CONTROVERSIES IN ITALIAN ARCHAEOLOGY

Like every scientific discipline, archaeology has its controversies when it comes to the interpretation of past events. Archaeology indeed focuses on a wide range of social dynamics, including cultural changes, the origins of civilization, the origins of agriculture, and other similar themes. Archaeologists make the connection between particular actions and practices and an expected archaeological pattern on the basis of a rich and diverse array of methods. Topics like the Neolithization of Italy, migration patterns in the Mediterranean during the third and second millennium BC, the emergence of Etruscan civilization, the proto-urban phenomenon and the birth of Rome, and the invention and transmission of innovations are among the topics of heated debates by scholars worldwide.

However, controversies connected to archaeology are by no means limited to academia. Archaeology is a discipline that lends itself well to being used—and often misused—as a tool to foster feelings of belonging and continuity that are at the base of building a national identity. The physicality of archaeology, indeed, gives an added sense of material reality to emotions and feelings involved in identity building. The archaeological record is assumed to provide tangible proof of the past, which can be conceived and interpreted as a physical representation of the concept of identity. Archaeology has also occupied a preeminent place in territorial disputes based on the precedence of a group over a given territory, providing the tangible proof of those claims. Archaeology also occupies a prominent place in popular culture, as the discipline’s practitioners are perennially bombarded with questions about the mysteries of the past. Archaeology fascinates many in the contemporary Western world, and countless publications and TV programs engage with archaeology’s results.

As Cornelius Holtorf observed, archaeology is ubiquitous because archaeology digs not only into the ground but also into a number of significant popular themes. These are perceived as relevant because they can tell us a lot about ourselves, about who we are, about our “collective memory.” Through the memory, indeed, we re-present the past of our culture, region, or species. Archaeological sites are places in which memory crystallizes in the present, transporting the past into people’s everyday life.1 For this reason, archaeology increasingly engages with the way in which different communities remember and appropriate the past, which can be substantially different from the perspective of academic archaeologists and heritage experts. The relationship between the past and the present can be also strongly influenced by fantastic theories called pseudoarchaeology (fantarcheologia in Italian), which also plays a role in the building of identity in local communities.

Controversies in archaeology also pertain to the realm of international relations and international law, which concerns the illicit trade of looted antiquities. The black market of antiquities is a huge problem in Italian archaeology, especially in some areas of the country, such as Etruria or Sicily. The repatriation from the United States of Italian archaeological artifacts such as the world-famous Euphronios krater and the treasure of Morgantina represent two of the most famous controversies of this type. The most famous case of a legal controversy regarding ownership is undoubtedly the dispute over the Elgin Marbles between Greece and England. But the looting of Iraq’s archaeological heritage is an example of the ineffectiveness of international law to stop illicit trafficking.

Following the outbreak of the 2003 hostilities in Iraq, the National Museum in Baghdad was ransacked. The official US investigation reported that at least 13,515 objects had been stolen from the museum. By June 2004 only 4,000 had been recovered, while the others were sold on the black market to collectors worldwide. Although different, these two examples have as a common trait the interplay between international politics, diplomacy, archaeology, and identity building. The same intricate situation can be observed in Italy.

Finally, one vigorously debated issue concerns the effects of mass tourism on Italian archaeological heritage. Tourism continues to develop as a significant social and economic activity, as it represents one of the most important industries in the global economy. The struggle is to find a balance between use and conservation needs, which is not always an easy task.

THE ETRUSCANS CONTROVERSY BETWEEN ARCHAEOLOGY, POLITICS, AND ANCIENT DNA

The Risorgimento was the political and social movement that consolidated the different states of the Italian peninsula into the single state of the Kingdom of Italy in the nineteenth century. The term also designates the cultural, political, and social movement that promoted unification, and recalls the romantic, nationalist, and patriotic ideals of an Italy unified by a political identity rooted in the Roman period.

Roman classical antiquity was utilized for identity-building purposes as early as the Enlightenment era, and in the following Napoleonic period the cultural debate started to be centered on the concept of the autochthonism of the Italians. However, in the same epoch, pre-Roman identity also started to become increasingly important. The issue of the pre-Roman origin of the Italians was deeply permeated with ideology, and it was part of the general cultural debate on the identity of the Italian nation. The first book dealing with antiquity, ethnogenesis, and autochtonism was Vincenzo Cuoco’s Platone in Italia (1806). This book is the first of many arguing that the Etruscan people represented the ethnic and cultural core of the Italian nation and that they had a cultural primacy with respect to Greeks and Romans. The “discovery” in the eighteenth century of pre-Roman Etruscan antiquity for identity-building purposes also developed in the following centuries and privileged the Etruscans as the first civilization of Italy in opposition to the Greek colonists who occupied the south of the peninsula and to the Roman “newcomers.” Between the nineteenth and the twentieth century, the autochthonism movement insisted on the key role of the Mediterranean as the origin of the Italian and European civilizations, projecting the relevance of Italic Etruscan people in a wider historical framework. This Italian trend was comparable to the one observed in other European countries, above all Germany and France, where in this period intellectuals created a national history based on antiquity.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, relevant issues concerned the ethnic homogeneity of Italy and racial differences were debated inside and, most notably, outside academia. The fascist empire drew its force from the past, as the Romanità, the idea of a heritage directly deriving from ancient Rome, was central to fascist ideology, and it was largely employed to foster Italian identity building.2 In this period, the opposition between a primordial Etruscan identity and a primordial Roman one needs to be seen as the confrontation between two possible nationalisms: one built on the first Italy, and the other on Roman hegemony. The fascist regime made its choice, emphasizing the romanocentric and imperial ideology, while the scholars dealing with the Etruscans made their own. Attempts were made to connect Etruscan art with fascist politics to resolve this tension. In 1926 Mussolini attended the inauguration of the Novecento Italiano exhibit in Milan. The statue depicted on the exhibit poster was the Etruscan Apollo excavated at Veii, in 1916. In the 1920s, this masterpiece represented the vivaciousness and creativity of Etruscan art, but over time, proponents of racist ideology found it difficult to incorporate Etruscan origins with the purity of Romanità, and appreciation of Etruscan art and culture weakened. In 1937, G. Q. Giglioli organized the exhibition Mostra augustea della romanita, discussing the concept directly with Benito Mussolini himself. The scholar, however, also produced several volumes focusing on the Etruscan arts without perceiving any political contradiction in his scholarly love for the Etruscans, which he called the “prima giovinezza della Nazione” (first youth of the Nation).3 The general tendency was indeed to Italianize the Etruscans and to Italianize the Italic people—that is, to make Etruscan civilization the first page of the history of Italy.

A key figure of this period is the etruscologist Massimo Pallottino.4 In Pallottino’s view of the origin of the Etruscans—a conception that is generally accepted among Etruscan archaeology scholars today—the Etruscans are thought to be the result of a long formative process involving different populations and various events. This idea of ethno-genesis was expressed in 1942 in the first edition of Etruscologia, a book published by Pallottino in the context of a fierce struggle over the definition of the origins of the great European nations. The great Italian scholar, while promoting an Etruscan ethnicity that extended as far as the confines of Europe, began his book with a foreword with openly nationalist undertones.5 The Etruscan studies during the fascist era were somewhat controversial, but they were nevertheless absorbed under the ideological umbrella of the Romanità, despite scholarship and personalities at times conflicting with the political regime. Contrary to Nazi politics in Germany, which caused more damage because of the anti-Semitism that forced many scholars to leave Germany, Italian fascism definitely affected scholarly circles, but not as extensively. Although better known for his research on Etruscans, Massimo Pallottino also played a role in defining the Italian presence in North Africa.6 By using Roman colonization in antiquity as a model of success due to the supremacy of the colonizers over the local populations, in his articles published in Rassegna Sociale dell’Africa Italiana between 1938 and 1943 he highlights the history and traditions of both cultures while at the same time perfecting his interpretation of the origin of Etruscan culture in Italy. Since the mid-twentieth century a convincing academic consensus has been built that the Etruscans were an autochthonous people.

After the Second World War, Etruscology as scientific discipline slowly freed itself from conservative ideology, and the discussion of the origins of the Etruscans was completely abandoned, as it represented almost a taboo in archaeological research until the 1990s. The negative attitude toward migration of Renato Peroni and his School also contributed to this lack of study.7 Like Pallottino, Peroni was a charismatic and powerful figure, although of completely different ideological background. He adopted a Marxist approach to the study of the Italian protohistory and was not keen to accept any allogeneic inference in the explanation of cultural change. Migrationist hypotheses were thus systematically discharged, as was every Etruscan ethnic connotation of the Iron Age Villanova culture. Both Pallottino and Peroni, the first a vehement Catholic nationalist, the second a vehement atheist Marxist, had in common the refusal of superficial and banal interpretations of the archaeological record that often only aimed at confirming ancient sources.

A great revival of topics regarding the origin and migrations of the Etruscans, along with the consequent challenging of the assumption that the Etruscans were an autochthonous people, occurred in combination with the rise in importance of genetic and population studies. Since about 2000, indeed, the study of population genetics has made significant advances in its methodology. The first major investigation of the Etruscans’ ancient DNA (aDNA), published in 2004, involved eighty samples of bone from ten cemeteries in Etruria along with samples from Adria in the Po Valley and Capua in Campania.8 The investigation sought to answer two crucial questions: Were the Etruscans a biological population or just people who shared a culture but not ancestry? Also, what is their relationship to modern populations, and are they linked to other Eurasians? The first question directly addresses the basic assumption that the Etruscans were a nation, which is rarely questioned in Etruscology, since the Roman sources identify the Etruscans as a group, even if subdivided into different subgroups. Research shows that there is no clear Etruscan “genetic fingerprint” that could be detected. The research also suggests that the Etruscan aDNA samples had a shared set of ancestors, and this is consistent with the existence of a social structure based on bloodlines that is directly observable in Etruscan names and in family chamber tombs that were used over several generations from the Late Orientalizing period onward. At a more general level, the findings are consistent with Etruscan autochthony, since cultural and settlement continuity from the Late Bronze Age to the Etruscan period would generate a shared ancestry extending over at least ten generations. However, more recent work published in 2014 has identified a component of Near Eastern DNA in Tuscan samples, estimating that the genetic material mixed into the pool between 600 and 1100 BC.9 As the authors of this study note, these are estimates, and various historical circumstances may have led to the formation of the observed dataset. From an archaeological point of view, eastern genetic material in Italy is not to be unexpected in that period, and does not do anything to prove migration from Anatolia to Etruria. In sum, none of the DNA studies to date conclusively proves that Etruscans were an intrusive population in Italy that originated in the eastern Mediterranean or Anatolia. Likewise, there is no conclusive proof that present Tuscans are descended from Etruscans. On balance, there are indications that the evidence of DNA can support the theory that Etruscan people are autochthonous in central Italy. The absence of decisive results derives from the fundamental fact that archaeologically defined ethnicities do not neatly map onto patterns in genetic diversity.10

DEALING WITH THE COLONIAL PAST

The Italian colonialist enterprise started in 1882, when the Italian government acquired from a private navigation company the port city of Assab Bay on the Red Sea. At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Italy had acquired a large protectorate in Somalia and administrative authority in formerly Turkish Libya. In the Mediterranean, Italy also possessed the Dodecanese Islands, established a protectorate over Albania, and, during World War II, occupied Greece and Yugoslavia. The use of archaeology to legitimize occupation and political claims over colonial territories characterized the entire Italian colonial period, but was pushed especially by the fascist regime, as antiquity served as legitimization and example for the newly established fascist empire in the fostering of national identity in the peninsula. The myth of Romanity was based on the idea of a direct connection between late Republican and early Imperial Rome and fascist Italy. Most of Italian military actions in the Mediterranean Sea were preceded by archaeological missions, which were utilized in both domestic and foreign propaganda.11

The case of the archaeological mission in Libya is an emblematic example to understand the ambiguous relationship between power and academia, and to illustrate an important chapter in the history of Italian archaeology as a discipline.

Declaring war on Turkey, the liberal government of Giovanni Giolitti started one of the last great colonial wars. Archaeology entered in the Italian collective imagery in the idea that as successor of the Roman Empire, Italy had the right to “take back” Libya from the Turkish Ottoman Empire.

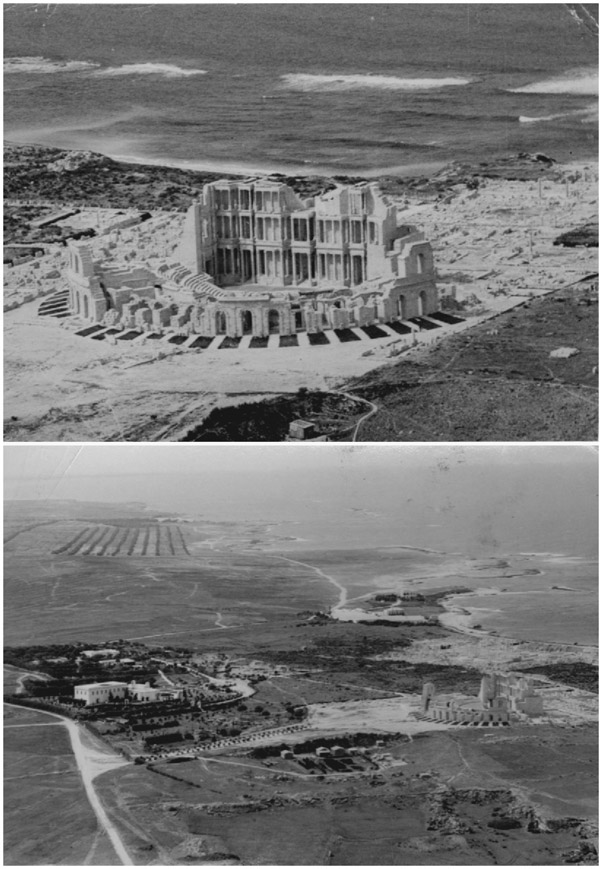

Figure 7.1. Sabratha, Libya, in Italian army imagery during World War II. Di Rademeig–Opera propria, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=26968671

The first archaeological structures were discovered during military operations in the Italo-Turkish conflict (1911–1912) and in the following years (1913–1923). The archaeological remains in the field of military actions represented an immediate resource, as they served both propaganda purposes—when the soldiers came across finds of outstanding value—and as building material, as the army reused and spoiled ancient structures to build military facilities. On the other hand, thanks to the interest of some army members, during the first years of the Italian occupation, military topographers of Italy’s Military Geographic Institute drew up topographical maps of the ancient urban areas on a scale of 1:12,500. From 1923, ambitious archaeological campaigns at Sabratha and Leptis Magna were inaugurated. The excavations, however, were conducted with non-stratigraphic methods, and the ensuing restorations, pushed for propaganda purposes, proceeded with extreme rapidity, causing the loss of large amount of data. During the work the idea of the possible exploitation of ancient ruins for touristic purposes also gained ground, and several efforts were made to promote Libya as a touristic destination by publishing tourist guides and disseminating the images of antiquities in picture postcards. Monuments such as Sabratha’s Theater, the Forum, and the great Basilica of Justinian entered the popular imagination of Italians. The Theater in particular was restored and reconstructed with the aim of making it once again viable as a site for performances, becoming the icon of Sabratha. Being undertaken with a clear political agenda in mind, the excavations were not matched by an equally prolific production of scholarly publications.

The outbreak of the Second World War led to a change in the visitors to the Libyan archaeological sites. Tourists disappeared, giving way to soldiers from both Italy and Germany. The main concern of the deputed authorities in this period was the preservation of the site from the enemy and from damage caused by military operations. When the allied troops reached Sabratha, two British archaeologists, Lieutenant Colonel Mortimer Wheeler and Major John Bryan Ward-Perkins,12 received the surrender of the personnel of the Italian Soprintendenza, which was now placed under the direction of a British archaeologist, an official assigned to antiquities within the British Military Administration (BMA).

The first archaeological mission in Tripolitania in the postwar period was that of the British School at Rome (1948–1951). Already by the autumn of 1943, the Italian Empire and all dreams of an imperial Italy had come to an end. In 1947, the Italian Republic formally lost all its overseas colonial possessions. After Libya gained its independence from Italy in 1951, its rulers neglected archaeological research and sites, largely because they associated the archaeology with the colonial period. In 1969 Muammar al-Gaddafi took power in Libya and expelled the Italians still living there.13 Gaddafi was convinced that Greek and Roman architecture had nothing to do with Arab Muslim culture and identity. Over the past decades, however, archaeology has bloomed again in Libya, with more international missions allowed into the country. Among these were Italian archaeological expeditions, such as the survey project of the Archaeological Mission of the University of Rome, which started in 1995 and aimed at understanding patterns and trends of settlement since the earliest forms of human presence up to contemporary times. The situation of cultural heritage in Libya was already fragile before the revolution broke out in 2011, mainly due to the indiscriminate urbanization of the last decades; thus looting and lack of control and protection was prevalent.

Following the Arab Spring, Libya experienced a full-scale revolt beginning in 2011 and leading to the end of the Gaddafi regime and to the country’s political instability. The Italian–Libyan Archaeological Mission in Acacus and Messa researching prehistoric archaeology and rock art was the last foreign archaeological mission to leave Libya, as they were working in the desert hundreds of kilometers away from an airport. In a Twin Otter light aircraft, they made their way at short notice to Sebha airport in central Libya to rendezvous with the evacuation plane, a C-130 Hercules military aircraft that escorted the Italian Archaeological mission safely to Rome.

The recent civil war also resulted in deliberate destruction, ideological and religious in character, of marabouts—rural religious architecture of the Karamanli/Ottoman age and primary elements of the cultural landscape of Tripolitania and more generally of North Africa. These have disappeared almost everywhere, targeted for destruction by Salafi fundamentalists.14

The legacy of Italy’s occupation and of Italian archaeology in Libya remains controversial. From the point of view of the scientific discipline, while Italian archaeologists have focused on crafting a critical historiography of archaeology under fascism, with a few notable exceptions they have mostly ignored the political role played by archaeology in Italy’s former colonies. The legacy of colonial archaeology in the present day remains indeed a mostly underexplored niche argument and has never been made an object of research and self-reflection within the discipline. This comes, however, as no surprise given the general lack of debate on Italy’s colonial past. Notwithstanding Gaddafi’s rhetoric, Italian colonialism in Libya still represents a strong and under-investigated case of social forgetting. While Italian schoolbooks barely mention this past, historical research has revealed that at least one-eighth of the Libyan population died as a direct result of the Italian occupation between 1911 and 1943.15 In 2008 Italy and Libya signed a highly controversial treaty that was designed as compensation for mass crimes perpetrated during the colonial period. Italy agreed to pay more than US$5 billion as reparation for the harm done to Libyans under the ruthless Italian colonial rule between 1911 and 1943. The Italy-Libya Friendship Treaty, however, provided financial aid to the country in exchange for Libya’s collaboration with Italy and the EU on migration control and in strengthening European external borders—in other words, for assuming the role of Europe’s gatekeeper. The agreement stimulated no public debate in Italy about colonial history; on the contrary, it short-circuited the production of social memory and actually has led to systematic violations of human rights against migrants and refugees.

THE MONT’E PRAMA GIANTS

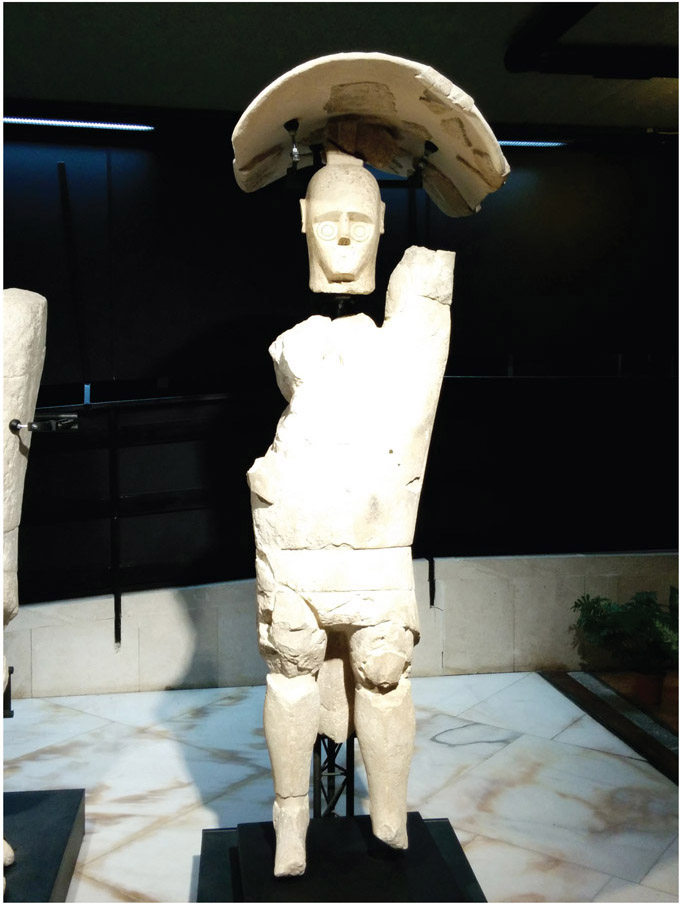

The Sinis is a small and picturesque peninsula in western Sardinia. It is extremely rich in archaeological remains, as it has been densely inhabited from prehistory onward: in the Bronze Age by Nuragic communities, subsequently by Phoenicians, and then by Romans. In 1974, some chalky sandstone statues were recovered by chance in a farmland on the slopes of Mont’e Prama, a hill on which a nuraghe sits at the top. These statues depicted a group of people interpreted as warriors because of their equipment, consisting of weapons and armors. Their height was between 2 and 2.5 meters, and for this reason they were called giants. About five thousand pieces were recovered, including fifteen heads and twenty-two torsos. In addition to these statues, a large number of fragments belonging to about thirteen nuraghe models were also found.

Those statues date generally to the Nuragic Age, between 1900 and 730 BC, but their precise chronology is yet to be defined. The Nuragic Age is named for the nuraghe, which is the main type of ancient megalithic edifice found in Sardinia during that period. It has the outer shape of a truncated conical tower with a tholos-like vault inside.

Subsequent excavations uncovered a large necropolis composed of shaft tombs and divided into two main areas, one of these flanked by a paved road. The corpses had been placed in sitting and crouching positions. Anthropological analyses showed that the remains belonged to both male and female individuals, which were mostly between thirteen and fifty years old. Fragments of the sculptures have been found on top the necropolis. The excavations remained unpublished and the statues were kept in a repository in the basement of the Archaeological Museum of Cagliari for about thirty years.

In the mid-2000s, thanks to the initiative of the former director of the Sardinia Superintendence, Antonietta Boninu, the statues were finally restored, and interest in the Mont’e Prama giants started growing. The works allowed for the identification of forty-four different statues, thirty-eight of which were recomposed from several fragments. The connection between the Mont’e Prama statues and the famous Nuragic bronzes was taken for granted, even if it was not yet clear which of the two crafts influenced the other. The dating of the “giganti” varies between the eleventh and eighth centuries BC. If further confirmed, they would be the most ancient anthropomorphic sculptures of the central and eastern Mediterranean, preceding the kouroi of ancient Greece.

The association of the statues to the necropolis is almost certain, even if there are other hypotheses that interpret the statues as parts of a nearby sanctuary, which however has not yet been yet identified. As most of the fragments were recovered by the local peasants and piled up as the plowing of the fields proceeded, the original locations of the statues are not clear. One hypothesis is that the statues were lined up along the road above the slabs that covered the shaft graves; the other is rather in favor of their placement in groups. The last hypothesis draws from a parallel with the Tombe dei Giganti (Giants’ tomb), a type of megalithic gallery that served as a collective grave, widespread in Sardinia during the second millennium BC.

Mont’e Prama was the site of new excavation works between 2014 and 2015. The trenches excavated in the 1970s were reopened and the researched area was further expanded, leading to the discovery of new statues as well as other nuraghi models. The excavation of an area looted in ancient times and then reused allowed for dating the abandonment of the site to the fourth century BC, thanks to potsherds belonging to Punic amphorae recovered in a secure stratigraphic context. Excavation was also conducted on new burials. The organic material recovered in these contexts was dated with radiocarbon to between the twelfth and the ninth century BC. Unfortunately, the absolute dating has not been able to narrow down the time span to less than four hundred years. This still open chronological issue makes it difficult to study and understand the social, cultural, and political context that led to the creation of the statues and the necropolis, since it spans a period of splendor in the Nuragic civilization and its crisis.

Currently the statues and other archaeological artifacts found at Mont’e Prama are divided between the National Archaeological Museum of Cagliari and the Civic Museum Giovanni Marongiu of Cabras, which is in the Sinis territory where the statues were excavated.

The long span of time between the first and the new excavations, and the apparent disregard for the unique context of Sardinian and Mediterranean archaeology caused controversies. In particular, the local community of Sardinia together with many archaeology amateurs felt that their own culture and traditions had been neglected by “official archaeology.” Sardinians have a strong identity as islanders, and this identity has roots in the opposition to the imposing of Italian identity that occurred following the unification of the country in 1861.

Figure 7.2. One of the Mont’e Prama giants, a warrior with a shield. Di Prc90–Opera propria, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=38340982

Sardinians feel that their own culture and traditions, including the archaeological past, have been overshadowed by Italy. In this way they believe that the indigenous archaeology of Sardinia, the Nuragic civilization, has been neglected by the Italian government in favor of the interest of the Italian Superintendence and “official archeology” for “higher” foreign cultures such as the Greeks, the Etruscans, the Phoenicians, and the Romans. The nineteenth-century Italian Risorgimento, indeed, promoted the country’s cultural unity on the basis of a strict classicist cultural conformism.

The story of the Mont’e Prama giants triggered in the local community national and sometimes nationalist feelings based on the reclaiming of the “true history of the island.” Some Sardinians are convinced that the lack of interest in Mont’e Prama by the Superintendence had a political context. The uncertainties in the interpretation of this exceptional discovery by “official archaeology” are seen as an attempt to hide and neglect the greatness of Sardinia’s past for fear of having to acknowledge it. There are several conspiracy theories that are popular in Sardinia today that claim that Italy wants to keep the island devoid of history by emphasizing the greatness of conquerors such as the Phoenicians and the Romans, who were foreign rulers of the Sardinians. Hence there is an increase in the popularity of theories that identify the ancient Nuragic people with the Shardana, one of the Sea Peoples mentioned in the Egyptian sources of the time of Ramses II who were among those who put an end to the Hittite Empire and put the Egyptians in difficulty.16 Albeit fascinating, this theory has no scientific basis, but archaeologists and enthusiasts have tried for years to prove it, and for some Sardinians it became an unquestionable truth connected to their identity. These theories are for the most part completely detached from the archaeological evidence, and in some cases, they resulted even in a witch-hunt against archaeologists working for the state, who were publicly accused of falsifying history. The case of what is known in Italy as “Sardinian pseudoarchaeology” should be a warning about the importance of the choices that are made in the managing of excavations and research, and in the way in which archaeology is communicated to the public. The role that archaeologists have in society cannot be underestimated, as they seek to establish the affective connection between the local society and the past that is materialized in the archaeological record. Issues concerning the rights of local communities that have a strong desire to be informed and made aware of how public money is spent in the research, are strongly debated in Sardinia. It will be the task of the Italian and Sardinian archaeologists to patch things up with local communities by making their research available and comprehensible to the citizens, especially to those without an academic background.

As the International Convention of Faro on cultural heritage also states, local communities must take an active part in the system of protection and enhancement of the territory and its history. Archaeologists have the task of understanding how to be part of this evolution in the relationship of a society with its collective past.

LOOTING AND BLACK MARKET

Because of its exceptional wealth of archaeological remains, Italy is one of the European countries most affected by tomb theft to satisfy the ravenous international art market. Indeed, a significant proportion of the ongoing destruction is brought about by looters acting from commercial motives, who are financed indirectly by private collectors of antiquities. These antiquities are sold without provenance, so that the true nature of looted artifacts is hard to discern, and many of these are ultimately acquired by major museums in Europe and North America. These collectors sometimes find their collecting activities tacitly encouraged and even legitimized by some prominent museums in Europe, in the United States, and in Japan.17 Even if some major museums have put in place ethical acquisition policies that prevent their acquiring recently looted artifacts, Colin Renfrew, one of the most renowned archaeologists for years on the frontline against illicit traffic of antiquities, argues that academic and museum communities have been insufficiently active in persuading more museum directors and trustees of their duty not to permit the acquisition by museums of artifacts labeled as “unprovenanced,” that are, in all probability, looted.18 The majority of looted artifacts, however, are traded privately, meaning these activities are invisible, except when the police or the Carabinieri19 seize looted artifacts or, in rare cases, access is granted by market insiders.

Looting remains in Italy is still a profitable business. Giacomo Medici is perhaps the most famous of Italian tomb raiders, the so-called tombaroli. His business was thought to be one of the largest and most sophisticated antiquities networks in the world. He was responsible for illegally digging up and spiriting away thousands of archaeological masterpieces and passing them on to the most elite buyers in the international art market. For nearly forty years, Medici and his gang organized the systematic looting and theft of innumerable archaeological artifacts, “laundering” these stolen objects through corrupt international dealers and major auction houses, who in turn sold them on to major institutions and collectors around the world.

The best-known artifact linked to Medici is the so-called Euphronios or Sarpedon krater, an Attic red figure vessel used for mixing wine with water. Created around 515 BC, it is the only complete example of the surviving twenty-seven vases painted by the renowned Euphronios, one of the most famous ceramic artists of the ancient world, and is considered one of the finest Greek vases in existence. The krater was eventually shown to have been looted from a previously unknown Etruscan tomb in the Greppe Sant’Angelo near Cerveteri in December 1971 and later sold by Robert E. Hecht, an American antiquities dealer living in Rome, to the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1972 for the then record price of US$1 million. Evidence suggests that Hecht may have purchased the krater in 1972 from Giacomo Medici. The routing of the material through transit countries to provide the appearance of legitimacy in destination countries is a characteristic feature of the antiquity trade. A possible parallel to the object laundering that characterizes the antiquity trade can be found in the trafficking of blood diamonds.20

Figure 7.3. Archaeological structures emerged during the excavation for Piazza Municipio Station. Di Sailko–Opera propria, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=75059074

In 2006, following the trial of Giacomo Medici, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Italian government reached an agreement under which ownership of the Euphronios krater and several other pieces of art was returned to Italy in exchange for long-term loans of other comparable objects owned by Italy. The krater arrived back in Italy in 2008, and it was displayed at the Villa Giulia National Etruscan Museum in Rome from 2008 to 2014 until it was moved as part of a temporary display in the Cerveteri Museum on the occasion of the UNESCO World Heritage Site affiliation for the necropolis at Banditaccia.

There are different levels in addressing the issue of illicit trafficking in archaeological heritage. One is concerned with the international demand for cultural objects from Italy by wealthy countries. The demand is related to European identity and to the role that the Greek and Roman past played in constructing the idea of the dawn of European civilization, and thus to the high symbolic value of possessing such heritage. The nineteenth century was the period when European colonial powers collected and appropriated most of the antiquities from their colonies around the world. European colonial powers appropriated the pasts of Mediterranean countries and considered themselves the unique heirs of the classical world. Roman antiquity served both as a national model of unification and as the political example for European imperial powers to follow. Similarly, ancient Romans and Greeks were seen as the ancestors of the new inhabitants of the United States as early as the eighteenth century, when the democracy of the independent nation was building. As a consequence, Greece and Italy have been the countries most affected by the looting of antiquities since the nineteenth century, and their cultural goods ended up mostly in the countries that developed and promoted this identity discourse, such as the United Kingdom, Germany, France, and lately the United States.21

The second level of analysis is related to Italian national heritage policies, as Italy suffers from a chronic lack of financial resources in the cultural sector. Protection, preservation, and promotion of Italian cultural heritage are complicated issues, as neither the superintendents nor the Italian police can implement the necessary measures.

Ancient Etruria, which is today divided between Tuscany and northern Lazio, is one of the areas most affected by the activities of the tombaroli, as it has numerous rich cemeteries, such as the Necropoli dei Monterozzi in Tarquinia, and the Necropoli della Banditaccia, in Cerveteri. In September 2013 a remarkable tomb was discovered in the necropolis of Tarquinia, eighty kilometers north of Rome, which contains roughly six thousand rock-cut tombs. The tombs, which date to about 600 BC, contained two sets of skeletal remains lying on two platforms, pottery, numerous metallic and terracotta objects, and other artifacts. Early reports suggested that the body that occupied a more prominent position and was buried with a spear belonged to a man; however, further analysis demonstrated that it was indeed a thirty-five-to-forty-year-old woman. These finds are important for advancing our understanding of Etruscan culture in central Italy, but what is most remarkable about this discovery is that it exists at all.22 The Tarquinia discoveries are also a stark reminder about what we lose when archaeological sites are destroyed and stripped of objects. The Necropoli dei Monterozzi in Tarquinia and the Necropoli della Banditaccia in Cerveteri were designated World Heritage Sites in 2004. The former includes the whole Monterozzi funerary area, while the latter includes only one of the funerary areas of Cerveteri, leaving aside about four hundred hectares of ground full of tombs that lie exposed.

At the end of the eighteenth century, excavations in search of ancient masterpieces of art were encouraged in Tuscany by foreign enthusiasts and directed by landowners. Local farmers and peasants who worked the fields were those who carried out such excavations. Lately, those local people started to work on their own, only in some cases with the consent of the landowners. Being a tomb raider, a tombarolo, was another way of obtaining additional income for the lower classes. It soon became a generational career, transferred from father to son together with the skills necessary to locate the best archaeological sites to loot on grave-robbing expeditions. The oldest tombaroli teach new generations where, when, and how to excavate, guided also by a passion for the Etruscan past, as the looters feel they are spiritually guided by their Etruscan forefathers in their tomb searches. At first sight, this can seem a contradiction. However, because the tombaroli perceive the Etruscan culture as the basis of their identity and thus Etruscan necropolises as their own property, they feel they have the right to sell archaeological artifacts to rich foreigners.

The number of looted tombs is enormous. The Italian police have found that one of these tombaroli has sold five times more black figure vases than the total number that exists in the Villa Giulia Museum in Rome. In the 1970s, more than eighteen “teams” of tombaroli worked in the territory of Tarquinia and Cerveteri. Today, thanks to the implementation of laws against looting and trafficking, there is only one team left. This reduction is also due to the decline of international demand, as well as the presence of looted archaeological artifacts from Iraq and Syria on the black market.

THE CHALLENGE OF MASS TOURISM: POMPEII AND ITS RUINS

With the widespread popularity of heritage places as tourist attractions, destination planners and government agencies have realized the potential financial benefits of developing archaeological heritage sources for tourism. While the popularity of archaeological heritage sites as tourist destinations may result in the enhancement of different extraordinary conservation programs, on the other hand it commonly leads to heritage conservation being motivated by the need for revenue alone. In other words, the main message that gets across in Italian society is that conserving the past is good for business and can contribute to a region’s economic growth and stability. Archaeological heritage, indeed, when it does not represent an income source is largely ignored, and it is perceived as irrelevant without an economic justification.23 One may thus argue that tourism is always positive when it comes to archaeological heritage because it produces an income that can be allocated to the sites’ conservation. Yet popular archaeological sites that are renowned touristic attractions are among the most endangered ones, exactly because of the massive number of tourists who visit them.

Let’s take a brief look at some statistics concerning Italian cultural tourism. Italy is at fifth place in the world as concerns international arrivals for touristic purposes. Tourism represents about 9–10 percent of the GDP, and gives work to about 2.5 million people. Cultural tourism is growing steadily despite the economic crisis. In 2010 it represented 34.6 percent of Italian touristic business with revenue in 2010 of 8.3 million euros, which reached 21 million in 2019.24 This is no surprise when we consider that the localities of archaeological and cultural interest registered about forty-three million incoming visitors in 2018, more than half of them foreigners. Culture indeed represents the first motivation for traveling to Italy, Rome being the favorite destination for cultural tourism with twenty-seven million visitors each year, both Italian residents and foreigners. The most visited heritage sites in Italy are, however, only three sites: two archaeological complexes—the “Colosseum–Roman Forum–Palatine Hill” in Rome and the archaeological site of Pompeii—and the Museum “Galleria degli Uffizi and Corridoio Vasariano” in the historic center of Florence, which hosts one of the most impressive collections of Renaissance art worldwide. These three complexes are among the forty-nine cultural heritage sites inscribed in the World Heritage List,25 and alone they host 26 percent of the total of visitors and represent 52 percent of the total revenue from cultural tourism in Italy.

Besides the controversy of considering archaeological sites and culture valuable when it produces an income, these data show also that the measures that Italy needs to implement for the safeguarding of these three World Heritage sites need to be exceptional, as these delicate structures support a massive number of visitors.

The case of Pompeii is emblematic. In 2018 the site registered the impressive number of 3.6 million visits, with more than 450,000 of them concentrated in July. That means that during summer the site needs to bear about 20,000 visitors per day.

A large number of these visitors are cruise tourists, who disembark at the port of Naples and reach Pompeii mostly by bus. The common characteristic of the visits of cruise tourism is a very tight schedule, and for this reason the guides accompanying them through Pompeii choose two specific itineraries, passing through some of the site’s highlights and comprising less than thirty points, which are visited in about three hours. The Forum represents the core of the visit, and it is perceived as the heart and the symbol of the ancient city together with the Lupanare (brothel), which inspires curiosity in the visitors because of the topic of sexuality in the ancient world and for the presence of frescoes with erotic themes. The other monuments that are highlights of the visit are the Teatro Piccolo, the Pompeii Odeion, and the Quadriportico dei Teatri or Caserma dei gladiatori, which present to the visitors other interesting and iconic aspects of ancient life, the theatrical performances and the gladiator’s fights. In total, the statistics show that the most visited points of interests in Pompeii are not more than eleven, as the overwhelming part of the guided tours are short and logistically connected to two of the points of access and exit of the site.

The mapping of the most common touristic itineraries and visit flows in Pompeii show that the regular tours concentrate visitors only in a very small portion of the site.26 Studies have shown that the warming caused by this massive human presence in Pompeii is harming old structures by enhancing the humidity levels of the site and altering the chemical composition of the air. Furthermore, the passage of such huge numbers of people is causing severe damage to surfaces, paintings, and mosaics. Together with other factors, such as accidental and voluntary damage of the heritage, these issues are posing a great challenge to the conservation of the site. There are several projects that aim to restructure Pompeii’s itineraries, but the threats to the site caused by overcrowding represent still one of the major issues in the delicate balance between the development of tourism and the preservation of the archaeological sites.