CHAPTER 6

SCHOOL DAYS

THE nine young men were placed on orders to attend the Submarine School that had been established right there in San Diego.

“The ‘real’ Navy Submarine School was in New London, Connecticut,” Smitty said, “but we weren’t going there. The demand for new men was too great at this time, so an improvised Sub School was set up at the San Diego Destroyer Base.”

It wasn’t much of a school. There were no textbooks; each student had to make his own workbook. Their instructor was a chief off Cachalot, an old “V”-boat. For the first two weeks, the chief showed them pictures and described the various hydraulic, electrical, low-pressure and high-pressure air lines, and other systems and principles that operated the current, state-of-the-art submarines. The students had to draw and write everything in their workbooks. “After two weeks of classroom work, the chief took us down to the docks where Cachalot, which was our school boat, was moored,” Smitty said.

Over the course of the next few weeks, Smitty got to know his eight fellow classmates well. Besides Shineman, there was tall, good-natured Bill Partin from Oregon; handsome, blond Bill Quillian from Washington state; Montanan Jim Biggars, whose dark complexion and surly look belied his sunny, easygoing personality; Jim Koster, who brought a relaxed Texas demeanor with him from Houston; Hank Brown, a Los Angelino; Bob Kaminsky from Chicago; and San Franciscan Jim Caddes, who seemed the most cynical and worldly of the group. Smitty hung out with them all but most enjoyed Bill Partin’s company.

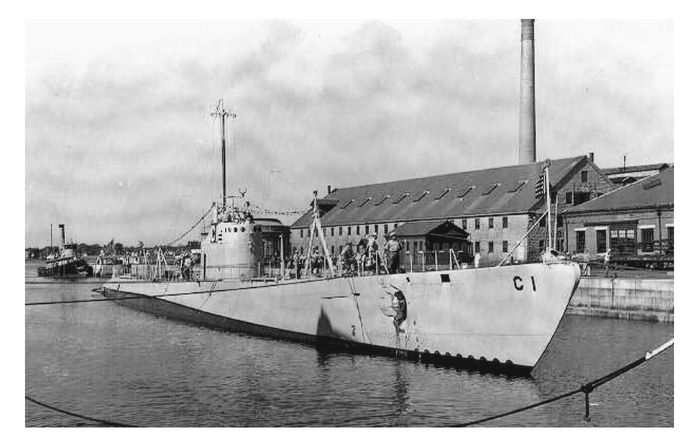

U.S.S. Cachalot, photographed 9 July 1934 at Portsmouth, NH.

(Courtesy Naval Historical Foundation)

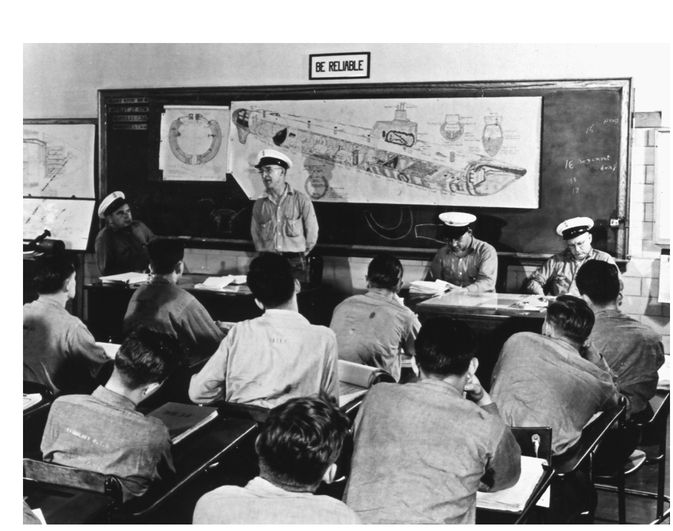

Fledgling submariners learning the basics at Submarine School,

New London, Connecticut, 1943.

(Courtesy National Archives)

The students were schooled in the theory of submarines. The concept behind the submarine was simple yet ingenious: create a hollow, watertight chamber capable of withstanding thousands of pounds of water pressure that could intentionally be sunk by filling large ballast tanks with seawater to create “negative buoyancy.” The chamber could then be raised by using compressed air to force the water out of the ballast tanks. Diesel engines would be used to rotate the propellers when the craft was on the surface and battery-powered electric motors would take over from the diesels when submerged. There was nothing to generate oxygen to keep the crew alive; the ambient air brought into the submarine while the hatches were open during surface running supplied enough oxygen to last eighty men for nearly a day.

To enable the commander of the submarine to visually survey the sea around him without being obvious and giving his position away, the submarine was fitted with optical devices known as periscopes that could be raised and lowered at will while the bulk of the vessel remained hidden below water. The sub could communicate with the outside world through the use of radio.

Of course, a vessel that merely submerged and surfaced would be good only for reconnaissance work; to turn the submarine into a man-of-war required the addition of armament. Tubes fore and aft would launch torpedoes, and deck-mounted guns and machine guns would be used for offensive and defense actions while surfaced.

1Everyone in the U.S. Navy believed American subs to be the best in the world. Mike Geletka, a sailor aboard

Harder (SS-257), remarked, “I’ve been on English boats and Dutch boats and German boats—I was on the U-505

15 when they brought it back in ’46; the German U-boats were a hunk of junk. The U.S. got a late start in submarine design but we advanced a lot further than they did. I don’t care what anybody says, our boats were Cadillacs compared to the others—the others were like Model Ts. We got three meals a day, we had our own bunks and our own showers; we had double hulls. We had no room on board, but we had more than the others had. Ours were just better boats all around. Whoever designed that

Gato-class did a great job. Then came the

Balao and then the

Tench-class, the thick-skins, that were even better.”

2The World War II “Fleet” submarine of the Gato (which was built from 1941 to 1943) or Balao-class (built from 1943 to 1945) was as technologically advanced for her time as any weapon of war ever invented. The standard Gato-class Fleet submarine was 312 feet long, had a beam of twenty-eight feet, a surfaced keel depth of sixteen feet, displaced more than 1,500 tons, and carried twenty-four torpedoes. She could travel thousands of miles without refueling or docking to take on food or supplies.

The submarine was also a prime psychological weapon. It could, at the first sign of an enemy ship or convoy, glide beneath the surface and carry out her deadly attacks at periscope depth or, when sighted and attacked, dive deeply to escape the effects of bombs and depth charges. She could then resurface at another location to resume her assault—or simply disappear from the area as silently and stealthily as she had come.

Cutaway view of Fleet-type submarine (Balao class).

(From Roscoe, Submarine Operations in World War II. Reproduced by permission of publisher)

Like a nervous native rowing a raft on a river full of crocodiles, the fear of being attacked was always there, always lurking just beneath the surface. There were Japanese captains out there who had spotted the slim cyclopean periscopes peering their way, who had heard the ominous clank of malfunctioning torpedoes bouncing off their hulls, who had wondered how long their luck would hold out. For sailors on board enemy vessels, the mere thought that a submarine might be lurking unseen nearby and preparing, at any moment and without warning, to send them to Davy Jones’s locker was nerve-racking in the extreme.

The bow of a Fleet submarine contained the forward torpedo room with its four or six torpedo tubes (and, when armed for a combat patrol, sixteen torpedoes), fourteen hinged bunks suspended by chains from the walls, or bulkheads, and an overhead hatch leading to the forward escape trunk, or compartment; during combat operations the bunks were swung out of the way to maximize working space.

Submarine battery.

(Whitlock photo)

Near the center of the boat was “officers’ country”—the cramped living quarters and dining area for the ensigns, lieutenants, and commander. The ward room served many functions, including mess hall, meeting room, recreation hall (for cards, cribbage, chess, and checkers). There was also a pantry and the “state-rooms” for the officers and chief petty officer.

Directly beneath officers’ country and the control room was the largest space on board: the forward battery compartment and pump room. In this compartment stood 126 huge lead-acid batteries, each weighing more than a ton. It was the batteries that enabled the submarine to operate underwater. In the adjacent pump room were the air compressors, hydraulic pumps, air-conditioning compressors, and trim and bilge pumps.

When submerged, the submarine ran solely on battery power—but considerably slower than when running on the surface. Underwater, she had a maximum speed of nine knots, but because prolonged travel at that speed would deplete her batteries within thirty minutes, submerged speed normally did not exceed three knots. A submarine could travel roughly a hundred miles submerged.

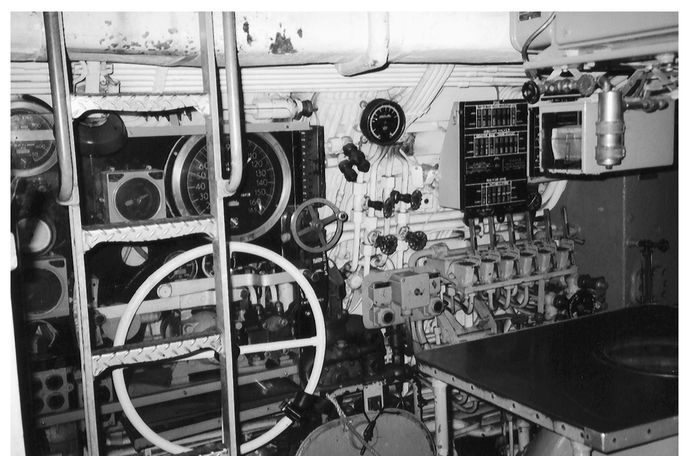

Directly aft of the officers’ quarters and below the conning tower and bridge was the control room. As its name suggests, this was the location from which the submarine was controlled by the captain when submerged. The right, or starboard, side was called the “dry” side of the control room, for here the electrical and air controls were located. The left, or port, side was known as the “wet” side because it contained the controls for the hydraulic as well as the trim and drain systems.

Here, too, was located the diving station from which, through the use of large control wheels, the boat could be submerged or surfaced. Two large “steering wheels” faced the port bulkhead and were operated by two planesmen. These wheels controlled the “elephant ears,” or bow and stern planes, which determined the angle at which the submarine dove or surfaced. Immediately behind the bow planesman’s bench was the ladder to the bridge and conning tower.

Located on the bulkhead in this compartment were two panels known as the “Christmas tree,” for the red and green indicator lights on these panels showed at a glance if any hatches were open or closed. If a hatch was open, an indicator light glowed red; if it was closed, the light was green. To safely submerge, all indicator lights needed to be green.

The control room also contained the auxiliary steering station, general announcing equipment, and interior communications switchboard. In the center of the room stood two tablelike objects: a plotting table or dead-reckoning tracer that mechanically plotted the boat’s latitudinal and longitudinal position, and the master gyrocompass that floated on gimbels and was the essential tool for navigation. Located above the gyrocompass were the fathometer, which measured the depth below the keel, and the bathythermometer, which gave a reading of the outside water temperature—vital for locating cold layers of ocean water that partially negated the enemy’s underwater submarine-finding equipment known as sonar.

View of complex array of switches, gauges, dials, and machinery in a submarine control room (U.S.S. Pampanito). The black-panel box at upper right is the “Christmas tree.” The ladder leading to the conning tower is visible at left. (Whitlock photo)

Aft of the control room was the incredibly cramped radio room, stacked from deck to overhead with radio equipment. One man—preferably of small stature—could just barely squeeze into the chair and desk thoughtfully provided for him.

To the aft of the radio room was a relatively spacious room: the galley and crew’s mess hall. It was said that to compensate the submarine crews for their dangerous work and less-than-ideal living conditions, the Navy provided them with the best food of any branch of service. Because of the limited space, the crew ate in shifts of twenty-four men, while cooks and bakers worked around the clock to feed them. Most boats had two cooks and one baker. The cooks worked a full day every other day, and the baker worked every night, baking bread and rolls and pastries.

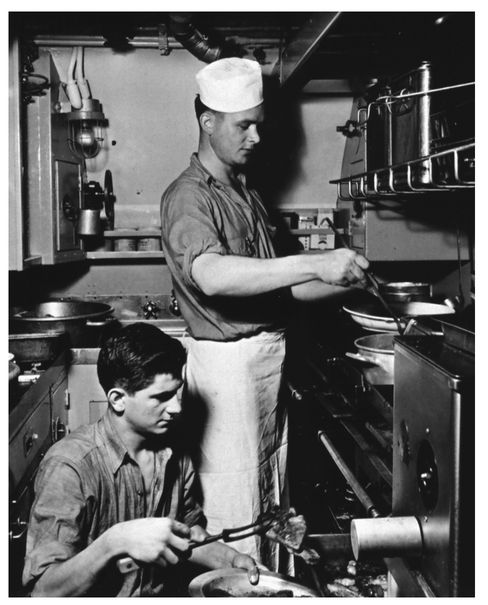

Two cooks aboard U.S.S. Batfish share cramped galley

working space as they prepare a meal for the crew.

(Courtesy National Archives)

The galley also doubled as a recreation center. Here men could relax, read, play cards or board games, and write letters home.

Below the galley deck was a large freezer and refrigerator for cold-food storage. Since storage space was at a premium, every available space, opening, shelf, and cubbyhole on a submarine was crammed with crates, cartons, boxes, barrels, and bags of foodstuffs. A submarine leaving port more resembled a seaborne grocery warehouse than it did a warship. The enlisted crew normally had use of two toilet compartments, or heads; one of them was totally filled with crates of food, and could only be used once all the food taking up space in that head was consumed.

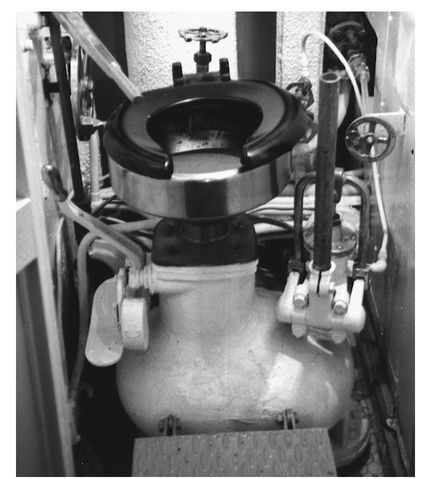

3One of the most complicated pieces of apparatus on board a sub was the commode. Smitty recalled, “When using the head, there were certain vital steps that had to be taken in the correct sequence or you—or the guy after you—would wind up covered with shit.”

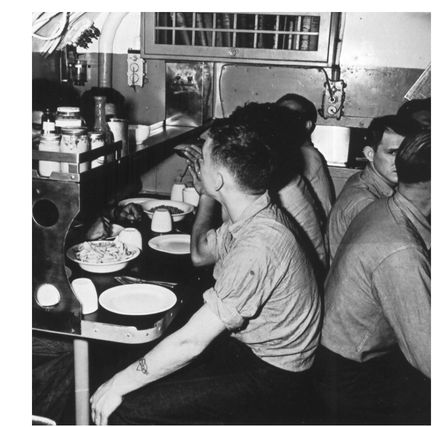

4Crewmen aboard U.S.S. Batfish squeeze into

the tight galley mess area.

(Courtesy National Archives)

The toilet (U.S.S. Cobia).

(Whitlock photo)

A brass plaque mounted on the inside of the hatch spelled out exactly how the toilet was to be operated:

Before using, see that Bowl Flapper Valve A is closed, Gate Valve C in discharge line is open, Valve C in water supply line is open. Then open Valve E next to bowl to admit necessary water. Close Valves D and E. After using, pull Lever A, release Lever A. Open Valve C in air supply line. Rock Air Valve Lever F outboard to charge measuring tank to 10 pounds above sea pressure. Open Plug Cock B and rock Air Valve Lever F inboard to blow overboard. Close Valves B and C. For pump expulsion, open Plug B. Pump waste receiver empty. Close Plug Cock B. Close Valve C. If on first inspection, the expulsion chamber is found flooded, discharge the contents overboard before using the toilet.”

5

Below the deck were the magazines, where ammunition for the deck gun and machine guns was kept; special hatches enabled men in the magazine to hand the ammunition up to the top deck and then to the gunners.

To the rear of the galley was the main crew’s berthing area, called the “after battery.” Thirty-six bunks, stacked three high, gave the men a place to sleep, but because there were not enough bunks for each man, the men had to “hot-bunk,” i.e., use a bunk that had been vacated by a man who was on duty.

Directly behind the bulkhead of the berthing area were two large, stainless-steel evaporator units that turned seawater into about 1,000 gallons of distilled water per day. The first priority for this purified water was to keep the lead-acid batteries filled. The second priority was for drinking and cooking. The lowest priority was for showering (there were two shower stalls on board); on long patrols, the men were allowed to shower—maybe—once every two weeks; on many patrols, however, it was not uncommon for men to go a month or more without showering.

Next came two engine rooms. The H.O.R. (Hooven, Owens, Rentschler) engines—often called “whores” by the crewmen who had to maintain them—had proven to be supremely unreliable, so the new Fleet boats were equipped with four, ten-cylinder, 1,600-horsepower Fairbanks-Morse or General Motors opposed-piston diesel engines, each the length of an automobile, that gave a sub a maximum surface speed of twenty-one knots (about twenty-four miles per hour). The diesels simultaneously charged the storage batteries and powered the lights, food refrigeration, air-conditioning, radar, communications equipment, etc. Most older subs that were kept on active duty were retrofitted with the new engines.

The men who worked in the engine rooms—usually refereed to as the “black gang”—had it the worst of anyone on board. Not only did they have to endure the constant, deafening roar of the diesel engines for hours on end when the submarine was operating on the surface, but they also had to endure the parboiling temperatures given off by the engines; 130-degree heat was common in the engine compartments. But the rest of the sub was little better; in most other parts of the boat the temperature remained at or above 100 degrees Fahrenheit when the diesels were running. It is no wonder that most of the submariners worked only in sandals and skivvies while on patrol. And it is not hard to imagine the reeking odor on board a submarine created by the unwashed bodies of eighty sweating, unbathed men.

A submarine crewman reads a book in his bunk just

inches above one of the torpedoes.

(Courtesy National Archives)

Frank Toon, who served aboard

Blenny (SS-324), recalled that submariners quickly lost their sense of smell once in the boat. “You never really noticed any smells after you got aboard. Diesel fumes, body odor, cigs, et cetera—all blended in to make our environment. You got used to it and never noticed it. Other people would notice it—those who didn’t live on subs. I remember an incident in the ship’s service store in the late forties. There were a half dozen of us who had walked up to get things we needed—toothpaste, foo-foo [deodorant or cologne], et cetera. At the time we were in line there were a couple of women (not sub wives!) who were also in line at the cashier. Although we were all clean, the women could smell us, and made no bones about it with a remark loud enough for all us to hear—about stinking sub sailors! As this was the sub base ship’s service, and they were here shopping as only a courtesy, my boss, a quartermaster chief, really let fly at them!

Whooooeeeeee—they couldn’t get out of there fast enough. So much for smells. Guess it would have been pretty raunchy to anyone not used to it!”

6

Frank Toon.

(Courtesy Frank Toon)

Just forward of the final section of the submarine—the after torpedo room, with its four tubes, eight torpedoes, and twelve bunks—was the maneuvering room. When the captain issued an order from the bridge, conning tower, or control room to change course or speed, it was conveyed to the maneuvering room, where large brass levers were thrown manually to comply with the order. Here, too, the command to dive or surface was relayed, and the switch to the appropriate propulsive power—diesel or battery—was thrown. Large, twin propellers outside and directly below the aft torpedo room provided the thrust needed.

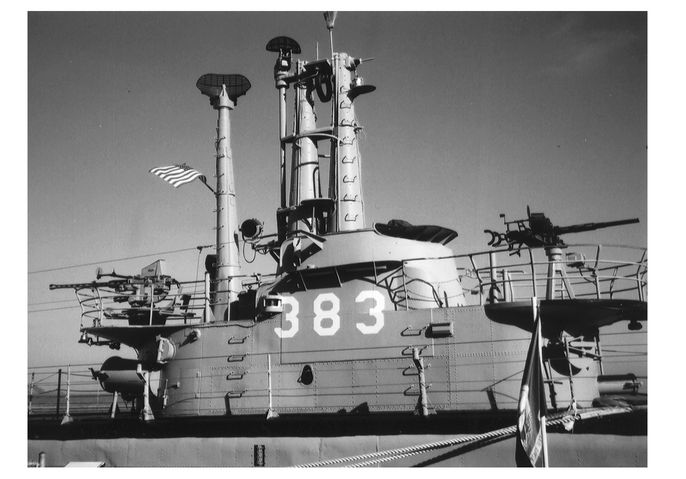

Abovedecks, the submarine sported a bridge, conning tower, periscope, periscope shears, radar equipment, and armament—usually either a three-or five-inch deck-mounted gun and two twenty-millimeter machine guns.

Because the submarine by itself is little more than a reconnaissance vehicle, inflicting damage on the enemy’s ships and coastal installations required something better than the type of spar-mounted explosive charge that had wrecked both the hunter and the hunted during the Civil War. It needed self-propelled projectiles that could blow up enemy vessels without endangering itself. It needed torpedoes.

View of bridge (U.S.S. Pampanito).

(Whitlock photo)

The standard American submarine torpedo during the First World War was the Mark VII, which had a diameter of eighteen inches. The Mark VII, with its 326-pound warhead, had a maximum range of 5,000 yards and a top speed of thirty-five knots. But the Mark VII was an inferior fish; its small warhead was insufficient to blast a hole in the thick armor that protected the hulls of most warships of the day. Because torpedo-firing surface ships were using twenty-one-inch Mark X torpedoes, it made sense to build new submarines capable of firing this bigger weapon.

By the time the S-boats came into service in 1920, they were armed with the Mark Xs, which now carried 497 pounds of explosive and had a maximum effective range of 3,500 yards at thirty-six knots.

Other nations, too, were working on improving their armament. The Japanese, for example, were busily developing monster torpedoes such as the twenty-four-inch, Type 93 “Long Lance” oxygen-powered torpedo with a 1,720-pound warhead, which was primarily designed to be launched from destroyers. Many weaponry experts have rated this giant pickle the most effective torpedo up to that time. Japanese submarines were fitted with a slightly smaller version—the twenty-one-inch, Type 95 wakeless, oxygen-propelled torpedo that carried an 893-pound warhead (later increased to 1,213 pounds) and had a range of five miles at forty-nine knots. The speed and size of these two types ensured that any target in its path would be demolished.

7All nations in the torpedo-designing contest had abandoned the straight-running fish, which required that the submarine be pointed directly at its target or intercept point, and replaced them with torpedoes that had manual gyros that could be set and enable the torpedo to follow the “dialed-in” setting.

Another innovation, exclusive to the U.S. Navy, was an electromechanical torpedo data computer (TDC). The Bureau of Ordnance at the Torpedo Station at Newport, Rhode Island, was also working to produce the next generation of twenty-one-inch torpedoes that would have a larger warhead, higher speed, and a magnetic proximity exploder that would set it off whenever it came close to a target, rather than be required to actually strike the hull.

The U.S. Navy’s TDC was leagues ahead of anything employed by any other nation at that time, and was a precursor to the highly sophisticated computerized target-tracking and firing systems in use today. Whereas other navies had basically done nothing more than mechanized the functions of the “Is-Was” manual computer (a type of circular slide rule used to compute firing angles), the American Navy copied from the complex electromechanical computers that battleships used to direct the aiming and firing of the main guns. The TDC, located in the conning tower, was able to keep track of the submarine’s and target’s position, course, and speed, and calculate the torpedo’s track to hit the target. The TDC also transmitted the constantly updated information directly to the torpedoes.

But, of course, everything hinged on the torpedo actually exploding once it reached its target—something that had been less than a certainty since the war began.

In the early months of World War II, the Germans had used magnetic exploders but found them unreliable; U-boat commanders were ordered to deactivate them. The kill rate of their torpedoes suddenly shot back up. The U.S. Navy’s BuOrd, however, kept its collective head in the sand, insisting (as it had with the deep-running problem) that there were no shortcomings with the Mark VI magnetic exploder that more and better training of the submarine crews couldn’t fix.

The main problem, however, was not the crews but BuOrd. The organization refused to recognize two vital facts: one, that the earth’s magnetic field varies in various parts of the world, and two, that a steel-hulled ship could be demagnetized to make it less vulnerable to being sunk or damaged by a torpedo armed with a magnetic exploder. And so, pickles that came close to enemy hulls, and even actually struck them, did little more than scrape off a few barnacles, cause enemy captains an extra measure of worry, and give American submariners sleepless nights.

8

HIGHLY sophisticated submarines require highly trained specialists to operate them, and submariners soon became known as the elite of the elite. The submarine historian Norman Polmar noted, “Unlike aviators, who were awarded wings after graduating from flight school, a New London graduate went to sea and qualified in a boat before being awarded his coveted dolphin insignia”—silver for enlisted men and gold for officers.

9The officers and enlisted men aboard a submarine were assigned to specific tasks. Among the officers, one was the chief engineer, another the torpedo and gunnery officer, and a third the communications officer, while the lowest-ranking officers served as their assistants. The executive officer was also the navigator. The commander, obviously, was responsible for the overall operation of the boat and its crew, was personally in charge of combat operations, and oversaw the activities of everyone else.

There was an easy familiarity between submarine officers and enlisted men virtually unknown in the other services and other segments of the Navy. There were very few signs of formality or military courtesy within the intimate confines of a sub. Rank was forgotten; there was no saluting, and the use of the term sir was kept to a minimum.

Carl Vozniak, an electrician’s mate first class aboard

Finback (SS- 230), remarked, “You never say ‘yes, sir’ or ‘no, sir’ to any of the officers. The only officers you ever say ‘yes, sir’ or ‘no, sir’ to are the old man [commanding officer] and the officer of the day. All the others you just call by their last names. Not even ‘mister’; just ‘Jones’—‘Hey, Jones.’ ”

10While the officers had their own space aboard a sub, it could by no stretch of the imagination be called “spacious,” or “luxurious” or “private.” Indeed, to go from one end of the sub to the other it was necessary to pass through the officers’ living quarters, known as “officers’ country.” Only the commander had his own private cabin—which was only slightly larger than a phone booth. From his less-than-normal-size bunk, the skipper could view a wall-mounted compass and depth gauge so he could immediately discern the boat’s attitude whenever he was in his cabin. He also had a communications system that enabled him to speak with persons in any other part of the boat without leaving his stateroom. If “rank has its privilege” in other branches of service, such privileges were conspicuously absent aboard a submarine.

No matter how brave a man might be, the claustrophobic, artificially lit interior of a submarine could be unnerving in the extreme. Although a submarine was the length of a football field, it was barely wider than a school bus. There was precious little wasted space. Lines, hoses, and pipes ran the length of the boat, and hardly an inch of wall space wasn’t covered by a bank of switches, gauges, circuit boxes, indicator lights, storage lockers, or bookshelves for hundreds of manuals. Every room, galley, head, and passageway was only as large as absolutely necessary for human beings to live, sleep, eat, move, communicate, and defecate. Due to the preciousness of fresh water, shaving, showering, and the washing of clothing were verboten, and officers and men alike usually stripped down to their skivvies during the long, hot patrols. On some patrols, men worked in the buff.

In short, every American submarine was a formidable, highly technical fighting machine with a singular purpose: to hunt down enemy ships and destroy them. And Smitty was excited for the opportunity to be a part of it all.