|  |

#

Jack runs ahead, as he always does. How anyone can keep a close eye on an eight-year-old is a mystery Ellie would like to solve, but this morning is not the time or the place. She increases her pace up the steep, narrow path that leads to the top of the paddock, ears straining to hear how far ahead Jack has run.

“Wait for me!” she calls. “Wait at the gate!” Her words dissolve in the thick mist, cloaking her in a cloudy quilt, as if she never said them at all. The fog is good at blanketing noise, making the world invisible. It smells good, fresh and earthy, like a rain forest should.

Ellie keeps the torch focused on her feet, wary of the gnarled roots that embroider the cleared ground, nearby trees reaching out to reclaim what was theirs. And cow pats, though they haven’t seen any cows in the few days they’ve been here. The website showed quite lovely photos of huge black-and-white heads lined up at the cottage fence, but Ellie is happy to do without that aspect of country life.

“Jack!” she calls again. A muffled laugh from somewhere ahead. She hopes he’s not going to play that drop-bear game again, where he jumps down on her from up a tree. She’s on her guard, torch tight in both hands, ready to shine it at him.

Ellie reaches the skewed wooden gate that separates this paddock from the Beechy Line. No sign of Jack, but she’s come so far up the hill, the fog is lighter. He can’t be too far ahead. He wanted to show her things up here, things that look best at dawn or dusk.

She clambers through the uneven bars to stand on the gravel pathway. At this early hour there are no cyclists, and it’s unlikely any walkers would have come this far along the track from Gellibrand yet. Ellie looks back down the steep slope to the holiday cottage she chose because Jack was so excited about the remnants of the old Beechy Line railway nearby.

Something swipes past her head, startling her even though it has to be her son playing pranks. A flash of wings and a flurry of air tell her she’s wrong, and the next moment she’s jumping again as a kookaburra cracks out a cascade of mocking laughs overhead. Jesus. No wonder the first Europeans thought madmen were attacking them.

“Jack!” she calls again, a bit annoyed, though the behaviour of the wildlife is not his fault. The sky is much lighter and she switches off the torch, frowning down at the uneven track. Uphill to the old bridge, he told her last night, so she starts off in that direction.

“Hurry up Mum! Don’t be such a slowcoach.”

Ellie’s heart pounds once, then settles. There he is, up ahead at the next curve, his rosy cheeks almost as red as his parka. “I can see you, cheeky boy. How far to the bridge?”

“Long way,” he calls over his shoulder, and disappears around the bend. “George is gonna meet us there.”

George is a local kid, the one who’s been telling Jack all about the wonders of the old rail trail, promising wombats and echidnas if they get up here early enough—even a platypus in Charley’s Creek, if they’re lucky. Ellie hasn’t met George or his parents, but Jack told her that George likes to play with the children of families staying at the cottage. He often hangs around waiting for visitors, says Jack, who’s taken a big shine to him. This last few days, George and George-says feature in all his stories.

The fog—or maybe low clouds, she supposes, as the track is so high up the mountain—drifts in and out like a veil, wafting chills over her every so often. She follows the sound of Jack’s running and his occasional cries of ‘keep up’. She’d prefer to have him in sight, but he’s eight now and wants to run. He’s almost too big for a goodnight kiss, which is a thing Ellie finds especially disheartening.

She continues uphill, the curving nature of the track preventing her from seeing far ahead. She takes a moment to marvel at how they built a railway through these hills, the terrain so steep and wet. On her left, cuttings lift high above the track, dripping with dew and the last of yesterday’s rain. Huge trees—regrowth from the old timber trade—reach high into the mist: mountain ash, stringybark, beech, wattle, the odd apple tree sprung from a discarded core.

On the low side of the track the ground drops away into abrupt ravines, complete with miniature waterfalls soaking down into the tree ferns. Those ferns are beautiful, their curled new growth exquisite, rising above the bracken and blackberry that border the track.

The forest opens a little to her left. A small clearing—what used to be a clearing—shows the decaying trunk of an enormous tree, a dead giant lying at an angle to the track. A ballast siding, that’s what it was—Ellie remembers Jack saying so, information courtesy of George, no doubt. Ellie smiles. What a colossal tree that must have been. No wonder the timber fellers loved this forest.

But it’s sad, too. No way any tree will grow to that girth in the future. She shakes her head, stops to listen: boyish laughter ahead. She presses on up the hill, hands now dug deep into the pockets of her jacket. The dawn air is freezing. Her nose is cold and she has to stamp her feet every now and then to feel her toes.

The track bends again, and Ellie sighs. So much for a nice mum-and-son holiday, a handful of days to put locked-down home schooling behind them and get ready for the new year. She’s hardly seen Jack. All his energy directs him outside, and he’s now—so it seems—too old for his mother to tag-along. Ellie remembers a time when she wished with all her heart that he could amuse himself a bit more, keep out of her way. Be careful what you wish for, she thinks.

But this is strange new territory, and while she agrees with building resilience and independence and initiative, something about the still, cold air gives Ellie the shivers. Not just the temperature, but how the sun stalls on the far side of the mountain, as if sunrise will never arrive. Plus the fact she’s been walking uphill for the better part of thirty minutes and she’s still chilled to the bone.

The Beechy Line is not quite the jolly morning walk she expected.

“Jack!” she calls. “Jack! Where are you?”

The kookaburra cackles directly overhead, and there’s an echo of laughter further up the track.

Ellie stops to cup her hands around her mouth. “JACK!”

A squadron of rosellas erupts out of the undergrowth. The ground shakes with the beat of kangaroos, bounding away with a sound like a muffled jackhammer. Straining her ears above the wildlife, Ellie hears Jack’s voice.

“Up here, slowcoach, by the bridge—what—” The words fracture into a stifled cry, and Ellie bolts toward the place.

Cold air makes her throat and lungs ache as she pounds up the track, eyes wide with fear. “Jack!” she gasps, but the only answer is a scolding chitter from the scrub wrens and another guffaw from the kookaburra. Around the next bend the track descends, and Ellie gulps in snatch of icy air turning her head this way and that, desperate for a sight of him. “Jack!” she calls, dashing down the incline, slipping on the muddy sections, staggering on the gravel, sobbing with terror. Another curve reveals the worn and warped planks of an old bridge, the bridge Jack told her about.

Here’s the bridge, but no Jack. The place looks untouched, like a postcard from a bygone age. There’s nobody to be seen. She lets out a despairing cry that echoes back from the sides of the cutting, chill and eerie.

Ellie stops, bends double, tries to drag in a breath past the pathetic, terrified flapping of her heart. The bridge is huge and disintegrating. Ferns and moss drape its broken spans. Saplings push through the large gaps that perforate it. The old bridge stretches imperfectly across a huge ravine where a narrow waterfall dashes down the mountain.

Surely, surely the boys didn’t try to cross that rotted thing? Surely?

“Jack!” she calls, and then “George!” The water gurgles and splashes below. The damn kookaburra chuckles in reply. Ellie yells, anger bolstering her fear. “Aaargh! Jack, wait till I find you! Just you wait!”

She steps warily onto the first span, leaning forward to peer between the moss-covered beams. There’s no sign of anyone below—no red parka, no boyish limbs. Ellie lifts her head to look at the bush on the other side of the ravine. Nothing.

She turns from the bridge, fists clenched. She fights dread and rage. How could a sunrise walk in the rainforest go so wrong? Damn Jack and his stupid friend. Damn the wombats and the platypus and the scarlet robins. Damn her for listening to his pleading. Damn her for—

Ellie stumbles back, mouth gaping, staring at the biggest kangaroo she’s ever seen. It must be over two metres tall, standing on the track and blocking her way forward.

Lurid images of injured runners flood her mind, blaring about roo attacks. The kangaroo’s face is impassive, its huge dark eyes fixed on her, muzzle down in disapproval. The hunch of its shoulders, the bulging chest muscles, all make her very aware she’s an intruder. This is his rainforest.

Ellie has never been so frightened.

She scrambles to her feet, crouching low as she retreats. The buck kangaroo never takes his gaze from her; he even leans forward as if considering a leap. Ellie puts up both hands in supplication, can’t help whispering, “Look, see, I have no weapon, I’m no danger to you. I’m leaving now, but, but, my son! Please, please.” She doesn’t know what she’s asking, except perhaps that the animal will let her past, let her find Jack.

The buck lifts his head and lets out a barking growl, loud enough to cover the gushing waterfall. Ellie takes another step back and the kangaroo barks again. Off to the side, as if in answer to the king roo’s command, the mob booms through the forest again, twigs snapping and branches swishing as they go. But—wait—was that the sound of a boy laughing, heading deeper into the bush among the mob? Ellie calls out for Jack, and the kangaroo takes a bound toward her. She covers up, crouching low, and in another moment he’s gone clear over her, crashing through the undergrowth in the wake of the mob.

She stays low, arms over her head, dragging in air that tastes of fear and forest. Her face is running with tears. She’s sobbing. Fright and anger and frustration choke her voice. “Jack,” she whispers. “Oh, Jack!”

***

The ambulance crew are kind, kinder even than the searchers who’ve come from Colac, Apollo Bay and as far as Geelong, arriving in batches throughout the day. It’s shock, they tell her, and exposure. That’s why she’s shaking so hard.

They shepherd her toward the trolley. Just to the hospital in Colac, don’t worry. The doctors will check you out, make sure you’re okay.

“But Jack!” Ellie cries.

“They’ll bring him,” says the paramedic, soothing. “You can see him there. He’s going to Colac too. It’s best you don’t look now, really. You can visit the morgue later.”

Ellie wails. “No!”

“Sweetheart, he’s dead. He’s had a nasty fall, and then the mob’s gone over him—”

“Leave off!” says someone else.

“Sorry, sorry, sweetheart. Time to go. Come on now.”

Ellie goes a few steps, her heart and mind still, vacant, empty. Then a single word: Jack, Jack, Jack . . . Suddenly she stops, pulls against the paramedic’s guiding hand.

“What about George? Did they find George?”

Murmuring and whispering, she can’t catch the words. Then someone says, “Let’s ask Danny, he’s a Beechy boy.”

There’s jostling and more whispers. Ellie gets the idea that they’ve already dismissed George, that they never even looked. Her heart squeezes with pain.

One of the searchers comes forward, a tall, thin fellow with sandy, receding hair. “Danny,” the paramedic asks him, “Any chance there was another boy up here? Ellie says she remembers somebody called George, eight or so. He came to play with the boy, with her son, I mean. Anyone of that name round here?

Danny frowns, his face pale under a galaxy of freckles. He seems embarrassed, but at least he looks her straight in the eye. “Sorry, missus, nobody called George around these parts. There’s no kids on the farm up there, the one past the bridge. George was the name—” He stops, looks guiltily at the ambulance crew. “There was a George here once, came picnicking with his family one summer. Got lost in the bush. Years ago, if it ever happened.”

“Oh, that George!” says the paramedic with his hand on Ellie’s arm. She looks at him in bewilderment. He coughs. “That’s just a story, right Danny? What our parents told us to keep us from wandering. Don’t be like George the Beechy boy, or you’ll get lost and never come home. Something like that.”

“No,” says Ellie. “He was a real boy, he was. I heard him. I heard . . .”

She hears nothing else above the roar of her blood, pumping knowledge to her reluctant brain, her devastated heart.

Her Jack. He’s now a Beechy boy.

––––––––

About the Author:

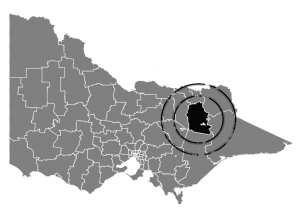

Clare Rhoden lives on Bunurong country in suburban Melbourne. Author, editor and reviewer, Clare started writing early and never stopped, although she is often interrupted. Her novels are published by Odyssey Books, and her short stories and non-fiction pieces have appeared in Australian and international journals. Her Doctor is Tom Baker and her star sign is Cancer. Come meet her at clarerhoden.com

The spectacular views from Mount Buffalo make it easy to overlook the dark secrets of the mountain.