Bogotá, a city once ravaged by decades of military, socioeconomic, and political strife, has become a model for a new approach to security. This significant change provides two distinct understandings of what can function as sources of security. One is a conventional understanding of security that highlights the importance of physical structures and institutions directly charged with creating security. The other is an alternative that emphasizes the role of bogotanos as citizens, public transport systems, parks, and neighborhood groups can develop urban capabilities that provide a more secure environment than walls, checkpoints, and security guards. Bogotá provides examples of both side by side.

This distinction also might be conceptualized in terms of security, either as a good that can grow when communally shared or as an expensive, often privately purchased commodity afforded to only a few. Extending this line of reasoning, the privatized commodity-based approach to security tends to result in the formation of enclaves and the compartmentalizing of cities, whereas the basis of a communal approach to security is the idea of mobility. To build shared security, all city dwellers must be enabled to move about their city comfortably. The aim is to create a virtuous circle whereby when bogotanos enjoy the benefits of transportation, their security is increased as places once desolate are given life. This increased sense of security encourages additional movement that is less constrained by fears of victimization.

This chapter starts with an overview of the context and history of the security situation in Colombia and Bogotá and a review of the distribution of crime in Bogotá. The purpose is to illustrate how security has developed into a commodity in Colombia, as well as the consequences of this process. We then examine the package of reforms that aim to reverse this process through a communal approach to security. Finally, we discuss how all the reforms play a pivotal role in the development of Bogotá’s distinct security framework. On the one hand is the implementation of tougher and more sophisticated measures to control organized crime, and on the other hand is the promotion of communally based approaches that strengthen not only citizenship security but also coexistence and well-being.

We conclude that Bogotá reflects a noteworthy case of how a city has built urban capabilities to deal with conflict and crime, although it still faces challenges, including new scenarios to come from the Colombian postconflict era.

The Colombian Context and the Configuration of a Multilayered Conflict

To understand Bogotá today it is important to take into account the recent history of security and safety in Colombia. Despite its resurgence as a country, Colombia still carries the stigma that it earned through the toxic mixture of narco traffickers and insurgent forces that turned the streets of every major Colombian city into battlegrounds between the mid-1970s and the early 2000s.

Background Factors: The Wars

Since the conflict between left-wing groups and the Colombian military began in 1958 (later incorporating conflict between narco traffickers and the state), more than 177,000 civilians have been murdered, 31,000 police and military members have been killed, and more than 27,000 have been abducted (Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica 2012). The kidnapping problem was so bad that the BBC named Bogotá the “kidnap capital of the world” (BBC 2001). In total, 7.38 million individuals have been victims of the conflict that saw Colombia fight for its survival against insurrectionists and narcotraficantes (Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica 2012). The focus of many of the crimes committed by these two groups were against government employees (e.g., politicians, members of police and military, etc.) and wealthy individuals and prompted the development of elaborate private security systems, closed housing complexes, private security guards, and other security mitigation strategies that reflect a physical separation of the spaces and the people (Gutiérrez 2012).

In parallel with the armed conflict in the 1980s, the increase of narcotráfico (drug trafficking) and the fight against drug cartels represented an open confrontation between organized crime and the public institutions (especially against law enforcement officials) through what was called narcoterrorismo.1 Antidrug activities had expanded rapidly in Colombia after U.S. President Ronald Reagan declared an intensified effort to eradicate drugs because he believed that “Drugs are menacing our society. They’re threatening our values, and undercutting our institutions. They’re killing our children” (Reagan 1986). U.S. support rapidly modernized the Colombian law enforcement system, but emphasis was put on developing state security forces that would be more capable of attacking armed guerrillas and paramilitary forces than in protecting citizens’ security.

The funds from Plan Colombia were directed largely toward law enforcement activity, including the use of herbicides delivered via aerial spraying (Rincón-Ruiz and Kallis 2013). Many farmers found their fields, homes, and drinking water contaminated by the spraying and had no choice but to leave (Beckett and Godoy 2010). These antidrug activities are essential for understanding the broad scope of internal displacement in Colombia, with many of these uprooted individuals ending up in the main cities, such as Bogotá.

In short, the insecurity long felt in Bogotá is the result of many years of violent attacks that have rocked the capital and, indeed, all parts of Colombia for more than fifty years. These include attacks by the left-wing guerrilla group M-19 against the country’s Supreme Court in 1985; bomb attacks on the Departamento Administrativo de Seguridad (DAS) in 1989 ordered by narco cartels; several car bombs detonated in various commercial and political influence zones in the 1990s; and bomb attacks on the police headquarters in 2002. Additionally, the Club El Nogal was attacked by the FARC in 2003, Caracol radio station in 2010, and a mortar attack on the presidential inauguration in 2002.

Such attacks have lessened in recent years but continue, with attacks on police and civilian targets. In the first month of 2018 there were eight terrorist attacks in Colombia, often directed against police and military but also injuring civilians (El País 2018). These repeated victimization and large-scale attacks have left an indelible imprint on the consciousness of bogotanos.

Colombia’s multilayered conflict includes the armed conflict between state security forces and guerrillas groups, the violence perpetrated by drug cartels, the emergence of paramilitary groups, and the actions by organized crime groups. Each of these has fed key aspects of urban development—law enforcement systems, public transport, public spaces, citizenship culture, and more—aimed at the challenges created by forced displacement, housing problems, insecurity, and the making of enclaves.

Moving from Privatized to Community-Based Security?

Bogotá’s efforts to improve its security and civic spaces in the past two decades, pushed through by liberal-minded mayors, have received much attention and praise. This praise stems from the city’s seeming ability to square the circle, that is, to not sacrifice civil liberties for more security. It has promoted security precisely by strengthening democratic values. A focus on a culture of citizenship, the redevelopment of public spaces, and wide-ranging improvements to the transportation systems to connect the people with and through the city—all these aspects illustrate the concept of urban capabilities cited in the introduction to this volume. Through such measures, Bogotá’s urban capabilities were constructed on the basis of democratized public space (transport included) to promote inclusion and to improve the quality of life of all citizens.

Former Bogotá Mayor Enrique Peñalosa outlined this new vision for the city when he said, “An advanced city is not one where even the poor use cars, but rather one where even the rich use public transport” (Peñalosa 2013). In other words, for policies and infrastructure projects geared toward creating security through citizenship to be meaningful, they need to have active impacts on the ways in which Bogotá inhabitants “practice their city.” Indeed, the story of Bogotá’s transformation is largely about the reorganization of transport; that is, the public means provided to move through spaces. It is important to reiterate that mobility is not only a question of convenience but key to a communal approach to security based on the notion that all citizens should be comfortable moving through their city.

The story of Bogotá is one of violence and inequality but also of impressive reform efforts, economic growth, crime reduction, and cultural transformation (Beckett and Godoy 2010). Bogotá is one of the largest capital cities in Latin America and one of the most attractive investment locations in the region (Universidad del Rosario 2014). Institutional, economic, political, and social investments have aimed at improving security and civility at both the national and the local level. The city has witnessed a sharp reduction in crime rates, with particularly dramatic reductions in the homicide rate. In 1993, the homicide rate stood at 80 homicides per 100,000 population but declined to only 14 per 100,00 by 2017, which was well below the 24 per 100,000 for the country as a whole (Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses 2017). Bogotá’s security infrastructure was centered on the making of new public spaces, an innovative public transport system (called Transmilenio), and the development of what one former mayor referred to as a “cultura ciudadana” (culture of citizenship).

However, Bogotá city also faces other issues that challenge the security improvements reported earlier. High levels of economic inequality and a widespread perception of insecurity still plague the city. Bogotá is a highly unequal city located in one of the most unequal countries of the world (UN-Habitat 2010). Such inequality threatens the defense of public interests (citizenship security) and governance at the expense of the benefits of a few powerful elites (Stiglitz 2015; Piketty, 2014). In 2017, 50 percent of Bogotá inhabitants reported that insecurity had risen in the last few years (Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá 2017), whereas 95.2 percent of residents thought they needed to be careful with other people (just 4.1 percent reported that most of the people can be trusted) (World Values Survey 2018). Thus privileged groups that felt insecure still might have reason to seek out privatized ways to deal with their own security, even at the expense of supporting public efforts to invest in an open and inclusive city.

Arguably one of the reasons that Bogotá had such potential to improve its security situation through developing a shared sense of citizenship is precisely because its population is economically so unequal. Put differently, purchasing security privately as a commodity has a long and entrenched history in Colombia for certain segments of the population. The communal approach to security provision is new and relatively fragile but has many potential beneficiaries who are unable to afford sufficient levels of security through private spending. Although it might be difficult to scale up private security efforts such as personal bodyguards, underground parking garages, and large homes, there exists an opportunity to build security through the creation of safe public spaces ruled by prosocial groups instead of law enforcement officials. However, even with significant efforts to improve Bogotá’s transportation system, in 2017 between 54 percent and 78 percent of the population saw public transport—taxi and Transmilenio services—as insecure (see Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá 2017).

The Privatizing of Security: Socioeconomic Inequality

Although we cannot prove that Bogotá’s high levels of inequality (UN-Habitat 2010; Valencia 2015) is a causal factor in its insecurity, large economic inequalities do have an impact resulting in higher rates of violence, poor public health, high incarceration levels, lack of interpersonal trust, education problems, and more (Wilkinson and Pickett 2010). Therefore, although causal relations between economic inequality and security are complex, empirical research shows that inequality is pervasive in areas with insecurity problems (Rufrancos and Power 2013). Inequality is both a challenge for cities and a condition that reshapes them (Sassen 2012).

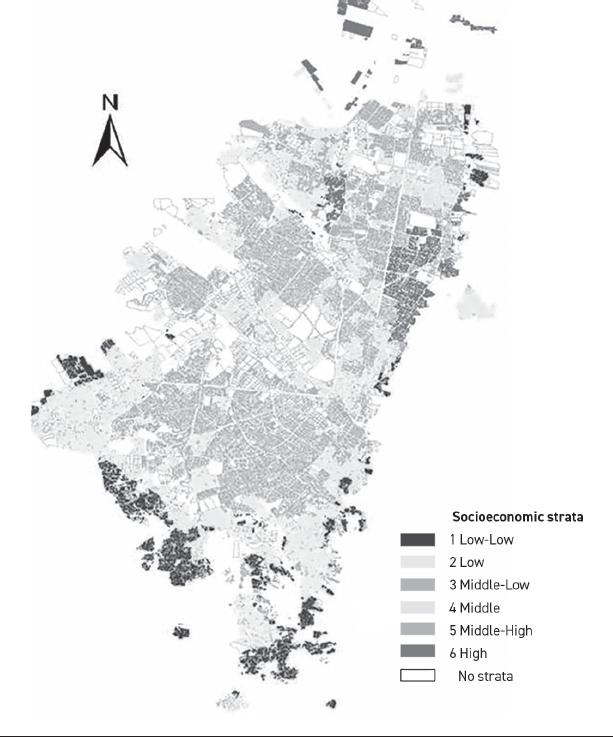

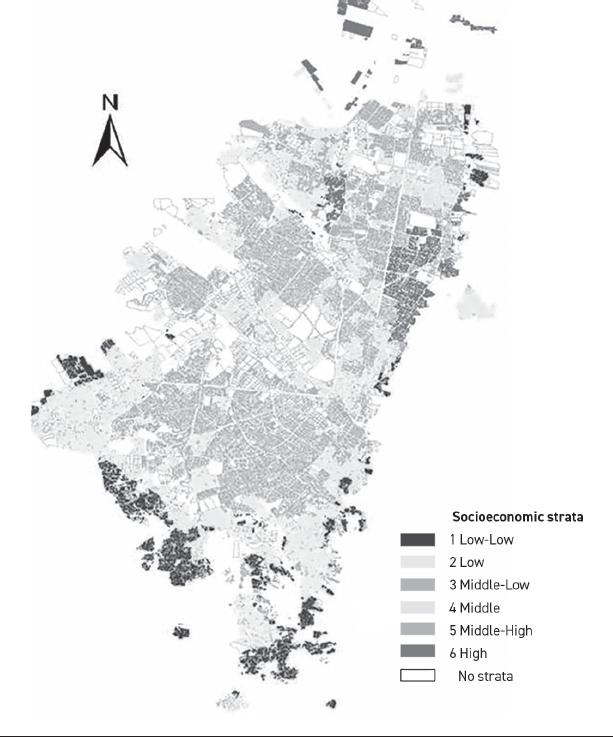

Urban space in Colombia is officially divided into socioeconomic strata to ensure fairness regarding public services (drinking water, electricity, sewage system, gas, and phone) and taxes (DANE 2015). Socioeconomic stratification, based on the costs and settings of housing, divides the city into six levels, ranging from very high to very low (Secretaría Distrital de Planeación de Bogotá 2011). This system cements the link between urban space and economic inequality, with taxes depending on which of the six levels one lives in.

Bogotá is divided into 19 localidades (localities), which are defined by socioeconomic strata. Map 7.1 shows that half of the population and territory of Bogotá is concentrated in the two lowest levels. The highest two levels account for under 5 percent of the population (Secretaría Distrital de Planeación de Bogotá, 2011). These divisions stereotype social classes and can lead to segregation, discrimination, and marginalization (Uribe-Mallarino 2008). Privatized security is an integral part of this mix of policies, habits, and built environments that marks Bogotá’s social texture.

Map 7.1 Socioeconomic stratification in Bogotá.

Source: Secretaría Distrital de Planeación de Bogotá (2018).

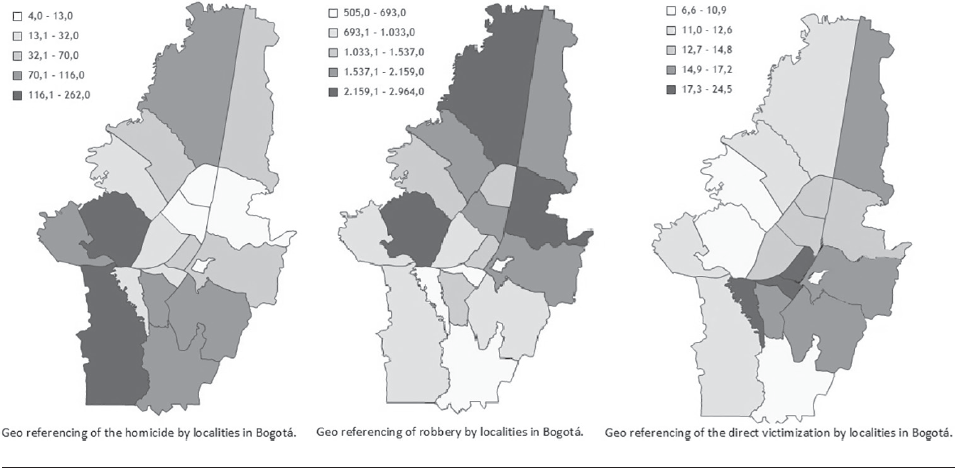

One effect of the division of the city by socioeconomic strata is that criminality is also unevenly distributed in Bogotá. Most homicides are concentrated in the south of the city, home to the poorest neighborhoods; Map 7.2, left side), whereas robbery is more intense in the north and center, home to the richest neighborhoods; Map 7.2, center). Victimization is concentrated in the city’s center and the commercial downtown (Map 7.2, right side).

Map 7.2 Geo-referencing of crime in Bogotá.

Source: Drawn by the authors based on data from Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá (2015).

Although we lack direct empirical evidence correlating socioeconomic conditions with insecurity in Bogotá, polls show that 44 percent of citizens think rising insecurity is caused by socioeconomic conditions and that insecurity has risen, especially in public transport (57 percent) and on streets (45 percent; see Cámara de Comercio de Bogotá 2015).

A Distinct Path: Creating Community-Based Security Through Urban Capabilities

Bogotá’s success in leaving behind the earlier extreme violence is attributed in part to national-level reforms (the law enforcement system and the war against drug cartels; see Casas and Gonzalez 2005; Llorente & Guarín 2013). Also impactful were the measures implemented by Bogotá’s mayors between 1995 and 2013 that focused on the making of a cultura ciudadana (citizenship culture) based on civility, prevention, education, participation, improvements, and promotion of public spaces and mobility (Acero 2013). Because both approaches coexist, it is difficult to establish their respective independent effects on security. Most likely it will be an ideological choice as to which one can be attributed the current successes. However, Bogotá mayors Mockus and Peñalosa are internationally recognized for addressing insecurity with an education and prevention approach that involved the whole community. Promoting respect among citizens, increasing the use of public spaces, and enhancing public transportation to democratize the city were pillars of these mayors’ success.

Key to these reforms was understanding security as a cultural issue. Bogotá’s improved security could not have been achieved through strengthening law enforcement, diminishing socioeconomic inequalities, or modifying laws. It took working on the beliefs, interests, and emotions involved in people’s behavior (Mockus et al. 2012). This project sought to improve citizens’ moral development by emphasizing legality, morality, and culture as part of citizens’ autonomy. It avoided instilling fear of law through monitoring and punishments. Security became a function of the way people relate to one another.

However, the program was not without its shortcomings. Poor citizens were portrayed as living in crime-breeding slums and saw their neighborhoods razed to build parks and new infrastructure. The effort to remove insecurities in Bogotá promoted the idea that fighting crime was akin to defeating terrorism, though such efforts, unsurprisingly, led to the stigmatization of some communities (Zeiderman 2013a, 2013b).

A variety of local reforms helped to create effective law enforcement mechanisms based on the needs of citizens. This included the consejos locales de seguridad (local councils of security) to help improve public accountability and management of security practices. Community policing with neighborhood and problem-oriented aims was implemented and supported by frentes locales de seguridad (similar to a neighborhood watch group) with neighbors supporting local security through solidarity practices. Zonas seguras (small mobile police stations built into a van or bus) were a program to decentralize the security infrastructure away from police stations (Mockus et al. 2012) and to encourage citizens’ cooperation with authorities and participation in the solutions, a process known as responsibilization (Garland 2001). The strategy entails improving relations not only between communities and local authorities but also among citizens through local activities and the recovery of public spaces. It also included tarjetas ciudadanas (citizen cards) to address football hooliganism and general uncivil behavior; for example, “mimes and zebras” to teach how to use public spaces and pedestrian sidewalks, and pico y placa to improve mobility through the promotion of public transport and the restriction of private cars on the road, including carless days—días sin carro. These policies suggest that in Bogotá, mobility is more than just convenience of movement; it is a key part of the city’s communal security.

The core of this program of security through mobility included several integrated transportation policy developments, the most visible of which was the restructuring of the city’s bus system. Improvements in the Transmilenio bus system—which included special lanes for buses, new high-efficiency loading platform areas, and other improvements—enabled the system to carry more than 1.5 million people per day (Gilbert 2006). Although the new system showed great promise and achieved many of its goals for a short time, it is currently in a state of disrepair, plagued by inefficiency and a growing sense of insecurity. By giving all residents the ability to travel in well-functioning public infrastructure, it was hoped that a democratizing effect would support the city’s efforts to reduce incivility and crime (Beckett and Godoy 2010).

Peñalosa, the mayor renowned for invigorating the communal approach to security, was reelected in 2015 for a four-year term and continues the struggle to keep the system functioning as designed. Bogotá is still trying to upgrade the public transport system and is considering implementing an underground metro system.

The strategies implemented in the city combined security and culture concepts using public spaces and transportation. The infrastructure investment was complemented by considerable efforts to promote new practices and relationships between people and the city, which opened a variety of opportunities for change. Future researchers should consider how individuals create narratives about the geographical manifestations of competing modes of security through ethnographic methods.

We have taken a mostly descriptive approach to presenting the complex security situation that characterizes Bogotá. Security is a topic with a long history and many layers in Colombia, and we have worked our way through them from the national down to the local context. In this way we have attempted to make it apparent that Bogotá’s approach to security policy developments break with many long-standing practices. This approach can be described as turn away from a conventional understandings of security as an expensive, often privately purchased commodity in the form of guards, walls, and checkpoints that create enclaves, to a communal approach to security that aims to integrate citizens across divides so that they can give each other security.

The latter approach is tied to public transport and places a shared responsibility on citizens to own and be responsible for themselves. This idea would be considered somewhat radical in most contexts, but is especially significant as a policy development in a city such as Bogotá, which spent more than forty years trying to combat violence through ever-increasing law enforcement activity and is characterized by a high level of inequality.

Although the transportation system at the heart of this reconsidered approach to security languishes due to underfunding, even the moderate success visible in this new approach should encourage all policy makers to consider how they might seek to engender a culture of citizenship to promote security in their own communities. Going forward, the success of these efforts will not be judged on crime rates alone but on the establishment of a communal sense of security that will cast off a half century of victimization and turbulence. Such outcomes will be visible in the economic, cultural, and communal vibrancy of a Bogotá that is accessible to all her citizens.

Note

1. The term narcoterrorismo gained prominence after the 9/11 attacks in the United States as part of an effort to delegitimize FARC insurgents and link them to the wider narrative of terrorism to garner U.S. support for the fight against such groups (Borja-Orozco et al. 2008).

References

Acero, H. 2013. Respuesta al estudio “Colombia: éxitos y leyendas de los ‘Modelos’ de Seguridad Ciudadana: Los casos de Bogotá y Medellín” [Reply to the study “Colombia: successes and myths about the Models of Citizenship Security: the cases of Bogotá y Medellín”]. Accessed on August 14, 2019. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/sites/default/files/Respuesta al estudio de Llorente y Guarin_0.pdf.

Beckett, K., and A. Godoy. 2010. “A Tale of Two Cities: A Comparative Analysis of Quality of Life Initiatives in New York and Bogotá.” Urban Studies 47 (2): 277–301. http://usj.sagepub.com/content/47/2/277.

Borja-Orozco, H. et al. 2008. “Construcción del discurso deslegitimador del adversario: gobierno y paramilitarismo en Colombia” [Building a Discourse to Delegitimize the Opponent: Government and Paramilitarism in Colombia]. Universitas Psychologica 7 (2): 571–84. http://www.scielo.org.co/pdf/rups/v7n2/v7n2a20.pdf.

Casas, P., & P. Gonzalez. 2005. “Políticas de seguridad y reducción del homicidio en Bogotá: mito y realidad” [Policies of security and reduction of homicides in Bogotá: myth and reality], in Seguridad urbana y policía en Colombia, ed. P. Casas, Á. Rivas, P. González, & H. Acero, 236–89 (Bogotá: Fundación Seguridad y Democracia).

——. 2017. “Encuesta de Percepción y Victimización en Bogotá Primer semestre de 2017” [Survey of perception and victimization in Bogotá. First semester 2017]. Accessed on August 15, 2019. http://bibliotecadigital.ccb.org.co/bitstream/handle/11520/19393/Presentación Encuesta de Percepción y Victimización I semestre de 2017.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Garland, D. 2001. The Culture of Control: Crime and Social Order in Contemporary Society. Oxford: Clarendon.

Gilbert, A. 2006. “Good Urban Governance: Evidence from a Model City? Bulletin of Latin American Research 25 (3): 392–419.

Gutiérrez, F. 2012. “Una relación especial: privatización de la seguridad, élites vulnerables y sistema político colombiano (1982–2002)” [A special relationship: privatization of security, vulnerable elites, and the colombian political system]. Revista Estudios Socio-Jurídicos 14 (1): 97–134.

Instituto Nacional de Medicina Legal y Ciencias Forenses. 2017. Forensis 2016. Datos para la vida: Herramienta para la interpretación, intervención y prevención de lesiones de causa externa en Colombia [Forensis 2016: Data for life: Tools for the interpretation, intervention, and prevention of injuries caused by external factos in Colombia]. Bogotá, Colombia: Fiscalía General de la Nación. Accessed on August 15, 2019. http://www.medicinalegal.gov.co/documents/20143/49526/Forensis+2016.+Datos+para+la+vida.pdf.

Llorente, M. V., S. Guarín. 2013. “Colombia: Éxitos y leyendas de los ‘modelos’ de seguridad ciudadana: los casos de Bogotá y Medellín” [Colombia: Successes and myths of the Models of Citizenship Security: the cases of Bogotá and Medellín]. In¿A dónde vamos? Análisis de políticas públicas de seguridad ciudadana en América Latina, ed. C. Basombrío, 169–202. Washington, DC: Wilson Center Latin American Program.

Piketty, T. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rincón-Ruiz, A., and G. Kallis. 2013. “Caught in the Middle, Colombia’s War on Drugs and Its Effects on Forest and People.” Geoforum 46: 60–78.

Secretaría Distrital de Planeación de Bogotá. 2011. “21 Monografías de las localidades. Distrito capital 2011, Bogotá” [21 Monographies of Bogotá localities]. Accessed on September 19, 2019, https://bit.ly/2kQPuQ7.

Stiglitz, J. E. 2015. La Gran Brecha [The great divide]. Madrid: Taurus.

Uribe-Mallarino, C. 2008. “Estratificación social en Bogotá: De la política pública a la dinámica de la segregación social” [Social stratification in Bogotá: From public policies to the dynamics of social segregation]. Universitas Humanística 65(January–June): 139–71.

Wilkinson, R., and K. Pickett. 2010. The Spirit Level. Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger. New York: Bloomsbury.