JULY 1, 1863: A limited engagement between Major General Henry Heth’s division of A. P. Hill’s Confederates and John Buford’s dismounted Union cavalry begins the three-day battle of Gettysburg. As Buford’s men delay the Southerners’ progress, General John Reynolds arrives, sends men to hold McPherson’s ridge west of the town, and, shouting “Forward men, forward, for God’s sake,” leads a Wisconsin regiment to clear nearby Herbst woods, where Confederate riflemen who are “howling like demons” meet the assault with deadly volleys that mortally wound the general. Bitter fighting temporarily secures McPherson’s ridge for the Union. But after a mid-afternoon lull (as Robert E. Lee arrives and more troops of both sides converge on the battlefield), the Confederates renew their assault, igniting combat so intense one Union lieutenant will remember men falling around him “like ripe apples in a storm.” Retreating through the town, the Union troops regroup to its south, by late that evening forming part of what will eventually be a fishhook-shaped line along Cemetery Ridge embracing places that will soon become legendary: Cemetery Hill, Big and Little Round Top, and Culp’s Hill. In the evening, as General Meade arrives on one side of the battlefield, on the other, Robert E. Lee determines to renew the battle the following day, “in view of the valuable results that would ensue from the defeat of the army of General Meade.” In Vicksburg, General John Pemberton sends a message to each of his four division commanders: “Unless the siege of Vicksburg is raised, or supplies are thrown in, it will become necessary very shortly to evacuate the place…. You are, therefore, requested to inform me… as to the condition of your troops and their ability… to accomplish a successful evacuation.” The division commanders report that evacuation will not be possible; two of the generals advise Pemberton to surrender.39

JULY 2, 1863: Leading twenty-five hundred Confederate cavalrymen, Brigadier General John Hunt Morgan begins the longest cavalry raid of the war, impelled by his conviction that only by taking the war into the Northern homeland, and thus augmenting the influence of Union Copperheads, could pressure on the Confederacy be relieved. During twenty-five days of almost constant combat, covering more than seven hundred miles (through Kentucky, southeast Indiana, and southern and eastern Ohio), Morgan and his “Terrible Men” will make no distinction between enemies and potential allies as they hold businesses for ransom; destroy commercial buildings, railroads, and bridges; loot local treasures—and garner the undying enmity of the Northerners in their path. They will also divert some 14,000 Federal troops from other duties and spark the call-up of 120,000 militia before Union troops under Brigadier General Edward H. Hobson hand them a costly defeat at Buffington Island (Morgan’s troops suffer 850 casualties plus 700 men captured). Finally captured with his remaining 364 men less than 100 miles from Cleveland, Morgan will be sent to the Ohio state penitentiary—but that will not end his Civil War story (see November 27, 1863, and September 4, 1864). At Gettysburg, despite objections from Lieutenant General James Longstreet (who favors a turning movement), Lee orders an attack against the left of the Federal line, which begins, under Longstreet’s command, at about 4:00 PM. Through air sizzling with musket and rifle fire, over ground erupting from exploding artillery shells, Confederate and Union forces grapple in what one Texan will term “a devil’s carnival.” Bloody struggles engulf new battlefield landmarks: the Wheatfield, the Devil’s Den, and the Peach Orchard. College professor Joshua Chamberlain, now colonel of the Twentieth Maine, leads a bayonet charge to repulse Confederates charging Little Round Top after his men run out of ammunition. On Culp’s Hill, five thousand screaming Confederates repeatedly smash up against field fortifications painstakingly erected by fourteen hundred Union defenders led by sixty-two-year-old George S. Greene. Finally, the firing subsides. Both armies have suffered terribly; neither has gained an appreciable advantage. The night air fills with the odor of death, an eerie hum from moaning wounded—and, from behind Federal lines, band music played to mask screams from the Union hospitals. Ghostlike figures walk the battlefield searching for comrades. At their respective headquarters, Meade decides to maintain a defensive position, while Lee determines to renew his attack the next day.40

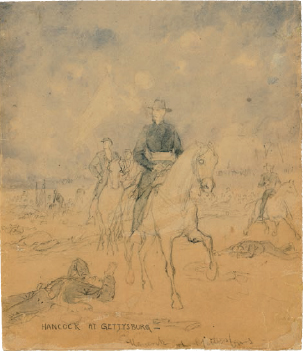

Hancock at Gettysburg. Pencil and watercolor drawing by Alfred R. Waud, ca. July 1–3, 1863. A Union hero of the battle, Major General Winfield Scott Hancock (1824–1886) was instrumental in selecting excellent Union positions on day one, led the successful stand that thwarted Lee’s attempt to turn the Union left flank on day two, and was wounded (but refused to leave the field) as his men withstood Pickett’s Charge on day three.

The Story of Gettysburg. Watercolor over graphite design for a sheet-music cover by James Fuller Queen, ca. 1863. The pivotal three-day battle of Gettysburg would yield endless stories of the suffering and valor of men on both sides. Though it was a Union victory that caused Lee to retreat, as Union officer Charles Francis Adams Jr. noted in a letter on July 12, Lee “has lots of fight left and this war is not over yet.”

JULY 3, 1863: In Richmond, Confederate vice president Alexander H. Stephens boards a boat bearing a flag of truce and sails toward the Union lines around Norfolk. Bearing letters from Jefferson Davis to Abraham Lincoln, and acting with full approval of Davis and the Confederate cabinet, Stephens hopes to exploit Grant’s failure to take Vicksburg and Lee’s daring incursion into the North by bringing peace proposals to the Union leader, whom he has known since they served together in the U.S. Congress. In Mississippi, Confederate general John Pemberton emerges from Vicksburg under a flag of truce. Near a stunted oak tree a few hundred feet from the Confederate lines, he confers with General Grant, an old friend from their service together in the Mexican War. Grant reiterates his demand, made in an earlier message, that the Confederates surrender unconditionally; Pemberton is reluctant. After the interview ends, negotiations continue, via letter, until late into the night. At Gettysburg, Union artillery fire rips into Confederate positions at the base of Culp’s Hill, beginning a seven-hour struggle for that position, the Southerners’ repeated attempts to gain the heights leaving the hillside slippery with blood. To the east of the main battlefield, Union cavalry led by Brigadier General George A. Custer and Colonel John B. McIntosh repulse Jeb Stuart’s formidable horsemen. At the same time, a terrible drama unfolds at the center of the Union line, where Lee has decided to make a frontal assault that will live in memory as Pickett’s Charge. Preceded by forty-five minutes of soul-shattering cannon fire (which falls far short of ravaging Union artillery batteries, as Lee believes it will), the assault begins with 13,500 Confederates, in line, battle flags flying, moving forward—until their order disintegrates under volleys of furious Union fire. “Come on, Come to Death,” some Federals shout, and despite fearful losses, the Rebels press on until the survivors can endure it no longer. Many are taken prisoner; many others stream back toward the Confederate lines on Seminary Ridge—where Robert E. Lee tells them, “It was not your fault this time. It was all mine.” From Union lines on Cemetery Ridge, “cheer upon cheer arose from our troops,” staff officer Adolphus Cavada will recall, “and spread right & left like wild fire.”41

The Battle of Gettysburg. Engraving by John Sartain (1808–1897), after a painting by Peter Frederick Rothermel (1812–1895), ca. 1872. The scene depicted in Rothermel’s painting may be Pickett’s Charge.

JULY 4, 1863: Exhausted troops and overwhelmed medical workers survey the carnage at Gettysburg: over the past three days some fifty-one thousand men of both sides have been killed, wounded, or gone missing. “[E]verywhere wounded men were lying in the streets on heaps of blood-stained straw,” Union nurse Sophronia Bucklin will write about her arrival after the battle, “everywhere there was hurry and confusion, while soldiers were groaning and suffering.” As evening descends and rain, falling since midday, grows heavier, Lee’s army withdraws from the battlefield, miles of marching men, their wounded and supplies in wagons, struggling along miry roads. By then, President Lincoln has announced to the country that “news from the Army of the Potomac… is such as to cover that Army with the highest honor, [and] to promise a great success to the cause of the Union.” As more details of the battle circulate, the surge in Northern morale is reflected in ecstatic newspaper headlines, including the Philadelphia Inquirer’s “Victory! Waterloo Eclipsed!” In Mississippi, John Pemberton and his Confederate garrison march out of Vicksburg, stack their arms, and surrender to Ulysses S. Grant and the Federal army that has had Vicksburg in its sights for nearly a year. Securing the city is so important a victory that General Grant will later write in his memoirs, “The fate of the Confederacy was sealed when Vicksburg fell.” His commander in chief also appreciates the magnitude of the western army’s achievements—and the quality of its commander. “Grant is my man,” President Lincoln will state on July 5, “and I am his the rest of the war.” In Washington, after a cabinet discussion of Alexander Stephens’s proposed visit to Washington (see July 3, 1863), and with good news from Gettysburg in hand, Lincoln denies the Confederate vice president’s request for a pass through Union lines to meet with Lincoln in Washington. In New York City, New York’s Democratic governor, Horatio Seymour, gives a fiery speech at an antidraft rally. Dismissing the Lincoln administration’s claim of military necessity for emancipation and conscription, Seymour thunders, “Remember this—that the bloody and treasonable doctrine of public necessity can be proclaimed by a mob as well as by a government.”42

The American Ram. Lithograph cover by H. F. Greene for a patriotic song by R. S. Frary, published by Henry Tolman & Co., 1863. A celebration of the long-awaited victories at Vicksburg and Port Hudson, which brought the entire Mississippi River under Union control, the song is dedicated to U.S. Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, who was responsible for ushering the Union navy into the age of ironclad steamers.

Civil War induction officer with a draft lottery box. Sixth-plate ambrotype, ca. 1863.

JULY 9, 1863: With Vicksburg now in Union hands, the Confederates 240 miles to the south at Port Hudson, recognizing that their situation is hopeless, surrender this last Southern bastion on the Mississippi River. “The father of waters again goes unvexed to the sea,” President Lincoln will declare. The Confederacy is split in two.43

JULY 10, 1863: Beginning another attempt to take Charleston, South Carolina (see April 7, 1863), Union infantry under Brigadier General George Crockett Strong, supported by naval guns and Union artillery on Folly Island, land on the south end of Morris Island, at the mouth of Charleston Harbor. Their objective: Fort (Battery) Wagner, one of the harbor’s main defenses. Their first assault on the fort, July 11, will be unsuccessful. Within a week, with considerable reinforcements, they will try again (see July 18, 1863).44

JULY 11, 1863: Draft officers begin drawing names in heavily Democratic New York City, where sentiment against abolition and conscription runs high. This is especially the case among hardscrabble Irish workers already struggling against lagging wages and confined with their families in seething tenements that are seedbeds of crime and disease. Many Irishmen are still boiling with resentment at being replaced by black stevedores during a bitter longshoremen’s strike in June, and they worry about the same thing happening if they are drafted: at this time, black men are not considered citizens and thus are not eligible for the draft. Moreover, the three-hundred-dollar fee the government requires for legally evading the draft is, for the vast majority of Irish laborers, an impossible amount to raise. Today’s lottery goes smoothly—but the following day, a Sunday, crowds of angry people, some of them fueled by cheap liquor and all of them now aware that the state’s Democratic administration cannot protect New York from the draft, will plot to stop the drawings.45

JULY 13, 1863: President Lincoln composes a note to Ulysses S. Grant, “as a grateful acknowledgement for the almost inestimable service you have done the country.” He goes on to make a small confession: “When you got below, and took Port-Gibson, Grand Gulf, and vicinity, I thought you should go down the river and join Gen. [Nathaniel] Banks; and when you turned Northward East of the Big Black [River], I feared it was a mistake. I now wish to make the personal acknowledgment that you were right, and I was wrong.”46

JULY 13–17, 1863: New York erupts into four of the bloodiest days of mob violence in United States history, an uprising that begins with thousands of people forgoing work to demonstrate outside the draft office on Third Avenue. Someone hurls a stone through an office window, someone else fires a pistol, and the demonstration transforms to a riot—initially led by members of a company of firemen, one of whom has just been drafted. Surging into the office, the rioters smash everything inside, the draft officials barely escaping with their lives as the mob sets fire to the building (imperiling hundreds of people who live on the floors above). Outside, as the firemen watch the building burn, rioters cut telegraph wires and attack the small force of police and soldiers that city authorities can muster to stop them (most city-based regiments are still with the Army of the Potomac in Pennsylvania). The mob’s fury builds and widens to include Republicans, soldiers, the wealthy, and, especially, black people and the businesses that employ them. “One of the first victims to the insane fury of the rioters,” Harper’s Weekly will report, “was a negro cartman residing in Carmine Street,” who is beaten, hanged, and set afire. Colonel Henry F. O’Brien of the Eleventh New York Infantry is another victim, beaten, shot, and pummeled with stones as he is dragged through the streets before he finally dies. The mob attacks the headquarters of the New York Times (where they are turned away by borrowed Gatling guns); besiege Horace Greeley in the Tribune offices, setting the first floor afire; and loot and burn the four-story Colored Orphan Asylum (its staff and 233 children escaping to safety) before troops fresh from the carnage at Gettysburg arrive in the city and help restore order. The draft is temporarily suspended in New York City as the government sends more troops and the human cost of the violence becomes clear: hundreds have been injured; at least 105 people—including eleven African Americans, eight soldiers, two police officers, and dozens of rioters—have been killed.47

The Riots in New York: The Mob Lynching a Negro in Clarkson-Street. Engraving published in the Illustrated London News, August 8, 1863. “[A] stout clothes-line… was attached to the negro’s neck,” the correspondent from the News reported, “and he was drawn up several feet. Some of them then set his shirt on fire, and the sight presented was a frightful one. The body remained hanging, surrounded by a dense crowd of people, who shouted and yelled, pursuing every negro who made his appearance.”

The Sinking of the Japanese Ships. Wood engraving based on a drawing by W. Taber, published in The Century Illustrated Monthly magazine, April 1892. Occurring only three years after the first visit of Japanese diplomats to Washington, DC, the U.S. Navy’s defeat of attacking Japanese vessels in the Shimonoseki Straits strained relations between the two countries at a time when the war at home required most of the government’s, and the navy’s, attention.

JULY 16, 1863: In the Straits of Shimonoseki, Japan, USS Wyoming, on patrol against Confederate commerce raiders, emerges victorious from a battle with the makeshift fleet of a Japanese warlord who is intent on driving foreigners from those well-traveled waters. This marks the first U.S. naval engagement with Japanese forces since Commodore Matthew Perry and his warships were instrumental in opening Japan to American and European vessels in 1854. The situation will remain volatile: “Our relations with Japan have been brought into serious jeopardy,” President Lincoln will state in his December message to Congress, “through the perverse opposition of the hereditary aristocracy of the empire, to the enlightened and liberal policy of the Tycoon designed to bring the country into the society of nations. It is hoped, although not with entire confidence, that these difficulties may be peacefully overcome.”48

JULY 18, 1863: Six thousand Union troops commanded by Brigadier General Truman Seymour make a frontal assault on the formidable Fort Wagner at Morris Island in Charleston Harbor (see July 10, 1863). In the vanguard of the attack is the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts, an African American infantry regiment that had arrived on the island earlier in the day. Surging forward through withering fire that includes shells from nearby Confederate batteries and rifle fire that sweeps them at times from three sides, the regiment manages to seize one small angle of the fort. But the hold is tenuous, and the cost is too great. “Men fell all around me,” Frederick Douglass’s son Lewis will write to his future wife, Amelia. “A shell would explode and clear a space of twenty feet, our men would close up again, but it was no use.” Taking more casualties, the Fifty-fourth is forced to fall back, and the Union assault fails. Later, when Union men, under a flag of truce, attempt to retrieve the body of Colonel Robert Gould Shaw, the regiment’s white commanding officer, they are reportedly told by a Confederate, “We have buried him with his niggers!” Intended as an insult, this will become a rallying cry in the North, where the Fifty-fourth’s valor will be widely celebrated. “This regiment has established its reputation as a fighting regiment,” Lewis Douglass will write. “I wish we had a hundred thousand colored troops we would put an end to this war.”49

Colonel Robert G. Shaw (1837–1863), USA. Upon learning that the U.S. Army was attempting to retrieve Shaw’s body from the common grave Confederates had made for him and his soldiers, Shaw’s father asked that the colonel’s body remain with those of his men.

Sergeant William H. Carney (1840–1908), USA. Reproduction of a photograph, ca. 1900, published in Deeds of Valor: How Our Soldier-Heroes Won the Medal of Honor, 1901. Carney earned his Medal of Honor at Fort Wagner, where he rescued the Union colors in the midst of a hail of bullets, proudly telling fellow survivors of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts, “Boys, the old flag never touched the ground.”

Louisa May Alcott (1832–1888). Photo-gravure print by A. W. Elson & Co., reproduced in Louisa May Alcott, Her Life, Letters, and Journals, 1889. Alcott’s six weeks as a volunteer nurse in Washington ended when she contracted typhoid fever, which permanently weakened her health.

JULY 30, 1863: Grappling with the problem of how to ensure the safety of black soldiers and their white officers captured by Confederate forces, President Lincoln states an eye-for-an-eye policy: “The government of the United States will give the same protection to all its soldiers, and if the enemy shall sell or enslave anyone because of his color, the offense shall be punished by retaliation upon the enemy’s prisoners in our possession. It is therefore ordered that for every soldier of the United States killed in violation of the laws of war, a rebel soldier shall be executed; and for every one enslaved by the enemy or sold into slavery, a rebel soldier shall be placed at hard labor on the public works.” Unacceptable to many, and impractical to enforce, the policy will fade from view. The problem will remain.50

AUGUST

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

Mail was crucially important to the people of both sides, but in the Confederate States, paper was among the materials not to be wasted. Thus, at times, to make the most of each sheet, correspondents would first write north-to-south, then turn the paper and continue writing west-to-east. As can be seen in this example from the papers of Burton Harrison, secretary to Jefferson Davis, deciphering the result took a high degree of concentration.

AUGUST 8, 1863: In a letter to the editor of the Floridian & Journal, Confederate congressman Robert Hilton defends the Southern government’s less popular wartime measures, particularly suspension of habeas corpus. Even though the president and military authorities “have been compelled for the defense of all that men hold dear—our wives, our homes, our children, our altars—to place temporary restraint at periods of great danger, upon the inhabitants of certain localities,” he writes, “the sufferers, if good citizens, will not complain; if disloyal to our cause, who shall sympathize with them?”51

AUGUST 10, 1863: Meeting with President Lincoln, Frederick Douglass vehemently protests the disparity of pay between white and black soldiers—a policy only recently instituted in violation of assurances originally made to potential African American recruits (see June 4, 1863, August 25, 1862). The president responds, Douglass will report in a postwar autobiography, that in view of the prevailing racial prejudice, “the fact that they were not to receive the same pay as white soldiers seemed a necessary concession to smooth the way to their employment at all as soldiers, but that ultimately they would receive the same.” Given past promises, and the needs of their families, “ultimately” is not a satisfactory time frame for most United States Colored Troops (USCT).52

This selection of Confederate tracts and prayer books reflects the importance of religion in the lives of both Confederate and Union soldiers. Religious revivals occurred in the camps of both armies in 1863 and 1864.

AUGUST 14, 1863: In Missouri, from the 1850s the scene of particularly vicious guerrilla warfare that sharply escalated with the declaration of war, another tragic chapter begins with a terrible accident: five women, the wives and sisters of men fighting under Confederate guerrilla William Quantrill, are killed in the collapse of a Kansas City building in which Union authorities have confined them for aiding the enemy. Enraged, scattered guerrilla bands begin to come together; Quantrill, future postwar outlaws Cole Younger and Frank James, and more than four hundred others determine to exact vengeance for the deaths.53

AUGUST 19, 1863: With six thousand Federal troops now on hand, the draft—suspended after the July riots—resumes in New York City.54

AUGUST 21, 1863: “This is a fast day, proclaimed by the President of the Confederate States, and has been observed as a Sabbath in the Camp,” Army of Northern Virginia mapmaker Jedediah Hotchkiss writes in his diary. “Mr. Lacy preached at our headquarters and nearly a thousand soldiers and many officers came to hear him…. [He] gave us a noble discourse in which he handled, unsparingly, our sins as an army and people, but held out that God must be on our side because we are in the right as proven by our deeds, and our enemies had shown themselves cruel and blood-thirsty…. General Lee, I noticed, spoke to each lady there and to all the children.” In the North, this month, Louisa May Alcott, previously a writer of undistinguished fairy tales, gothic sagas, and short stories, establishes her literary reputation with the publication of Hospital Sketches, a 102-page fictionalized account of the six weeks she served as a nurse in a Washington hospital, until illness forced her to leave. “There they were! ‘our brave boys,’ as the papers justly call them, for cowards could hardly have been so riddled with shot and shell, so torn and shattered, nor have borne suffering for which we have no name, with an uncomplaining fortitude,” one passage reads. “The sight of several stretchers, each with its legless, armless, or desperately wounded occupant, entering my ward, admonished me that I was there to work, not to wonder or weep; so I corked up my feelings, and returned to the path of duty, which was rather ‘a hard road to travel’ just then.”55

AUGUST 21–22, 1863: Issuing orders to “kill every male and burn every house,” William Quantrill leads a force of 450 Confederate guerrillas in an attack on the prewar free-soil bastion of Lawrence, Kansas, where they murder more than 180 men and burn 185 buildings before moving back into Missouri, hotly pursued by Union cavalry. This act of vengeance (see August 14, 1863) will beget reciprocal vengeance. The raid so enrages the area’s Union commander, General Thomas Ewing, that on August 25 he will issue General Orders, No. 11, under which Union forces will sweep four western Missouri counties clear of all but the most certainly loyal inhabitants, turning more than ten thousand suspected Confederate sympathizers out on the roads, with only the goods they can carry, as the smoke from their own burning houses rises behind them. The bitterness this Federal action inspires will last long after the war.56

The Destruction of the City of Lawrence, Kansas, and the Massacre of Its Inhabitants by the Rebel Guerrillas, August 21, 1863. Wood engraving published in Harper’s Weekly, September 5, 1863.

AUGUST 29, 1863: The third of the Confederacy’s experimental submarines, H. L. Hunley (named after the government businessman and inventor who is financing its development), sinks in Charleston Harbor when it is swamped by the wake of a passing vessel as it maneuvers on the surface with an open hatch. Five crewmen are lost; three survive. Unlike its two predecessors, however, Hunley will be recovered, and the South will continue trying to develop it as a combat vessel.57

AUGUST 30, 1863: “Oh these vexatious postal delays,” Union soldier David Lane complains, in his diary, after receiving a letter dated more than two weeks before. “They are the bane of my life. I wonder if postmasters are human beings, with live hearts inside their jackets, beating in sympathetic unison with other hearts.” Mail is vital, to Lane and to hundreds of thousands of other soldiers, North and South: it bolsters courage and brings the reassurance of familiar “voices” to men fighting their way through dangerous and unfamiliar ground. No news can be worrisome, particularly for Confederate soldiers whose families are in the line of Union advance. “Why don’t some one from home write to me?” Lieutenant James Billingslea Mitchell will write his mother in October. “I have not received a line since I left Chattanooga. I am beginning to fear the Yankees have come up from Florida & there has been a battle at home, as there seems to be a perfect cessation of all communication. You must not forget that I am always as anxious to hear from home as you are to hear from me.”58

SEPTEMBER

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30

John Clem: A Drummer Boy of 12 Years of Age Who Shot a Rebel Colonel upon the Battle Field of Chickamauga, Ga., Sept. 20, 1863, from the series Album Sketches of the Great Southern Campaign. Color lithograph based on a drawing by James Fuller Queen, ca. 1863. Nine years old when he was allowed to tag along with the Twenty-second Michigan regiment in 1861, Clem was first mentioned in news reports as “Johnny Shiloh” after that 1862 battle before his fame increased in 1863 as “the drummer boy of Chickamauga.” Eventually a career army man, he retired as a general in 1915.

SEPTEMBER 2, 1863: As Union forces under General William Rosecrans move toward strategically important Chattanooga, Tennessee, crossroads of the only rail lines still linking the eastern and western parts of the Confederacy, Ambrose Burnside’s Union Army of the Ohio occupies Knoxville, which has been evacuated by the Confederates (the division that had occupied the town heading toward Chattanooga to join Braxton Bragg).59

Army Mail Leaving Hd. Qts. Post Office. Army Potomac. Pencil and Chinese white drawing by Alfred R. Waud, ca. March 1863. “We are only a mile and a half from the steamboat landing,” Army of the Potomac lieutenant colonel Alfred B. McCalmont wrote his brother in February 1863, “but our letters go first to Brigade Headquarters, then to Division Headquarters, one mile due west; then to Corps Headquarters, three miles further west; then to Grand Division Headquarters… and finally to the Headquarters of the Army of the Potomac… [after which] they are sent down to Falmouth and thence by rail over to the Potomac river from which they started…. There is a great deal more of method for the sake of method in the army, than of method for the sake of substance.”

SEPTEMBER 5, 1863: United States ambassador to Great Britain Charles Francis Adams writes a stern warning to the British foreign minister, Lord John Russell, on the subject of what have come to be called the Laird Rams—two powerful vessels equipped with subsurface iron extensions designed to pierce the hulls of enemy vessels below the line of their iron plating. Built by the British company John Laird & Sons, the rams were contracted for by James D. Bulloch, the South’s naval agent in England, and are slated to become potent new weapons in the North/South naval war. British law officers, however, have been claiming they have no evidence that the ships are being built for the Confederacy and thus cannot seize them as violations of British neutrality. Adams knows better. However, he does not know that, two days earlier, Lord Russell decided to have British authorities seize the two vessels, thus avoiding a diplomatic crisis with the United States. The rams will eventually be commissioned in the British navy.60

SEPTEMBER 6, 1863: In South Carolina, Confederates vacate Fort Wagner after intensive naval bombardment and in anticipation of an imminent infantry assault. The first Union regiment to move into the fortification will be the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts, the African American regiment that was severely battered leading the unsuccessful Union attack on the fort almost two months earlier (see July 18, 1863).61

SEPTEMBER 8, 1863: As the Confederate division that recently evacuated Knoxville arrives in Chattanooga, joining more than ten thousand other reinforcements that have arrived from Mississippi, Braxton Bragg, leery of becoming trapped should William Rosecrans’s approaching Federals secure the surrounding mountains, leads the Rebel force out of the city. After Union troops occupy Chattanooga the following day, a despondent President Davis will declare, “We are now at the darkest hour of our political existence.” At Sabine Pass on the Texas-Louisiana border, Confederates employing deadly accurate artillery fire hand an embarrassing defeat to a Union expedition (four gunboats escorting seven troop transports) attempting to overwhelm the Southerners’ small fort. Though a minor victory, the action provides a great morale boost to Confederates; President Davis will later refer to it as the “Thermopylae of the Civil War.”62

SEPTEMBER 9, 1863: A brigade of Confederate soldiers plunders the offices, in Raleigh, of the North Carolina Standard, published by William H. Holden, whom many Confederates now regard as a traitor. Holden has reached the conclusion that the South cannot win the war and has been acting on that assumption—organizing antiwar meetings and printing editorials advocating a negotiated peace with the North. At Charleston, South Carolina, United States Marines and sailors attempt a night landing at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor and are turned back with heavy casualties. The attempt fails, in part, because Confederates, using a codebook recovered from USS Keokuk, wrecked during the navy’s earlier assault on Charleston (see April 7, 1863), are able to read flag signals between the Union commanders during the operation’s planning. In Virginia, President Davis overrides the objections of Robert E. Lee and sends General James Longstreet and two Army of Northern Virginia divisions to reinforce Bragg near Chattanooga. Because Union forces now hold the rail hub of Knoxville, these twelve thousand reinforcements will have to take a roundabout route; about six thousand will arrive in time to join Bragg’s army in a bitter fight with the Federals (see September 19–20, 1863).63

Longstreet’s Soldiers Debarking from the Trains Below Ringgold, September 18, 1863. Reproduction of a drawing by Alfred R. Waud, published in The Mountain Campaigns in Georgia by Joseph M. Brown, 1886. Dispatched over General Lee’s objections, Longstreet’s soldiers were to play a crucial role in the battle of Chickamauga.

The First Gun at Chickamauga. Pencil, Chinese white, and black ink wash drawing on tan paper by Alfred R. Waud, ca. September 18, 1863. After searching for each other for some time, by September 18, 1863, Bragg’s Confederates and Rosecrans’s Federals were firing preliminary salvos to what would be the bloodiest battle of the war in the western theater.

SEPTEMBER 10, 1863: Little Rock, Arkansas, falls to the Union, a loss that severely threatens the entire Confederate Trans-Mississippi Department, already cut off from the rest of the Confederacy by the fall of Vicksburg and Port Hudson. The Confederate state government that withdraws from the city with Rebel forces today will reestablish itself in the city of Washington, to the southwest. Unionist Arkansans will establish their own state government early in 1864. These two opposing governments will hold sway over different sections of the state (divided roughly by the Arkansas River) for the remainder of the war—one factor that will contribute to an upsurge in Arkansas guerrilla warfare. In Raleigh, North Carolina, supporters of newspaper editor and prominent state political leader William H. Holden, whose newspaper offices were wrecked by Confederate troops the previous day (see September 9, 1863), return the “favor” by trashing the offices of the local pro-administration newspaper.64

SEPTEMBER 12, 1863: As three scattered columns of William Rosecrans’s Union army, their supply lines increasingly vulnerable, search for Braxton Bragg’s Confederates in wooded and mountainous north Georgia (facing the growing danger that Bragg will attack each Federal column in turn), Union brigadier general John Beatty writes in his diary: “The roads up and down the mountains are extremely bad; our progress has therefore been slow and the march hither a tedious one. The brigade lies in the open field before me in battle line. The boys have had no time to rest during the day and have done much night work, but they hold up well.” Six days later, as the Union columns converge and Beatty moves his men up to a position on Chickamauga Creek, he will note: “Occasional shots along the line indicated that the enemy was in our immediate front.”65

SEPTEMBER 19–20, 1863: The bloodiest battle of the war in the western theater takes place in hostile, wooded terrain near Chickamauga Creek in north Georgia, as sixty-six thousand Confederates under Braxton Bragg clash with the sixty thousand Federals of William Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland. Union troops hold their own through the first day of bitter combat. But midway through day two, Confederates exploit a gap in the Union line, sundering the Federal army. Striking at its flanks and rear, the Rebels push most of Rosecrans’s men, and Rosecrans himself, into a full-scale retreat toward Chattanooga. (In the midst of this confusion and carnage, Union drummer boy Johnny Clem, advancing against orders to stay in the rear, picks up the gun of a slain comrade and takes part in the battle, his age and his conduct under fire making him a Union hero.) Throughout the battle, Major General George Henry Thomas, a Virginian who remains a staunch Unionist, has held the Union left; as the Union line breaks, he and his men, assisted by reserve units under Gordon Granger, continue to hold, saving this Federal defeat from becoming a complete disaster. Henceforth known as the “rock of Chickamauga,” Thomas does not withdraw his troops from the field until nightfall—and their subsequent march, Brigadier General John Beatty will note in his diary, is “a melancholy one. All along the road, for miles, wounded men were lying. They had crawled or hobbled slowly away from the fury of the battle, become exhausted, and lain down by the roadside to die…. What must have been their agony, mental and physical, as they lay in the dreary woods, sensible that there was no one to comfort or to care for them and that in a few hours more their career on earth would be ended!” Casualties from Chickamauga will exceed thirty-four thousand Union and Confederate soldiers killed, wounded, or missing. Braxton Bragg, shaken at the cost of his tactical victory, will not press after the Federals. After the Army of the Cumberland reaches Chattanooga, Bragg’s battered force will occupy the surrounding heights, including Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge, and besiege the city.66

Major General George H. Thomas (1816–1870), USA, between 1862 and 1865. Thomas’s decision to remain loyal to the Union alienated him from his family in Virginia; and his Virginia roots led some in the North to distrust him—despite his excellent record as a Civil War general.

SEPTEMBER 23, 1863: President Lincoln is summoned to a nighttime meeting at the War Department by Secretary of War Stanton, who has received a long message from Major General Rosecrans giving details of and reasons for his Chickamauga defeat. (“I know the reasons well enough,” Stanton grumbles. “Rosecrans ran away from his fighting men and did not stop for 13 miles.”) With Rosecrans’s army now trapped in Chattanooga, Lincoln, Stanton, General in Chief Halleck, and other advisers decide that they must send reinforcements. Their decision sets in motion the longest and largest movement of troops to occur before the twentieth century. Performing bureaucratic miracles, Stanton organizes the immediate transport, by rail, of more than twenty thousand men from the Army of the Potomac—their equipment, horses, and artillery. Led by Major General Joseph Hooker (no longer commanding the entire Army of the Potomac but still very much on active duty), the reinforcements will complete the 1,233-mile journey to the vicinity of Chattanooga within eleven days.67

SEPTEMBER 24, 1863: Abraham Lincoln writes to his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, currently staying at the Fifth Avenue Hotel in New York City: “We now have a tolerably accurate summing up of the late battle between Rosecrans and Bragg. The result is that we are worsted, if at all, only in the fact that we, after the main fighting was over, yielded the ground, thus leaving considerable of our artillery and wounded to fall into the enemies’ hands…. Of the [Confederate generals] killed, one Major Genl. and five Brigadiers, including your brother-in-law, [Ben Hardin] Helm.” This news adds to the growing burden of anguish pressing upon Kentucky-born Mary and her family: she and Abraham have lost two of their own sons to illness, and three of Mary’s brothers have perished fighting for the South (Sam Todd at Shiloh, David at Vicksburg, and young Alexander at Baton Rouge). Now her sister Emilie’s husband has been killed—heartrending news to both Mary and Abraham. “I never saw Mr. Lincoln more moved than when he heard that his young brother-in-law, Ben Hardin Helm, scarcely thirty-two years of age, had been killed,” Lincoln’s friend Judge David Davis will recall after the war. “I saw how grief-stricken he was… so I closed the door and left him alone.”68

Brigadier General Benjamin H. Helm (1831–1863), CSA, between 1860 and 1863. Married to Mary Todd Lincoln’s half-sister, Emily, Helm refused a commission in the Union army offered to him in 1861 by President Lincoln, choosing instead to serve the Confederate States.

Sectional View of Libby Prison, Showing Diagram of the Tunnel. Illustration from Col. Rose’s Story of the Famous Tunnel Escape from Libby Prison, by Thomas E. Rose, ca. 1890. Richmond’s Libby Prison, intensely overcrowded after the arrival of prisoners from Chickamauga, was the site of a daring February 9, 1864, escape by 109 of the prisoners. Eventually 48 of the men were recaptured, including the ringleader, Colonel Thomas E. Rose, of the Seventy-seventh Pennsylvania Volunteers. (Rose rejoined William T. Sherman’s Union army after a July 1864 prisoner exchange.)

OCTOBER

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

A Quaker Letter to Lincoln. Music by E. M. Bruce with words by Elmer Ruán Coates; music cover art by James Fuller Queen, May 1863. Many Quaker men in the Union, opposed to war on religious grounds, appealed to the president for assistance. “For those appealing to me on conscientious grounds,” Lincoln wrote to Quaker Eliza P. Gurney in September 1864, “I have done, and shall do, the best I could and can, in my own conscience, under my oath to the law.”

OCTOBER 1, 1863: In the midst of shortages and other wartime problems, including a growing population of Southern refugees, the Richmond Examiner publishes a satire based on Jonathan Swift’s “Modest Proposal” penned by correspondent George W. Bagby. Among its harshly tongue-in-cheek proposals: that poor people and refugees who have flocked to the South’s major cities be crammed into “elegant and commodious” homes made out of empty tobacco and whiskey barrels, and that food shortages be solved by resorting to cannibalism. (“The common repugnance to human food is but a foolish prejudice born of modern philosophy and political economy.”) Slaves would be among the few not condemned to be eaten, both because of racial prejudice and because it would be foolish to destroy such valuable property.69 There are some Union prisoners in Richmond who are in no mood for Confederate satire. Colonel Caleb Carolton, of the Eighty-ninth Ohio Volunteers, writes his wife, Sadie, from the city’s Libby Prison: “My regiment (that is what had not been killed, wounded, or missing) was captured just after dark on Sunday night, 20th Sept. I escaped as usual without a wound, my horse was killed under me early in the engagement…. I received a couple of pretty sharp raps from spent bullets which in addition to loss of sleep, poor food and general disgust, renders me sore cross and very much dissatisfied with my situation.” He asks her to send clothes—and books and a chess game, for “we are going to find it troublesome to pass the time here, five hundred or more officers in the three rooms with nothing to do.”70

Brigadier General John Beatty (1828–1914), USA. After service in the Union army, the eloquent Ohioan served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1868 to 1873. His wartime journals, first published as The Citizen Soldier in 1879 and later reissued as Memoirs of a Volunteer, were dedicated to “Kinsmen of the coming centuries.”

Unidentified Union sailor. Hand-colored quarter-plate tintype, between 1861 and 1865.

OCTOBER 3, 1863: With the Union army under siege in Chattanooga, Brigadier General John Beatty takes advantage of a quiet moment to write in his diary:

The two armies are lying face to face. The Federal and Confederate sentinels walk their beats in sight of each other. The quarters of the rebel generals may be seen from our camps with the naked eye. The tents of their troops dot the hillsides…. Their long lines of campfires almost encompass us. But the campfires of the Army of the Cumberland are burning also. Bruised and torn by a two days’ unequal contest, its flags are still up and its men still unwhipped. It has taken its position here, and here, by God’s help, it will remain.

Two days later, he will record something he sees during an hours-long bombardment from Confederate artillery ensconced on Lookout Mountain: “A shell entered the door of a dog tent, near which two soldiers of the Eighteenth Ohio were standing, and buried itself in the ground, when one of the soldiers turned very coolly to the other and said: ‘There, you damn fool, you see what you get by leaving your door open!’ ”71

OCTOBER 5, 1863: The formidable Union fleet blockading Charleston Harbor becomes painfully aware of a new element in naval warfare when the steam-driven, cigar-shaped Confederate torpedo boat David, riding so low in the water it can hardly be discerned, rams a torpedo into the side of USS New Ironsides. The Union’s saltwater armored warship, though damaged, is able to remain on station. David, meanwhile, almost succumbs to its own attack: water showering in after the explosion douses its power plant. But the boat’s engineer saves the day, and David escapes.72

OCTOBER 6, 1863: With the U.S. draft now in force, but without any provision for conscientious objection (see March 31 and September 27, 1862, and February 24, 1864), some draftees face heavy consequences for their nonviolent beliefs. Today, Vermont Quaker Cyrus Pringle describes his rough treatment in a diary entry:

Two sergeants soon called for me, and taking me a little aside, bid me lie down on my back and stretching my limbs apart tied cords to my wrists and ankles and these to four stakes driven in the ground somewhat in the form of an X. I was very quiet in my mind as I lay there on the ground [soaked] with the rain of the previous day, exposed to the heat of the sun, and suffering keenly from the cords binding my wrists and straining my muscles…. I wept, not so much from my own suffering as from sorrow that such things should be in our own country, where Justice and Freedom and Liberty of Conscience have been the annual boast of Fourth-of-July orators so many years.73

Chattanooga Tenn. Color map by G. H. Blakeslee, U.S. Topographical Engineers, 1863.

OCTOBER 8, 1863: “General Longstreet has written to the Secretary of War a letter which has filled me with concern,” Confederate War Department official Robert Kean writes in his diary. “He says [General Braxton] Bragg has done but one thing he ought to have done since he (General Longstreet) has been out there and that was the order to attack on September 18 [precipitating the battle of Chickamauga]… [and] he expressed the opinion that nothing will be effected under Bragg’s command.” General Bragg has long had contentious relations with his fellow officers, but his actions in the wake of Chickamauga have created particular ire—and President Davis’s efforts to encourage harmony among his snarling western generals (extending even to a visit to Bragg’s headquarters for a face-to-face meeting) will have little positive effect. On October 29, Davis will approve irate cavalryman Nathan Bedford Forrest’s request to be detached from Bragg’s army for an independent command in Mississippi and west Tennessee. Longstreet will remain restive.74

OCTOBER 13, 1863: Having run his campaign by mail while in exile in Canada, Copperhead Clement Vallandigham (see May 1 and May 7, 1863) is soundly defeated in the contest for governor of Ohio by War Democrat John Brough. Pro-Union candidates prevail in other state elections this day as well. The election results stem in part from the Union triumphs at Gettysburg and Vicksburg. Moreover, in the wake of sympathy stirred by the anti-black riots in New York City and elsewhere and public recognition of the valor of black regiments, including the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts (see July 18, 1863), emancipation, roundly attacked by Democrats, has also become less controversial to many Northern whites. In the South, suffering from shortages, inflation, and the losses at Gettysburg and Vicksburg, 1863 congressional elections will change the nature of Confederate politics by bringing more conservative and negotiation-prone legislators (known as reconstructionists or tories) to Richmond and to the governorships of several Southern states. A further faction that supports the war but does not support Jefferson Davis will also gather strength.75

OCTOBER 15, 1863: Inventor H. L. Hunley is among eight men who die when the Confederate submarine H. L. Hunley sinks (for the second time; see August 29, 1863) during a practice dive in Charleston Harbor.76

OCTOBER 17, 1863: In Indianapolis, on his way to Louisville, Kentucky, to receive new orders, General Ulysses S. Grant encounters Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, who is en route to see him. As a result of their encounter, the following day Grant will assume command of the new Military Division of the Mississippi, encompassing the Departments of the Ohio (Ambrose Burnside, commanding), the Tennessee (William T. Sherman to be named commander), and the Cumberland. Stanton allows Grant to choose whether or not to retain William Rosecrans as Department of the Cumberland commander; Grant opts to replace him with Major General George H. Thomas, whom he orders to hold Chattanooga at all costs. As Grant sets out on a difficult journey to Chattanooga, he receives Thomas’s answer: “We will hold the town until we starve.”77

Great Central Fair for the Sanitary Commission. Original watercolor-and-graphite drawing for letterhead, and color lithograph proof for the printed letterhead. Design by James Fuller Queen, 1864. Ambitious in scope, often grand in presentation, sanitary fairs became a prime method of raising funds to assist Union soldiers.

OCTOBER 24, 1863: Having arrived at Chattanooga the previous night, General Grant, accompanied by General Thomas and a party of staff officers, inspects the area. At Brown’s Ferry on the Tennessee River west of the city, they come so close to the enemy lines that they are in full view of Confederate pickets. “They did not fire upon us nor seem to be disturbed by our presence,” Grant will write in his memoirs. “They must have seen that we were all commissioned officers. But, I suppose, they looked upon the garrison of Chattanooga as prisoners of war… and thought it would be inhuman to kill any of them except in self-defense.” In the evening, Grant issues orders to open the way to Bridgeport, Alabama, establishing a supply line, or “a cracker line, as the soldiers appropriately termed it,” Grant will write. “They had been so long on short rations that my first thought was the establishment of a line over which food might reach them.” The general and his officers next turn their attention to breaking the Confederate siege.78

OCTOBER 27–NOVEMBER 7, 1863: Chicago hosts the first “sanitary fair,” a multistate Grand North-Western Fair organized to raise money, as a Chicago Sanitary Commission booklet notes, “to obtain comforts and necessaries for the sick and wounded of our army.” The two-week extravaganza begins with a procession some three miles long, which everyone can watch, since the mayor has proclaimed opening day a holiday. It proceeds to draw some five thousand people a day, their seventy-five-cent tickets admitting them to a wonderland of exhibition areas, food concessions, entertainment, and halls where donated items are offered for sale. The most precious item auctioned, donated by President Lincoln, is the original draft of the final Emancipation Proclamation, which sells for $3,000. The buyer, Thomas B. Bryan, will give the document to another Chicago Sanitary Commission project, the Soldiers’ Home. This refuge for thousands of soldiers traveling between hospitals, camps, and battlefields will eventually become a permanent home for Civil War veterans. (The document will be destroyed in the 1871 Chicago fire, though the Soldiers’ Home will survive.)79

The Great Russian Ball at the Academy of Music, November 5, 1863. Wood engraving published in Harper’s Weekly, November 21, 1863. Although Russian motives for sending their fleet to visit the Union cities of New York and San Francisco were mixed, the Union celebrated this apparent show of support from a friendly European power.

Edward Everett (1794–1865). Engraving by Henry W. Smith (b. 1828), ca. 1858. A former president of Harvard University, U.S. representative from Massachusetts, minister to Great Britain, and U.S. secretary of state, Everett wrote to Lincoln a day after the Gettysburg ceremony: “I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion in two hours, as you did in two minutes.”

NOVEMBER

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30

Triumphant Union soldiers atop Lookout Mountain, near Chattanooga, Tennessee. Color lithograph based on a drawing by James Fuller Queen, ca. 1863. After stunning action by Union troops at Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge broke the Confederate siege of Chattanooga, General Grant “rode the length of the lines,” as Charles Dana reported, and “the men, who were frantic with joy and enthusiasm over the victory, received him with tumultuous shouts.”

NOVEMBER 2, 1863: President Lincoln receives an invitation to make a “few appropriate remarks” at the November 19 dedication of the new Gettysburg National Cemetery. Despite the short notice, the president accepts.81

NOVEMBER 4, 1863: At President Davis’s suggestion, Braxton Bragg detaches some fifteen thousand men under General James Longstreet from his Army of Tennessee and sends them to Knoxville, where they will besiege that Union-occupied railroad hub in what will be an unsuccessful effort to retake the city and reestablish rail links with Virginia. (The siege will end by December 4.) While this move puts a comfortable distance between Bragg and his unhappy subordinate general (see October 8, 1863), it also weakens the Confederate siege of Chattanooga.82

NOVEMBER 5, 1863: At New York City’s Academy of Music, Americans put on a grand ball in honor of Russian diplomats and personnel of the Russian fleet, which arrived in U.S. East Coast ports in September, with other vessels docking in San Francisco in October. The United States has enjoyed cordial relations with Russia for more than a decade, Czar Alexander II being both friend and inspiration to the Lincoln administration (in 1861, the czar emancipated the Russian serfs). Although the fleet has been deployed to be well placed for action should European tensions over events in Russian Poland erupt into war, its visit has been viewed as a gesture of support for the Union, and the effect on Northern morale has been electric. Naval facilities have been placed at the Russians’ disposal, and the Russians have been honored at many social events. The Russians, in turn, won the enduring thanks of San Franciscans when they helped extinguish, at the cost of several Russian lives, a roaring fire in late October. “Russia… has our friendship,” Secretary of State William H. Seward will write on December 23, “because she always wishes us well, and leaves us to conduct our affairs as we think best.” The fleet will remain in American ports through April 1864.83

NOVEMBER 6, 1863: Having completed the journey to assume his new duties in Louisiana, Lieutenant Lawrence Van Alstyne, formerly a sergeant with the 128th New York, records in his diary what he has seen on a routine day spent organizing his new command, Company D, Ninetieth U.S. Colored Infantry, a unit comprising recently liberated slaves.

My company was examined and almost every one proved to be sound enough for soldiers. A dozen at a time were taken into a tent, where they stripped and were put through the usual gymnastic performance, after which they were measured for shoes and a suit, and then another dozen called in. Some of them were scarred from head to foot where they had been whipped. One man’s back was nearly all one scar, as if the skin had been chopped up and left to heal in ridges. Another had scars on the back of his neck, and from that all the way to his heels every little ways; but that was not such a sight as the one with the great solid mass of ridges, from his shoulders to his hips. That beat all the anti-slavery sermons ever yet preached.84

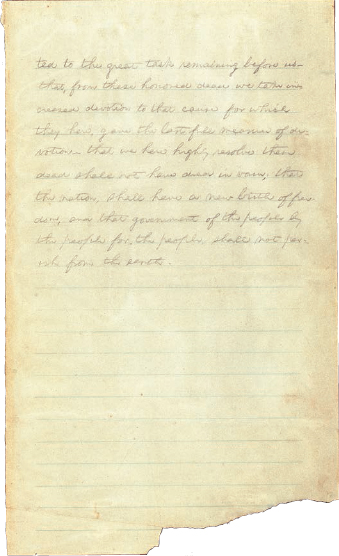

The earliest of the five known drafts of the Gettysburg Address in Abraham Lincoln’s handwriting. Known as the Nicolay copy, because it was owned by one of Lincoln’s secretaries, John Nicolay, this is presumed to be the only working, or predelivery, draft of the speech. The second page, on different paper from the first, was probably drafted in Gettysburg on November 18, during Lincoln’s overnight stay at the home of Judge David Wills.

NOVEMBER 18, 1863: President Lincoln, Secretary of State Seward, and a party from Washington, including Lincoln’s two secretaries, John Hay and John Nicolay, arrive in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, a town now “filled to overflowing,” as the New York Times will report, with people awaiting the dedication of the National Cemetery the following day. The president goes to the home of prominent local attorney David Wills, a moving force behind the establishment of the cemetery and an organizer of the dedication ceremonies. Declining an opportunity to address a crowd that comes to the house, Lincoln retires to his second-floor room, where he puts the finishing touches on the short remarks he will deliver the following day, after the day’s main address by Massachusetts statesman, scholar, and celebrated orator Edward Everett.85

NOVEMBER 19, 1863: After making final changes to his remarks, President Lincoln mounts a horse for the short ride to the cemetery. “The procession formed itself in an orphanly sort of way & moved out with very little help from anybody,” Lincoln’s secretary John Hay will write in his diary, “& after a little delay Mr. Everett took his place on the stand—and Mr. Stockton made a prayer which thought it was an oration; and Mr. Everett spoke as he always does, perfectly.” Everett’s oration, a description of the three-day Gettysburg battle that he delivered from memory, took two hours (and will meet with mixed critical reviews). President Lincoln’s remarks take about two minutes—but Lincoln has been pondering the underlying idea for years. “The central idea pervading this struggle,” he told John Hay in 1861, “is the necessity that is upon us, of proving that popular government is not an absurdity…. If we fail it will go far to prove the incapability of the people to govern themselves.” Now, adjusting his spectacles and looking out over the huge crowd, he salutes, with ringing eloquence, the thousands who have died so that the United States might have a “new birth of freedom” and calls on all those present to “highly resolve… that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”86

NOVEMBER 22, 1863: Major General William T. Sherman arrives at Chattanooga with seventeen thousand troops—and the formidable U.S. Sanitary Commission nurse “Mother” Mary Ann Bickerdyke (see May 26, 1861, and February 15, 1862), who spent most of the difficult march to Chattanooga treating soldiers’ feet and the aches, pains, and chills caused by unexpectedly cold weather. Grant’s preparations to break the Confederate siege of the city are nearly complete.87

“Glory to God!

The day is decisively ours.”

—ASSISTANT SECRETARY OF WAR CHARLES A. DANA, NOVEMBER 25, 1863

NOVEMBER 23, 1863: As Grant begins his siege-breaking operations, Union troops knock Confederates off Orchard Knob, their forward position on Missionary Ridge.88

NOVEMBER 24, 1863: Encouraged by Union commander Ulysses S. Grant to show initiative as Federal forces at Chattanooga launch their breakout attempt, General Joe Hooker leads three divisions against Confederates holding Lookout Mountain, southwest of the city. One small Confederate division under General Carter Stevenson holds the summit, supported by troops under Generals Edward C. Walthall and John C. Moore protecting the slopes. Fog that moves in as the Federals begin their assault at about 8:00 AM continues to inhibit both forces—and observers at Grant’s headquarters. Much of this “battle above the clouds” is heard but not seen. By 8:00 PM, however—Stevenson having been ordered to withdraw to reinforce Confederates battling Sherman’s troops to the northeast—the mountain belongs to the Union. By then, the field hospital below is crowded with wounded from two days’ fighting. Mother Bickerdyke is helping doctors treat the wounded, who seem to occupy every bit of available ground. With few drugs available, she flexes her belief in temperance enough to fix the men in her charge her own peculiar brew of whiskey diluted with hot water, sweetened with brown sugar, and thickened with crumpled hardtack. Tough as nails, she makes certain that, as men die, their bodies are taken outside so living soldiers can have their beds; always looking out for her soldiers, she comforts amputees who plead that their severed limbs be decently buried. It is a familiar request, though the men know perfectly well that, like animals that die in military service, amputated limbs are doused with kerosene and burned.89

NOVEMBER 25, 1863: The men of Major General George H. Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland perform the “miracle of Missionary Ridge” when they exceed their orders for a limited frontal assault and sweep Braxton Bragg’s Confederates completely off the ridge. “Glory to God! The day is decisively ours,” Assistant Secretary of War Charles A. Dana, on the scene, wires to Secretary Stanton. “No man who climbs the ascent by any of the roads that wind along its front can believe that eighteen thousand men were moved in tolerably good order up its broken and crumbling face unless it was his fortune to witness the deed,” he will later write in his memoirs. “It seemed as awful as a visible interposition of God.” With this action, the siege of Chattanooga is lifted, and the door to Georgia is open to the Union army. Confederate official Hugh Lawson Clay reflects the general mood in the Confederacy at the news when he terms the defeat a “calamity… defeat… utter ruin. Unless something is done… we are irretrievably gone.”90

NOVEMBER 27, 1863: Mississippi civilian William Delay writes to Governor Charles Clark, protesting an unhappy situation. Mississippians who crossed the Tallahatchie River to buy much-needed supplies from Southern civilians living in a Union-occupied area of the state returned to their side of the river only to have the materials they had purchased confiscated by Confederate troops. The military claimed the supplies under a Confederate sequestration law allowing the seizure of “estates, property, and effects of alien enemies,” a measure that clearly does not apply in this case—but the soldiers, low on supplies themselves, refused to return the goods even under pressure of legal writs from local civil authorities. “Can the civil law be enforced,” Delay writes in frustration, “or can the military authorities overrule and disregard all civil law?” In Ohio, Confederate cavalryman John Hunt Morgan, captured during the stunning raid he led into Northern states (see July 2, 1863), makes a daring escape from the state penitentiary at Columbus. He will make his way back to Southern lines. In Virginia, Confederates and Federals skirmish at several locations as George Gordon Meade leads the Army of the Potomac in an attempt to surprise Robert E. Lee’s army and turn its right flank. But Meade’s slow progress (due to harsh weather and the tentativeness of Meade’s lead corps, commanded by William H. French) has allowed Lee to establish strong field fortifications along the west bank of Mine Run, just south of the Wilderness. Discovering this, Meade will withdraw, much to Lee’s disgust. “I am too old to command this army,” he will say, when he realizes the Federals have gone. “I should never have permitted those people to get away.”91

Plate 30, “Amputation of the Leg,” from Illustrated Manual of Operative Surgery and Surgical Anatomy, by Claude Bernard, 1852. Dr. Stephen Smith adapted and compressed Bernard’s work into the pocket-size Hand-Book of Surgical Operations in 1862, specifically for Union army doctors. There was no manual, however, that could help the thousands of amputees on both sides of the conflict deal with the loss of their limbs.

Brigadier General John Hunt Morgan (1825–1864), CSA. Ink brush over graphite drawing, artist and date unknown. The daring cavalryman and raider was commended by the Confederate Congress for his “varied, heroic and invaluable services.”

NOVEMBER 30, 1863: General Braxton Bragg sends the first of several messages to Jefferson Davis, calling his defeat at Chattanooga “justly disparaging to me as a commander” and submitting his resignation (while also noting that the “warfare” that his subordinate officers have been carrying on against him “has been carried on successfully and the fruits are bitter”). Bitterly disappointed at the debacle in the west, Davis will accept Bragg’s resignation. But he is left with a dilemma: whom shall he send in Bragg’s place to restore order and morale in his premier western army? The officer that Bragg has left in temporary command, Lieutenant General William J. Hardee, a veteran professional soldier, does not want the job permanently. In fact, he will ask Davis to send to his army “our greatest and best leader… yourself, if practicable.”92

DECEMBER

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

Officers and Soldiers on the Battlefield of Second Bull Run, Attempting to Recognize the Remains of Their Comrades. Pencil drawing by Edwin Forbes, 1863.

“I saw battle-corpses, myriads of them, /… I saw the debris and debris of all the slain soldiers of the war, / But I saw they were not as was thought, / They themselves were fully at rest—they suffer’d not, / The living remain’d and suffer’d—the mother suffer’d / And the wife and the child, and the musing comrade suffer’d, / And the armies that remain’d suffer’d.”

—Walt Whitman, “When Lilacs Last in the Door-yard Bloom’d,” 1866

DECEMBER 7, 1863: As the Thirty-eighth U.S. Congress convenes in Washington, the Atlantic Monthly publishes a narrative that is destined to become a classic American story. Written by Unitarian minister Edward Everett Hale, a staunch Unionist and member of the Boston Union Club, “The Man Without a Country” is intended by Hale to be taken as the true account of the life of Philip Nolan, a court-martialed army officer who, in a moment of disgust and frustration, shouted, “Damn the United States! I wish I may never hear of the United States again!”—and was thereupon condemned to sail for the rest of his life on a series of U.S. Navy vessels whose crews were forbidden to speak of the United States in his presence. In line with the mission of the North’s Union Leagues, Hale intends this story as an object lesson for those Northerners who may be insufficiently aware of the importance of loyalty to the Union. “Deny the duty of loving your country,” the Reverend Joseph Fransioli will declare, in a widely circulated sermon this July, “and you deny your own feelings; you deny mankind itself.”93

Cover of The Man Without a Country by Edward Everett Hale. Illustrated by L. J. Bridgman and published by Dana Estes & Company, 1897, this is only one of many printed editions of Hale’s now famous 1863 story, which also became a 1937 movie and was filmed for television in 1973.

Negroes Leaving the Plough. Pencil and Chinese white drawing by Alfred R. Waud, March 1864. Lincoln’s Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction stipulated that seceded states would have to create a constitution that abolished slavery before they would be allowed to rejoin the Union. Since early in the war, meanwhile, slaves had been freeing themselves and seeking refuge behind Union lines, tens of thousands of the men subsequently serving in the Union armed forces.

DECEMBER 8, 1863: Aware of unrest among some Confederates over Jefferson Davis’s policies and of the growing agitation for a negotiated peace, President Lincoln issues the Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction. Offering pardon and amnesty to any secessionist (with some notable exceptions) who takes an oath of allegiance to the United States and all of its laws and proclamations relating to slavery, Lincoln’s document also outlines conditions under which seceded states might rejoin the Union; it becomes known as the Ten-Percent Plan, from the stipulation that a state might form a loyal state government (and create a constitution that abolishes slavery) when one-tenth of its voting population, as tabulated in the 1860 census, has taken a loyalty oath to the United States. “But why any proclamation now upon this subject?” Lincoln will ask rhetorically, in his annual message to Congress, also delivered this day. “By the proclamation a plan is presented which may be accepted by [the several states] as a rallying point, and which they are assured in advance will not be rejected here. This may bring them to act sooner than they otherwise would.” The proclamation is the first indication of Lincoln’s moderate approach to Reconstruction, which will place him at odds with the more punitively minded Radical Republicans. The president also writes a short letter to Ulysses S. Grant: “Understanding that your lodgment at Chattanooga and Knoxville is now secure, I wish to tender you, and all under your command, my… profoundest gratitude—for the skill, courage, and perseverance, with which you and they, over so great difficulties, have effected that important object. God bless you all.”94

DECEMBER 9, 1863: “I am called to Richmond this morning by the President,” Robert E. Lee writes to Jeb Stuart. “My heart and thought will always be with this army.” Lee is aware that Davis is on the brink of appointing him to replace Braxton Bragg as commander of the Army of Tennessee, a move Lee, for a variety of reasons, is exceedingly reluctant to make. After several days of discussion in Richmond, however, Davis will decide that Lee must remain in Virginia.95

“You should not have that rebel in your house.”

—GENERAL DANIEL E. SICKLES TO PRESIDENT LINCOLN, DECEMBER 14, 1863

Abraham Lincoln. Loyalty Oath for Emilie (Emily) Todd Helm, December 14, 1863. Lincoln wrote out the loyalty oath for Mrs. Helm at the White House, and she took the document with her when she left. She never signed it, however, and her refusal created a permanent rift with the Lincolns.

DECEMBER 14, 1863: President Lincoln writes out an amnesty declaration for his sister-in-law, Emilie Helm, whose husband was killed fighting for the Confederacy at Chickamauga (see September 24, 1863); the amnesty will become effective if and when she signs the oath of loyalty to the Union (she never does). Mrs. Helm is staying at the White House, a visit that Emilie and the Lincolns have hoped to keep as private as possible. But as the days go by, the pleasure of having her sister with her moves Mary Lincoln to invite Emilie to join the Lincolns as they entertain two friends, General Daniel E. Sickles and Senator Ira Harris. War enters the room as the men encounter Emilie’s still strong Southern pride, Sickles snapping to the president, “You should not have that rebel in your house.” The unhappy evening prompts Emilie to end her visit and Mary to sigh, “Oh Emilie, will we ever awake from this hideous nightmare?”96

DECEMBER 16, 1863: President Davis orders General Joseph E. Johnston to assume command of the Army of Tennessee. Though Davis believes Johnston to be the best choice, under the circumstances—and it is a popular one, favored by Lee and Secretary of War Seddon, among others—the president does not fully trust Johnston and does not relish making the appointment.97

DECEMBER 26, 1863: The Free Military School for Applicants for the Command of Colored Troops opens its doors at 1210 Chestnut Street, Philadelphia. The brainchild of Thomas Webster, who has helped raise several black units in Pennsylvania, the school has been established to help officer candidates—all white men at this time, many of them veterans of white regiments—pass the rigorous examination required for service as officers in black regiments. Nearly 50 percent of those who have taken the exam to date have failed. Later dubbed the “grandfather of the Officer Candidate School” by historian Dudley Cornish, the Free Military School, supervised by chief preceptor Colonel John H. Taggart, will provide a rigorous thirty-day course (though many students will stay longer) that includes both military subjects and such other courses as arithmetic, algebra, geography, and ancient history. Before it ceases operation on September 15, 1864, a total of 484 of its graduates will pass their examinations. The stringent requirements for officer candidates in the United States Colored Troops will make most of these men (some political appointees notably excepted) among the best-prepared military officers in the United States.98

DECEMBER 27, 1863: A grieving Robert E. Lee writes his wife upon learning of the death, the previous day, of their daughter-in-law, Charlotte: “It has pleased God to take from us one exceedingly dear to us & we must be resigned to His holy will…. I loved her with a father’s love, & my sorrow is heightened by the thought of the anguish her death will cause our dear son [Brigadier General William H. F. “Rooney” Lee, now a prisoner of war], & the poignancy it will give to the bars of his prison.” In northern Georgia, Brigadier General John Beatty writes pensively in his diary:

Today we picked up, on the battle-field… the skull of a man who had been shot in the head…. A little over three months ago this skull was full of life, hope, and ambition. He who carried it into battle had, doubtless, mother, sisters, friends, whose happiness was, to some extent, dependent upon him. They mourn for him now, unless, possibly, they hope still to hear that he is safe and well. Vain hope. Sun, rain, and crows have united in the work of stripping the flesh from his bones, and while the greater part of these lay whitening where they fell, the skull has been rolling about the field the sport and plaything of the winds. This is war, and amid such scenes we are supposed to think of the amount of our salary, and of what the newspapers may say of us.99

The Soldier’s Memorial. Hand-colored lithograph published by Currier & Ives, 1863.

DECEMBER 28, 1863: The Confederate Congress abolishes the practice of hiring substitutes for military service. Faced with military manpower shortages, the legislators are considering additional methods to fill the Confederate ranks.100

1864

JANUARY

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

JANUARY 2, 1864: As his Army of Tennessee commander, Joseph Johnston, calls for greater impressment of slaves to support the Confederate war effort, Irish-born Major General Patrick R. Cleburne (admiringly called “the Stonewall of the West”) proposes freeing slaves and recruiting them for service in the Confederate army. The idea touches off a bitter debate among Southern military and political leaders but yields no result (save to hinder Cleburne’s military advancement).101

JANUARY 4, 1864: In southwest Georgia, some planters have begun to hoard food, in some cases because they hope that the approaching Yankees will pay more for it than their neighbors can. “They have plenty of corn, but solemnly declare they have none to spare and refuse to sell a bushel,” Georgian Carey Stiles writes to Governor Joseph Brown. “Hundreds of thousands are now without a particle of bread, and under this state of things they must starve or, driven to desperation by hungry starvation, resort to the violence of bread riots and mobocracy…. If something is not done, and quickly to force these corn cormorants to open their cribs to the poor & the non producers it will burst in all its fury.”102

Major General Patrick R. Cleburne (1828–1864), CSA. Born in Ireland, Cleburne proved to be a supremely effective battlefield commander who held the respect of his men by demonstrating his concern for their welfare and his own unrelenting courage under fire.

Southern Women Feeling the Effects of the Rebellion, and Creating Bread Riots. Wood engraving published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, May 23, 1863. By 1864, Richmond and other cities had already experienced bread riots, and in his letter to the governor of Georgia (see text for January 4, 1864), Carey Stiles cautioned that conditions in the state might spark others.

JANUARY 5, 1864: Black citizens of New Orleans draw up a petition addressed to President Lincoln and the U.S. Congress asking for the right to vote. The petition bears the signatures of more than a thousand men, twenty-seven of whom fought under Andrew Jackson at the battle of New Orleans in 1815. Two of the signers, Jean Baptiste Roudanez and Arnold Bertonneau, are selected to carry the petition to Washington (see March 12, 1864).103

JANUARY 7, 1864: President Davis names William Preston, former U.S. ambassador to Spain, Confederate envoy to Mexico, where the French, long sympathetic to the Confederacy, are fighting to displace President Benito Juárez with a puppet emperor, Maximilian, a prince of the Austro-Hungarian empire. The Union opposes the French action. The Confederacy supports it, chiefly because it increases the likelihood of French recognition (Maximilian has told more than one Southern visitor to Europe that he supports Confederate independence). Preston, in Cuba, will await notification that he is to assume his new post.104

JANUARY 9–12, 1864: Sergeant William Walker, of the Twenty-first U.S. Colored Infantry, is tried before a court-martial for inciting a mutiny after he refused to perform military duties because the U.S. government is discriminating against black soldiers regarding pay. He is convicted—and is executed before President Lincoln has a chance to review the case. “The Government which found no law to pay him except as a nondescript and a contraband,” Massachusetts governor John A. Andrew will later say, “nevertheless found law enough to shoot him as a soldier.”105