The United States in 1865 was far different from the country of 1860. Whole areas of the South were in ruins and fully one-quarter of its military-age white men were dead. The region was occupied by Union troops, its economy was shattered, and the potent political influence the South had wielded before the war was gone. North and South, the Civil War took more American lives than all other conflicts combined, through Vietnam.146 It had shaken assumptions, shattered illusions, and added fuel to the fires of social reform movements—from suffrage to labor unions—that had been kindled in the prewar North. In the South, it also gave birth to the gripping mythology encompassed in the term “Lost Cause.”

Four million Americans who had been considered property in 1860 were now recognized as human beings and American citizens. But that fact had not erased prejudice; nor would measures taken to assist in the education and integration of these freedmen and women into the larger society, and to erase barriers faced by all people of color in most parts of the nation, be as persistent or effective as their advocates hoped.

Even before the Civil War ended, violence erupted in the South against the freedmen and those who tried to help them. Difficulties escalated during the period of Congressional Reconstruction (1865–1877), as Radical Republicans overrode President Johnson’s vetoes of Reconstruction legislation, and that legislation sparked violent reaction among many Southern whites—particularly ex-Confederates, planters, and other men of influence and power. These men were determined to “redeem” their states from Republican influence (and from what they termed “Negro rule,” something that never existed), and they succeeded. By 1877, all eleven Confederate states had been readmitted to the Union, and white conservative Democrats controlled those state governments. As these “redeemed” Southern states continued to recover from the ravages of war, the limited progress that some black Southerners had made toward equality during the immediate postwar years was largely reversed.

Terror was one potent weapon in this process of white “redemption”; secret societies, most prominent among them the Ku Klux Klan, employed tactics ranging from psychological intimidation to arson, whippings, and murder to create a climate in which black citizens feared to exercise their rights and sympathetic whites feared to help them. In the late 1860s, Klansmen murdered white Republican congressman James M. Hinds of Arkansas, three South Carolina state legislators, and some two hundred African Americans in one Louisiana parish alone. Louisiana and Georgia went to the Democrats in the 1868 presidential election (won by Republican Ulysses S. Grant) because Republican voters had been so intimidated that they stayed away from the polls. It would be more than a century before the promises of equal rights embodied in the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution would begin to be fully realized for people of color in the South and throughout the country.147

Yet the Civil War did resolve the two primary issues that sparked it: It eradicated slavery in the United States. And it preserved the unique American experiment in democracy—“government of the people, by the people, for the people”—answering unequivocally the question articulated by James W. Grimes, U.S. senator from Iowa, as the first Southern states were attempting to fulfill their threats to dismember the Union so painfully birthed in hope and promise less than a century before. “The question before the country, it seems to me, has assumed gigantic proportions,” Grimes wrote, in January 1861. “The issue now before us is, whether we have a country, whether or not this is a nation.”148 The answer—inscribed in the blood and sacrifice of the people on both sides of this terrible conflict, and never thereafter challenged—was yes.

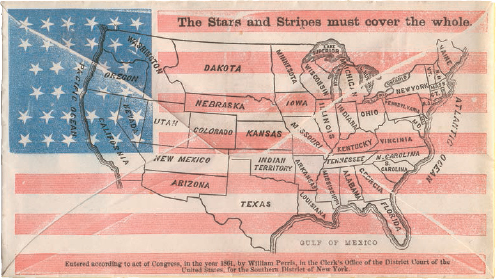

The Stars and Stripes Must Cover the Whole. Published in 1861, the year Iowa senator James W. Grimes asked “whether we have a country, whether or not this is a nation,” this envelope reflects the ultimate answer, achieved at a terrible cost.