“God will provide for this kitten.”

“What makes you think so?”

“Because I know it! Not a sparrow falls to the ground without His seeing it.”

“But it falls, just the same. What good is seeing it fall?”

—Mark Twain, The Mysterious Stranger

Knowing what Thou knowest not is, in a sense, Omniscience.

—Piet Hein, Grooks

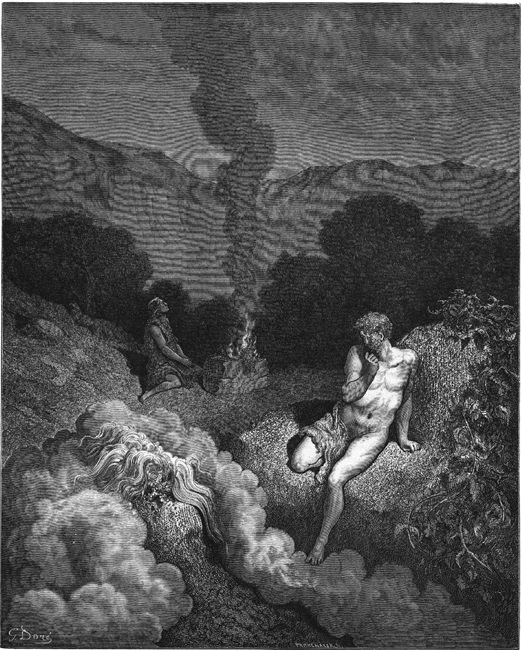

When I was ten years old, I recall leafing through a collection of biblical illustrations created by the famous French artist Gustave Doré, who lived from 1832 to 1883. I remember the beautiful creation scenes, the scary visions of Noah’s flood, the huge battles with Joshua committing the town of Ai to flames. Perhaps the scene that stuck in my mind most was the one of Moses coming down from Mount Sinai with the Ten Commandments (Figure I.1). The tablets were supposed to be the work of God.

Even at this early age, I knew that God was supposed to be omniscient, or all-knowing. I asked my father what this really meant. Did God know Eve would eat the apple? That Cain would kill Abel (Figure I.2)? Could God be surprised?

My father had no definitive answers.

Before proceeding further, it’s useful to have a working definition of God. This is certainly a difficult challenge! Throughout history, God has meant something different to different societies. In some sense, our concept of God has evolved, and so has our definition of atheism. Karen Armstrong in A History of God suggests that “had the notion of God not had this flexibility, it would not have survived to become one of the great human ideas.… Is the ‘God’ who is rejected by atheists today, the God of the patriarchs, the God of the prophets, the God of the philosophers, the God of the mystics or the God of the eighteenth-century deists?”1 Like a lump of heated silver changing from solid to liquid to gas, atheism has been the in-between state for religions. Jews, Christians, Muslims, and Baha’is were all called atheists by their predecessor religious forms.

Whatever you believe, clearly we humans often experience feelings and ideas that transcend our ordinary lives. Of course, these experiences are not always regarded as divine. Psychiatrists may relegate them to heightened activity of the brain’s temporal lobes. Buddhists see the experiences as natural to humans and do not invoke a deity. For now, let us use a very common Western definition of God. Of those people in the industrialized West who say they believe in God, studies show that most are monotheists. For these people, God is usually understood to be:

All powerful, all knowing, and all good; who created out of nothing the universe and everything in it with the exception of Himself; who is uncreated and eternal, a noncorporeal spirit who created, loves, and can grant eternal life to humans.2

The overwhelming majority of Americans who say they believe in God also believe God affects their lives. Numerous other definitions of God are given at the end of Chapter 15.

I should also note that God has historically been thought of as a male deity in religions such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Because I will frequently be alluding to the God of these monotheistic faiths, I use the conventional masculine terminology “He,” although I can certainly sympathize with feminists who may be uncomfortable with this traditional bias.

Fig. I.1. Moses coming down from Mount Sinai. Reprinted from Gustave Doré, The Doré Bible Illustrations (New York: Dover, 1974), 40.

Fig. I.2. Cain and Abel offering their sacrifices to God. Reprinted from Gustave Doré, The Doré Bible Illustrations (New York: Dover, 1974), 4.

In this book I don’t discuss some of the conventional, logical proofs of God’s existence. Instead, I discuss how we might understand the characteristics and limitations of omniscient beings. I also invite discussion about whether or not it is rational to believe in God’s existence. As Steven J. Brams points out in his book Superior Beings, “The rationality of theistic belief is separate from its truth—a belief need not be true or even verifiable to be rational.”3

What can we mere humans, with our limited three-pound mass of brain, truly understand about a being who may be timeless, higher-dimensional, and all-knowing? Followers of the Koran have often suggested that because God has no cause or temporal dimension, there is absolutely nothing we can say about Him. Our brains are not up to the task. The Jewish philosopher Bahya ibn Pakudah (d. 1080) believed that the only people who had a hope of understanding God were the prophets and philosophers. Everyone else was simply “worshiping a projection of himself.”4 Similarly, Muslim thinker Abu Hamidal-Ghazzali (1058–1111) thought that only special people, like mystics and prophets, could get a glimpse of God; nevertheless, most ordinary folk should not deny the existence of God—a blind man should not deny the rainbow’s existence simply because he cannot appreciate it.

Even with our working definition of God as all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-good, many modern thinkers say that this concept is insufficient. For example, anthropologist Donald Symons says the question of God’s existence, or perhaps any analytical discussion of God, is meaningless without a very rigorous definition of God. He writes:

Do you believe [fill in any three letters] exists? You have to know more about what’s in the brackets and how its existence or nonexistence might be determined, or at least, what kinds of evidence might potentially bear on the question. If you find out that the questioner has essentially no ideas about the characteristics of the [ ] (such as, for example, whether it is made of matter), and, more importantly, states that no conceivable observation could have any bearing on the existence/nonexistence question, then to me the original question is meaningless, or incoherent, or empty, or some similar concept.5

However, we don’t need to let Symons’s valid concerns restrain us from discussing these weighty matters. As I said, in this book I’ll focus on the question of omniscience. For those of you who do not believe in God, the discussions might be applied to hypothetical powerful beings. This book also includes numerous other intriguing religious concepts and paradoxes ranging from the dreaded “Devil’s Offer” to the “Paradox of Eden,” some of which cause people to question God’s justice and our own concept of fairness.

When we say a being is all-knowing, there are many kinds of knowledge the being could have.6 This makes discussions of omniscient beings a challenge. For example, knowledge may be factual or propositional: a superior being may know that the Peloponnesian War was fought by two leading city-states in ancient Greece, Athens and Sparta. Another category of knowledge is procedural, knowing how to accomplish a task such as playing chess, baking a cake, making love, performing a Kung Fu block, shooting an arrow, or creating primitive life in a test tube. For us at least, reading about shooting an arrow is not the same as actually being able to shoot an arrow. Procedural knowing implies actually being able to perform the act. (One might wonder what it actually means for a nonphysical God transcending time and space to have “knowledge” of sex and other physical acts.) Yet another kind of knowledge, experiential, comes from direct experience. This is the kind of knowledge referred to when someone says, “I know love” or “I know fear.”

There are, of course, some standard philosophical problems that arise with an omniscient God, such as the problem of free will. If God is all-knowing (including all-knowing of future events) and all-powerful, then how can humans be held responsible for making choices? Can an omniscient being know the delight of learning new knowledge? Some have suggested that God may reside outside of time and so sees past, present, and future in a blinding flash, but since we limited beings don’t know the future, we are, in some sense, “free.” If we have free will in such a way that the future is not preordained, does this mean God has limited omniscience? If God is limited, what are His limitations? Could it be that logic itself limits God so that an omnipotent God could not create a boulder so heavy that He could not lift it, or an omniscient God could not know what it is like to not know? Could God create a person whose actions He cannot know?

The questions pour like a waterfall from an infinite river. If there exists a God (or powerful alien being) who is omniscient, or all-knowing, what kind of relation could we have with such a being, what logical paradoxes arise that might cast doubt on His existence, and what effect would this being have on humankind? Although some philosophers of science would argue that the notion of a supernatural God, by definition, is untestable and therefore beyond the domain of science, there are certain principles of pure logic we may use to glimpse the infinite and dream daring dreams.

* * *

Perhaps, also by definition, an omniscient being cannot make a mistake. Michael Shermer in Why We Believe suggests that either God allowed Nazis to kill Jews, in which case He is not omnibenevolent or omniscient, or God was unable to prevent Nazis from killing Jews, in which case He is not omnipotent. Of course, there are numerous reasons why an omniscient God would not intervene. Other scholars argue that God can prevent misery but permits it because misery provides a necessary test in which greatness evolves, whether it be for life-forms (in the crucible of brutal competition by natural selection) or for entire nations (Israel would not have been created without Hitler’s atrocities and the ensuing reparations to the Jews). We’ll touch upon all these issues in this book.

I can give an unending list of examples of omniscient gods in religion. Humans seem to need and require an omniscient God. In Islam, for example, Allah has many names, including the Real Truth (al-Haqq), the Omnipotent (al-’Aziz), the Hearer (as-Sami’), and the Omniscient (al-’Alim). Bahaullah, the prophet of the Baha’i faith, frequently refers to God as “omniscient and all-perceiving.” Traditional Judaism and Christianity explain biological forms, with all their wonderfully complex environmental adaptations, as the obvious creation of an omniscient God. According to this logic, God foresaw the needs of creatures and gave them eyes, wings, prehensile tails for grasping, camouflage, and so forth. In Hinduism, God is nonmaterial, perfect, omniscient, and omnipotent. (Hindus do often worship local deities, but worshipers often think of the deities as manifestations of a single high God.) According to the ancient Tantric tradition, our ultimate state is omniscience, which provides understanding of all of the universe’s mysteries and forces. According to the Indian religion Jainism, a monk can attain omniscience through various meditative and physical practices, like yoga. When the person puts an end to all karmas, the person attains omniscience. In Zoroastrianism, a religion started in Persia (now Iran), the supreme creator god Ormazd (Ahura Mazda) is omniscient. Buddhists believe that Sakyamuni (563–483 B.C.), another name for the historical Buddha who founded Buddhism, was omniscient. Even the sphinx, the ancient mythological creature with a lion’s body and human head, was thought to be omniscient.7

Despite these overwhelming examples of belief in God’s omniscience, there are several notable exceptions of ancient writers limiting God’s omniscience. For example, the ninth-century Persian Jewish writer Hiwi al-Balkhi suggested that God was neither omnipotent nor omniscient because there were many injustices and inconsistencies in the Bible. Another example occurs in the various earth-diver myths of the ancient Slavs and Finno-Ugric peoples. In these tales, God is neither omniscient nor omnipotent, because He often relies on the Devil for knowledge. According to these myths, although God and the Devil created the world together, God and the Devil later became enemies. Many ancient Roman, Greek, and Scandinavian gods were clearly limited in their knowledge. Other religions, for example, those of certain North American Indians or Central and South Africans, suggest that while God is omniscient, He has withdrawn from the world and cannot be coaxed by prayer. Similar ideas of God’s self-imposed limitations are found in Jewish mysticism, such as Lurianic Kabbalah, which is discussed in more detail in “Some Final Thoughts” at the end of this book.

* * *

The science of omniscience need not remain confined to the dusty dens of old rabbis or the esoteric ramblings of philosopher-priests, beyond the range of our own exciting experiments and careful thoughts. I use the word “science” because it implies the logical, systematic testing of ideas and hypotheses. Many of the concepts, thought exercises, and experiments in this book are accessible to both students and lay people. The challenging task of imagining omniscient beings is useful for any species that dreams of understanding its place in a vast universe. Although this book is mostly about the science of omniscience, it does touch briefly on mysticism. Of course, the line between science and mysticism sometimes grows thin. Today, many philosophers and theologians would agree that paradoxes of omniscience, free will, faith, and belief are among the most profound and perplexing arenas of human thought.

When beginning this book, I did not set out to write a systematic and comprehensive study of omniscience and religious paradoxes. Instead, I chose topics that interested me personally and that I think will enlighten a wide range of readers. Although the concept of omniscience is centuries old, its strange consequences are still not widely known today. People often learn of them with a sense of awe, mystery, and bewilderment. Even armed with the experiments in this book, you’ll still have only a vague understanding of omniscience and religious paradoxes, which will no doubt plague you for a long time.

Why contemplate the properties of omniscient beings and their powers and limitations? Philosophers and theologians feel the excitement of the creative process when they leave the bounds of the known to venture far into unexplored territory lying beyond our ordinary experience. When we imagine the powers of superior beings, we are at the same time holding a mirror to ourselves, revealing our own prejudices and preconceived notions. The science of omniscience also appeals to young minds, and I know of no better way to stimulate students than to muse about the powers of omniscient beings. Creative minds love roaming freely through the spiritual implications of the simple logical experiments. Most of the challenging questions in this book cannot be answered to theologians’ satisfaction. Yet the mere asking of these questions stretches our minds, and the continual search for answers provides useful insights along the way.

This book will allow you to travel through time and space, and you needn’t be an expert in philosophy. Some information is repeated so that each chapter contains sufficient background information, but I suggest you read the chapters in order as you gradually build your knowledge. To facilitate your journey, I start some chapters with a dialogue between quirky explorers who experiment with omniscience. This simple science fiction is good fun, but it also serves a serious purpose, that of expanding your imagination.

Archaeological evidence indicates that even the Neanderthals 50,000 years ago stained their dead with red ocher, perhaps to prepare the departed for some kind of afterlife. Paleoanthropologists tell us that primitive humans worshiped gods at the dawn of human existence, as soon as their brain cases became large and the creatures left records for us in their artworks. The names and faces of the gods may have changed, but the drive has always been the same: Humans try to forge a connection to powerful, supernatural forces for comfort and survival in a dangerous world. Obviously, God has meant different things to different peoples through time, and every individual has a different experience or concept of God. Yet the pervasiveness of God is emphasized dramatically by Rene Dubos in A God Within:

Very soon in his social evolution, however, perhaps at the time of becoming Homo sapiens, [the human] began to search for a reality different in kind from that which he could see, touch, hear, smell, or otherwise apprehend directly. His awareness of the external world came to transcend his concrete experiences of the objects and creatures he dealt with—as if he perceived in them a form of existence deeper than that revealed by outward appearances. He imagined, though probably not consciously, a Thing behind or within the thing, a Force responsible for the visible movement. This immaterial Thing or Force he regarded as a god—calling it by whatever name used to denote the principle he thought to be hidden within external reality. Even in modern times, the people of tribes that have remained in a Stone Age culture imagine deities everywhere around them and tend to regard gods and goddesses as more real than concrete objects and creatures. The conceptual environment of primitive man commonly affects his life more profoundly than his external environment. And this is also true of modern man.8

Today, many people believe that the Bible is essentially the word of God. Others, like Marcus J. Borg, author of Reading the Bible Again for the First Time, believe that the Bible should be taken seriously but not literally. To Borg, the Bible is an imperfect lens through which we glimpse God—and we should not worship the lens but that which is beyond the lens.9 However, whatever you believe about the possibility of omniscience, or the limitations of a biblical God, the practical analogies in this book will raise questions about the way you see the world and will therefore shape the way you think about the universe and God. For example, you will become more conscious of what it means to be omniscient or have a “superior” mind. Contemplating omniscience is as startling and rewarding as seeing a dazzling supernova in outer space for the first time.

One of the reasons why religions seem irrelevant today is that many of us no longer have the sense that we are surrounded by the unseen.

—Karen Armstrong, A History of God

The function of religion is to confront the paradoxes and contradictions and ultimate mysteries of man and the cosmos; to make sense and reason of what lies beneath the irreducible irrationalities of man’s life; to pierce the surrounding darkness with pinpoints of light, or occasionally to rip away for a startling moment the cosmic shroud.

—Lewis Mumford, The Conduct of Life

If there is a gently sloping ability continuum from the amoeba to the aardvark, and from the aardvark to the anthropoid apes and us, why doesn’t such a continuum extend from us to God? Who lives in the cosmic chasm? Angels, Elohim, djinn, elementals, or even, perhaps, some of the demons? What is their nature? What sort of communication can we hope to have with them?

—Lionel and Patricia Fanthorpe, Mysteries of the Bible