CHAPTER 13

THE ROAD TO TOKYO

IN late November 1943, the scuttlebutt at the beer garden hit Smitty like a depth charge:

Sculpin had been sunk.

34 His friend Bill Partin, whose wedding he had attended in San Diego, was a crewman aboard

Sculpin. Smitty also heard that a number of men supposedly had survived and had been picked up by the Japanese; he waited anxiously to hear if Bill was among them.

The good times he had spent with Bill at San Diego came back to him. Smitty recalled the night when Partin had fallen out of the upper berth of the train from Dago to Mare while trying to get a peek at Caddes having sex with that girl he had picked up in the bar car.

Smitty remembered all the goofy, practical jokes Bill had played on him and the others, his quick wit, and his seriousness when he buckled down to study. He pictured Bill sitting across from him at the Pearl beer hall just a few weeks earlier, a thick, black beard covering his young face, showing Smitty a photo of his newborn son, all the while laughing and joking and acting like the war was a big lark, just before Sculpin sailed for the last time.

He couldn’t get the two images out of his head: that of Bill and Mary on the evening of their wedding in the Destroyer Base chapel, and how happy each of them looked that night, and the other image—the photo of the baby who would grow up never knowing his father. And now Bill was missing at sea. Smitty wondered how Mary got the news, and how she was taking it. He thought maybe he should write to her, but he didn’t have her address. And he didn’t know what he would say, what he

could say, that would make the pain any less.

It must be awfully hard on everyone who finds out that something has happened to their son or husband, he thought.

If you get killed, then you don’t have any more worries. But it’s your survivors who suffer.

1

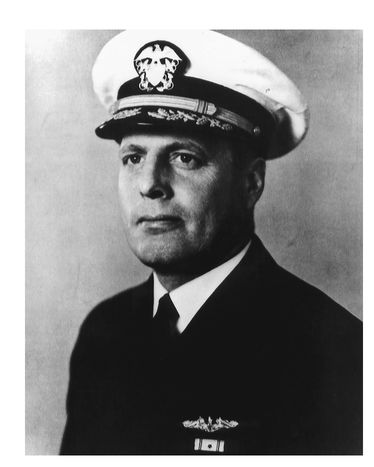

THE loss of Sculpin was one of the most dramatic chapters of the war in the Pacific, and any account of heroism among submariners would be incomplete without recounting the death of that boat, half her crew, and the self-sacrifice of Captain John Philip Cromwell, commander of a Submarine Coordinated Attack Group, who went down with the Sculpin during Operation Galvanic, the invasion of Tarawa and Makin Islands in the Gilberts.

Cromwell, born in 1901, graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1924 and served on the battleship U.S.S. Maryland before serving in several submarines between the world wars. At the beginning of the war, he was on the staff of ComSubPac, where he was in charge of Submarine Divisions 44 and 203. He was later assigned the additional command of Submarine Division 43.

In November 1943, after its successful conclusion of the Solomons campaign, the United States prepared to invade Bougainville, Tarawa, and the Makin Islands. A group of submarines

35 took up station in the Marshalls and Gilberts to counter any Japanese moves to interfere with the operations. Cromwell was a part of the Tarawa operation and he made the

Sculpin—on its ninth patrol and commanded by Fred Connaway on his first—his flagship.

Historian Edward C. Whitman notes, “Captain Cromwell possessed secret intelligence information of our submarine strategy and tactics, scheduled Fleet movements, and specific attack plans ... As a senior officer, Cromwell was completely familiar with the plans for Operation Galvanic and knew a lot more about Ultra

36—and its source—than anyone else on

Sculpin.”

2Sculpin arrived on station east of Truk on 16 November. Two nights later Sculpin’s radar picked up a large Japanese convoy steaming at high speed towfard Truk. Connaway submerged for a dawn attack, but his periscope was spotted by the enemy, who drove the Sculpin deep; by the time the sub resurfaced, the convoy was gone. An enemy destroyer, the Yamagumo, lagging behind, pounced on Sculpin, forcing Connaway to again dive and remain below for several hours. During the fearsome depth-charge attack, the sub’s depth gauge was broken; when she attempted to come to periscope depth, the diving officer, mistakenly thinking she was still 125 feet below the surface, brought her completely up, where she became a target for the lurking destroyer. More depth charges followed, which distorted the hull, sprang a number of severe leaks, and badly damaged Sculpin’s steering and diving-plane gear.

Unable to control the boat below the waves, Connaway decided that his only hope was to surface and shoot it out with the Yamagumo. It was a brave but foolhardy decision, for the submarine’s puny deck gun proved to be no match for the enemy’s heavier and more abundant armament. The destroyer’s first salvo blew apart the Sculpin’s bridge and conning tower, killing Connaway, his executive and gunnery officers, and the watch team; the deck-gun crew was also wiped out in the exchange of fire. With Sculpin in imminent danger of sinking, Lieutenant G. E. Brown, a reserve lieutenant and now the officer in charge of the boat, ordered her to be scuttled and abandoned.

Whitman notes, “This action left Captain Cromwell facing a fateful choice. With his personal knowledge of both Ultra and Galvanic, he realized immediately that to abandon ship and become a prisoner of the Japanese would create a serious danger of compromising these vital secrets . . . under the influence of drugs or torture. For this reason, he refused to leave the stricken submarine.” His last words to Lieutenant Brown were “I can’t go with you; I know too much.”

Captain John P. Cromwell chose to die

aboard Sculpin rather than risk

capture.

(Courtesy Naval Historical Center)

Whitman said, “Cromwell and eleven others [including Bill Partin] rode

Sculpin on her final plunge to the bottom, where her secrets would be safe forever.” Ensign W. M. Fielder, the diving officer whose actions had led to the

Sculpin’s erroneous surfacing, was one of those who chose death over capture.

3Lieutenant Brown, two other officers, and thirty-nine enlisted men were picked up by the Japanese; one badly wounded crewman was thrown overboard by his rescuers and drowned. To heap even more tragedy upon the situation, the aircraft carrier

Chuyo, transporting half of the

Sculpin survivors, was torpedoed and sunk by the submarine

Sailfish on 4 December 1943; only one American from this group was rescued.

37 In all, twenty-one survivors from

Sculpin finally made it to a prison camp, where they remained for the rest of the war.

When Admiral Lockwood learned after the war from

Sculpin’s survivors about Cromwell’s selfless action, he recommended the captain for the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military award for valor. Congress concurred and Cromwell’s widow was presented with the medal after the war.

4IT took a few weeks before the list of prisoners who survived Sculpin’s sinking was received and promulgated at Pearl. Bill Partin’s name was not on the list.

The not-unexpected news hit Smitty with unexpected force—almost as much as the death of his mother. At least with his mother, her long illness had braced him and the rest of the family for the inevitability of her passing; and while submariners knew that they could die at any moment while at sea, the reality of Bill’s death—the finality of it—struck home with a staggering blow. He’s so young, Smitty thought, maybe only a year older than me. How could this have happened? Smitty found a private place and shed a tear for his lost friend—and for everyone who had thus far made the ultimate sacrifice.

Once he had pulled himself together, Smitty went to Captain Blair and confided to him about the loss of Sculpin and Bill’s death. Blair seemed callous and unconcerned. “War is hell, son,” is all the senior officer said, then went back to reading a report. At that moment Smitty had to restrain himself from leaping over the captain’s desk and attacking him. “Don’t you give a shit?” Smitty wanted to scream. “Don’t you care that people like Bill Partin are dying in this goddamn war while your fat ass is nice and safe here in your goddamn leather-covered chair?”

While he was attempting to rein in his emotions, it suddenly became obvious to Smitty that he could no longer continue living the soft, safe life at Pearl while his friends were putting their lives on the line every minute of every day. What makes me think I’m so special that I get to sit out the war like Blair in beautiful Hawaii? he asked himself. I joined the Navy so I could fight the Japs, so what the hell am I doing here, not fighting the Japs?

A great surge of anger was welling up in him—an anger at Blair’s uncaring response, an anger at himself for taking the easy way out, and an even more white-hot anger at the Japanese who had caused the war and caused Bill’s death. “You can’t do that to my buddy,” a voice in his throbbing head wanted to yell out loud enough that it would be heard across the ocean, all the way to Tokyo. “It has nothing to do with patriotism or flag-waving or being a loyal American or wanting to win a medal. It has to do with loyalty to my buddy. Well, listen up, Tojo. I’m coming back and I’m going to kill every last one of you sons of bitches, even if I have to die in the process!”

Stiffening to attention, Smitty said to the unconcerned captain, “Sir, I request that my pending appointment to the Naval Academy Prep School be withdrawn. I’d like to go back to submarines.”

Blair didn’t even look up. “Request granted,” he said, almost as though he had been expecting this for a long time. Then he verbally slapped Smitty with the remark, “I’m not sure you’re officer material, anyhow, Smith.”

Smitty saluted briskly, performed a perfect about-face, and marched out of the office. He was certain that, had the captain looked up, he could have seen smoke coming out his ears.

5

OPERATION Galvanic—the invasion of Tarawa Atoll, consisting of thirty-eight small islands, principally Betio and Makin—began the day after Sculpin’s sinking—20 November 1943. Because of his superb performance during the fight for Midway a year and a half earlier, Nimitz installed Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance to command Galvanic.

Tarawa was another of the many Pacific land battles that brought new meaning to the word savagery. Ever since the fall of Guadalcanal, Imperial Japanese Marines and Korean slave laborers under the island’s principal commander, Rear Admiral Keiji Shibasaki, had been engaged in building an airfield on Betio and fortifying the atolls in anticipation of an American attack. And now that time had come. Emplacing four of the heavy coastal artillery pieces captured from the British at Singapore, Shibasaki planned to blow any invasion fleet out of the water, boasting that “a million men could not take Tarawa in a hundred years.”

The actual landings on Makin Island were relatively easy. Six thousand Marines came ashore, opposed by 300 Japanese troops and 500 Korean workers who had been forced at gunpoint to fight. During the brief engagement, all of Makin’s defending soldiers were wiped out, plus half of the Koreans; the rest surrendered. Sixty-four Americans died.

6But Betio proved to be a tougher nut to crack. Following a three-hour saturation bombardment by three battleships, five cruisers, and nine destroyers in the early morning hours of 20 November, the 2nd Marine Division was ready to come ashore on Betio’s lagoon side. A greeting party of some 4,800 battle-hardened Imperial Japanese Navy Marines, augmented by 2,300 armed Korean and Japanese laborers, was lying in wait for them. The laborers had done a masterful job of turning Betio into a deadly fortress made of reinforced concrete pillboxes covered with coconut logs, from which the defenders could pour an intense concentration of artillery, mortar, and machine-gun fire at the invaders.

Marines battle for Tarawa.

(Courtesy National Archives)

Compounding the difficulties was the fact that someone on the American side had screwed up royally and gotten the tides wrong. The six transports, crammed to the gunwales with Marines, were sitting ducks for the Japanese shore batteries. As if that weren’t enough, the naval bombardment ended early and the carrier pilots were late. “The thirty-minute airstrike,” Manchester says, “lasted seven.” When at last the Marines climbed down into the Higgins boats—plywood landing craft whose flat steel bows could be dropped to let the troops out into shallow water—they got hung up on the coral reef at low tide, forcing the troops to wade in for over a mile, where they were raked by enfilading fire.

With nowhere to take cover, the wading Marines, trudging toward shore as if in the slow motion of a bad dream, were easy targets for the Japanese gunners. Although the first wave of Americans was nearly totally destroyed, more Marines came on, delivered into the killing zone by Higgins boats and “amphtracs”—armored amphibious vehicles that held twenty men. Somehow, they got to the beach.

William Manchester observes, “The Marine dead became part of the terrain; they altered tactics; they provided defilade, and when they had died on barbed-wire obstacles, live men could avoid the wire by crawling over them. Even so, the living were always in some Jap’s sights . . . As the day wore on, the water offshore was a grotesque mass of severed heads, limbs, and torsos.”

Men were paralyzed by the sight of so much death and destruction, and by the wholesale slaughter of their officers and noncoms. Movement forward seemed as impossible as leaping up and touching the moon. Somehow, someway, though, small bunches of frightened men summoned up courage they did not know they possessed, said “Let’s go” to their equally frightened buddies lying next to them, and crawled across the blood-soaked sand to engage the entrenched enemy with rifles, pistols, grenades, flamethrowers, bayonets, knives, bare hands.

The enemy fought with unbelievable tenacity, a characteristic that prompted Manchester to write, “At the time it was impolitic to pay the slightest tribute to the enemy, and Nip determination, their refusal to say die, was commonly attributed to ‘fanaticism.’ In retrospect it is indistinguishable from heroism. To call it anything less cheapens the victory, for American valor was necessary to defeat it.”

7The battle offshore was equally savage. The carrier

Liscome Bay was torpedoed by a Japanese submarine and 644 sailors died.

8It didn’t take a million men a hundred years to overcome the nightmare of Tarawa. It did, however, take 35,000 American fighting men three days to utterly wipe out the defenders; only seventeen Japanese or Koreans were taken prisoner. Shibasaki and his staff committed suicide. Fifteen hundred Americans died during the battle. It was a terrible toll compressed into just seventy-two hours. But America was another island group closer to Japan—and victory.

9

LOCKWOOD’S submarines had done a creditable job during November. Although the bugs in the Mark XVIII electric torpedoes had yet to be worked out, the crews were doing yeoman’s service with the revamped Mark XIVs. During the month, three enemy warships and forty-eight merchant vessels—displacing a total of 232,333 tons—went to the bottom, sent there by American subs.

10

SEAL’S ninth war patrol turned out to be an easy reconnaissance mission to the Marshall Islands in preparation for the upcoming Operation Flintlock—the offensive against the Marshalls and Truk Island. Between 17 November and 15 December, Seal scouted the proposed invasion beaches and photographed through her periscope the visible Japanese defenses on fifty-six of the ninety-six islands that make up the chain. After refit at Midway, Seal proceeded to Pearl for dry-docking to replace a malfunctioning screw.

Smitty went down to the Ten-Ten Dock a week before Christmas 1943 to greet his shipmates as Seal returned from her patrol with no new additions to her battle flag. Approaching Chief Weist as he was coming off the boat, Smitty said, “How’d it go, Chief?”

“Don’t ask, Smitty,” Weist said. “A big fat zero. We made one torpedo attack but didn’t hit anything. And later, when we made a routine dive, some asshole left the conning-tower hatch open. Nobody checked the Christmas tree, otherwise they’da seen the red light. Water poured in and shorted out most of the electrical equipment, including the air compressors, the air-conditioning motors, the gyrocompass, the pumps, the blowers, you name it. We had to repair the compressors at sea using a jury-rigged system just so’s we could operate the boat and fire the torpedoes.”

“Chief, I want back on Seal,” Smitty blurted out.

Weist gave him a wry smile. “What’s the matter—shore duty too rough for you?”

“Yeah, sitting on my ass all day, getting drunk and getting laid, has worn me out.”

“Well, I think maybe I can get you back on Seal. Your replacement turned out to be a screwup, anyway. I’ll talk to the old man and see what I can do.”

“Thanks, Chief.”

Weist was as good as his word. Following her refit,

Seal was ready once more for combat and, with Smitty back on board in the aft torpedo room, sailed on her tenth war patrol on 17 January 1944. Her mission this time was twofold: to gather information about conditions in the Ponape Island area of the Marianas, near Guam, Wake, Saipan, and Tinian, or about 1,000 miles south of Japan, and to act as a lifeguard and pick up any aircrew members who might be shot down during Operation Flintlock.

11

AS 1943 came to a close, American air forces began making concerted attacks on the enemy’s strongly defended air and naval bases at Rabaul. Although the Japanese were prepared to make another fight to the death, the Americans decided merely to isolate Rabaul and let it “wither on the vine.” In December, too, American Army and Marine units launched the invasion of Cape Gloucester, New Britain, with the purpose of taking airfields away from the enemy; so difficult was the terrain, climate, and enemy resistance, though, the job would not be finished until April.

Nineteen forty-four in the Pacific began much like 1943 had ended—with steady American gains in territory paid for by steadily rising American losses in men and matériel.

Sixteen American submarines had been lost during 1943—up from just a half dozen the previous year—but Lockwood’s force had reported sinking 422 enemy vessels during that twelve-month period.

38The United States was gearing up to push deeper into Japanese-held territory. On New Year’s Day 1944, aircraft from Rear Admiral Frederick C. “Ted” Sherman’s carrier task group bombed a Japanese convoy escorted by cruisers and destroyers off Kavieng, New Ireland; the next day U.S. Army troops landed at Saidor, New Guinea. On 8 January, Task Force 38, under Rear Admiral Walden L. “Pug” Ainsworth, bombarded Japanese shore installations on Faisi, Poporand, and the Short-land Islands in the Solomons. Three days later, Navy aircraft based in the Gilbert and Ellice Islands bombed Japanese shipping and installations at Kwajalein in the Marshalls in preparation for invasion.

12 On 14 January, the Japanese destroyer

Sazanami was sunk by the submarine U.S.S.

Albacore in the Central Pacific. The new year was off to a good start for the Americans.

13

HALF a world away, important developments were also taking place in the moribund Italian campaign. In mid-January, the Allies launched the first of the four attacks it would take to dislodge the Germans from atop Monte Cassino. On the twenty-second, in an attempt to break the stalemate, a combined U.S.-British amphibious force landed at the Anzio-Nettuno coast of Italy in Operation Shingle. It would soon get bogged down and Rome would not be taken for more than four months. Five days after Shingle began, the 880-day German siege of Leningrad was finally broken.

14Back in the Pacific, the American submarine force continued to make important contributions to victory.

Tinosa landed personnel and supplies in northeast Borneo while

Bowfin laid mines off the southeastern Borneo coast; Smitty’s previous boat,

Skipjack, sank the Japanese destroyer

Suzukaze in the Carolines.

15Following the capture of Makin and Tarawa in the Gilberts, the Americans aimed for the Marshall Islands, 700 miles to the northwest of the Gilberts. Prior to the First World War, the Marshalls had belonged to the Germans; after Germany was stripped of her Pacific colonies following the war, Japan was given the mandate by the treaty makers at Versailles to rule them—hence their other name: the “Eastern Mandates.” Now the Americans—Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner’s 5th Amphibious Force and Major General Holland M. “Howlin’ Mad” Smith’s V Amphibious Corps—under the overall command of Vice Admiral Raymond Spruance, were set to revoke the mandate.

The Japanese had greatly reinforced the Marshalls to make any at-tempt at retaking them expensive for the United States; it would prove to be a waste of effort on the part of the Japanese. Although Admiral Masashi Kobayashi, the regional commander, had 28,000 troops to defend the Marshalls, he had only 110 aircraft there—a shortage that would cost him dearly. On 29 January, American carrier planes attacked the enemy airfield on Roi-Namur, destroying ninety-two enemy aircraft in the opening moves of Operation Flintlock.

Marshall and Gilbert Islands.

Expecting the Americans to attack the outermost islands first, Kobayashi had entrenched most of his defenders on Wotje, Mille, Maloelap, and Jaluit Atolls. The Americans learned of this deployment through Ultra decryptions of Japanese communications, and thus Nimitz decided to bypass these outposts and strike directly at Kwajalein.

Kwajalein Island is less than three miles long and only about half a mile wide. For such a small space it was to be the scene of concentrated death. Learning from their many mistakes at Tarawa, the Americans pulled off the Kwajalein operation with almost textbook precision. On 31 January 1944, with complete mastery of the air and sea, the landing units—the U.S. Army’s 7th Infantry Division and the Marines’ 4th Marine Division—stormed ashore on Kwajalein and Majro Atolls, swamping the 5,000 enemy troops dug in there.

The landings were superbly supported by carrier-based aircraft and land-based aircraft from the Gilberts. On the north side of the atoll, the Marines captured a number of small islets. The airfield on Roi was taken quickly, and Namur was overwhelmed the next day. Only fifty-one of the original 3,500 Japanese defenders of Roi-Namur survived to be taken prisoner. The worst setback came when a Marine demolition team threw a high-explosive satchel charge into a Japanese bunker that turned out to be full of torpedo warheads. The resulting explosion killed twenty Marines and wounded dozens more.

By 1 February 1944, the second day of operations on Kwajalein, it was clear that the Japanese were doomed; the Americans estimated that almost all of the original 5,000 defenders on Kwajalein were dead. By 3 February, only a handful were left, and it was all over except for the burying of the bloated dead.

16

MEANWHILE, Seal’s problematic H.O.R. engines were nearly worn out, and it was time to replace them with new Fairbanks-Morse diesels—an overhaul that would require a trip back to Mare Island.

Although the majority of the crew was excited about a return to the States, Smitty was not. “There really wasn’t anything waiting for me back there. Shirley had written to tell me that she was engaged to a sailor, so I had no ‘love interest’ back home to worry about. Besides, I still hadn’t avenged the death of Bill Partin. We hadn’t sunk any Jap ships on Seal’s last three patrols. I began to think about transferring to some other boat.”

One day while downing a cold one at the Pearl Harbor beer garden, Smitty ran into an old buddy, Eugene “Jeep” Peña, the sailor who still bore burn marks on his forearm from the time he had fired a machine gun at the Japanese planes at Tjilatjap before Smitty joined Seal’s crew. Peña now wore the insignia of a chief petty officer.

“Hey, Jeep, what’re you doing here?” Smitty asked, surprised.

“Just came in with the Robalo.” Peña then gave Smitty a brief rundown on Robalo (SS-273). She was a Gato-class boat built at Manitowoc, Wisconsin, and had been floated down the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico, then through the Panama Canal and over to Pearl Harbor, where she was put into commission.

“No shit? That’s great! And I see you’re chief of the boat, too?”

“Yep. I got transferred off Seal to join Robalo. Hey, what the hell are you doing these days?”

Smitty gave Peña an abbreviated version of his life. The chief then said, “Smitty, I got a real problem. Less than a third of the crew is qualified. I gotta find me some guys who know their shit. Guys like you.”

“Yeah? Sounds interesting.”

“Our boat has all the latest gadgets,” Peña offered. “We got power-operated doors on the tubes now. Even the air-conditioning works! Besides, you’ll really like our skipper. He’s Admiral Kimmel’s son.”

“No shit?” Smitty was intrigued. In the official congressional inquiry that followed the Pearl Harbor debacle, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel was blamed for letting the Navy’s guard down and allowing the Japanese to raid Pearl Harbor. Surely the bad luck that dogged the admiral wouldn’t follow his son.

“Listen, I’ll get you torpedoman first class and put you in charge of the after torpedo room. What do you say?”

“Well—okay. You talked me into it.”

“C’mon, let’s go down to the dock and look her over.”

The two submariners finished their beers and strolled over to where Robalo was tied up. She looked fresh and new, not war weary like Seal. A big “273” was welded onto her conning tower.

The two men crossed the gangway, saluted the colors, and requested permission to come aboard. As he slipped down through the hatch, Smitty’s eyes grew big. Brightly polished brass and chrome gleamed everywhere, like burnished gold and silver in a sultan’s treasure room. The bulkheads were wood-grained, giving Robalo an almost yachtlike appearance. She even smelled new; her decks and bulkheads were not yet permeated with the stench of sailor sweat.

Smitty was amazed that the new generation of

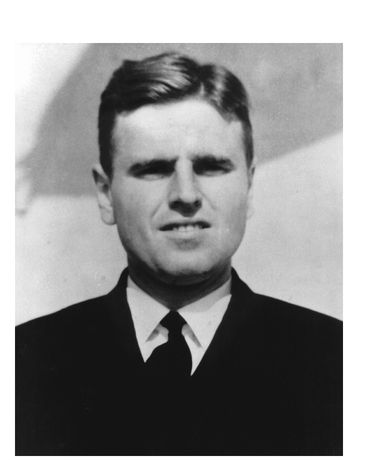

Gato-class submarines had outclassed the old boats to such a degree. Then Jeep took him to meet the skipper, Lieutenant Commander Manning M. Kimmel, class of 1935.

17Although only thirty years of age, Manning Marius Kimmel was already an old salt in submarines. From 1935 to 1938, he had served aboard the battleship

Mississippi, then attended Submarine School at Groton. His first submarine assignment was aboard the ancient

S-38 before he transferred and helped put

Drum into commission in early 1942; he served on

Drum during her first three war patrols. He became part of the precommissioning crew of

Raton (SS-270) and was her executive officer after her commissioning in July 1943. After two war patrols with

Raton, Kimmel was given command of

Robalo, still undergoing construction at the Manitowoc shipyard.

18Smitty was impressed with Kimmel and the feeling was apparently mutual; the officer invited Smitty to transfer off Seal and join his crew. All that was needed was the approval of the officer for whom Smitty had been the chauffeur.

But, the next day, Blair turned down Kimmel’s request, saying that Seal had the right of first refusal for Smith’s services. If they did not want him back, then Kimmel could have him. Smitty glared at the captain. “If looks were punishable,” he said, “I would have gotten ten years.”

Manning Marius Kimmel, skipper of Robalo. (Courtesy National Archives)

A large crowd watches U.S.S. Robalo being launched at the Manitowoc

Shipyard in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, 9 May 1943.

(Courtesy National Archives)

“Sorry, Smith,” said Kimmel after they had left Blair’s office. “I would have liked for you to have been part of our crew. Maybe someday.”

“Yes, sir. Maybe someday.” Smitty saluted and the two men parted.

19 Neither one could know that, on 26 July 1944,

Robalo, Manning Kimmel, and fifty-five others on board would die when the boat struck a mine off Palawan, west of the Philippines. For some unknown but fortunate reason, Jeep Peña would be transferred off

Robalo before the sinking. Four men would manage to escape the stricken boat, swim to shore, and be taken captive by the Japanese. Their fate remains unknown to this day.

20WHILE waiting for Seal to leave Pearl for California, Smitty was rousted out of his bunk in the relief-crew barracks by Deason, the chief torpedoman of the submarine base. The chief said he had a big problem—one of Salmon’s torpedoes had been accidentally fired while the boat was moored and the fish was jammed partway out of the tube. Smitty got dressed hurriedly and grabbed his swim trunks.

As they rushed to the dock, Deason went into detail: One of the torpedomen had gone into the caboose to show some new men how to fire a torpedo. For some reason the interlocks that keep the torpedo from firing when the outer door is closed were unlocked. “We’re not sure how it happened,” Deason said, “but the damn thing fired—rammed the torpedo right through the outer door and wedged itself between the outer door and the superstructure door. It’s a real mess. Fortunately the fish didn’t arm itself.”

“That’s a relief.”

“We’re moving a barge into place for you so you can work on her.”

“Why me?”

“ ’Cause you’re qualified on Seal. She’s a sister ship to Salmon, same identical boat, same class.”

Smitty couldn’t disagree with Deason’s logic. “Okay, but I’ll need some help.”

“You name it.”

“How about Ferry and Lewis? They’re on the relief crew, too, and they’re qualified torpedomen.”

“I’ll get them right now,” Deason said, peeling off and heading back to the barracks while Smitty continued on to Salmon. She was down a little at the stern, and a raftlike barge with floodlights was lashed to her. A number of sailors were milling around the scene.

Smitty surveyed the situation, then slid down the hull to the raft. Slipping a waterproof flashlight into his belt, he removed his shirt and shoes and dove into the water, swimming up into the space between the hull and the plates that made up the outer superstructure. Holding his breath, he clicked on his light and ducked beneath the water. What he saw didn’t look good. The big warhead was protruding halfway out of the heavy brass, partially opened torpedo tube door and wedged up against the door built into the superstructure; the warhead had a couple of good-size dents in it. The exploder mechanism looked okay, but Smitty couldn’t tell if there was any additional damage to the warhead.

Smitty surfaced and pulled himself up onto the small barge. Warren Lewis and Jack Ferry were there by then. He told them what he had seen and got everyone’s opinion as to how best to solve the problem. Working in a very tight space, they would first have to turn the torpedo enough to be able to get at the exploder and remove it. Assuming they could do that, they next had to remove all the bolts to detach the 600-pound warhead from the air flask. Finally, the warhead would have to be lifted out with a crane.

“Okay, let’s get to work,” Smitty said, and his two helpers jumped into the water to begin the process. Somehow, the three of them managed to turn the 3,000-pound torpedo enough to give them access to the exploder. Deason had chased all nonessential personnel from the area—not because there was any danger of the warhead detonating, but the air flask, with its charge of high-pressure air at 2,000 pounds per square inch, certainly could. It took all night with the men working with the care of brain surgeons to remove the exploder.

The next day the trio took off the bent hinges and bolts from the outer door and removed it; the hinge pin alone weighed nearly 150 pounds. Always there was the danger of one of the heavy parts slipping and crushing somebody’s arm or leg, so the men worked with extreme caution, not rushing any aspect of the operation.

After working for seventy-five hours straight, breaking only for sandwiches, Smitty, Ferry, and Lewis finally removed the superstructure door. Attaching it to the big hook dangling by a steel cable from the crane, Smitty gave the signal to haul away, but the 800-pound door lurched outward and then back, straight for him. Only his quick reflexes kept him from being squashed; the door banged against the pressure hull, leaving a deep gouge in the steel.

Finally, the three sailors pushed the half-protruding torpedo back into its tube and their job was done; the rest would have to be repaired in dry dock.

Treating themselves afterward to a few drinks at the beer garden, Smitty, Ferry, and Lewis heard that three submarines—

Wahoo,

S-44, and

Dorado—were overdue.

39 “Gentlemen, we are certainly in a hazardous business,” Smitty said as he lifted his glass in salute to the 212 missing men.

Word was passed that the hospital ship U.S.S. Mercy would be arriving at Pearl Harbor that evening loaded with hundreds of Marines wounded in the savage fighting for Tarawa. Smitty went down to the dock where Mercy was moored and was struck by the enormity of the casualties—an unending procession of stretchers being carried down the gangways. “The gray Navy Packard ambulances were lined up as far as you could see,” Smitty said. “As soon as one was loaded, it took off for the hospital and another one moved up.”

At around midnight, a black Packard limousine drove onto the dock next to the hospital ship and out stepped a slim, somber-faced, white-haired officer, Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific. Smitty recalled, “He went back and forth to each gangway, talking to the wounded men on the stretchers as they were brought down. At one point the admiral was just a few feet in front of me and I could see the moisture in his eyes. I could also feel the respect and admiration the wounded men had for him. He was a real human being.”

The next day a troopship full of Marines from Kwajalein entered Pearl Harbor and the word was the Marines were willing to trade war souvenirs for cigarettes. Smitty and his friend Lewis bought armloads of cartons, went down to the dock, and began tossing them up to the Marines on the ship. Smitty didn’t want any souvenirs; he was just glad to be a “good Samaritan” and provide free smokes. But a grateful Marine threw down what looked like a dirty and stained rolled-up Japanese flag that landed with a thump at Smitty’s feet.

Smitty unrolled it and out fell a soggy mass of hair and blood. The stench was overwhelming; Smitty kicked the gruesome bundle into the harbor, not wanting to know if it was a pair of bloody Japanese ears, a scalp, or part of a head.

What in God’s name are we coming to? he wondered as he walked away in disgust.

21

DESPITE the improvements in the new submarines, life for men in the Silent Service had not grown easier or less dangerous, and courageous captains and crews were still needed to man the boats. In late June, early July 1944, immediately after the Battle of the Philippine Sea, Admiral Lockwood had formed four multiple-boat “wolfpacks” and sent them into the Luzon Strait, which was teeming with targets. One of the packs, consisting of three submarines—Slade Cutter’s

Seahorse (SS-304), An-ton R. Gallaher’s

Bang (SS-385) and the repaired

Growler,

40 under Thomas B. Oakley Jr.—enjoyed especially fine hunting. The trio reported a total of six ships sunk and several more damaged; the other three wolfpacks also scored well, sinking twelve ships during the same period.

22Slade Cutter, skipper of Seahorse, and

recipient of four Navy Crosses.

(Courtesy National Archives)

Midshipman Slade Deville Cutter had won the bitterest rivalry in college sports when his field goal defeated Army, 3-0, in the 1934 Army-Navy game. Once war broke out, Cutter—described by Lockwood as his “pride and joy”—went on to even bigger victories. In command of Seahorse, Cutter had already been awarded three Navy Crosses “for extraordinary heroism.”

Now, in July 1944, after penetrating heavy and unusually alert escort screens in enemy-controlled waters near the Philippines, Cutter launched a series of torpedo attacks and sank six enemy ships totaling 37,000 tons, while damaging an additional ship of 4,000 tons. Avoiding the enemy’s best effort to depth-charge him into oblivion, Cutter brought Seahorse safely back to port. For this courageous patrol, he received his fourth Navy Cross.

July 1944 was shaping up to be an excellent month for American submariners. On the eighteenth, Guardfish surfaced inside an immense convoy in the Luzon Strait—the largest convoy that skipper Norvell G. “Bub” Ward had ever seen. He radioed Dave Whelchel’s Steelhead (SS- 280) and Red Ramage in Parche (SS-384) and invited them to come over and share in sinking the flotilla. On 30 July, dodging Japanese planes, Steelhead and Parche moved in for the kill. Steelhead fired her ready tubes then withdrew to reload while Parche took up the attack under cover of darkness.

Lawson P. “Red” Ramage (photo taken

in 1967), skipper of Parche and

recipient of the Medal of Honor.

(Courtesy Naval Historical Center)

As Clay Blair describes it, “The next forty-eight minutes were among the wildest of the submarine war. Ramage cleared the bridge of all personnel except himself and steamed right into the convoy on the surface, maneuvering among the ships and firing nineteen torpedoes. Japanese ships fired back with deck guns and tried to ram. With consummate seamanship and coolness under fire, Ramage dodged and twisted, returning torpedo fire for gun fire . . . The attack mounted on the convoy by Red Ramage was the talk of the submarine force. In terms of close-in, furious torpedo shooting, there had never been anything like it.”

Whelchel, his tubes now reloaded, came charging back into the fray until enemy fire got too hot and both subs were forced to submerge and withdraw.

For his bold actions during that encounter, redheaded “Red” Ramage earned the Submarine Force’s third Medal of Honor.

23