FEBRUARY 21, 1862: Continuing a military campaign in the Arizona and New Mexico territories intended to open the door to California for the Confederates, troops under Southern general Henry Hopkins Sibley defeat a Union detachment at Valverde, New Mexico. Among the Union troops killed is Captain George N. Bascom, who, as a young lieutenant a year earlier, created the incident that sparked the ongoing war between the United States and the Apache Nation. (See February 4, 1861.)177

FEBRUARY 22, 1862: “At the darkest hour of our struggle the Provisional gives place to the Permanent Government,” Jefferson Davis declares at his inauguration as permanent president of the Confederate States (see November 6, 1861). Accusing the North of promoting a revolution against states’ rights and slavery, thus perverting the goals of the Founding Fathers, and oppressing the South with “the tyranny of an unbridled majority,” he celebrates the spirit of the Southern citizenry—and acknowledges a downturn in Confederate fortunes. “After a series of successes and victories, which covered our arms with glory, we have recently met with serious disasters. But in the heart of a people resolved to be free these disasters tend but to stimulate to increased resistance.” The following day, Robert E. Lee will write to his son, expressing concern over Confederate resolve. “The victories of the enemy increase & Consequently the necessity of increased energy & activity on our part. Our men do not seem to realize this, & the same supineness & Carelessness of their duties Continue. If it will have the effect of arousing them & imparting an earnestness & boldness to their work, it will be beneficial to us. If not we shall be overun [sic] for a time, & must make up our minds to great suffering. All must be sacrificed to the country.”178

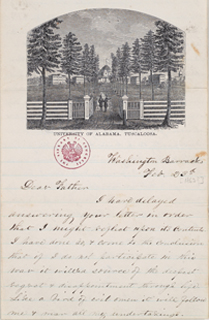

FEBRUARY 23, 1862: In an exchange being echoed in many families North and South, seventeen-year-old student James Billingslea Mitchell writes to his father from the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa: “Dear Father. I have [reflected on your letter] & come to the conclusion that if I do not participate in this war it will be a source of the deepest regret & disappointment through life. Like a bird of evil omen it will follow me & mar all my undertakings. You said that you would not except in case of the direst necessity consent to have my course interrupted…. What direr necessity can there be than the present, unless it be the very burnings of our own homes…. It is true hundreds of my age have fallen victims to disease and death while yet upon the threshold of the service. But why should not I die as well as they? Shall I sit ignobly here and suffer them to fight my battles & endure all for me? Never.”179

James Billingslea Mitchell (1844–1891), CSA. Manuscript letter to his father, February 23, 1862.

Legal Tender Polka. Color lithograph music cover. Music by F. Chase; lithograph by A. McClean, 1863.

FEBRUARY 25, 1862: After taking possession of Bowling Green, Kentucky, on February 16, Union general Don Carlos Buell and his troops occupy Nashville, the first Confederate state capital and important industrial center to fall to the Union.180 In Washington, as the Union struggles with the problems of financing the war (difficulties so acute that, for a period, the government had to suspend payments to soldiers and contractors), Abraham Lincoln signs the Legal Tender Act, creating the first successful government-sponsored national paper money system in U.S. history. The notes, popularly called “greenbacks,” are unsecured by specie (gold or silver), something that creates anxiety among the many people who question the legislation. Treasury Secretary Chase is among those discomfited, but he is also the person who best knows the scope of the Union’s economic problem. “Immediate action is of great importance,” he has said. “The Treasury is nearly empty.” A significant extension of Federal authority, and meant as a temporary wartime measure, the bill authorizes the government to issue $150 million in greenbacks. This will prove insufficient. More than $400 million will be put in circulation by the war’s end.181 In New York, USS Monitor is commissioned. Looking to some like “a cheesebox on a raft,” the ironclad has radically new features: a revolving turret housing two eleven-inch Dahlgren smoothbore cannon and forced draft ventilation that allows the crew to live in an artificial, “submarine” environment. Monitor is also uniquely ironclad—not simply converted from a preexisting vessel, as was CSS Virginia.182

FEBRUARY 27, 1862: The Confederate Congress authorizes the president to suspend the writ of habeas corpus in areas that “in his judgment, be in such danger of attack by the enemy as to require the declaration of martial law for their effective defense.” Davis immediately suspends the writ in Norfolk and Portsmouth, Virginia, and he suspends it in Richmond on March 1—cities that are in danger not only of attack from without but also of collapse within due to rising crime and violence among their wartime populations, which have ballooned with refugees, war workers, black marketeers, and others, making a volatile mix.183

Captain Franklin Buchanan (1800–1874), CSN. Photograph between 1860 and 1870. A career naval officer, Buchanan was the first superintendent of the U.S. Naval Academy before resigning his U.S. commission to join the Confederate service.

MARCH

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

Battle of Pea Ridge, Ark. Color lithograph by Kurz & Allison, n.d. This Confederate defeat helped keep the troubled border state of Missouri securely in Union hands.

MARCH 6, 1862: In a message to Congress, Lincoln calls for cooperation with any state that will gradually abolish slavery and proposes offering compensation to slaveholders. He notes that the cost of the war would quickly “purchase, at a fair valuation, all the slaves in any named state.” Adopted by Congress on April 10, the resolution is not accepted even by the border states, which are its principal focus. Also today, USS Monitor sails from New York for Hampton Roads, Virginia.184

MARCH 7–8, 1862: Cherokee allied with the South are among the Confederate troops who fight in the two-day battle of Pea Ridge (Elkhorn Tavern), Arkansas. In this action, the culmination of a Union campaign by General Samuel R. Curtis to drive Major General Sterling Price’s Confederates out of Missouri, Price’s men, joined by a force under Brigadier General Ben McCulloch and Major General Earl Van Dorn, find that Curtis has anticipated their planned attack against the pursuing Federals. The Confederates are roundly defeated.185

MARCH 8, 1862: As preparations begin for a massive Union push up the Virginia peninsula to take the Confederate capital city of Richmond via the Virginia peninsula (the Peninsula Campaign, March–August 1862), President Lincoln relieves McClellan of his duties as general in chief, leaving him in command of the Army of the Potomac only. This is ostensibly so that the general can concentrate his full attention on the forthcoming campaign. The president (who has proven to be a singularly adept student of military strategy) and Secretary of War Stanton now assume the duties of general in chief themselves. In the same military directive, Lincoln creates the Mountain Department in western Virginia and places John C. Frémont in command—a move that pleases Radical Republicans who disagreed with the president’s removal of Frémont from command in Missouri the previous fall (see August 30, 1861).186 At Hampton Roads, Virginia, the U.S. Navy suffers the worst day in its eighty-six-year history when the ironclad CSS Virginia (formerly USS Merrimack), captained by Confederate flag officer Franklin Buchanan, attacks the wooden ships of the Federal blockading fleet. Sweeping through Union fire, severely damaging the frigate USS Congress on the way, Virginia smashes into the side of the large sloop of war USS Cumberland, tearing a hole that causes the vessel to sink, its crew continuing to fire at their attacker until the last minute—and managing to blow the muzzles off two of Virginia’s guns. Yet the Confederate vessel is still formidable, dispatching shore batteries along the James River and destroying a transport ship before turning on USS Congress, which had run aground, raking the Union frigate with fire. After an hour-long battle, Congress, severely damaged and with heavy casualties, is forced to surrender. As the Confederates set it ablaze, Buchanan is wounded; command of Virginia passes to Commander Catesby ap Roger Jones—who immediately sets the vessel’s sights on Minnesota, also aground and already taking fire from Confederate gunboats. Virginia adds to the damage they are doing, but as night falls, the Southern ironclad withdraws. The consternation that reigns among Union naval forces at the destructive power of the South’s armored vessel is tempered later in the evening when, under cover of darkness, the Union ironclad USS Monitor arrives on the scene. The stage is set for the first clash in history between ironclad vessels.187

Battle Between the Monitor and Merrimac—Fought March 9th 1862 at Hampton Roads, near Norfolk, Va. Color lithograph published by Kurz & Allison, 1889.

Admiral John L. Worden (1818–1897), USN. A lieutenant at the time of Monitor’s battle with CSS Virginia, Worden was promoted to admiral in 1872 while serving as super-intendent of the U.S. Naval Academy.

MARCH 9, 1862: In April 1861, Lieutenant John L. Worden became the first Federal officer taken prisoner by the Confederates while he was on a mission to Pensacola, Florida. Today he carves a deeper niche for himself in history when he commands USS Monitor in its historic encounter with CSS Virginia, a clash that presages a new era in naval history. For two hours, the two ironclads battle each other, each taking hits and delivering blows—though neither is significantly damaged. Finally, they stop fighting, neither vessel able to claim a victory this day. But the cumulative victory of two days of fighting clearly belongs to Virginia, and the damage it did to the Union’s wooden vessels will be celebrated throughout the Confederacy. “Our single iron clad vessel—the Virginia has… sunk the Cumberland, burned the Congress, crippled the Minnesota, repulsed the Roanoke & the St Lawrence, and drove all the other vessels under the shelter of the guns of Fortress Monroe,” Catherine Edmondston exults in her diary on March 10. “This is glorious news & will cheer the heart of the nation now cast down with the reverses in Tennessee.”188

MARCH 13, 1862: A new U.S. article of war forbids army officers, under penalty of court-martial, to return fugitive slaves to their masters.189

MARCH 14, 1862: Union troops under Ambrose Burnside, having secured Roanoke Island, North Carolina (see February 7, 1862), move to the mainland and attack Confederate defenses protecting the city of New Bern, an important railroad depot strategically located at the confluence of the Trent and Neuse rivers. Among the Federal soldiers wounded before the defenses are successfully penetrated is a sergeant of the Fifth Rhode Island Infantry—who is promptly dragged to safety by his wife, Kady Brownell. One of an estimated four hundred to six hundred women who will have campaigned with Civil War armies by the end of the war, Brownell has become so much a part of the Fifth Rhode Island’s camp life that the men have dubbed her a “daughter of the regiment.” She rescues several other wounded men during this day’s fighting before returning home with her injured husband. New Bern will remain in Union hands for the rest of the war, a bitter loss to the Confederacy.190

MARCH 17, 1862: A convoy of army transports and navy warships begins the monumental task of moving Major General George B. McClellan’s 105,000-man Army of the Potomac, and its equipment, to the York and James rivers for the start of the Peninsula Campaign of 1862.191 At about this same time, Jefferson Davis appoints Robert E. Lee as his principal military adviser, placing him in charge of “military operations in the armies of the Confederacy.” McClellan, who served with Lee during the Mexican War, assumes this means that Lee will take command of the forces defending Richmond (a premature assumption; Joseph Johnston retains that field command). McClellan will write Lincoln in April that Lee “is too cautious & weak under grave responsibility… & is likely to be timid & irresolute in action”—a character sketch that some restive Republicans have been drawing of McClellan himself.192

Kady Brownell (1842–1915), “daughter of the regiment,” USA. Child of a Scottish soldier, Brownell accompanied her husband, Robert, into service in the Union Army.

General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson (center, 1824–1863), CSA, and staff—including talented mapmaker Jedediah Hotchkiss (to the left and slightly above Jackson’s picture). Photograph by Vannerson & Jones, from original negatives, ca. 1861–1863.

MARCH 18, 1862: Judah P. Benjamin, former Confederate States attorney general whose short stint as secretary of war ended ingloriously after Roanoke Island fell to the Union, now becomes secretary of state, the cabinet post in which he will serve until May 10, 1865.193

MARCH 23, 1862: As the Army of the Potomac moves into position for its campaign against Richmond, Confederate general Stonewall Jackson puts into motion a plan suggested by Robert E. Lee—a campaign in the Shenandoah Valley intended to draw Union strength away from McClellan’s campaign. Today, Jackson suffers a tactical defeat at the first battle of Kernstown. But the encounter does prove to be a successful diversion, as alarmed Union officials in Washington send troops slated to join McClellan’s force to deal with Jackson instead. Meanwhile, Jackson must cope with a problem that has been plaguing Civil War field commanders on both sides: the lack of accurate maps.194

MARCH 26, 1862: “Soon after we reached camp Gen. [Stonewall] Jackson sent me a message that he wished to see me,” Confederate topographical engineer Jedediah Hotchkiss writes in his journal. “I promptly reported, when he said,… ‘I want you to make me a map of the Valley, from Harper’s [sic] Ferry to Lexington, showing all the points of offence and defence [sic] in those places….’ bidding goodbye to my battalion [I] rode back to Mt. Jackson to secure my outfit so I could get to work on the ‘big job’ entrusted to me.” One of the most accomplished mapmakers in the Confederacy, Hotchkiss had been born in the North, but was a schoolteacher in Staunton, Virginia, when the war began. He will prove to be a singularly valuable asset, as Jackson turns his Shenandoah Valley Campaign into a hallmark in military history. After engaging in a clever ruse (marching half his command out of the valley, then rushing them back via railroad), Jackson will defeat Union forces at the battle of McDowell (May 8), at Front Royal (May 23), in the first battle of Winchester (May 25—a defeat that will cause near panic in some parts of the North), at Cross Keys (June 8), and at Port Republic (June 9). His men will march so often and so far throughout the campaign that they will become known as “Jackson’s Foot Cavalry.” And Jackson himself will emerge from the Shenandoah Valley—eluding converging Union forces sent to defeat him—the foremost hero of the Confederacy.195

The “Carondelet” Running the Gauntlet at Island No. 10. Steel engraving by Samuel Sartain after a drawing by J. Hamilton, n.d.

MARCH 30, 1862: Vincent Colyer, an agent of the Brooklyn YMCA, is appointed superintendent of the poor for the Union Department of North Carolina. He will shortly report: “Upwards of fifty [black] volunteers of the best and most courageous, were kept constantly employed on the perilous but important duty of spies, scouts, and guides…. They frequently went from thirty to three hundred miles within the enemy’s lines… bringing us back important and reliable information.”196

MARCH 31, 1862: As pressure for battlefield manpower intensifies, some Union and Confederate men face a dilemma: either personally or as members of a religious group, they are opposed, as a matter of conscience, to bearing arms. Today, Sydney S. Baxter of the Confederate War Department reports, “I have examined a number of persons… who were arrested at Petersburg…. As all these persons are members in good standing in these [Dunker and Mennonite] churches and bear good characters as citizens and Christians, I cannot doubt the sincerity of their declaration that they left home to avoid the draft of the militia and under the belief… they would be placed in a situation in which they would be compelled to violate their consciences…. I recommend all the persons in the annexed list be discharged on taking the oath of allegiance and agreeing to submit to the laws of Virginia and the Confederate States in all things except taking arms in war.”197

APRIL

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30

Battle of Shiloh April 6th 1862. Color lithograph published by Cosack & Co., 1885.

APRIL 3, 1862: With the campaign beginning against Richmond, and in a surge of optimism after Grant’s victories in the west and the tactical victory over Jackson at Kernstown (see March 23, 1862), U.S. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, believing that current manpower will be enough to bring the war to a successful conclusion, orders all U.S. recruiting offices closed. They will not remain closed for very long.198

APRIL 4, 1862: The Union armored gunboat Carondelet, at night and in a terrific thunderstorm, fights its way past the batteries on Confederate-held Island No. 10, at the heart of a U-shaped dip in the Mississippi River near New Madrid, Missouri. As soon as the war started, Southerners had commenced fortifying the island and nearby river bluffs in order to interrupt Union river traffic. Carondelet’s passage of Island No. 10 is the first step toward cutting off and reducing this island stronghold. (See also April 7, 1862.)199

APRIL 5, 1862: The Army of the Potomac launches the Peninsula Campaign by initiating a siege of Yorktown, Virginia, at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula. McClellan has chosen to besiege rather than attack the town because he considers it too strong a Confederate position to carry with a single frontal assault, estimating at one point that he is facing a force of “not less than 100,000 men.” In fact, Major General John B. Magruder is holding the Confederate defensive line with only seventeen thousand troops—keeping them in motion to give the impression that his force is much more substantial and dotting his line with “Quaker guns” (logs painted black to resemble cannon), which add to the illusion of strength. “I have made my arrangements to fight with my small force,” he reports, “but without the slightest hope of success.”200 (See also May 3, 1862.) In the western theater, a Confederate army is on the march from the important railroad hub of Corinth, Mississippi. Led by Albert Sidney Johnston and P. G. T. Beauregard (who proposed this offensive), the Southern force includes many raw recruits wholly unaccustomed to military discipline and marching in bad weather through rugged terrain. Progress, and stealth, suffer accordingly—so much so that Beauregard urges Johnston to turn back. But the ranking general presses on. His objective: Ulysses S. Grant’s forty-thousand-man army now camped, and awaiting reinforcements, just across the state border, on the Tennessee River. Neither Grant nor his leading division commander, William T. Sherman, is expecting a major Confederate offensive, believing that the Rebels are still recovering from their recent defeats at Forts Henry and Donelson (see February 6, 12, 15, 16, 1862). Perhaps for that reason, Grant has not adequately fortified his position, concentrating instead on training the many green troops in his army.201

APRIL 6, 1862: At dawn, Union patrols probing the area in front of Grant’s main encampment at Shiloh Church near Pittsburg Landing, Tennessee, run into the leading elements of Johnston’s army and manage to bring a last-minute warning to Union lines. Hot on their heels, the vanguard of forty thousand Southern troops slams into the Northern position, beginning the battle of Shiloh. Sherman’s division and that of John A. McClernand take the brunt of the initial assault, but Union forces are hard hit all along their line; some untried Federal units break and run to the rear. Having rushed to the field from his headquarters upriver as soon as the firing started, Grant rallies his troops as he moves from division to division—particularly noting, as the day progresses, the exemplary behavior of an officer who, not long before, some members of the press had labeled “touched in the head” (see October 16, 1861). (“I never deemed it important to stay long with Sherman,” Grant will later report. “[B]y his constant presence… [he] inspired a confidence in [his untried] officers and men that enabled them to render services on that bloody battle-field worthy of the best of veterans.”) Meanwhile, at a sunken road in deep woods, Benjamin Prentiss, leading remnants of his division and elements of others, buys valuable time for the Union, holding firm against repeated assaults in fighting so ferocious that the Confederates dub the area the “Hornet’s Nest” before they overwhelm and capture Prentiss and other survivors. By the end of the day, the Southerners have pushed Union lines more than two miles back toward the river—but they have lost their commander. Albert Sidney Johnston bled to death on the field after a bullet severed an artery, the highest-ranking officer to be killed in the Civil War. Later, under cover of lightning-streaked darkness, a thunderstorm adding to the misery of the torn and exhausted armies, Grant’s reserve moves into the Union line, which is also augmented by the awaited reinforcements led by Don Carlos Buell—a total of twenty-five thousand fresh troops. Confederates, now led by Beauregard, are not reinforced—and suffer more casualties as Union gunboats shell their position through a long and sleepless night.

Fort Pulaski, Mouth of Savannah River, and Tybee Island, Ga. Photographer and date unknown. The strategically placed fort fell to the Union on April 10, 1862, after a fierce artillery battle.

APRIL 7, 1862: Regrouped, reinforced, and now outnumbering the Confederates, Union troops at Shiloh attack and gradually, through hours of brutal combat, regain all their lost ground and force Beauregard to order a retreat to Corinth. “Our condition is horrible,” Southern general Braxton Bragg will write the next day. “Troops utterly disorganized and demoralized. Road almost impassable. No provisions and no forage.” They leave behind them a field littered with dead and wounded and a Union force shaken by the most terrible battle yet seen on the American continent: more than fifty-four hundred men have been killed; more than sixteen thousand are wounded or missing. A precursor to the huge Civil War battles to come, Shiloh is regarded as a Union victory. It is so dearly bought and such a near thing, however, that the recently lionized Grant becomes a magnet for criticism. As he weathers the storm, he also takes away from the battle a sobering lesson, which he will later describe in his memoirs. “Up to the battle of Shiloh I, as well as thousands of other citizens, believed that the rebellion against the Government would collapse suddenly and soon, if a decisive victory could be gained over any of its armies. [After Shiloh], I gave up all idea of saving the Union except by complete conquest.” As Shiloh concludes, the Confederate bastion on Island Number 10 in the Mississippi River falls to Union troops commanded by Major General John Pope, who becomes a new Northern hero.202

APRIL 10, 1862: Near Savannah, Georgia, Federal troops who had established a base on Tybee Island commence firing on Fort Pulaski at the mouth of the Savannah River, a bastion whose defenses had been improved some three months earlier with the help of slave labor. Employing rifled cannon (more accurate and powerful than smoothbore weapons), the Union artillerymen cut a breach in the fort’s formidable walls within five hours. On April 11, after shells penetrate the fort’s magazine, the Confederate commander, Colonel Charles H. Olmstead, will surrender. Without this defensive fortification guarding the city from ocean attack, Savannah is no longer an effective port for Confederate blockade runners.203

APRIL 16, 1862: As bad news continues to come in from the West, and with the Union army less than ten miles from Richmond, the Confederate Congress initiates the first general military draft in American history. This first of three Confederate conscription acts provides that white men between ages eighteen and thirty-five might be drafted for three-year terms or until the end of the war, should that come sooner—and it extends to three years the terms of men already in service who had enlisted for shorter periods. Because the Confederacy is short of arms, the law includes a passage encouraging conscripts and volunteers to bring their own weapons. It also includes two provisions that will prove to be increasingly troublesome: that conscription applies only to men “who are not legally exempted from military service,” and that “persons not liable for duty may be received as substitutes for those who are, under such regulations as may be prescribed by the Secretary of War.”204 In Washington, it is a momentous day. More than ten years before, when he was a representative from Illinois in the Thirtieth Congress, Lincoln had proposed introducing a bill to end slavery in the District of Columbia but could find little support. Today, as president, he signs the sort of bill he had envisioned. The only example of compensated emancipation in the United States, this law provides for a payment of up to $300 to loyal Unionist masters for each slave, for whom they can prove a claim, who is freed by this act—and also authorizes $100,000 for colonization of freedmen. (The Federal government must continue to enforce fugitive slave laws, which are still in force, however; thus, runaways from loyal slave states who are apprehended in Washington must still be returned to their owners.) Abolitionists throughout the North are elated by the law, despite its flaws. “If we rejoice and give thanks to the Almighty for this great boon,” the Anglo-African journal declares, “we rejoice less as black men than as part and parcel of the American people…. We can point to our Capital and say to all nations, ‘it is free!’ Americans abroad can now hold up their heads when interrogated as to what the Federal Government is fighting for, and answer, ‘There, look at our Capital and see what we have fought for.’ ”205

Title page, The Slavery Code of the District of Columbia, 1862, pictured with “Slavery Code of the District of Columbia” manuscript, 1860. The printed Slavery Code was published on March 17, 1862, just one month before President Lincoln signed the law that ended slavery in Washington, DC.

“Our condition is horrible…. Troops utterly disorganized and demoralized. Road almost impassable. No provisions and no forage.”

—GENERAL BRAXTON BRAGG, APRIL 8, 1862

APRIL 18, 1862: Pursuing the Union goal of securing control of the Mississippi River, and thus splitting the Confederacy, David Farragut’s fleet begins five days of mortar bombardment of heavily armed Fort Jackson (seventy-four guns), on the west bank of the Mississippi, and Fort St. Philip (fifty-two guns), on the east bank, below New Orleans.206

APRIL 21, 1862: The Confederate government legitimizes many of the guerrilla organizations already fighting throughout the Confederacy by passing the Partisan Ranger Act, a relatively short and nonspecific piece of legislation that states, in essence:

[T]he President… is hereby authorized to commission such officers as he may deem proper with authority to form bands of partisan rangers, in companies, battalions or regiments…. [They] shall be entitled to the same pay, rations, and quarters… and be subject to the same regulations as other soldiers.

A range of partisan leaders, from former cavalry scout John Singleton Mosby to Missouri “bushwacker” William Clarke Quantrill, will officially enroll their men in the Confederate armed forces under this act. Yet most Union officers, bitterly frustrated by guerrillas and the Southern civilians who support them, will refuse to recognize any partisans as anything other than outlaws, directing their men to “Pursue, strike, and destroy the reptiles.”207

Brigadier General Herman Haupt (1817–1905), USA. Photograph between 1860 and 1865 by the Brady National Photographic Art Gallery. A graduate of West Point (1835), Haupt left the service only a few months after graduation and established a reputation as an engineering and railroad authority before he was called back to the colors in 1862.

This map, published in the New York Herald, April 26, 1862, shows the forts and other defenses standing between Admiral Farragut’s naval squadron and the South’s largest city, a prime target in the Union’s quest to control the entire Mississippi River.

APRIL 22, 1862: Secretary of War Stanton summons civil engineer, author, and inventor Herman Haupt to Washington, where the secretary will appoint Haupt chief of construction and transportation of U.S. military railroads (see also February 11, 1862). Haupt will fulfill the role with admirable efficiency, establishing repair crews that become so adept at rebuilding lines damaged by Confederates that it will be said that “the Yankees can build bridges quicker than the Rebs can burn them down.”208

APRIL 24, 1862: U.S. flag officer David G. Farragut leads his fleet through the gunfire from Forts Jackson and St. Philip below New Orleans in a hair-raising, artillery-punctuated predawn advance that is later described by Bradley Osbon, an officer and newspaper correspondent on Farragut’s flagship, USS Hartford: “We were struck now on all sides. A shell entered our starboard beam, cut our cable, wrecked our armory and exploded at the main hatch, killing one man instantly and wounding several more. Another entered the muzzle of a gun, breaking the lip and killing the sponger who was in the act of ‘ramming home.’ A third entered the boatswain’s room, destroying everything in its path and, exploding, killed a colored servant who was passing powder.” All but three vessels of Farragut’s fleet make it past the forts—stunning news to the people of New Orleans, where alarm bells ring and the Confederate garrison commander, Major General Mansfield Lovell, declares martial law.209

Going Ashore at New Orleans. Engraving published in Letters of George Hamilton Perkins, USN, 1886. Then a twenty-five-year-old lieutenant, Perkins accompanied Captain Theodorus Bailey through this irate crowd to secure the official surrender of the city.

APRIL 25, 1862: Admiral Farragut’s fleet arrives at New Orleans. “Ah me! I see them now as they come slowly round Slaughterhouse Point into full view,” young citizen George Washington Cable will later write, “silent, grim, and terrible; black with men, heavy with deadly portent; the long-banished Stars and Stripes flying against the frowning sky.” As there are fewer than three thousand Confederate troops in the city, far too few to defend it, General Lovell marches them out and declares New Orleans an open city. Laced with smoke from burning stores of cotton and tobacco and the unfinished warship CSS Mississippi, which the Southerners burned so it would not fall into Northern hands, it is also an angry city: “The crowds on the levee howled and screamed with rage,” Cable will remember. “The swarming decks answered never a word; but one old tar on the Hartford, standing with lanyard in hand beside a great pivot-gun, so plain to view that you could see him smile, silently patted its big black breach and blandly grinned.” After the mayor declines the honor of surrendering the city, Farragut’s second in command, Captain Theodorus Bailey, and Lieutenant George H. Perkins walk through a hostile crowd and lower the Louisiana state flag from over city hall, replacing it with the Stars and Stripes—an act that Cable will describe as “one of the bravest deeds I ever saw done.” News that the Confederacy’s largest and most cosmopolitan city has fallen to the Union stuns the people of the South. “No event was considered more unlikely during the whole progress of this war,” Memphis Appeal correspondent John R. Thompson will write on May 8, “than that New Orleans would fall into the hands of the enemy.”210