THE MOST IMPORTANT ARCHAEOLOGICAL SITES FROM THE NORTH TO THE SOUTH OF ITALY

ROCK ART, ANTHROPOMORPHIC STELES, AND FROZEN MUMMIES

In the Alpine region, as in so many mountainous places, human experience and the use of land are shaped by seasonality. Alpine valleys provide good summer pastures, with flocks and herds climbing up the mountain in the warm season. In the winter season, the flocks are conducted down to more mild altitudes, where they find shelter during the cold months. It is in the Alpine environment that during the Copper Age some of the most outstanding rock art of Europe was carved and exceptional sacred areas were discovered. To the same period belongs the frozen mummy of a man who was killed at high altitude. The body remained hidden in the ice until 1991. These sites and discoveries are giving us a thorough picture of spiritual life between the fourth and the third millennium BC in northern Italy.

The rock art in the Alpine valleys of Valcamonica and Valtellina (Lombardy) was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1979. The petroglyphs carved on the rocks of these valleys constitute an archaeological, artistic, ethnographic, and historical patrimony of inestimable value, not only for its antiquity, but also for its thematic and iconographic wealth. There are some three hundred thousand engraved figures belonging to different periods in the area.

Figure 4.1. Petroglyphs from Valcamonica with a Camunian rose and an anthropomorphic figure. Di Luca Giarelli–Opera propria, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8644541

The first systematic definition of the Valcamonica chronology was proposed back in the 1960s and 1970s.1 This study enlarged the period of engraving activity and postulated the existence of different phases or layers over the engraved rocks. Styles I and II were placed during the Neolithic, style III during the Copper Age and Bronze Age, while style IV was in use from the end of the Bronze Age to the end of the Iron Age. Subsequent phases belong to historical times. During the Roman period, the site was abandoned, but with the arrival of Christianity, artists came back to the rocky areas to engrave Christian symbols.

The chronology of Valcamonica rock art is strictly tied to archaeological evidence, mainly thanks to the abundant weapon figures that date from the Copper Age to the Iron Age and that can be stylistically compared to actual artifacts whose date is known. The first engravings date to the Paleolithic, representing large animals in sub-naturalistic style. Between the end of the Neolithic and the Copper Age depictions of humans can be found together with symbolic engravings linked to the appearance of the wheel, the carriage, and the first metalworking techniques. In the Neolithic and until the early Copper Age the most typical engravings represent ancient topographical compositions. Figurative and abstract art coexist in the Camunian Rock art.

In the Copper Age, that rock art flourished. The so-called Remedello dagger, a copper dagger with a triangular blade, is the most frequently represented weapon. This particular type of dagger was recovered in the burials of the Remedello necropolis, a site about 100 kilometers south of Valcamonica, and dates to between 2900–2800 and 2500–2400 BC. The first burials of Remedello were recovered in 1884, followed by the excavation directed by Gaetano Chierici, and then by Giovanni Bandieri. Chierici is among the most distinguished Italian naturalists and archaeologists of the time. In the rock engravings of Valcamonica these daggers appear grouped, ordered in one direction or in the opposite one. Daggers with a triangular blade of the Remedello type were also made of flint and bone; it was an emblematic object connected to elites and warrior ideology. Outside Valtellina and Valcamonica areas, this dagger is visible on statue-steles and anthropomorphic steles, usually in a position close to the belt. A stele is a stone slab, generally taller than it is wide, erected as a monument.

Together with engravings, a large number of statue-steles (about fifty) depicting human figures were recovered on the site and in its immediate vicinity. These depicted anthropomorphic figures, the Remedello-type daggers, the sun, double spirals, and other designs including wild and domestic animals and a plow pulled by oxen.

Archaeological excavations have confirmed the presence of such steles around prehistoric places of worship in various locations in the valley. Steles are a pan-European phenomenon in the fourth and the third millennium BC Europe and are associated with the emerging social transformations characterizing Europe in the Copper Age. While the varying stylistic traditions of the steles differ considerably across Europe, they also share a set of general aesthetic choices for representing the human body, reducing the body to a rigidly schematic, highly stylized form with a widely shared geometry and with emphasis on its surface as a canvas for social markings, particularly of gender. The so-called statue-steles of Valcamonica can, however, be defined as quite unusual in the European style. They follow an aesthetic canon that shares many features with the local rock art tradition, making them unique.

The appearance of these extraordinary compositions consisting of symbols, weapons, animals, and anthropomorphic images coincides with the growth of metallurgy and connected technologies, which included new strategies for obtaining raw materials and controlling the territory in which they were located.

The Megalithic Area of Saint-Martin-de-Corléans is another absolutely outstanding Copper Age site in which highly symbolic prehistoric art is present. The site was uncovered in 1969 in the western outskirts of the city of Aosta (Val d’Aosta) on the alluvial terrace of the Dora Baltea River, and extends over an area of one hectare. The stratified deposits testify to a long occupation of the area, from the end of the Neolithic period to the Iron Age and Roman epoch, but the most significant archaeological features are undoubtedly the megalithic monuments, the steles, and the tombs dating to the Copper Age and the beginning of the Early Bronze Age.

Figure 4.2. Traces of the ritual plowing in Saint-Martin-de-Corléans Megalithic Area Museum. Di PLunardi–Opera propria, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=51450082

The site remained active as an area of worship and burial for almost a millennium, from about 3000 BC to 1900 BC. Its history can be divided into five chronological stages on the basis of archaeological research.

An alignment of twenty-two large cylindrical wooden poles orientated from northeast to southwest represent the earliest occupation phase in the Neolithic. During the second phase, dating to between 2750 and 2400 BC, the ritual area is enlarged with the construction of two orthogonal alignments of more than forty-five anthropomorphic steles placed along two orthogonal axes. These axes have a northeast-southwest and northwest-southeast orientation respectively, and maintain the alignment of the wooden poles belonging to the previous phase. Interestingly, ancient traces of plowing with the same alignment were also recovered. This alignment was not chosen at random. Instead, it is aligned along the path of the sun, allowing the rays of light to play upon the monuments for many hours each day; it is a solar axis. Everything built on the site was placed in relation to this axis, and because of it, every monument, burial, and stele enjoyed a direct relationship to the sun.2

The steles of Saint-Martin-de-Corléans are about two to three meters high and one meter wide, with thicknesses of a few tens of centimeters. They were made by using different types of stones characterized by different workability in terms of surface finishing processes. The steles were carved in two different artistic styles, which suggest also a different chronology. The so-called ancient style has the representations of clothing and anthropomorphic attributes reduced to essentials, while the so-called evolved style shows complex and detailed representations. The steles have common features in terms of style and iconography to the ones that were recovered at the Petit Chasseur near Sion (Switzerland). In the third phase, platforms associated with the steles were built on the site by using shale, a soft finely stratified sedimentary rock that formed from consolidated mud or clay, and river pebbles. These were interpreted as structures connected to ancient rituals because inside a group of cylindrical wells grains of wheat and millstones have been recovered. They have been interpreted as the material results of rituals connected to agriculture. Around 2300 BC, the site started to be used as a burial area. In this period, large tomb structures defined as megalithic were constructed. During this fourth phase, five tombs of various types were erected in different zones of the site, and the anthropomorphic steles belonging to the older phase of the site were systematically reused to construct these tombs. The systematic reuse of the steles was a common practice also in the following fifth phase (2100–1800 BC), during which a further three megalithic tombs were built.

These steles have been studied in detail from an archaeological and archaeometric point of view. A detailed characterization of the mineropetrographic rock types used in the production of the prehistoric steles allowed, in most cases, for the identification of the provenance area of the stone material. Combining archaeometric and archaeological data, it was observed that the steles belonging to the “ancient style” (type A) were of stone material from areas located near the archaeological site, while the steles belonging to the “evolved style” (type B) were made from more distant rock outcroppings—the Morgex marbles—about thirty kilometers from the site to further northeast up to Sion, in Switzerland, where similar stones were used for anthropomorphic steles at the megalithic site of le Petit Chasseur. This would confirm the existence of tight cultural connections across the Grand St. Bernard Pass connecting Italy to Switzerland since the Early Copper Age.

The megalithic design and architecture is distinctive to this region of the western Alps, yet the type A steles with engraved Remedello daggers and double spirals show that the community is already connected to the process of transformation that affected all of Europe from 2900 BC to the beginning of the Bronze Age. An ideological change takes place around 2500 BC also at Saint-Martin-de-Corléans, when type B steles are erected. This coincides with the earliest Bell Beaker presence in central Europe, and indeed at both Sion and Aosta we see the impact of Beaker ideology as symbols of artifacts and clothing are recorded on the stele of Saint-Martin-de-Corléans and le Petit Chasseur. The Bell Beaker steles have male and female genders, and expressions of rank and status shown in their extremely detailed carved costumes and ornaments. The elaborate dress code is something completely new and has no previous sources in Sion or Aosta. In this epoch, textile manufacturing is open to innovation and rapid change within a domestic mode of production. New textiles carry a potent symbolism in their patterns and colors. They are clearly a labor-intensive product and consequently become valuable. Equally important is the ability to use textiles to decorate the human body and enhance the status of the person wearing them. In this way, the human body itself becomes part of the symbolism of rank and status, and the textiles are the means of making the transformation visible. This explains why the patterns of Bell Beaker pottery are so similar to textile designs. At the beginning of the Early Bronze Age Saint-Martin-de-Corléans entered a phase of decline and was nearly abandoned. Some levels dated to Iron Age and Roman Age were found, indicating that the site was frequented also in these periods, despite having lost its religious and sacred function.

Further insights into the Copper Age come from the discovery of the ice mummy, or Similaun Man, mentioned above. The naturally mummified corpse of a man from the late Neolithic was found at 3,200 meters altitude near the Hauslabjoch mountain in the Ötztal Alps, and so has come to be known as Ötzi. The body lay in a rock hollow so that when the glacier froze, it went over it instead of crushing it. Thus, Ötzi and the things he had with him were extraordinarily well preserved, allowing unique insights into late Neolithic–early Copper Age.

Ötzi was discovered on September 19, 1991, by two mountain hikers on a ridge that forms the border between Austria (to the north) and Italy (to the south). As the hikers were approaching the rocky ridge, they saw the upper part of a body sticking out from a shallow, ice-filled depression. The unusual climatic conditions of 1991—including dust blown from the Sahara, resulting in enhanced melting of snow—had partly freed this body from its icy resting place, leading to the discovery.3 In the first few days after the discovery, several people visited the finding place, but nobody suspected that the body could be from prehistoric times. Rather, everybody was convinced that the body might belong to a mountain hiker who perished on the glacier some time ago.

Figure 4.3. The moment of the discovery and recovery of Ötzi the Iceman, in 1991. Di Vienna Report Agency/Sygma/Corbis–http://ilfattostorico.com/2011/06/26/lultima-cena-di-oetzi/, Pubblico dominio, https://it.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4017159

Four days after the discovery, the body was freed from the ice and brought to the Institute for Forensic Medicine at the University of Innsbruck (Switzerland), where Konrad Spindler from the Institute for Pre- and Protohistory at the University of Innsbruck recognized the equipment found together with the body as prehistoric.4 One of the more serious events was the determination of the exact location of the finding place, as it was very close to the Austrian-Italian border. After an official re-measuring of the borderline it was established that the Iceman had been found in Italy. According to international regulations, the Ötzi the Iceman therefore belonged to Italy.

Ötzi is estimated to have lived to his mid-forties, around fifty-three hundred years ago (around 3300 BC), which makes him the oldest natural mummy in Europe. He was found to have carried with him arrowheads and a knife made of flintstone as well as a copper axe. Interestingly, the stone and the metal come from the south and the north of the Alps, respectively, indicating long-distance trading of goods at that time.

His clothing included a cloak of woven grass over a striped leather jacket, a bearskin cap, and goatskin leggings. His shoes were made from bear and deer leather and filled with grass for insulation. Parts from more than a dozen different plants were used in his equipment. Radiological examinations showed the signs of enthesopathy in the knees, indicating that he spent many hours wandering in the mountains. The contents of his stomach have been analyzed and revealed that he had eaten a primitive type of cultivated wheat, possibly baked into bread, and game meat as well as dried sloes. Analyses revealed that he was infested with worms, and his fingernails revealed repeated bouts of disease. His body was covered in tattoos, some of which are on joints affected by arthritis, suggesting they may have served medical purposes.

Initially it was thought that he was a hunter or a shepherd who had been caught by bad weather. Later, his hair was found to contain toxic levels of arsenic that he might have absorbed during copper smelting. About ten years after his discovery, after high-end analyses and X-rays, an arrowhead was found stuck under his left shoulder blade. This arrowhead had pierced the subclavial artery, causing fatal blood loss. In addition, he had suffered a severe blow to the head. His gear contained traces of blood from at least four different people, including traces of two different people on one of his arrowheads—people he must have killed or severely wounded.

Following more than six years at the University of Innsbruck, where most of the scientific work was organized, in January 1998, Ötzi was brought to a newly established Archaeological Museum in Bolzano, Italy, where he is on display for the public, safely stored in a glass vitrine with controlled temperature and humidity at glacier-like conditions.

THE CITIES OF THE LIVING AND THE CITIES OF THE DEAD

Back in the 1950s on the basis of a survey conducted in the territory of the Etruscan city of Veii, the British archaeologist John Ward Perkins interpreted the various Early Iron Age deposits found on the plateau where the ancient city stood as the remains of small separated hamlets belonging to independent communities. All the proto-urban centers of Etruria were established on large tuff plateaus measuring between 150 and a little less than 200 hectares. Cemeteries belonging to different phases of the Iron Age and of the following Orientalizing periods were placed around these plateaus. Ward Perkins thought that those sparse settlements came together as an incipient urban community only after the Early Iron Age ended, thus during the Orientalizing and Archaic Ages, triggered by foreign influences, such as the new city-state model introduced to southern Italy by the recently founded Greek colonies.5 This interpretation was challenged in the following years mainly by Italian archaeologists, among them Renato Peroni, who argued that this process not only occurred earlier than the Orientalizing and Archaic Ages, but also that it was a fully local development. The proto-urban centers of Etruria would have developed into cities thanks to internal developments of the Iron Age societies, which were already started in the Late Bronze Age. The long-standing debate between the so-called exogenous and endogenous perspectives on the birth of the city is still ongoing, and is one of the many unresolved issues regarding the supposed priority of urbanization in Etruria as compared with nearby regions, such as Latium Vetus, where Rome is.6

Despite the origin and development of the city in the central Mediterranean being a crucial issue in European archaeology, most of the Etruscan cities are still insufficiently explored, although significant urban surveys and excavations have been undertaken in the cities of Vulci, Cerveteri, Tarquinia, and Veii.

Veii was the largest proto-urban site, measuring approximately 190 hectares, and it was located only seventeen kilometers north of Rome. The Final Bronze Age occupation is difficult to establish compared with other Etruscan cities, but some data on this period come from the Northwest Gate area and from the nearby village of Isola Farnese.

Recent excavation and surveys at Tarquinia have shown that some parts of the extensive plateau have been occupied since the Final Bronze Age and that the occupied area expanded from 2 hectares to 120 hectares between the Final Bronze Age and the Villanovan period (Iron Age). The central part of the city is famous for the Ara della Regina temple, the latest of a succession of temple structures. The impressive limestone walls and gates of the city have been standing since at least the fifth century BC.

Present-day Cerveteri was known in antiquity by the name of Caere, and it can be considered the key site of South Etruria. It is located six kilometers from the Tyrrhenian Sea and connected to the ports of Pyrgi, Alsium, and Punicum. The origin of this city also dates back to the Bronze Age and Iron Age. There is some dispute over the size of the Etruscan city, but 130 to 150 hectares appears to be a reasonable estimate made on the basis of the size of the large tuff plateau on which the city rests. The city was one of the principal centers of early bucchero production. This iconic Etruscan ceramic ware is distinguished by its black fabric as well as glossy, black surface achieved through the unique “reduction” method in which it was fired. The absence of oxygen in the firing chamber of the kilns was achieved by closing the vent holes, thus reducing the quantity of oxygen and creating a smoky atmosphere.

Nevertheless, the majority of our knowledge about Etruscan art, culture, beliefs, and lifestyle comes largely from their burials. The main necropolis near Cerveteri is known as Banditaccia, and flourished from the seventh century BC. It contains thousands of tombs organized in a city-like plan, with streets, small squares, and neighborhoods. The site contains very different types of tombs, comprising trenches cut in rock as well as tumuli. These were built with tuff blocks or carved in rock in the shape of huts or houses with an amazing number of architectonic details. The Banditaccia cemetery exemplifies the development of Etruscan funerary architecture, showing a complex tomb evolution.

By the late seventh century BC, large burial mounds were constructed in the Banditaccia cemetery that were as much as fifty meters in diameter and fifteen meters in height. These mounds have the appearance of round huts where earthen roofs sit on drums of tuff or walls surmounted by a circular cornice, approached by one access route across an encircling ditch. A corridor of between ten and fifteen meters in length reached the burial zone, and this same linearity was continued into the chambers beyond, through a sequence of small spaces.

Typical tombs of this period include the Regolini-Galassi tomb (from the name of the excavators) and the Tomba della Capanna (tomb of the hut). Slightly more recent are the Tomba dei Capitelli (tomb of the capitals) and the Tomba degli Scudi e Sedie (the tomb of the shields and chairs). Both of these two last tombs show distinctive domestic features, as the names suggest.

The Regolini-Galassi tomb was discovered still intact in 1836 and constitutes one of the main sources of evidence of the Orientalizing period in Etruria. It is one of the richest Etruscan family tombs in Caere. Its spaces are in part dug out of the tuff rock, and in part built using square blocks. A huge mound of earth, with a diameter of forty-eight meters, was used to cover the entire structure, giving it a monumental aspect also from the exterior. A dromos (corridor) provides access to the lower chamber intended for the main burial. A low wall with a window open for ritual purposes separates the corridor from the burial chamber. The tomb was built for two people, a woman and a man. The most prominent burial is the one belonging to a royal woman who was buried in the lower chamber with a rich funerary treasure made of personal belongings and refined golden jewelry. The most famous items are the great golden fibula, which is adorned with five tiny lions depicted striding across its surface, and the gold pectoral.

Figure 4.4. Great golden fibula from Regolini-Galassi tomb in Cerveteri now kept at the Etruscan Museum in Villa Giulia. By Sailko–Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30520908

A cremated man was placed in one of the two cells directly excavated in the tuff at both sides of the dromos. In the antechamber there is a bronze funerary bed, and sumptuous furnishings for ritual use, which refer to the aristocratic practice of the banquet. Here, a series of shields were positioned along the walls, and there were also three carts: a chariot, a cart for seated passengers, and one heavy cart used to transport the coffin. The most ancient tomb was subsequently incorporated into a more imposing mound with a larger diameter, including another five tombs, which continued to be used for at least another two centuries, until the first half of the fifth century BC.

At the end of the sixth century, extending into the fifth century BC, these distinctive tombs were replaced by smaller, street-lined square tombs, bound together by a common cornice, accompanied by external grave markers.

A number of monumental chamber tombs of the Colle dei Monterozzi necropolis at Tarquinia related in plan to the Regolini-Galassi tomb of Cerveteri. Among the most significant ones there is the Tomb of Bocchoris, so called after an Egyptianizing faience situla decorated in relief, including a hieroglyphic cartouche with the name of the pharaoh Bokenranf (Bokchoris in Greek). From the sixth century BC, the famous tomb paintings began to appear and remained in widespread use for the first half of fifth century BC.7

IN THE SHADOWS OF THE TEMPLES

Magna Graecia (Great Greece) was the name given by the Romans to the coastal areas of southern Italy in the present-day regions of Campania, Apulia, Basilicata, Calabria, and Sicily. Greek settlers arrived in Italy in the eighth century BC, bringing with them their Hellenic civilization, which left a long-lasting imprint on these regions. Two of the most important cities of Magna Graecia are Paestum and Agrigento.

The Greco-Roman city of Paestum is located in Campania, close to the city of Salerno. The first occupation of the area dates back to the Paleolithic, and traces of a Neolithic settlement have been found in the Temple of Ceres and in the Golden Gate areas. During the Copper Age, between the end of the fourth and the middle of the third millennium BC, the area was inhabited by communities belonging to the so-called Gaudo culture.

The Greek geographer Strabo informs us that the city of Poseidonia—this was the Greek name of Paestum—was established in the seventh century BC as a sub-colony of Sybaris, a city located on the Ionian Sea. This dating seems to be confirmed also by the archaeological data collected so far. The choice of this place for the city foundation was made because of its proximity to the mouth of the Sele River, which was an inland waterway and point of passage for trade. In fact, at the mouth of the river, the famous sanctuary of Hera was founded, having also the function of an emporium.

Figure 4.5. Paestum, aerial view of the temples from aerostatic balloon. Di V alfano–Opera propria, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=21788866

Between the sixth and the first half of the fifth century BC the city experienced its heyday. In this period the Etruscans’ neighbors were defeated and withdrew from the right bank of the Sele River to the north. The motherland Sybaris was destroyed in 510 BC by Crotone, leaving the colony alone. Possibly the citizens of Sybaris who escaped the destruction of the city found a way out by reaching Poseidonia, which became the richest and most important city of the area. The city was so wealthy that the so-called Basilica, the so-called Temple of Ceres, and the so-called Temple of Neptune were built just fifty years apart from each other.8

At the end of the fifth century BC the city came under the dominion of the Lucanians, an Italic population of Oscan origin who lived in the area. This passage, in all probability, was not due to a military conquest, but to a progressive assimilation of the Italic indigenous population, first as workers and then, gradually, in the political management of the city itself.

The city, which changed its name to Paistom at the very end of the fifth century BC, progressively lost its Greek character. However, it did not undergo a proper decline in the Lucan period. The richness and fertility of the Sele River plain allowed it to maintain a considerably wealthy lifestyle, which was comparable to the previous Greek period.

Cultural and social life also flourished, although Greek sources report the complaints of Greek citizens who felt that they had lost their original freedom.

A menace to the freedom of the city came instead from Macedonia, where Alexander the Molossus, uncle of Alexander the Great and king of Epirus, pursued the dream of conquering southern Italy. He freed several cities from the Lucanian yoke, including Paistom, but his death in battle in 331 BC stopped the project, and the city returned to Lucanian control.

Sixty years later, in 273 BC, Paistom came under Roman control, becoming a colony under Latin law and thus changing its name to Paestum. Paestum was always a faithful ally of Rome. During the Punic wars, after the defeat of Cannae, the city provided supplies of precious wheat to the Romans thronged inside Taranto to resist Hannibal.

Thanks to this relationship of trust with the center of power, to Paestum was granted the possibility of minting coins, a permission that remained valid until the Tiberian Age.

The city definitively entered an irreversible crisis in Late Antiquity, when the floods of the Salso River caused the gradual swamping of the city and the shrinkage of the settlement at its smallest point, which was concentrated in the area of the so-called Temple of Ceres. There a Christian basilica was built, and then the church of the Santa Maria del Granato was established. The church’s name derives from Punica granatum, the Latin name for pomegranate, a fruit that was a pagan symbol of fertility linked to the goddess Hera. Thus, the name was transmitted in a clear case of syncretism to protect the Christian city.

Today visitors to Paestum find its mighty walls of the Hellenistic-Lucan era still standing: the surrounding landscape of cultivated fields and low houses, with the small village that escaped from destruction and abandonment, can give an idea of what the foreign scholars from central and northern Europe saw as they traveled throughout Italy for the Grand Tour during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The Doric temples of Paestum dedicated to Hera and Athena are considered unique examples of Greek architecture in Italy and in the Mediterranean.

During the Second World War, the archaeological area of Paestum was transformed into a battle scenario and a landing spot for the Allied Powers,9 remaining under military control afterward. This circumstance is linked to one of the most important discoveries for the prehistory of southern Italy. In the autumn of 1943, during the construction of a landing strip operated by the aircraft of the Allied armed forces, a hill in the area called Spina-Gaudo was completely demolished. In the exposed section appeared what would later be identified as graves of a prehistoric culture until then unknown. Fortunately, among the British Royal Engineers corps was the “BP Mobile Archaeological Unit,”10 an unofficial group that was involved in making emergency excavations in the war territories when archaeological remains were identified. The leader and founder of the group was Lieutenant John George Samuel Brinson, an archaeology enthusiast, who upon his return to Essex founded a volunteer group called the Roman Essex Society, which carried out many excavations in Britain.

Lieutenant Brinson managed to stratigraphically dig tomb number 10 and tried to document number 9 as far as possible. Excavation of the cemetery was finished in the first years after the end of the war. It turned out to be composed of thirty-four tombs dating to the Copper Age. This prehistoric culture was named Gaudo after the place of its discovery.

Subsequently, numerous other traces of this culture have been found in a larger territory spanning from Apulia up to Rome, where recent emergency excavations in the southeastern outskirts have allowed digging the first stable settlement connected to this culture. Until this discovery, the Gaudo culture was considered a nomadic society, as it was known only from its burials. The artifacts excavated during and after the Second World War are displayed today in the Archaeological Museum of Paestum, which stands in the archaeological site area and presents a rich collection of artifacts from excavations within the ancient city. These objects include the sculptural decoration of the temples and some splendid funerary artworks from the ancient cemeteries that were also established in the area. The most famous of these burials is the so-called Tomb of the Diver, dating to between 480 and 470 BC.

The Tomb of the Diver is a funerary artifact made of travertine slabs. It is of significant historical and artistic value, as it is the only evidence of figurative and non-vascular Greek painting. The walls of the building and the covering slab itself are entirely plastered and decorated with a wall painting of a figurative subject, created using the fresco technique. The scenes depicted on the side slabs do not present interpretative problems, as almost all of them depict a symposium. The interpretation of the cover plate, the one with the iconic image of the diver, is instead controversial. At present, most scholars agree in attributing to this image a nonliteral but symbolic meaning. The dive would be a symbol of the passage from death to the afterlife.

Sicily also stands out in Magna Graecia for the richness of the cities founded by Greek settlers. One of the best preserved is Agrigento, the old Akragas, which was founded by settlers from Gela in 581 BC near the mouth of the river of the same name. With this move, the Geloi—as the inhabitants of Gela were called—hoped to contain the eastward expansion of their rival, the city of Selinunte.

Akragas was dominated from its beginning by tyrants; the first and the most famous of them was Phalaris.

Structures belonging to the archaic period are scanty and limited to few burials and some minor sanctuaries, while the existence of the city walls has not been archaeologically proven yet.

In the fifth century BC the city reached its peak with the construction of the most important temple complexes. This period of wealth was partly due to the defeat of Carthaginians in the battle of Himera, which allowed Akragas and Syracuse to dominate west and east Sicily respectively, a dominion that remained unchallenged for a long time. In this period the city was the home of some of the most famous Greek poets, such as Pindar and Simonides.

At the end of the fifth century BC, however, a new war with Carthage led to the definitive conquest of Akragas by the Carthaginians, who held it until 339 BC when it became part of the territory dominated by Syracuse.

Figure 4.6. Agrigento, the Kolymbetra garden. Di fab.–agrigento_kolymbetra, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27366456

In 262 BC during the first Punic war, Akragas was conquered by the Romans and changed its name to Agrigentum. It prospered throughout the Republican and Imperial periods, as shown by the splendid domus discovered in the area. These were restored in the fourth century AD together with some public buildings of the city.

In the ninth century AD the city was occupied by the Arabs and named Kerkent, and from the eleventh century was named Girgenti by the Normans. This name was held by the city until 1853, when the current denomination Agrigento was adopted.

The remains of the ancient Agrigento are located south of the modern one, grouped on the three hills that form the world-famous Valley of the Temples, the largest archaeological site in the world, extending for 1,300 hectares and inscribed on the World Heritage List since 1997. During the Middle Ages the settlement was located outside the ancient city, a circumstance that allowed for the outstanding preservation of the ancient structures, which are almost intact.

Together with part of structures belonging to the Greek and Roman city, in the archaeological park there are the remains of twelve temples in Doric style, a recently excavated Greek theater, and the Kolymbetra garden, site of the enormous artificial pool constructed by the tyrant Theron after the victory of Akragas over Himera in 480 BC.

The archaeological park of Agrigento is visited every year by more than one million tourists from all over the world, and is one of the most forward-thinking archaeological parks in Italy—the only one to date that has a sustainability report. This is a document that analyzes the impact of the site on the surrounding environment, in terms of economic, social, and cultural development. The decades-long battle against illegal construction in the park has led, finally, to an administration of the site that seemed impossible until just few years ago. Since 2015, most of the illegal structures built in the park have been demolished, and excavation and research activities have been resumed. Among the most outstanding discoveries, there is the above-mentioned Greek theater. From 2016 to the present a further three thousand square meters of the ancient city have been excavated and made accessible to the public. Further excavations are also planned. The relaunch of the archaeological site also has had a positive influence on the revival of the historical center of the modern city, which is one of the cities in Sicily most affected by illegal building.

Agrigento, its archaeological park, and its relationship with UNESCO represent an excellent example of how the redemption of an area devastated by the presence of the mafia and its illegal activities can come from its cultural and archaeological heritage.

ROME, THE ETERNAL CITY

Rome is considered the city that has the largest number of monuments in the world. The “eternal city” was inscribed in the World Heritage List in 1980, and according to UNESCO it has something like twenty-five thousand points of interest. The World Heritage site includes some of the major monuments of antiquity such as the Forums, the Mausoleum of Augustus, the Mausoleum of Hadrian, the Pantheon, Trajan’s Column, and the Column of Marcus Aurelius, as well as the religious and public buildings of papal Rome.

As happens in historical cities that have been inhabited over a long period of time, in Rome a good part of the ancient and medieval buildings were incorporated into later structures, creating a unique urban stratigraphy and landscape that allow one to literally walk into the past by simply strolling through the city center. The difficulty in distinguishing the ancient from the modern in many buildings in the city center may cause a sense of loss in first-time visitors to Rome. One of the well-known examples of the reuse of a preceding structure and its incorporation into a new building is the Basilica of Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri (St. Mary of the Angels and the Martyrs). Designed by Michelangelo in the sixteenth century, the church was built inside the ruined frigidarium of the Roman Baths of Diocletian in the Piazza della Repubblica.

In some cases, ancient buildings still substantially retain their original appearance despite numerous additions and modifications. The best example is perhaps the Pantheon, which was built by Marcus Agrippa during the reign of Augustus and then restored by Hadrian in the second century AD, taking on its present appearance. The building is cylindrical with a portico of large granite Corinthian columns under a pediment. A rectangular vestibule links the portico to the rotunda, which is under a coffered concrete dome, with a central opening to the sky called an oculus. Almost two thousand years after it was built, the Pantheon’s dome is still the world’s largest unreinforced concrete dome. The height to the oculus and the diameter of the interior circle are the same, forty-three meters. In the seventh century AD the Pantheon was used as a church dedicated to St. Mary and the Martyrs (Santa Maria ad Martyres, informally known as “Santa Maria Rotonda”), and several structures were added and then removed without modifying much its original architecture.

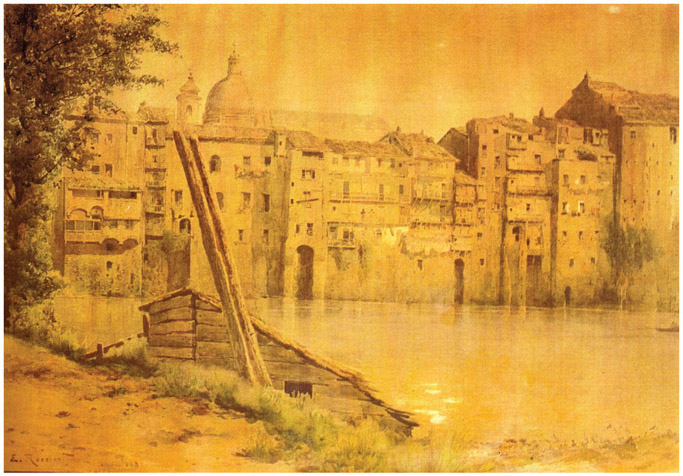

The charm of Rome lies indeed in the strong presence of the past, and this element has always attracted travelers and artists, both foreign and local. One of these is Ettore Roesler Franz, one of the most prolific

Figure 4.7. The Pantheon vault viewed from the center of the building. Di Architas–Opera propria, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=70188093

Figure 4.8. An image of Via della Fiumara, in Rione Sant’Angelo in Rome, during the flood of the river Tiber. Painting by E. Roesler Franz. By Ettore Roesler Franz, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=131618

watercolorists and vedutisti (landscape artists) of the nineteenth century, who portrayed some famous views of Rome and its countryside. His famous watercolors are now exhibited in the Museum of Rome in Trastevere, and depict the old romantic and decadent Rome inhabited by peasants and working-class people, which was lost in the unification of Italy. This series of paintings was indeed named Roma Sparita (Vanishing Rome) because it portrayed a reality that no longer existed following the capture of the city in 1870 and the subsequent urban renewal plans. The everyday life of the poorer inhabitants of Rome—depicted in the old houses, the street markets, the clothes hanging—created an effect of sweet melancholy in the shadows of the ancient classical grandeur embodied in ancient wall sections and pieces of architectural decoration.

In the last 150 years, as it is easy to imagine, Rome has completely changed; however, the monumental center of the imperial city has been preserved almost intact over the centuries. Luckily, the area between the Palatine Hill, the Colosseum, and the Roman Forum has been the favorite place for local and foreign noblemen to build their villas, with wide urban gardens and vineyards, which has had less of an impact on the archaeological structures of the area, preserving most of them rather intact. Looking at nineteenth-century paintings and etchings depicting the Forum Romanum, we can see it completely covered with earth, with just the upper part of the honorary columns visible and flocks of cows grazing.

The Colosseum is another incredibly preserved structure and an iconic monument of Rome. It was built by the Flavian emperors Vespasianus and Titus in eight years (72–80 AD) on the ruins of Nero’s Domus Aurea, and was the biggest Roman amphitheater in the world.11 Despite many legends of the emperor Nero torturing Christians in the Colosseum, he was already dead when it was built (so he couldn’t see anyone dying in it). Due to its shape, in the Middle Ages it was transformed into a small fortified village that included a church, Santa Maria della Pietà al Colosseo, which is a sacred area still visible today on one side of the arena where the modern wooden cross stands. When the legends of Christians killed by beasts spread in medieval times—some Christians surely died in the arena, but as gladiators, just as any other religion affiliate—the Amphitheater needed to be purified from pagan influence. For this reason, a Via Crucis was organized every Holy Friday and it is still practiced today, representing one of the most fascinating Christian celebrations to be seen in Rome during Easter.

The situation is different in the Imperial Forum area, which is just a few steps away from the Colosseum and the Palatine. The construction of Via dell’Impero (the present Via dei Fori Imperiali) during the fascist era caused massive destruction to the ancient structures. Mussolini promoted the construction of a large triumphal road running in a straight line from Piazza Venezia to the Colosseum to connect the monuments of Imperial Rome with the Republican ones of Campo Marzio, and to connect it to Via Vittorio Emanuele II, the road opened by the Savoy (the royal house of Italy until 1946) after the unification of Italy. Via dell’Impero hosted military parades during the regime, and today the parades celebrate the founding of the Italian Republic.

The construction works for Via dell’Impero led to the hasty excavation of the Fora of Augustus, Trajan, and Nerva and the Temple of Peace. No archaeological information was recorded, and data of inestimable value for the reconstruction of the history of Rome was lost forever. The construction works, moreover, involved the almost complete destruction of an entire medieval quarter inhabited by the popular class, the Alessandrino district. The inhabitants of the neighborhood were considered “too dirty” to occupy such a glorious area, and were deported by the fascist regime to the Borgata San Basilio, a peripheral and poorly developed area in the eastern outskirts of Rome, which still today has severe social problems. The Italian writer Pier Paolo Pasolini recounted the life of the people living in these Roman suburbs in his books, emphasizing the detachment of the peripheries from the city center that no longer belonged to them. In his novels, the fictional characters living in Pietralata or San Basilio, when going to the Termini main station, talked of a trip to Rome as if they were traveling to another city.

Between the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth, the idea of what is called the “Passeggiata Archeologica” (Archaeological Promenade) was extended to include the Baths of Caracalla, which is still one of the most visited monuments of the city. Built by emperor Caracalla (188–217), who was famous for bestowing Roman citizenship on all the inhabitants of the empire, the Baths are probably the best-preserved thermae of antiquity. Nowadays in summer the baths are used for opera and classic music concerts.12

The largest Roman monument preserved is undoubtedly the Aurelian Walls, built between 270 and 275 AD by the emperor Aurelian and restored many times until the capture of Rome in 1870. Most of the original city gates from imperial times are still well preserved and visible, such as the Porta Asinaria. The Aurelian Walls gird the historic city of Rome and they still represent a physical limit between the center and the suburbs. Over the centuries, many buildings have been built over the walls, contributing to the romantic and distinctive landscape of Rome.

The stratified complexity of Rome is reflected in the organization of its museums and administrative bodies. Rome has two superintendencies—state and municipal. This distinction is rooted in the past; already in the sixteenth century the Papal State had organized offices dedicated to the protection of its cultural heritage, which was headed by the famous painter Raffaello Sanzio. Following the unification of Italy, the new state created territorial organizations for the protection of antiquity, which were named superintendencies. The Capitoline Superintendency of papal origin was maintained as a sign of respect for the history of this institution. In addition to the superintendencies of Rome, there is also the authority of Vatican City, which, as a sovereign state within the city of Rome, owns and manages the Vatican Museums. These are among the most visited museums in the world, displaying a large number of archaeological objects of inestimable historical value. Visitors who want to see the most outstanding archaeological collections of Rome can choose between the Capitoline Museums, divided into two locations and managed by the municipality of Rome; the National Roman Museum, divided into three locations and managed by the state superintendency; and the Vatican Museums, managed by Vatican City.

RISING FROM THE ASHES: POMPEII AND HERCULANEUM

On August 23, 79 AD, Vesuvius erupted, burying several cities in the Gulf of Naples area under a mantle of volcanic ash, killing thousands of people, and forcing the survivors to flee. Pompeii and Herculaneum are the two most famous cities that suffered this fate, together with Stabiae (today Castellammare di Stabia), and other smaller towns where there were rich landlord villas—for example, the famous Oplontis villa. Pompeii and Herculaneum were two of the Roman cities that had been extensively damaged in the past due to earthquakes, and ironically enough, they are also among the best preserved in the modern era. Pompeii is without doubt the best-preserved and best-researched ancient city of the Mediterranean and perhaps of the entire world. Two-thirds of the ancient city has already been extensively excavated.

Pompeii was founded by the Osci in the seventh or sixth century BC. After being placed under Greek and Etruscan political influence, Pompeii was put under Roman control from the third century BC, becoming the Colonia Cornelia Veneria Pompeianorum. Sulla conquered the city in 89 BC during the social troubles. In 62 AD an earthquake struck the city, causing extensive damage. When Vesuvius erupted in 79 AD, the city was still under reconstruction, as can be seen from the architectonic remains.

Pompeii was not buried by lava flows, but by ashes, a pyroclastic rain that lasted a few days and deposited a six-meter layer of pumice and ashes on the city. Excavations started at the behest of Charles III of Bourbon, King of Naples when Pompeii was rediscovered in 1748. It is estimated that of the approximately 1,150 bodies that have been excavated in the city since the eighteenth century, half died during the first stages of the eruption because there was no layer of ashes between the bodies and the floor on which they lay. The other half died sometime later, almost certainly asphyxiated by the gases produced by the volcano as they tried to escape.

The number of inhabitants of Pompeii at the time of the eruption is unknown. The estimates vary between six thousand and twenty thousand inhabitants. In any case, it was by no means among the largest cities of the Roman world, but an important provincial town, which was a commercial stopover on both overland and seaborne trade routes. Although it may seem strange to the eyes of modern visitors, Pompeii before the 79 AD eruption was facing the sea. The piers are still visible where boats and ships were anchored. The landscape indeed has changed significantly due to the activities of Vesuvius, and the coastline is today about two kilometers to the west.

From an architectural and town planning analysis, it emerged that Pompeii was not an overpopulated city, and at the time of destruction it had not yet had to deal with lack of space, as happened in other Roman cities, where buildings were constructed with an increasing number of floors. Walking along Via dell’Abbondanza, the decuman maximum of the city, indeed, one can observe that houses higher than one floor are rare, and many blocks within the third century BC city walls were even empty.

North of Pompeii and west of Vesuvius there is Herculaneum. The legend says that Hercules founded the city on his return from the Iberian Peninsula, where he had stolen a herd of oxen from Geryon. Archaeological research proved that the city was probably of Oscan origin, as the site was first occupied between the eighth and the seventh century BC.

Following Etruscan and Greek domination, the city went first to the Samnites and, in 307 BC, to the Romans. From this period, Herculaneum became one of the privileged places for the otium, the privileged classes, having more a residential character than a commercial one.

Unlike Pompeii, only one-fifth of its 20 hectares was excavated, as it had been covered not only by ashes, but also by a wave of volcanic mud with a thickness between eight and twenty-five meters, which had solidified to form hard tuff. Thanks to these geological circumstances, at Herculaneum organic materials such as wood and papyrus are amazingly preserved. The so-called Villa dei Papiri, which belonged to the Pisoni family, is famous for its collection of 1,826 documents on papyrus of inestimable value, which were recovered in the library of the villa. The villa was owned by the father-in-law of Gaius Julius Caesar, Lucius Calpurnus Pisone Cesonino, a follower of Epicureanism and protector of the Greek philosopher Philodemus of Gadara. In many houses, the carbonized remains of the wood used for the construction are preserved.

![Figure 4.9. Herculaneum, a view of the port area. On the right it is possible to appreciate the dimensions of the tuff rock covering the city. Sarahhoa [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]](../Images/chpt_fig_026.jpg)

Figure 4.9. Herculaneum, a view of the port area. On the right it is possible to appreciate the dimensions of the tuff rock covering the city. Sarahhoa [CC BY-SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)]

In Herculaneum we can also observe for the first time residential and commercial multi-floor structures. The so-called Insula Orientalis secunda is indeed a kind of four-floor building. Each floor was added progressively as the demand for space grew and it became impossible to expand the buildings horizontally.

Having been destroyed in 79 AD, Herculaneum, like Pompeii, presents the characteristics that towns would have assumed in that period: after the great fire in Rome of 64 AD, Emperor Nero made a law about city planning rules, to reduce the possibility of fires and collapses. One of these rules was a ban on building balconies without correct safety systems on the road, such as pillars or columns. That’s why we can still encounter many of these structures while walking around the city.

Visiting—or digging in—Pompeii or Herculaneum is like being in a freeze frame from the past. In one night, the survivor inhabitants of Pompeii, Herculaneum, Stabiae, and Oplontis were forced to flee from their houses, leaving behind all their possessions, and suddenly interrupting the actions they were performing. The houses, the shops, the temples, the public buildings, even the food they were eating, remain almost two-thousand years from that night.

The individual stories of the dead become in the eyes of the historian and the archaeologist collective events, as in the case of the three hundred people who died asphyxiated together on the pier of Herculaneum, while waiting for a boat to take them to safety offshore. Pliny the Elder, the famous writer, driven by his scientific curiosity, died on the beach of Stabiae having come too close to the place of the eruption.

Any archaeologist who has worked in Pompeii can tell you how thrilling it is to find items from 23 August 79 AD abandoned on the counter of a tavern, or observe tangible signs of illegal constructions made following the 62 AD earthquake, or discover a shell used to produce red dye while excavating the sewing system of a domus transformed into a fullonica (laundry and dyeing facility).

Such an enormous archaeological heritage, of course, has huge restoration and conservation problems as well as enormous monetary costs for research efforts and daily commitment. The archaeological parks of Pompeii and Herculaneum were declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1997. As is well known, this organization sets strict quality parameters for a site to remain on the list.

From 2001 the Archaeological Park of Herculaneum had been engaged in an international project for the conservation and restoration of the site, in collaboration with the British School at Rome and the Packard Humanities Institute. The latter invested more than 15 million euros in the project to monitor and restore the structures, which are highly degraded and in serious risk of collapsing. The project was a success and allowed the park to emerge from its state of crisis, soon becoming a reference point for the management of the relationship between the private and public spheres in safeguarding cultural heritage.

On 6 November 2010 in Pompeii the collapse of a large structure in the area of the Schola Armaturarum made plain to the whole world the deterioration of the ancient city. The structural problems were mainly due to the lack of constant and daily maintenance and a serious risk-prevention plan. These, in turn, were caused by the scarcity of economic resources and personnel at the park’s disposal. This and further minor damages had a wide echo in newspapers all over the world and were used by the media to denounce the state of the ancient city.

Since then, several Italian ministers of cultural heritage have taken actions in order to intervene by implementing monitoring and restoring plans for Pompeii. The last of these plans is the so-called Great Pompeii Project, initially launched in 2011, which led to the establishment of a technical council that supports the park director in taking the necessary measures to safeguard Pompeii. Since 2012 the project has been funded with European and national funds for a total of 105 million euros.

ANCIENT OSTIA, ROME’S GATE TO THE MEDITERRANEAN

Since antiquity the Tiber River was called flavus “the blond” in reference to the yellowish color of its water. It represented a key communication route connecting the city of Rome to the Tyrrhenian Sea. For this reason, Ancient Ostia was founded near the Tiber delta, in a key position for commerce. A huge amount of goods was shipped to Rome from around the Mediterranean transported by ships that docked in the port of Ostia. Since Roman times, the Tiber River has advanced at the mouth by about three kilometers, leaving the ancient port of Ostia six kilometers inland.

According to Roman tradition, Ostia was founded by Ancus Martius, the third king of Rome. The excavations in the ancient site, however, have not yielded traces of occupation prior to the beginning of the fourth century BC. This period coincides with the Roman conquest of Veii in 390 BC and its expansion beyond the Tiber.

When the natural area used for docking the ships was not sufficient anymore for the increased maritime traffic, two artificial docks were built by the emperors Claudius and Trajan to connect the port to the sea through an artificial channel. During the third century, the commercial emphasis shifted to the town of Portus, which was Ostia’s harbor district, situated a few kilometers to the north. Portus even became an independent city from the reign of Constantine.

The first building phases of the Roman colony visible today are part of the walls of the original castrum built of tuff from near the city of Fidenae and dating to the fourth century BC. From the late Republican period there are the remains of the Sullan walls and the area around the Forum, including the temples with a base in tuff, which were incorporated into some houses built subsequently.

In the imperial period, especially during the second century AD, the city flourished. This is the best-preserved phase, characterizing most Ostia’s appearance, with the red color of the bricks that pervades all the buildings, whatever their nature, residential, public, or sacred.

During its heyday Ostia must have had some forty thousand inhabitants, although in the periods of crisis starting in the third century AD this number must have decreased considerably, as commercial buildings along the Tiber and spacious apartments elsewhere in town were abandoned and left to collapse. Several commercial buildings in Ostia were modified drastically in this period and transformed into wealthy habitations. From the early fifth century, the city was in decline.

If Pompeii and Herculaneum represent a picture of urban architecture in 79 AD—a moment of great change in the residential system that invested the entire Roman world—the city of Ostia can give us a vivid idea of a further step in the evolution of Roman architecture represented by the Insula type house with several stories.13

Figure 4.10. Ostia Antica, Thermopolium in the Caseggiato with the same name. Di Marie-Lan Nguyen (User: Jastrow)–Opera propria, CC BY 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2970505

While the Roman elite and the very wealthy lived in a large single-family residence called a domus, ordinary people of lower- or middle-class status (the plebs) and all but the wealthiest from the upper-middle class (the equites) lived in insulae. In Roman architecture, an insula (Latin for island, plural insulae) was a kind of apartment building that housed most of the urban population. The ground-level floor of the insula, called the taberna (shop), was used for different types of commercial and recreational activities. The living space was separated and placed upstairs.

The tabernae consisted of rooms that were almost always large and rectangular, and were accessible from the street or from the interior of a building. In the facade sometimes there was a terracotta shop sign. The entrances to the shops had a characteristic threshold and lintel, having a groove for vertical shutters and a depression with a pivot-hole for a door.

In the excavated part of Ostia, more than 800 shops have been counted, while 577 have been found in Pompeii. This number gives us an idea of the large number of sailors and merchants who visited the shops at Ostia every day. Needless to say, there were also a large number of shops in which food and drink were served. Their main characteristic is the bar counter, with a vaulted water basin in its base that was accessible from both sides of the counter. The water in the basin was mixed with wine and used for cleaning crockery. Thirty-nine bars can still be identified at Ostia.

Ancient Ostia is one of the best-preserved and most extensively excavated Roman cities, although only 40 percent of the original surface of the city has been excavated. Excavations were carried out from the nineteenth century onward, uncovering about thirty-four hectares of urban fabric. Most of the phases later than the second century AD were destroyed because excavations aimed mainly at recovering masterpieces of classical art. This attitude dominated archaeological research in Italy for a long time, until the 1960s. The stratigraphy was not considered as a source of information, but simply rubbish that had to be removed to admire the monumentality of classical-age buildings. In the case of Ostia, what the excavators made visible corresponds to the buildings dated to the first half of the second century AD, the “golden age” of the port city.

Yet it was in ancient Ostia that at the end of the 1960s the stratigraphic method was applied for the first time in the excavation of a classical site in Italy. A team of young researchers excavated the Terme del Nuotatore (the Baths of the Swimmer), strongly influencing the excavation methodology in Italian archaeology up to the present time. These baths were built in the years 89–90 AD, during the reign of Domitian, and a major rebuilding took place during the reign of Hadrian and Antoninus Pius. The excavations also identified each phase on the basis of the analysis of different earth deposits that were formed during the phases of the life and abandonment of the structure. These were excavated following a stratigraphic order starting from the most recent layer to the most ancient one. The artifacts recovered in each of these layers were cataloged and studied together as an assemblage that could provide information on each period of time. The publication that followed the excavation was the first in Italy to present the excavated contexts in a stratigraphic way together with a complete catalog of the material culture that was recovered and information on the stratigraphic and contextual provenience of each artifact.

Ostia is also a key site for understanding the development of modern Italian architecture. The topographical and architectural study of the insulae of Ostia, indeed, inspired Italian social housing architecture in the 1930s. Popular neighborhoods and buildings built in Rome at that time were inspired by what Ostia had revealed with the excavations. The houses and insulae of Ancient Ostia were a source of inspiration for the rationalist architects of the fascist era, who sought in the forms of the imperial past a perfection that they wanted to transfer into contemporaneity.

HADRIAN’S VILLA: AWAY FROM THE CHAOS OF THE CITY

Animula vagula, blandula,

Hospes comesque corporis,

Quæ nunc abibis in loca

Pallidula, rigida, nudula,

Nec, ut soles,

dabis iocos14

This short poem was written by the Emperor Hadrian and tells of preparing himself to take leave of his soul before death. It was also used by the writer Marguerite Yourcenar for the title of one of the chapters that make up her masterpiece novel Memoirs of Hadrian on the life of the erudite emperor who lived between the first and second centuries AD.

Near the modern city of Tivoli, the ancient Tibur, stood the private villa of one of the most famous Roman emperors, the Spanish Hadrian, who reigned between 117 and 138 AD. Much has been written on Hadrian. He was known especially for the peace that characterized his reign after the stormy and warlike period of his predecessor, Trajan, and of course for his dedication to philosophy, which influenced the cultural and religious tolerance embodied in the construction of the Pantheon, the temple where all the gods of the empire, including Jesus Christ, were worshiped together.

![Figure 4.11. Villa Adriana, panoramic view of the area next to the Pecile, the Teatro Marittimo and the Thermae with Heliocaminus. gian luca bucci [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)]](../Images/chpt_fig_028.jpg)

Figure 4.11. Villa Adriana, panoramic view of the area next to the Pecile, the Teatro Marittimo and the Thermae with Heliocaminus. gian luca bucci [CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)]

Hadrian’s Villa was conceived as a luxurious retreat from the chaos of Rome. Its original area reached over three hundred hectares, and it is probably the most famous of the works executed by Hadrian during his reign. Since its rediscovery in the mid-fifteenth century Hadrian’s Villa has represented a point of reference for the nobility and the clergy, an ideal model of a residence for the otium15 that an enlightened despot like Hadrian could afford.

The Historia Augusta (Augustan History) is a late Roman collection of biographies of the Roman emperors. It tells us that Hadrian tried to emulate various famous natural and man-made landmarks from around the Roman Empire that he had visited during his journeys: “Tiburtinam Villam mire exaedificavit, ita ut in ea et provinciarum et locorum celeberrima nomina inscriberet, velut Lyceum, Academian, Prytaneum, Canopum, Poicilen, Tempe vocaret. et, ut nihil praetermitteret, etiam inferos finxit.”16

Many of the monuments composing the Villa were named after the list given in the Historia Augusta, by the scholars who investigated the Villa in the fifteenth century. However, none of these identifications should be taken for granted, even if for some of them the name seems likely.

The Villa was conceived as an autonomous city, with service and residential districts kept physically separated but connected by precise routes of passage. The most modern architectonic concept of the villa, indeed, was precisely that of its paths, which were separated on the basis of who had to cross them, with those for service dislocated on different levels. In this way servants and workers were hidden from the eyes of the villa’s guests. We will have to wait for Leonardo da Vinci’s projects in the fifteenth century to have a similar modern conception of different spaces within a unique architectonic structure. Romans paid careful attention to the way in which they moved through their society, as the culture of walking in ancient Rome is connected to the performance of social status.17

During the decline of the Roman Empire in the fourth century, Villa Adriana gradually fell into disuse. In the Middle Ages it was plundered and ransacked. The statues and the marbles were reused to decorate the buildings of Tivoli, and the site was used as a quarry of materials from which to obtain lime.

In the mid-sixteenth century Pirro Ligorio was the first to make a relief of the villa, commissioned by Ippolito d’Este, for whom he also procured many precious materials to adorn the newly constructed Villa d’Este and other villas in Tivoli and Rome.18

Since 1999, Hadrian’s Villa has been inscribed in the UNESCO World Heritage Site list, although a series of construction works in the vicinity of the Villa has created disappointment in the international organization and the inscription of the site seems to be hanging on by a thread.