CHAPTER 21

BEAR THE UNBEARABLE

ON 30 April 1945, while American forces were closing in like buzzards around Japan, and American, British, and Soviet troops were squeezing the Third Reich to death, Adolf Hitler, deep in his Berlin bunker, bit down on a cyanide capsule at the same moment he blew his brains out with a pistol.

With Hitler dead, Nazi Germany’s days were numbered. Pounded without pause from the air and penetrated from two sides on the ground, Germany became a diminishing perimeter, a cancerous tumor being slowly starved and shrunken. The Soviets had driven deeply into what was left of the burning, rubble-strewn capital and were closing in on Hitler’s final hiding place, the

Führerbunker beneath the battered Reich chancellery. Except for a few hard-line units that refused to give up when they got the word of their Führer’s suicide, the Third Reich was no more. The war in Europe was finally over; the war in the Pacific, however, went on.

1

RON Smith’s war, however, was finished. The Smith’s son, Ronal Lynn, was born on May 17, 1945, in Marilynn’s hometown of Salida, Colorado. During that time, Smitty was transferred from Great Lakes to the Crane Naval Ammunitions Depot, near Burns City, Indiana, about thirty-five miles southwest of Bloomington, where he received a stunning letter.

“Marilynn and the baby were supposed to come join me,” Smitty said, “but I received a ‘Dear John’ letter from her while I was at Crane. I guess she didn’t want to be married to me anymore. The letter was kind of a shock, but it didn’t really affect me all that much. I was young and could not separate sex from love at that time. I had more than enough ‘girlfriends,’ so I didn’t lose a lot of sleep over it. In a way, I was relieved—I wouldn’t have the responsibility of a family.”

2

FRANK Toon was still in the Pacific, and was still in combat. On 25 May 1945, his Fremantle-based boat, Blenny, was on its third war patrol in the South China Sea. Toon recalled, “The whole patrol was a merry-go-round for the gun crews. I was the ‘trainer’ on the forward five-inch gun, and we had lots of opportunity to shoot. As I recall, we sank sixty-three small targets in thirty days. A lot of these small targets would be sunk with just one five-inch shot. Of course, we kept running out of ammo and were always looking for a submarine that had extra ammo left over when heading home. We would then transfer it aboard Blenny by breeches buoy. It was always amusing to hear Captain Hazzard call below to ‘send up one five-inch bullet.’ Darn big bullets!”

Toon remembered an incident that was humorous only in hindsight—the time his commanding officer was blown through the hatch. “We had spent all day lying on the bottom to repair problems with the port shaft,” he said. “I was the ‘watch quartermaster’ when we surfaced, and there was a lot of air pressure that had built up inside the boat. I opened the hatch and jumped back to allow the captain to be first up. Just as he started up, the lower hatch blew open and the captain was ‘launched’ up through the hatch, banging his head. ‘Doc’ Taylor had a chance to practice his sewing! If that lower hatch had blown open a second or two earlier, it would have been

me that went out the hatch!”

3

ON Monday, 16 July 1945, the predawn skies around Alamogordo, New Mexico—110 miles south of Albuquerque—suddenly were illuminated with the brilliance of a thousand suns.

The first atomic bomb—the product of the top secret Manhattan Project—had just been successfully tested. The multibillion-dollar project, under the command of Major General Leslie R. Groves and a team of scientists headed by University of California at Berkeley professor of theoretical physics Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, had been progressing to this point for nearly four years.

Following the discovery of the neutron in 1932, it was determined that it was possible—given enough money and scientific brainpower and fissionable material—to build a superweapon. The only question had been, who would build it first—the Germans, the Japanese, or the Americans? The fear at the highest echelons of the American and British governments in the early 1940s was that the Germans and Japanese were both working on similar projects, and that either—or both—would use such a weapon against the Allies as soon as they had the chance. The Americans and British were determined to beat the Germans and Japanese to the atomic punch; the collapse of Germany in May 1945 meant that all of the work could be directed at knocking the sole combatant enemy nation—Japan—out of the war.

So secret was the Manhattan Project that Vice President Harry S. Truman, who had inherited the presidency of the United States when Roosevelt died suddenly of a massive cerebral hemorrhage on 12 April 1945, had not even known of its existence. He was quickly brought up to speed.

A debate went on behind closed doors. While some felt that an atomic bomb—if it actually worked—was morally reprehensible because it could indiscriminately kill hundreds of thousands of innocent civilians, the majority argued that such a result was far more moral than allowing the war that had been raging for six years—a war in which 50 million people had already perished—to drag on for months, or even years, and cause even greater casualties, sorrow, and devastation.

The invasion of Japan was even now in the final stages of planning, and scores of combat-weary divisions in Europe were alerted for deployment to the Far East. On 18 June 1945, President Truman met at the White House with General Dwight D. Eisenhower; General George C. Marshall, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; Secretary of War Henry Stimson; Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal; and a handful of other high-ranking advisers to discuss the matter and come to a resolution.

4Everyone was painfully aware of the hard truth: Japanese fighting men, even when trapped on cut-off Pacific islands with absolutely no hope of reinforcement or victory, clung tenaciously to their bushido code and never surrendered. They almost always fought to the death—and sometimes beyond; the bodies of dead comrades were frequently booby-trapped to blow up when moved by American soldiers and Marines checking for life or war souvenirs.

If the invasion of Japan took place, it was assumed—and with good reason—that every Japanese man, woman, and child would fight as guerrillas to inflict maximum casualties on the invaders. It was also estimated that Japanese casualties in such an invasion would approach or exceed one million, with American casualties running about the same. Admiral Shibasaki’s assertion that “a million men could not take this island in a hundred years” would be better applied to Japan itself than to Tarawa. William Manchester writes, “We assumed we would have to invade [the Japanese Home Islands of] Kyushu and Honshu, and we would have been unsurprised to learn that MacArthur, whose forecasts of losses were uncannily accurate, had told Washington that he expected the first stage of that final campaign to ‘cost one million casualties [dead and wounded] to American forces alone.’ ”

5Thus came the ultimate question: Would it not be preferable—even merciful—to use a weapon that could snuff out this horrible war in an instant, the way one blows out a candle?

At the time the choice seemed simple. What if a superweapon with power beyond imagining could call a sudden halt to all the suffering and bloodshed that the Second World War had brought about? It was Japan that had thrust America into the global conflict on 7 December 1941, and it was Japan that must pay the ultimate price for her perfidy—even if it meant the unfortunate and tragic sacrifice of one or two Japanese cities full of innocent civilians.

Someone at the meeting advanced the idea of telling the Japanese government that the United States possessed a weapon of such unimaginable power that it could totally destroy the entire nation of Japan. Someone else suggested dropping warning leaflets or holding a demonstration and exploding one of the bombs—there had been only enough fissionable material to build three of them—on some sparsely populated island near Japan and inviting Nippon’s leaders to witness it. This was countered by someone pointing out that the Alamogordo bomb had worked because it was mounted on a stationary tower and had been detonated under controlled scientific conditions; what if one of these complex, delicate instruments, when dropped by an aircraft, turned out to be a dud? Wouldn’t that just convince the Japanese that the United States was bluffing and merely serve to strengthen Japanese resolve? Good point, the group agreed.

6Statistics vary widely, but already over 400,000 American servicemen and women had been killed in the war (with over 600,000 wounded), along with more than 360,000 British troops (including colonials), 200,000 French, 1.4 million Chinese, 10 million Soviets, over two million Germans, 200,000 Italians, and over two million Japanese troops, to name but a few. This list does not include the approximately 55.3 million civilians worldwide who had died as a result of the war .

7The time, everyone finally agreed, had come to end the war—and the world’s agony—with one tremendous blow.

8If Truman hesitated to consider the moral dilemma posed by the use of such a tremendous and horrible weapon, or agonized over his decision, such a hesitation was only momentary. He gave the order.

On 24 July 1945, General Thomas T. Hardy, acting chief of staff of the Army, sent a communiqué to General Carl Spaatz, commander of the United States Army Strategic Air Force:

The 508 Composite Group, 20th Air Force, will deliver the first special bomb as soon as weather will permit visual bombing after about 3 August 1945 on one of the targets: Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata and Nagasaki ...

9

The order was relayed to the island of Tinian, where Colonel Paul Tibbetts and his aircraft, a B-29 Superfortress bomber with the name of his mother, Enola Gay, painted on the nose, waited.

It was decided to give Japan one last chance to surrender—or suffer the unstated consequences. On 26 July, Japan was sent an ultimatum known as the Potsdam Declaration, signed by representatives of China, Britain, and the United States, which demanded that she surrender immediately or be annihilated; the Japanese prime minister, wrongly assuming the document’s war-weary signers were bluffing, flatly rejected the demand.

At 0815 hours, Japan time, 6 August 1945, much of the city of Hiroshima suddenly ceased to exist. A single uranium bomb dropped by Tibbetts and the crew of

Enola Gay detonated in the clear sky above the heart of the city. In a flash, 78,000 people were dead, 37,000 were injured, and another 13,000 were missing. Sixty percent of the city had been flattened and turned into a charred, nearly unrecognizable landscape.

10Still, the Japanese government did not concede. Perhaps they thought the Americans had but one atomic bomb. Perhaps they were still confused and reeling and unclear about what had happened to Hiroshima. In either case, a second demand for surrender was also rejected.

On 8 August, the Soviet Union, in the diplomatic equivalent of beating up a corpse, declared war on Japan.

The following day a B-29 with the name

Bock’s Car painted on its nose, and piloted by Major Charles W. Sweeney, flew at 29,000 feet above the city of Nagasaki and released another atomic bomb, this one with a plutonium core. Nearly 100,000 people died or were wounded in the searing blast and the firestorm that followed. As Lansing Lamont writes in

Day of Trinity, “Nagasaki in all its horror told the Japanese that Hiroshima had been no fluke or lone experiment. It said in effect: Here is a second example of what the bomb can do, and there are more.”

11Even the destruction of Nagasaki did not bring about an immediate cessation of fighting. In China, on 10 August, the Communists mounted a final offensive against their occupiers; the next day Soviet warships bombarded Japanese installations on southern Sakhalin Island. On 12 August, Soviet infantry and armor launched an annihilating attack against Japanese defenders holed up in a Manchurian fortress. On the fourteenth, over 800 American B-29s clobbered enemy installations throughout Honshu with conventional high-explosive munitions.

The horror—and the fear of further atomic and conventional bombings against which Japan had no defense—finally sank in. With her cities flattened, her army and navy crushed, and enemies encircling her like vultures, Japan had no alternative but to give up. During a meeting with his Supreme War Council and the entire cabinet on 14 August, Emperor Hirohito declared that his country must accept the Potsdam Declaration and “bear the unbearable.”

Hearing rumors that the emperor might order Japan’s capitulation, a thousand hard-line troops stormed the Imperial Palace grounds in hopes of preventing the surrender; they were beaten back by the Imperial Guards in a bloody confrontation.

The next day, a prerecorded message from the emperor was broadcast on nationwide radio in which he informed his people of his painful decision. On the sixteenth, the confirmation that the emperor had directed the armed forces of Japan to cease fire immediately was transmitted by radio to General MacArthur’s headquarters. Japan surrendered unconditionally. The Second World War was, at long last, finished.

12

FRANK Toon, aboard the submarine

Blenny, recalled, “We had just received a message by light from the tender: The war was over! We were making a sound run in Subic Bay in the Philippines when all the fireworks started. I still remember shooting off all our Very shells and flares to join in the celebration. We put on the smoke generators before making a run around the bay on our way back to the tender. That smoke screen surely clouded things up! Everyone was happy!

THE WAR WAS FINALLY OVER!”

13

“WE didn’t have a radio at the hospital and no one got a newspaper—I got the news about the A-bomb from the other men,” said Ron Smith, who was back in the hospital at Great Lakes for further testing and evaluation. He was astounded when word of the secret weapon that had brought about the end of the war raced through the hospital.

Smitty said, “I didn’t understand what the atomic bomb was at that time, but I was overjoyed that we had a new ‘superweapon.’ I felt no pity whatsoever for the Japs; we could have exterminated the whole race and it wouldn’t have bothered me one bit. When they surrendered, I was thankful that the war was finally over. There was no big celebration at the hospital, just relief—a great sense of relief from the nagging anxiety that had been with me for several years. I just wanted to go somewhere and sleep in peace.

“Ironically, they had all of us patients restricted to the hospital, but they let all the men from boot camp out to celebrate in Chicago while they kept the combat veterans ‘chained down.’ Since I only had about six months left on my enlistment when the war ended, I was offered a discharge. I took it.”

14

AT Omori, the American prisoners had heard rumors about the atomic bombs and were very hopeful that the rumors were true and that such awesome weapons might soon lead to their liberation.

Jesse DaSilva said, “We knew that the war was getting closer to the end. We knew what was happening all the time as bits of information would filter through the camp. We knew when the atomic bomb had been dropped and we couldn’t believe the results.”

15Clay Decker noted, however, that the prisoners had one big worry. “In August many of the guards were crying, almost hysterical, probably because they had friends and relatives in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. We were afraid that they might take revenge against us and kill us all. After all, they had lost the war, so what else did they have to lose? We figured they would kill us and then commit suicide.”

16Jesse DaSilva said, “One morning we woke up and it was very quiet. We discovered there was only one guard in the whole camp. He told us the war was over, so we just took over the camp.”

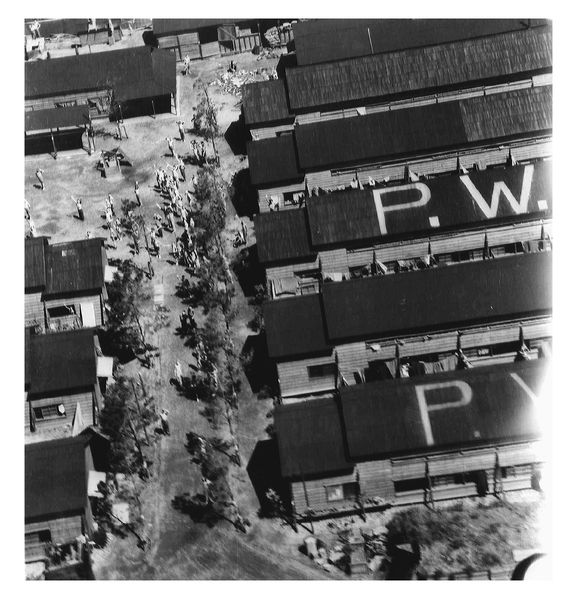

17Some of the prisoners found brushes and white paint in a camp storehouse, crawled onto the roofs of the buildings, and painted giant signs reading P.W. and PAPPY BOYINGTON HERE, in hopes that American airmen, flying over Tokyo Bay, would see them and come to their rescue.

18It worked. DaSilva recalled that aircraft flew over the camp and dropped tons of food and clothing. “It got so bad that this stuff was crashing through the buildings, so we had to put a sign on the compound telling them to drop it outside of camp,” he said.

19Clay Decker said, “They airdropped a lot of food and medicines to us. Some of our lads got sick gorging themselves on all the food, so we needed to be careful about how much we ate and not overdo it.”

20Roof signs at Omori POW Camp.

(Courtesy National Archives)

THE atomic bombs weren’t the only weapons that brought Japan to her knees. The American submarine force had much to do with it. A 1999 study by Michel Poirier points out that the Japanese Merchant Marine fleet lost 8.1 million tons of vessels during the war; American submarines accounted for 4.9 million of those tons, or 60 percent of the total.

The submarines were also instrumental in preventing the raw materials that Japan’s war industries desperately needed from reaching the factories that would turn them into tanks, ships, airplanes, guns, bombs, bullets, uniforms, and the other necessities of war. Japan’s imports of sixteen key materials fell from 20 million tons in 1941 to 10 million tons in 1944, and to a meager 2.7 million tons during the first half of 1945. Imports of bauxite, essential for the production of aluminum, plunged 88 percent between the summer and fall of 1944. The next year, pig-iron imports fell 89 percent, raw cotton and wool were down over 90 percent, lumber down 98 percent, and so on. Not one ounce of sugar or raw rubber reached Japan during the first six months of 1945.

Because of the submarines, millions of Japanese bullets and tens of thousands of bombs and artillery shells never arrived at the battlefronts to kill Americans. Millions of gallons of oil and gasoline bound for Japanese tanks, trucks, ships, and aircraft also never reached their destinations. From August 1943 to July 1944, oil imports dropped from 1.75 million barrels of oil a month to just 360,000 barrels per month. As Poirier says, “After September 1943, the ratio of petroleum successfully shipped that reached Japan never exceeded twenty-eight percent, and during the last 15 months of the war the ratio averaged nine percent. The losses are especially impressive when one considers that the Japanese Navy alone required 1.6 million [barrels] monthly to operate.”

By the last year of the war, the Japanese tried to cope with the shortages through desperate measures. Because of the lack of fuel, flight schools sent new pilots off to their units—and their doom—with only a fraction of the number of hours needed to attain proficiency in the sky. Because of the severe lack of petroleum products, the number of hours a new airplane engine could be tested was drastically reduced. And, due to the shortage of high-quality aluminum, planes were built with an increasing number of wooden parts. Likewise, thousands of Japanese troops being shuttled to island battlefields never made it. Food and medicine needed to keep isolated Japanese garrisons alive and healthy similarly failed to arrive.

Shipbuilding in Japan was reduced to a mere trickle of what it had been early in the war. With the nearly total cutoff of iron ore, the ability of the Japanese shipbuilding industry to replace the country’s massive losses after the autumn of 1944 was severely crippled. Poirier writes, “The requirement to build escort ships and naval transports (also to replace merchant losses) reduced the potential to build more powerful combatants.

“As a result, while the IJN used fourteen percent of its construction budget for escorts and transports in 1941, the percentage shot up to 54.3 percent in 1944. More astonishing, the need for escorts and merchants was so grave that, after 1943, the Japanese Navy started construction on no ship bigger than a destroyer!”

Transports, merchantmen, and oilers weren’t the only vessels decimated. During the course of the war, American submarines sank 700,000 tons of Japanese warships, including one battleship, eleven cruisers, eight aircraft carriers, and scores of smaller ships.

Food, too, was in short supply in the Home Islands, with the average caloric intake of urban dwellers plunging 12 percent

below the minimum daily requirement.

21Without a doubt, then, American submarines had a huge impact on Japan’s ability to wage war. The American submarines were the noose that slowly strangled Japan to death.

The price of victory, however, was high. Of the approximately 15,000 men who served in the 288 American submarines from 1941 to 1945, 374 officers, 3,131 enlisted men, and fifty-two submarines—22 percent of the total—were lost.

22

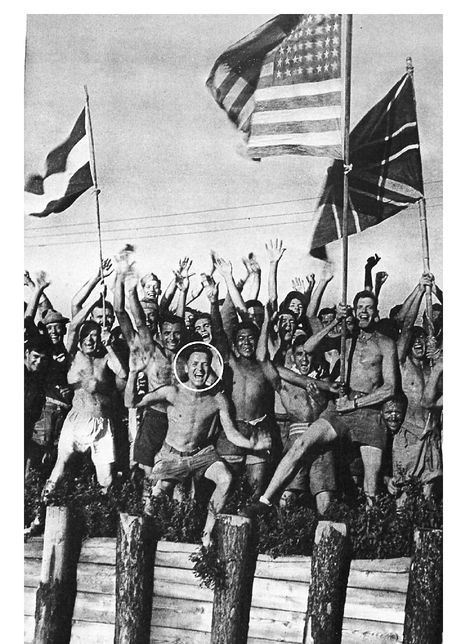

THE American fleet, with Admiral Halsey in command, sailed into Tokyo Bay on 29 August 1945 aboard the battleships Missouri, Iowa, and South Dakota, light cruiser San Juan, and hospital ship Benevolence to prepare to occupy what was left of the burned-out capital. On that same day, the San Juan, Benevolence, and two high-speed transports, U.S.S. Reeves and Gosselin, approached Omori. Three naval officers—Roger Simpson, Joel Boone, and Harold Stassen—the latter the former governor of Minnesota who had resigned the office to join the Navy in 1943—debarked and approached the camp’s gates to investigate conditions inside.

Another officer who accompanied them into the camp wrote, “When the prisoners realized what was happening, indescribable and pitiful scenes of enthusiasm and excitement took place—men even jumped into the water and started swimming out to the boats . . . They found the camp conditions unspeakable with every evidence of brutality and wretched treatment. What our people found there will contrast the Nips’ present ingratiating attitude.

“Simpson, Stassen, and Boone did a magnificent job—without regard to their own safety they waded into the situation, bluffed the Japanese camp guards, and gave them a complete brushoff. Joel Boone made his way to a Japanese hospital three miles away, and singlehandedly took over the situation, telling the Nips that he didn’t give a goddamn what their orders were . . .

“The work went on all night and some seven hundred prisoners were processed through the

Benevolence, the desperately sick being hospitalized, and the ambulatory cases moved to the APDs [

Reeves and

Gosselin ]. On the following day the work continued and by the evening of the 30th about one thousand POWs had been freed.”

23Happy liberated American, Dutch, and British

POWs at Omori. Clay Decker is in foreground

(circled).

(Courtesy Clay Decker)

Jesse DaSilva said, “I was taken aboard the hospital ship

Benevolence and was put to bed and given blood and other medication. I was also given a meal of bacon and eggs. When I was captured I weighed 170 pounds. Now I was down to about 100 pounds and was in no condition to be flown home. Later I was transferred to the hospital ship

Rescue, which was returning to the States. It took twenty-one days, but I didn’t care—I knew I was going home! I arrived back in the States exactly two years since had I left on October 25, 1943, and one year to the day that our submarine was sunk—on October 25, 1944.”

24Clay Decker, naturally, was overjoyed at being liberated. “The first thing I thought about was that, at last, I would get to go home and see Lucille and little Harry.

“Pappy Boyington and nineteen other officers were the first to be returned to the States by transport plane. Somehow I got to be a part of that group. Twenty officers and one enlisted man. I asked Pappy, ‘Did you get me on this flight?’ And he said, ‘Aww, Deck, I didn’t have anything to do with it.’ But he said it with a smile, so I know damn good and well he did.”

After a couple of days flying over nothing but ocean, and stopping briefly at Wake, Midway, and Hawaii to refuel, the transport at last approached the California coast. Everyone on board had their faces pressed against the small windows. Decker said, “There was the Golden Gate Bridge down below us. What a sight! And the hills around San Francisco Bay, with all their little houses and buildings and roads. It looked like the world’s most beautiful model-train layout; I couldn’t believe it was actually real, that I was actually home.”

25It was not the happy homecoming Decker had expected it to be, for he was in for one final shock.

ONE might think that the end of the war would have brought an out-pouring of jubilant gloating among the victors at the highest echelons of government, but just the opposite was the case. The war had been too long, too bloody, too expensive for either jubilation or gloating. The awesome destruction and death toll wrought by the two atomic bombs, and by the carpet bombing of Japan’s cities and the Third Reich, were too terrible to celebrate in any grand fashion. There was no time to rest on the laurels of victory, either, for a new world needed to be built atop the ashes of the old, destroyed one.

Immediately after the war Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson said with extreme gravity, “In this last great action of the Second World War, we were given final proof that war is death. War in the twentieth century has grown steadily more barbarous, more destructive, more debased in all its aspects. Now, with the release of atomic energy, man’s ability to destroy himself is very nearly complete. The bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended a war. They also made it wholly clear that we must never have another war. This is the lesson men and leaders everywhere must learn, and I believe that when they learn it they will find a way to lasting peace. There is no other choice.”

26More than sixty years later, the world is still waiting for the lesson to be learned.