CHAPTER 8

READY FOR WAR

IT was a thing of beauty.

Eighteen-year-old Seaman First Class John Ronald Smith watched with fascination as the ancient artist—he must have been fifty or sixty—intently traced the inked, stenciled outline and converted the drawing into a gorgeous, three-color tattoo. Taking shape was an American eagle, its wings spreading across six inches of Smith’s right forearm, its talons clutching a four-inch-high anchor upon which was emblazoned the letters USN.

All the booze that Smitty and his pal Bud Shineman had consumed during their night of hell-raising in downtown San Diego helped to dull the killer-bee-attack pain of the four reciprocating needles that jabbed away like a sewing machine in slow motion, riding along the black lines and squirting tiny droplets of color just beneath the skin. Occasionally the artist would wipe off the blood that beaded to the surface from each epidermal perforation.

Shineman, perhaps the more sober of the two, looked on with some trepidation. “Tattoos are against regulations, Smitty,” he had earlier warned his friend in an effort to dissuade him from going through with the procedure. “You could get syphilis from it,” he added.

Smith scoffed. “It’s not against regulations to get a tattoo—only to get syphilis,” he replied. Smitty recalled how often he had studied his dad’s tattoo, garnered while he was a sailor during World War I, and could hardly wait for the day when he could get his own. For many sailors, getting that first tattoo was as much a rite of passage into manhood as that first sea voyage or that first exchange of gunfire with an enemy warship or that first visit to a whorehouse.

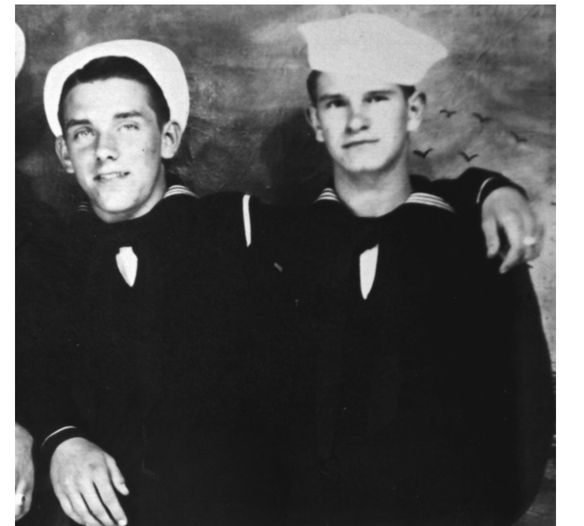

Smitty (left) and his friend Bud Shineman.

(Courtesy Ron Smith)

When he was done, the artist told Smitty to keep the tattoo well greased with Vaseline until the scabs came off—which would take about three or four weeks. His arm aching as though he had just been wounded by a tiny Japanese machine gun, Smitty smiled bravely, paid the artist three dollars, and walked out with Shineman into the cool San Diego night, hoping that he would soon have the chance to go home on leave and show his dad his proud new work of arm art before his submarine—whichever one he might be assigned to—shoved off into the vast Pacific on missions unknown.

Smitty and Shineman were about to graduate from Submarine School. Once they got their orders, they would head for Mare Island, near San Francisco, and be assigned to boats.

It was 20 December 1942, a little over a year since Pearl Harbor. Much had happened during that year—both to Smitty and to the rest of the world. The worst was over, but victory remained elusive and could not yet be seen beyond the horizon.

On this night, the city of San Diego, trimmed in wan Christmas lights, hummed with the sounds of dozens of tattoo machines whirring away, accompanied by the sounds of hundreds of drunken sailors vomiting in alleys, or urinating in doorways, or picking fights with Marines or soldiers or civilians, or haggling with thousands of prostitutes. There was a war on, a great and glorious Navy war, and thousands of young soldiers, sailors, Marines, and airmen just like Ron Smith, many of them far from home, were getting drunk, getting tattooed, and getting laid—sowing their wild oats, as the phrase went—for none of them knew when they might go to sea, or if they would ever return.

SUBMARINE School at San Diego was at last concluded, but there were no ceremonies—not even a piece of paper or certificate of graduation. Because they might receive their orders at any time, Smitty and his fellow graduates were confined to the receiving station, killing time, allowed only four-hour liberties in the evenings, from 1800 to 2200 hours. Cachalot had cast off from its dock and was headed to New London, Connecticut, where it would again become a floating classroom, and freshly tattooed John Ronald Smith was nursing a sore arm. But he didn’t mind; he and the other eight graduates were waiting for their orders.

Finally, on Christmas Eve, the orders came down, and the next day, the nine Submarine School graduates found themselves on a train, heading north to Mare Island, California. After dark, the passengers were required to keep the window shades drawn. “By military order, no lights were allowed to show on the ocean side of the train,” Smitty recalled. “There were Japanese submarines operating off the West Coast and the military didn’t want them to see the train or anything it might silhouette. All of the Japanese-Americans who lived on the West Coast had been rounded up and put into camps farther inland; there wasn’t time to figure out who was a fifth columnist and who was a loyal American.”

Smitty felt that the entire West Coast was ripe for invasion. “The civilians didn’t know it but everyone in the military realized that the Japanese could have invaded us anytime they wanted. We had virtually no defense on the West Coast; they prayed that the Japanese wouldn’t find out how easy it would be.” Of course, by the end of 1942, after suffering one naval defeat after another, and forced onto the defensive far from American shores, the Japanese no longer had the strength to mount a full-scale invasion.

1The Japanese, however, did have enough resources to keep nervous West Coast inhabitants on the verge of panic. Shortly after Pearl Harbor, nine Japanese submarines had begun patrolling the U.S. Pacific coastline, seeking targets of opportunity near Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, San Diego, and elsewhere. For the next few months, a number of oil tankers and merchantmen were shot at; some were hit and some Americans lost their lives. On 23 February 1942, the Japanese submarine I-25 had fired thirteen shells at an oil refinery at Goleta, near Santa Barbara, California. On 21 June of that year, I-25, with its 5.5-inch deck gun, shelled both Fort Stevens and Fort Canby, guardians of the mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon and Washington, respectively; no injuries or serious damage were inflicted. The I-25 also carried a tiny seaplane with folding wings in a hangar built onto its deck. On 9 September 1942, the seaplane dropped incendiary bombs on Mount Emily, near Brookings, Oregon, in hopes of starting massive forest fires; the plan failed.

Also during the course of the war, the Japanese launched 9,300 incendiary “fugo” balloons from Japan that were supposed to cause great fires when they drifted across the ocean and crashed to earth in the United States. These hydrogen-filled balloons came down in Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Wyoming, Michigan, Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas, Texas, Alaska, eastern Canada, and even central Mexico. One landed near the facility at Hanford, Washington, that was involved in the top-secret operation to develop an atomic bomb, and caused a brief electrical outage. Of the 300 balloons that eventually reached the U.S. West Coast and Canada, only one caused any casualties

202The Los Angeles area was especially worried about an invasion, or at least enemy aerial attacks. The Lockheed aircraft plant in Burbank was considered a prime target, so much so that Warner Bros. studios, whose nearby soundstages looked from the air like a factory, painted a large arrow on the roof of a building and the words LOCHEED—THAT-A-WAY. (Lockheed reportedly returned the favor by painting an arrow on one of its roofs pointing in the opposite direction with the message: WARNER BROS.—THAT-A-WAY.)

Hollywood historian Harlan Lebo notes, “Most of the large film studios developed ingenious plans to camouflage their operations. Studio painters, construction crews, and nursery departments were prepared to create elaborate artistic schemes that overnight could shroud an entire complex. By combining paint, greenery, and netting, the crews could produce a clever re-creation of the natural landscape, so a studio could ‘disappear’ from view by air—practically at a moment’s notice.”

3Of course, from his train, Ron Smith was unaware of this. “We traveled first class,” he recalled, noting that the train had a luxurious feature: Pullman bunks. During the day the bunks were seats facing each other; at night the porter converted them into bunks, one up and one down. Each bunk had a curtain that could be closed and snapped shut for privacy.

The sailors found their way to the dining car, enjoyed a civilized meal, and then wandered into the club car, which was a rolling bar, to play cards. Smitty noted, “The club car was a great place to pick up women, and Jim Caddes did.” The rest of the weary gobs had retired to their Pullman bunks for the night when they were awakened by the sounds of Caddes and the girl climbing into his lower berth. Smitty had just drifted back to sleep when there came a loud thud. He poked his head through the curtains to see Bill Partin lying in the aisle, moaning.

Smitty jumped down to help his buddy and asked what had happened. “I was hanging out of my berth,” Partin told him, “trying to peek down in Caddes’s berth to watch him with the broad. His curtains were snapped tight, so I reached down to pull the snap with both hands when I lost my balance and fell.”

Everyone in the car, with the exception of Caddes, howled with laughter. “You guys think it’s funny. Well, it’s

not. She has her clothes back on and I didn’t even

finish.”

4The laughter broke out anew.

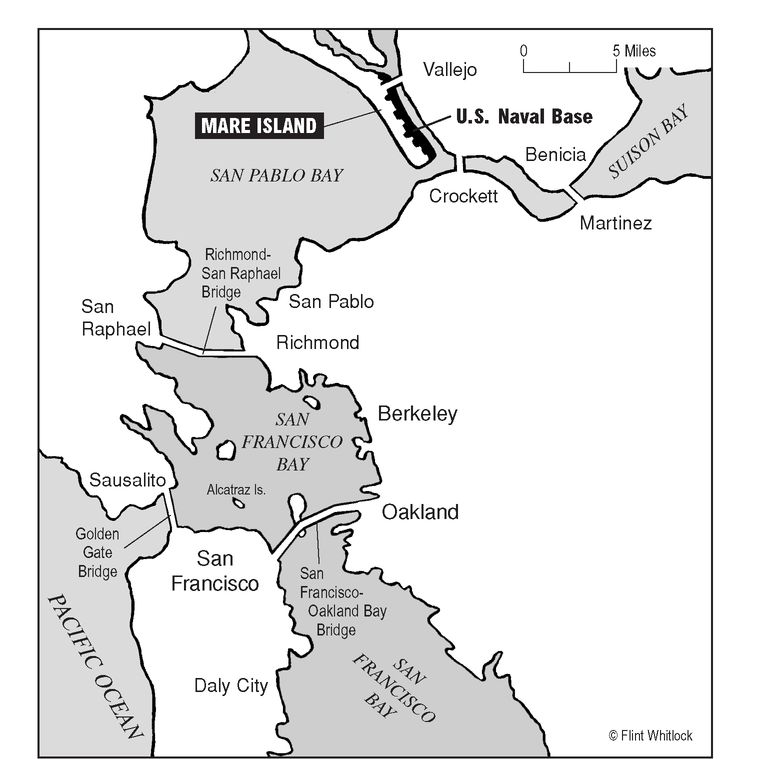

ABOUT thirty miles northeast of San Francisco, in San Pablo Bay, the Mare Island Naval Shipyard sprawled along a spit of land on the western side of the Napa River, across from the Navy town of Vallejo. It was truly a veritable beehive of wartime activity.

In 1859, Mare Island became the birthplace of the first American warship to be built on the West Coast, the frigate U.S.S. Saginaw. Houses, barracks, workshops, docks, ordnance manufacturing and storage facilities, and other buildings soon sprouted in the California sun.

In 1891, after nineteen years of construction, a second dry dock, 508 feet long, was finally completed. It took another eleven years to construct a third dry dock, this one 740 feet long. In 1919, the battleship U.S.S. California, which would be badly damaged at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 but refloated and repaired, was built and launched here. During the 1920s, Mare Island Naval Shipyard became one of the Navy’s primary facilities for the construction and maintenance of submarines, and the goal was to build one new submarine here each year for ten years.

By the late 1930s, more than $100 million had been invested in the Mare Island Naval Shipyard, the largest single industrial plant west of the Mississippi. Before the outbreak of the Second World War, some 6,000 people were employed on the base in the construction and repair of ships; after Pearl Harbor, there would be 35,000 more.

During World War II, Mare Island was a place of vital importance. By the end of the war, the facility would produce hundreds of vessels, including more than 300 landing craft, thirty-one destroyer escorts, four submarine tenders, and seventeen submarines. (As an aside, the shipyard set a record by constructing the destroyer U.S.S.

Ward [DD-139] in 1918 in just seventeen and a half days.

21)

San Francisco area, showing Mare Island Naval Base.

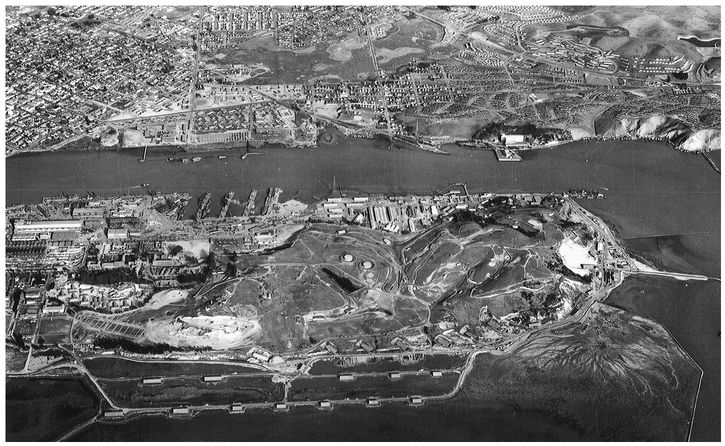

Aerial view of Mare Island Naval Base, California. The city of Vallejo is at the top of

the photo.

(Courtesy Naval Historical Society)

Detraining at Crockett, the nearest depot to Vallejo, Smitty and the other eight sailors, after unsuccessfully trying to buy beer on a Sunday, hopped on a bus that took them to the base. There they were assigned a temporary barracks while they waited for the Navy to assign them to boats. While waiting, they got paid; they had gone without pay for nearly two full paydays and were rewarded with over a hundred dollars each. Wealthier than sheikhs, Smitty and Jim Biggars took the ferry into Vallejo for a little R&R. “It was a busy little town,” Smitty recalled, “bustling with Navy yard workers and sailors. You could see the Navy yard across the small bay of water, running full blast with welding flashes spewing everywhere. It sprawled for as far as you could see in either direction.”

To Smitty, Vallejo, California, seemed to be one giant drinking establishment. On Georgia Street, both sides of the street were solid with beer joints. Not just a few bars, but dozens of bars, with names like “Porthole” and “Bloody Bucket” and “Crow’s Nest,” as if having a name with some nautical association was mandatory.

Smitty and Biggars strolled into one of the bars and ordered two beers. “The bartender never even asked to see our IDs. These people were in a different world that had its own set of rules. ‘If you’re old enough to fight, you’re old enough to drink,’ seemed to be their attitude, which was okay with me and Jim. It was a real Navy recreation area for submariners. Civilian police were nonexistent; Army MPs always came with a Shore Patrol escort if they were looking for AWOLs or deserters. The Shore Patrol was present in force. Their only weapons were nightsticks, and every sailor knew they were there to protect you.”

Smitty glanced around at the few women in the place and thought they looked “well worn.” A soused and grizzled motor machinist’s mate with silver dolphins on his sleeve came over and bought both of the lads a beer.

“I suppose you two are headed for the pig boats?” he said. Smitty hadn’t heard that term for submarines since his dad had told him about the World War I subs being dubbed “pig boats” because of their odoriferous interiors.

“Yep, we just graduated from Sub School,” Smitty told him.

“Oh, you guys just in from New London?”

“No, we went to school in San Diego.”

The older man chuckled. “Don’t try and bullshit a bullshitter. There ain’t no Sub School in Dago.”

Biggars chimed in. “They just started it. We were in the first graduating class.”

The old salt wasn’t buying it. “They ain’t got no subs in Dago,” he insisted. “They’re all here, right over there,” he said, waving in the general direction of the naval base. “This is the main sub base on the West Coast. Aw, who cares? Hey, barkeep—give these boys a couple more beers.” He slapped two quarters on the bar, then went off to make time with one of the “well-worn” female patrons. The two teenagers just looked at each and smiled.

5

THE new year did not start well for the Silent Service. Although John Pierce’s venerable

Argonaut had found a Japanese convoy bound from Lae to Rabaul on 10 January 1943 and sank one destroyer and damaged two other vessels, the enemy subjected

Argonaut to a severe depth charging that burst her forward ballast tanks and caused her to pop to the surface. Helpless,

Argonaut received murderous fire from the destroyers and she sank; Pierce and his crew of 106 were killed. It was another reminder of the dangerous world in which the submariners lived—a world that Ron Smith couldn’t wait to experience.

6

BILL Trimmer, who had survived the attack at Pearl Harbor while serving aboard the battleship Pennsylvania, and had also gone through the battles of the Coral Sea, Guadalcanal, and Midway with her, was transferred to submarines. In late 1942, he had been sent to Submarine School at New London, and the gyro and battery schools. In January 1943, he was assigned to the S-37 in San Diego. “When I first saw her,” he said, “I almost died. She was in refit, an old, small submarine commissioned in 1923. Her test depth was only 200 feet. I went below and introduced myself to Gunners Mate First Class Hurt; he was Chief of the Boat.”

Trimmer was wishing he had never left the Pennsylvania. “There wasn’t any shower aboard,” he lamented. “Only one small washbasin in the after-battery compartment, which was also the galley and mess hall. There was one small table without seats. We ate anywhere we could find a place to sit down. Most of the time we stood up and ate.”

S-37 operated with the Sub School and took students out on training runs. The submarine was then ordered to Dutch Harbor in the Aleutians, but broke down about halfway there, limping back to Hunters Point, a shipyard just outside San Francisco.

Then Trimmer caught a break: appendicitis. “Thank goodness the S-37 broke down or I would have been at sea when my appendix ruptured.” He spent twenty-six days in the base hospital; S-37 sailed without him. While he recuperated and waited for a new assignment, he became engaged long-distance to Irene Sprinkle, a girl from Orange, Virginia.

It was not until the spring of 1944 that he finally went back out to sea on a newly commissioned Fleet submarine of the

Balao class, the U. S.S.

Redfish.

7

BY the end of January 1943, American submarines were racking up impressive scores against enemy shipping.

Nautilus sank a small freighter north of Bougainville on the ninth and

Guardfish, under skipper Thomas B. Klakring, sent a patrol boat, destroyer, and cargo ship to the bottom. In the Bismarcks, Hank Bruton’s

Greenling torpedoed an ammunition freighter that went up in spectacular fashion.

Gato (William G. Myers) holed two cargo ships and

Swordfish (Albert C. “Acey” Burrows) sank another.

Growler, from her base in Brisbane, added to the total by downing a 6,000-ton passenger-cargo ship but lost her valiant commander, Howard W. Gilmore, a month later, in dramatic fashion.

8On the night of 7 February 1943, while running on the surface to charge Growler’s batteries, Gilmore, on the bridge, spotted the Hayasaki, a 900-ton armed merchantman, a mile away. Just as Gilmore ordered the sub to dive, Hayasaki charged her, blasting away with its deck gun. Shells killed two men on the sub’s bridge and wounded three others, including Gilmore. Gilmore, trying to avoid a collision, ordered left full rudder, but it was too late; the two vessels crashed into each other and the collision was so violent that eighteen feet of Growler’s bow was bent to port at a ninety-degree angle. After directing the men in the conning tower to carry the other two wounded men below, Gilmore ordered, “Take her down!” The executive officer hesitated for a few seconds; should he save the boat or the captain?

With a heavy heart, he relayed Gilmore’s final order,

Growler dove, and the skipper was washed away to his death. Amazingly, despite the severe damage,

Growler managed to make it back to Brisbane, where she was repaired by 1 May. For his courage, Gilmore was posthumously awarded the first Medal of Honor given to a submariner in World War II, and passed into Navy legend.

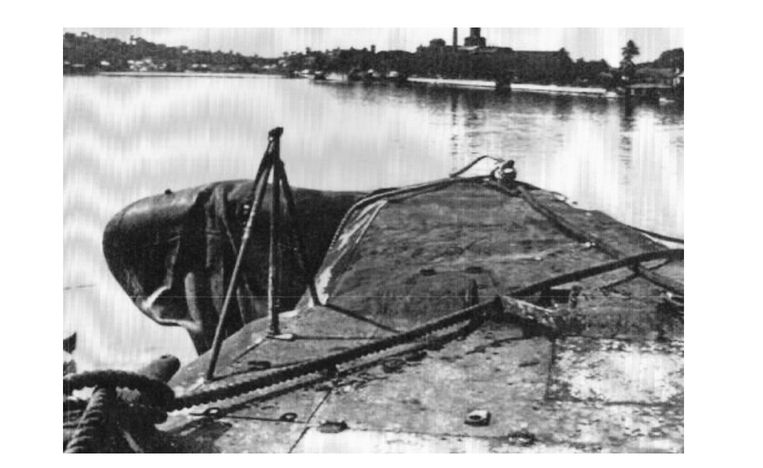

9The bent bow of Growler after her collision with an armed Japanese

freighter, photographed in Brisbane, Australia. Growler’s commander,

Howard W. Gilmore, lost his life in the incident and earned the Medal of

Honor posthumously.

(Courtesy National Archives)

THE days went by slowly, but still no orders arrived for the nine Sub School graduates at Mare Island. Smitty began to think again about putting in an application for flight training; was he ever going to get into the war? Then somebody found out that there were dollar-an-hour jobs available at the nearby Oakland Ship Yard. If the chief had no details for them after morning muster, the sailors donned dungarees, jumped on a bus, and rode into Oakland.

“They hired anyone for all sorts of menial jobs,” Smitty recalled, “like fire watches or sweepers. All you had to do as a fire watch was to stand by a welder with a fire extinguisher and put out any little fires that started.” Smitty found out quickly that the main thing you had to do at Oakland was to hide out for eight hours and then collect your money at the end of the day. Occasionally a boss would catch someone goofing off and assign him to some other detail, but for the most part, it was a screw-off deal. The money started piling up fast—forty dollars in just five days. That was almost two-thirds what Smitty and his mates were making every month in the Navy!

10

THE plane, an amphibious Pan Am Clipper on loan to the Navy, took off from the waters of Pearl Harbor and banked to the east, on a heading for San Francisco. It was 20 January 1943. On board was Admiral Robert English, ComSubPac, and three of his most-trusted staff officers: John J. Crane, William G. Myers (former skipper of Gato), and John O. R. Coll, along with a handful of other officers and the civilian flight crew. While in San Francisco, English planned to visit the submarine base at Mare Island.

As the Clipper neared the California coast, it was engulfed in a fierce winter storm and the pilot lost his bearings. The radio also failed. When communications were finally reestablished, it was discovered that the plane was 115 miles off course north of San Francisco, struggling through a stiff wind, heavy rain, and a blanketing fog. Contact was again suddenly lost—this time permanently. It was ten days before the charred and mangled wreckage of the plane was discovered in the remote, inaccessible mountains east of Ukiah; Admiral English and the other eighteen persons on board had perished instantly.

The entire Submarine Service reacted to the news as if they had been bludgeoned. While the admiral had his shortcomings and de-tractors, no one felt he deserved this ending. Much speculation arose as to who English’s successor would be. Chief of Naval Operations Admiral King ended the speculation when he appointed Charles Lockwood to the post of SubComPac; Rear Admiral Ralph Christie replaced Lockwood in Perth-Fremantle.

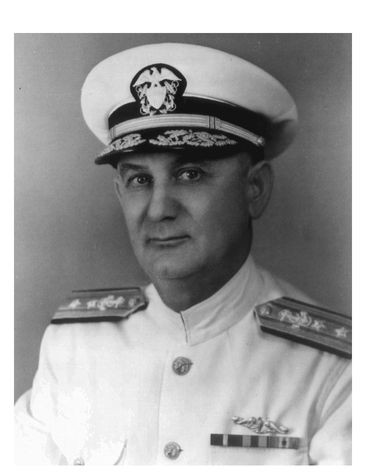

11Admiral Robert English, ComSubPac, killed in a plane crash on 20 January 1943. (Courtesy National Archives)

A new day was about to dawn for the submarine force.