The Brain and God: Who’s in Charge?

I’m not sure if others fail to perceive me or if, one fraction of a second after my face interferes with their horizon, a millionth of a second after they have cast their gaze on me, they already begin to wash me from their memory: forgotten before arriving at the scant, sad archangel of remembrance.

—Ariel Dorfman, Mascara, 1988

You are with your friend Miss Muxdröözol, the extraterrestrial artist introduced in “Chapter 2: Good and Evil.” Today she is showing you a rather strange collection. You walk down fluorescent corridors filled with gray, wrinkled things stored in formalin-filled jars to prevent decay.

Miss Muxdröözol motions to the brains. “I’ve gone back in time to gather all these.”

You nod as you look at small labels on the jars. Outrageous! On your left are the brains of the Israelites, the postdiluvian patriarchs Abraham and his descendants Isaac, Jacob, and Joseph.1

You turn to Miss Muxdröözol, “This is utter sacrilege. You don’t mean to tell me you have the brains of these famous biblical men?”

“Yes, I traveled back in time to the Mideast about two thousand years before the birth of Jesus. Do not worry. We removed their brains seconds after their death. History was not changed, and the men did not suffer because of my act. Their souls, if they existed, were not affected by what I did to their bodies after death.”

You give a little tap on the jar marked “Abraham.” His cerebrum jiggles like a big, dancing prune. You think about this ancient man. According to the Bible, God had promised Abraham a country especially set aside for him and his descendents. God told him, “I will make you into a great nation.”

You walk a little further, wrinkling your nose at the strange chemical odors. On your right are a few clear pickle jars. You reach for the one marked “Joseph, Son of Jacob,” open it, and drag your fingers lingeringly over his gray-white frontal lobes. Might there be remnants of his genius preserved in his neuronal networks—the time Joseph interpreted Pharaoh’s dreams or the time he forgave his brothers for their sins against him? Could some fossil of his love toward his Egyptian wife Asenath still be trapped within the folds of flesh?

The brain: three pounds of soft matter that can take a split second of experience and freeze it forever in its cellular connections. One hundred billion nerve cells are the architecture of our experience. Is the biblical Joseph still here in the wet organ balanced in your palm? Could we reconstruct his memories? Would Joseph approve such a breach of privacy?

You replace Joseph and glance longingly at some of the other brains in Miss Muxdröözol’s possession: Enoch, Irad, Mehujael, Methushael, Lamech, Adah, Jabal, Zillah. Such exotic-sounding names. She tells you that some of the brains in her collection are perfused with glycerol and frozen to –320 degrees Fahrenheit with liquid nitrogen. She hopes some day to learn from their memories. She refuses to give up hope that memories still reside in the brain cell interconnections and chemistry, much of which is preserved. Maybe she is right. After all, far back in the 1950s, hamster brains were partially frozen and revived by British researcher Audrey Smith. If hamster brains can function after being frozen, why can’t ours? In the 1960s, Japanese researcher Isamu Suda froze cat brains for a month and then thawed them. Some brain activity persisted.

But what if there is an afterlife? You bang on the giant thermos bottle containing Moses’s brain, causing the brain to make a splashing sound like a drunken fish. Miss Muxdröözol had frozen his brain immediately upon his death on Mount Nebo. Therefore, if there is an afterlife, he—or a brainless version of “he”—must have already experienced it by now. What would happen if his brain were revived? Would it register those new experiences?

You shake your head to change the direction of your thoughts. “Miss Muxdröözol, this collection is crazy. Have you lost your mind?”

Her body glimmers like mercury. “I am quite sane. My cryonicist friends believe that one day people can be revived if we freeze their brains today. What that means for the concept of an afterlife, I don’t know.”

She pauses. “Today I want to take a break from our usual discussions about God and omniscience and talk about a different kind of knowing. I want you to understand more about paradoxes of the brain, free will, time, consciousness, and causality. I’m going to drive you nuts, and by the time we’re done you’re going to question what it means to know something. These paradoxes will be biological and vast in their implications. We’ll return to pure philosophy, logic, and theology tomorrow.”2

Miss Muxdröözol sits on a wooden chair inlaid with a strange encryption:

![]()

“What’s that mean?” you ask.

“Never mind that. Let’s start with several quick experiments with the notion of causality—that cause is followed by effect. Put up your hands whenever you like.”

You pause and lift your hand.

“When we talked about omniscience, we also talked about knowing things like facts and events. I bet you think that you initiated the movement of your hand through your willpower.”

“Yes, of course. I willed it, and it happened.”

Miss Muxdröözol shakes her head. “You think that your psychological decision process is the trigger and prime cause of that movement. However, 0.8 seconds before you consciously decided to move your hands, there was an electrical signal in your brain called a readiness potential. Neuropsychologists have proven this. In other words, at the exact instant you consciously decided to move your hands, the actions had been already determined almost a second before. By monitoring your brain activity, I could have foreseen your movements before you made your conscious decisions. I could know before you know.”

You fiddle with some forceps lying on a low table. “Incredible,” you say. “You mean a neurologist could know that I was about to lift up these forceps before I made the conscious decision?”

Miss Muxdröözol nods. “Lesson 1: The relation between cause and effect, as you experience it, does not reflect the actual sequence of causal interdependence.” She pauses. “Here’s another experiment that should disrupt your notions of causality on a human scale. Come closer.”

You nod. For a second your eyes focus on the mounted head of a moose that is perched above the doors of Miss Muxdröözol’s museum of brains. At the left, you see a counter made of oak, soaked through with lacquers and oil. On it is a wooden statue of Dagon, one of the major Philistine gods of yore. The statue seems to be half man, half fish. Yes, Miss Muxdröözol has some odd tastes in decor.

She waves a gleaming electrode in front of you. “I’m going to insert this into your brain.”

“No way!” you say. “Get that out of my face.”

“The electrode is so thin, this won’t hurt a bit.” Without further hesitation, she inserts the wire into your brain.

She’s right. It doesn’t hurt.

Miss Muxdröözol looks at you. “What are you thinking? Let your mind drift.”

You look toward the bottles of brains and then at Miss Muxdröözol. She smiles as she strokes her silky, rainbow-colored hair. You let your thoughts drift. “I’m thinking of the biblical story of Noah’s ark. I am visualizing all the animals. I can see Noah and his sons Shem, Japeth, and Ham lifting huge pieces of wood to finish the construction. I smell animal dung. There is a rainbow in the sky.”

“Okay,” Miss Muxdröözol says. “This demonstrates another notion of causality and free will. I’ve been stimulating your brain with the electrode, and you experience this stimulation as spontaneously arising sensations rather than events I’ve imposed. Although I’m controlling you, you feel entirely free. Lesson 2: There are important illusions that reflect your brain’s interpretation of causality.”

This is all so unsettling. You walk away from her and into another room. Small American Indian rugs lay on the wooden floor, before a fireplace and windows. Against one wall is a large aquarium filled with red parrot fish about an inch in length. As they swim back and forth, they remind you of rubies, or perhaps the wisps and eddies of scarlet confetti.

Miss Muxdröözol follows you and brings out a huge buzzsaw. “Now I want to show you that the brain has its own time machine. Come closer.”

You look at the saw in her hand. “You’re not going to cut me with that!”

Miss Muxdröözol tosses saw to the floor. “Of course not. Just kidding.”

She extends her vestigial thumb and places its opal surface on your leg. “When I touch you, your brain needs half a second for computation of the sensory signals. However, you do not perceive the touch half a second later. You immediately experience having been touched. This means that your brain antedated the experience by half a second. Think of your brain as a post office that assigns a date to a letter earlier than the actual date of the letter.”

You look at your leg. “Miss Muxdröözol, you mean that my brain knows when the sensory signal arrived, and it compensates for its computation time? It creates the illusion of simultaneity?”

“Correct. Lesson 3: In order to perceive stimuli coming from the outside world in the correct order, we shift the perception backward in perceived time to the moment the stimulation actually took place. I call this the brain’s time machine.”

The smell of hamburgers and French fries wafts through the air. There must be a kitchen nearby. You look up and notice that on the window sill is a bronze bust of Albert Einstein. On the wall is a picture of Einstein boarding a large flying saucer.

“Miss Muxdröözol, you have some odd tastes. May I remove the electrode in my brain now?”

“Not yet. For our next experiment I want to measure your reaction time.” She hands you a golden ark engraved with two cherubim, or winged angels. Inside the box is a bell with a button on top.

She looks at you. “Press this button when you perceive my touch.”

She touches you, and you press the button. The bell rings.

“Sorry, Miss Muxdröözol. I pressed the button by accident.”

“You did not. Here’s what happened. Due to normal reaction time, you pushed the button 0.2 seconds after I touched you. However, 0.3 seconds later, I retroactively masked your conscious perception of the sensory stimulus by electrically stimulating your sensory cortex. Therefore, I canceled your perception in retrospect.”

“You mean I apologized for an imaginary error. I reacted properly to a stimulus that I did not perceive?”

“Lesson 4: An experience at this very moment may be canceled later. There’s trouble with determining simultaneity in the brain. Moreover, the notion of cause and effect becomes difficult. The temporal order of subjective events is a product of the brain’s interpretational processes, not a direct reflection of events making up those processes.”

The top of Miss Muxdröözol’s hair glistens in the fading rays of light, and even though her large face is in shadow, the extraordinary glint of her eyes is still apparent.

In one of Miss Muxdröözol’s hands is a Cosmopolitan magazine and a few UFO zines. Interesting combination. You sometimes find the idea of little gray men taking over the world almost comforting—perhaps they could solve some of the pollution and population problems.

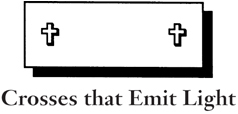

Miss Muxdröözol snaps her fingers. “Next experiment. Look at this card. What do you see?”

“Two crosses separated by about 4 degrees.”

“Okay, I’m going to light them in rapid succession. What did you see?”

“A single cross seems to move from one location to the other. It skated from left to right.”

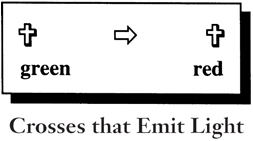

“What do you think will happen if I make one cross red and one cross green? What will happen to the color of the cross as it ‘moves’ from left to right?”

“Hmm. I think the illusion of motion will disappear, replaced by two separate flashing crosses. Or maybe the illusory ‘moving spot’ will gradually change from one color to the other as it moves.”

Miss Muxdröözol turns on the device. “Let’s give it a try.” A green cross-shaped light momentarily flashes on the left followed by a red light flashing on the right.

“Ooh,” you say.

“What do you see?”

“First the green light seems to be moving, and then it changes to red abruptly in the middle of its (illusory) passage from left to right.”

Miss Muxdröözol nods. “Okay, you saw it smoothly traveling but abruptly change color. At the halfway point between lights, it turned from green to red. Here’s my question. How were you able to fill in the spot at the times and positions between the two flashes of light, before the second flash occurred? How and why did the light turn red before the red light came on?”

You shake your head. “Did I have clairvoyance that let me know the color of the second flash before it was experienced?”

Miss Muxdröözol waves her hand in a modified Kung Fu outward block to dismiss your lame idea. “The answer is that the imaginary content—the color change—couldn’t have been created until after you saw the second colored light flash on.”

You take a deep breath. “But if I were able to consciously identify the second spot, wouldn’t it be too late to create the illusory color-switching and intermediate movement?”

Miss Muxdröözol opens a window to let in some fresh air. Outside you hear a few birds and the occasional croaking of frogs. “Researchers have proposed that the intervening motion is produced retrospectively, but only after the second flash occurs, and is projected backward in time.”

You brush back some hair that a faint breeze has caressed out of place. “I like these perception experiments,” you say. “Have any other experiments we can do?”

“Certainly. Let’s discuss one of my favorite temporal anomalies of consciousness. In the scientific literature, it’s called the ‘cutaneous rabbit.’ Follow me.”

Miss Muxdröözol leads you over to a velvet bench beside a painting of the Mona Lisa.

“Where did you get that?” you say.

“It’s a long story. I won it in the contest described in Chapter 5.”

“Chapter 5? You act as if we’re in some kind of book?”

She ignores your question. “May I attach electrodes to your arm?”

You consider the question for a moment. “Sure, I’ll do anything in the name of science.”

She places mechanical tappers on your wrist, elbow, and upper arm. “I will now deliver a series of quick rhythmical taps. Five taps on your wrist, two at your elbow, and three more on your upper arm.”

You look up from your arm. “It feels as if the taps travel in a regular sequence over equal-spaced locations on my arm—as if a little animal were smoothly hopping along the length of the arm from wrist to shoulder.”

She nods. “Exactly. That’s why it’s called the ‘cutaneous rabbit.’ Cutaneous means skin. Even though I made taps at only three places along your arm, you felt as if a rabbit were hopping continuously along the arm.”

“Miss Muxdröözol, how could my brain know that after five taps on the wrist there were going to be some taps on the elbow?”

“Neuropsychologists have determined that a person’s experience of the ‘departure’ of the taps from the wrist begins with the second set of taps at the elbow. However, if we didn’t deliver the elbow taps, you would experience all five taps at your wrist, as expected.”

“Miss Muxdröözol, let me get this straight. Obviously, the brain can’t know about a tap at the elbow until after it happens. Right?” You rub your elbow. “Maybe the brain delays the conscious experience until after all the taps have been ‘received,’ and then it revises the sensory data to fit a theory of motion and sends this time-altered version of reality to our consciousness.”

Miss Muxdröözol sits down beside you. She begins to play nervously with a few of her thoracic vertebrae. She says with rare uncertainty, “You said that you thought the brain delays the conscious experience until after all the taps have been received. But would the brain always delay response to one tap in case one more came? If not, how does the brain know when to delay? I don’t know the answers.”

Miss Muxdröözol pauses. “Want to try another experiment? It also deals with your mind playing tricks with time.”

“It sounds interesting, but each experiment is weirder than the last. They are fascinating though.”

Miss Muxdröözol walks over to you with an electrode in her hand. “Hold still. I’m now placing an electrode in your left cortex.”

You step back.

“It will be okay.” She places an electrode in the left hemisphere of your brain. You hear a slight crunching sound as she penetrates your skull, but the pain you feel is less than a mosquito’s bite. “I’m placing another electrode on your left hand. I’m stimulating your cortex before your left hand is stimulated. Did you feel the tingles in this order?”

“No. I know that the left side of the brain controls sensation on the right side of the body. I’d expect to feel two tingles: first on my right hand, induced by the brain stimulation, and then on my left hand. What I did feel was reversed. First I felt the left hand tingle, then the right.”

“You see that the timing of ‘mental’ and ‘physical’ events can be all messed up.” She pauses. “May I implant an electrode in your brain’s motor cortex?”

“I suppose so. You wouldn’t take no for an answer.”

“Good. Now, I have wired you to an old-fashioned tape cassette player. On the tape is the Mormon Tabernacle Choir singing the ‘Hallelujah Chorus.’ I want you to press a button on the cassette player to advance the music whenever you wish.”

You begin the experiment, and the tape changes songs, but—wait!—you are confused. “Miss Muxdröözol, the cassette player seems to change songs before I have even decided to make a change! It seems to anticipate my decision.”

“Quite right. But I tricked you. The player’s button is a dummy button, and did not have any affect on the cassette player. What actually advanced the songs was the amplified signal from the electrode in your motor cortex. Again, we see that voluntary motions are not initiated by our conscious minds! The signal occurred before your conscious intent to push the button. Scientists call this phenomenon the precognitive carousel because they tried this test using a carousel and slide projector. Subjects advanced slides just as they were about to push the button!”

Miss Muxdröözol removes the wire from your head, and then you sit down on a large spongelike piece of furniture. It smells like limes and occasionally purrs. Perhaps this kind of furniture is common for aliens of Miss Muxdröözol’s species.

She removes a package from her pocket. “Care for some seaweed?” She folds her multiply jointed leg and begins to eat a portion of seaweed that looks like it has been shredded beforehand. The shreds wind around one another like braids of hair. “We do not eat meat on our world. At least, not anymore.”

“No thanks,” you say.

She looks at you with her glistening eyes. “Let’s summarize. The mind plays tricks with time by making slight temporal adjustments. Today’s lessons show that the brain plays with the concept of simultaneity and projects events back in time. You’ve also learned about cutaneous rabbits and precognitive carousels—all terminology in the serious psychological literature.”

The two of you are silent for a while. Miss Muxdröözol tosses one of her vertebrae to you.

You hold the vertebra tightly in your hand. Perhaps this is a way that her species signals a desire for intimate friendship.

You look at Miss Muxdröözol. “Miss Muxdröözol, would you like to have some dinner together? I could get reservations for two at The Four Seasons. They have a vegetarian menu.”

Miss Muxdröözol pauses for a few seconds considering your question. She waves her forelimbs. “Thank you for the offer, but we usually don’t enjoy the food you Earthlings enjoy. Frankly, I prefer something more jumentous—”

Before she finishes, you take her hand and smile at her. “Perhaps while you are eating your seaweed, you wouldn’t mind me placing electrodes on your scalp. Won’t hurt a bit.” You start running after her as she bolts, making silly sounds that imitate the crunching of seaweed.

MUSINGS AND SPECULATIONS

The experiments in this chapter demonstrate how the mind plays tricks with time, and are all based on numerous different physiological experiments conducted by Wilder Penfield, Benjamin Libet, Paul Kolers, M. von Grünau, H. van der Waals, C. Roelofs, and others, and described by Daniel Dennett, Marcel Kinsbourne, and Rainer Wolf.3 Voluntary motions are not initiated by our conscious minds. And the brain does seem to have a “time machine” for antedating perceptions. The brain “projects” mental events backward in time in strange ways.

I discuss these and other paradoxes of the brain in my book Time: A Traveler’s Guide. Note that the various biological and mental paradoxes raise interesting issues about who is actually in control of our actions and seem to place organic limitations on our knowledge. The theological implications are broad. What if Eve’s intent to reach for the forbidden fruit was not initiated by her conscious mind? What if God’s intent to commit some act was not initiated by His conscious mind?

These topics touch on our discussions about how an omniscient God may be incompatible with free will. As many have noted, omniscience need not imply a denial of free will, because knowing—being conscious of—something does not cause something any more than knowing what the President had for breakfast invalidates the fact that he chose freely. But can one choose freely if one chooses before one is conscious of choosing? We’ll discuss these topics in more depth in chapters that follow.

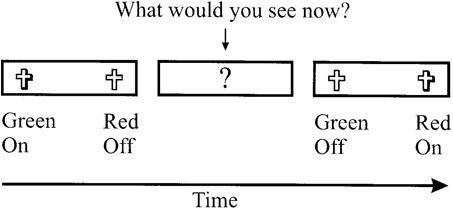

Figure 9.1 is a schematic illustration of the green light/red light experiment discussed in this chapter. Subjects actually report seeing the color of a “moving” cross switch midtrajectory from green to red. How are we able perceptually to fill in the empty spot between two crosses at the intervening places and times (along a path running from the first to the second flash) before that second flash occurs? One possible explanation is that the brain has an editing stage prior to consciousness. Perhaps there is a time delay, as is common in “live” TV or radio broadcasts, that allows the brain to package stimuli before they reach consciousness. In the brain’s editing room, missing frames are filled in after the red (second) light flashes, and the brain inserts these back in perceived time like a director splicing in new frames in a videotape. By the time the finished piece arrives at consciousness, it already has its illusory continuity.

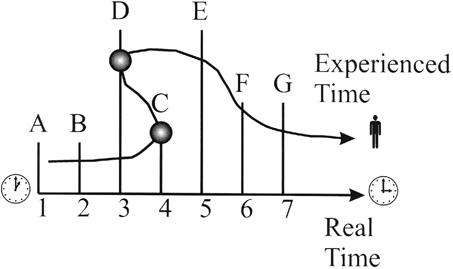

Figure 9.2 reinforces what you have learned in this chapter, namely that the time line experienced consciously by you is often quite different from the “objective” time line of events occurring in your brain or in real life. In short, the time lines do not correspond and can develop kinks and event-order differences relative to one another. Daniel Dennett and Marcel Kinsbourne believe that this nonalignment is “no more mysterious or contracausal than the realization that the individual scenes in movies are often shot out of sequence.” Nevertheless, disparities among time lines should stimulate fascinating adventures and experiments in consciousness and chronology, particularly as research in computer–brain interfaces matures in the twenty-first century.

Researchers have also conducted experiments relating to time and free will. For example, a subject with brain waves monitored is asked to flex his wrist whenever he feels like it. The subject watches a rapidly moving clock and reports the exact time of his subjective intention to flex his wrist. The electrode responds about 300 milliseconds before the decision is experienced. This means that you can know a person’s intent before the person does! This also certainly means that a God, even with very limited omniscience, can know a person’s intent before the person does. The sensation of free will, created in memory, occurs after the fact as a convenient way to record the decision. Some might argue that free will in the religious sense, involving big moral issues, takes place on a different time scale such that this model of the brain does not apply. However, if scientists can demonstrate that some decisions are determined in the brain before we are aware of them, perhaps many or all of our decisions are predetermined.

Other time experiments involve alternately flashing police car lights that can appear to move back and forth. Moreover, one light appears to move toward the other a split second before the other flashes. Obviously, the brain can’t predict the future and know the other light is going to flash before it does. The whole experience of movement is created after the fact. All experiences are created after the fact.

I suggest that readers interested in various temporal anomalies of consciousness read Dennett and Kinsbourne’s article, “Time and the Observer: The Where and When of Consciousness in the Brain.”4

Fig. 9.1.A green light and red light are placed close to one another. The green light is flashed, and then the red light is flashed. What do you perceive in the interval between the time the green and red lights are flashed?

Fig. 9.2.Time line kinks. A subjective sequence of experienced events (top line) often does not coincide with events in the brain in real time (bottom line).

God makes an interesting point: despite the hierarchical structure of human religion, there isn’t any middleman. There’s only Him.… Peeping out at all of His interior/exterior Escher-like universe-body simultaneously as if the skin of reality was the skin of the Creator’s optic nerve. Thus, His omniscience belies intimate contact with all of creation, implies a co-creator status to any sentient beings, especially nutty ones like humanity.

—Martin Olson, personal communication describing a fragment from his Encyclopedia of Hell