The moving average is one of the most versatile and widely used of all technical indicators. Because of the way it is constructed and the fact that it can be so easily quantified and tested, it is the basis for many mechanical trend-following systems in use today.

Chart analysis is largely subjective and difficult to test. As a result, chart analysis does not lend itself that well to computerization. Moving average rules, by contrast, can easily be programmed into a computer, which then generates specific buy and sell signals. While two technicians may disagree as to whether a given price pattern is a triangle or a wedge, or whether the volume pattern favors the bull or bear side, moving average trend signals are precise and not open to debate.

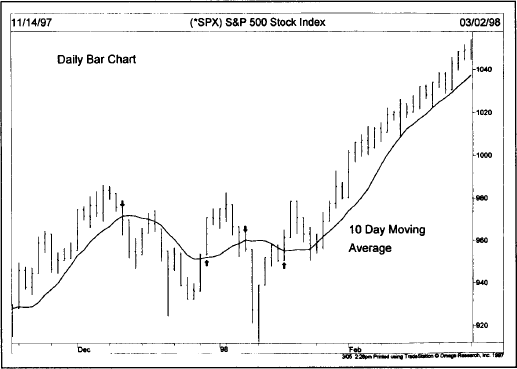

Let’s begin by defining what a moving average is. As the second word implies, it is an average of a certain body of data. For example, if a 10 day average of closing prices is desired, the prices for the last 10 days are added up and the total is divided by 10. The term moving is used because only the latest 10 days’ prices are used in the calculation. Therefore, the body of data to be averaged (the last 10 closing prices) moves forward with each new trading day. The most common way to calculate the moving average is to work from the total of the last 10 days’ closing prices. Each day the new close is added to the total and the close 11 days back is subtracted. The new total is then divided by the number of days (10). (See Figure 9.1a.)

The above example deals with a simple 10 day moving average of closing prices. There are, however, other types of moving averages that are not simple. There are also many questions as to the best way to employ the moving average. For example, how many days should be averaged? Should a short term or a long term average be used? Is there a best moving average for all markets or for each individual market? Is the closing price the best price to average? Would it be better to use more than one average?

Figure 9.1a A 10 day moving average applied to a daily bar chart of the S&P 500. Prices crossed the average line several times (see arrows) before finally turning higher. Prices stayed above the average during the subsequent rally. Which type of average works better—a simple, linearly weighted or exponentially smoothed? Are there times when moving averages work better than others?

There are many questions to be considered when using moving averages. We’ll address many of these questions in this chapter and show examples of some of the more common usages of the moving average.

The moving average is essentially a trend following device. Its purpose is to identify or signal that a new trend has begun or that an old trend has ended or reversed. Its purpose is to track the progress of the trend. It might be viewed as a curving trendline. It does not, however, predict market action in the same sense that standard chart analysis attempts to do. The moving average is a follower, not a leader. It never anticipates; it only reacts. The moving average follows a market and tells us that a trend has begun, but only after the fact.

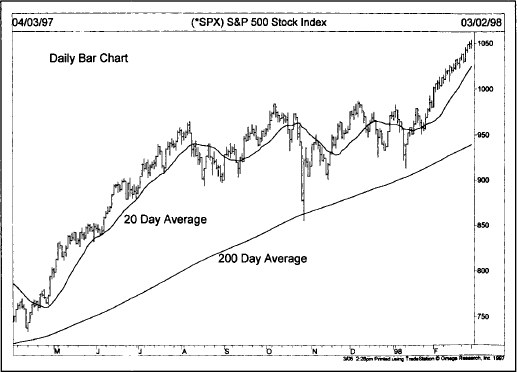

The moving average is a smoothing device. By averaging the price data, a smoother line is produced, making it much easier to view the underlying trend. By its very nature, however, the moving average line also lags the market action. A shorter moving average, such as a 20 day average, would hug the price action more closely than a 200 day average. The time lag is reduced with the shorter averages, but can never be completely eliminated. Shorter term averages are more sensitive to the price action, whereas longer range averages are less sensitive. In certain types of markets, it is more advantageous to use a shorter average and, at other times, a longer and less sensitive average proves more useful. (See Figure 9.1b.)

We have been using the closing price in all of our examples so far. However, while the closing price is considered to be the most important price of the trading day and the price most commonly used in moving average construction, the reader should be aware that some technicians prefer to use other prices. Some prefer to use a midpoint value, which is arrived at by dividing the day’s range by two.

Figure 9.1b A comparison of a 20 day and a 200 day moving average. During the sideways period from August to January, prices crossed the shorter average several times. However, they remained above the 200 day average throughout the entire period.

Others include the closing price in their calculation by adding the high, low, and closing prices together and dividing the sum by three. Still others prefer to construct price bands by averaging the high and low prices separately. The result is two separate moving average lines that act as a sort of volatility buffer or neutral zone. Despite these variations, the closing price is still the price most commonly used for moving average analysis and is the price that we’ll be focusing most of our attention on in this chapter.

The simple moving average, or the arithmetic mean, is the type used by most technical analysts. But there are some who question its usefulness on two points. The first criticism is that only the period covered by the average (the last 10 days, for example) is taken into account. The second criticism is that the simple moving average gives equal weight to each day’s price. In a 10 day average, the last day receives the same weight as the first day in the calculation. Each day’s price is assigned a 10% weighting. In a 5 day average, each day would have an equal 20% weighting. Some analysts believe that a heavier weighting should be given to the more recent price action.

In an attempt to correct the weighting problem, some analysts employ a linearly weighted moving average. In this calculation, the closing price of the 10th day (in the case of a 10 day average) would be multiplied by 10, the ninth day by nine, the eighth day by eight, and so on. The greater weight is therefore given to the more recent closings. The total is then divided by the sum of the multipliers (55 in the case of the 10 day average: 10 + 9 + 8 +…+ 1). However, the linearly weighted average still does not address the problem of including only the price action covered by the length of the average itself.

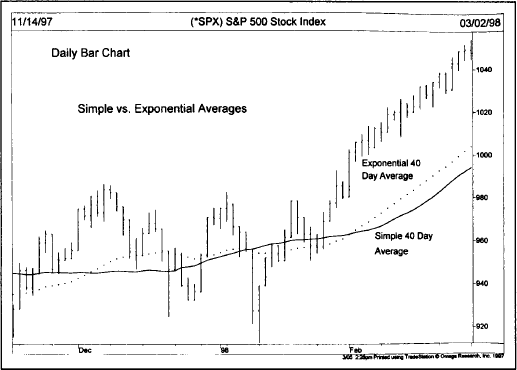

This type of average addresses both of the problems associated with the simple moving average. First, the exponentially smoothed average assigns a greater weight to the more recent data. Therefore, it is a weighted moving average. But while it assigns lesser importance to past price data, it does include in its calculation all of the data in the life of the instrument. In addition, the user is able to adjust the weighting to give greater or lesser weight to the most recent day’s price. This is done by assigning a percentage value to the last day’s price, which is added to a percentage of the previous day’s value. The sum of both percentage values adds up to 100. For example, the last day’s price could be assigned a value of 10% (.10), which is added to the previous day’s value of 90% (.90). That gives the last day 10% of the total weighting. That would be the equivalent of a 20 day average. By giving the last day’s price a smaller value of 5% (.05), lesser weight is given to the last day’s data and the average is less sensitive. That would be the equivalent of a 40 day moving average. (See Figure 9.2.)

Figure 9.2 The 40 day exponential moving average (dotted line) is more sensitive than the simple arithmetic 40 day moving average (solid line).

The computer makes this all very easy for you. You just have to choose the number of days you want in the moving average—10, 20, 40, etc. Then select the type of average you want—simple, weighted, or exponentially smoothed. You can also select as many averages as you want—one, two, or three.

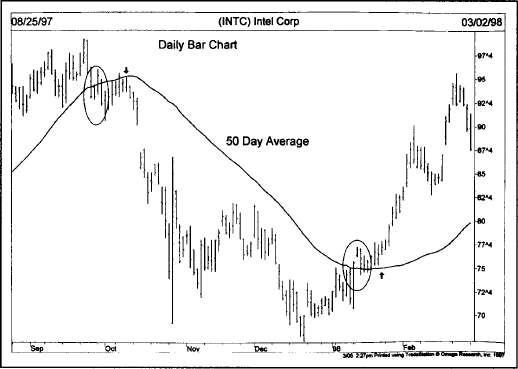

The simple moving average is the one most commonly used by technicians, and is the one that we’ll be concentrating on. Some traders use just one moving average to generate trend signals. The moving average is plotted on the bar chart in its appropriate trading day along with that day’s price action. When the closing price moves above the moving average, a buy signal is generated. A sell signal is given when prices move below the moving average. For added confirmation, some technicians also like to see the moving average line itself turn in the direction of the price crossing. (See Figure 9.3.)

If a very short term average is employed (a 5 or 10 day), the average tracks prices very closely and several crossings occur. This action can be either good or bad. The use of a very sensitive average produces more trades (with higher commission costs) and results in many false signals (whipsaws). If the average is too sensitive, some of the short term random price movement (or “noise”) activates bad trend signals.

Figure 9.3 Prices fell below the 50 day average during October (see left circle). The sell signal is stronger when the moving average also turns down (see left arrow). The buy signal during January was confirmed when the average itself turned higher.

While the shorter average generates more false signals, it has the advantage of giving trend signals earlier in the move. It stands to reason that the more sensitive the average, the earlier the signals will be. So there is a tradeoff at work here. The trick is to find the average that is sensitive enough to generate early signals, but insensitive enough to avoid most of the random “noise.” (See Figure 9.4.)

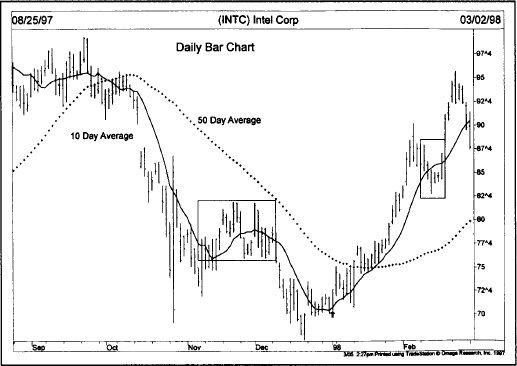

Figure 9.4 A shorter average gives earlier signals. The longer average is slower, but more reliable. The 10 day turned up first at the bottom. But it also gave a premature buy signal during November and an untimely sell signal during February (see boxes).

Let’s carry the above comparison a step further. While the longer average performs better while the trend remains in motion, it “gives back” a lot more when the trend reverses. The very insensitivity of the longer average (the fact that it trailed the trend from a greater distance), which kept it from getting tangled up in short term corrections during the trend, works against the trader when the trend actually reverses. Therefore, we’ll add another corollary here: The longer averages work better as long as the trend remains in force, but a shorter average is better when the trend is in the process of reversing.

It becomes clearer, therefore, that the use of one moving average alone has several disadvantages. It is usually more advantageous to employ two moving averages.

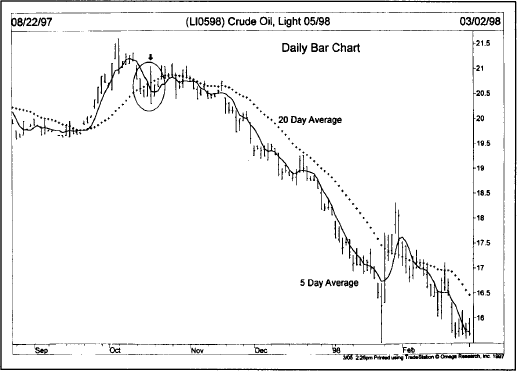

This technique is called the double crossover method. This means that a buy signal is produced when the shorter average crosses above the longer. For example, two popular combinations are the 5 and 20 day averages and the 10 and 50 day averages. In the former, a buy signal occurs when the 5 day average crosses above the 20, and a sell signal when the 5 day moves below the 20. In the latter example, the 10 day crossing above the 50 signals an uptrend, and a downtrend takes place with the 10 slipping under the 50. This technique of using two averages together lags the market a bit more than the use of a single average but produces fewer whipsaws. (See Figures 9.5 and 9.6.)

Figure 9.5 The double crossover method uses two moving averages. The 5 and 20 day combination is popular with futures traders. The 5 day fell below the 20 day during October (see circle) and caught the entire downtrend in crude oil prices.

That brings us to the triple crossover method. The most widely used triple crossover system is the popular 4-9-18-day moving average combination. The 4-9-18 method is used mainly in futures trading. This concept was first mentioned by R.C. Allen in his 1972 book, How to Build a Fortune in Commodities and again later in a 1974 work by the same author, How to Use the 4-Day, 9-Day and 18-Day Moving Averages to Earn Larger Profits from Commodities. The 4-9-18-day system is a variation on the 5, 10, and 20 day moving average numbers, which are widely used in commodity circles. Many commercial chart services publish the 4-9-18-day moving averages. (Many charting software packages use the 4-9-18-day combination as their default values when plotting three averages.)

Figure 9.6 Stock traders use 10 and 50 day moving averages. The 10 day fell below the 50 day in October (left circle), giving a timely sell signal. The bullish crossover in the other direction took place during January (lower circle).

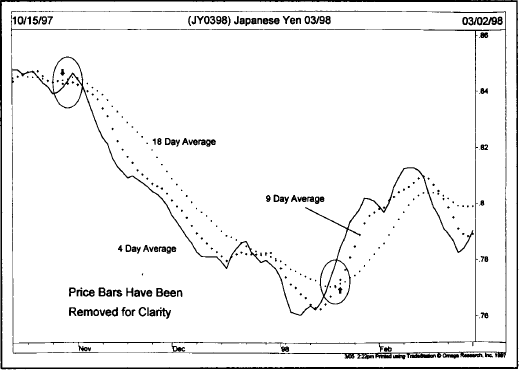

It’s already been explained that the shorter the moving average, the closer it follows the price trend. It stands to reason then that the shortest of the three averages—the 4 day—will follow the trend most closely, followed by the 9 day and then the 18. In an uptrend, therefore, the proper alignment would be for the 4 day average to be above the 9 day, which is above the 18 day average. In a downtrend, the order is reversed and the alignment is exactly the opposite. That is, the 4 day would be the lowest, followed by the 9 day and then the 18 day average. (See Figures 9.7a-b.)

A buying alert takes place in a downtrend when the 4 day crosses above both the 9 and the 18. A confirmed buy signal occurs when the 9 day then crosses above the 18. This places the 4 day over the 9 day which is over the 18 day. Some intermingling may occur during corrections or consolidations, but the general uptrend remains intact. Some traders may take profits during the intermingling process and some may use it as a buying opportunity. There is obviously a lot of room for flexibility here in applying the rules, depending on how aggressively one wants to trade.

Figure 9.7a Futures traders like the 9 and 18 day moving average combination. A sell signal was given in late October (first circle) when the 9 day fell below the 18. A buy signal was given in early 1998 when the 9 day crossed back above the 18 day.

When the uptrend reverses to the downside, the first thing that should take place is that the shortest (and most sensitive) average—the 4 day—dips below the 9 day and the 18 day. This is only a selling alert. Some traders, however, might use that initial crossing as reason enough to begin liquidating long positions. Then, if the next longer average—the 9 day—drops below the 18 day, a confirmed sell short signal is given.

Figure 9.7b The 4-9-18 day moving average combo is also popular with futures traders. At a bottom, the 4 day (solid line) turns up first and crosses the other two lines. Then the 9 day crosses over the 18 day (see circle), signaling a bottom.

The usefulness of a single moving average can be enhanced by surrounding it with envelopes. Percentage envelopes can be used to help determine when a market has gotten overextended in either direction. In other words, they tell us when prices have strayed too far from their moving average line. In order to do this, the envelopes are placed at fixed percentages above and below the average. Shorter term traders, for example, often use 3% envelopes around a simple 21 day moving average. When prices reach one of the envelopes (3% from the average), the short term trend is considered to be overextended. For long range analysis, some possible combinations include 5% envelopes around a 10 week average or a 10% envelope around a 40 week average. (See Figures 9.8a-b.)

Figure 9.8a 3% envelopes placed around a 21 day moving average of the Dow. Moves outside the envelopes suggest an overextended stock market.

Figure 9.8b For longer range analysis, 5% envelopes can be placed around a 10 week average. Moves outside the envelopes helped identify market extremes.

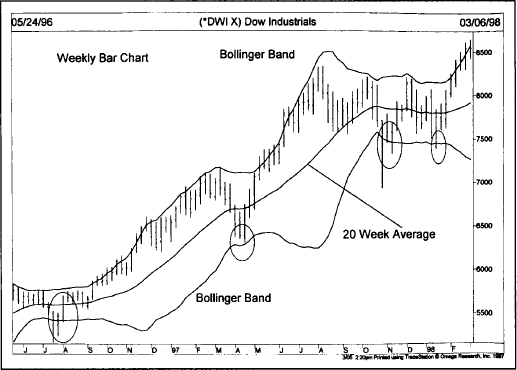

This technique was developed by John Bollinger. Two trading bands are placed around a moving average similar to the envelope technique. Except that Bollinger Bands are placed two standard deviations above and below the moving average, which is usually 20 days. Standard deviation is a statistical concept that describes how prices are dispersed around an average value. Using two standard deviations ensures that 95% of the price data will fall between the two trading bands. As a rule, prices are considered to be overextended on the upside (overbought) when they touch the upper band. They are considered overextended on the downside (oversold) when they touch the lower band. (See Figures 9.9a-b.)

Figure 9.9a Bollinger bands plotted around a 20 day moving average. During the sideways period from August to January, prices kept touching the outer bands. Once the uptrend resumed, prices traded between the upper band and 20 day average.

Figure 9.9b Bollinger bands work on weekly charts as well, by using a 20 week average as the middle line. Each touch of the lower band (see circles) signaled an important market bottom and a buying opportunity.

The simplest way to use Bollinger Bands is to use the upper and lower bands as price targets. In other words, if prices bounce off the lower band and cross above the 20 day average, the upper band becomes the upper price target. A crossing below the 20 day average would identify the lower band as the downside target. In a strong uptrend, prices will usually fluctuate between the upper band and the 20 day average. In that case, a crossing below the 20 day average warns of a trend reversal to the downside.

Bollinger Bands differ from envelopes in one major way. Whereas the envelopes stay a constant percentage width apart, Bollinger Bands expand and contract based on the last 20 days’ volatility. During a period of rising price volatility, the distance between the two bands will widen. Conversely, during a period of low market volatility, the distance between the two bands will contract. There is a tendency for the bands to alternate between expansion and contraction. When the bands are unusually far apart, that is often a sign that the current trend may be ending. When the distance between the two bands has narrowed too far, that is often a sign that a market may be about to initiate a new trend. Bollinger Bands can also be applied to weekly and monthly price charts by using 20 weeks and 20 months instead of 20 days. Bollinger Bands work best when combined with overbought/oversold oscillators that are explained in the next chapter. (See Appendix A for additional band techniques.)

The more statistically correct way to plot a moving average is to center it. That means to place it in the middle of the time period it covers. A 10 day average, for example, would be placed five days back. A 20 day average would be plotted 10 days back in time. Centering the average, however, has the major flaw of producing much later trend change signals. Therefore, moving averages are usually placed at the end of the time period covered instead of the middle. The centering technique is used almost exclusively by cyclic analysts to isolate underlying market cycles.

Many market analysts believe that time cycles play an important role in market movement. Because these time cycles are repetitive and can be measured, it is possible to determine the approximate times when market tops or bottoms will occur. Many different time cycles exist simultaneously, from a short term 5 day cycle to Kondratieff’s long 54 year cycle. We’ll delve more into this fascinating branch of technical analysis in Chapter 14.

The subject of cycles is introduced here only to make the point that there seems to be a relationship between the underlying cycles that affect a certain market and the correct moving averages to use. In other words, the moving averages can be adjusted to fit the dominant cycles in each market.

There appears to be a definite relationship between moving averages and cycles. For example, the monthly cycle is one of the best known cycles operating throughout the commodity markets. A month has 20-21 trading days. Cycles tend to be related to their next longer and shorter cycles harmonically, or by a factor of two. That means that the next longer cycle is double the length of a cycle and the next shorter cycle is half its length.

The monthly cycle, therefore, may explain the popularity of the 5, 10, 20, and 40 day moving averages. The 20 day cycle measures the monthly cycle. The 40 day average is double the 20 day. The 10 day average is half of 20 and the 5 day average is half again of 10.

Many of the more commonly used moving averages (including the 4, 9, and 18 day averages, which are derivatives of 5, 10, and 20) can be explained by cyclic influences and the harmonic relationships of neighboring cycles. Incidentally, the 4 week cycle may also help explain the success of the 4 week rule, covered later in the chapter, and its shorter counterpart—the 2 week rule.

We’ll cover the Fibonacci number series in the chapter on Elliott Wave Theory. However, I’d like to mention here that this mysterious series of numbers—such as 13, 21, 34, 55, and so on—seem to lend themselves quite well to moving average analysis. This is true not only of daily charts, but for weekly charts as well. The 21 day moving average is a Fibonacci number. On the weekly charts, the 13 week average has proven valuable in both stocks and commodities. We’ll postpone a more in depth discussion of these numbers until Chapter 13.

The reader should not overlook using this technique in longer range trend analysis. Longer range moving averages, such as 10 or 13 weeks, in conjunction with the 30 or 40 week average, have long been used in stock market analysis, but haven’t been given as much attention in the futures markets. The 10 and 40 week moving averages can be used to help track the primary trend on weekly charts for futures and stocks. (See Figure 9.10.)

Figure 9.10 Moving averages are valuable on weekly charts. The 40 week moving average should provide support during bull market corrections as it did here.

One of the great advantages of using moving averages, and one of the reasons they are so popular as trend-following systems, is that they embody some of the oldest maxims of successful trading. They trade in the direction of the trend. They let profits run and cut losses short. The moving average system forces the user to obey those rules by providing specific buy and sell signals based on those principles.

Because they are trend-following in nature, however, moving averages work best when markets are in a trending period. They perform very poorly when markets get choppy and trade sideways for a period of time. And that might be a third to a half of the time.

The fact that they do not work that well for significant periods of time, however, is one very compelling reason why it is dangerous to rely too heavily on the moving average technique. In certain trending markets, the moving average can’t be beat. Just switch the program to automatic. At other times, a nontrending method like the overbought–oversold oscillator is more appropriate. (In Chapter 15, we’ll show you an indicator called ADX that tells you when a market is trending and when it is not, and whether the market climate favors a trending moving average technique or a nontrending oscillator approach.)

One way to construct an oscillator is to compare the difference between two moving averages. The use of two moving averages in the double crossover method, therefore, takes on greater significance and becomes an even more useful technique. We’ll see how this is done in Chapter 10. One method compares two exponentially smoothed averages. That method is called Moving Average Convergence/Divergence (MACD). It is used partially as an oscillator. Therefore, we’ll postpone our explanation of that technique until we deal with the entire subject of oscillators in Chapter 10.

The moving average can be applied to virtually any technical data or indicator. It can be used on open interest and volume figures, including on balance volume. The moving average can be used on various indicators and ratios. It can be applied to oscillators as well.

There are other alternatives to the moving average as a trend-following device. One of the best known and most successful of these techniques is called the weekly price channel or, simply, the weekly rule. This technique has many of the benefits of the moving average, but is less time consuming and simpler to use.

With the improvements in computer technology over the past decade, a considerable amount of research has been done on the development of technical trading systems. These systems are mechanical in nature, meaning that human emotion and judgment are eliminated. These systems have become increasingly sophisticated. At first, simple moving averages were utilized. Then, double and triple crossovers of the averages were added. The averages were then linearly weighted and exponentially smoothed. These systems are primarily trend-following, which means their purpose is to identify and then trade in the direction of an existing trend.

With the increased fascination with fancier and more complex systems and indicators, however, there has been a tendency to overlook some of the simpler techniques that continue to work quite well and have stood the test of time. We’re going to discuss one of the simplest of these techniques—the weekly rule.

In 1970, a booklet entitled the Trader’s Notebook was published by Dunn & Hargitt’s Financial Services in Lafayette, Indiana. The best known commodity trading systems of the day were computer-tested and compared. The final conclusion of all that research was that the most successful of all the systems tested was the 4 week rule, developed by Richard Donchian. Mr. Donchian has been recognized as a pioneer in the field of commodity trend trading using mechanical systems. (In 1983, Managed Account Reports chose Donchian as the first recipient of the Most Valuable Performer Award for outstanding contributions to the field of futures money management, and presents The Donchian Award to other worthy recipients.)

More recent work done by Louis Lukac, former research director at Dunn & Hargitt and currently president of Wizard Trading (a Massachusetts CTA) supports the earlier conclusions that breakout (or channel) systems similar to the weekly rule continue to show superior results. (Lukac et al.)*

Of the 12 systems tested from 1975-84, only 4 generated significant profits. Of those 4, 2 were channel breakout systems and one was a dual moving average crossover system. A later article by Lukac and Brorsen in The Financial Review (November 1990) published the results of a more extensive study done on data from 1976–86 that compared 23 technical trading systems. Once again, channel breakouts and moving average systems came out on top. Lukac finally concluded that a channel breakout system was his personal choice as the best starting point for all technical trading system testing and development.

The 4 week rule is used primarily for futures trading.

The system based on the 4 week rule is simplicity itself:

The system, as it is presented here, is continuous in nature, which means that the trader always has a position, either long or short. As a general rule, continuous systems have a basic weakness. They stay in the market and get “whipsawed” during trendless market periods. It’s already been stressed that trend-following systems do not work well when markets are in these sideways, or trendless phases.

The 4 week rule can be modified to make it noncontinuous. This can be accomplished by using a shorter time span—such as a one or two week rule—for liquidation purposes. In other words, a four week “breakout” would be necessary to initiate a new position, but a one or two week signal in the opposite direction would warrant liquidation of the position. The trader would then remain out of the market until a new four week breakout is registered.

The logic behind the system is based on sound technical principles. Its signals are mechanical and clearcut. Because it is trend following, it virtually guarantees participation on the right side of every important trend. It is also structured to follow the often quoted maxim of successful trading—“let profits run, while cutting losses short.” Another feature, which should not be overlooked, is that this method tends to trade less frequently, so that commissions are lower. Another plus is that the system can be implemented with or without the aid of a computer.

The main criticism of the weekly rule is the same one leveled against all trend-following approaches, namely, that it does not catch tops or bottoms. But what trend-following system does? The important point to keep in mind is that the four week rule performs at least as well as most other trend-following systems and better than many, but has the added benefit of incredible simplicity.

Although we’re treating the four week rule in its original form, there are many adjustments and refinements that can be employed. For one thing, the rule does not have to be used as a trading system. Weekly signals can be employed simply as another technical indicator to identify breakouts and trend reversals. Weekly breakouts can be used as a confirming filter for other techniques, such as moving average crossovers. One or 2 week rules function as excellent filters. A moving average crossover signal could be confirmed by a two week breakout in the same direction in order for a market position to be taken.

The time period employed can be expanded or compressed in the interests of risk management and sensitivity. For example, the time period could be shortened if it is desirable to make the system more sensitive. In a relatively high priced market, where prices are trending sharply higher, a shorter time span could be chosen to make the system more sensitive. Suppose, for example, that a long position is taken on a 4 week upside breakout with a protective stop placed just below the low of the past 2 weeks. If the market has rallied sharply and the trader wishes to trail the position with a closer protective stop, a one week stopout point could be used.

In a trading range situation, where a trend trader would just as soon stay on the sidelines until an important trend signal is given, the time period could be expanded to eight weeks. This would prevent taking positions on shorter term and premature trend signals.

Earlier in the chapter reference was made to the importance of the monthly cycle in commodity markets. The 4 week, or 20 day, trading cycle is a dominant cycle that influences all markets. This may help explain why the 4 week time period has proven so successful. Notice that mention was made of 1, 2, and 8 week rules. The principle of harmonics in cyclic analysis holds that each cycle is related to its neighboring cycles (next longer and next shorter cycles) by 2.

In the previous discussion of moving averages, it was pointed out how the monthly cycle and harmonics explained the popularity of the 5, 10, 20, and 40 day moving averages. The same time periods hold true in the realm of weekly rules. Those daily numbers translated into weekly time periods are 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks. Therefore, adjustments to the 4 week rule seem to work best when the beginning number (4) is divided or multiplied by 2. To shorten the time span, go from 4 to 2 weeks. If an even shorter time span is desired, go from 2 to 1. To lengthen, go from 4 to 8. Because this method combines price and time, there’s no reason why the cyclic principle of harmonics should not play an important role. The tactic of dividing a weekly parameter by 2 to shorten it, or doubling it to lengthen it, does have cycle logic behind it.

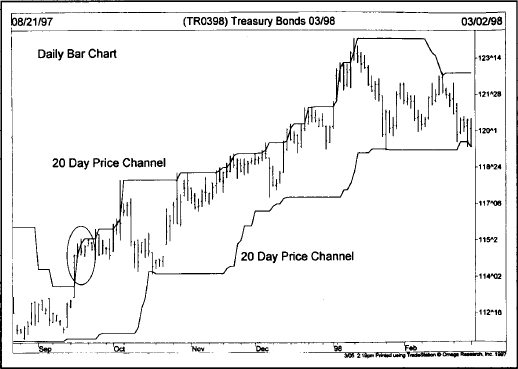

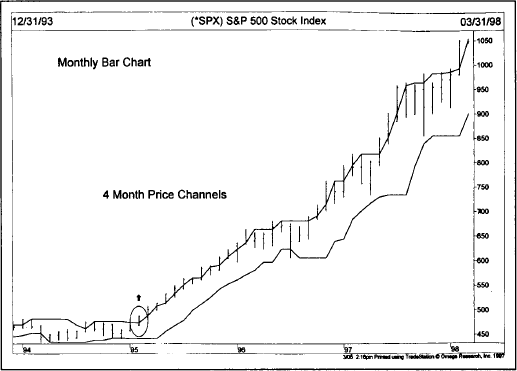

The 4 week rule is a simple breakout system. The original system can be modified by using a shorter time period—a 1 or 2 week rule—for liquidation purposes. If the user desires a more sensitive system, a 2 week period can be employed for entry signals. Because this rule is meant to be simple, it is best addressed on that level. The 4 week rule is simple, but it works. (Charting packages allow you to plot price channels above and below current prices to spot channel breakouts. Price channels can be used on daily, weekly, or monthly charts. See Figures 9.11 and 9.12.)

Figure 9.11 A 20 day (4 week) price channel applied to Treasury Bond futures prices. A buy signal was given when prices closed above the upper channel (see circle). Prices have to close beneath the lower channel to reverse the signal.

Figure 9.12 A 4 month price channel applied to the S&P 500 Index. Prices crossed the upper channel in early 1995 (see circle) to give a buy signal which remains in effect 3 years later. A close beneath the lower line is needed to give a sell signal.

The first edition of this book included the results of extensive research produced by Merrill Lynch, which published a series of studies on computerized trading techniques applied to the futures markets from 1978-82. Extensive testing of various moving average and channel breakout parameters was performed to find the best possible combinations in each futures market. The Merrill Lynch researchers produced a different set of optimized indicator values for each market.

Most charting packages allow you to optimize systems and indicators. Instead of using the same moving average in all markets, for example, you could ask the computer to find the moving average, or moving average combinations, that have worked the best in the past for that market. That could also be done for daily and weekly breakout systems and virtually all technical indicators included in this book. Optimization allows technical parameters to adapt to changing market conditions.

Some argue that optimization helps their trading results and others that it doesn’t. The heart of the debate centers on how the data is optimized. Researchers stress that the correct procedure is to use only part of the price data to choose the best parameters, and another portion to actually test the results. Testing the optimized parameters on “out of sample” price data helps ensure that the final results will be closer to what one might experience from actual trading.

The decision to optimize or not is a personal one. Most evidence, however, suggests that optimization is not the Holy Grail some think it to be. I generally advise traders following only a handful of markets to experiment with optimization. Why should Treasury Bonds or the German mark have the exact same moving averages as corn or cotton? Stock market traders are a different story. Having to follow thousands of stocks argues against optimizing. If you specialize in a handful of markets, try optimizing. If you’re a generalist who follows a large number of markets, use the same technical parameters for all of them.

We’ve presented a lot of variations on the moving average approach. Let’s try to simplify things a bit. Most technicians use a combination of two moving averages. Those two averages are usually simple averages. Although exponential averages have become popular, there’s no real evidence to prove that they work any better than the simple average. The most commonly used daily moving average combinations in futures markets are 4 and 9, 9 and 18, 5 and 20, and 10 and 40. Stock traders rely heavily on a 50 day (or 10 week) moving average. For longer range stock market analysis, popular weekly moving averages are 30 and 40 weeks (or 200 days). Bollinger Bands make use of 20 day and 20 week moving averages. The 20 week average can be converted to daily charts by utilizing a 100 day average, which is another useful moving average. Channel breakout systems work extremely well in trending markets and can be used on daily, weekly, and monthly charts.

One of the problems encountered with the moving average is choosing between a fast or a slow average. While one may work better in a trading range market, the other may be preferable in a trending market. The answer to the problem of choosing between the two may lie with an innovative approach called the “adaptive moving average.”

Perry Kaufman presents this technique in his book Smarter Trading. The speed of Kaufman’s “adaptive moving average” automatically adjusts to the level of noise (or volatility) in a market. The AMA moves more slowly when markets are trending sideways, but then moves more swiftly when the market is trending. That avoids the problem of using a faster moving average (and getting whipsawed more frequently) during a trading range, and using a slower average that trails too far behind a market when it is trending.

Kaufman does that by constructing an Efficiency Ratio that compares price direction with the level of volatility. When the Efficiency Ratio is high, there is more direction than volatility (favoring a faster average). When the ratio is low, there’s more volatility than direction (favoring a slower average). By incorporating the Efficiency Ratio, the AMA automatically adjusts to the speed most suitable for the current market.

Moving averages don’t work all of the time. They do their best work when the market is in a trending phase. They’re not very helpful during trendless periods when prices trade sideways. Fortunately, there’s another class of indicator that performs much better than the moving average during those frustrating trading ranges. They’re called oscillators and we’ll explain them in the next chapter.

*See Bibliography