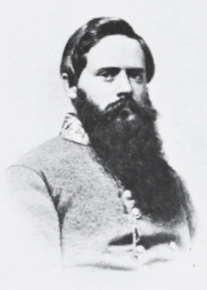

Brigadier General Fitzhugh Lee (1835–1905), CSA.

Confederate States of America bonds. The Confederate government, from the first, relied more on bond issues than unpopular taxes, issuing $15 million in bonds in 1861.

MARCH 16, 1863: Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton sends initial instructions to Samuel Gridley Howe, James McKaye, and Robert Dale Owen, of the newly formed American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission, which is to investigate the condition of slaves and former slaves. They will soon travel south to interview freedmen and Union officers, their work culminating in the creation of the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands in 1865.127

MARCH 17, 1863: “You have got to stop these disgraceful cavalry ‘surprises!’ ” Joe Hooker raged to General William Averell, after a daring penetration of Union lines by General Fitzhugh Lee’s Confederate horsemen. (A taunting note that Lee, a nephew of Robert E., left Averell, his West Point classmate, rubbed salt in the wound: “If you won’t go home, return my visit and bring me a sack of coffee.”) Today, Averell leads twenty-one hundred Union cavalry across the Rappahannock River in pursuit of Lee. In the ensuing five-hour battle at Kelly’s Ford (in which a Confederate hero of Fredericksburg, artillery major John “The Gallant” Pelham, is killed), the Union cavalry, long rated inferior to their Rebel counterparts, prove themselves equal to the Confederates. Afterwards, a jaunty Averell leaves a package with a reply to Lee’s note: “Dear Fitz: Here’s your coffee. Here’s your visit. How do you like it?”128

MARCH 18, 1863: With the South racked by inflation, plagued by shortages, and strapped for funds, the Confederate Congress has authorized borrowing money through the banking house of French financier Emile Erlanger, a deal negotiated by the Confederate commissioner to France, John Slidell (see November 8, 1861). Today, Erlanger extends a loan of three million pounds—backed by Confederate bonds redeemable for Southern cotton, to be delivered within six months of the end of the war. The Erlanger loan renews, for a time, the Confederacy’s ability to conduct business on the Continent.129

MARCH 26, 1863: The Confederate Congress passes the Impressment Act, authorizing local impressment agents to seize black freedmen and private property (including food, clothing, slaves, railroads, horses, and cattle) to supply the army and navy. Impressment had been used earlier by state government and military officials in emergency situations, but, under the new policy, property seizures will be regulated by state boards under the War Department and become a matter of course in maintaining the war effort (military units will still impress goods as needed). Fraught with inequities, impressment will prompt strong public opposition; eight state legislatures will lodge official complaints, deeming the act a violation of states’ rights.130

The Civil War in America: Attack by the Federal Ironclads on the Harbor Defenses of Charleston. Engraving published in the Illustrated London News, May 16, 1863. The scene depicted “demonstrated undoubtedly that the ladies of Charleston had no undue fear for the result of the attack, which, if successful, would place their homes at the mercy of an exasperated foe,” artist-correspondent Frank Vizetelly declared in his written dispatch.

APRIL

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30

The Army of the Potomac Crossing the Rappahannock River on a Pontoon Bridge at Night, Near Rappahannock Station. Drawing by Edwin Forbes, October 1863.

APRIL 2, 1863: At a time when the food rations of the Army of Northern Virginia have been cut by 50 percent, hundreds of distraught citizens gather in the streets of crowded and inflation-ridden Richmond, Virginia—where it takes more than ten times the money to feed a family for a week today than it did just three years ago. Receiving only a platitudinous speech from Governor John Letcher when they mass in front of the Capitol, people go in search of somewhere to vent their anger, sacking stores in the business district as they storm through the city. Police and militia finally end the violence, arresting some forty-four women and twenty-nine men out of a mob of over a thousand. Amid rumors of another planned food uprising, cannons are placed in the business district, and troops slated to reinforce General Longstreet are kept in the city. Other towns across the Confederate States suffer similar disturbances as prices skyrocket and civilian food supplies dwindle.131

APRIL 7, 1863: A Union flotilla of nine ironclad vessels, captained by handpicked officers and led by Flag Officer Samuel Du Pont, sails into the Charleston, South Carolina, harbor. Du Pont plans to reduce Fort Sumter by smashing its weakest walls and then sail past the fort to the city, but the Charleston defenses prove formidable. “The fires of hell were turned upon the Union fleet,” Du Pont’s chief of staff, Christopher Rodgers, will later report. “The air seemed full of heavy shot, and as they flew they could be seen as plainly as a base-ball in one of our games.” Despite their armor, the Union ships take a terrible beating; USS Keokuk, which Rodgers will remember being “riddled like a colander,” will sink the next day. The expedition is proof positive that Charleston cannot be taken by naval forces alone.132

APRIL 10, 1863: Within a long state-of-the-Confederacy speech to the Southern people, President Davis addresses a subject that has caused much recent civilian unrest (see April 2, 1863):

The very unfavorable season, the protracted droughts of last year, reduced the harvests on which we depended far below an average yield…. If through a confidence in early peace, which may prove delusive, our fields should be now devoted to the production of cotton and tobacco instead of grain and live stock, and other articles necessary for the subsistence of the people and the Army, the consequences may prove serious, if not disastrous…. Let fields be devoted exclusively to the production of corn, oats, beans, peas, potatoes, and other food for man and beast.133

APRIL 13, 1863: Now commanding the Department of the Ohio and concerned about the activities of Peace Democrats in his command, General Ambrose Burnside issues General Order No. 38: “The habit of declaring sympathy for the enemy will not be allowed in this department. Persons committing such offenses will be at once arrested with a view of being tried… or sent beyond our lines into the lines of their friends. It must be understood that treason, expressed or implied, will not be tolerated in this department.” Ohio’s leading Peace Democrat, Clement L. Vallandigham, opposed to the war from its beginning and now a candidate for governor of the state, will react to the order as a bull might react to a red flag (see May 1, 7, 1863).134

APRIL 15, 1863: “Uncle Abe and Mrs. Abe were down, lately,” Chaplain A. M. Stewart writes to his home-front readers from his army encampment, “and, what showings off were here and there!”—including the “mighty host” of the reorganized and reinvigorated Army of the Potomac passing in review before the president and General Joseph Hooker. Behind the scenes, another sort of review was going on: sometime during the Lincolns’ visit (April 6–11), the president gave Hooker a memorandum on the general’s planned campaign against Richmond. “My opinion is, that just now, with the enemy directly ahead of us, there is no eligible route for us into Richmond…. Hence our prime object is the enemies’ army in front of us,… we should continually harass and menace him, so that he shall have no leisure, nor safety in sending away detachments. If he weakens himself, then pitch into him.”135

Review by the President of the Cavalry of the Army of the Potomac. Pencil, brown wash, and Chinese white drawing by Alfred R. Waud, April 9, 1863. “You can get some idea of the number of troops reviewed when I tell you that, for nearly two hours, they were passing steadily in solid column,” Captain Charles F. Morse wrote home a few days later. “In the center opposite the troops, looking sick and worn out, dressed in a plain black suit with the tallest of stove-pipe hats, was the President, seated on a fine horse with rich trimmings.”

APRIL 16, 1863: Vicksburg citizens celebrating the impregnability of their “Gibraltar of the West” at a gala ball are alarmed by the sound of artillery as Captain David D. Porter leads a flotilla of twelve Union vessels past the city’s formidable defenses. Protected by gunboats, the transport vessels in the flotilla bear the first of General Grant’s army to pass Vicksburg on their way to establishing a base to its south, as Grant launches his second campaign to take the city.136

APRIL 17, 1863: Leading seventeen hundred Union cavalrymen, Colonel Benjamin H. Grierson embarks on a spectacular two-week, six-hundred-mile raid through Mississippi, during which the Federals tear up railroads, take captives, and divert attention and Confederate manpower from impeding Grant’s operations around Vicksburg.137

APRIL 19, 1863: “I do not think our enemies are so confident of success as they used to be,” Robert E. Lee writes to his wife. “If we can ba∆e them in their various designs this year & our people are true to our cause & not so devoted to themselves & their own aggrandizement…. next fall [after the U.S. presidential election] there will be a great change in public opinion at the North. The Republicans will be destroyed & I think the friends of peace will become so strong as that the next administration will go in on that basis. We have only therefore to resist manfully… [and] our success will be certain.”138

APRIL 24, 1863: Struggling under runaway inflation, the Confederate government imposes a comprehensive tax law, including a progressive income tax, excise and license duties, and a 10 percent profits tax. A 10 percent “tax in kind” on agricultural produce is bitterly resented by farmers who are already subject to impressment of needed goods by Confederate commissary and quartermaster officers (see March 26, 1863). In Washington, President Lincoln issues General Order No. 100, Instructions for the Government of Armies of the United States in the Field. Generally known as the Lieber Code, after its principal author, German-American political philosopher Francis Lieber (1789–1872; see February 16, 1862, and February 14, 1863), these instructions represent the first attempt to codify the international law of war. Among its many provisions, the code includes a statement that reflects the changing nature of the war, and of U.S. armed forces: “The law of nations shows no distinction of color, and if an enemy of the United States should enslave and sell any captured persons of their Army, it would be a case for the severest retaliation, if not redress.”139

APRIL 27, 1863: “Gen. Hooker has certainly performed wonders, during his brief command,” Chaplain A. M. Stewart wrote, to his home newspaper, earlier this month. “The army, when he took it, was defeated, discouraged… and… demoralized. The contrast is now remarkable…. the soldiers seem universally to have the fullest confidence in Gen. Hooker, and, also, in themselves…. What the result will be, time and coming events will unfold. Gen. Hooker has not, as yet… conducted an active campaign.” Today, Hooker begins to move against Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.140

Colonel Grierson, Sixth Illinois Cavalry. Wood engraving published as the cover illustration of Harper’s Weekly, June 6, 1863. For his leadership on the successful April–May raid, which diverted the Confederates and demonstrated that Union troops could operate without a supply line, Benjamin H. Grierson (1826–1911) was promoted to brigadier general.

APRIL 29, 1863: “The enemy crossed the Rappahannock today in large numbers,” Robert E. Lee wires President Davis, from his headquarters at Fredericksburg, Virginia. “Their intention I presume is to turn our left & probably to get into our rear. Our scattered condition favors their operations. I hope if any reinforcements can be sent they may be forwarded immediately.” This evening, Fighting Joe Hooker joins the three Union army corps that have crossed the river at their camp near the large house owned by the Chancellor family in an area known, for good reason, as the Wilderness. Armed with more accurate information on his enemy than previous Army of the Potomac commanders have enjoyed, aware that his forces outnumber Lee’s and that Lee’s are scattered, Hooker still has the air of confidence that led him, days earlier, to say to some of his officers: “My plans are perfect, and when I start to carry them out, may God have mercy on General Lee, for I will have none.”141