CHAPTER 18

DISASTER AT SEA

DURING the Battle of Leyte Gulf, Dick O’Kane’s Tang was on station some 600 miles north of Leyte. It was Tang’s fifth war patrol, this one in the Formosa Strait, between the island of Formosa (today known as Taiwan) and Foo Chow, China. No one could know that it would also be her last patrol.

“We used to hate to patrol there because it was so shallow,” Clay Decker said. “There are a couple of places where it is shallower than 200 feet. We weren’t that fearful of a depth charge going off above us or to the side of us, but if it went off

below us, it would blow the water out of our ballast tanks. If that happened, it would give us positive buoyancy and we’d pop to the surface like a cork. We’d be sitting ducks for whoever was up there gunning for us.”

1Tang had been on station in the Formosa Strait for about a week and a half. At 0200 hours on Tuesday, 25 October 1944, while running on the surface to recharge her batteries, the blips on Tang’s radar screen blossomed into a huge convoy of thirty-five ships approaching through the strait. The radar operator could hardly believe his eyes and called the exec Frazee over to double-check that his vision was accurate.

O’Kane was awakened and informed of the sighting. Excited, he threw a bathrobe over his shorts and headed for the control room to confirm the contact for himself. It was true. The blips on the radar screen looked like a large covey of bright green quail taking flight.

2Aaaaooogaa! Aaaaooogaa! Everyone was sent rushing to his battle station as O’Kane dived and set the sub on a course to intercept the convoy. Decker recalled, “Our troops had landed on Leyte and we assumed that this convoy was heading there to resupply and reinforce the enemy. Skipper ordered flank speed, and we took off to make an end run and get in front of the convoy.”

As Tang reached the interception point and submerged to wait for the targets to come into range, O’Kane noticed that the convoy was coming on in single file without the usual zigzagging. “It was just like a shooting gallery for us,” said Decker, who was manning the bow planes and could hear and see all the activity in the control room.

O’Kane kept his eye glued to the periscope. As the sky gradually lightened, he saw the ships moving quickly, black smoke billowing from their stacks. It was an embarrassment of riches—there were so many targets it was difficult to decide which to shoot at first.

Decker recalled, “There was one troop transport among all those thirty-five ships. There were also a goodly number of destroyers, and destroyer escorts, which we didn’t like, because those were the guys with the depth charges.” But everyone was excited at the prospect of another engagement.

Tang had already sunk eighteen ships on her first four patrols; how many more could be added to that score this morning?

3As the first big target came within range and centered itself in the periscope, O’Kane went through the familiar litany of submarine commander in action. The command “bearing—mark” was Frazee’s cue to check the azimuth reading on a brass ring that circled the base of the periscope. Frazee called out the bearing: “Zero one zero.”

Next O’Kane requested the range; the radar operator sang out the yardage from the sub to the target: “One thousand yards and closing.”

“Open outer doors,” directed the skipper and the order was conveyed to the forward torpedo room, which immediately complied. A couple more range and bearing checks took place before O’Kane shouted, “Fire one!”

The first fish was launched. Seconds went by, then a heavy thump. The enemy ship went up in a giant chrysanthemum of flame and smoke, sending debris and sailors flying into the predawn sky. The destroyers, the watchdogs of the convoy, immediately went on the prowl, rushing madly about, eager to sink their blunt, 242-pound teeth into their unseen adversary.

“Fire two! Fire three! Fire four!” O’Kane commanded without removing his eye from the periscope’s rubber eyepiece. With each command

Tang lurched. Soon the shock of torpedoes leaving the sub became indistinguishable from the shock waves of exploding torpedoes detonating against Japanese hulls and the shock waves of bursting boilers inside those hulls.

4Clay Decker, being buffeted at his battle station, could only imagine what the scene on top was like—crumpled ships on fire slipping beneath the waves, men jumping overboard to escape the flames and detonations, oil burning on the water, sheer panic, death and destruction being heaped upon the hated enemy. The mood inside Tang was one of grim celebration. Tang was paying back the Japanese for Pearl Harbor, Cavite, Bataan, and a hundred other places.

The destroyers dashed about in great confusion, unable to locate Tang as one ship after another exploded in a display of submarine marksmanship seldom, if ever, equaled. The thirteenth ship sunk by Tang was the lone transport, which Decker said O’Kane estimated as holding at least 5,000 troops.

Decker said, “When the fire-control party looked at a silhouette in the book of all the enemy’s ships, they could determine the type of ship and how much water it drew. If we’d have hit a target at, say, water level, all we’d have done is blow a hole in it. They have watertight compartments and they’d seal off that compartment and stay afloat. But if you hit him just above the keel, you’d break his back and sink him. So they set the depth they wanted into the memory of the torpedo, somewhere from a foot to two feet above the keel.

“We had hit the transport in the stern with our twenty-second torpedo and stopped its propulsion, but didn’t sink it,” Decker continued. “With two torpedoes left, numbers twenty-three and twenty-four, both in the forward tubes, we approached that crippled transport. I’m sitting at the bow-plane wheel just below the hatch that goes up to the conning tower; there’s a fire-control party up there and the skipper is now up there, too, on the bridge, giving all the orders. I can hear everything that’s going on over the intercom; it was like listening to a football game on the radio.”

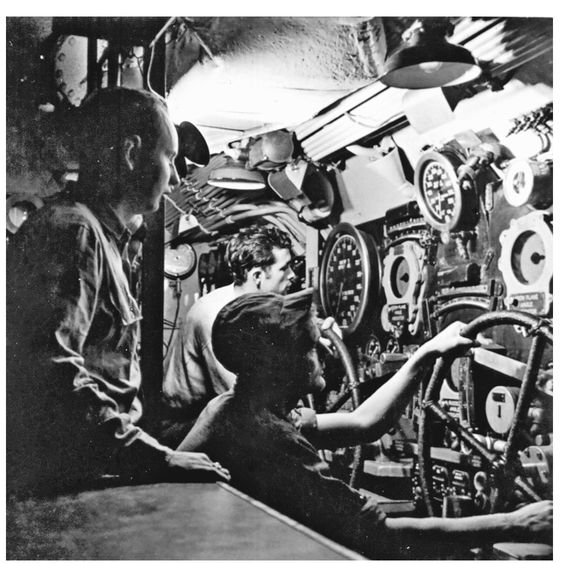

Two planesmen operate the wheels that control the angle of

ascent and descent under the watchful eye of the diving officer.

(Courtesy National Archives)

Usually, Decker said, they would fire their torpedoes at a range of a thousand to fifteen hundred yards. “Well, this time we went in on that target at a range of 700 yards. Skipper gave the command ‘All stop.’ Normally we would have one or two knots on the screws, but now we were all stopped. The reason for him doing this was,

Tang was like a big-game rifle and he’s got two shells left and there’s a big bull elk out there. The transport is sitting dead in the water, and the skipper didn’t want to miss. So we aimed the boat at the transport and fired those last two torpedoes. Number twenty-three went out straight and hot and hit the target amidships.”

5For insurance, the twenty-fourth and last torpedo was fired. Torpedoman Third Class Pete Narowanski, in the forward torpedo room, remembered that he had just pressed the firing plunger and called out, “Hot dog! Course zero nine zero—head her for the Golden Gate!”

6But something went terribly wrong. Instead of running below the surface straight for the target, number twenty-four began broaching as it ran, then circled to its left.

Seeing the torpedo coming back toward Tang, O’Kane, on the bridge, yelled an order for “all ahead emergency” and a “right full rudder” in a desperate bid to get Tang out of the way of her own errant missile.

The command came too late to get Tang moving again. Roaring in at forty-six knots, the out-of-control fish struck the submarine’s port side just ahead of the after torpedo room. The blast from the 500-pound warhead was terrific and immediately flooded the three aft compartments, together with number six and seven ballast tanks.

O’Kane found himself blown off the bridge and into the water along with the two other lookouts, the soundman Floyd Caverly and Boatswain’s Mate First Class Bill Leibold.

7Jesse DaSilva, a motor machinist’s mate second class in Tang’s after engine room, had left his station a few minutes before the blast to get a cup of coffee in the crew’s mess. “I never really liked coffee,” said DaSilva, “but that’s one coffee break I’m glad I took.” He had been standing between the after battery and the mess when the wayward torpedo struck. He recalled, “Two other men were with me. One had headphones and was keeping us posted.” Suddenly, after the last torpedo was fired, there came the order, “All Ahead Emergency! Right full rudder!”

DaSilva said, “The torpedo hit between the after torpedo room and the maneuvering room. I clutched a ladder to keep from being pitched off my feet. Someone dogged down the water-tight door between the after and forward engine rooms. The

Tang was settling quickly by the stern and water was pouring in from the open doorway that connected the crew’s mess with the control room. I thought to myself, ‘Let’s get this door shut!’ Two or three of us seized the door and, with a great effort, shoved it closed, cutting off the flow of water.”

8The explosion was the most jolting, violent thing Clay Decker had ever experienced. It threw men across the control room, sending them smashing into gauges, switches, tables—breaking bones, splitting skulls, and knocking out teeth. Somehow he avoided being tossed about like a kitten in a cement mixer.

“The lads who were standing in the compartment where I was sitting were thrown across the compartment against the bulkhead,” he said. “It was terrible. The explosion knocked out all the lighting, and we immediately began sinking by the stern. The hatch above me was open and water was gushing in. Those lads in the conning tower fell into the control room, a drop of eight or ten feet. I heard them falling and hitting the steel deck.”

Like every qualified submariner, Decker knew exactly where the emergency lighting switch was, felt his way to the switch, and flipped it on. The sight appalled him. “At the bottom of the ladder, we had one man with a broken back, one with a broken neck, two with broken arms, and another with a broken leg. They were just lying there in a heap, moaning and bleeding.

“The last man who came down the hatch from the conning tower had a broken arm,” Decker said, “but with his good arm he grabbed the rope lanyard that was attached to the hatch. A piece of wood was tied onto the end of the lanyard. You’d grab that piece of wood and pull down to close the hatch, which is spring-loaded. Well, he’s coming down and the water is pouring in and he pulls on the lanyard and lets go. But the wooden end flips up and gets caught in the rubber gasket around the hatch opening. He got the hatch closed but not sealed, so we still had a stream of water pouring in on all the casualties piled up around the bottom of the ladder.”

He said, “Below the deck of the control room there are the bilges, storage lockers, arms lockers, a couple of air compressors, and some huge air tanks, so we knew it would take a while before the water would reach the deck. But we’re sitting at a forty-five-degree angle. We knew that the bow was sticking out of the water because we could hear the waves slapping against the hull and we’re rocking back and forth. It wouldn’t be long before the Japs started shooting at it. We also knew that we had to have the Tang level so that the men could go up to the forward torpedo room where the escape chamber was.”

Getting Tang level was another story. The chief of the boat, Bill Ballinger, had been hurt during the explosion. Decker said, “He had been standing watch by the ‘Christmas tree’ and was thrown when the torpedo hit us. He was lying in the corner, bleeding from the forehead, so I went over to help him. He had a big gash but he was conscious. He said, ‘Deck, we aren’t going to be able to get forward unless we get her level.’ That was all the order I needed.”

To lower the bow and make the boat level, Decker knew he had to flood the forward ballast tanks. “All the hydraulic controls could also be operated manually. The manual lever to open the valves on the forward ballast tanks was located directly above the chart desk in the control room. But it took a lot of force to move that lever, so I crawled up on the desk that was now at an angle, pulled the pin, and threw my legs around that lever. It swung down. The valves opened and the

Tang just leveled out and sat on the bottom.”

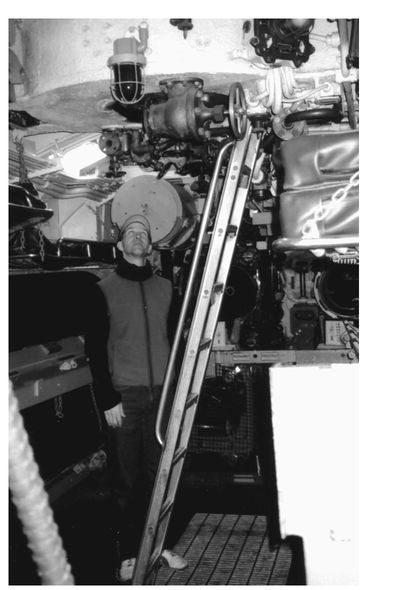

9Pete Sutherland, historian of the

Pampanito, shows the emergency

lever of the type that Clay Decker

used to level the Tang.

(Whitlock photo)

Unknown to Decker at that time was the fact that Skipper O’Kane, Caverly, and Leibold had been blown off the bridge; Engineer Officer Lieutenant Larry Savadkin had been in the enclosed conning tower operating the torpedo data computer. When

Tang went down, Savadkin found an air bubble at the top of conning tower. It was only about thirty or thirty-five feet from the hatch to the surface, so Savadkin decided to make a swim for it. Knowing how to turn his pants into a life preserver, he removed them, knotted the legs, blew up the pants with his breath, and sealed the top with his belt. He then took a deep breath, opened the hatch, and made it to the surface, where he joined O’Kane and the two other survivors.

10Dazed and distraught, the quartet managed to stay afloat while enemy destroyers stampeded about, firing their deck guns and dropping depth charges. O’Kane recalled the moment when he saw his boat go under: “

Tang’s bow hung at a sharp angle above the surface, moving about in the current as does a buoy in a seaway. She appeared to be struggling like a great wounded animal, a leviathan, as indeed she was. I found myself orally cheering encouragement and striking out impulsively to reach her. Swimming against the current was painfully slow and interrupted momentarily by a depth-charging patrol. Now close ahead,

Tang’s bow suddenly plunged on down to Davy Jones’s locker, and the lonely seas seemed to share in my total grief . . . My heart went out to those below and to the young men topside who must now face the sea,” wrote O’Kane in his memoir.

11Before long O’Kane and the others were picked up by the Japanese, who were eager to exact revenge against the submariners who had just sunk thirteen of their ships.

MEANWHILE, down inside the crippled sub, Decker and Ballinger began assembling the “walking wounded” and herding them toward the bow. “Everyone aft of the control room was apparently dead,” Decker assumed.

On their way through the passageway, the two men came across Ensign Mel Enos in the skipper’s stateroom, trying to set the codebooks on fire in a wastebasket. Decker grabbed the codebooks from the officer’s hands. “I said, ‘Mr. Enos, you can’t do that! We need every bit of air we’ve got! We can’t have a fire going! Besides, the batteries are right below us—you can’t have any sort of spark near them!’ ”

“But we have to destroy the codebooks,” Enos replied.

“Stuff ’em in the batteries,” the injured Ballinger offered. Popping the hatch in the deck, Decker crawled down into the battery room, removed the top to one of the huge batteries, and dropped the codebooks into the sulfuric acid, then scrambled out and closed the hatch.

The forward torpedo room was crowded with survivors, some bleeding, some burned, some nursing internal injuries. Clay Decker determined to look and act bravely in order to instill some calmness in the others, as well as in himself.

Submarine sailor aboard Narwhal demonstrating an early

model of the Momsen Lung. Photo taken July 1930.

(Courtesy Naval Historical Center)

He was gratified to see that, while the fear in the tight compartment was palpable, there was no panic among his shipmates. Each submariner is a volunteer, and each knows the hazards of his chosen branch of service. Two officers—Mel Enos and Hank Flanagan—were in charge. The depth meter said they were at 180 feet. Men began pulling brand-new ‘Momsen Lungs’ out of storage lockers and removing them from their cellophane bags.

“The Momsen Lung,” Deck explained, “was invented by a Navy officer, ‘Swede’ Momsen, before the war. It was designed to help crewmen escape from sunken subs. We had over a hundred of them on board.”

“The Momsen Lung

46 was an ingenious device,” Decker said. “It was a black rubber bladder that strapped to your chest, and it had a hose that went up to a mouthpiece that you put in your mouth. There was a nose clip to keep you from breathing in water through your nose. The bladder had a little valve on it, like a bicycle tire, and you charged the bladder with oxygen before you used it. There was also a canister of soda lime in the lung, and the carbon dioxide you exhaled would go through the soda lime, which absorbed the free carbon and created free oxygen. It also had a little flat rubber piece on it, a relief valve, right below the mouthpiece that would let air out but wouldn’t let water in. Once you got to the surface, you would close the relief valve and use the lung like a ‘Mae West’ life preserver.”

George Zofcin, whose wife and child were living with Decker’s wife and son back in San Francisco, helped Deck put on his Momsen Lung; Deck returned the favor.

12Jesse DaSilva recalled, “The Japanese came over us and continued to drop depth charges for some time. There were now about twenty of us in the mess room and crew’s quarters. We knew that we couldn’t stay here because of chlorine gas. We knew, too, that our one chance of escape was in reaching the forward torpedo room. But we had to pass through the control room to get there. This meant opening the control room door and, for all we knew, it might be flooded. Yet, we had to risk it.

“Someone cracked the door—water gushed in and rose around our legs, then gradually subsided. We discovered that the control room was only partially flooded. One by one, we moved up forward, knee deep in water. We filed into the control room and destroyed all the secret devices. I noticed at this time the depth gauge was at 180 feet. I thought to myself that there was still a chance [to get out] if we could reach the escapehatch located in the forward torpedo room. We passed through the officers’ quarters and into the torpedo room.

DaSilva noted that there were already twenty-some men in the in the forward torpedo compartment. “With our arrival, we brought the number to forty-five. There were some injured men, and the air was foul and breathing was difficult. Everyone was given a Momsen Lung. There had already been several attempted escapes and now they were going to make another.”

13Clay Decker said, “With the number of guys we had in the forward torpedo room, we figured we had only about four or five hours of air left. We had to do something within that period of time or we’d all die.”

Those sailors who were unhurt or only slightly injured set about making their wounded shipmates as comfortable as possible. The hanging bunks in the forward torpedo room were put back into place and the most seriously injured sailors were gently laid in them. A pharmacist’s mate bandaged those with lacerations and splinted those with broken bones. Those with broken necks were immobilized as much as possible with bolsters improvised from blankets and pillows.

“There was no use in any of them even trying to escape,” Decker said of the seriously injured. “There was no way any of them could have made it. It’s tough enough if you’re not injured.”

Decker remembered that Tang had “a couple of loudmouths, a couple of know-it-alls. This one loudmouth and a chief torpedoman had crawled up into the escape chamber before the rest of us could get organized. They didn’t have a Momsen Lung, or a Mae West on. They just flooded the escape chamber, opened the hatch, and went out on their own. We never saw them again. Lieutenant Flanagan took charge after that. He said, ‘We go in groups of four.’ ”

Ballinger called out, “I’m going in the first group. Who wants to go with me?” Clay Decker’s hand shot up, and he turned to George Zofcin. “C’mon, George, let’s go with Bill.”

But Zofcin held back. “I can’t go, Deck,” he said.

“For Christ’s sake, George, why not?”

“I have a confession to make—I can’t swim.”

It was true. Decker suddenly recalled the times when they had lounged on Waikiki Beach; George never went into the water. Now, with the situation in Tang growing more desperate by the minute, Decker tried a couple more seconds of persuasion, but Zofcin just crawled onto a bunk, as though he were waiting to die.

“Let’s go, Deck,” Ballinger said, grabbing him by the arm.

Decker gave George one last glance before climbing up the ladder and into the dimly lit, phone-booth-size escape chamber, along with two other men, newcomers to Tang. It was the last time he would ever see George Zofcin.

Inside the escape chamber were three main gauges. “One’s the fathometer that shows how deep you are,” explained Decker. “One’s a gauge that shows the air pressure inside the chamber and the third shows you what the external pressure is out at sea. What we had to do was close the bottom hatch that leads into the torpedo room, then let in seawater up to our chins. Then we opened another valve to let the air pressure build up and create an air pocket that exceeds the sea pressure by five pounds. That way, the hatch that opens to the sea will open as easily as opening a door in a room. Otherwise, you’d never be able to open it.

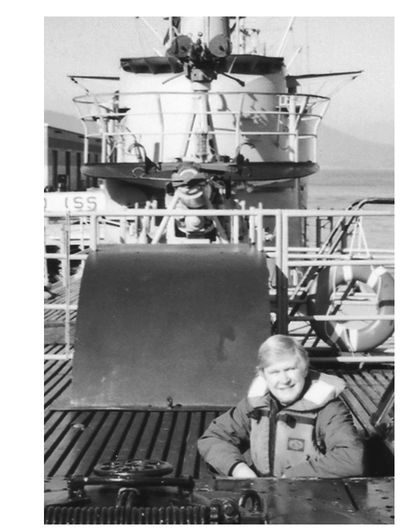

Pete Sutherland looks up the ladder that

leads to the escape hatch in the after

torpedo room of Pampanito.

(Whitlock photo)

“Once the hatch is open, you let out a wooden buoy about the size of a soccer ball that has a lanyard stapled around it and a handhold you can grab onto. The buoy is fastened to a line on a spool in the escape chamber, and the line has knots tied in it every fathom—every six feet. Right above the escape hatch is an opening in the superstructure about three feet square. The buoy and line go up through this opening and you have to hang on to the line and count the number of knots as you go up so you know how far you have left to go. At 180 feet, there are thirty knots in the line. It’s pitch-black out there, so you have no visual reference as to where you are. You can’t tell up from down. The main thing is to never let go of the rope, or you’ll get caught in the space between the pressure hull and the superstructure and never find your way out. You also don’t want to come up too fast or else you’ll get the bends.”

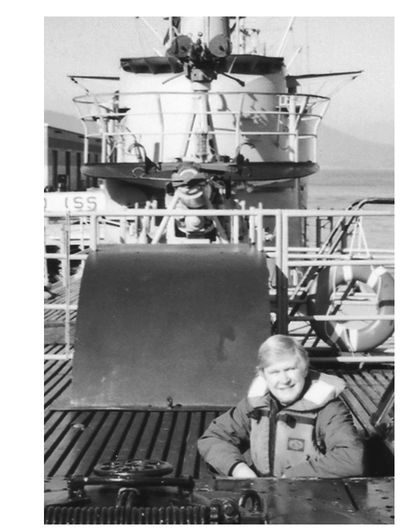

Author Flint Whitlock emerges topside

from the escape hatch of Pampanito.

(Whitlock photo)

After charging their Momsen Lungs from the air hose in the chamber, the four men opened the hatch and let out the buoy. Decker was the first one out, wrapping his legs around the line and climbing hand over hand, counting each knot and stopping to inhale and exhale at each one to prevent the bends.

After what seemed like an eternity in the icy water, Decker reached the surface just as the morning was turning light. The sea around him was chaotic with activity. Destroyers zipped here and there, at times coming dangerously close to him. All around was floating debris and the bobbing bodies of dead Japanese soldiers and sailors; ships burned fiercely on the horizon.

“When I got to the surface,” Decker said, “I reached up to take off my nosepiece and noticed that my nose and cheeks were bleeding. I guess I came up faster than I should have and got a nosebleed and the small blood vessels in my cheeks broke. I was a little worried that the blood would attract sharks, because the waters off Foo Chow are shark-infested; we were wearing 45-caliber pistols and knives just in case.” Decker’s Momsen Lung had filled with water and turned useless as a life preserver, so he discarded it, along with the heavy knife and pistol.

Decker clung to the buoy and waited for Bill Ballinger and the other two men in his group to surface. Suddenly Ballinger popped up about a yard away from him, gasping and coughing and flailing his arms, his eyes filled with terror.

Decker said, “Ballinger is drowning. The man is screaming and vomiting and holding out his hand for me to grab him. Something told me, ‘Don’t you reach out and touch that man! Absolutely don’t do it!’ It’s a well-known fact that a drowning man can pull a horse underwater. If he’d have gotten ahold of me, I’d have gone down with him. All I could do was watch the tide take him farther away from me, out to sea; I could hear him screaming off in the distance.

“Later on we figured what probably happened was that the relief valve on his Momsen Lung was folded and had a clip around it, like all the new ones did. Bill probably forgot to take the clip off and his lungs burst because there was no way for him to exhale on the way up to the surface.”

More minutes went by and the other two men in his group failed to appear. Then the buoy bobbed and Lieutenant Hank Flanagan from the second group came up; he was the only one from his group of four to make it.

14Inside Tang, Jesse DaSilva was in the next group preparing to go up. He said, “I found myself at the foot of the ladder leading up into the escape trunk. I heard someone say, ‘Let’s have another man,’ so I quickly climbed up into the trunk. I was the third man.” A fourth man stepped to the ladder, climbed in, and the hatch was closed.

“Everything went just as we were taught at the escape tank back at Pearl Harbor. We flooded the trunk, filled our Momsen Lungs with oxygen, and tested them to see if they were working. As the water rose in the trunk, breathing became difficult as the pressure was building up. When the water level reached above the outer door, we opened it. Someone had already let out the buoy with a line attached from the previous escapes, so now it was my turn to follow the line to the surface.”

DaSilva was the third man out. He slowly let himself up a fathom at a time, stopping and counting to ten at each knot. “About a third of the way up, breathing became difficult, but soon the problem went away and the water became lighter and suddenly I was on the surface. Nearby and holding onto the buoy were the men who had escaped before me.”

15DaSilva joined Decker and Flanagan at the buoy and the three of them prayed that more of their shipmates would soon join them. But only three more sailors surfaced—Torpedoman’s Mate Second Class Hayes O. Trukke, Torpedoman’s Mate Third Class Pete Narowanski, and Chief Pharmacist’s Mate Paul Larson; Larson had swallowed a lot of water and was in trouble.

A fourth man, one of the black mess stewards—either Ralph F. Adams or H. M. Walker—did surface, but far from the buoy. DaSilva tried saving him. “He came up some distance from us and acted like he couldn’t swim. As I reached him he disappeared, so I turned to swim back to the others. I didn’t realize I had drifted so far. It took a great effort to reach them. I realized that the tide was moving out to sea and there would be no chance to make the mainland of China that we could see off in the distance.”

16Six men were all who would make it out from the escape chamber and cling to the buoy; something must have gone drastically wrong down below. Decker said, “All I can assume is that all the others let go of the line on the way up and their bodies got hung up in the space between the pressure hull and the superstructure.”

17After several hours of clutching the buoy, the six Americans—Flanagan, Decker, DaSilva, Larson, Trukke, and Narowanski—were exhausted. Larson kept coughing, vomiting, crying. Finally, a Japanese destroyer escort that had been circling them approached.

DaSilva said, “It circled us several times and then stopped a short distance away, turning its guns towards us. I thought to myself, ‘Well, this is it—they are going to shoot us.’ But, instead, they lowered a small boat and came over and picked us up.”

18A dinghy manned by angry Japanese sailors using their rifles as paddles rowed over to the group. The enemy sailors began grabbing the

Tang crewmen and hauling them roughly into the boat like tuna.

19The Japanese sailors rowed back to the destroyer escort, the P-34, and the men climbed a rope ladder to the deck, where O’Kane and the other three survivors from Tang’s bridge and conning tower sat huddled together, their arms tied behind their backs. Decker was the last American up the ladder and looked back in time to see the Japanese sailors throw Larson, the choking pharmacist’s mate, overboard. He sank out of sight. There were now a total of nine survivors from the Tang.

Formosa and site of Tang sinking.

The destroyer escort had also picked up survivors from the ships that

Tang had torpedoed and these men were on the deck, staring at the Americans with hate in their eyes. “These were guys who had been down in those engine rooms who had been scalded when the boilers exploded—they were as red as cooked lobsters,” Decker related. “They’re looking at us and you could almost hear them thinking: ‘Those are the guys who did this to us.’ Then we got the worst treatment that we received the whole time we were prisoners. Those Jap survivors would come over and grab us by the hair and stick lit cigarettes up our noses. Then they would slap and kick and beat the shit out of us.”

20O’Kane noted with some compassion, “When we realized that our clubbings and kickings were being administered by the burned, mutilated survivors of our own handiwork, we found we could take it with less prejudice.”

21DaSilva said, “One by one, the Japanese would take us aside and interrogate us. When it was my turn, they took me to another part of the ship and had me sit down between three of them. They offered me a ball of rice, but I could not eat it. One of them had an electrical device and he would jab me in the ribs with this and I would twitch and jump. They all thought this was very funny. The one that could speak English carried a large club about the size of a baseball bat. He would ask questions and if he didn’t like the answers, he would hit me on the head with this bat. After some time, when they figured that I wasn’t going to tell them anything, they took me back to the others.

“Later on, we were all taken to a small room and locked in there. It was so small that only two or three of us could lie down; the rest had to stand. It was very hot and there was only one small porthole for air which they would not let us open. Finally, we persuaded the guard to let us out, so they took us out and we were allowed to sit on the deck in the fresh air.”

22This was a mixed blessing, for, as Decker recounted, “All we were wearing was our shorts. Some of us still had sandals on. Because we submariners never spent much time in the sun, we were fair-skinned; they kept us up on this hot steel deck under the blazing sun for five days, at the end of which time we were a mass of blisters. We got no water, no food. We thought, this is the end.”

23