MAY

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

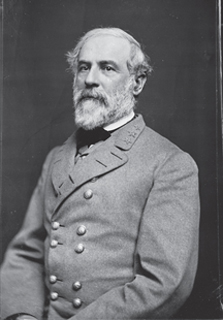

General Robert E. Lee (1807–1870), CSA. Photograph by Julian Vannerson, March 1864. With his Army of Northern Virginia, Lee formed the heart of the Confederate military effort. His reputation caused some Union officers to regard him as having almost superhuman qualities (see May 8, 1864). “But I had known him personally and knew that he was mortal,” Ulysses S. Grant wrote in his memoirs, “and it was just as well that I felt this.”

MAY 2, 1864: The Second Confederate Congress convenes in Richmond. In the wake of the fall 1863 elections, its makeup has changed from overwhelmingly secessionist to a legislature that includes a near balance of ardent secessionists and more conservative former Whigs and Unionists. Some members represent areas under Union control—a phenomenon that will expand as the war continues. The more conservative members of Congress, as well as a number of state officials, will continue to object to some of President Davis’s war policies as conflicting with states’ rights as the war moves into its fourth year. Meanwhile, both the Confederate military and Southern civilians will face increasing shortages and the relentless encroachments of Federal armies.7

MAY 4, 1864: Just after midnight the Army of the Potomac begins to move forward, embarking on Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant’s Overland Campaign. Headquartered with this army, which is still under the command of Major General George Gordon Meade, Grant has also directed Major General Franz Sigel and his troops to move southward up Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley while Major General Benjamin Butler begins a campaign south of Richmond; at the same time, Major General William T. Sherman is to begin operations against General Joseph Johnston’s Army of Tennessee in Georgia. Abraham Lincoln’s new general in chief is thus finally realizing the coordinated multifront operation against Confederate forces that the president has long advocated. Grant’s plan for confronting Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia is to move around the Confederate right flank, quickly traversing the treacherous Wilderness area in which the battle of Chancellorsville took place a year earlier (see May 2–4, 1863), and, having placed the Army of the Potomac between Lee’s army and Richmond, fight Lee in open territory. Yet Meade’s huge army, with all its accoutrements, moves slowly. When Meade calls a halt to marching for the day (believing, erroneously, that Lee’s army is still miles away behind its fortifications), the Army of the Potomac is still in the Wilderness.8

MAY 5, 1864: Having embarked from Fort Monroe the day before and left garrisons at key locations along the way, Major General Benjamin F. Butler and thirty thousand of his thirty-nine-thousand-man Army of the James arrive at Bermuda Hundred Landing. A large neck of land just fifteen miles south of Richmond, Bermuda Hundred is strategically important because of the Richmond & Petersburg Railroad, a vital connection between the Confederate capital and points south—particularly the important railroad center of Petersburg, only seven miles distant. Butler and his troops begin pushing westward, but their progress is ponderously slow (see May 7, 9, 13, and 16, 1864). Some miles to the northwest, Grant’s plan to reach open ground before meeting Lee comes to naught when elements of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia engage the Army of the Potomac, beginning the harrowing two-day battle of the Wilderness. “If any opportunity presents itself of pitching into a part of Lee’s army,” Grant orders Meade after he learns of the Confederates’ surprise appearance, “do so without giving time for disposition.” Union officers move more slowly in getting their men into battle than their Confederate counterparts, but before long, as one Federal will write, “these hitherto quiet woods seemed to be lifted up, shook, rent, and torn asunder.” Storms of musket fire and bursting artillery shells set patches of underbrush in the dry woods ablaze as the battle becomes, in one Confederate’s description, “a butchery pure and simple.” Both sides suffer heavy casualties, and some of the wounded, lying helpless in the paths of the crackling fires where no one can reach them, perish in the flames, their anguished cries continuing to haunt the Wilderness after fighting stops for the night. As exhausted soldiers of both sides huddle in the flickering darkness, Grant plans to take the initiative the following day.9

Wounded Escaping from the Burning Woods of the Wilderness. Pencil and Chinese white drawing by Alfred R. Waud, May 5–7, 1864. Despite rescue efforts by many of their comrades, some wounded soldiers perished in the flames. “This is one of the horrors of fighting in dense woods,” Union soldier Josiah Marshall Favill wrote after the Wilderness battle, “where the bursting shells invariably in dry weather set fire to the dead leaves and branches.”

MAY 6, 1864: At 5:00 am, the Wilderness erupts into action as some thirty thousand Federals smash into Lieutenant General A. P. Hill’s weakened Third Corps on the right flank of the Army of Northern Virginia. Having suffered heavily in the previous day’s fighting, and unprepared for the attack, the Confederates fall back—until elements of Lieutenant General James Longstreet’s First Corps, General Robert E. Lee in their midst (but prevented by his worried soldiers from actually leading the attack), arrive in the nick of time. Slamming into the Union troops, the Confederates precipitate a two-hour spate of intense fighting, forcing Union troops under Major General Winfield Scott Hancock and Brigadier General James S. Wadsworth to fall back and regroup. Wadsworth is mortally wounded while rallying his men—and the Confederates also suffer bitter losses among their top officers. Only four miles from where Stonewall Jackson was mortally wounded during the battle of Chancellorsville (see May 2–4, 1863), General Longstreet is seriously wounded by Confederates who mistake the First Corps commander and the men riding with him for Union officers. (Two of Longstreet’s staff officers and Confederate brigadier general Micah Jenkins are killed by the same “friendly fire.”) Major General Richard H. Anderson assumes Longstreet’s command, but the Confederate counterattack against the left of the Union line is stalled. A renewal of the assault later in the day proves ineffective, as does an attack on the Union right by three Southern brigades under Brigadier General John Brown Gordon. Although the Confederates end the day preparing for a third day of fighting, this first clash of the Overland Campaign ends with the coming of dark. Generally regarded as a tactical draw, the battle of the Wilderness has cost the Union 17,600 killed, wounded, and captured; the Confederates have suffered nearly 11,000 casualties.10

MAY 7, 1864: Pushing slowly toward the Richmond & Petersburg Railroad from Bermuda Hundred Landing, an eight-thousand-man contingent of Major General Benjamin Butler’s Union Army of the James meets twenty-six hundred Confederate troops under Brigadier General Bushrod Johnson and pushes them back. Meanwhile, Butler’s cavalry, under Brigadier General August Kautz, is engaged in the first of several raids to destroy Confederate supplies and disrupt the enemy’s communications. (The raids will prove to be largely ineffective, as the Confederates will quickly repair most of the damage done.) In Georgia, Major General William T. Sherman’s one-hundred-thousand-man force—comprising the Army of the Tennessee under Major General James B. McPherson, the Army of the Cumberland under Major General George H. Thomas, and the Army of the Ohio under Major General John M. Schofield—begins in earnest its campaign against General Joseph E. Johnston’s sixty-thousand-man Army of Tennessee, which is so well entrenched on high ground at Dalton, Georgia, that Sherman decides against a frontal assault. He will, instead, attempt to turn Johnston’s left flank. In the Wilderness, after a day marked by probing clashes between Union and Confederate skirmishers and, to the south of the main armies, a nearly daylong clash between Union and Confederate cavalry, Grant withdraws his forces under cover of darkness and starts them marching—in a direction that both surprises and elates his army and people throughout the North. “The previous history of the Army of the Potomac had been to advance and fight a battle, then either to retreat or to lie still, and finally to go into winter quarters,” Charles A. Dana will write after the war. “As the army began to realize that we were really moving south… the spirits of men and officers rose to the highest pitch of animation. On every hand I heard the cry, ‘On to Richmond!’ ” Unbeknownst to his troops, Grant has promised Lincoln that “whatever happens, there will be no turning back.” Yet his enemy is equally determined. “[T]here were to be a great many more obstacles to our reaching Richmond than General Grant himself, I presume, realized on May 8, 1864,” Dana will write. “We met one that very morning; for when our advance reached Spottsylvania [sic] Courthouse it found Lee’s troops there, ready to dispute the right of way with us.”11

A Short History of J. [James] Longstreet. Booklet in a series designed to be included in cigarette packs, 1888. Commander of the First Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia during the battle of the Wilderness, Lieutenant General Longstreet was seriously wounded by Confederates who mistook him for an enemy.

Brigadier General James S. Wadsworth (1807–1864), USA. Photograph by the Brady National Photographic Art Gallery, between 1860 and 1864. A wealthy philanthropist who kept a firm eye on the welfare of his troops, Wadsworth was described by Illinois senator Orville H. Browning as “firm in his hostility to slavery and rebellion.” He was killed at the battle of the Wilderness.

Charles A. Dana (1819–1897), assistant secretary of war, USA, at Cold Harbor, Virginia, July 11 or 12, 1864. Photographer unknown. The former managing editor of Horace Greeley’s New York Tribune, Dana was an ardent and eloquent Unionist. As assistant secretary of war, he often went into the field to observe operations firsthand.

MAY 8, 1864: Finding Lee’s First Corps under Richard Anderson digging in at Spotsylvania when he and his men arrive at about 8:00 am, the Army of the Potomac Fifth Corps commander, Major General Gouverneur Warren, launches a series of unsuccessful piecemeal attacks against Anderson’s position before being joined first by Major General John Sedgwick’s Sixth Corps and slowly by other elements of the Union force. In the evening, after Confederates repulse a final assault on their works, General Meade orders that “the army will remain quiet to-morrow.” They will be quiet but active, entrenching and building field fortifications. Grant, meanwhile, has become concerned over what he deems the insufficient aggressiveness of the Army of the Potomac’s leading officers, an attitude that had been ingrained by two and a half years of cautious leadership and battlefield setbacks. “Oh, I am heartily tired of hearing about what Lee is going to do,” he had said, two days before, to officers worrying about the Confederate commander’s intent. “Some of you always seem to think he is suddenly going to turn a double somersault, and land in our rear and on both of our flanks at the same time. Go back to your command, and try to think what we are going to do ourselves, instead of what Lee is going to do.” In the evening, Grant agrees to a course of action suggested by the Army of the Potomac’s cavalry commander, Major General Phil Sheridan: he orders Sheridan to take his ten thousand horsemen (leaving one regiment with the army) and “proceed against the enemy’s cavalry.”12

Major General John Sedgwick (1813–1864), USA. Photograph by the Brady National Photographic Art Gallery, between 1860 and 1864. A West Point graduate and veteran of the Mexican War, Sedgwick was among the most beloved officers of the Army of the Potomac, which deeply mourned his death from sniper fire.

MAY 9, 1864: As Sherman’s army continues to probe the Confederate Army of Tennessee’s defenses at Dalton, Georgia (some of the probes resembling full-scale attacks), Butler’s Federals are repulsed by Confederates at Swift’s Creek. After Butler timidly orders a withdrawal behind fortifications on Bermuda Hundred, the more disgruntled of his men dub this campaign their “stationary advance.” Some miles to the north, the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia have a relatively quiet day, though it is one punctuated by gunfire. In the morning, Union Sixth Corps commander John Sedgwick, seeing a man flinch from the Confederate shooting, says, “Why, what are you dodging for. They could not hit an elephant at that distance.” An instant later, an enemy bullet smashes into his head below the left eye, killing him instantly. “ ‘Uncle John’ was loved by his men as no other corps commander ever was in this army,” Colonel Charles S. Wainwright will note in his diary. For the Federals, this “quiet” day becomes a day of mourning.13

MAY 10, 1864: Probing for weaknesses in the Confederate fortifications at Spotsylvania, Grant launches attacks against Lee’s well-entrenched troops, initiating combat in which intense firing traps the battling soldiers in a storm of lethal metal. Refusing to give up despite the growing cost of these assaults, the Union general in chief approves a plan proposed by twenty-four-year-old Colonel Emory Upton, a West Point graduate and a sharp and ambitious student of military tactics. Upton believes that attacking in columns several soldiers deep, rather than in single lines, will provide the punch required to breach the Confederate defenses. Now, given twelve of the best regiments in the Army of the Potomac’s Sixth Corps, he vows to General David A. Russell, “I will carry those works. If I don’t, I will not come back.” Forming the regiments in three columns, each column four lines deep, Upton explains to the men that he is going to lead them in an assault on the salient (forward protrusion) in Southern lines known as the Mule Shoe. “I felt my gorge rise, and my stomach and intestines shrink together in a knot,” one New Yorker will later remember. “I looked about in the faces of the boys around me, and they told the tale of expected death.” A fury of Confederate fire lashes into the columns as they near the Rebel lines, but the Federals have been ordered to push on no matter what, and they do; the first lines take a brutal pounding in hand-to-hand fighting, but those behind them surge over the fortifications. Yet this is just a temporary victory; when support from other Union troops does not materialize as planned, Confederate reinforcements surge forward and push Upton’s troops back. It is a bitter pill for the surviving Federals to swallow. The attack has cost the Union about one thousand killed and wounded; the Confederates have lost a similar number, plus some twelve hundred prisoners. Still, this assault has shown Grant and his officers that a strong enemy position can be overcome with ample concentration of—properly supported—force. Upton will shortly receive a promotion to brigadier general.14

Major General Emory Upton (1839–1881), USA. Photograph by the Brady National Photographic Art Gallery, circa 1865. After graduating from West Point in May 1861 with the rank of lieutenant, Upton rapidly rose through the ranks, promoted to brigadier general for his service at Spotsylvania and becoming a major general by the end of the war.

Major General James Ewell Brown (Jeb) Stuart (1833–1864), CSA, between 1861 and 1864. After resigning from the U.S. Army, Stuart commanded the cavalry that were the eyes of Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. He twice led his men on raids that thoroughly embarrassed the Federal Army of the Potomac.

MAY 11, 1864: During a lull in the fighting at Spotsylvania, the people of Richmond are seized by convulsions of worry as they learn that a Union force is approaching the city. Notices go up all over the city: “The enemy… may be expected at any hour, with a view to [Richmond’s] capture, its pillage and its destruction. The strongest consideration of self and duty to the country, calls every man to arms!” Only six miles to the north, at Yellow Tavern, Virginia, Jeb Stuart and three thousand Confederate horsemen (half the Rebel cavalry remain with Lee at Spotsylvania) manage to interpose themselves between Sheridan’s cavalry and the Confederate capital. In the ensuing helter-skelter battle, a bullet fired by a soldier of George A. Custer’s Michigan Brigade strikes Stuart in the abdomen. As the two forces disengage, Stuart’s men carry him back to Richmond by a circuitous route, avoiding the advancing Federals; Sheridan’s men move on and bump up against the city’s defenses (Sheridan determining it would be too costly to take the city) before heading off to the east.15

MAY 12, 1864: Enticed from behind Union fortifications by Confederate movements along the James River, Major General Benjamin Butler leads fifteen thousand of his Army of the James infantry toward Drewry’s Bluff, which is only eight miles below Richmond, on the James River. At Spotsylvania, the apex of the Mule Shoe salient (see May 10, 1864) becomes known as the “Bloody Angle” during a rain-drenched day of brutal hand-to-hand fighting that commences at 4:30 am, when twenty thousand massed Union troops under Major General Winfield Scott Hancock surge out of the fog, over the Confederate fortifications, and into the Rebel soldiers firing from their trenches. By the end of this epically bloody day, which Private John Haley, of the Seventeenth Maine, will describe as “a seething, bubbling, roaring hell of hate and murder,” the Confederates have fallen back to a new line at the base of the salient—and survivors on both sides are shaken by the terrible fighting they have just been through: “It was the most desperate struggle of the war,” veteran campaigner Dr. Spencer Glasgow Welch, of the Thirteenth South Carolina Volunteers, will write to his wife the next day. “I do not know that it is ended… but I hope the Yankees are gone and that I shall never again witness such a terrible day as yesterday was.” The Yankees are not gone. There will be two more all-out clashes (May 18 and 19)—bringing the total number of Spotsylvania killed, wounded, and missing to some eighteen thousand Federals and twelve thousand Confederates—before Grant withdraws to try again to push forward around Lee’s right flank. In Richmond, after suffering through the day and calmly setting his affairs in order, at 7:38 PM thirty-one-year-old Jeb Stuart dies of his wound at the home of his brother-in-law, Dr. Charles Brewer. Newspapers quickly publish accounts of his last hours; but it will be eight days before a grieving Robert E. Lee is able to issue General Orders, No. 44, announcing Stuart’s death to his men: “His grateful countrymen will mourn his loss and cherish his memory. To his comrades in arms he has left the proud recollection of his deeds, and the inspiring influence of his example.”16

Brigadier General Franz Sigel (1824–1902), USA. Photographic print on a carte de visite mount, circa 1861. A German immigrant and military academy graduate, Sigel proved to be a less than distinguished Civil War battlefield commander and retired from the service after the battle of New Market. His greatest service to the United States was in rallying German Americans to the Union cause.

Corporal Alvin B. Williams, Company F, Eleventh Regiment, New Hampshire Volunteers, killed at age eighteen near Spotsylvania Court House, Virginia, May 12, 1864—three weeks after his brother, Oscar, also serving in the Eleventh New Hampshire, died in an army hospital of pneumonia. Hand-colored ambrotype, date and photographer unknown.

Corporal Alvin Williams’s dogtag.

MAY 13, 1864: Having pushed Confederates back from their forward positions and into their main lines at Drewry’s Bluff (see May 12, 1864), Major General Benjamin Butler does not press after them but holds his fifteen thousand Union troops in a defensive position. As he ponders his next move, Confederate reinforcements will arrive from Richmond and North Carolina. From Washington, Walt Whitman writes his mother: “Yesterday and to-day the badly wounded are coming in…. I steadily believe Grant is going to succeed, and that we shall have Richmond—but O what a price to pay for it.”17

MAY 15, 1864: Confederates led by Major General John C. Breckinridge, a former U.S. vice president, defeat Union troops under General Franz Sigel at the battle of New Market, in the Shenandoah Valley. In this encounter, which allows Confederates to hold on a little longer to the valley, widely known as the “Breadbasket of the Confederacy,” Breckinridge’s troops include 247 Virginia Military Institute cadets whose courageous charge makes them instant Southern heroes. Disappointed in this Federal loss, General in Chief Grant and Chief of Staff Henry Halleck will urge President Lincoln to replace Sigel, who, the two officers believe, “will do nothing but run; he never did anything else.” On May 21, Major General David Hunter will assume command in the valley.18

MAY 16, 1864: At 4:45 am, Confederates under General P. G. T. Beauregard burst from their lines and hit Major General Benjamin Butler’s Union troops, beginning the second battle of Drewry’s Bluff. Though the attack’s organization is partially confounded by heavy fog, the Confederates are able to force the Federals back, Butler leading them to the Bermuda Hundred fortifications they had left not long before. The following morning, Confederate troops will arrive and position themselves across the narrow neck of land opposite those fortifications, making it impossible for the Army of the James to move forward. The Federal commander, who has been known, at least in Southern circles, as Beast Butler, since the infamous “women’s order” he issued in New Orleans (see May 15, 1862), now becomes known as Bottled Up Butler.19

As the war progressed, armies of each side became adept at entrenching and erecting field fortifications, such as the ones Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia hastily erected at the North Anna River, discouraging Union assault (see May 23–26, 1864). This sketch, by Union soldier Anson Smith, depicts a Union fortification that his regiment, the 104th Illinois, constructed in Tennessee to guard the strategically vital Louisville and Nashville Railroad.

MAY 20, 1864: Weary in body and spirit from the near-ceaseless pounding they have been taking and the loss of so many in their ranks, yet still stubbornly determined, the men of the Army of the Potomac begin to withdraw from their lines at Spotsylvania. They continue their movement south, Grant believing (erroneously) that he might be able to catch the equally battered and determined men of the Army of Northern Virginia in the open as Lee maneuvers to keep his force between Grant’s army and Richmond. The Federals forage as they march, exhibiting little of the consideration for the property of Confederate civilians that characterized the first year of the war. Meanwhile, after crossing the North Anna River, Lee will order his army to halt and quickly erect field fortifications—something at which they have become surpassing experts during this brutal campaign.20

MAY 23–26, 1864: Leaving some of their men to guard the north bank, Grant and Meade send the bulk of the Army of the Potomac across the North Anna River—where the Union force immediately runs up against Lee’s entrenched Confederates, whose inverted-V-shaped lines pose difficult tactical problems. After some piecemeal attempts to penetrate the Rebel position, Grant and his officers decide, as Grant informs Washington, that “to make a direct attack from either wing [each Union wing facing one side of the Confederate V] would cause a slaughter of our men that even success would not justify.” Grant decides to recross the North Anna and move around Lee’s flank, making “one more effort,” as he will write in his memoirs, “to get between him and Richmond. I had no expectation now, however, of succeeding in this; but I did expect to hold him far enough west to enable me to reach the James River high up.” During the North Anna operations, Phil Sheridan and his cavalry, their two-week raid concluded (see May 8 and 11, 1864), rejoin the Army of the Potomac.21

MAY 26, 1864: Despite shortages of manufactured goods throughout the Confederacy, “blockade-running,” or sneaking through the Federal blockade of the Southern ports to sell goods for immense profit, becomes widespread enough for Jefferson Davis to complain in a speech that “50 or 60 millions have gone into blockade-running while not a new dollar has gone into manufacturing.”22

MAY 28, 1864: General Lee reports to President Davis that his best guess at the enemy’s route has led him “to take position on the ridge between the Totopotomoi [sic] and Beaver Dam Creeks, so as to intercept his march to Richmond,” yet “the want of information” now leads him to doubt if his calculations are correct. As he writes, Army of the Potomac cavalry searching for Lee collide with Confederate cavalry searching for Grant at Haw’s Shop near Hanovertown. During the fight, George A. Custer leads his dismounted Michigan Brigade in a charge that routs the Rebels—not the first time the young Union general has demonstrated effective leadership under fire. “So brave a man I never saw and as competent as brave,” one of his officers writes. “Under him our men can achieve wonders.” For the next few days, Federals and Confederates will clash intermittently as Grant continues to move his troops toward the James River.23

Grand Banner of the Radical Democracy, for 1864. Color lithograph with watercolor published by Currier & Ives, 1864. No friend of Lincoln since the president relieved him of command in August 1861, John C. Frémont, with his running mate, John Cochrane, led a brief and abortive campaign to replace the Lincoln administration in 1864.

A button from the 1860 presidential campaign features a Mathew Brady photograph of vice presidential candidate Hannibal Hamlin, senator from Maine. A similar button from the 1864 presidential campaign features a photo, taken by Anthony Berger of the Brady National Photographic Art Gallery, of Hamlin’s replacement, vice presidential candidate Andrew Johnson of Tennessee.

MAY 31, 1864: A group of some four hundred white radicals who have formed the Radical Democracy Party meet in Cleveland, Ohio, and nominate famed explorer and former Union general John C. Frémont as their candidate for president of the United States (see August 30, 1861). The party platform stipulates that there must be no compromise with the Confederacy and supports equal rights for blacks in the South and a constitutional amendment banning slavery. Although a majority of blacks unswervingly support Lincoln, several influential African American leaders, including Frederick Douglass, initially lean toward Frémont, feeling that the president is too cautious and lenient in his terms for Reconstruction. In Virginia, Army of the Potomac cavalry units occupy Old Cold Harbor. They have been ordered to hold this position until their infantry arrives. As Confederate troops from Lee’s Totopotomoy Creek position as well as from Richmond arrive in the area, the Union horsemen comply with their orders, repulsing Rebel attempts to dislodge them. Meanwhile, the Confederates form a new line just east of New Cold Harbor—and only a dozen miles from the Confederate capital.24

JUNE

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30

Kearsarge and Alabama. Color lithograph published by L. Prang & Co., 1887. A particularly painful thorn in the Union’s paw, Confederate commerce raider Raphael Semmes’s vessel CSS Alabama was finally caught and destroyed, an event that caused mourning throughout the South. Alabama’s nemesis, USS Kearsarge, was captained by John A. Winslow, who had been a friend and shipmate of Semmes during the Mexican War.

JUNE 1, 1864: The battle of Cold Harbor begins late in the day as two newly arrived Federal infantry corps, ordered forward by General Meade, attack Lee’s entrenched Confederates—and are repulsed with some two thousand casualties. As the survivors return to the lengthening Union lines, Major General Winfield Scott Hancock’s Army of the Potomac Second Corps, still some distance from Cold Harbor, begins a forced march in order to be in position for a full-scale assault that Grant has ordered for the following day. It is a difficult night for men already worn down from a month of brutal campaigning. When Hancock’s men arrive at Cold Harbor on June 2, Grant will postpone his planned attack for a day “by reason of the exhausted state of the 2nd Corps.” Confederates have been on the march, too; Lee has received reinforcements from Bermuda Hundred and the Shenandoah Valley. In Mississippi, Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest leads his cavalry out of Tupelo, heading northeast into Alabama and toward the Nashville & Chattanooga Railroad, the supply lifeline for Major General William T. Sherman’s one-hundred-thousand-man force now pursuing General Joseph Johnston’s Confederate army in Georgia. Uncomfortably aware of Forrest’s expertise at disrupting Federal supply lines, as he had done effectively during the first Union campaign for Vicksburg (see December 21, 1862), Sherman has already ordered Brigadier General Samuel D. Sturgis to distract Forrest by threatening northern Mississippi. Sturgis will lead eighty-one hundred Union troops out of Memphis on June 2.25

Cold Harbor, Virginia (vicinity). Collecting Remains of Dead on the Battlefield. Photograph by John Reekie, April 1865. The site of a three-day battle during the Union’s costly Overland Campaign, Cold Harbor included a final, hour-long frontal assault on Confederate entrenchments that caused more than three thousand Federal casualties; casualty estimates for the entire battle exceed seventeen thousand men killed, wounded, and missing.

JUNE 3, 1864: At 4:30 am, infantrymen of the Second, Sixth, and Eighteenth Corps of the Army of the Potomac advance on the Army of Northern Virginia’s formidable lines at Cold Harbor—and are met by a wall of lacerating musket and artillery fire that fells ranks of men “like rows of blocks or bricks pushed over by striking against each other,” as one survivor will remember. After one searing hour, during which thirty-five hundred Federal soldiers are killed or wounded, the assault fails. Yet gunfire does not cease. Thousands of Union soldiers, both unhurt and wounded, lie trapped in the open between Federal and Confederate lines; their slightest movement sparks Rebel fire that causes more than a thousand additional casualties before darkness brings an end to this terrible day. “I have always regretted that the last assault at Cold Harbor was ever made,” Grant will write in his memoirs. “[N]o advantage whatever was gained to compensate for the heavy loss we sustained.” As both armies work to strengthen their positions, Grant and Lee will begin an exchange of messages about the men of both armies who are suffering between the lines. Marked by delays and misunderstandings, the negotiations will take more than forty-eight hours; during that time, as Grant will later note, “all but two of the wounded had died.”26

JUNE 6, 1864: William T. Sherman’s ploy to keep Confederate cavalry commander Nathan Bedford Forrest away from his army’s vital railroad supply line proves effective when Major General Stephen D. Lee recalls Forrest from his raid. Forrest and his men are to find and intercept Samuel D. Sturgis’s Union column, which is threatening northeastern Mississippi. (See June 1 and 10, 1864.)27

JUNE 7, 1864: Both to harass the enemy and to divert attention from the next phase of his Overland Campaign, General in Chief Grant sends Phil Sheridan and nine thousand cavalrymen on a mission to destroy as much as possible of the Virginia Central Railroad, then move on to Charlottesville to connect, if feasible, with David Hunter’s Shenandoah Valley contingent (Hunter will actually remain in the valley; see June 11–12, 1864). Sheridan departs while somber music from Union bands echoes in the air: the Federals are burying the dead they have finally been able to retrieve from the killing ground between Union and Confederate lines (see June 3, 1864). In Washington, Walt Whitman writes to his mother about “one new feature” of the wounded soldiers crowding the city’s hospitals: “Many of the poor a∆icted young men are crazy. Every ward has some in it that are wandering. They have suffered too much, and it is perhaps a privilege that they are out of their senses.”28

JUNE 8, 1864: In Baltimore, delegates from twenty-five states attend the Republican Party Convention (redesignated the National Union Party Convention this year, to attract War Democrats). Although there has been some agitation to replace Abraham Lincoln as the party’s candidate (see, for example, January 13 and February 22, 1864), his nomination is a foregone conclusion. When it is achieved, a band erupts with a rousing “Star-Spangled Banner” and, as the National Republican will report, “the audience rose en masse, and such an enthusiastic demonstration was scarcely ever paralleled.” Delegates then bump Vice President Hannibal Hamlin from the ticket, replacing him with Tennessee Unionist Andrew Johnson (see July 11, 1861). In Washington, Lincoln is following convention events as best he can from the War Department telegraph office. He will not be officially notified of his renomination, however, until a delegation calls at the White House the following day.29

Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest (1821–1877), CSA. A prewar slave trader, Forrest became one of the Confederacy’s most talented and resourceful cavalry commanders. His victory at Brice’s Crossroads brought him the official thanks of the Confederate Congress.

Jones’ Landing, Va., vicinity. Pontoon Bridge over the James, from the North Bank, date and photographer unknown. Reaching the James River at the end of the Overland Campaign, engineers of the Army of the Potomac built a pontoon bridge that allowed Grant’s huge army to cross. It would remain the longest floating bridge ever erected until the record was broken during World War II.

JUNE 10, 1864: Confederates under Nathan Bedford Forrest trounce Samuel Sturgis’s Union force at the battle of Brice’s Crossroads, Mississippi. Defeating the thirty-three-hundred-man Union cavalry first, the Confederates then duel Sturgis’s infantry for four hours before the Federals break and run. They are saved from total disaster by action of one brigade, comprising three regiments of U. S. Colored Troops. Often fighting hand-to-hand, with almost no assistance from white volunteers, the black soldiers hold the Confederates back long enough to allow the balance of the Federal force to escape. In the North Atlantic, having by now taken some sixty-five Union vessels as prizes, Raphael Semmes, captain of the famed and feared Confederate commerce raider CSS Alabama, welcomes an experienced English Channel pilot aboard his vessel as it enters the channel en route to getting a much-needed refit in France. “I felt great relief to have him on board,” Semmes writes in his diary. “And thus, thanks to an all-wise Providence, we have brought the cruise of the Alabama to a successful termination.” Yet it is too soon for Semmes to relax; Alabama is being pursued.30

JUNE 11–12, 1864: More than six thousand Confederate cavalrymen led by Major General Wade Hampton intercept Phil Sheridan’s Union cavalry at Trevilian Station, Virginia, precipitating a two-day battle that will become the bloodiest cavalry clash of the war. Action on June 11 includes a desperate three-hour struggle for survival by George Custer’s surrounded Michigan Brigade, which is finally relieved when other Federal troops punch a hole in the Confederate line. On June 12, after Confederates repulse seven charges by Sheridan’s dismounted men throughout the day, Sheridan decides to withdraw toward Cold Harbor, taking with him as many as possible of his one thousand wounded, plus prisoners and runaway slaves. Hampton’s Confederates, who have suffered eleven hundred casualties, have put an end to the Union raid before it has truly started. Over these same two days, in the Shenandoah Valley, David Hunter’s Union troops storm into Lexington, Virginia, site of the Virginia Military Institute (VMI), whose cadets won plaudits for joining in the battle of New Market the previous month (see May 15, 1864). Harassed for a month by Rebel guerrillas, who have prevented most of their supply wagons from getting through to them, the Yankees are hungry and incensed at civilians they believe are supporting the irregulars. Today, they forage with a vengeance—and for good measure burn down VMI and the home of Virginia governor John Letcher, who recently issued what Hunter will describe as “a violent and inflammatory proclamation… inciting the population… to rise and wage a guerrilla warfare on my troops.” As Hunter leads his troops toward Lynchburg, Robert E. Lee orders Jubal Early to lead the Second Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia into the valley to neutralize this Union threat.31

The War in Virginia—a Regiment of the 18th Corps Carrying a Portion of Beauregard’s Line in Front of Petersburg. Wood engraving based on a sketch by E. F. Mullen, published in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, July 23, 1864. Although they vastly outnumbered the city’s Confederate garrison when they arrived at Petersburg in mid-June, Grant’s battered troops, wary after weeks of brutal campaigning, failed to take this vital rail hub. Instead, Petersburg became the object of a Union siege that lasted for months.

JUNE 12, 1864: General Grant begins one of the most remarkable troop movements of the war. Withdrawing the Army of the Potomac from its lines at Cold Harbor after dark, he leads the huge force across the Virginia Peninsula. By June 14, it will arrive at the north bank of the James River—which Lee had told Jubal Early it was essential to keep the Federals from crossing. As some Federals cross the water by boat, Grant’s engineers construct a 2,170-foot pontoon bridge—the longest floating bridge erected before World War II. When, at 11:00 pm, they finish assembling this marvel, bands play, drummers drum, and troops begin streaming across the new span, an operation that will continue for nearly two days. It is, as Colonel Horace Porter, of Grant’s staff, will later say, “a matchless pageant that could not fail to inspire all beholders with the grandeur of achievement and the majesty of military power.”32

JUNE 14, 1864: Reporting to Washington on his movements, Grant wires Chief of Staff Halleck: “The enemy show no signs yet of having brought troops to the south side of Richmond. I will have Petersburg secured, if possible, before they get there in much force.” This will bring an optimistic response from the president: “I begin to see it. You will succeed. God bless you all.” In the North Atlantic, the warship USS Kearsarge arrives in the waters off Cherbourg, France, where CSS Alabama has just arrived for a refit. On board Alabama, Raphael Semmes immediately sends for one hundred tons of coal and prepares to go out and engage his pursuer.33

JUNE 15, 1864: The Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (abolishing slavery), which the U.S. Senate approved on April 8, falls thirteen votes short of passing the House of Representatives by the required two-thirds majority. Congress does finally pass legislation granting equal pay to black soldiers, some of whom have, for many months, been refusing to accept any pay until the inequity was rectified. Retroactive to January 1, 1864, the legislation does not, however, apply to all of the nation’s black soldiers; it covers only those who were free as of April 19, 1861. Tens of thousands of ex-slaves in the U.S. Army are thus excluded from this remedial measure. Efforts on their behalf will continue (see March 3, 1865). In Virginia, General Lee sends one infantry division to reinforce P. G. T. Beauregard, who is currently both defending Petersburg and keeping Benjamin Butler’s Union Army of the James bottled up on Bermuda Hundred with only fifty-four hundred troops. Yet the Federal units that are arriving at Petersburg’s defenses do not know that Beauregard’s force is so small, and, like Grant’s entire army, they are wary and exhausted by their experiences from the Wilderness through Cold Harbor. Though today they begin a series of attacks on the city’s defenses, the assaults will not be sufficiently forceful or coordinated to breach the Confederates’ inner lines. The attacks will, however, increase by nearly ten thousand casualties the “butcher’s bill” that the Union has been paying during this costly campaign. “Yesterday afternoon another horrid massacre of our corps was enacted,” Colonel Rufus Dawes, of the Sixth Wisconsin, will write to his wife on June 18. “It is awfully disheartening to think we have Generals who will send their men to such sure destruction.”34

This color plate from History of the Brooklyn and Long Island Fair, February 22, 1864, published that same year, illustrates the elaborate and patriotic nature of the fund-raising “sanitary fairs” sponsored by individual chapters of the United States Sanitary Commission. On June 16, 1864, President Lincoln praised these efforts when he spoke at the Great Central Sanitary Fair in Philadelphia.

The Copperhead Party.—In Favor of a Vigorous Prosecution of Peace! Wood engraving published in Harper’s Weekly, February 28, 1863. Distress over the “butcher’s bill” of casualties suffered by Federal troops during Grant’s Overland Campaign lent strength to the arguments of Copperheads eager to make peace with the Confederacy—perhaps even at the cost of the Union itself.

JUNE 16, 1864: “War at the best, is terrible, and this war of ours, in its magnitude and in its duration, is one of the most terrible,” President Lincoln says, in a speech at the Great Central Sanitary Fair in Philadelphia. “It has carried mourning to almost every home, until it can almost be said that the ‘heavens are hung in black.’ ” After praising the “benevolent labors” of the men and women of the Sanitary Commission, its sister organization, the Christian Commission, and the soldiers these organizations assist, Lincoln addresses the oft-asked question, when will the war end? “Speaking of the present campaign, General Grant is reported to have said, I am going through on this line if it takes all summer. This war has taken three years; it was begun or accepted upon the line of restoring the national authority over the whole national domain, and for the American people, as far as my knowledge enables me to speak, I say we are going through on this line if it takes three years more.”35

JUNE 17, 1864: Volatile materials explode at the Federal arsenal in Washington, igniting a conflagration. “The scene was horrible beyond description,” the capital city’s Daily National Intelligencer will report. “Under the metal roof of the building were seething bodies and limbs, mangled, scorched, and charred beyond the possibility of identification…. The square in front of the Arsenal gate presents a most distressing spectacle…. Sisters, husbands, and fathers are there waiting for sisters, wives, and daughters. The anxiety and sorrow exhibited is beyond all description.” As was the case with a similar accident the previous year in Richmond, where more than sixty people died, most of the twenty-one people killed at the Washington Arsenal are women who had entered the workforce to assist in the war effort.36

JUNE 18, 1864: Federal troops under David Hunter probe the Confederate defenses at Lynchburg, Virginia, and find that John C. Breckinridge’s troops have been reinforced by the Army of Northern Virginia corps under Jubal Early that Lee has sent to counter the Union threat in the Shenandoah Valley (see June 11–12, 1864). In the evening, Hunter, deciding a full-scale assault will be unsuccessful given the reinforced Confederate garrison, begins to withdraw his men. Early and his troops will soon be in pursuit, eventually chasing Hunter completely out of the Shenandoah Valley. The route to Northern territory will thus lie open. At Petersburg, Virginia, a series of frontal assaults on the city’s defenses having failed (see June 15, 1864), the 110,000-man Army of the Potomac begins digging in to besiege that crucially important railroad hub less than twenty-five miles from Richmond. Morale among Grant’s battered and exhausted troops is at a low ebb (and thousands of these exhausted veterans, having reached the end of their three-year enlistment, are leaving the ranks). But war-weariness isn’t confined to the trenches. At home on sick leave, Union general John H. Martindale writes to Major General Benjamin Butler that there is “great discouragement over the North, great reluctance to recruiting, strong disposition for peace.” The price of gold rises, reflecting the pessimism of Northern financial markets. With casualty rolls listing 65,000 Federal soldiers killed, wounded, or missing since the Overland Campaign began on May 4, Democrats are denouncing Grant as a “butcher.” (Confederate casualties, some 35,000, constitute approximately the same percentage of their smaller force.)37

JUNE 19, 1864: A host of civilians observe from the shoreline cliffs of Cherbourg, France, as CSS Alabama battles USS Kearsarge in the war’s greatest ship-to-ship combat in open seas. Circling and firing, the two vessels draw closer together, with Kearsarge taking the offensive. Outgunned and not yet repaired and refitted, Alabama very quickly suffers critical damage. “Our decks were now covered with the dead and the wounded,” Semmes’s executive officer, Lieutenant John McIntosh Kell, will report, “and the ship was careening heavily to starboard from the effects of the shot-holes on her waterline.” Semmes is forced to strike his colors in order to rescue the wounded before his ship sinks. Nine Alabama crewmen are killed and thirty are wounded; but Semmes and some of his officers manage to escape to England aboard the yacht of wealthy Englishman John Lancaster, who had sailed out to observe the encounter. “[T]he Alabama, our pride & our hope has been sunk off Cherburgh,” North Carolina’s Catherine Edmondston will write in her diary on July 14. “Not a vestige of the Alabama fell into the hands of the Victors! Everything went down & she has left only her fame behind her.”38

JUNE 22, 1864: Seeking to cut the Confederates’ supply lines and extend Union lines, Grant dispatches two Union cavalry divisions under Brigadier General James H. Wilson and Brigadier General August Kautz on a raid against the Southside Railroad, while three infantry corps push south and west toward the Weldon railroad. The infantry corps almost immediately run into trouble. Lee’s Confederates exploit a gap in their lines to shatter one division and threaten others before the Federals manage to regroup. The day’s fighting costs them twenty-four hundred casualties, including seventeen hundred prisoners. The cavalry will have greater success—for a while. Although in the course of a week they will destroy sixty miles of railroad track (which will be quickly repaired), in doing so, they excite the attentions of Wade Hampton’s Confederate cavalry and three of Lee’s infantry brigades. Outnumbered and nearly surrounded, Wilson and Kautz will be forced to burn their wagons and leave artillery and their wounded behind to escape total disaster. While these events are unfolding, General Grant meets with President Lincoln at City Point, Virginia. The president will tour the Petersburg lines on horseback and then, with Grant, travel by boat to meet with Major General Butler before returning to Washington, tired but optimistic, having been impressed by Grant’s quiet confidence.39

The Union music broadside Johnny’s Prayer! and the cover of the 1864 Confederate song Short Rations shine satirically humorous lights on the subject of army food. Despite copious complaints, Federal soldiers were comparatively well fed, but lack of adequate, nourishing rations became a serious problem for many Rebels.

JUNE 23, 1864: Having chased David Hunter and his Federal troops into West Virginia (see June 18, 1864), Jubal Early turns his men northward. Some thirteen thousand Confederates begin marching through dust and scorching heat down the now undefended Shenandoah Valley toward the Potomac River and Union territory. Low on food, the troops chant “bread, bread, bread” when their officers ride by. But, despite their hunger, they keep on going.40

JUNE 24, 1864: “Carpenter, the artist, who is painting the picture of ‘Reading the [Emancipation] Proclamation’ says that [Secretary of State William H.] Seward protested earnestly against that act being taken as the central and crowning act of the Administration,” President Lincoln’s secretary, John Hay, notes in his diary.

[Seward] says… the formation of the Republican Party destroyed slavery; the anti-slavery acts of this administration are merely incidental. Their great work is the preservation of the Union, and in that, the saving of popular government for the world. The scene which should have been taken was the Cabinet Meeting in the Navy Department where it was resolved to relieve Fort Sumter. That was the significant act of the Administration. The act which determined the fact that Republican institutions were worth fighting for.41

JUNE 25, 1864: At Petersburg, Virginia, Union lieutenant colonel Henry Pleasants, a prewar civil and mining engineer, embarks on a project he has suggested and Army of the Potomac Ninth Corps commander Major General Ambrose Burnside has approved: with men of the Forty-eighth Pennsylvania Infantry, a regiment comprising many experienced coal miners, he begins digging a tunnel that will end under the Confederate lines.42

JUNE 27, 1864: Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase nominates Maunsell Field to be assistant treasurer of New York. Though he has been cautioned by President Lincoln to appoint a qualified individual approved by prominent New York Republicans, Chase has chosen a wholly unqualified crony. This is one of many posts Chase has been filling with people who might be useful to him in what President Lincoln, with some amusement, once called, “Chase’s mad hunt after the presidency.” In Georgia, Major General William T. Sherman, now within thirty miles of Atlanta but still frustrated by Joseph Johnston’s reluctance to commit his Confederates to battle, orders his men to assault the entrenched center of Johnston’s army at Kennesaw Mountain. Trying to advance uphill in hundred-degree heat, the Union troops are repulsed at great cost. Reports of the defeat will increase the frustration building on the Union home front. In the South, morale will soar. An Atlanta paper predicts that Sherman’s army will soon be “cut to pieces.”43

Kennesaw’s Bombardment, 64. Pencil, Chinese white, and black ink wash drawing by Alfred R. Waud, 1864. Major General William T. Sherman’s attack at Kennesaw Mountain, Georgia, was a costly failure that raised civilian morale—in the Confederacy.

Miss Kate Chase (1840–1899), between 1855 and 1865. The daughter of Lincoln’s ambitious secretary of the treasury, Salmon P. Chase, the bright, attractive, and vivacious Kate served as her father’s hostess, confidante, and ally in his unsuccessful quest for the presidency. “Diplomats and statesmen felt it an honor to be her guests,” one reporter wrote of her exceptional skills as a Washington hostess.

Salmon P. Chase (1808–1873). Photograph by the Brady National Photographic Art Gallery, between 1860 and 1865.

JUNE 28, 1864: On the day he signs congressional legislation that finally repeals the Fugitive Slave Law, the president also sends a note to Secretary of the Treasury Chase regarding Chase’s nomination of the unqualified Maunsell Field the previous day: “I can not, without much embarrassment, make this appointment,” the president writes, and asks that Chase submit another name. This directive from the chief executive stings Chase’s considerable ego, an aspect of the secretary’s personality that sharp-tongued Radical Republican Senator Benjamin Wade has remarked upon in his singularly pithy fashion: “Chase is a good man, but his theology is unsound,” Wade has said. “He thinks there is a fourth Person in the Trinity, S. P. C. [Salmon P. Chase].”44

JUNE 29, 1864: Having maneuvered successfully to solve the crisis that his appointment of Maunsell Field has caused among New York Republicans (by asking the man Field was to have replaced to serve some months longer), Treasury Secretary Chase then goes one step too far. Convinced that he is irreplaceable, he seeks to confirm his value as a cabinet officer and assert his right to nominate whomsoever he chooses by submitting his resignation—something he has done, for equally manipulative reasons, three times before. Lincoln, however, understands perfectly well what Chase is truly up to and, after three years, he has had enough of the secretary’s machinations. “Your resignation of the office of Secretary of the Treasury, sent me yesterday, is accepted,” he will write Chase June 30. “Of all I have said in commendation of your ability and fidelity, I have nothing to unsay; and yet you and I have reached a point of mutual embarrassment in our official relation which it seems can not be overcome, or longer sustained, consistently with the public service.” Chase’s departure will alarm many in the Union capital—until Lincoln finds a perfect replacement, Republican senator William Pitt Fessenden, chairman of the Senate Finance Committee. Fessenden’s appointment will be confirmed on July 1.45

JULY

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

Invasion of Maryland, 1864: Driving off Cattle and Plunder Taken from the Farmers by Early’s Cavalry. Wood engraving from a sketch by Edwin Forbes, published in American Soldier in the Civil War: A Pictorial History, 1895. Making their way toward Washington and on their return, Early’s Confederates sought both sustenance and revenge for damage Union troops under David Hunter had done in the Shenandoah Valley.

JULY 2, 1864: Congress passes the Wade-Davis Bill, which stipulates certain conditions that seceded states must fulfill before rejoining the Union. President Lincoln views these as retaliatory against the South and a refutation of his own more moderate approach to reconstructing the Union. The president’s pocket veto of the bill [failure to sign it within the constitutionally mandated ten days] will underline the growing rift between Lincoln and congressional Radical Republicans over Reconstruction policy. Reacting to the veto, the sponsors of the bill, Senator Benjamin F. Wade and Representative Henry Winter Davis, will issue a manifesto calling the president’s action a “studied outrage upon the legislative authority of the people.”46

JULY 4, 1864: President Lincoln signs into law a repeal of certain exemption clauses of the Enrollment [Draft] Act of 1863, including the provision allowing payment of a commutation fee of $300 (“blood money” to its many opponents) instead of being drafted. On the other end of Pennsylvania Avenue, Congress passes the Pension Act of 1864, which, among other provisions, allows special, if limited, monetary compensation to those who have been blinded or who have lost both arms or both legs during their wartime service. In Richmond, newspapers print a roster of more than six hundred recaptured slaves and ask their owners to reclaim them. At Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, Jubal Early’s hungry Confederate troops, still heading north (see June 23, 1864), occupy the heights around the town, displacing Union troops. “The Yankees made a great preparation for a July [Fourth] dinner,” one delighted Confederate soldier will write, “so we had the pleasure of eating it for them.” Early will not attempt to take the well-fortified town and Union arsenal, however. The following day, his men will begin crossing the Potomac River into Maryland—spurring alarmed Union officials to call for twenty-four thousand Maryland, New York, and Pennsylvania militia to help defend against this third Confederate incursion into Union territory.47

JULY 5, 1864: With Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry still posing a major threat to his supply lines (see June 10, 1864), William T. Sherman has ordered Major General Andrew J. Smith to “follow Forrest to the death, if it cost 10,000 lives and breaks the Treasury.” Today, Smith leads fourteen thousand infantry and cavalry out of La Grange, Tennessee, and toward Forrest’s base in north Mississippi. On their way, the Union force will wreck everything they find that might be useful to the Confederate military. In Canada, an obscure U.S. peace advocate named W. C. Jewett has been meeting with Confederate emissaries who are ostensibly seeking peace but who are, in truth, more interested in seeing Lincoln defeated in the forthcoming presidential election. Today, Jewett writes to an influential acquaintance, Horace Greeley: “I am authorized to state to you… that two ambassadors of Davis & Co. are now in Canada, with full and complete powers for a peace.” He includes an invitation for Greeley to meet with the “ambassadors,” one of whom, George N. Sanders, has assured him that “the whole matter can be consummated by me, you, them [the ambassadors], and President Lincoln.” Though Greeley is skeptical that the emissaries have the full powers Jewett says that they do (and Greeley is correct, they do not), on July 7 he will forward the note to Lincoln. In his own covering letter, he will remind the president “that our bleeding, bankrupt, almost dying country also longs for peace—shudders at the prospect of fresh conscriptions, of further wholesale devastations, and of new rivers of human blood,” and he begs the president to “submit overtures for pacification to the Southern insurgents.”48

Sisters Lucretia Electa and Louisa Ellen Crossett, probably mill workers, holding weaving shuttles. Photograph by Alfred Hall, September 26, 1859. During the war, textile mills in both the North and the South supplied a range of essential materials to the warring armies. So valuable were their contributions to the war effort that in July 1864 William T. Sherman ordered Georgia mill workers transported to Union territory to deprive the Confederacy of their skills.

Sketch of the Battle of Monocacy, Frederick Co. Md. Saturday July 9th, 1864. Color map by Jedediah Hotchkiss, included in his Report of the Camps, Marches and Engagements, of the Second Corps, A.N.V. and of the Army of the Valley Dist., of the Department of Northern Virginia; during the Campaign of 1864, December 1864.

Major General Lewis (Lew) Wallace (1827–1905), USA. A veteran of the Mexican War and a prewar lawyer and politician, Wallace commanded the patchwork Union force that dueled with Jubal Early’s Confederates at the battle of Monocacy.

JULY 6, 1864: Under orders from William T. Sherman, Brigadier General Kenner Garrard burns the cotton and textile mills of Roswell, Georgia, after discovering that the mills, operating under the neutral French flag, have been supplying rope, tent cloth, and material for uniforms to the Confederate army. Some four hundred Roswell mill workers (all women), and other female and male workers from a nearby town, are transported, via several intermediate stops, to Indiana to “prevent them,” as Sherman says, “from renewing their efforts on behalf of the Confederacy.” Very few of these unwilling deportees will ever find their way back to Georgia; some will settle in the North; others will die there.49

JULY 9, 1864: Having driven on after his defeat at Kenne-saw Mountain, William T. Sherman has outflanked Joseph Johnston and pushed the Confederates back to a position only four miles from downtown Atlanta. Progress has been slow thus far, and the road ahead promises to be even more difficult. “The whole country is one vast fort,” Sherman writes to General Henry Halleck, “and Johnston must have at least fifty miles of connected trenches, with abattis [field defenses] and finished batteries.” Despite these extensive fortifications, with the large Union army at their gates, citizens of Atlanta begin leaving. Meanwhile, President Davis, increasingly distressed at what he deems Johnston’s insufficient aggressiveness against the encroaching Yankees, sends his military adviser, Braxton Bragg, to Georgia on a fact-finding mission; Bragg will recommend to the president that Johnston be replaced. At the Monocacy River near Frederick, Maryland, Jubal Early’s thirteen thousand Confederate troops, now heading toward Washington, DC, meet a hastily assembled Federal force led by Major General Lew Wallace (who will achieve postwar literary fame with his novel Ben-Hur). Except for a contingent of battle-hardened troops (the vanguard of reinforcements Grant has sent north from Petersburg to help protect the capital), the six thousand Federals who engage the invading Confederates at the battle of Monocacy are predominantly inexperienced and no match for Early’s larger force of combat veterans. But before Wallace orders his men to withdraw, his troops do manage, at a cost of more than eighteen hundred casualties, to buy valuable time. As Early pushes on toward Washington, his troops do not treat Yankee property gently. Among the dwellings they ransack and destroy is the Silver Spring, Maryland, home of Postmaster General Montgomery Blair. When they begin the same process in the nearby home of Blair’s parents, however, they are stopped by one of their officers, General John C. Breckinridge, toward whom the elder Blairs had acted with great kindness before the war. Breckinridge will leave a note on the elder Blairs’ mantel: “a confederate officer, for himself & all his comrades, regrets exceedingly that damage & pilfering was committed in this house.”50

“We didn’t take Washington, but we scared

Abe Lincoln like hell!”

—LIEUTENANT GENERAL JUBAL A. EARLY, CA. JULY 12, 1864

Major General Horatio G. Wright (1820–1899), USA. In command of the Sixth Corps of the Army of the Potomac, which relieved Washington when the capital was threatened by Jubal Early’s Confederates, Wright respectfully but firmly curbed President Lincoln’s enthusiasm for viewing the enemy at Fort Stevens. After the war, as chief of army engineers, Wright was involved in completing the Washington Monument.

JULY 10, 1864: Federal authorities and the tense people of Washington continue to prepare for unwanted Confederate callers as refugee civilians from outlying areas pour into the capital city. Militia, ambulatory soldiers convalescing in Washington’s hospitals, and government clerks are armed and sent to the forts defending the capital. President Lincoln, who remains an island of calm in this furious sea of activity, takes time from pressing military matters to wend through the streets in an open carriage with Secretary of War Stanton, in an effective effort to prevent panic. Morale rises considerably when the main body of the reinforcements Grant has dispatched from Petersburg, Major General Horatio Wright’s Sixth Corps, arrives in the city. Crowds rush to the wharves to cheer the blue-coated soldiers as they debark from their naval transports.51

JULY 11–12, 1864: Now on the outskirts of Washington, within sight of the U.S. Capitol’s recently completed cast-iron dome, Jubal Early and his thirteen thousand Confederates survey the city’s fortifications, which Early will later report are “exceedingly strong.” But having come this far, he refuses to withdraw without militarily thumbing his nose at the enemy. He sends a detachment to attack Fort Stevens, only five miles from the White House, and they keep its defenders busy for two days. On both, the U.S. commander in chief is present, evincing, as Horatio Wright will report, “a remarkable coolness and disregard of danger.” Too great a disregard, for some: when Lincoln, wearing his trademark stovepipe hat, keeps popping up to get a good look at the Confederates over the defenses, an irritated young officer (and future U.S. Supreme Court justice), Captain Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., not realizing who the offending civilian is, shouts, “Get down, you damn fool, before you get shot!” General Wright expresses his own concern for the chief executive’s safety by respectfully threatening to have Lincoln removed under guard if he doesn’t stop exposing himself to enemy fire. “In consideration of my earnestness in the matter,” Wright will report, “[Lincoln] agreed to compromise by sitting behind the parapet instead of standing upon it.” The danger is very real; some nine hundred men on both sides are killed or wounded in the fighting around Fort Stevens before the irascible Early withdraws toward the Shenandoah Valley, declaring to one of his officers (with only partial accuracy), “We didn’t take Washington, but we scared Abe Lincoln like hell!”52

Washington, D.C., and Forts. Color map by R. K. Sneden, circa 1863. Fort Stevens, where President Lincoln came under Confederate fire, can be seen in the upper right of the map.

Confederate General John Bell Hood. Pencil drawing on olive paper by Alfred R. Waud, between 1862 and 1865. Known for his aggressive leadership, Hood (1831–1879) was appointed by President Davis to replace General Joe Johnston at Atlanta, as William T. Sherman’s Federals closed in on the city.

JULY 14, 1864: At Tupelo, Mississippi, eight thousand Confederates under Lieutenant General Stephen D. Lee and Major General Nathan Bedford Forrest engage the fourteen-thousand-man Union force William T. Sherman dispatched to smash Forrest (see July 5, 1864). Confederate assaults on Andrew Smith’s Federals are disjointed, however, and the Union troops repel them, inflicting many casualties, including Forrest, who is wounded. Finally, Lee orders a withdrawal. Although Sherman will not be happy that Smith fails to follow and destroy the Rebel force, Smith’s victory at the battle of Tupelo does at least give Sherman temporary relief from the fear that Forrest will sever his railroad supply line.53

JULY 17, 1864: “As you have failed to arrest the advance of the enemy to the vicinity of Atlanta, far in the interior of Georgia, and express no confidence that you can defeat or repel him,” President Davis writes to General Joseph Johnston, “you are hereby relieved from the command of the Army and Department of Tennessee.” Following the recommendation of his military adviser, General Braxton Bragg (see July 9, 1864), Davis replaces Johnston with General John Bell Hood. The action will stir controversy in the Confederacy but will please General Sherman, who believes that Hood will come out and fight in the open, something Johnston would not do.54

JULY 18, 1864: President Lincoln issues a new call, for five hundred thousand men. Coming just after Jubal Early’s raid into Maryland, and in the midst of the costly stalemate in Virginia and Sherman’s slow progress at Atlanta, it is an unpopular plea that sets his prospects for reelection in November even lower. In Niagara Falls, Canada, editor Horace Greeley (who will be joined in two days by Lincoln’s secretary, John Hay) opens negotiations with Confederate agents Clement Clay and James Holcombe (see July 5, 1864). Greeley and Hay will convey to the agents a presidential safe conduct for travel to Washington to discuss peace, as long as the proposition conveyed by the agents, Lincoln states in the safe conduct, “comes by and with an authority that can control the armies now at war against the United States,” and providing the peace under discussion guarantees “the integrity of the whole Union, and the abandonment of slavery.” But, as Greeley had suspected, the agents are not empowered to negotiate—and the Davis administration is only prepared to discuss a peace that will maintain Confederate independence and slavery. The failure of this Canadian encounter will become a potent piece of anti-Lincoln propaganda.55

JULY 20, 1864: The new Confederate commander at Atlanta, General John Bell Hood, fulfills William T. Sherman’s expectations (and those of President Davis) and launches an attack on Major General George H. Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland, beginning the battle of Peachtree Creek. Led by Lieutenant General William J. Hardee, the spirited Confederate assault lacks coordination and fails in the face of equally spirited Union resistance. The Confederates pay a high price for this failure: 4,796 of Hardee’s 19,000-man force are killed or wounded versus 1,710 of the 21,000 Federal soldiers engaged.56

A scene from The Myriopticon: A Historical Panorama of the Rebellion, manufactured by Milton Bradley & Co. before 1890. Turning the wheel inserted in the box changes the scenes and gives viewers a primitive “motion picture” account of the Civil War. Here, an anonymous Union officer succumbs to enemy fire, but his men continue their assault—something that happened during the battle of Atlanta, a Union victory despite the death of Major General James B. McPherson.

Major General James B. McPherson (1828–1864), USA. Steel engraving published in Commanders of the Army of the Tennessee, 1884. Regarded as one of the most promising young officers in the army after his 1853 graduation from West Point, McPherson proved to be an excellent wartime battlefield commander. His death was deeply mourned by his men, and by his friend and commanding officer, William T. Sherman.

Diagram of the tunnel dug by Union troops led by Lieutenant Colonel Henry Pleasants. Illustration in “The Tragedy of the Crater,” published in Century magazine, volume 34, 1887.

JULY 22, 1864: Undaunted by his army’s failure at the battle of Peachtree Creek, General John B. Hood launches another attack, this time focusing his efforts on the Army of the Tennessee, led by Major General James B. McPherson, Hood’s former West Point roommate. Hitting McPherson’s men when they are less than three miles from the city, Hood ignites the battle of Atlanta, a day of fierce fighting that badly shakes the Federals; but it does not break them—even after the Army of the Tennessee loses its commander. Riding forward to deal with a gap in Union lines, McPherson is killed by Confederate skirmishers—becoming one of thirty-seven hundred Federals and eight thousand Confederates killed or wounded in this bloody encounter that is another costly failure for Hood.57

JULY 23, 1864: Lieutenant Colonel Henry Pleasants and the coal miners of the Forty-eighth Pennsylvania Infantry finish the tunnel they have been digging under the Confederate lines at Petersburg, Virginia (see June 25, 1864). Extending 525 feet, the tunnel has two side galleries, which, on June 27, Pleasants and his men will start packing with twenty-five-pound kegs of gunpowder.58

JULY 24, 1864: Having largely eluded the Union troops that followed him from Washington (see July 11–12, 1864), whose pursuit was hampered, General Grant will later report, by “constant and contrary orders… from Washington,” Jubal Early and his Army of Northern Virginia Second Corps rout eighty-five hundred Federals at the second battle of Kernstown, near Winchester, Virginia. Once again, the lower Shenandoah Valley is open to the Confederates and Early heads north, toward the Potomac.59

JULY 28, 1864: At the battle of Ezra Church, outside Atlanta, John B. Hood’s Confederates stop a Union attempt to cut Atlanta’s last railroad supply line—but they suffer 5,000 casualties in the process (versus the Union’s 562). Combined with the losses sustained at the battles of Peachtree Creek and Atlanta, this so weakens Hood’s army that the general will be forced henceforth to remain on the defensive.60

JULY 30, 1864: Brigadier General John McCausland and twenty-six hundred cavalry dispatched from Jubal Early’s force arrive at Chambersburg in southern Pennsylvania with Early’s demand for $100,000 in gold or $500,000 in greenbacks as compensation for property David Hunter’s Union troops destroyed in the Shenandoah Valley (see June 11–12, 1864). After Chambersburg citizens refuse to pay, McCausland’s troopers set fire to the town, destroying some four hundred buildings and leaving nearly three hundred families without homes. Within a few days, General Grant will form a new military force, the Army of the Shenandoah, and place Major General Phil Sheridan at its head. Sheridan’s objectives: first, to destroy Early’s army; second, to destroy the fertile valley’s capacity to be the “Breadbasket of the Confederacy” (feeding among others, Lee’s army at Petersburg and guerrillas operating in the valley). “Take all provisions, forage and stock wanted for the use of your command,” Grant orders Sheridan. “Such as cannot be consumed, destroy,” leaving the area so deprived that “crows flying over it… will have to carry their provender with them.” At Petersburg, Lieutenant Colonel Pleasants’s inspired plan for breaching Confederate defenses (see June 25 and July 23, 1864) reaches its climax as four tons of gunpowder placed in the finished tunnel explodes in a lethal fountain of red sand, earth, and Rebel fortifications. The blast kills or wounds nearly three hundred Confederates, creates a huge gap in the Petersburg defenses, and gouges a crater, 30 feet deep and 170 feet long, in the ground over which Union troops are set to attack. That assault devolves into a misdirected muddle during which many Federal troops tumble into the crater rather than go around it and are trapped in murderous Confederate musket and mortar fire. The subsequent Rebel counterattack is one of the earliest occasions “on which any of the Army of Northern Virginia came in contact with Negro troops,” Confederate brigadier general Porter Alexander will later write, “and the general feeling of the men toward their employment was very bitter.” The fighting turns vicious. “This day was the jubilee of fiends in human shape, and without souls,” one Rebel soldier will say. Federal casualties are high, particularly among black soldiers, some of whom are killed as they try to surrender. Grant will call the abortive battle of the Crater “the saddest affair I have witnessed in the war.”61

Colonel Delevan Bates at “The Crater” (Petersburg). Illustration in Deeds of Valor, Volume 1, 1901–1902. Commander of the Thirtieth U.S. Colored Infantry, Bates was wounded in the head as he led his troops into what was described as “a perfect maelstrom of rebel lead.” Ten officers and 212 enlisted men of this regiment alone were killed, wounded, or taken prisoner during the bitter fighting at the Crater.

AUGUST

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31

Abraham Lincoln. Memorandum, August 23, 1864. Convinced that it was probable that he would be defeated in the November 1864 presidential election, Lincoln wrote this pledge, folded it, and had his cabinet sign the memorandum without reading it.

AUGUST 1, 1864: The Confederate legislative act of February 17, 1864, which renewed President Davis’s authority to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, expires. Despite intensifying Union pressure and the growing influence of Southern peace societies, the Confederate Congress will never again give Davis the authority to suspend the writ.62

AUGUST 4, 1864: The London Times carries a dispatch from its Richmond-based correspondent, Francis Lawley, who has lately been impressed by the relative calm of the Confederate capital: “If a man were landed here from a balloon after six months’ absence… and told that two enormous armies are lying a few miles off and disputing its possession, he would deem his informant a lunatic…. Richmond trusts and believes in St. Lee as much as Mecca in Mahomet.” Lawley seems to share this faith. Lee, he states, has the initiative “now that his hardy antagonist lay foiled, baffled, and emasculated before him.”63

Lashed to the Shrouds—Farragut Passing the Forts at Mobile, in His Flagship Hartford. Color lithograph published by L. Prang & Co., 1870–1871. The highest-ranking officer in the Union navy during the war, Farragut led his fleet to victory through a minefield and intense Confederate fire, closing the port of Mobile to Rebel shipping.

AUGUST 5, 1864: Admiral David Farragut, Union hero at New Orleans and veteran of Mississippi River combat, again reflects his personal motto of “Audacity, still more audacity, always audacity” as he leads his Union fleet of fourteen wooden ships and four ironclads into Mobile Bay. Serving Mobile, Alabama, the last blockade-running port in the Gulf of Mexico east of Texas, the bay is guarded by the formidable Fort Morgan and a small naval contingent of three gunboats and the ironclad CSS Tennessee, captained by Admiral Franklin Buchanan (see March 8, 1862). It is also laced with underwater mines, called torpedoes. Undaunted, the admiral climbs to a vantage point on a mast of his flagship USS Hartford and, shouting “Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead,” he leads his fleet in a duel with the fort and Buchanan’s Tennessee. At a cost of 145 Union lives, including 93 men on USS Tecumseh, which strikes a torpedo and founders, Farragut’s fleet takes the fort and the bay, closing the port of Mobile to all shipping (though Mobile itself will continue to hold out; see March 24–25, 1865).64

AUGUST 19, 1864: President Lincoln meets with Frederick Douglass, chiefly concerning the effects the current “mad cry” for peace might have on people still held as slaves. The meeting is a revelation for Douglass, who has often been critical of the president’s actions. “The President is a most remarkable man,” he will report. “I am satisfied now that he is doing all that circumstances will permit him to do.” For his part, the president will tell Union chaplain and commissioner of contrabands John Eaton that, “considering the conditions from which Douglass rose, and the position to which he had attained, he was… one of the most meritorious men in America.”65