a result, the train was routed through a siding that required reduced speed instead of along the mainline through the station—too suddenly for the driver to react. The train lurched violently at a speed far too excessive for the swerves of a sudden “S curve,” and Page Smith, who as traffic manager was responsible for train movements, immediately realized something was wrong and had on impulse very improvidently popped his head out of the train carriage window to see what was amiss, narrowly averting being hit by a passing signalman’s cabin as the train sped by.

Every time Queen Victoria traveled by train, all “points” or “switches” along the route were routinely padlocked in the proper direction as a security precaution and a decoy “pilot engine” ran before the actual Royal Train to prevent just such occurrences. In America, switches were routinely “spiked” (i.e. nailed in place with railroad spikes to prevent accidental or intentional misrouting) along routes of Presidential train travel. Here is evidence that such practices had yet to be introduced in Japan. It’s amazing that out of the entire British operating staff on hand, all railway men, not one had thought it necessary to adopt the routine practice of his native land and no one had seen fit to take a similar precaution. One presumes that more adequate practices were adopted for the benefit of the Japanese monarch from that day forward. That Holtham was more concerned with his Traffic Manager’s head than this serious security breach and operational failure evidences either embarrassment or the blithe manner in which Japanese railroading of the day was conducted, if not more. Almost certainly, Page Smith’s head would have found itself charged for negligent criminal conduct before an Ōsaka consular court instead of “... against a signal box,” and Parkes would have had a very regrettable diplomatic incident indeed on his hands given the stature of the personages involved had the train derailed with serious injury or loss of life.

Two days after the conclusion of opening festivities, the Emperor commenced a round of ceremonial visits in the region and shortly thereafter the first shots of the main engagements were fired in Kyūshū. In due course, the Emperor returned to Tōkyō unharmed and the nation was left to await the outcome of the rebellion. All was not well. It is difficult today to appreciate the precarious financial position of the Japanese Government in the period. In 1869, the government had so little funds at its disposal that it was obliged to seek an extension of time within which to make one of its indemnity installments from the Shimonoseki incident, which was not a large amount even by the standards of the time. In 1874, railway outlays for the Kyōto–Ōsaka line, small as that line was, amounted to just over 30% of the government’s investments among its development projects, but the need to finance the punitive expedition to Taiwan that same year severely taxed state coffers. The possibility of conflict with China over Taiwan resulted in the government lowering its railway expenditures to 7.1% of its total outlays in 1875. With the Satsuma Rebellion following in the van of the Taiwanese punitive expedition, the figure was pushed even lower. For the period 1876 to 1882 it amounted to only 4%. For the near future, railway building was to cease.

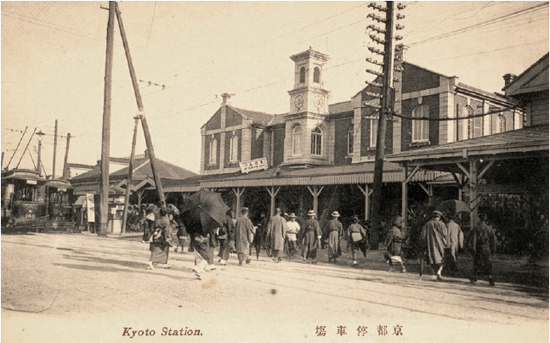

By the turn of the 20th Century, around when this photograph was taken, annex buildings had sprouted alongside the original Kyōto station building, and the electric trolleys of the Kyōto Municipal Railway were stopping in the forecourt. The sign on the veranda roof marks the entrance for Eastbound trains to Tōkyō.